I. Introduction

Defining distributive justice is not an easy issue. In fact, if someone wants to write about it, it is very important to establish first what will be understood by it, which author or school of thought will be followed, etc., in order to make clear to the reader what the writer means by this concept. According to Samuel Fleischacker1 distributive justice has been understood in two senses throughout the history of the tradition of political philosophy based on ancient Greek thought: the Aristotelian and the modern sense. In general terms, the first one refers to giving everyone what they deserve according to their merits and the telos or purpose of the thing to be allocated,2 while the second one, the object of this research article and also called “social justice” today,3 refers to a duty of the State to guarantee everyone in society a certain level of means to satisfy their needs.4

On November 26, 2007, the United Nations (UN) established World Social Justice Day, to be celebrated on February 20 each year.5 By doing so, the UN placed social justice as one of the most important issues that it has to promote in order to achieve its original purpose of preserving peace and security in the world. Certainly, social justice is an omnipresent and controversial issue both in politics and the law today. In politics, for example, the highest chief of FARC-EP guerrilla, Rodrigo Londoño, alias Timochenko, after hearing of President Juan Manuel Santos’ nomination to the Peace Nobel Prize, said that the only prize his guerrilla wanted was peace with social justice.6 Now, in the legal arena, there are nearly seventy constitutions around the world that enshrine the expression “social justice” -despite the different cultures and backgrounds- as a purpose or principle of the State itself.7

In Colombia, even though the Political Constitution of 1991 doesn’t explicitly enshrine the expressions “social justice” or “distributive Justice” as a purpose or principle of the State, it should be stressed that the Constitutional Court, its main and ultimate interpreter and a world-renowned institution because of its active protection of social rights in the last two decades, has applied those expressions in its judgments since its foundation in 1992. Actually, in a very famous judgment in 1992, the Court mentions social or distributive justice as a matter of allocation of means with the aim of guaranteeing social rights in the new Social Rule of Law.8 Nevertheless, the judgment also includes a corrective function in the sense that distributive justice also allocates punishments, which, as will be explained later below, is against the principles of Social Rule of Law and human dignity, and the right to material equality, enshrined by the Constitution.9

It is important to point out not so much why the Court has applied an old-fashioned and unconstitutional notion of distributive justice,10 but that, even though there is no mandatory rule in the Constitution that enshrines social or distributive justice as a purpose or principle of the state, the Court has continuously described it as a purpose of the state itself in its judgments since 1992.11 At least three questions arise from this fact: Is it permissible for a Court, the Congress or the executive to appeal to an extra-systemic purpose or principle when drafting, for example, a judgment, an act, a decree, etc.? Is social justice just an expression that Colombian legal practitioners, judges, and legal scholars should not take into account? And, can it be freely interpreted and applied both in the Aristotelian and a modern sense without contradicting the Constitution?

In this article, i will try to support the argument that, even though it is not a purpose or principle enshrined by the Constitution, the modern notion of distributive justice or “social justice,”12 and not the ancient one, is an implicit idea in the Constitution, because the latter enshrined the three main elements of such a modern notion, i.e., the principles of Social Rule of Law and human dignity, and the right to material equality, which were available in the global constitutional discourse of the years in which the Constitution was promulgated.13 So, the expressions “social justice” or “distributive justice” can be used in the national constitutional discourse,14 but by following the principles and the right above, i.e., it ought to be understood, at least, as a duty of the state to guarantee a certain minimum means, based on human dignity and a different treatment in benefit of the poorest, discriminated, vulnerable, and marginalized people in society. Finally, the proposed meaning can be proved by the fact that, if the ancient or Aristotelian interpretation of distributive or social justice is followed in the constitutional discourse, e.g., in a judgment, it would disregard, even violate, the two principles and the right mentioned above.

So, the general objective of this article is to demonstrate that, even though there is no purpose or principle of social justice in the Colombian Constitution of 1991, social justice is implicit in it and can be achieved by guaranteeing the principles of Social Rule of Law and human dignity, and the right to material equality. The first specific purpose -although without exhaustive pretensions- is to contribute to clarify the meaning of the expression “social justice” today in the global constitutional discourse, by presenting new evidence about its origin, historical evolution, and relation with the principles of Social Rule of Law and human dignity, and the right to material equality, which are, in fact, the three legal tools of the State to materialize social justice. The second purpose is to show that, by enshrining the two principles and the right mentioned above, social justice has become implicit in the Constitution of 1991 and can be used in the Colombian constitutional discourse if it is only understood according to those rules and not to the Aristotelian sense of distributive justice. Finally, the third specific objective is to prove that the achievement of social justice in the Colombian State is possible and requires, essentially, the fulfillment of the principles of Social Rule of Law and human dignity, and the right to material equality, which are mandatory rules to the branches of power and the civil society. So, the justification for this research article is evident, because the clarification of that expression can guide the agents of the legal field, mainly in Colombia, but also in the world, on how to understand social justice in order to have the tools to materialize it through Law.15

Now, in the first part, by following the methodology proposed by the Socio-cultural and Transnational School of Legal History, which states that a legal institution (e.g., the Social Rule of Law, human dignity, material equality, distributive justice or social justice, etc.) should be contextualized according to “its preconditions and effects on a concrete society and culture, under a transnational and comparative view,”16 an attempt will be made to construct a historical overview of the evolution of the modern notion of distributive or social justice in the comparative constitutional discourse. In the second part it will be shown: i) that the main elements of the modern notion of distributive or social justice presented above were enshrined by the current Colombian Constitution in 1991, ii) how a Colombian constitutional meaning of social justice would be like, iii) how the application of an Aristotelian meaning of distributive or social justice in the constitutional discourse would disregard and even violate mandatory principles and rights, and iv) some examples on how distributive or social justice can be achieved by applying such a meaning in the national constitutional discourse. Finally, as a summary of the two parts and a reflection, a brief conclusion will be drawn.

II. A Short History of Social Justice in Global Constitutional Discourse

1. Aristotelian Distributive Justice

In his book Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle distinguished between two notions of justice: the first one called “universal justice,” which includes all the virtues, and a second one called “particular justice,” which belongs to the world of politics and judicial decisions. Within the latter notion, Aristotle presents two subtypes: corrective justice and distributive justice.17 The first one refers to the elimination of the benefits and losses produced by a situation of inequality in voluntary or involuntary interactions, in order to restore equality between the parties of these interactions. This type of justice was more commonly known as commutative justice, a name that derived from the Latin expression used by Thomas Aquinas justitia commutativa in which commutare means “to exchange”,18 and whose use can be noticed in the judgment that is discussed here. The second type of particular justice says that political offices and property must be awarded according to merit; here, Aristotle points out: “all men agree that what is fair in distribution must be according to merit in some sense.”19 However, the understanding of this distinction has not been peaceful throughout the centuries and has been permeated by the context from which Aristotle has been read.20

Thus, equality in corrective justice imposes a rectification of the inequality caused within a voluntary or involuntary interaction, regardless of merit, for example: when a judge sentences someone to pay a prison sentence for homicide, he does not consider whether the condemned man deserves the punishment because he was a bad man, or if he does not deserve it because, in spite of everything, he was a good man. Therefore, Aristotle clarifies that “it makes no difference whether a good man has defrauded a bad man or a bad man a good man ...the law looks only to the distinctive character of the injury.”21

In distributive justice, equality is achieved through the sharing of common assets (e.g, property or political positions) available in a society ruled by the same constitution, according to the merit of the person to whom such assets will be awarded. Justice requires that those assets be proportional to the merit of the individual to whom they are to be awarded. For this reason, it is unfair to treat the “unequal in merit” as “equal in merit,” giving them equal assets.22

If merit is the basis for doing such a distribution, then: what is merit? Aristotle does not give a definition of merit. In fact, he notes that people may disagree on the meaning of merit in distributive justice and does not take sides in the debate expressly.23 Nevertheless, it can be said that, in general, merit constitutes a measure of the accomplishment of certain requirements that make a person be a part in distributive justice.24

Aristotle argues that the concept of merit depends on the type of political regime that a community has. Thus, in an oligarchy, wealthy or noble birth are the basis to make the distribution of the benefits: whoever had more wealth and a better rank deserved to receive a better public office than the one that did not have them at all; in an aristocracy, aristocrats would insist on a distribution according to excellence; finally, in a democracy, they would say that distribution should be based on freedom, that is, a free citizen would have certain benefits that a slave would not have.25

According to Aristotle, once the meaning of merit has been given, it will be possible to allocate the benefits in a political community, a distribution that will take into account the relevant merit to the thing to be allocated.26 For Aristotle, if there is a flute to be allocated, it should not be given to those who were born in a wealthy or noble family, but to the person who can better play the flute, because that is the person who can better fulfill the purpose for which the flute was designed, i.e., being well played to produce the best music.27

In this way, a reasonable answer to the question about the meaning of merit for Aristotle is that it is the virtue or excellence relevant to the thing to be allocated (virtue or excellence understood as the ability to fulfill the telos or purpose of the thing). Despite that, this answer is arguable if it is taking into account that there is no consensus about the meaning of merit for Aristotle because he never defined it. At least in the distribution of the flutes, the conclusion would seem to work, but if hypothetically a slave or a stranger had more virtues with respect to a political office, would they deserve the flute? The answer in this case would be negative because, although excellence is the most important part of the meaning of merit in distributive justice, Aristotle says that political virtue (the exercised virtue in political life) cannot be exercised if it is not supported by external means. Thus, without freedom and wealth, a slave or stranger would not be able to hold a public office. Merit, in the ideal political regime for Aristotle (the aristocracy), would take into account the virtue complemented with freedom and wealth.28

Finally, if equality in Aristotelian distributive justice is based on the proportionality between the merit of a person and the purpose or telos of the thing to be adjudicated to her, then, how would the Aristotelian distributive justice deal with the socio-economic inequalities that are discussed by modern theories of justice? Of course, a logical consequence of the Aristotelian distributive justice is that it could only remain immobile before the claims of material equality: socio-economic inequalities would be justified because the only thing that matters to Aristotelian distributive justice is that the rule of distribution according to merit is not affected.29 Thus, neither the rich are called to share their wealth with the poor nor the State is called upon to make distributive policies on wealth: the rich have wealth because they have worked hard to obtain or preserve it (if it has been inherited), and have been prudent in their investments; in addition, such inequalities would be naturally justified because of, e.g., the race, the education level, or wrong decisions.30 In short, social inequities are the product of the difference in excellence to deserve the means that the wealthy possess; the purpose of distributive justice is not to satisfy the needs of the poorest, vulnerable, and marginalized people of society, but to give each one what she deserves according to her excellence with respect to the thing to be allocated.

2. The Evolution of Distributive Justice as Social Justice: Three Stages

A. First Stage of Social Justice

In the first stage, which extends to the beginning of the 20th century, the expression “social justice” was born in Europe at some point in the Old Regime, and was used to refer to “the justice of society,” that is, the justice that had to regulate the relations between the individuals that compose society, and did not denote any relation with the idea of obligatory minimum means, human dignity, or material equality, because, in that aristocratic and hierarchical society, although the concern that the poor also needed some means to survive was not ignored, Christian morality argued that the division between the rich and the poor was a natural distinction created by God, and any donation to the poor to alleviate their suffering was an issue of Christian charity (form caritas, Latin word for “love”) rather than justice, which was either corrective or distributive in an Aristotelian sense.31 Some references to the use of the expression according to the context of this period can be found in articles of journals published with the mission of spreading the spirit of the Enlight-enment, in which, for example, they refer to social justice as an obligation of the monarch,32 and in works by Catholic theologians.33

According to Fleischacker,34 at least in Philosophy, it was not until Adam Smith and his book “The Wealth of Nations” of 1776,35 that this conception of the poor, as those condemned to be poor in the earth and to be hierarchically inferior and disdained by their behavior, began to change because Smith suggested a change of attitude towards the poor by saying that they also possessed the same intellectual capacities, virtues, and ambitions like any human being. By the early 1790’s, claims of equality in aspects such as the right to work and education, came to constitutionalism, particularly in the Constitution of France of 1793,36 and, although, like many others, François Babeuf was already talking about a natural right to an equal enjoyment of wealth,37 there is no evidence that the term “distributive justice” or “social justice” has been used in this sense.

Traditionally, it has been pointed out that the expression “social justice” was coined in the mid-nineteenth century by the Jesuit priest Luigi Taparelli D’Azeglio;38 however, as seen, the use of the expression is older. For Taparelli, social justice is justice “between a man and another man”, which demands, as they are both equal in specie by God (both are equal in humanity), they must be equal in rights even though, concerning their individuality, they are different by nature (e.g., some are more intelligent, others are stronger, etc.).39 Taparelli says that social justice is divided between commutative and distributive justice: the first one balances the quantity of assets to which someone has a right in a private relation (e.g., if someone acquires an asset, she has to pay for it; the right must be satisfied with something equivalent), while the second one balances the proportion in the distribution of the common good (e.g., an office in government must be assigned to the most skilled person, not to anyone).40 So, it is not true that Taparelli did coined the modern sense of the term “social justice” because his definition of social justice followed the typical features of this stage: social justice is the “justice of society”, which is understood in an Aristotelian sense and, by consequence, divided between corrective (or commutative, according to Tomas Aquinas) and distributive justice.41 In the same way, in the Anglo-Saxon world, John Stuart Mill used the expression “social and distributive justice” in his essay “Utilitarianism”; however, as Taparelli did, that expression was understood in an Aristotelian sense.42

However, as United Station professor Thomas Burke clarifies,43 Taparelli’s conception about morality in the economy equivocally transcended as Taparelli’s concept of social justice and influenced the way that expression was to be understood later. Taparelli’s economic doctrine suggested a confrontation between the economic liberalism and the ideal or catholic economy, which is the one he prefers. In the first place, he considered that the individualism of the former condemned society to a permanent war (e.g., producers against producers and buyers), leading to demands for redistribution and communism; second, the ideal economy was preferable because it was based on the presumption of society as a community, founded on respect for the person and charity, and where, as an accomplishment of the latter, the rich (not the State) were responsible for providing the poor with the goods they needed to survive. Therefore, the role of the State was to protect the social order both from the cruelty of the powerful (e.g., big industrialists) against the poor, and also from the communism promoted by the poor, which rose up against the powerful.44 Thus, in general terms, it can be said that the roots of the meaning of social justice that eventually became globalized can be found mainly in the doctrines of a conservative Catholic political sector that was against the individualist laissez-faire of the capitalist Industrial Revolution and against the radical communist demands for a greater economic equality, especially for the benefit of the poorest sectors of society.

B. Second Stage of Social Justice

This “Taparelli’s meaning” of social justice evolved in such a way that it became a third way to liberalism and communism, according to which a qualified type of poor, workers, should have the right to some minimum means to be able to exercise their work without the abuse of their ambitious employers and to minimum conditions of life to develop themselves as persons. Now, this is the second stage of social justice, which extends from the first decade of the twentieth century to the middle of the same century approximately.45 There are some fundamental documents to understand this transit towards the transnational consolidation of social justice as “an obligation of the State and also of the employers, to provide some minimum means so that the workers can live with dignity” are:46 political scientist Westel Woodbury Willoughby’s book, Social Justice: A Critical Essay, which says states that the problem of social justice is both “the proper distribution of economic goods… and the harmonizing of the principles of liberty and law, of freedom and coercion,” and that is the first verifiable definition of social justice which expressly relates it with the distribution of assets;47 the preamble of the Constitution of the International Labor Organization in 1919 (the first establishment of that expression in a legal document in world history);48 the encyclical “Quadragesimo anno” by Pius XI (named after the forty years of “Rerum novarum”),49 written by a pupil of a Taparelli’s pupil,50 in which the Catholic Church officially incorporates social justice into its “social doctrine”, by saying that it is an institution that orders, for example, that workers’ wages must satisfy the needs of their families, including education, and that they cannot be diminished in order to increase the wealth of the employers, because social justice condemns the excessive accumulation of individualist capitalism; and finally, the encyclical “Divini redemptoris” also by Pius XI,51 according to which social justice, from whose rules no one can escape, demands that, for society to function, all members of society, endowed with the dignity of the human person, must have all the means to be able to fulfill their particular social function, just as the parts of an organism are interdependent and they need their means so that they can give life to it. In this way, the notion of social justice starts to be linked to human dignity explicitly and continues its path to become a constitutional and international rule as explained by Samuel Moyn above. Also, this was the context in which the principle of Social Rule of Law was born as explained above too.

In the constitutional domain, the Constitution of Ireland became the first one to enshrine the expression “social justice” by stating that the exercise of the natural right to private property “ought, in civil society, to be regulated by the principles of social justice”.52 The next one was the Constitution of Costa Rica in 1949, which, by following the typical Christian sense of the term in the second stage, enshrined social justice as a principle of social rights such as to have a job and a family.53 Finally, the preamble of the Constitution of India in 1949 enshrined social justice, together with economic and political justice, as a purpose of the State itself. Now, this is an example of the diffusion of the expression “social justice” beyond the explicit influence of the tradition of Catholic thinking in constitutional law; so, further research is encouraged to unveil the origin of “social justice” in the Indian Constitution.54

Thus, as suggested before, it is necessary to make some precisions about two transcendental concepts in contemporary constitutional law, which, as seen, are linked with the arise of social justice in the world and which, eventually, would become the legal tools through which the State will try to materialize social justice itself: the principle of Social Rule of Law, and the principle of human dignity.

a. The Principle of Social Rule of Law

The Social Rule of Law is a legal institution that arose as a result of several reactions against the classical legal thought of the late eighteenth century, which spread to Europe, America, and other parts of the world during the nineteenth century and conceived the Law (and the State) as an individualistic system, a consequence of a “socio-Newtonian” conception of society.55 Because of the deepening of the effects of the Industrial Revolution, there was a need to respond to phenomena such as the exploitation of workers, the growth of misery, and health problems in the cities, etc. Thus, at the end of the nineteenth century, the social question arises as a concern to solve the problems attributed to that individualist perspective of society, which also ignored the interdependence among all of the components of society.56 Then, a labor and social security legislation emerged with ideas such as social function of property, among other aspects, which marked the beginning of a State engaged with two purposes: the preservation of the Rule of Law and its liberal and capitalist values, as opposed to the communists’ pretensions, and, second, the establishment of certain minimum means for people to exercise their rights of the first generation (i.e. civil and political rights), in order to prevent communist popular uprisings.

In spite of these advances, which can be first verified in the Constitution of Mexico and, later, in the Constitution of Weimar,57 the principle of Social Rule of Law was not expressly enshrined at the constitutional level but after the promulgation of the Constitution of France in 1946,58 the Constitution of the State of Bavaria of 1946,59 and the German Basic Law,60 and, in Colombia, in article 1 of the Constitution that includes the progress made in social rights by the constitutional amendment of 1936 to the former Constitution.61 It is worth pointing out that the use of the expression “Social Rule of Law” (Sozialstaat in German), although not used at the beginning to denote all the characteristics that today are attributed to the Social Rule of Law, was popularized in Germany after World War I by the social democrat legal scholar Hermann Heller.62 However, its theoretical background may be found in previous works by Lorenz von Stein almost a century earlier.63 By contrast, in the Anglo-Saxon world, there is no such a principle of Social Rule of Law in the constitutional discourse, and that cannot be assimilated with the Welfare State, a set of economic measures undertaken by the federal government of the United States to overcome the Great Depression of 1929 through the State intervention in the national economy. Summarizing, it can be said that a Social Rule of Law is a Rule of Law in which social rights are enshrined as a complement to civil and political rights, and whose purposes are to preserve the liberal values of the Enlightenment revolutions and to ensure some minimum material means for the exercise of civil and political rights.

b. The Principle of Human Dignity

The expression “dignity”, in Latin “dignitas”, was used by the Romans to imply the social status of someone in life and the honor due by that status. At least two traditions with a different sense of human dignity can be mentioned in European philosophy: the Catholic and the Kantian. According to the former, starting from Thomas Aquinas, this expression was used as the intrinsic value of something (not only the human person, at least until 1937 because of the encyclical Divini Redeptoris by Pius XI)64 with respect to its place in the hierarchy of God’s creation. For example, women and animals would have a lesser intrinsic value than a Catholic man, and even the Catholic sacraments would have a greater dignity.65 In the second one, starting from Immanuel Kant, in philosophy, dignity (Würde in German) began to be understood as the intrinsic value of every human being, because they have autonomy (a moral law given by their own), which prevents their instrumentalization by no one.66 Now, two theories on the first constitutionalization of the expression “human dignity” can be mentioned: those of German scholar Bernd Marquardt and American scholar Samuel Moyn.

According to Marquardt,67 the first modern constitutionalization of human dignity is found in the Bavarian Constitution of 1946,68 where it was mentioned as one of the elements that did not take into account the former Nazi State and as an inviolable obligation of the State. In addition, Marquardt says that this constitution took up the expression “dignity”, which was enshrined for the first time in the Weimar Constitution of 1919,69 where it was prescribed that economics should be governed by “the principles of justice” (an expression that, by its time, context, and environment, does not seem to refer to the Aristotelian notion of distributive justice) to guarantee human conditions in accordance with dignity.70 Finally, Marquardt seems to suggest that the Fundamental Law of Federal Germany was more influential, in the later transnational constitutionalization of human dignity,71 and he says that, with respect to the female population, the emphasis on human dignity in the subsequent decades was the key to gender equality, for example, in societies with patriarchal traditions such as the Catholic ones and those with a Napoleonic Civil Law tradition.72

On the other hand, scholar Samuel Moyn has attempted to demonstrate that the Irish Constitution,73 by its fervently Catholic framers that wanted to follow the indications given by the papal encyclical Divini redemptoris -which denounced the atheistic communism-,74 was the first constitution in world history to proclaim the individual dignity of the human person as a founding principle of the State. Of course, dignity was still interpreted according to the context of the Catholic doctrine of the time, opposed, for example, to recognizing the total equality of women vis-à-vis men, especially in the traditional Catholic patriarchal home.75 Moyn’s central idea is that this constitution is important because it reflects a historical fact that no current scholar has noticed, namely that the inclusion of the expression “human dignity” in the contemporary global constitutional discourse was spread from the tradition of Catholic thought about dignity and not from the Kantian tradition, as it is currently broadly believed. According to Moyn, in addition to the Irish one, it was enshrined later in the constitution of the largely Catholic State of Bavaria,76 as in Ireland, by the influence of the Catholic thought of this period, and globalized, totally secularized, thanks to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,77 in which the inclusion of the expression “human dignity” was due, to a large extent, to the influence, on its writers, of the frequent use of the expression “dignity of the human person” by the Pope during World War II, and, again, not to the Kantian tradition of dignity.78

Nevertheless, today, the Kantian tradition is preferred when interpreting the expression “human dignity”. Therefore, all the current debates on justice deal with the best distribution scheme and it is not disputed if all people have equal worth when they are taken into account to be subjects of distributive justice; that is to say, it is taken for granted that all people have a dignity that cannot be ignored and must be respected when they are to be allocated rights or means, an aspect that was in discussion in Aristotle’s times.79 Thus, egalitarians, like John Rawls,80 argue that the best distribution scheme is one where benefits are guaranteed to the most disadvantaged, contrary to libertarians, like Robert Nozick,81 for whom there should be no distribution by the State because it would be against individual freedom.

C. Third Stage of Social Justice

In the third stage, which extends from the mid-twentieth century to the present, the notion of social justice has been expanded from the context of labor relations thanks to the evolution of affirmative actions, the international establishment of a catalog of economic, social, and cultural rights (as a duty of the State to guarantee a certain level of minimum means to allow people to exercise their civil and political rights signed but not ratified by the United States),82 and the discussion on the adoption of differential treatment to the benefit of the poor in income and wealth as part of social justice.

The term “affirmative action,” in its modern sense, stems from the Executive Order 10925 by USA President J. F. Kennedy,83 in which all contracting agencies of the government were ordered to apply affirmative action to ensure that both applicants and employees were treated equally regardless of race, creed, color, or origin (note the link between the expression “affirmative action” and labor). However, this expression was already somewhat common in the American language in the same labor relations slang (see its previous use in Figure 12 below). This understanding of affirmative action as an instrument to fight discrimination and achieve equality of opportunities allowed the expression to be applied to measures with the same purpose taken, in addition to the government, by the Supreme Court of the United States, for example, in the case “Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,”84 that allowed universities to include race as an admission criterion in order to achieve greater diversity, and, indirectly, to provide more opportunities to groups traditionally discriminated, in line with the precedent of the case “Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.”85

In this period of increasing affirmative action in government and the judiciary in the United States and then in the rest of the world, John Rawls’ very influential book in philosophy, Law, politics, and economics, “A Theory of Justice”, was published in 1971 and revised throughout his life. In this work the expression “social justice” is used to refer to the very notion of distributive justice that he uses there,86 and whose core is the principle of difference, according to which socio-economic inequalities in an ideal well-ordered society are justified if they work for the benefit of the least advantaged in society, which are not women, the elderly, nor the traditionally marginalized people, among others, but those who, although sharing with other people equal liberties and opportunities (the first principle of justice and the first part of the second principle), have less income and wealth, i.e., the poor.87 So, it is important to clarify that Rawls’ social justice did not include as one of its main aims to overcome the discrimination and marginality present in the non-ideal sphere of the theory, that is, in the real context of the American society and other liberal societies of the time, as the promoters of affirmative action had actually in mind.88

Most contemporary constitutions that enshrined the expression “social justice” as a purpose or principle of the State did it in this stage, i.e., from the seventies to the second decade of this century.89 So, even though social justice, as a third path between communism and laissez faire capitalism, arrived into the contemporary global constitutional discourse from the Catholic thought just like human dignity, the Christian heritage is not evident at all in the third stage, which has also favored the expansion of the expression in contemporary constitutional discourse throughout the world. Today, social justice is not only used in the labor discourse, but also in the field of affirmative actions for the discriminated, the vulnerable, and the marginalized. In the discourses that promote the achievement of social, economic, and cultural rights, and in those discourses that encourage a differential treatment by the State to benefit those with lower income and wealth. These last features make up the contemporary notion of material equality (as opposed to formal equality).

Summarizing, these are the three basic elements which constitute the current meaning of social or distributive justice in contemporary comparative constitutional discourse: i) the Social Rule of Law as a duty of a new kind of State, which must guarantee or allocate some minimum means so that people can subsist, ii) the acknowledgment of the human dignity of people, and iii) the duty to promote affirmative actions in order to guarantee the poor, the marginalized, the discriminated, and the vulnerable, an equal opportunity to develop their life plan, i.e., the warranty of the right to material equality.

Just like the principles of social rule of law and human dignity, it is necessary to clarify the meaning of “material equality” as a right, which is also a transcendent element both in the configuration of the current understanding of social justice and in contemporary constitutional discourse.

a. The Right to Material Equality

In contemporary constitutional discourse, the expression “material equality” has been generally understood as a duty of the State to promote affirmative actions, so that equality remains not merely formal as it was before the enshrinement of the socio-economic-cultural rights, in order to overcome socio-economic inequalities to benefit the poorest in income and wealth, but also the traditionally discriminated and marginalized sectors of society.90

Although there is no certainty about the first use of the expression “material equality” in the global constitutional discourse, some early sources and similar in meaning like the described in the previous paragraph can be found both in France and in Germany at the end of the nineteenth century.91 The modern use of this expression in English can be verified in the Austrian economist Friedrich A. Hayek’s book “Road to Serfdom” in 1944;92 of course, he uses it in a context of criticism towards centralized or collectivistic economic planning.93

Nevertheless, just like the principle of Social Rule of Law, the expression “right to material equality” is not present in the Anglo-Saxon constitutional discourse and, actually, its conceptualization and use are part of the European and Latin American civil law tradition. Of course, this doesn’t mean that, in the Anglo-Saxon constitutional discourse, there are no ways to realize the purposes that the right to material equality has in other parts of the world.94 That is why, in Latin America, the constant use of the expression can be verified, for example by the Colombian Constitutional Court since 1992.95 In fact, it is also used interchangeably with others just like “real and effective equality” (as it appears in Article 13 of the Colombian Constitution) or “substantial equality”.96 Also in Latin America, the first constitution worldwide that enshrined the right to material equality as opposed to formal equality was the Constitution of Ecuador in 2008.97

However, no conclusive proof can be given about the original source of inspiration for the modern use of this expression. So, it would be interesting to continue looking for the primary sources of its inspiration to determine when they began to be used to mean a different right to that of formal equality before the law; nevertheless, this is beyond the scope of this research.

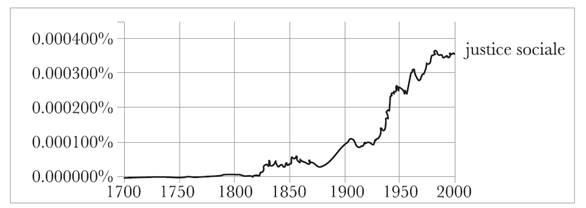

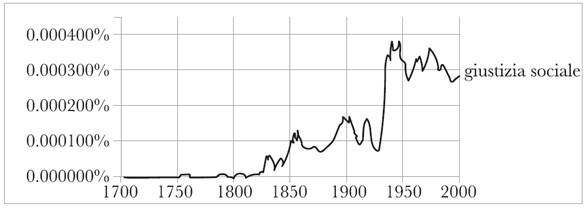

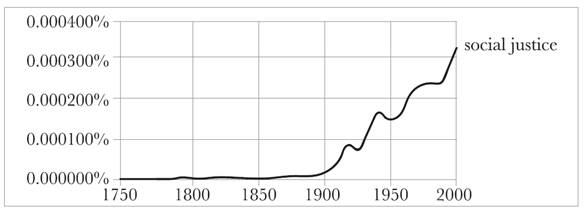

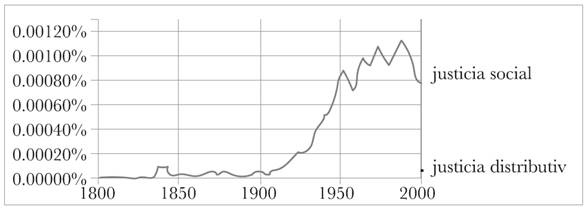

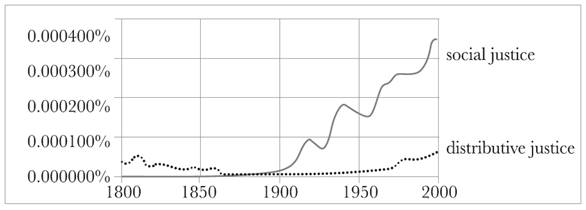

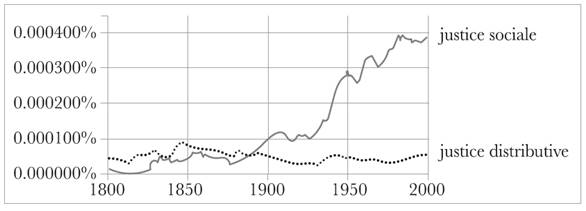

D. Social Justice in Google Ngram Viewer

Some graphs can be shown to illustrate the tendency of the use of the expression “social justice” thanks to Google Ngram Viewer, a novel technological tool for research in social sciences, which displays an approximate evolution of the frequency in the use of a word over time in several books in different languages.98 It can be seen that the use of the term “social justice” is older in French (Figure 1) and Italian (Figure 2) than, for example, in Spanish (Figure 3), English (Figure 4), and German (Figure 5).

In all these languages, the use of this term increased in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, i.e. at the beginning of the second stage of its evolution, and, despite valleys that could be due to reasons of different nature, which are not pertinent to discuss here, it is important to note that it shows that its use grows after World War II, when the notion of social justice of the second stage is consolidated, arriving at its highest peak in the 1980’s, when social justice was strengthened by the ascent, first in the United States, and since the 1970’s in the rest of the world, of the discourses of affirmative actions (with its ideals of non-discrimination), equal opportunities, and distribution of wealth and income for the poor or disadvantaged. However, it still remains to be known why its use has a moderate downward trend in Spanish and Italian, and not in English or French, its use has a moderate downward trend.

On the other hand, it can be seen how the notion of social justice did not echo so much in Russian, the majority language in the main communist country in the twentieth century, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and that is because the notion was typically used in those legal-political discourses that stood against Communism (Figure 8). However, as a way to set up here a debate that can be developed later, there is a timid rise of the expression during the 20’s and 40’s, which coincides with the emergence of important documents in other parts of Europe, which contain the expression “social justice” as described above. Moreover, it is noteworthy to mention that only after the collapse of the USSR and its opening to the capitalist and liberal bloc, the expression has a vertiginously upward trend that has been declining for some time.

Finally, if the frequency of the use of the expression “social justice” in Spanish, English, and French is compared with that of “distributive justice” in the same languages (Figures 7, 8, and 9), it can be concluded that the first expression has been more popular than the second one starting from the second stage, a phenomenon that may be explained by the fact that the expression “social justice” began to include distributive justice by this time, as explained above.99

E. Social Justice in Latin American Constitutions

The first Latin American constitution that used the expression “social justice” was the Constitution of Costa Rica in 1949, which followed the typical Christian sense of the term in the second stage.100 Nevertheless, the expression was popularized in the Latin American constitutionalism in the current third stage of its evolution, in which the theological component is not evident yet.101

So, the Constitution of Panama enshrined social justice as an element that the right to education must foster, and as a purpose to be effective by the State when intervening in enterprises.102 The Constitution of Cuba decreed the right to social justice as the purpose of the republic.103 The Constitution of Honduras stated that the “principles” of social justice are the foundation of the economic system and the objective to be guaranteed by the process of agrarian reform in rural areas.104 The Constitution of El Salvador included social justice as a duty of the State and a founding principle for labor rights, social security, and the economy.105 The Constitution of Guatemala decreed that the labor law and the social and economic orders are organized based on the “principles” of social justice.106 The Constitution of Brazil established that the economic order has to guarantee a dignified existence, according to the principles of social justice, and that the social order (social security and health) must achieve social justice.107 The Constitution of Paraguay enshrined social justice as a purpose that the right to education must promote.108 The Constitution of Argentina ordered the Congress to legislate in order to achieve economic development with social justice.109 The Constitution of Venezuela decreed social justice as a purpose of the State and one of the principles in which the economic regime is founded.110 The Constitution of Ecuador asserted that social justice is the principle in which the right to the enjoyment of city and its public spaces is founded.111 The Constitution of Bolivia enshrined social justice as founding purpose of the State and as one of the purposes both of the State when carrying out its functions and the higher education.112 And, recently, the Constitution of the Dominican Republic declared that social justice is a founding element both of the functions of the State and of the economic regime.113

The most important exceptions of this tendency are Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Colombia, which could be studied by future researchers that analyze the political, ideological, and legal causes which determined that, in some countries and not in others, there had been a consensus to expressly constitutionalize the term “social justice”.

III. Social Justice in Colombian Constitutional Discourse

The reception of the notion of distributive or social justice in an extended sense in Colombia can be verified in the debates that led to the enactment of the new Constitution in 1991.114 In the Gaceta Constitucional (Constitutional Gazette), the official newspaper that published the projects and proposals discussed in the National Constituent Assembly, it can be seen how the notions of human dignity, affirmative actions, and social justice were expressly used according to the discourse of the social stage in an extended sense. Thus, some constituents understood social justice as one of the main purposes of the Social Rule of Law,115 by comparing it with the full warranty of labor rights (both individual and collective), according to its use in the Catholic social discourse of the second stage,116 and by understanding it as an essential purpose of the intervention of the Social Rule of Law in the economy.117 One year later, the Constitutional Court decided the Judgement T-406 of 1992, in which it mentions both social and distributive justice as a matter of allocation of means with the aim of guaranteeing social rights in the new Social Rule of Law.118 So, it is possible that social justice or distributive justice can be considered, at least implicitly, as an aspiration of the Colombia Social Rule of Law, and which, according to the Court’s jurisprudence, has been understood as a “constitutional purpose,”119 although it has not been expressly established in the Constitution. However, its express establishment as a purpose, a principle, or even a constitutional right corresponds to the competence of the constituent power, whether original (the people through a National Constituent Assembly by drafting a new Constitution) or derivative (the congress through an amendment to the Constitution). Nevertheless, the 1991 Constitution enshrined the three elements of social justice described above as will be shown in the next three items.

1. Social Justice in the Constitution of 1991

A. The Principle of Social Rule of Law

Article 1 of the Constitution describes Colombia as a Social Rule of Law,120 whose main purpose is to guarantee some minimum means for the exercise of civil and political rights, as discussed earlier. Many books, articles, and judgments have defined this principle enshrined by the Constitution,121 but what is important to note here is that, since the beginning, the main interpreter the Constitution, the Constitutional Court has pronounced on the essential purpose of this kind of state mentioned above, and it has identified it as the sense of social or distributive justice that derives from a Social Rule of Law such as the Colombian one:

if it were necessary to give an abstract judgment on distributive justice... one could resort to the principle of equality, …from which all distribution of means, in order to be just, should, at least, improve the social position of the most disadvantaged. In other words, distributive justice must be considered as a problem of distribution -of allocation by the State- of new means available, whose final result, whatever the beneficiaries or those affected by such distribution may be, does not spoil the situation of those who have fewer means.122

In the legal system, evidence of this principle of Social Rule of Law as a duty to guarantee some minimum means to allow people exercise their rights can be found in the Constitution itself, which has an entire chapter devoted to social, economic, and cultural rights,123 and an article on the State intervention in the economy in order to guarantee the fair distribution of opportunities and other objectives,124 and in other norms such as the acts on social security,125 higher education,126 etc.

B. The Principle of Human Dignity

Article 1 of the Colombian Constitution enshrines the principle of human dignity as a founder principle of the Social Rule of Law. This precept is not a mere aspiration of the constituent or a symbolic text, but a binding legal rule.127 In several judgments, the Court has emphasized human dignity as a fundamental principle and right of the Constitution and the Social Rule of Law; human dignity is an inherent attribute of the human beings, which makes them the creditors of minimum rights in order to guarantee their development in the best conditions.128

Furthermore, this principle is i) a mandatory hermeneutical directive for all public authorities, ii) an absolute a priori principle, that is, it cannot be limited or downplayed, like other principles and rights;129 and iii) a direct normative source of fundamental rights both enshrined in the Constitution and non-enshrined expressly.130 It is important to clarify here that fundamental rights are also understood as the economic, social, and cultural rights recognized by the constitutional jurisprudence, such as the right to health and to a vital minimum, because of their deep and indissoluble connection with the human dignity itself.131

An example of the scope of human dignity is the Judgment C-177 of 2001,132 in which the Court established a public lawsuit of unconstitutionality against a part of article 322A of the Criminal Code, which enshrined that the crime of genocide did not protect illegal groups, e.g., guerrillas. The Court declared the unconstitutionality of that part of the rule, motivated by the fact that it was against human dignity because it set up a limitation to the inalienable rights that every person has by virtue of being human,133 which cannot be restricted even if the acts of the persons involved are outside the Law; i.e., everybody has some inalienable rights based on their human dignity, which must be guaranteed regardless of their degree of contribution to the common good or, “emulating” the Court, “regardless of whether they deserve those rights or privileges”.

C. The Right to Material Equality

As a development of the principles of human dignity and solidarity,134 article 13 enshrines the right to “material equality”.135 This expression has been frequently used by the Constitutional Court in its judgments since 1992 when it refers to the right that every Colombian has to demand from the State affirmative actions to overcome socio-economic inequalities of the poorest, vulnerable, and traditionally discriminated or marginalized sectors of society.136

In fact, most of the Court’s judgments on social rights in the last two decades grant the protection of the right to health when the Health Care Service Providers (Entidades Promotoras de Salud) do not guarantee the right to health service access to the plaintiffs, especially when they have low economic means, poor means of subsistence, or are subjects with a special status in the Constitution (children, pregnant women, old men or women, etc.). This is a clear accomplishment of the fundamental right to material equality in Article 13: the State must guarantee the right to real and effective equality of opportunities in the protection of rights and access to offices, especially if they are subjects in conditions of vulnerability.

2. Unveiling Constitutional Meaning of Social Justice

So, the modern notion of distributive justice or social justice and not the ancient or Aristotelian one is an implicit idea in the Constitution, because the latter enshrined the three main elements of such a modern notion, i.e., the principles of Social Rule of Law and human dignity, and the right to material equality, which were available in the global and national constitutional discourse of the years in which the Constitution was enacted. This exercise allows to construct a notion of distributive justice that, contrary to the Aristotelian one, is in accordance with the Constitution and can be applied by all public authorities, not only the Court, and citizens when they are asked how social justice should be understood in the Colombian constitutional discourse. It is not intended to give an incontrovertible definition, but rather to present a concept that can be used to i) clarify a diffuse notion in the Colombian legal system, ii) interpret and apply it more consistently with the Constitution, and iii) generate an intense debate about the notion itself (both in scholarly circles and in those sectors that have the power to make the Law). Recently, for example, the same Constitutional Court has brought to the Colombian constitutional debate the concern for an “environmental justice,” thus complementing the anthropocentric approach to distributive justice by ruling that the use of natural resources must be made in a sustainable way, ensuring that their exploitation generates the least negative environmental impact so that both present and future generations can enjoy the environment on equal opportunities.137 However, the fulfillment of environmental justice requires the concomitant materialization of distributive justice, which is one more reason why all the legal agents in the Colombian legal system are sure about the essential meaning that the expression social or distributive justice must have if it is going to be used in the Colombian constitutional discourse.

Thus, all public authorities and citizens are called to understand, interpret, and apply the constitutional distributive justice in the Colombian constitutional discourse, at least, as follows: the social justice of the Colombian Social Rule of Law is a duty of the State to guarantee or allocate everyone, by virtue of their human dignity, some minimum means so that they can exercise all their rights and fulfill their life plan, and a material equality through the application of affirmative actions, which consist of a distribution of rights in equal opportunity and always for the benefit of the most disadvantaged in the society, that is, the poor, the vulnerable, the discriminated, and the marginalized.

The above definition shows that, in the current constitutional order, it is not congruent to turn to Aristotle, for example, to define the meaning of social justice in the constitutional discourse, and that the demonstration of the implicit presence of a modern notion of distributive justice in the Constitution is a more complex exercise than the simple textual comparison between John Rawls’ principles of justice (from which modern debates on distributive justice start)138 and the constitutional text, as some scholars have already stated.139 Also, it is important to emphasize that any approximation to the meaning of distributive justice in the Colombian constitutional discourse cannot be understood only from a single discipline (e.g., political philosophy) or from a single group of “fashion authors” -which, ultimately, are the product of their own historical context- (John Rawls, Jürgen Habermas, etc.),140 because such exercise needs i) the comparative historical contextualization of the received discourses about social or distributive justice in Colombia, and, of course, ii) the analysis on the presence of their essential elements in the Constitution, as this paper has attempted to make.

Now, the question about the minimum means of social justice is an issue that contemporary political philosophy is currently debating, for example, from the Rawls’ approach on primary goods,141 the alternative approach centered on capacities formulated by Amartya Sen,142 and the ideas about material contents of distributive justice demanded at the international level.143 However, the answer to the Colombian constitutional case should not only be based on these theoretical references, since, above all, a “list” of vital minimum means guaranteed by the Social Rule of Law must be the result of the political struggle for its recognition by the Colombian society, in arenas such as the legislative and the executive branches of power, according to the need to resolve the problems that the society itself has and without depending on a decontextualized theory that ordains the explicit content of such a “list”, allowing, in turn, a strengthening of participatory democracy that counterbalances the Court’s marked judicialization of politics in deciding the content, scope, and enforceability of social rights, without depriving it from this function.

Furthermore, it is important to clarify that, although many of the components of this notion of social justice have some antecedents in the Catholic Church’s tradition of thought, this does not imply that the interpretation of these components must be done based on this religion. Nor does it mean that the components should be rejected because of their origin, despite their potential to materialize the Social Rule of Law, which is achieved if they are interpreted and contextualized within the framework of the Constitution.

So, it can be said that, as social justice or modern distributive justice is implicitly contained in the Colombian constitutional law, it is not an extra-systemic element neither an absolute idea, because, although it is not established by a specific rule, its components are Constitutional rules of mandatory compliance.144 Actually, the same exercise can be done in other countries which have no purpose or principle of social justice in their constitutions such as Mexico or Chile, in order to identify both i) its implicit presence through the enshrinement in their constitutions of the three main elements of social justice in the transnational constitutional discourse, and ii) the legal mechanisms to materialize social justice.

3. The Exceptional Presence of the Aristotelian Distributive Justice

The jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court has understood distributive justice, in most of its trials in which it has tried to define it, according to its modern sense. Nevertheless, there are some judgments where the Court has used a very unusual mixture of the corrective justice in an Aristotelian sense and the distributive justice based on merit (i.e. the amount of contributions to the common good, the Court’s definition of merit).

In Colombia, there are no scholarly works about the presence of the Aristotelian notion of distributive justice in the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court. For instance, Alejandro Matta, in his paper on the influence of Aristotle in the Court’s judgments, only briefly analyzes the value of justice for Aristotle, by saying that his ideas have been followed by the Court in some judgments as a tool aimed to overcome a norm-centered hermeneutic, but he doesn’t identify how the main features of the Aristotelian notion of distributive justice has been applied in its jurisprudence.145

The methodology used to select the “Aristotelian” judgments was as follows: first, on the Court’s web page, all judgments which contain the expression “distributive justice” were searched; then, those judgments which define the distributive justice were selected; after that, each one was studied with the aim to determine the sense of distributive justice contained in them, i.e., an Aristotelian or modern sense. Finally, these cases were classified by year and their category of distributive justice, and were organized in the following table. The “Aristotelian” judgments are marked with an asterisk.

Table 1 Colombian Constitutional Court’s Judgements Since 1992 to 2016 Containing and Defining the Expression “Distributive Justice”

| Year | Judgements |

| 1992 | T-588, T-406, C-472, T-532, T-432, T-505- T-422, C-479 |

| 1993 | T-483, C-228, T-484, T-140, C-094, C-171*, T-253, T-122*, T-236, C-002, T-292, C-260, C-006, T-574, C-197 |

| 1994 | T-290, C-372, T-563, T-411, C-266, T-467, T-525, T-463, C-547, C-069* |

| 1995 | C-028, C-136, T-113, T-165, C-419, C-430 |

| 1996 | C-251, C-59, C-036, C-080, T-715, T-566 |

| 1997 | SU-519, T-674, C-384, C-536, T-002, T-455, T-516, T-526, C-588, SU-519 |

| 1998 | T-288- C-159, T-748, T-208, T-208, C-002, T-311, T-707, C-317, C-094 |

| 1999 | C-925, T-865, T-528, C-741, T-798, C-082, C-152, C-741, C-474, T-209, C-866 |

| 2000 | T-1571, T-1134, T-1104, T-1293, C-386, T-1294, T-1730, T-1752, T-1576, T-1596, C-922, T-1451, C-392 |

| 2001 | T-1133, T-075, T-209, C-651, T-752, T-022, C-1060A, C-555, T-1154, C-1218, C-648, T-1040, C-1168 |

| 2002 | T-610, T-770, C-762*, C-184, C-261, C-109, C-615 |

| 2003 | C-482, C-1005, C-875, C-271, C-870, C-776, T-1089 |

| 2004 | C-1029, C-1054 |

| 2005 | T-640 |

| 2006 | C-741, C-666 |

| 2007 | T-065, C-308 |

| 2008 | T-250, T-1040 |

| 2009 | C-324, T-543 |

| 2010 | C-073, C-639 |

| 2011 | T-551, T-176 |

| 2012 | T-999, T-1094, C-715 |

| 2013 | T-235, T-583, T-370, T-095, T-427, C-912, T-646, T-799, C-753, C-839, SU-130, C-099, C-359, C-579 |

| 2014 | T-695, T-271*, T-600, T-565, T-682, C-616, C-180, C-286, T-294 |

| 2015 | C-044, T-606, T-539, T-080, T-191, T-648 |

| 2016 | T-112, C-209 |

According to the results of this research, two issues can be concluded: the first one is that there are five judgments in which the Aristotelian notion of distributive justice is used to base the decision: C-171 of 1993, C-069 of 1994, C-762 of 2002, C-073 of 2010, and T-271 of 2014; Judgment C-171 of 1993 is the founder of the “Aristotelian precedent” because it was quoted by the other ones. The second one is that, as there have been no changes in the Aristotelian definition of distributive justice in Judgment C-171 of 1993 throughout the years, this judgment will be studied alone in order to extract the Court’s Aristotelian notion of distributive justice. This hermeneutic methodology is known in Colombian legal academy as the static jurisprudential analysis (análisis jurisprudencial estático), as opposed to the dynamic jurisprudential analysis (análisis jurisprudencial dinámico), which consists of the interpretation of an individual judgment, not several ones over the years.146

Thus, Judgment C-171 of 1993 by Justice Vladimiro Naranjo Mesa decided the constitutionality of Decree 264 of 1993,147 which was enacted in the frame of an State of exception by internal shock (Estado de excepción por conmoción interior), declared on November 3th, 1993, with the aim of fighting criminality through the implementation of some mechanisms that allowed the Attorney General to get from the defendants and convicts a greater collaboration with the State in the prosecution and punishment of the crimes related to drug growth, funding, traffic, elaboration, and promotion, the obstruction of justice by public authorities, terrorism, and those crimes against the security and existence of the State itself (e.g., espionage) and against the valid constitutional regime (e.g., rebellion and sedition). The mechanisms that this Decree gave to the Attorney General were benefits to the collaborator such as house arrest, partial or general pardon, among others.

At least two legal problems were considered by the Court: the first was whether this Decree had violated the constitutional prohibition to modify the judicial accusation and judgment functions through a State of exception.148 The second one was whether the Decree had broken the right to equality by giving certain benefits only to some criminals and not to all of them. The Court’s decision to the first problem was that the executive modified the accusation and judgment functions because it was giving judicial functions to the Attorney General and also congressional functions such as general pardons, which are only granted in cases of political crimes. On the second problem, the Court said that the Decree made an unjustified distinction between the beneficiaries and the rest of criminals, even though the formers had committed the worst crimes according to the Criminal Code.

According to the Court, the constitutional right to equality was violated by the Decree because “it gave a more favorable treatment to certain type of criminals, paradoxically …to those who [had] committed the worst crimes against society, including crimes against humanity, such as indiscriminate acts of terrorism. There is, in this case, an evident breaking of the principle of distributive justice and commutative justice.”149 Then, the Court defined the sense of distributive justice to adjudicate this case: “in the distributive justice, it is observed the mean according to the merit of the people. But that merit is also observed in the commutative justice, for example in the allocation of punishments, because the punishment will be higher to that person who affects seriously the common good. As said before, the distributive justice allocates something among people, according to the personal merit of each one. So, a benefit cannot be granted only according to the thing exclusively, but according to the proportion of the thing with respect to the person.”150 Now, on the meaning of merit, the Court said: “the more a person contributes through his daily actions to the common good, the greater the prerogatives must be. That is to say, the objective contribution to the common good and the consistent action with the general interest must be taken into account in order to apply the principle of equality, which corresponds not to quantity but to proportion.”151 Then the Court explained that distributive justice could tolerate difference or inequality, except in cases where it is contrary to the proportional distribution of merit; the Court said that “granting some citizens a series of benefits..., excluding the other individuals from those exceptional privileges, means establishing the principle known as the “people differentiation” opposed to the equality proper to justice. In fact, the above-mentioned anti-juridical saying contradicts distributive justice since it consists of allocating the goods and the penalties to different people in proportion to their merit. Consequently, when one considers this property of the human being, by which he is given what is due to him, his individuality is not observed as much as his merit or dignity. Therefore, it is clear that the differentiation of people is opposed to justice, since adjudicating without proportion is not equal. And nothing is as much opposed to justice as inequality.”152 In this way, the Court emphasizes that, when it comes to adjudicating on distributive justice in a case, that is, allocating both property and penalties, merit is a substantial element and cannot be negotiated.153 The Court declared that the Decree contradicted the right to equality because it enshrined punitive privileges to a group of criminals -especially those who deserved it less- and denied them to the rest criminals.154

The question that arises now is: where did the Court get the concept of distributive justice from? This is not an innocuous issue because the decision on the unconstitutionality of the Decree depends on the adopted concept of distributive justice. In fact, in the other three judgments of constitutionality, the Court decided a similar issue, i.e., the unconstitutionality of a criminal act in which special benefits were given to criminals because their lesser contribution to the common good made them less deserving to those punitive benefits. And, in the most recent judgment, the Court denied a request for house arrest made by a prisoner with HIV due to his illness, and it founded its arguments also in the lack of merit of the prisoner to such a punitive benefit, even though, because of his vulnerable condition, it could be argued that his stay in prison was against his human dignity.155 Anyway, what is clear at first glance is that, in these five judgments, the Court follows the well-known “meaning” of justice: “justice is to give each one what they deserve”, i.e., the Aristotelian or ancient sense of distributive justice.

However, the Court has mixed the two types of particular Aristotelian justice, in what has been called here an “Aristotelian and corrective distributive justice”. Indeed, to the Court, distributive justice consists of the distribution of goods and penalties and is based on merit, thus falling into a substantial theoretical imprecision because the penalties, according to Aristotle, cannot be allocated depending on merit, because it is intended to correct the inequality caused by an anti-legal damage. Thus, the Court has based the unconstitutionality of the Decree in this judgment, and in the others that followed it as a precedent, on a wrong interpretation of the Aristotelian theory of justice, although it does not mean that the applied notion of distributive justice lacks Aristotelian roots. Then, by applying such an Aristotelian and corrective notion of distributive justice, the Court violates the principle of Social Rule of Law because that notion does not take into account the concern of ensuring everyone a minimum quantity of means to fulfill their life plan, which is the base of one of the essential objectives of the State itself.

Also, as it can be seen, there is also no coherence between the Court’s notion of distributive justice based on merit, according to which a person will be entitled rights and benefits from the society depending on the quantity of his contribution to the common good, and the principle of human dignity, which, applied to the idea of distributive justice, means that everyone can be a subject of distributive justice just for the fact of being human and, therefore, everyone has an equal dignity to participate in the distribution of rights available in society without relying on the merit as the quantity of their contribution to the common good. Thus, by interpreting distributive justice based on the Aristotelian merit, the Court violates the principle of human dignity and questions its absolute character because it says that it does not matter if all human beings have the same dignity to participate in the distribution of social goods, because there are always some people more dignified than others, that is, there are people who deserve more than others to be treated in a privileged way by the Law and the State.

Additionally, there is no coherence between adopting the Aristotelian notion of distributive justice -which allows socio-economic inequalities as long as equality in merit is not affected, because the most important is that there be no inequalities in merit- and the obligation imposed by the Constitution to guarantee a different treatment in benefit of the least favored in society in order to realize an effective and real equality with the same opportunities for everyone, which is the conceptualization of the fundamental right to material equality.

Thus, according to the methodology of jurisprudential analysis proposed by the Critical Legal Studies,156 such notion of distributive justice applied in this judgment allows to identify that the ideology on which Justice Vladimiro Naranjo decided this case is framed into the Natural Law, specifically in the Aristotelian-Thomist tradition. In the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas, by introducing Aristotle into the European political philosophy, conditioned the interpretation of the former in the centuries to come, which can be seen in Judgment C-171 of 1993 both in the permanence of the use of the adjective “commutative” when describing Aristotelian corrective justice, and in the addition of “the achievement of the common good” as a goal of distributive justice and corrective justice,157 something that is not originally expressed in Aristotle’s theory of justice, since he only referred to that goal as a characteristic of a good constitution or form of government.158 Justice Naranjo’s Aristotelian-Thomist ideology has also been noticed by professor Cristina Motta who has shown, in his judgments, the recurring use of the “common good” as an axiological category by which Law and justice in the Colombian Social Rule of Law should be guided.159 Also, it is important to note that, recently, the Court has revived the debate on the validity of Natural Law in the Colombian Social Rule of Law by declaring constitutional the use of “the principles of Natural Law” to interpret the Constitution in penumbra cases, against what was requested in an unconstitutionality action that sought to repeal this possibility enshrined in an article of the centennial Civil Code. However, currently, it is difficult to predict the use and effects that this judgment can have in the long term.160

Finally, it must be said that, although the Court would not have modified the declaration of unenforceability of Decree 264 in Judgment C-171 of 1993, even if a modern notion of distributive justice had been applied, since there was another reason to declare it unconstitutional as explained in the first chapter, it is important to mention that a correct interpretation in that judgment regarding distributive justice would have allowed a better protection of rights, since: i) the type of justice applicable to the case was corrective, not distributive; ii) corrective justice is not based on merit, but on the restoration of broken equality, therefore, the Court violated human dignity by considering a group of people less deserving to receive the benefits of the Decree; iii) the majority of the justices did not understand that, in this case, there was no discrimination between the defendants/condemned who profited from the Decree and those who did not, since, precisely, the State of exception was an exceptional situation in which the measures to be taken to stop violence had to be different to those envisaged in ordinary situations; and iv) a rule with a constitutional legitimate purpose was drawn from the legal system, even though it aimed to achieve peace and, through it, to guarantee the validity of all those purposes, principles, and rights of the Social Rule of Law limited by a war.161 Thus, an analysis such as that of the Court in this Judgment C-171 of 1993 and the other five, would mean now, for example, that it is legitimate to deny members of the FARC-EP and ELN guerrillas exceptional benefits for making peace, with the argument that they are persons who do not deserve them because of their low level of contribution to the common good and that the same treatment should be given to the other offenders, just as proposed by the Court in the judgments discussed here.

4. Achieving Social Justice Through Law

The application of this modern notion of distributive justice or social justice, based on the principles and the right mentioned above, can serve to empower the Constitutional Court, other authorities of the public power, and the rest of Colombians, to materialize the aspirations of the Social Rule of Law itself. In fact, the Court has already implicitly applied this notion of distributive justice to defense and has extended the social rights initially enshrined by the Constitution, thus guaranteeing its validity as full rights.162 Thus, both the Court and other public authorities can continue or, if they have not done it yet, begin to materialize the Social Rule of Law, by applying the notion of social justice proposed here, either i) in cases among individuals, in which the persons or groups may be in a condition of vulnerability or marginality (the displaced before the measures of eviction without alternatives of relocation by the public administration, the child or elder before the adult, the woman before the man, the afro-descendants or indigenous people before the whites or mestizos, the homosexual before the heterosexual, etc.), ii) in cases where the other branches and agencies of the public power try to restrict the progression of social rights, for example, by implementing a specific economic model that is not in accordance with the distributive justice of the Social Rule of Law, or iii) when making an act, e.g., by enacting a tax reform on income with a progressive tax that allows a redistribution of wealth to social programs that promote the general welfare, especially of the poorest, one of the verifiable achievements of the Social Rule of Law in the last century to overcome inequality, and from which very relevant lessons for today can be drawn.163 Finally, by knowing the meaning of social justice and what is necessary in order to achieve it through Law, individuals and civil society in general can use legal arguments to demand the State a broader guaranty of their constitutional rights, without forgetting that they are also responsible for the materialization of the same justice, e.g., through the respect for the human dignity of their peers, the elimination of behaviors that encourage discrimination and marginality, the execution of practices to increase the efficient expense of the limited resources that the State assigns to the fulfillment of social rights without corruption, among other aspects.

So, it is clear that also in the family, the school, the university, the political arena, the policy making, etc., it is necessary to promote the constitutional meaning of social justice and to avoid using the common idea that social or distributive justice is “to give each one what they deserve”, an idea of a slave and a non-egalitarian society in which Aristotle lived, that does not materialize the purposes, principles, and rights that govern the Colombian Social Rule of Law.