Table of Contents

I. Introduction |

4 |

II. Constitution and Legal Transitions |

6 |

1. Total Constitutional Transition |

7 |

2. Partial Constitutional Transition |

9 |

III. Dynamic Explanatory Model of Legal Transitions |

10 |

IV. The Transformation of a Constitution |

13 |

1. The Structure of a Contemporary Constitution |

14 |

2. Constitutional Models |

16 |

3. Institutional Design |

18 |

V. Conclusions |

20 |

I. Introduction

Since the transitional context has been largely discussed from a political perspective, the transformation of a constitution in ordinary and transitional times will be discussed here only from the point of view of legal theory. Constitutional design has been governed by the universalistic liberal ideal; the transformation of a legal system is, therefore, usually led by the rule of law, which plays a definitive role in a legal system’s change focusing on legal certainty. The rule of law is a standard of constitutionality even if it is only considered a formal principle. The starting point for the explanation of legal systems and their transformation in Western models of constitutionality is to consider the constitution as the supreme source of law.

The debate has revolved around the rule of law without discussing its meaning but rather starting from idealized models assumed to be generally understood in the same way.2 Nevertheless, the rule of law as an ideal developed historically in the European legal tradition, is understood as a combination of statutory regulation and judicial decisions to keep law and order, to control the government according to the principle of separation of powers, and to provide for the protection of individual rights and a certain degree of democracy.3

A constitutional transition implies a profound transformation of a legal system, and it can be analyzed by considering the procedures used to modify a constitution or its contents. Given the complexity of constitutional dynamics, it is relevant to distinguish the creation of a constitution from its revision. I will focus here on the general aspects from a material perspective. Without trying to suggest specific contents, which the modern constitutionalism has examined sufficiently,4 the idea is to propose a model that could be helpful to explain constitutional dynamics and the process of transformation of a legal system. For that purpose, the basic contents of a constitution could be used as guidelines to assess the degree of change.

For some countries, the discussion about a transition is related to constitutional amendments, especially after multiple and constant reforms made to said constitutions; for others, it arises from the process of enacting a constitution or substituting a constitution that is still in force. Two different meanings of constitutional transition are then to be discussed: ordinary and extraordinary transformations.

In order to speak of constitutional transitions -here considered as a specific form of legal transitions, since the study will be conducted from an analytical perspective some of the most significant concepts for this matter, such as constitution and legal system will be revisited. The purpose is not to define these concepts, but to build an explanatory model of constitutional transitions, so only a general delimitation will suffice. It is important to remember that the object of this article is to explain legal transitions, not political or democratic transitions. I will only focus on the role of law in the constitutional transformation of a legal system. Since the constitution is considered here as the first legal rule of a legal system, the analysis revolves exclusively around profound transformations of a constitution.

Understanding the legal system and the structure of the constitution as well as their operational rules, is a methodological requirement to explain the scope and limits of a legal transformation. A specific concept of the legal system, as a dynamic system, is considered necessary to explain the different forms of transformation of the legal system; that is, ordinary modifications that produce gradual transitions, as well as replacing a constitution. An appropriate analysis of a legal system requires its understanding as an individual coherent set of interrelated rules for identifying constitutional transitions.

Due to the founding nature of constitutions, it is important to study legal transitions according to the dynamic theory of law. As Kelsen held, it is a unique property of the law that it governs its creation.5 The dynamics of the system is law’s regulating principle that guides the identification of constitutional transitions. Since the constitution regulates the rule creation process, it is logically superior to the other rules of the system, which implies a hierarchical structure, and to understand it as the supreme norm of a legal system. Law as a system is a system of rules, and legal rules interrelate because they form a whole according to a specific criterion, which from the perspective of legal systems can only be another legal rule that regulates its transformation.

II. Constitution and Legal Transitions

Legal transitions must be explained starting from the constitution, not only as a result of its foundational function as the first legal rule of a legal system, but also due to its normative nature. The question of the validity of the first rule is placed apart since the transition from one legal system to another by virtue of the creation of the first constitution of a legal system will not be addressed here.6 The existence of power-conferring norms to amend a constitution or frame one is of paramount importance for transitions to be characterized as legal procedures. Otherwise, the result cannot be properly called a legal transition.

The concept of “legal transition” implies that the modification of the legal system happens by legal means. Yet, formal procedures will not be analyzed because the transition is explained here as a process of material transformation of a legal system. When a constitution is substituted by a revolutionary act, it cannot then be called a constitutional transition from a legal point of view.7 In the classical view, revolutionary political change may result in constitutional change as an extra-legal modification of the fundamental principles of the existing constitutional order; illegality is inherent to a revolution.8 Therein lies the conceptual dilemma of considering the process to enact a constitution after a revolution as a legal transition strictly speaking.

However, constitution-making does not need to be the result of a revolution, even if it is usually the consequence of profound political change. It is an act of foundation given within a certain political and legal framework and could be the outcome of negotiations or a pact somehow upheld in the previous legal order. Higher lawmaking should be though a process conditioned by heightened, deliberative decision-making because it is done with the intention to create a new political entity.

Traditionally, a constitution has been considered as a State’s fundamental political arrangement, inasmuch as it lays out its organization. Nowadays, it is also considered the most important rule of a legal system and its constitutive function is warranted by the control mechanisms it regulates. It is a binding rule, directly valid and its content forms the basis for decisions of a constitutional court.

According to Kelsen, a constitution represents the highest level of positive law. Its main function “consists in governing the organs and the process of general law creation”, and it “may determine the content of future statutes”.9 In Hart’s terms, a constitution has provisions considered as primary rules, i.e., fundamental rights, and secondary rules such as power-conferring rules and procedural rules.10

The term “transition” means to change from one form to another, or the process by which it happens,11 but it can also refer to a period of changing from one state or condition to another.12 So, legal transitions regarded from a constitutional perspective can be distinguished by their “transformative” effect, and we can speak of total or partial transitions. A “total transition” occurs when a legal system is substituted by another when a new constitution is enacted, as would be the case of the German Constitution of 1949, for example. “Partial transitions” happen when relevant legal institutions are included or transformed in such a manner that the original model13 is modified or substituted within a constitution. The Constitution of the United States, e.g., underwent a partial transition process with the inclusion of civil rights and liberties. To distinguish the procedures and given their effects, the first can be considered a legal system transition, and the second a constitutional transition stricto sensu, even if constitutional provisions are involved in both cases.

1. Total Constitutional Transition

Total transitions can result from different events: revolutions, ruptures or reforms. This kind of legal transition is instantaneous. In this sense, transition means a change from one legal system to another as a consequence of replacing the constitution. The enforceability of the new constitution is essential to consolidate a total transition.

A total transition may be due to a major reform in relation to the change in the form of state or government, with which the people and the governing bodies are satisfied, or mostly agree. These processes can rarely be called legal in the strict sense of the word because the legal basis for such a change of the constitution cannot be a provision established by the previous system that the new constitution is overturning, and negotiation generally takes place on a political level.14 But a change of system is not necessarily the result of a revolution or formally illegal. It may so happen that the change of system occurs through reforms provided for in legal documents issued by competent authorities. And when these legal reforms result in a new constitution, they produce a change of legal system.

However, this is not the usual process in the case of a change of legal system. On the contrary, this generally happens through violence undermining the established legal system and through behaviors the system classifies as criminal. The legal effects are the abrogation of the constitution in force and the creation of a new legal system. When a new constitution is enacted, the previous constitution thus loses its validity, and a legal system transition takes place.

The political effects are the change of regime, the modification of the established order, the substitution of the government and the conformation of a new social order. Ruptures are mostly caused by claims related to a needed transformation of the regulation and operation of any of the fundamental elements of a constitution.15 A total transition is a system rupture manifested by replacing the constitution. The new contents generally reflect a change in the conformation of the State, but especially in the form of the government’s integration. A transformation can be then perceived when important parts of the subject matter of the constitution are modified based on a specific model.

By enacting a new constitution, a new legal system emerges. Yet, the rules of the previous system (pre-constitutional rules) that do not contravene the new constitution may still be considered applicable and integrated into the new system. This option depends on the provisions of the new constitution and the decisions made by the law-applying organs regarding their compatibility. But those that contravene the constitution will lose their validity due to their newly acquired unconstitutionality. It can be said that after a total transition, the new legal system operates at first by “importing” all legal material than can still be called valid according to the provisions of the new constitution. This was the case in Mexico, for example, after the revisions made were enacted as the new Constitution of 1917.

Legal systems can admit partial constitutional continuity for law originating in a previous constitution and so confer validity to pre-constitutional law by resorting to the principle of coherence. The validity of those rules is more a question of compatibility of the previous rules with the new constitution than an issue of the moment when they were issued. It can thus be said that the rules in effect on the day a new constitution enters into force may be deemed valid if they are consistent with the new order.

2. Partial Constitutional Transition

In relation to changes within a legal system, the constitutional reform procedure allows ad intra transitions while maintaining social peace and order. An internal constitutional transformation can be considered as evolution, and several stages can be identified by analyzing the relevant revisions made. Legal transition, in this sense, is a process, a construction that implies a decision to issue new laws or carry out radical reforms to the constitution.

Due to the dynamic nature of law and as the object that it regulates is human behaviour, the power to modify the constitution is indispensable. The extent of a revision may produce a partial and gradual internal constitutional transition. This kind of transition reflects a need to adapt the constitution so that it preserves the continuity of the legal system. So, a transformation that occurs within the constitution is here considered a partial constitutional transition.

Constitutional transitions can then occur slowly, by amending different legal institutions and preserving legal continuity. An example of a smooth constitutional transition is the amendments to the Constitution of the United States regarding individual rights. When done step by step, it can be considered as legal development, and this can be “channeled through patternborrowing and transplants”.16 The substantial elements of continuity can be identified by reference to the basic structure of a contemporary constitution, which are key elements of the doctrine adopted by the dominant model in the constitution. This structure is discussed below in section IV, 1. The organization of State power as a system of the highest State bodies is a typical element of continuity and since legal traditions are formed in the process, they are also indicative of it. Constitutional change can be evaluated according to the criteria of model, institutional design and institution provided in sections IV, 2 and 3.

It could be difficult to admit a profound transformation of the constitution that might seem “revolutionary” -in a figurative sense- as legal transition. It would also lead us to reflect upon its identity and even question whether it is formally the same constitution. A constitution is in constant transformation through the interpretation of the competent courts and the revisions made.

A balance between the modification and the application of a constitution is thus necessary to preserve its normative force.17 A subtle transformation considered evolution of the legal system is also possible by means of its application and interpretation, but it could not be considered a transition because a profound transformation of the constitution is only possible by means of constitutional revisions even if their implementation also has an important impact on the changes of the meaning of its legal institutions.

Constitutional amendments are modifications that do not formally imply the substitution of a constitution, despite the degree of change made. According to a rule of law model, there must be coherence between the actual text and the revisions made to the constitution and intended to reinforce individual liberties and to guarantee the exercise of fundamental rights.

III. Dynamic Explanatory Model of Legal Transitions

Due to the dynamic nature of law, an adequate explanation of legal transitions, requires, in my opinion, a differentiation between the concepts of legal system and legal order,18 as in the case of Raz,19 who distinguishes the concept of legal system from that of momentary legal system to differentiate them, or Alchourrón and Bulygin who have already suggested this for other purposes.20

This methodological consideration is important for constitutional transitions, especially to analyze transformations within a legal system to then separate periods of time distinguished by a dominant model. With total constitutional transitions, it becomes important to ascertain when a constitution is “legally” replaced and when a new constitution does not acquire sufficient legitimation or efficacy and the former constitution recovers its full normativity.21

The analysis of these two types of constitutional transitions can be better understood from a systematic perspective by differentiating a legal system from its momentary legal orders. A total constitutional transition can be recognized by a new legal system marked by a new constitution that guides the adaptation process, as the new system is accepted and becomes efficacious and the previous one loses its validity -what I call the inter-system period. And a partial or internal transition can be determined by following the development of the constitution after a new model is inserted or modified by some specific institutional design, from the moment certain legal institutions enter in force until their derogation. Both processes of change point towards a certain form of transition that will alter the operation of the legal system.

The method regarding the second type requires us to distinguish different legal orders in time centering on an institution considered significant for qualifying a constitutional change as a transitional process. In this way, an internal legal transition can be studied by comparing different yet characteristic institutions to a specific model. The interval between the two moments during which some institutions are added or modified to introduce a new model or to adapt it can be called a transition.

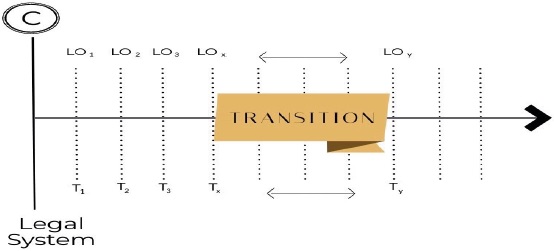

The difference between legal system and legal order can be explained by the way the rules function over time, since the operation of the rules that belong to the system is diachronic, and that of the rules of the legal orders is synchronic. To distinguish one legal order from another thus make it possible to specify a moment to determine the rules in force at that specific moment. The legal system could therefore be represented as a horizontal line, starting with the constitution and, ending only when a new constitution substitutes it.

All the rules issued according to the prescriptions of a legal system belong to it, even if their validity is only prima facie.22 In addition to the provisions in force at the time of making a decision, the repealed rules are considered part of the system so as to preserve legal certainty and the validity of the acts and legal effects already produced. The assumption is that the function of derogation is not to eliminate legal provisions, but to prevent them from producing new effects in the future because they will not be in force anymore. In legal practice, derogated rules can be applied exceptionally by means of transitory legislative provisions to that end, or based on diverse principles regarding legal certainty, especially in criminal law, for example.

Following Alchourrón and Bulygin, a dynamic system of norms can be described as an infinite succession of legal orders, which differ from each other by the set of norms comprised in each one. 23 So, a legal system is therefore a sequence of sets of norms. It should be pointed out, that a legal order, regarded as a set of rules, is equivalent to the system only when the Constitution enters into force. By introducing a general rule, this coincidence ceases and gives way to the successive legal orders that form the system. The criterion to identify the rules is their membership to the system, which is not affected by the modification of their validity or effectiveness. This understanding of the legal system helps explain different legal phenomena, such as the retroactivity and ultra-activity of the rules because it allows to move in time to determine the applicable norm to a specific case.

As mentioned above, a legal order is synchronic. It identifies a set of rules that are applied simultaneously. This can be represented by a vertical diagram that provides legal certainty by determining the rules that can be applied at a specific moment. A legal order is then understood as a set of rules applicable at a certain moment to one or many specific cases. This is a static representation since changing a single general rule results in a different set of rules and the change from one legal order to another.

Every time the legal system is modified either by the creation or derogation of a general rule, the current legal order is replaced by another one because the set of rules has changed. Derogation causes a change of legal order and thus derogated rules do not form part of the new one. Regarding constitutional transitions, the possibility to distinguish legal orders from the legal system helps to determine the moment when a transformation starts or the duration of a certain model. This kind of transition requires time, so a period of change must be selected to evaluate the degree of the modification based on its effects.

Each legal order shares with the previous orders most of its rules, and all of these depend on the constitution, which determines their meaning and the relations between rules. Due to its function, the position of the constitution in this representation is at the beginning of the legal system for it constitutes the system as a whole, as well as above the rules of each legal order at a given moment.

A partial legal transition is identified by studying the revisions made in a certain time frame, analyzing the interval between LOx and LOy for example.

IV. The transformation of a Constitution

The notion of system implies its development according to an axiom or set of axioms. In this case a legal system arises from a rule, the constitution, mainly because its validity is not legally questionable.24 All the rules of the legal system derive from this first rule, not in a logical, but in a legal sense according to the provisions of the fundamental norm. Following Kelsen’s theory, the validity of the norms of a legal system depends on the possibility of tracing its legal norms to the constitution.25

Since the constitution itself operates as a system, to understand it as a unity allows for its systematic interpretation, which can produce modifications of the institutions it regulates as a consequence of the process known in constitutional legal science as “mutation”.26 In German doctrine, “mutation” is the possibility of altering the meaning of a provision without modifying the linguistic sentence that expresses it; the legal sentences are preserved, but are given a different meaning.27 Despite not being modified by the regulated process, the constitutional provision acquires new meaning. In a way, we can think that a form of mutation also happens by means of amendments that result in legal transitions.

Identifying a transformation in a legal system that could be called a partial constitutional transition (or internal transition) requires examining specific amendments or the sum of reforms made during a certain period. The explanation and analysis of the contents of a constitution requires the study of its institutions, identifying their institutional design and the form in which they correlate. Therefore, it is important to understand the structure of the constitution since the meaning and operation of legal institutions depends on the models operating within the constitutional frame; I shall proceed to explain these concepts in the following sections. Any change in a constitution, but especially in the model and the institutional designs, produces a change in the interpretation and application of subsequent legal orders.

1. The Structure of a Contemporary Constitution

Because legal rules form a system, they do not operate in isolation and their meaning depends on the way they relate to each other. Some constitutional provisions are operative in the form of legal institutions -such as due process, rule of law or separation of powers. This implies that many legal provisions are connected to each other in a special way. One could say that an institution is a group of rights and obligations operating together in unity.

Every constitution is drafted according to certain ideals or following some kind of model. Contemporary constitutions envisage one or multiple models that are modified over time by various institutional designs that transform the meaning of some of the legal institutions regulated in the fundamental norm and these designs can be used to produce a modification of the model itself.

Based on article 16 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789,28 modern Constitutions, that is, those following the rule of law tradition, share a common constitutional structure. It is generally accepted by constitutional theory that this basic constitutional structure must include fundamental rights and the separation of powers. These mandatory contents are the elements that identify a rule as a constitution. Most western contemporary constitutions share this common constitutional structure and State power, as regulated in a constitution, is usually exercised by three types of bodies: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.29 Any modification of the balance of powers assigned to these organs can be indicative of a partial constitutional transition, for example: amendments to increase the powers of the executive branch could indicate a transition to a more presidential form of government while the creation of constitutional autonomous bodies in charge of specific functions could point towards a more decentralized model.

Ever since the constitution began to be considered a legal norm instead of a political document -one could say that the decision in Marbury v. Madison was the turning point in this matter, judicial review becomes the third fundamental pillar in the structure of the supreme norm. In this way, a balance between fundamental rights and the separation of powers is legally warranted. The possibility of a judicial control of the constitutionality is at the core of the effectiveness of the constitution since it ensures its normative force. The purpose of this form of control is to safeguard constitutional supremacy by subordinating legislators and the law to the constitution.

These three pillars form the constitutional structure, but given the complexity of contemporary constitutions it is important to also consider three other elements in order to have a complete picture of the constitution and its operation. The supplements to this constitutional structure are the sources of law, the democratic or participatory procedures and the regulation of the economy, all of which provide a better understanding of the nature and function of a constitution.

As the foundational rule of a legal system, a constitution regulates the sources of law, which are directly related to the control of constitutionality. Competence norms and judicial review are key to explaining the dynamics of law because of their role in the creation and modification of a legal system. The proliferation of sources can be indicative of a transition in a legal system because it shows unbalance in the separation of powers perceptible in the regulatory powers of the Public Administration, for example.

Since the regulation of democracy has become an important aspect of the constitution, provisions on participation in decision-making processes must be considered in the evaluation of a constitutional transition and in relation to the constitutional design of the principle of separation of powers. A democratic transition for example can be explained according to a given theoretical framework, looking for modifications in some institutions made in a specific way. This is also so in the design of a specific kind of democracy, deliberative or participative, for example.30

The third complementary element to consider in the evaluation of a constitutional transition is the role of the State in economic relations in terms of the economic model adopted in the constitution, which is closely related to many fundamental rights.31 All these structural elements are correlated and ultimately overseen by means of constitutional controls.

The analysis of constitutional transitions must consider first the three pillars of the constitutional structure, that is, the fundamental rights, the separation of powers and the judicial review of the constitutionality of legal rules, but also the economic model, methods for participation in decision-making processes and sources of law. Constitutional transitions can so be evaluated according to these fundamental criteria, so much so, that they can be considered content references of a legal system that operates according to a certain model.

2. Constitutional Models

Within a constitutional structure, legal institutions operate according to a model which is determined by the relation established in the constitution between each of the above-mentioned elements of the constitutional structure. Regarding the process of constitution-making, the concept of model can be understood as the representation of a certain form of political organization of society recognizable by the way in which distinctive institutions are regulated in its constitution.

When a certain model, be it liberal, social, or democratic, for example, is introduced in a constitution, it sets a goal to be achieved and portrays the kind of society desired. The criteria that outline a model could be the main functions of the State, the guarantee of fundamental rights or specific values, for example. These ideas would act as rules for the interpretation of the constitutional provisions.

The model can be identified by the prevalence of one or other pillar of the constitutional structure and a tendency towards one extreme. The balance between each one of the structural elements goes beyond the mere distribution of power among constitutional bodies -checks and balances-. It also implies, at least, providing for their accountability, the protection of fundamental rights and a warranted constitutional control.

Each model delimitates the legal institutions that can be included in the constitution. There may be more than one model in operation in a constitution, but there is usually a predominant model that determines the general nature and operation of the constitution. Constitutional models can be identified according to certain principles, values, or goals, or by selecting a group of institutions that are recognizable as a whole upholding some common justification or object. The models can interact with each other, and a new model does not necessarily replace a pre-existing one. The degree of how effectively they work together will depend on the extent to which they complement each other.

Models are created following interests deemed relevant at a specific historical moment and answer therefore to historical circumstances and social expectations. The decision to introduce a new model is usually a response to a serious claim that requires immediate attention. The object is to produce a profound transformation of behavioral patterns or to change the form of government, for example.

Whether there is an intent for a genuine transition with a change of model -especially regarding governments fond of reforms- is not always clear. The transformation of the current model cannot be determined a priori because the degree of change of a legal system is only perceived over time. The model is sometimes copied from other legal systems, sometimes instrumentalized. A legal system transition is often carried out by importing a model or receiving legal institutions considered important. International Law and globalization have had an influence in legal transitions that is noticeable in constant legal transfers and the importing of legal institutions in many constitutions. For a constitutional transition, coherence regarding legal institutions brought from foreign models is of the utmost importance; otherwise, they end up being dysfunctional.

So, within the frame of the pillars that form its structure, a constitution contains a model that must be carried out. This model establishes the guidelines regulating the State’s and society’s action. Every new constitution contains a foundational model, which over time can be modified in different degrees to answer to a country’s new needs and expectations. As consequence of current social and political dynamics -whether national or international- other models can later be introduced into the constitution.

Models can coexist even when they seem conceptually contradictory. The introduction of a new model produces a sort of “mutation” to the meaning of the institutions.32 As already mentioned, a new model does not necessarily reject or substitute a previous one; they can function together. They are ordinarily inserted within the constitutional structure successively, and usually interact together. Each model has diverse representative institutions that can be created and modified according to a certain design.

The models are not rigid. Their meaning can change according to the modification or introduction of certain institutional designs to adapt particular legal institutions in a specific way to achieve an object, as well as through court decisions. The designs are rational mechanisms created to provide legal coherence to the existing models. They are answers or reactions to the operative deficiencies of regulated legal institutions to preserve the coherence of a constitution as a whole.

For that purpose, the interpretation of constitutional amendments, especially when new designs are added, is guided by the principle of non-contradiction to eliminate situations that seem to produce contradictions between constitutional provisions. So, when legal sentences allow it, the principle of coherence sees to the compatibility of institutions to preserve the unity of the constitution. If an instance of incompatibility cannot be overcome by interpretation, the legal means to solve it would have to be provided for in the constitution. This could be a case of the so-called “unconstitutional amendments”, but that is another issue. The scope and limits of the ability to interpret the amendments must be adequately regulated to avoid problems due to excesses committed by constitutional courts that can produce transformations in a legal system beyond mutations through interpretations considered acceptable.

The dynamic of the constitution presupposes the existence of a foundational model that establishes the meaning of the institutions regulated by the constitution. In time, the model can either consolidate or require modifications to stabilize it. There are also periods of normalization or review of the model. Historical constitutions with a long life can also experience a process of modernization. “Transition” is perhaps an adequate term to speak of the transformation of a constitutional model as it describes the uncertainty regarding the predominant model and its characteristics.33 When the drafting of the constitutional model is not premeditated, the new type of model that emerges from the reforms will remain unknown until its effective operation can be evaluated.

From a scientific standpoint and for the purpose of analyzing constitutional transitions, models could be thought of as “ideal types”34 because they do not describe the real world. A model is a mental construct considered desirable and often originally a theoretical product.35 Reforms to a constitution can be evaluated according to certain properties attributed to a specific model, such as the regulation of property or civil rights and liberties in the liberal model. The assessment of a constitutional transition and its degree of transformation is done retrospectively since it can only be evaluated ex post by its effects or success in achieving its objective.

3. Institutional Design

Based on the preliminary notions given, the institutional design is understood here as a group of provisions that are related by a specific criterion, enacted to improve the efficiency of regulated legal “institutions” by modifying the rights or obligations established according to a certain model. The design thus serves to imprint a specific meaning on some legal institutions to fulfill a certain foreseen objective that should be identifiable through the justification of the proposed constitutional revision.

“Institutional design” is a tool aimed at correcting a model and is used for its interpretation and redefinition as it changes the meaning of legal institutions. Its function is to make the institutions compatible, since their meaning has been altered with the introduction and possibly the superposition of different models in a historical constitution. These designs are often created to respond to a situation or offer short-term solutions that should satisfy certain political and social needs within a determined lapse of time.

The design can be identified as a package of constitutional reforms carried out simultaneously or within a relatively short period of time, based on certain criteria that give them a sense of connectedness. Sometimes, when the institutions prove to operate together, the institutional design can be formally identified by the enactments of the reform of various constitutional articles justified in a common end or value.

Institutional design determines the operation and interpretation of institutions because it establishes the way they interact to produce a specific result. The design is made evident by the selection of the institutions connected by the same purpose. A partial transition can be perceived in the incorporation and implementation of an institutional design regarding the form of government, for example.

There are two types of institutional design. Distinguished by their objective, there is a “constructive design” that aims at creating a new reality or form of interaction between the government and the governed. The second type is “justificatory” because it has a legitimating effect on a changing reality. The first one is, so to say, an intellectual creation instrumented to change the reality through regulation by combining some institutions according to a planned design in which the costs and benefits of including said new design in the constitution, as well as its implementation, have been calculated.

In the case of the justificatory design, its object is not only to legitimate and legalize an actual way of behaving, but also to correct unwanted or negative effects of non-regulated uses and practices that have a certain degree of acceptance. When the latter are considered convenient, they can be construed as institutions by adapting them to the legal system in such a way that they can acquire legal force and act as limits and obligations to authorities. This kind of design is frequently used when reality surpasses the lawmakers because of great advances in technology or the increasing speed of the dynamics of international relations, especially in trade matters, for example.

The institutional design assumes a consideration on the suitability of including some institutions in the system or whether their operation and meaning should be modified. The analysis of their compatibility with other institutions in the system and the calculation of possible side effects must also be made. Even if it is true that because of the complexity of law all the alternatives of possible interpretations of a rule in a legal system cannot be determined a priori, when the project is developed, besides the historical reasons and the opportunity of the reform, the coherence and independence of the institutional design must be taken into account. Legal practice is another important factor to be considered when determining the meaning and application of an institutional design.

V. Conclusions

To speak of transitions from the point of view of legal theory, it is important to understand the structure of the constitution, since the meaning and operation of its institutions depend on the predominant model within its construction. The analysis of legal institutions is key to the identification of legal transitions to determine the evolution of a legal system and help distinguish a new model.

An adequate application of constitutional rules requires that the structure of a constitution, as well as the model that the framers of the constitution intended to establish with the regulation, be considered. The elements of the constitutional structure are of paramount importance to interpret the constitutional amendments so as to determine whether a constitutional transition has taken place.

Some institutions are hallmarks of specific constitutional models and the change of those institutions, or their design, may have a profound impact on the meaning of many constitutional rules. Any change in the constitution, but especially the modification of institutional designs, produces a change in the interpretation and application of its provisions.

The adaptation of the models is first instrumentalized by courts decisions and the public administration. The implementation of public policies are other indicators of the model prevailing in a constitution. It is up to the judges and the administrative authority that apply legal rules, to determine which institutions define the model. The balance between the exercise of the State’s functions and the administration of justice provides for the rationality in lawmaking and application of the law. The last word on the meaning of a model corresponds nevertheless to constitutional courts.36

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)