| Table of contents | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | Introduction | 130 |

| II. | Mexico and Mediation | 132 |

| III. | Mexico - USA and Family Mediation in International Parental | 135 |

| IV. | Conclusions | 139 |

I. Introduction

The border between Mexico and the United States of America (USA) measures over 3,000 km long, making it the world’s longest divide between a developed and developing nation. Unsurprisingly, this shared border has given rise to millions of yearly border crossings - 11,500,000 Mexicans in the U.S.; 738,103 Americans in Mexico -seeking better economic, educational and professional opportunities. This situation also encourages interactions and an increased number of international families, that is, families formed by individuals who are under the jurisdiction of different countries.

Table 1 International Migration. Mexican Residents abroad by Country

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| United States | 11.500.000 |

| Canada | 63.395 |

| Spain | 16,864 |

| Guatemala | 14,481 |

| Germany | 14.156 |

| Bolivia | 8.556 |

| United Kingdom | 8.000 |

| Costa Rica | 7.500 |

| Netherlands | 4.656 |

Source: Instituto Nacional de Inmigración de México (INAMI), 2015.

Table 2 Foreign Population in Mexico by Country

| Country | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 | 1980 | 1970 | 1960 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 738.103 | 343.591 | 194.619 | 157.08 | 97.248 | 97.902 |

| Spain | 77.069 | 21.024 | 24.783 | 32.240 | 31.038 | 49.637 |

| Guatemala | 35.322 | 23.957 | 45.005 | 4.115 | 6.969 | 8.743 |

| Colombia | 14.942 | 6.215 | 4.635 | 2.778 | 1.133 | 0 |

| Country | 1950 | 1940 | 1930 | 1920 | 1910 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 30.454 | 9.585 | 12.396 | 11.090 | 15.242 |

| Spain | 26.876 | 21.022 | 47.239 | 29.565 | 29.541 |

| Guatemala | 4.613 | 3.358 | 17.023 | 13.974 | 21.334 |

| Colombia | 0 | 0 | 273 | 182 | 82 |

Source: Instituto Nacional de Inmigración de México (INAMI), 2010.

These families are formed by citizens of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, which complicates cross-border conflicts and requires solutions that protect minors involved in agonizing family disputes.

In this context, we present a brief and informal overview regarding Mexico and Mediation (Part II); and some ideas regarding international child abduction by a parent and international family mediation between Mexico and the U.S. (Part III).

II. Mexico and mediation

Although mediation in Mexico only started recently, it has already had a notable impact on how family-related disputes are resolved. In Mexico, Alternative (or appropriate) Dispute Resolution (ADR) is grounded in the Constitution. The Mexican United States, established in Article 17 of its 1917 Constitution that “the law will consider controversy resolution mechanisms” (published June 18th 2008) (our own translation). Likewise, Article 18, paragraph six, of the Constitution states that “Alternative forms of justice should be used in the implementation of this system (the juvenile justice system), where appropriate.

In all proceedings in which an adolescent is prosecuted, due process of law and independence among the authorities that issue the referral and those that enforce the measures shall be observed. These measures should be proportional to the transgression carried out and shall aim at the adolescent’s social and family reintegration, as well as the full development of his or her person and capacities. Confinement shall only be used as an extreme measure and for the shortest possible time. Confinement can only be applied to adolescents over the age of fourteen who have committed antisocial acts deemed serious”.

Note also that:

-Mexico is a Federation organized into 31 States and a Federal District (Mexico City), each having sovereignty for diverse legal matters, including ADR; i.e., family law is local not federal. As a result, 32 Codes would normally have to be amended. This said, a bill is currently pending to amend Article 73 of the Constitution with regard to ADR, April 28th, 2016, so Congress enact a General ADR Law. This Law would be compulsory for all states, as well as the federal government.

-Under ADR statutes, Alternative Justice Centers have been established in 31 different jurisdictions, each located in the State´s Supreme Court facilities.

-In Mexico, mediation in Courts is the most widely used form.

Mexico has 31 Alternative Justice statutes (Ley de Justicia Alternativa) (with the exception of Guerrero) and 30 Alternative Justice Centers (except Guerrero and Queretaro). The 2008 Alternative Justice Act and its reforms and amendments, enacted between 2013 and 2015, are also worth noting. Although the reforms of June and August 2013 tried to make the request to mediate mandatory in Mexico City, it was never enacted, as the Alternative Justice Center was unable to deal with massive requests.1 Although mediators in Mexico City are usually attorneys, this is not a requirement under the 2013 and 2015 reforms. Most states only require that these facilitators are trained to conduct mediation proceedings.

In Mexico City, the Alternative Justice Center (AJC) offers the following types of mediation:

-2003 Family Mediation

-2006 Civil and Commerce Mediation

-2007 Restorative Justice

-2008 Juvenile Mediation

-2010 Private Mediation

-2013 Community Mediation and School Meditation (As part a sinergy project)

-2013 Mediation sessions are conducted by officers known as Secretarios Actuarios.

In Mexico City, under such circumstances, spaces have been established for both public and certified private mediation. Beyond this jurisdictional context, there is uncertified private mediation or private mediation in Mexico.

Alternative Justice Centers in Mexico City employ three types of mediators: (a) public mediators; (b) certified private mediators; and (c) uncertified mediators (or “private mediators”).

-Public mediators are public servants employed by the Alternative Justice Center in each jurisdiction;

-Certified private mediators are accredited and supervised by each corresponding Alternative Justice Center, and

-Uncertified private mediators or private mediators work on a freelance basis.

Worth noting is that settlements reached through public mediation or certified private mediation are legally binding in Mexican Courts. Settlements reached through uncertified private mediation (or “private mediation”) are not legally enforceable, unless stipulated otherwise under applicable law.

Challenges faced in Mexico in cases of international child abduction by a parent:

-“Amparo” trials can be appealed;2

-Use and abuse under the exceptions (international parental child abduction) of the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (“Hague Convention”);

-Recognition and enforcement in an international context

Though there are about 22 million inhabitants in the Mexico City metropolitan area, the Alternative Justice Center has only 24 Public Mediators, consisting of:

- 7 Civil and Commercial Mediators

- 12 Family Mediators (7 AJC plus 5 CECOFAM)

- 5 Restorative Justice or Criminal and Juvenile or Teenagers Mediators

In total, the Alternative Justice Center employs 347 Certified Private Mediators, among them 114 fully-accredited Secretarios Actuarios. Hence we highlight the reduced number of public and certified private mediators.

The Mexico City Alternative Justice Center has a series of agreements with diverse local institutions that helps promote and apply mediation in numerous fields, including INVI, INFONAVIT, LOCATEL, PGJDF, AHM, INE, etc.

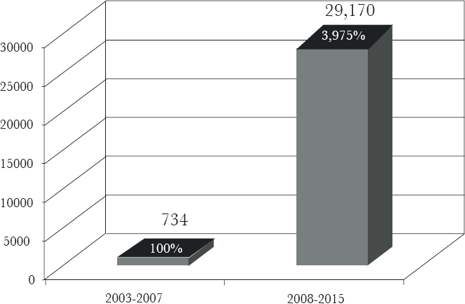

Between 2008 and 2015, the Mexico City Alternative Justice Center handled 58,512 public and certified private mediation cases. This figure represents a significant increase in the use of mediation compared with the period 2003-2007.

Source: Alternative Justice Center Mexico City.

Table 3 Cases attended by the Center for Alternative Justice of the Tribunal Superior de Justicia del Distrito Federal

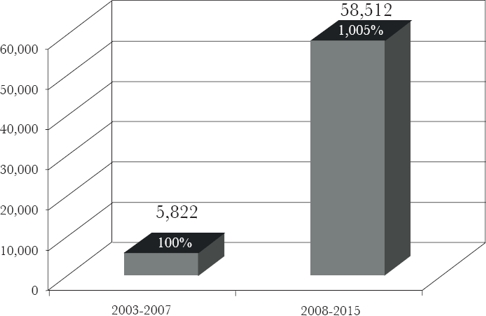

Note a significant increase in the number of agreements subscribed between 2008 and 2015, when there were 29,170 settlements:

Based on its commitment to continuing education, evaluation and high public attention, the Mexico City Alternative Justice Center scores a high Index of Qualification.

Additional information about mediators and requirements in Mexico City:

-As mentioned earlier, Mexico Cit mediators are usually attorneys but it is not a requirement (reform August, 20th 2015).

-Confidentiality. Mediators must treat anything discussed during the mediation as strictly confidential, which is considered key in building trust between the parties. Under law, mediators cannot act as witnesses in any legal proceedings related to mediation cases in which they were involved. These rules derive from both the principle of confidentiality and the duty of professional secrecy.

An exception to confidentiality applies when (a) evidence exists of a danger to the physical or mental integrity of a mediator; or (b) information exists of offences prosecuted ex-officio, which are normally serious crimes, such as homicide, robbery, arson or indecent assault. In these cases, mediators must direct the parties either to specialized institutions or, if necessary, inform the authorities.

III. Mexico - USA and Family Mediation in International Parental Child Abduction

“Love has a universal language that knows no borders…but has legal difficulties because the world has different legal systems”. This section is an overview of international parental child abduction and mediation between Mexico and the U.S., starting with a brief description of the Mexican government’s interest through its Foreign Affairs Ministry.

The notable increase in cross-border child abduction by a parent makes this topic both relevant and newsworthy. In general, this increase can be explained by:

- More cross-border family ties.

- Crisis of marriage as an institution (as well as the crisis of couples).

- More cross-border family conflicts.

- More child custody cases arising from marital dissolution.

Manipulation of children as weapons during marital breakups have given rise to more abductions and often permanent damage to minors.

This occurs when one of the parents either wrongfully removes a minor child (under 16 y.o.) from his or her normal country of residence; or retains the child in a way that breaches the other parent´s custody rights.

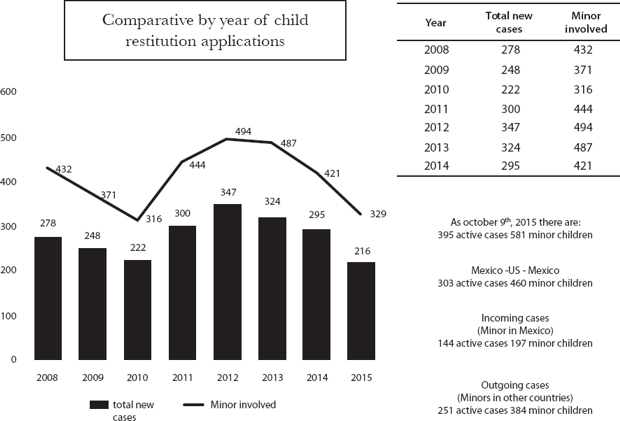

Mexico and the U.S. represent 10% of all international parental child abductions worldwide. In October 2015, Mexico had almost 400 active cases involving 581 minors. Between Mexico-USA were are 300 cases with 460 minors involved.

Worth pointing out is that case reporting requirements differ for each country; while the U.S. Central Authority includes all reported cases, Mexico only considers cases that have actually been filed with the corresponding Central Authority.

Source: http://proteccionconsular.sre.gob.mx/index.php/2013-05-23-18-19-55/89-inicio/derecho-de-familia/129-estadisticas [accessed on 12 March 2016].

Table 5

With regard to children:

-Best Interest of the Child (Article 3 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child).

-“The child´s right to maintain on a regular basis (…) personal relations and direct contacts with both parents” (Article 10 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child)

-A human right to be neither separated nor abducted by any of the parents.

The 1980 Hague Convention - signed and enforced in both countries in 1988 and 1991 - seeks to ensure the child´s prompt return to his/her habitual State of residence, that is:

-Rule: Immediate restitution of the child to his/her habitual state of residence and to restore the status quo before the abduction as quickly as possible to lessen the harmful effects of the wrongful removal or retention.

-Exception: No restitution (Articles 12, 13 and 20 the 1980 Hague Convention).

Art. 12 (2): exceptions to returning the child include the child becoming settled due to the passing of time - one year since the wrongful removal or retention;

Art. 13. (1)(a) consent or acquiescence by the applicant;

Art. 13. (1)(b) a grave risk that return will expose the child to harm; or place him/her in an intolerable situation;

Art 13. (2) objections by a mature child; and

Art. 20. Any violation of basic human rights.

Although the general principles are fairly clear, there’s a problem for exceptions to summary return, at which point the Court of the child’s current place of residence (i.e., after the abduction) decides whether to send the child back to where he or she lived prior to abduction (i.e., their habitual residence).

Right now, it often seems like the exception is the rule and the rule is the exception. This constitutes a lack of respect for the Convention’s articles, a lack of respect for the spirit of the Convention and worse, an indescribable danger for the children involved in this kind of parental conflict, with an emotional and (sometimes even) physical damage for the rest of their lives.

Some challenges among Mexico and USA due its special circumstances:

-Implement a binational mediation program for cross-border child abduction cases, especially between Mexico and the U.S for their particular characteristics.

-Analyze need for specialized mediation training in cases of cross-border child abduction (e.g., bilingual, bicultural, use of online dispute resolution “ODR”)

-Assess the need for a list of specialized government-certified mediators, as well as continuing education and evaluation

-Monitor implementation of a Central Contact Point located within the site of the Central Authorities (see The Hague Guides to Good Practice Mediation).

-Required Principles and Daily Practice with a Guide or Code of Practice

-Recognition and enforcement of voluntary cross-border child custody agreements, the ¨Achilles heal¨.3

Based on the above, we propose the implementation of a Binational Program involving Mexico and the U.S. consisting of:

-Prevention. Mediating cases to prevent future child abduction - education and persuasion; and

-International Family Mediation. International parental child abduction cases.

Binational Program

STEP ONE

STEP TWO

Budget aimed at providing access to alternative justice (human and material resources) for the sake of:

25. Process (Child’s Best Interest):Mediation Team:

Male/female;

Multidisciplinary

Bilingual;

Bicultural;

Experience and expertise in international parental child abduction cases;

Knowledgeable in different legal systems;

Links and connections - administrative and legal bodies - in order to cooperate;

Cross-border recognition and enforcement

-caucus or private sessions at the child´s habitual place of residence (prior to abduction);

-Online Dispute Resolution “ODR” (e-mail, platform4, videoconference…)

IV. Conclusions

We recognize that mediation is not a panacea and has limitations, including: nature of the conflict; specific needs of the parties; specific circumstances of the case; inability or unwillingness to meet or listen; or particular legal requirements that may impair the mediation.

We also know that mediation has several advantages which, in cases of cross-border parental child abduction, can expedite resolution; bring balance of power; reduce economic and emotional costs; bring many positive deals related to visit, travels, support, education, etc.

Definitely, we are not talking about a confrontational position between mediation and litigation. On the contrary, mediation and litigation are complementary, especially in family conflicts because it is clear to us that solutions or agreements obtained through a process as mediation are more prone to being fulfilled and longer lasting.

Settlements reached by the parties themselves tend to be more durable, flexible and longer-lasting. The stakeholders who engage in mediation often gain responsibility in implementing the best practices available, especially when a child is involved; in this way, it benefits one of the most vulnerable sectors of society.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)