Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Mexican law review

versión On-line ISSN 2448-5306versión impresa ISSN 1870-0578

Mex. law rev vol.6 no.1 Ciudad de México jul./dic. 2013

Articles

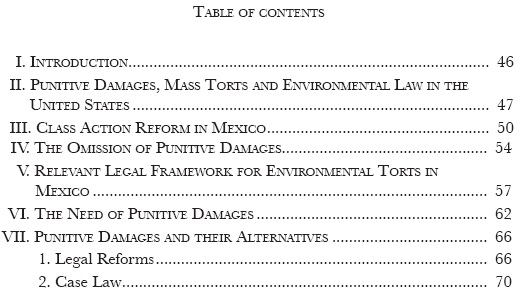

Punitive Damages and their Alternatives in Mexican Environmental Law

Rodrigo Camarena González*

Recibido: 7 de febrero de 2012.

Aceptado para su publicación: 28 de noviembre de 2012.

Abstract

This article reviews the general bases of class actions in Mexico. It also examines national legislators' decision not to include punitive damages in the current Mexican law, and places special emphasis on the global need for effective legal instruments to prevent and redress ecological disasters. Finally, this article proposes what could be the elementary basis for a legal alternative to overcome the lack of punitive damages in terms of environmental law.

Key Words: Collective actions, mass torts, punitive damages, environmental law, tort law, illegitimate enrichment.

Resumen

Este artículo analiza las bases generales de las acciones colectivas en México y en Estados Unidos. Estudia, asimismo, la decisión del legislador nacional de no incorporar los daños punitivos dentro del actual marco jurídico mexicano, y realiza un especial énfasis en la necesidad mundial de instrumentos legales eficaces para impedir desastres ecológicos. Finalmente, propone lo que podrían ser las bases elementales para encontrar una alternativa jurídica para superar la falta de dicha figura jurídica en materia de daños ambientales.

Palabras clave: Acciones colectivas, daños y perjuicios colectivos, derecho civil y ambiental mexicano, enriquecimiento ilícito.

I. Introduction

In the U.S. legal system, compensatory damages are a financial award in civil litigation, aimed at redressing the harm done to a person or private property. These "are intended to represent the closest possible financial equivalent of the loss or harm suffered by the plaintiff, to make the plaintiff whole again, to restore the plaintiff to the position the plaintiff was in before the tort occurred."1 This type of awards is the general rule in tort litigation, as in most cases these are sufficient to compensate the plaintiff for the damage caused by the responsible party.

Originally developed by British Common Law, vindictive, exemplary or punitive damages are a kind of financial award not for the purpose of acting as compensation for the plaintiff, but rather to punish the defendant for malicious conduct and whose action is beyond the scope of criminal law. Punitive damages "are an additional sum, over and above the compensation of the plaintiff, awarded in order to punish the defendant, to make an example of the defendant, and to deter the defendant and others from committing similar torts."2

As Judge Richard Posner asserts, punitive damages are a kind of civil fine that embodies the "community's abhorrence at the defendant's act."3 Hence, punitive damages are used in civil litigation when the act is exceptionally reprehensible and redress is difficult to quantify using traditional tangible standards of compensatory damages. Posner and William M. Landes argue that punitive damages are useful when there is a lack of market information that could be used to award an objective amount.4 Posner proves his point by affirming that "If you spit upon another person in anger, you inflict a real injury but one exceedingly difficult to quantify."5 Likewise, damages caused to the environment may be difficult to measure, as these are not guided by commercial parameters. It is easier to measure the damage done after a car crash than it is to measure the pollution in a lake and its consequences on human life. This last scenario is now possible in Mexico, thanks to the newly created collective actions, which allow entitled subjects to sue polluters for damages done to the environment.

With the 2011 collective actions reform in Mexico, one could think it was the proper moment to analyze the viability of this figure in order to redefine exemplary damages in the Mexican system. Nevertheless, the Congress decided not to incorporate punitive damages into Mexico's legal framework or even in matters dealing with environmental law, a branch of law in which having powerful instruments to prevent and redress damages, as well as to deter reckless respondents, are indispensable.

Throughout this essay, punitive damages, mass torts, class or collective actions and ecological law will be analyzed within the Mexican legal structure, and contrasted with U.S. legal framework, without losing sight of the global need for unambiguous instruments to avoid pollution and toxic disasters while reprimanding those responsible for these damages.

II. Punitive Damages, Mass Torts and Environmental Law in the United States

Some modern precedents of punitive damages may be found in Day v. Woodworth6 and in Jones v. Kelly,7 which expressed the implied duty of not to harm others, and the concomitant legal possibility to penalize malicious acts in civil adjudication. This implied legal protection independent of any printed document was expanded in Comunale v. Traders.8 Other landmark decisions have arisen from the California high court, such as Crisci v. Security,9 Gruenberg v. Aetna,10 Ins. Co, and Richardson v. Employers Liab,11 which laid down that even in contractual relations there is an implied covenant of good faith imposed by law. A breach in these cases arises from nonconsensual sources. Hence, when an enterprise acts in bad faith, this act is translated into a tort, a financial obligation intended to reprimand the responsible.

Unlike compensatory damages, punitive damages are an additional sum payable by the respondent. This action seeks to punish an improper act and discourage similar attitudes, rather than to restore things the way they were before the act. Consequently, these torts are aimed at decreasing social inequality between citizens and entities.

The common law doctrine of torts is complemented with the statutory provisions from some states of the Union, like that in the Civil Code of the State of California, section 3281 of which defines the general concept of damages, as well as the duty to repair damages. In addition, section 3294 provides a definition of exemplary damages: "In an action for the breach of an obligation not arising from contract, where it is proven by clear and convincing evidence that the defendant has been guilty of oppression, fraud, or malice, the plaintiff, in addition to the actual damages, may recover damages for the sake of example and by way of punishing the defendant."

These damages are treated differently depending on the state and are generally awarded, at least in first instance, by a citizen jury. This characteristic of civil procedure can lead to excessive awards.

One case that contributed to the unfavorable perception of this type of lawsuits was Liebeck v. McDonald's Restaurants,12 a lawsuit regarding third-degree burns caused by an involuntary spill of the fast food chain's coffee on a 79-year-old woman that ended in an out-of-court settlement in favor of the wounded woman for about $600,000 USD. Similar cases may have contributed to the association of punitive damages with frivolous litigation or excessive lawsuits. However, without analyzing the controversy behind punitive damages in strictly commercial relations, we should point out that punitive damages may be required in some cases to satisfy basic elements of justice and prevent malicious actions committed by powerful entities, such as transnational companies.

Damages in the United States may be claimed either individually or by a single mass tort lawsuit signed by a collective through class or collective actions. Mass torts can also be claimed through a joinder of several distinct cases filed by different individuals against the same respondent and caused by the same act, but whose damages must be determined individually. Mass torts usually deal with environmental disasters (such as mass toxic torts or mass disaster torts) or products that have injured several plaintiffs (product liability torts).

One example of a mass torts case is that of Exxon v. Baker.13 In 1989, an Exxon supertanker ran aground on a reef in Alaska, and spilled millions of gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound. Hence, several civil cases, including the one brought forward by Grant Baker, were consolidated to claim compensatory and punitive damages since the plaintiffs depended on Prince William Sound for their livelihood. In first instance, the jury ruled that Exxon was to pay 5 billion USD in punitive damages. In the appeal, these were reduced to 2.5 billion USD. In the end, the United States Supreme Court (USSC) revoked the second instance ruling and determined that in maritime tort cases, the amount awarded for punitive damages should not be higher than that for compensatory damages. In view of this 1:1 ratio between punitive and compensatory, the latter were reduced to $505.7 million USD.

One instance of the necessity of punitive damages is the 1984 Bhopal disaster in India. In consequence of poor planning, negligence and misinformation, a toxic gas leak at a Union Carbide plant caused the death of around 20,000 people and exposed almost 200,000 people to a fatal gas.14

Immediately after the tragedy, civil legal actions in the United States were filed against Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) and Union Carbide. However, under the forum non conveniens doctrine, the respondents argued that the Indian Supreme Court was the proper forum in which the case should be handled. This motion to dismiss was considered appropriate; thus, litigation was transferred to the Government of India, whose domestic law system did not award, at least at that time, punitive damages.15 The legal quarrel began with a $3 billion USD claim, an amount that given the human and environmental costs of the calamity seemed reasonable. Nevertheless, UCIL rejected all legal responsibility regarding victims' health and reached a settlement with the Government of India for only $470 million USD.16

On the one hand, it is not unreasonable to say that the settlement could have represented a more onerous financial obligation if UCIL was liable not only for compensatory, but also punitive damages. The possibility of obtaining punitive was conceivable under U.S. tort law since that 50.9% of UCIL's stock was owned by Union Carbide, a New York City corporation.17

On the other hand, the ratio decidendi in the U.S. court decision is also logical as most of the evidence was in India and it would, therefore, be much more practical to hold the procedure there.

This dilemma between punitive damages in the United States and procedural difficulties might well have been overcome through the use of exemplary damages in India. Punitive damages are useful legal instruments, which together with the class and collective actions lawsuits, should be employed to seek compensation and punishment for negligent accidents, injuries caused by medicines and toxic damage.18 If Indian jurisprudence had recognized punitive damages before the trial, the victims could have received a more satisfactory response; although it is likely that UC's litigation strategy would have been different.

In addition to tort law, administrative law implemented by state agencies and citizen lawsuits play an important role in the enforcement of U.S. environmental law. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is a federal state agency whose main functions are to regulate standards of environmental law, monitor compliance with environmental laws and regulations and sanction infringements of said laws.

Administrative law enforcement is complemented by "citizen suits", which proceed once the alleged violation has been notified to state administrators.19 If said infringement continues, any citizen is entitled to initiating civil actions at district courts against any person who violates environmental law standards set forth in the Clean Water Act or the Endangered Species Acts, among other statutory provisions. It is not necessary for the suit to be filed by a group of persons; even a single individual is entitled to bring environmental civil action against any individual or entity that ignores environmental regulations. It is even possible to sue the EPA Administrator for omissions or passive acts. The function of the EPA is similar that performed by certain Mexican agencies, like SEMARNAT (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources) and PROFEPA (Federal Bureau of Environmental Protection). To a certain extent, U.S. citizen suits have some points in common with Mexican legal institutions as the denuncia popular (collective claim available at administrative environmental law), and with the now available diffuse action (accessible through federal litigation).

III. Class Action Reform in Mexico

On August 30, 2011, pursuant to the constitutional amendment of Article 17 of the Federal Constitution of Mexico, the Mexican President published the statutory reform of substantive and procedural law which now regulates collective actions. The legislative act consisted of the formal amendment of seven statutes, including the Federal Civil Code (FCC) and the Federal Code of Civil Procedure (FCCP). These legislative measures were expressively aimed at limiting the use of representative actions only for matters of consumer relations or environmental law.20 The federal amendment changed over 50 articles in federal civil procedural rules, and six other federal acts, including the organic law of federal judicial system, which now authorizes Civil District Courts to hear collective actions.

The Mexican Federal Congress (MFC) classified class lawsuits into three categories: diffuse actions, collective actions in the strict sense, and individual homogeneous actions.

The first type of action is designed for collective rights with an undetermined entitled party. Collective action (in the strict sense) is the appropriate action to protect the aims of a particular group of people. Individual homogeneous action is used for contractual individual interests connected by common circumstances that have been affected by a third party. All collective actions (in broad sense) are only available for citizens when 30 people or more sign the lawsuit.

The MFC emulated some elements of Rule 23 of the U.S. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,21 such as the need of class action certification, the burden for the plaintiffs to prove the appropriateness of the collective action instead of individual litigation, and the notification to potential class members.

Perhaps, it would be more accurate to talk about the Mexican collective, rather than class actions, since legislators followed the "opt-in" model of U.S. collective actions, rather than the "opt-out" of class actions. This is the model provided by U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The opt-in procedure means that whenever a collective action is filed, potential plaintiffs must be notified, and it is their decision whether to give their consent to adhere to the suit and its legal consequences.22 Conversely, in class actions following the opt-out model, the general rule is that all potential members of the class are included in the process, thus the judgment would bind all members unless they express their intention to opt-out.23

The "opt-in" model was implemented by MFC, and is now expressly provided in Article 594 of the FCCP. Potential members of the collective have up to 18 months after the judgment is issued, or the out-of-court settlement is reached, to adhere to the lawsuit and be bound by its outcome.

Other new developments of the reform are the admission of amicus curiae briefs, the courts' ability to issue positive preliminary injunctions or interim measures,24 the reinterpretation of standing requirement which allows civil associations to intervene in collective actions, the presence of experts at the judges' discretion and most importantly, the creation of a national judiciary fund to handle the financial resources derived from diffuse actions in cases of economic fulfillment of the judgments.

According to Article 585 of the FCCP, any group of thirty persons, the Attorney General, non-profit associations whose purpose is to protect the environment or to claim consumer rights violations and four other specialized state agencies have the standing required to sue collective actions at federal civil courts. The amendment is so relevant that a completely new part was added to the FCCP.

Damages that harm the environment in general in such a way that it is impossible to determine a specific number of aggrieved individuals is claimed by filing a diffuse class action, which is now defined by Article 581 I of the FCCP as follows:

I. Diffuse action: Is one of an indivisible nature that is exercised to protect the rights and diffuse interests of an undetermined collective, for the purpose of legally suing the respondent to redress the damage caused to the collective, consisting of the restoration of things to the state as they were before the harm done, or otherwise claim alternative compliance with the judgment according to the impact had on the rights or interests of the collective, without the need of any contractual link whatsoever between that collective and the respondent.

Sections II and III of Article 581 define the two other types of collective actions thus:

II. Collective action in the strict sense: is one of an indivisible nature that is exercised to protect the collective rights and interests, held by a specific collective or determinable based on common circumstances, which aims to legally sue the respondent, to repair the damage caused, consisting of carrying out one or more actions or refraining from doing so, as well as covering damages to individual members of the group derived from a common legal relationship mandated by law between the collective and the respondent.

III. Homogeneous individual action: is one of a divisible nature, that is exercised to safeguard individual rights and interests of harm with a collective impact, whose holders are individuals that are grouped based on common circumstances, which aims to legally sue a third party for the mandatory compliance of a contract or its termination with the consequences and effects under applicable law.25

Environmental collective actions can be filed either by a group of thirty individuals, non-lucrative associations, or by public agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Environmental Protection (PROFEPA), a federal agency under the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT). Together, both agencies perform similar functions to those executed by the U.S. EPA, although the U.S. agency does not have legal standing for environmental class actions, but rather protects the environment through administrative procedures.

Unlike the more in-depth modifications made to the Federal Code of Civil Procedure, environmental statutes were not equally transformed. Only two reforms were made to Article 202 of General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection regarding PROFEPA's powers to initiate lawsuits. one of said modifications consisted of adding the possibility of collective actions claimed by either the PROFEPA or any other subject with legal standing by the addition of a second paragraph. The addition of a new third paragraph of said article now places environmental collective actions exclusively under federal jurisdiction, even if the violations apparently arise from state environmental law.

These reforms have created the possibility for a state agency, which usually acts as an authority in administrative law, to be transformed into an entity that represents and claims civil damages caused to the environment. Lawsuits of this nature would take the place of or have equal rank as private law proceedings and be decided by a civil district judge, who will also analyze administrative infractions, i.e. public environmental law based on legal ties between authorities and citizens in a vertical legal relationship.

This public-private transformation of collective action lawsuits already has an interesting precedent ruled by the First Chamber of the Mexican Supreme Court (SCJN). In PROFECO v. CTU,26 the Chamber analyzed two Amparos derived from a collective action filed by the Federal Agency of Consumer Rights (PROFECO) against a construction company whose actions caused harm to at least 82 consumers, who complained to the PROFECO office in the State of Chihuahua. In this homogenous individual action case, the SCJN then recognized that the PROFECO was the only entity empowered to initiate collective actions regarding consumer rights violations.

In Amparo 14/2009, the Chamber highlighted the elements of this collective action procedure which included that: (a) mass torts, regardless of the legal relationship from which they arose, are a civil law institution; (b) the PROFECO's has the authority to claim consumer right violations in detriment of a collective; (c) it is necessary to demonstrate harmful conduct, without having to identify all of those affected; and (d) the objective of a judgment is to declare that collective harm has been caused by the defendant and that this tort must be redressed.27

Furthermore, in Amparo 15/2009, the Chamber recognized the need to guarantee collective rights and that the effects of the judgment must be ultra partes, i.e. the sentence must protect all of those affected, and not only those who complained before the PROFECO. This was established to achieve a comprehensive restitution of the violated collective right.28 Nevertheless, this judicial interpretation has now been overcome by the "opt-in" model provided for in statutory provisions.

Hence, in collective action lawsuits filed by state agencies or other plaintiffs, the agency becomes a sort of Ombudsman while the federal judiciary acquires full jurisdiction over consumer rights and now over environmental law. Thus, judges are empowered to issue collective judgments to protect collective and diffuse rights.

IV. The Omission of Punitive Damages

The collective action reform was a historic opportunity to revitalize civil litigation according to international commercial relations and inherent Mexican needs. Nonetheless, the reform on its own may not be enough to satisfy national needs, especially that of social inequality between the parties in litigation.

Some of the measures taken by the MFC may be an obstacle for citizens to attain effective judicial protection. These include the difficulty of issuing judgments in diffuse actions;29 the loophole regarding alternative compliance with the ruling, the ratio or way to measure damages in environmental actions; and especially, the exclusion of punitive damages.

An important position regarding collective actions and exemplary damages in Mexico is that of Jorge Gaxiola Moralia, former dean of the "Escuela Libre de Derecho" Law School in Mexico City. Gaxiola's opinions on punitive damages were expressed on April 7, 2010, in a paper presented at the Collective Actions Forum on State Policy Reforms from an Environmental Perspective at the Chamber of Deputies. He was concerned about the negative influence of class actions on the market, as enterprises transferred the cost of said damages to the consumer.30 He expressed his fears of citizens' abuse of representative actions lawsuits in detriment of enterprises, such as claims for excessive compensations; the instability the threat of class actions can have on shareholders, owners and employees; unfair out-of-court settlements, and so on. Finally, he stated that "there should be no punitive damages."31 According to Gaxiola, these damages are measured not by the harm done, but by the size of the enterprise. Thus, plaintiffs may use punitive damages to unfairly threaten companies. Moreover, he believed that exemplary damages are only measured according to the size or economic prosperity of the responsible party, and in extreme cases, relatively minor damage could mean the bankruptcy of an innocent enterprise.32

This portrayal of punitive damages may be true in some cases, but it is not entirely accurate since there are numerous restrictions both for claiming punitive damages and for measuring these. Thus, Section 3294 of the California Civil Code requires determined malicious acts to have "clear and convincing" proof and that "no claim for exemplary damages shall state an amount or amounts."

Some torts regulations, such as those in the State of Georgia, provide that vindictive damages may be awarded, and call for an "entire want of care which would raise the presumption of conscious indifference to consequences."33 Furthermore, the cited law orders that 75% of the punitive damages must be paid to the state coffers, making such lawsuits instruments to protect the collective, instead of malicious threats guided by individual greed against blameless companies. Similar models of split of punitive damages between the plaintiff and the state are followed in other nine U.S. states.34 Other statutes prevent juries from awarding excessive punitive damages by limiting the frequency and setting a maximum permissible amount. Colorado state law, for instance, provides that the amount of punitive damages should not be higher than compensatory damages, and can only be awarded in cases of "fraud, malice, or willful and wanton conduct."35

Other aspects of punitive damages worth considering are that they may be necessary when the harm is difficult to measure or when the damage done cannot be appropriately redressed by criminal law. Diffuse actions on environmental issues seem to coincide with these two possibilities since judges may lack objective evidence to award damages that fully compensate a diffuse collective for a harm done to natural resources that are not available on the market. Moreover, administrative and criminal fines are limited by abstract upper limits which may be insufficient to punish the polluter and deter others from committing similar actions. For example, criminal fines for damages to the environment are limited to 3000 days of minimum wage; these are around $180,000 Mexican pesos or $14,000 USD. These fines can be increased up to 4000 days or approximately $240,000 Mexican pesos or $18,000 USD,36 an amount that may be inadequate to reprimand the defendant in cases of gross negligence or wanton disregard.

Just as collective actions were adapted according to the context of Mexico, vindictive damages could have likewise been transformed into a deterrent for irresponsible entities without affecting the legal certainty and welfare of enterprises and employees. However, legislative reform has not yet addressed this adjustment.

The MFC adapted representative actions by granting exclusive federal jurisdiction and limiting the abuse of lawsuits and frivolous litigation. Even though Mexican Constitution states that all citizens have the obligation to act as members of a jury, both criminal and civil trials are brought directly before a judge, and a jury never issues a verdict. Hence, in Mexico, there is no possibility of juries awarding inflated damages that will later be lowered or declared unconstitutional by higher courts. Additionally, mass torts are regulated restrained by a single civil code, and only federal courts are empowered to handle this kind of action. This sole regulation and jurisdiction implies that there is only one type of case-law regarding mass torts, which will in turn make it more practical and predictable for the parties involved.

If all these circumstances were redefined in the Mexican legal system, and given the need of punishment and prevention of natural disasters and pollution, it would not be for Mexican legal scholars and congressmen to create an institution to function as a civil penalty. This is particularly important in cases of diffuse actions in which plaintiffs can act on behalf of the community and the environment in a subordinated substantive de facto relationship between powerful corporations and weak individuals, or even voiceless entities.

The amended Article 625 of the FCCP may still resemble split-recovery statutes like the one enacted in Georgia. Article 625 provides for the creation of a fund made up of the financial awards in diffuse actions to be managed by the federal judiciary. These resources must be used to pay court costs and the fees of plaintiffs' representatives while the rest should be invested in research and the dissemination of collective rights. Hence, a portion of the damages is distributed in favor of the plaintiff to recover the expenses initially assumed and the rest is distributed publicly through the promotion of diffuse actions. Thus, there is no lucrative incentive for plaintiffs that could be used to pressure innocent responsible parties. This would in fact contradict the diffuse nature of the action and the non-profit role of most of the entitled entities. Even then, fines and compensatory damages may be insufficient to punish the defendant and redress mass and diffuse environmental torts.

One alternative would be to reform civil and environmental statutes to allow for an extra fine during the collective action procedure when it is a case of gross negligence or wanton disregard on the part of the defendant and when administrative and criminal fines are not proportional to the damage done. The extra amount could deter similar cases in the future without turning collective actions into speculative litigation and the resources could be managed as part of the judiciary fund. Another option for implementing punitive damages or similar disincentive instruments in the Mexican system would be for the plaintiffs of collective actions to claim an additional amount under the concept of moral damage or illicit enrichment. These possibilities are discussed below.

V. Relevant Legal Framework for Environmental Torts in Mexico

The FCC establishes the obligation of not harming others, as well as different non-contractual theories for one individual to claim damages from by one particular against another. These causes of action refer to objective or subjective liability, as well as moral damage.

According to Article 1913, civil objective liability is caused by objects which are dangerous in themselves, regardless of whether or not there was an element of fault or negligence. Thus, the owner responds to the victim to repair the damage caused by the object. Conversely, Article 1910 is the basis for civil subjective liability, in which the notion of culpability and remissness is essential.

Furthermore, Article 1916 of the cited statute provides independent compensation known as moral damage, which is defined as:

Moral damage is understood as a harm a person suffers in his or her feelings, affections, beliefs, propriety, honor, reputation, private life, milieu and physical appearance, or how that person is perceived by others. It is presumed that there was moral damage when a person's freedom or psychological integrity is illegitimately harmed or diminished.37

Moral damage is more abstract and subjective than the other two kinds of torts. It is also complicated to determine a fair amount that could repair the harm caused. In fact, the fourth paragraph of the mentioned article requires that the compensation "must consider the injured rights, the degree of responsibility, the financial situation of the person responsible and of the victim, as well as other circumstances of the case."

Moral damages have some points in common with punitive damages. Moral damages demand an autonomous compensation regarding the rights of personality, a civil law concept that involves emotional aspects. This intangible aspect makes it very difficult to calculate a specific amount. In fact, both punitive and moral damages take into account the degree of responsibility and the defendant's wealth as parameter to award extra damages for incorporeal torts caused to the plaintiffs.

In addition to tangible damages, moral damages can be claimed in collective actions and therefore have a similar function to punitive damages. Its implementation can be useful to redress intangible damages and to deter similar acts carried out by the responsible party or others.

Regarding diffuse actions, once the defendant is convicted and it is proven that such party cannot redress its action the judge must order an alternative to fulfill the judgment by awarding damages that will be managed by the fund. Once the stage of alternative fulfillment has been completed, it would be interesting to claim the concept of diffuse moral damage. Ultimately, moral damage is found under the category of damages, and in cases of environmental harms, there can be an injury to intangible rights. The important issue would be to prove a causal link between the defendant's actions and the harm caused to the intangible rights of the collective.

As to collective actions in the strict sense and individual homogeneous actions, Article 605 provides that the court ruling may simultaneously order the responsible party to carry out of an action, refrain from doing an action, and pay damages in favor of the collective.

Thus, it would be a matter of court's interpretation to ascertain whether the claim of moral damage is consistent with the collective action reform or if it designed just to protect corporeal rights. If the judiciary opts for a broad interpretation, moral damage may well perform a more or less similar function to that of punitive damages without the need for statutory reform. In cases of diffuse actions, moral damages would be managed by the fund, while in the other two scenarios, these would be awarded to the plaintiffs.

Diffuse actions embody a new kind of procedural relation at civil litigation. Before the collective actions reform, civil adjudication referred to a relationship between two or more concrete legal subjects. This controversy could arise between individuals, corporations or state agencies defending their particular interests. Nowadays, an environmental diffuse action lawsuit is triggered by a group of individuals or a non-profit entity that has legitimatio ad processum, acting as the plaintiffs that represent a diffuse collective, an entitled body with locus standi or legitimatio ad causam. Therefore, it is no longer traditional litigation since the rights of a diffuse collective are being claimed instead of those of specific individuals as normally regulated by civil law.

Besides, determining an amount of damages in environmental diffuse litigation is more complicated than in similar civil cases since the ruling will not only aim at redressing a conventional dispute between individuals, but also between the ecosystem and its polluters. The environmental harm represents a hybrid of civil and administrative law and meeting the individual's and society's demands can be solved through a civil fine.

In view of the peculiarities of environmental damage, the addition of a single article in the Federal Civil Code looks incomplete,38 a loophole which can be overcome through federal case law.

Another alternative for environmental exemplary damages is the possibility that not only could all the subjects with standing claim compensation through traditional damages, but also that the plaintiffs could sue the responsible parties for illegitimate enrichment. Article 1882 of the FCC dictates "Whoever becomes enriched at the expense of another shall indemnify that person for his or her impoverishment to the extent in which he has been enriched."

Article 1882 implies that if one individual is enriched at the expense of the environment, any illicit revenue must be nullified since it was outside the scope of the Rule of Law, and the collective and the environment are affected by these damages.

The penalty for illicit enrichment is to give, not the obligation to act. Thus might not order an action be aimed to restore the things they were before the act committed. This redress is only achieved through actions and not through monetary fines, which are obligations to give. Once it is proven that it is impossible to redress the damage through actions, the legal remedy is achieved by awarding damages. However, a restrictive interpretation of Articles 604 and 605 may deem illicit enrichment not as a kind of damages, but rather as an independent source of obligations, not claimable in collective actions procedures. Hence, one interpretation could be that illicit enrichment cannot be claimed through collective actions, but only damages.

Another reading can be arisen from Articles 5 and 70 of the FCCP which orders that all the issues surrounding controversies must be discussed at one trial. Thus, plaintiffs at collective actions could argue that illicit enrichment is an issue that must be discussed in the same procedure because it is closely related to the facts of the case since such profits could not have been generated but for the systematic carelessness or indifference of the respondents in detriment of the collective. A contrary interpretation may allow responsible party to keep the revenues even if these were a direct consequence of an illicit action.

Our Constitution (MC) is the Supreme Law of the land. Below it, there statutes, regulations and federal standards issued by administrative agencies like the SEMARNAT. Codified law is supplemented with case law, which is almost monopolized by the federal judiciary since most court decisions are reviewed by federal courts through the constitutional remedy of Amparo.

Through the Amparo, a vast number of the constitutional duties performed by any act by an authority are subject to review by constitutional courts, provided it is a state agency involved and functioning as such, in a vertical legal relationship. Administrative law is also a branch of the legal system that deals with vertical relationships enforceable by government agencies, but is determined by legal instruments rather than constitutional ones, and only as an exception are administrative acts directly reviewable through the Amparo.39 Conversely, as a general rule, horizontal legal relationships, i.e. between particulars, are limited by infra-constitutional sources, such as federal acts and codes.

Article 4, fifth paragraph of MC gives all inhabitants the basic right to a healthy environment, and as of February 8, 2012, this article also recognizes the accountability of all persons who harm the environment. If any state agency violates this right, the corresponding claim would be enforceable through an Amparo in federal courts to restore the constitutional damage claimed by the aggrieved. In short, the intervention of an authority is needed to analyze any potential infringement of fundamental rights, a principle of jurisprudence similar to the State Action doctrine.40

The concept of justiciability is important for claiming constitutional prerogatives, including social and diffuse rights. The right to effective legal protection is provided in first two paragraphs of Article 17 of MC, which imply that any injury must be redressed once it is proven. Hence, prior to the reform, the only legal entity entitled to set the courts in motion for torts against the environment was the PROFEPA.

In the third paragraph of said Article 17 also forced the MFC to develop mechanisms to redress damages that arise from class actions. However, the legislative measures taken seem inadequate as it is not clear how environmental damages are to be quantified and repaired by federal courts. Additionally, the sixth paragraph of the same article establishes the obligation all legislatures have to ensure the exhaustive execution of judgments. This implies that the right to a healthy environment must be restored by the condemned party pursuant to the rulings on collective actions, and in the case that it is physically impossible to restore the damage done, the federal government must guarantee that the respondent has been fairly punished and that similar disasters do not happen again.

Along the same lines, the sixth paragraph of Article 25 and third paragraph of Article 27 of MC state that the national economy must be guided by environmental conservation. Thus, punitive damages may be used as a foil to stop abuses by companies that enrich themselves at the expense of processes that neglect the environment. Furthermore, sections XVI and XXIX-G of Article 73 empower the MFC to legislate on general health matters and the preservation and restoration of the environment. This last power shared with state and municipal governments and is regulated by the General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection (GLEBEP).

Until the class actions reform, the environmental law and its enforcement was monopolized by state agencies through either a coercive economic procedure to monitor and inspect potential polluters or an Amparo if it was a public act to the detriment of an individual. Hence, the access for citizens or non-profit entities to fight against ecological abuses was limited to filing a complaint before the corresponding authority.

At the present, there is the constitutional responsibility of providing all the legal devices to penalize, restore and prevent future wrongful acts in detriment of the environment. It is a commitment already assumed by the three branches of government: the legislature established the basic guidelines for collective actions, the executive will do its part through the SEMARNAT and the PROFEPA either as administrative agencies or plaintiffs in collective actions, and the judiciary will complete this work in favor of diffuse rights.

The GLEBEP establishes the concurrent obligation of all the branches of government at all levels and of citizens to respect the right to a healthy environment. Article 15 sets the general bases of an environmental policy that must be followed by the Federal Executive. Among other aspects, Section I of the GLEBEP states that ecosystems are public heritage and Section III provides that the protection of the environment is the responsibility of both authorities and individuals. Moreover, Section IV states that:

Whoever does any work or activities that affect or may affect the environment is required to prevent, minimize or repair the damage caused, and to bear the costs that this involvement entails. Likewise, whoever protects the environment promotes or carries out actions to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change makes use of natural resources in a sustainable manner should be encouraged to do so.

Moreover, the law determines that accountability does not only respond to current conditions, but also those that affect the quality of life of future generations; that prevention is the most effective means and that natural resources should be used so as to prevent their depletion and adverse ecological effects.41

Article 171 establishes the possible sanctions to environmental infractions in which contaminants may be liable to a fine of fifty thousand days of minimum wages, i.e. around three million Mexican pesos, which can be doubled in cases of repeat offenders. These amounts may too low to punish or redress ecological catastrophes the likes of Bhopal or Chernobyl, a situation in Mexico, which may use punitive damages as an extraordinary sanction. At the same time, Article 153 section VIII provides that in cases involving hazardous materials in particular are liable to pay for damages in addition to administrative sanctions.

The above statutory provisions imply that Mexican environmental law pursues at least three different goals: to prevent, to restore and to deter damages to the ecosystem. Thus, a fine or penalization is aimed at sanctioning the defendant and giving an example to society, unlike common damages, which are addressed at repairing the harm done.

Violations of administrative ecological law are already punishable under current state law. State agencies are responsible for enforcing environmental law, an act of authority in the field of administrative law which occurs regardless of the harm caused to the collective. The main purpose of administrative fines is to punish and avoid imminent similar harms, but not to repair the damage.

The SEMARNAT is the federal agency whose main functions are to protect natural resources, to develop and implement national environmental policy, as well as to establish environmental quality standards. Within the organization of the SEMARNAT, there is the PROFEPA, an entity which according to the ministry bylaws,42 is one of its specialized or decentralized GLEBEP agencies whose main functions are to monitor, evaluate and punish violations of environmental law, as well as to initiate legal actions against criminal or administrative law infringements.43

Moreover, Article 189 of the GLEBEP establishes a procedure for public complaint, a legal figure through which any individual can file claims against any actual or possible damage to the environment. This can result in originating an administrative procedure against the apparent offender, and can also end in a non-binding recommendation if the lawbreaker is an authority or in a binding resolution if the subject is an individual.

What, then, could be the usefulness of environmental class actions? For the sake of judicial economy, it would be to use a single action to analyze administrative and civil damages, whose effects fall onto a collective, and must be claimed in a collective action lawsuit. Therefore, both legal institutions, sanction and compensation, already coexist in conventional ecological law, i.e. the environmental rules regulated by administrative law dealing with legal relations between state agencies and individuals or civil law entities. In the administrative procedure conducted by the SEMARNAT, one state agency may impose an administrative fine as punishment for the defendant in the process in the name of the entire nation, in view of the agency's status as higher legal body. Damages may also be claimed to restore the injury caused to certain individuals or a diffuse group of people.

VI. The Need of Punitive Damages

Collective actions are useful procedural figures that make judicial protection accessible to disadvantaged social groups or voiceless entities like the environment and future generations, whose legal representation or standing had been an obstacle in enforcing collective and diffuse rights. These requirements for this legal instrument may be complemented by punitive damages used as administrative fines. Meanwhile, civil damages may be insufficient to repair ecological damages and guarantee the non-recurrence of the offender or the non-repetition of similar acts by another entity.

When a violation of ecological law is as serious as the Bhopal or Exxon Valdes cases, it is essential to calculate a legal figure that can cover the civil and administrative damages in a civil procedure, but to also perform the administrative function of deterring and preventing similar catastrophes.

Alternative compliance of judgments in environmental diffuse actions or in collective environmental actions rising from environmental damages is a sui generis procedure, which must be dealt with differently than that designed for traditional civil damages.

There are several particularities which differentiate this diffuse legal relationship from others:

a) The standing of the PROFEPA, non-profit associations and citizens is a legal fiction resulting from the need to give a voice to the environment, an entity from which we all receive benefits but which also lacks legal personality. This fiction does not represent a concrete subject, nor is it an authority or an individual; it is a diffuse entity that represents the entire community;

b) Environmental damages represent the convergence of two kinds of damages: a civil tort that must be redressed, and an administrative infraction which must be punished;

c) Potential polluters can be companies with de facto political power. This is an obstacle for plaintiffs to confront the companies directly by means of conventional civil law remedies;

d) Traditional compensation of civil damages is not sufficient to discourage similar environmental damages; hence companies are probably not afraid of acting maliciously;

e) Environmental damages are a much more sensitive aspect of law; the quantification of this kind of damage is far more complex since ecological injures are frequently irreparable, and their consequences can be difficult to predict and measure.

The challenge of quantification has yet to be solved by federal legislators, especially in view of their enacting unclear guidelines for diffuse actions judgments. Article 604 of FCCP provides that:

Article 604. In diffuse action, the judge may order the defendant to repair the damage caused to the collective, consisting of the restitution of the things as they were before the harm was done, if possible. This restitution may include performing one or more actions or abstaining from doing a given action.

If the above is not possible, the judge shall order an alternative compliance according to the effects on the rights or interests of the collective. Where appropriate, the resulting amount will be allocated to the Fund referred to in Chapter XI of this Title.

The cited provision orders responsible parties first, to restore the damages done by establishing an obligation to take action. In case it is materially impossible to repair said damages, the responsible parties must award damages in favor of the community. However, this provision does not offer any guideline on how the damages will be determined, and nor is this parameter established in Chapter XI of the FCCP which defines the nature of the national fund.

This legal uncertainty may be overcome by developing federal jurisprudence through alternative compliance to the court's ruling, which could consider compensatory and moral damages, as well as illegitimate enrichment.

Mexico has a strong trade relationship with Canada and the United States, a relation which has led to the ratification of important agreements like NAFTA. This agreement, together with globalization and the restructuring of the Mexican system to a neoliberal economy, has strengthened market relations among the three countries. Canada and the United States both recognize punitive damages, but this is not the case of Mexico. This absence of exemplary damages may put Mexican firms and society in a situation of inequality. For instance, a Mexican enterprise with presence and assets in the United States could be liable for punitive damages; conversely a Canadian company may cause an ecological disaster in Mexico without being held accountable for any punitive damages.

The forum non conveniens doctrine of common law nations, along with the current Mexican legal framework, make it likely that in the event of an environmental disaster on Mexican territory, the forum chosen will be the place where the acts were committed. The omission of punitive damages and the concurrent disadvantage that this represents to Mexico are more tangible when taking into account the relevant provisions of the "North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation" (NAAEC), which includes the right of citizens to sue for damages.44 This right would be exercised differently under Mexican law, since a same act would be punishable differently depending on the place where it occurred, despite the implicit context of equality in which NAFTA and NAEEC were drafted.

Therefore, it is a matter of domestic law to implement legal instruments that are similar to the ones developed in the other two countries. This implementation must be constructed according to the characteristics of Mexican legal system, and aware of the nation's ecological needs, without losing sight of the fact that the main goal is for transnational corporations to respect the law of each country equally, and thus, they must legally respond in the same way.

Another example for the need of legal measures to enforce environmental regulations and guarantee the reparation of damages is the Lago Agrio case in Ecuador. In 1964, Texaco Petroleum Company (TexPet) began extracting oil in Lago Agrio, in the Sucumbios and Orellana provinces. TexPet drilled hundreds of wells and built alongside hundreds of open toxic waste pits, an irregular measure attributed as the cause of massive pollution and cancer. TexPet, together with the national oil company, now Petroecuador, formed an oil consortium. But in 1990, Texaco left the premises and the oil extraction in the hands of Petroecuador. In 1993, the inhabitants of Sucumbio filed suit against TexPet for the devastating consequences of dumping toxic waste throughout the area without proper control measures. According to El Pais, five indigenous communities used to live in the area; now two of them the Tetetes and the Sansahuaris are gone forever.45

In 1993, a class action lawsuit in the name of Ecuadorians was filed against Texaco in a New York court. However, in 2002, after the respondent argued the forum non con conveniens doctrine in view of the fact that the act had taken place in Lago Agrio, it was ruled that the proper forum to litigate was in Ecuador. In 1995, Texaco agreed to settle out of court with Ecuador and Petroecuador for 40 million dollars to clean Lago Agrio.46 However, Ecuador does not recognize this settlement as an official government declaration or State action in the name of all Ecuadorians;47 otherwise, this would be an obstacle for the locus standi of the current Ecuadorian plaintiffs.

As Texaco was purchased in 2001 by Chevron, a new lawsuit against the latter was presented in Ecuador in 2003. In 2011, an Ecuadorian court ruled against the responsible parties and ordered Chevron to pay more than eight billion dollars in punitive damages.

Chevron sought a preliminary injunction against the Ecuadorian ruling in the United States, arguing that the entire procedure was biased48 and therefore the judgment could not be enforceable in the United States, an argument that was upheld by a district judge, but later annulled by the Second Circuit Appeal Court.49

Last January 2012 in Ecuador, the court ruling against Chevron in the Lago Agrio Case was upheld in the appeal, and Chevron was ordered to pay 8.5 billion dollars, a sum that could double if the respondent refuses to offer a public apology and comply with the judgment.

The company sought for the ruling to be vacated by arguing that Chevron has no registered office in Ecuador and has never operated there, as well as that there has been a denial of justice and therefore the entire trial should be declared void. On appeal, the Court of Sucumbios applied the corporate veil doctrine and concluded that Chevron Corporation is liable for Texaco's actions in Ecuador.

The court upheld the judgment and asserted that there was a popular action granted to any individual in cases of contingent damage caused by negligence or carelessness that threatened unspecified persons.50 This is the equivalent of punitive damages in diffuse actions that seek to punish the responsible party and redress the damage done to a diffuse collective.

Chevron filed a cassation appeal against the second instance ruling. It will correspond to the Supreme Court of Ecuador to confirm the sentence and either declare it res judicata, or vacate the ruling. Unlike that which is being argued by the ad quem, Chevron found serious violations, such as the lack of jurisdiction of Ecuadorian courts, the misinterpretation of the corporate veil doctrine, procedural fraud, and public order violations concerning evidence and how damages should be measured.51

The legal battle for harms that commenced 50 years ago has lasted over 20 years. Regardless of the fraudulent or malicious actions by plaintiffs and responsible parties alike and regardless of whether the accountable entity is Texaco, Chevron or Petroecuador, it is clear that there is a global need for clear and certain legal framework to prevent, punish and eradicate toxic pollutants given international business relations.

The Ecuadorian case can be used as an example for Mexico's need for punitive damages to avoid abuses in detriment of the environment and future generations. Both enterprises and public owned companies must be sanctioned provided that there is a legal procedure that can be clearly, fairly, quickly and predictably followed.

VII. Punitive Damages and their Alternatives

1. Legal Reforms

At least two questions arise regarding environmental action rulings: to what degree is it possible to restore things to the state in which they were previously kept? And how can we put a price on an environmental violation?

The FCC contains some parameters to regulate the awarding of civil damages; however, these considerations are designed to deal with conventional torts in private law relations and not for environmental damages, which entail administrative and civil violations, and harm caused to the environment. In some cases, this harm represents gigantic catastrophes, the quantification and punishment of which goes beyond repairing damages and interest lies outside the scope of civil law since not just two parties are involved, but rather the entire community seeks reparation and the prevention of ecological offenses.

Corporations may prefer facing and paying public fines than preventing the potential damage because the first would be a more profitable decision, even if said income is generated at expense of potential victims' health and the environment. Another possibility of sanction is corporations' criminal liability. Judges are empowered to order the dissolution or suspension of legal entities whenever crimes are committed on behalf of or with the support of said entities.52 Nonetheless, this sanction does not have a bearing on the responsible parties' economic welfare itself and may leave the company's earnings almost untouched. Therefore, civil adjudication could complement the function of public law.

In other continental law jurisdictions like Argentina, punitive damages have been deemed an invasion of civil law in the scope of public law.53 Nonetheless, there are several factors in the Mexican legal system that may help the use of punitive damages be seen more as an enhancement of administrative law than an invasion. In cases of environmental law, a tort is not only caused by the traditional civil law duty of not causing harm to others, but also by the violation of environmental law regulations. Such public violation is no longer claimed through an administrative procedure, but via civil litigation. Yet the outcome of the trial affects not only the parties, but also an undetermined collective because the diffuse right to a healthy environment is what has been affected.

Furthermore, in collective actions, public agencies like the PROFEPA leave aside their role as authorities to become the representatives of the collective. It is a legal fiction in which public entities act as if they were individuals who intervene not to protect private interests, but the rights of a collective, as happens in criminal or administrative procedures.

Punitive damages may be used as an additional amount awarded and quantified by a judge whenever there is adequate material evidence to measure the damage done in economic terms (i.e., when there are not only tangible but intangible damages caused by the respondent). Once it is proven that the alternative compliance of the decision must be fulfilled, the judge, at his or her discretion, may award not only compensatory damages limited by tangible data, but also punitive damages based on impalpable evidence, as in the case of moral damages.

The possibility of awarding punitive damages and increase plaintiff's patrimony may contradict the non-profit aspect of Mexican collective actions. However, the already existing public fund managed by the judiciary may be used to manage compensatory damages in diffuse actions, as well as additional punitive damages in general. This fund could be used whenever it has been proven in a collective actions procedure that the respondent acted with gross negligence or wanton disregard toward the collective, and when public sanctions are insufficient to punish the responsible party and prevent similar cases in the future. The fund could be also used to include exemplary damages in the Mexican legal system, so these can be used as a deterrent for careless responsible parties, without have to turn these damages into a motivation for lucrative litigation.

Punitive damages must be awarded as an exception rather than a rule. Thus, legislators could order judges to apply punitive damages in addition to compensatory damages when these are insufficient to redress the damage done. In cases of mass torts, proven gross negligence or wanton disregard by the responsible party, traditional tangible damages seem inadequate to measure the damage or insufficient to deter the responsible party or others from committing similar actions. Besides, exemplary damages could be appropriate when the responsible party keeps the profits that would not have generated had it not been for the illicit act.

Another option for legislators is to incorporate punitive damages into environmental law, not as an instrument to protect the collective from harms, but to protect the environment as an autonomous subject of rights, regardless of the damages caused to physical persons. Thus, the responsible party would need to repair the damages caused not only to the collective, but also to the environment, as another legal entity with its own rights. This is the approach proposed in 1972 by Christopher D. Stone, who has advocated for a voice for inanimate objects, so that said objects could have an entity to speak on their behalf and on that of future generations.54

In Mexican environmental actions, compensatory damages would be awarded based on tangible data and managed by the fund in diffuse actions or incorporated into plaintiff's patrimony in collective actions in strict sense or individual homogenous action. In addition to these damages, judges could award punitive damages which would always be managed by the public fund, and these resources could be used not only to promote diffuse rights, but also to protect and repair the environment.

Stone argues that considering the environment as a person would be an appropriate legal fiction to protect nature and future generations. It is a legal obligation to respect nature and so it is not unreasonable to believe there is an independent relation between the polluter and the environment under the circumstances of a violation, although there may be cases in which there are both damage to the environment and damage to individuals, as in the case of catastrophes.55

Stone's proposal has even resonated in the US Supreme Court, in the dissenting opinion of William O. Douglas in Sierra Club v. Morton.'56 The Sierra Club, a membership corporation, tried to block the construction of a skiing development in Mineral King Valley in the Sequoia National Forest in California. The Sierra Club did not claim it was a violation of personal interests, but rather asserted that the project would have a negative impact on the local environment. The majority ruled that the Sierra Club, in its corporate capacity, lacked standing, but it could sue on behalf of any of its members who had an individual interest. Douglas did not share the majority opinion and asserted that individuals may have standing, but that the defense of the environment should correspond to nature itself. Thus, rivers, valleys or beaches could be plaintiffs in cases aimed at defending the interest of said ecological entities and that of every creature dwelling therein, instead of only in the defense of the rights of people.

Overcoming the anthropocentric legal perspective and inspired by the world views of the Aimaras and the Quechuas, the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution now recognizes Pacha Mama or Mother Nature as an autonomous entity with its own legal personhood.57 This legal text expressly states that Nature is entitled to restoration, irrespective of other subjects' obligation to indemnify individuals and groups who depend on the affected ecosystems.

What is really distinctive about the legal relation between polluter and the environment is the way damages are measured. Most natural resources are outside the scope of the market and harms caused to it are difficult to measure. Therefore, Stone proposes that environmental damages should be based on law decrees, rather than proven like traditional civil damages are.58

Based on the constitutional right to a healthy environment, Mexican legislators could adapt the figure of punitive damages as an independent amount to be paid by the responsible party, but is awarded in favor of not the plaintiff, but the environment and managed by the national fund. The method for quantifying said damages could be limited by statutory law and guided by environmental experts at the civil procedure. Legislators could force judges to consider the fines already paid for public procedures with the object of not punishing twice or excessively, but to redress the damage done to individuals and the environment, and to adequately punish in exceptional cases.

Such measures can find express constitutional authorization in the recently reformed fifth paragraph of Article 4 of Mexican constitution, which states that environmental damages generate liability for the polluter.59 One interpretation of this amendment could suggest that this liability is separate from that caused to the collective. Otherwise, the amendment would be repetitive because the domestic system already recognized civil liability for damages done to the environment provided that these torts affected individual plaintiffs.

2. Case Law

In the interval in which punitive damages are implemented in Mexico or if legislators decide not to incorporate them, moral damages and illicit enrichment could be established as transitory measures through adjudication to fulfill similar functions to those of exemplary damages.

Moral damages could be claimed as an additional sum in collective actions, whenever environmental damages also cause a negative effect on the intangible rights of personality of a collective. Likewise, illicit enrichment could be an accessory claim whenever a polluter generates profits at expense of the environment or by endangering or affecting the collective's health and the right to a healthy environment.

Moral damages of civil law jurisdictions share some aspects of punitive damages: both institutions address intangible damages that are difficult to measure, and both take into account the economic welfare and the responsibility of the defendant to confer said amounts. However, as noted by Jorge A. Vargas, moral damages have not been designed by legislators or interpreted by courts as a punitive instrument, but rather as an equity remedy.60 Furthermore, moral damages are not aimed at increasing the patrimony of the plaintiff, but to redress a damage done to moral patrimony. Thus, moral damages could perform a similar role to that of the U.S. civil fine, but these are not equivalent. In Argentina, both institutions, together with traditional compensatory damages, already coexist.61

Punitive damages have been implemented in Argentina under the scope of consumer rights. These consist of an amount of money, in addition to the compensatory damages for the harm actually caused that is incorporated into the plaintiff's patrimony and which proceeds at the request of the latter whenever the supplier fails to meet its obligations in detriment of the consumer.62 Argentinean courts have already granted moral and punitive damages in the same decision. In the Machinandiarena case,63 the court awarded $30,000 Pesos for moral damages and an identical amount for punitive damages in favor of the plaintiff. The claimant was a person with disabilities who was unable to file his consumer complaints against a telephone company because the corporation did not assist the plaintiff by attending his complaint, and refused to adapt its premises by building a ramp for the disabled.

Hence, if the MFC decides to implement punitive damages, this remedy could be compatible with moral damages. The first is aimed at punishing the responsible party for unusually severe torts while the second is to redress intangible damages caused to plaintiff's feelings.

Moreover, the non-profit aspect of Mexican collective actions, together with the public fund controlled by the judiciary, may be used to avoid one of the most controversial issues of punitive damages, i.e. the fact that the amount is awarded to the plaintiff despite the lack of a causal link between punitive damages and the plaintiff if not for the reason that the latter put his or her time and effort into filing the lawsuit. In Mexico, plaintiffs would be motivated by duty, in the case of public agencies, and by collective interest, in the case of non-profit associations. Therefore punitive damages could be used to deter responsible parties and potential wrongdoers, without encouraging lucrative litigation.

Moral damages could be an additional economic award applied in diffuse actions when the responsible party is sentenced to fulfill the judgment through alternative economic compliance, as well as in regular collective and individual homogeneous actions. In diffuse actions, compensatory and moral damages would be managed by the fund, and in other cases, these would be incorporated into the plaintiffs' patrimony.

The gap in the law regarding alternative compliance of diffuse actions could be filled by establishing case law similar to what happens in the constitutional remedy of Amparo Indirecto when it is physically impossible to repair the damage by restoring the enjoyment of fundamental rights. Even when this repair is possible, the material compliance of the judgment could be more harmful to society than the benefit to the aggrieved. In this last case, federal courts could commute the obligation to do for an obligation to give. Thus, judges are allowed to determine an alternative compliance by requiring the responsible authority to repair the harm by paying damages to the petitioner instead of restoring the violation by performing an activity.

The possibility of the alternative execution of judgments is the Amparo procedure, which is provided by law as the equivalent of environmental law. However, the method in which damages are determined is guided by case law and solved as an interlocutory decision. An alternative to exemplary damages can be found in moral damages and illicit enrichment. Federal courts can develop these concepts into collective actions procedures through case law.

The alternative compliance of Amparo rulings is prescribed in section XVI of Article 107 of the Mexican Constitution. Alternative compliance of a judgment in an Amparo is the exception, not the rule, just like the subsidiary fulfillment contemplated in Article 604 of the FCCP. Thus, economic awards in environmental diffuse actions would be rare, applicable only when it is impossible to repair the damage done.

The alternative execution of constitutional judgments is determined incidentally, after it is proven that it is the only way in which the constitutional protection can be granted. This duty may be met through a transaction between the responsible party and the applicant, which in somewhat is equivalent to out-of-court agreements regarding punitive damages, only that in the Mexican constitutional procedure, this agreement can be drafted only once it is evident that the traditional execution is not practical or optimal for society.

Considering that neither the incidental procedure nor the agreement is delineated in the act of Amparo, they are regulated as a supplement by federal jurisprudence and the FCCP.64 Hence, the plaintiff must prove what the appropriate economical amount which will substitute the original obligation for damages liability will be. Thus, any entitled party could sue the presumed tortfeasor for tangible damages, as well as for illegitimate enrichment or moral damages. The first will be the amount for the material damages in the case that the harm to the environment can be reversed, and the latter could perform a similar function to that of exemplary damages in a civil law jurisdiction.

There is no doubt that environmental damages affect the patrimonial interest of individuals, but it is also plausible to argue that the negative effects can also harm moral rights. One toxic spill in the ocean could damage the interests of a collective of fishermen whose patrimonial rights have been affected, but their intangible rights as feelings can also be affected when the ocean is devastated by irresponsible polluters. This in turn deprives them of a natural resource that contributed, indirectly and aesthetically, to the wellbeing of the people who live near the ocean.

The Mexican courts would have to solve the issue on whether to ascertain moral damages or illicit enrichment as appropriate pretensions claimable through collective actions. Moral damages may be necessary to remediate the difficulty of measuring intangible harms. Similarly, illicit enrichment may be necessary to eliminate the illicit profits generated by the tortfeasor. Thus, a restrictive interpretation that only damages can be claimed in collective damages, but not so that unjust enrichment has the effect of letting the polluter go almost unpunished, leaving its profits intact.

The underlying justification of illicit enrichment is that by neglecting environmental law, the responsible party harmed the environment and other individuals. This detriment which once translated into a profit for the offender must be repaired not only to the extent in which the complainants were injured, but also to the extent in which the offender obtained economic benefits by compromising the safety of others and the ecological balance.65

Environmental illegitimate enrichment will be proven in trial simply by proving that the responsible party gained profits in detriment of the environment or of the right to a healthy environment, as well as by proving that this detriment was not justified by law.

An administrative fine of six million pesos is appropriate for most environmental infractions, but it will be insufficient for environmental disasters. Thus, even when applied together, ordinary damages and administrative fines will not be sufficient to counteract the bad faith of pollutants. It is indispensable to take into account consider the illicit profits derived from corporate savings in security measures and bad planning.

Hence, through the figure of illegitimate enrichment, this claim would be appropriate only in exceptional cases, such as environmental catastrophes, and the amount of damages would be guided by experts and determined by judges in an interlocutory procedure. Far from being an unreasonable or spurious act on behalf of the judiciary, similar legal instruments have been constructed or implemented by Mexican judges through case law. This is the case of the implementation of the "corporate veil doctrine,"66 the doctrine of the misrepresentation, or ideological falsehood on credits such as promissory notes.67

It is essential to have the efficient legal institutions to deal with environmental damages. Although the ideal context in which punitive damages could have been instituted was through statutory reformation on the hands of federal legislators, the latent need for this legal institution may develop gradually by means of collective actions cases, and consequently through federal case law.

* Bachelor of Laws from the University of Guadalajara. Head of Administrative Support at the General Counsel's Office of the University of Guadalajara. Master of Jurisprudence (Mjur) from the University of Sydney. Current PhD student at Macquarie University (Sydney) and scholarship holder from the University of Guadalajara.

1 JOHN W. WADE, VICTOR E. SCHWARTZ, KATHRYN KELLY, DAVID F. PARTLETT, PROSSER, WADE AND SCHWARTZ'S ON TORTS 508 (The Foundation Press, 9th ed, 1994). [ Links ]

2 Id.

3 Kemezy v. Peters, 79 F.3d 33 (7th Cir. 1996) (Posner. J).

4 WILLIAM M. LANDES AND RICHARD POSNER, THE ECONOMIC STRUCTURE OF TORT LAW 161 (Harvard University Press, 1987). [ Links ]

5 Kemezy v. Peters, 79 F.3d at 4.1.

6 Day v. Woodworth 54, U.S 363 (1851).

7 Jones v. Kelly (1929) 208 Cal. 215 [280 P. 942]. In this case, the plaintiffs sued their landlord in tort after the landlord had intentionally cut off the water supply to the leased dwelling.

8 Comunale v. Traders & General Ins. Co. (1958) 50 C2d 654.

9 Crisci v. Security Ins. Co. (1967) 66 Cal.2d 425.

10 Gruenberg v. Aetna (1973) 9 C3d 566.

11 Richardson v. Employers Liab. Assur. Corp. (1972) 25 Cal.App.3d 232.

12 Liebeck v. McDonald's Restaurants, PT.S, Inc., No. D-202 CV-93-02419, (1995) WL 360309.

13 Exxon Shipping Co. v. Baker, 554 U.S. 471 (2008).

14 Roli Varma and Daya R. Varma, The Bhopal disaster of 1984, 25 BULLETIN OF SCIENCE, TECHONOLGY & SOCIETY 1, 37-45 (2005). [ Links ]

15 In Re: Union Carbide Corporation Gas Plant Disaster at Bhopal, India in December 1984, MDLNo. 626; Misc. No. 21-38 (JFK) ALL CASES 634 F. Supp. 842; (1986).

16 John Eliot, Bhopal's continuing disaster, FT.com, Dec. 2, 2009. Available at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/f73a81ec-df0e-11de-be8e-00144feab49a.html#axzz2JsWF0vrS (last visited Feb. 4 2013). [ Links ]

17 Supra note 15.

18 John G. Fleming, Mass Torts, 42 (3) THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW 507, 508 (Summer, 1994). [ Links ]

19 505 (b) 1 (A) of the Clean Water Act 86 Stat. 816 (1972) provides a deadline of 60 days, for the perpetrator to take actions to redress the damage, and only then, the citizen suit may be filed.

20 See Código Federal de Procedimientos Civiles [C.F.P.C.] [Federal Civil Procedure Code], as amended, art. 578, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O], 30 de Agosto de 2011 (Mex. [ Links ]).

21 Fed, R. Civ. P. Rule 23 dictates the requirements for federal class action lawsuits.

22 Daniel C. Lopez, Collective confusion: FLSA collective actions, Rule 23 class actions, and the Rules Enabling Act, 61 Hastings Law Journal 1, 277 (2009). [ Links ]