Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tropical and subtropical agroecosystems

On-line version ISSN 1870-0462

Trop. subtrop. agroecosyt vol.14 n.2 Mérida May./Aug. 2011

Revisión

Agronomic and forage characteristics of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.

Características agronómicas y forrajeras de Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.

Leonor Yalid Manríquez-Mendoza1*, Silvia López-Ortíz1, Ponciano Pérez-Hernández1, Eusebio Ortega- Jiménez1, Zenón Gerardo López-Tecpoyotl2, Manuel Villarruel-Fuentes3

1 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Veracruz, Km. 88.5 Carretera Federal Xalapa-Veracruz, Tepetates, Manlio Fabio Altamirano, Veracruz. México. * Corresponding Author *E-mail: lymanriquezm@colpos.mx

2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Puebla, Carretera México-Puebla Km. 125.5 s/n Pablo Momoxpan, San Pedro Cholula, Puebla, México.

3 Instituto Tecnológico de Úrsulo Galván, Km. 4.5 Carretera Cardel-Chachalacas, Úrsulo Galván, Veracruz, México.

Submitted November 12, 2009

Accepted July 12, 2010

Revised received December 06, 2010

Abstract

Native trees are an important source of forage for livestock, particularly in regions having prolonged dry periods. Some tree species have fast growth rates, good nutritional quality, and the ability to produce forage during dry periods when the need for forage is greater. Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. is a tree native to tropical America that has a high forage potential. This species is mentioned in a number of studies assessing the forage potential of trees in a diverse array of environments and vegetation communities, but little is known about its agronomic management and there is a lack of published information on adequate management and cultivation of this species as a forage tree. There is enough information on the nutritional value of the species, but supplementation with this forage and resulting animal responses have not been extensively studied. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the available literature for information on the presence, management, and forage quality of G. ulmifolia in production systems with domestic ruminants.

Key words: Protein bank; Guazuma ulmifolia; seed scarification; silvopastoral systems.

Resumen

Los árboles nativos son una fuente importante de forraje para el ganado, sobre todo en regiones con época de estiaje prolongada. Algunas especies arbóreas son de rápido crecimiento y buena calidad nutricional, además de tener la capacidad de producir forraje durante la época seca, cuando la necesidad de forraje es mayor. El guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.) es un árbol nativo de América tropical que tiene un alto potencial forrajero y del que aún se conoce poco sobre su manejo agronómico. El guácimo es una especie que aparece en muchos estudios de diagnóstico de especies forrajeras en diversos sitios y asociaciones de vegetación, pero existe escasa información publicada sobre su manejo agronómico adecuado para ser cultivado como árbol forrajero. Existe información sobre el valor nutricional del guácimo, aunque la suplementación y la respuesta animal con esta especie tampoco han sido estudiadas de manera extensa. Por lo tanto, el objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la literatura existente sobre la presencia, el manejo y la calidad forrajera del guácimo en sistemas productivos con rumiantes domésticos.

Palabras clave: Banco de proteína; escarificación de semillas; sistemas silvopastoriles.

INTRODUCTION

Guacimo is a tree native to tropical Latin America with good forage qualities, and is found from Mexico to southern Brazil, and in the Caribbean. This tree belongs to the family Sterculiaceae, genus Guazuma and species ulmifolia Lam. (CATIE, 2006). The common names are varied and include guacimo, guazamo, caulote, pixoy, guacimo de ternero, majagua de toro, yaco and granadillo. The tree is characteristic of zones with well defined dry seasons and savanna vegetation, and pastures in hot-humid areas (Nieto et al., 2006; Lopez et al., 2006), although it also grows in more humid ecosystems, in open spaces, along edges of highways and rivers, in cultivated areas, pasturelands and secondary vegetation (Lopez et al., 2006; Ascencio, 2008). In the central part of the state of Veracruz, Mexico, this species has evolved in regions where precipitation is seasonal and very marked, with dry periods lasting up to eight months (Lopez et al., 2006).

Guacimo is considered a multipurpose tree because of the great variety of products and services it provides to agriculture, ranching, the cosmetics industry and medicine. Berenguer et al. (2007) mention its antihypertensive, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties; Alonso-Castro and Salazar-Olivo (2008) highlight its use in countering diabetes; its use in cosmetics, candies, beverages, omelets, atole and pinole are reviewed in EMB (2007); in agroforestry the tree serves as a living fence and shade for resting cattle (Torres et al., 2006); and it provides structure and protection for flora, fauna and sources of water for soil enrichment (Beetz, 2001; Jimenez and Hernandez, 2001), thus helping to conserve natural resources. Its soft wood is used in the manufacture of artisanal crafts, equipment for picking fruits, house construction, furniture, fence posts, livestock facilities, and is a source of firewood and coal (Giraldo et al., 1995; Nieto et al., 2006). G. ulmifolia is also considered to be an important forage species in tropical regions with low precipitation and soil productivity (Giraldo et al., 1995; Lopez et al., 2003, 2006; Villa et al., 2009). The objective of this review is to present information on the agronomic and forage characteristics of guacimo.

Desirable characteristics of forage trees

Potential forage trees should possess certain characteristics that allow them to adapt to their environmental conditions and to prolong their productive life (Benavides, 1998; Febles and Ruiz, 2008). These characteristics are grouped as follows:

1) Agronomic characteristics

a) Rapid growth

b) Adaptation to soils having low fertility

c) Resistance to fires, diseases and plant pests

d) High biomass production production

e) Forage production during dry seasons

f) High seed production and easy propagation

g) High survival capacity when established in the field

2) Capacity to associate to other plants

a) Positively interact with other trees and grasses

b) Posses a deep root system

c) Permits the growth of other plants under their canopies

3) Defoliation response

a) Adequate response to pruning and frequent trimming and browsing

b) High production of buds after defoliation

4) Nutritional value and consumption

a) High passage rate through the digestive tract

b) High nutritional value

c) High hedonic value for domestic ruminants

d) Low content of secondary metabolites that will not affect voluntary consumption

e) Improve performance of livestock

General botanic and biological aspects of guacimo

Guacimo is a tree of medium size, although the canopy height of some trees has been reported to be 25 m (EMB, 2007). It is a much ramified tree, with a rounded, open and extended. Its leaves are alternate and simple, from 3 to 13 cm long and 1.5 to 6.5 cm wide, with an oval or lanceolate form, serrate margins, dark green color and rough and scabrous texture on the dorsal surface. Its flowers are distributed in panicles from 2 to 5 cm long, having the form of a star with a white-yellowish, or brown color and sweet smell, and a diameter of 5 mm. The trunk diameter can reach 80 cm (EMB, 2007), is nearly straight and ramified near the base with long branches extended horizontally and at times hanging. The tree has fissured external bark that is grayish-brown in color, while the internal bark is fibrous, yellow to brown-red, with a sweet to astringent flavor (Francis, 1991). The fruits have the form of a capsule from 3 to 4 cm long, with numerous conical protuberances on the surface and are dark coffee to black in color; when mature they have a sweet smell and flavor (EMB, 2007). The seeds are hard in consistency, with lentil-like form, a size less than 1 mm, and are brown in color, although this can vary. The number of seeds per fruit varies from 40 to 80 and the quantity is not related to fruit length or diameter (Leyva, 2003).

In Costa Rica, the tree flowers from March to April (Giraldo, 1998), in Puerto Rico from April to October (Francis, 1991), and in Mexico from May to September (Nieto et al., 2006). Fruit maturation in guacimo varies according to the climatic characteristics of the location in the dry tropics of Mexico. It takes place primarily during the dry season (Contreras et al., 1995; Palma and Roman, 2003; Manriquez et al., 2007), but can occur almost all year (from September to April). In Nicaragua fruiting occurs from February to May during the dry season (Zamora et al., 2001). In mixed forest areas of Brazil, the fruits mature during August and September and remain on the tree until November (De Araujo et al., 1999), while in Mexico this process occurs from March to December.

On the other hand, guacimo is also a deciduous tree; its leaves begin to age during the dry season for periods of different duration. In some climates the periods are short (EMB, 2007) or long, but the time will depend chiefly on the duration of the dry season. This natural leaf drop helps to avoid loss of moisture (Ortega, 2009).

Propagation of guacimo

Guacimo propagates sexually (seeds) and asexually (vegetative). Sexual reproduction in this species is the most common, and this has been found to be the best form for artificial propagation (Villarruel et al., 2007).

Natural dispersal of guacimo seeds is by means of consumption of the mature fruit by birds and mammals (primarily bats and cattle) (Ferguson et al., 2007). This form of dispersal allows the seeds to germinate easily. For controlled propagation of guacimo, the first step is the harvesting of mature fruits (Figure 1) directly from the tree or the soil, however in this last case the fruits should not be infested with larvae (Manriquez et al., 2007). The fruits are then split open and the seeds are extracted with smooth forceps or probes, or with aid of blunt scissors. The seeds are then cleaned to remove all fruit residue. Seed harvesting varies according to the region, because climatic conditions affect fruit ripening (Giraldo, 1995; Ku et al., 1998; Calderon and Lara, 2007).

Under natural conditions in the absence of herbivores/frugivores, the rate of seed germination is low (Villarruel et al., 2007; Hermosillo et al., 2008), since they require the process of scarification to achieve a high percentage of germination. To scarify the seeds, Sanchez et al. (2004) suggest the seeds be submerged in water at 100 °C for 10 sec and then soaked in water at room temperature for 24 hours. However, Villarruel et al. (2007) recommend soaking the seeds in water at 80 °C for 8 to 10 min, and then leaving them in water at room temperature for 24 to 36 hours to assure 95 % germination, although 5 min in water at 80 °C is sufficient (Manriquez et al., 2007). After this processing, the seeds are washed in a finemeshed screen with running water until the mucilage is removed, and left to dry in the shade (Figure 2).

The seeds germinate from 4 to 8 days after sowing, and they can germinate in bags or seedbeds; in both cases they need shade during germination. If they sprout in a seedbed, then when the seedling produces two true leaves (approximately eight days after sprouting), they can be transferred to polyethylene bags filled with soil (Lopez et al., 2006; Manriquez et al., 2007). Seedlings should be provided with 50 % shade and daily irrigation for eight days, and subsequently every other day, so as to stimulate ligneous growth in stems and branches. They can be fertilized with N-P-K in the proportion 10-30-10, using 3 to 4 g per plant (Villarruel and Ruiz, 2004).

No data on the management of guacimo exists for nurseries; only Tamayo and Orellana (2006) in the Yucatan, and Manriquez et al. (2007) in central Veracruz state reported that germination in nurseries is carried out in May, one to two months before the rainy season begins.

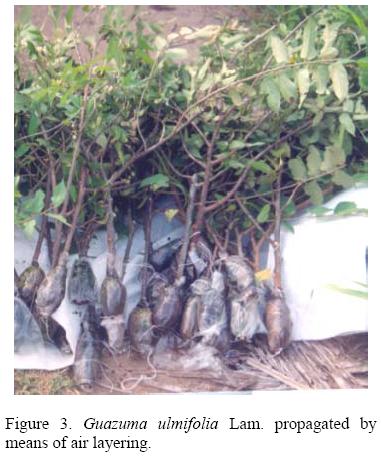

As for asexual propagation, Villarruel et al. (2007) obtained 35 % survival when reproducing guacimo by means of air layering (Figure 3), while 42 % survival was achieved using plant cuttings 20 cm long and 1 cm wide, and using a substrate containing 65 % soil and 37.5 % compost and other materials.

Considerations for the establishment of guacimo in the field

To establish a guacimo plantation, whether in a nursery or in the field, the climate, rainy season, soil type and slope must be considered (Tamayo and Orellana, 2006). Few reports exist in the literature referring to the conditions and requirements for transplanting guacimo to the field. According to Villarruel et al. (2005), guacimo can be transplanted during three or four months of age, when the plant has reached a height of 38 cm. Manriquez et al. (2007) also indicate that transplantation may be performed when the plants are between 1 and 2 months of age, and 20 to 30 cm in height. CATIE (1991) mentions that the plants should be protected from the air and sun during transportation. Planting of young trees should be carried out during the rainy season, preferably at the beginning, so that they have the opportunity to develop over the entire period of rains (Manriquez et al., 2007). Tamayo and Orellana (2006) reported 100 % survival of guacimo when established in places receiving 1,200 mm of precipitation in the Yucatan, Mexico.

The spatial arrangement of guacimo trees in the field depends on the purpose and type of system desired. Trees have been planted using simple or double hedge row designs (Tamayo and Orellana, 2006; Villa, 2009), or under a design in staggered formation such that the plants form equilateral triangles (Villarruel et al., 2007). Planting space between trees in fodder banks is commonly 1 to 1.5 m with row spaces of 1.5 m (Lopez et al., 2006; Figure 4), or in 4 m wide alleys for silvopastoral systems (Villa, 2009; Manriquez., 2010); Tamayo and Orellana (2006) have cultivated this species with 1.25 m of space among plants.

Management of guacimo in production systems

The age of the trees at the moment of their first pruning is very important because this practice determines the subsequent growth and development of the stems and roots, impacting tree performance (Francisco, 2003). Although the best age to practice the first pruning for this species is not known, Holguín and Ibrahim (2004) mention that at the age of six months after its establishment in the field, consumption by animals can begin, while Lopez et al. (2006) performed a first prone to trees 6 months old. Lopez et al. (2006) suggest a traditional pruning of a guacimo forage bank to leave main stems at 60 cm of height, and main branches and secondary branches at 40 cm of length from the base of the stem. Francisco (2003) suggests that an acceptable time to define intervals of pruning in trees exists when the plants possess between 50 and 60 % edible foliage. According to Leyva (2006), guacimo has shown favorable response and resistance to cattle grazing pressure. In this respect, Lopez et al. (2006) indicate that at 6.3 months of establishment in the field, sheep can initiate grazing without damaging or compromising plant survival. Nevertheless, Villa (2009) reported that when cattle grazing was practiced in a silvopastoral system with trees at one year of age, the development of the trees was delayed, although their survival was unaffected.

On the other hand, plant age is important for biomass production; greater vegetative growth provides greater production of biomass. Plant height also positively influences the quantity of biomass produced (Giraldo et al., 1995). Guacimo biomass production has been evaluated mostly for trees growing naturally in different places, and not for trees growing in plantations at high densities and/or under more controlled conditions. Table 1 presents the diverse systems of guacimo management and their biomass production.

In general, the production of biomass and fiber increases over long periods of pruning or grazing, and the percentage of crude protein declines. However, over smaller intervals of time, biomass and fiber are reduced and the amount of raw protein increases (Lizarraga et al., 2001). In Tabasco, Mexico, Reyes (2006) used four month pruning intervals during the year and obtained 1.5 kg DM tree-1 with 41.9 % edible foliage. In turn Lopez et al. (2006) obtained 2.6 t DM ha-1 from a forage bank at the first pruning, while Villa (2009) achieved 1.7 t DM ha-1 in a 7 month period in a silvopastoral system with 4,000 one year old trees ha-1

Forage quality of guacimo

Various investigators (CATIE, 1991; Lizarraga et al., 2001; Zamora et al., 2001; Palma and Roman, 2003) have evaluated the nutritional quality of guacimo foliage and fruits with variable results. The quality depends on the soil and climatic conditions of the location, time of year, age of regrowth, plant management and animal consumption (Lopez et al., 2008). Crude protein (CP) content of guacimo fruit in forage varies; the minimum reported in fruits was 5.8 % in the humid tropics of Chiapas, Mexico, (Pinto et al., 2004), and the maximum was 11.3 % in ground dry fruit from the tropical dry climate of Colima, Mexico (Contreras et al., 1995). In Costa Rica, Giraldo (1998) reported CP of 5.5 % in foliage from trees at medium density (2,795 trees ha-1) in winter, while Araya et al. (1994) obtained 23 % CP in a premontane forest. In tropical sub-humid Veracruz, Mexico, during the rainy season, in poor soil conditions, Villa (2009) also reported 23 % CP. There is greater CP in leaves than in stems, ranging from 16 % (CATIE, 1991) to 19.5 % in leaves (Araya et al., 1994), and from 5.2 % (Lizarraga et al., 2001) to 8.1 % in stems (Araya et al., 1994).

The digestibility of edible guacimo biomass depends on the age of regrowth and the position of the branches. In fruits, DDM ranges between 49 % and 66 % for ground mature fruit, with a greater digestibility if NaOH is added to the ground fruit (Contreras et al., 1995). In foliage, dry matter digestibility values range from 41 % (Pinto et al., 2004) to 94 % (Giraldo, 1998). Other authors have reported intermediate values of digestibility (47.2 %) in the Yucatan (Bobadilla and Ramirez, 2006), and high values (60 %) with 4 month regrowth in Tabasco, Mexico (Reyes, 2006).

Ash content permits an evaluation of the inorganic matter in forage, and it varies little. In fruit, CATIE (1991) reported values of 5.5 %, while Contreras et al. (1995) reported 11 %, the maximum value reported for mature fruits. Ash content in foliage ranges from 8.6 % in Costa Rica (CATIE, 1991) to 14 % in four year old guacimo plants and 70 days of regrowth during the rainy season in Veracruz, Mexico (Lopez, 2008).

The range for neutral detergent fiber (NDF) of fruits and foliage also has been reported to be wide. The lowest value for fruits is 46.1 % reported by Pinto et al. (2004) in Chiapas and the highest is 60 % reported in Colima (Palma and Roman, 2003), both in Mexico. In foliage, 41.1 % of NDF has been found in trees used by cows in the Yucatan (Bobadilla et al., 2006), and 74 % in forage of 70 day-old regrowth supplemented to sheep in Veracruz, Mexico (Lopez, 2008). Acid detergent fiber (ADF) for fruits ranges from 29.4 % to 46 % in feeds containing urea and NaOH (Contreras et al., 1995), while a range from 26 % (Lizarraga et al., 2001) to 57 % (Villa, 2009) exists for one year old plants during the rainy season in Veracruz, Mexico.

The lowest value reported for fruit cellulose is 19.2 % (Contreras et al., 1995), and the highest is 30 % (Palma and Roman, 2003), both reported from Mexico. Araya et al. (1994) reported cellulose content of guacimo foliage to be 19 % in tropical premontane forest in Costa Rica, while Lopez (2008) reported 35 % in Veracruz, Mexico. Palma and Roman (2003) found fruit hemicellulose to be 6.1 %, and Contreras et al. (1995) reported 14 %, both from Colima, Mexico. Values of 8 % in Brazil (De Araujo, 1999) and 31 % in Veracruz, Mexico (Lopez, 2008) also have been reported.

Information on the lignin content in fruits and foliage is scarce. Contreras et al. (1995) reported 9.0 % to 26.8 % in fruits from Colima, Mexico, while in the foliage a concentration of 3.4 % was indicated from Veracruz, Mexico (Lopez, 2008).

Guacimo forage is known to contain tannins. Lopez et al. (2004) analyzed the tannin content of guacimo DM from 20 tree species in the Mexican tropics, and found free (129.7 g kg-1 DM) and total condensed tannins (205.9 g kg-1 DM) in the forage. However, the content of this metabolite as with many others varies with forage age, location and time of year (Scull, 2004). Cardenas et al. (2003) found 1.2 g kg-1 tannins in the foliage of guacimo from areas receiving 1,000 mm of precipitation, Lizarraga et al. (2001) reported 3.5 g kg-1 of DM, and Bobadilla and Ramirez (2006) reported 6.3 g kg-1 from the Yucatan, Mexico. The content of these metabolites is important because it is negatively related to digestibility and can affect the consumption and nutrient value of the forage (Soca, 2004). Yet, little information exists on the content of tannins in guacimo and their effect on animal consumption and productivity.

Consumption

Foliage consumption by cattle as well as forage quality is reflected in changes in the reproductive and productive parameters of the animals. Ku et al. (1998) and Lopez et al. (2008) indicated that supplementing ruminant diets with forage trees stimulates food consumption. Upon offering several species of trees to goats for consumption, Vallejo et al. (1994) observed that consumption increased and that the goats had a greater preference for guacimo foliage compared to other preferred trees.

Evaluations of the consumption of foliage and fruits of guacimo have been reported in sheep. Supplementation with fruits stimulates the voluntary consumption of DM, increases the bacterial population of the rumen and reduces the population of ciliate protozoa (Navas et al., 1999). In the Yucatan, Cardenas et al. (2003) preserved guacimo foliage in a microsilo, and demonstrated that it had good organoleptic characteristics and chemistry for animal consumption, with 8.4 % CP. In turn, Palma and Roman (2003) supplemented with fruit meal from five species including guacimo and obtained greater consumption of guacimo, with 160.8 ± 5.1 g DM animal-1, yielding 94 % acceptance by hair lambs.

Some studies have indicated that guacimo is a forage preferred by sheep (Sosa et al., 2004). Lopez (2008) offered chopped forage ad libitum to sheep and observed greater consumption when guacimo was offered alone (107.9 g kg-0.75) compared to only grass, achieving a weight gain of 50 g animal-1 day-1. Medina (1994) evaluated the consumption of several forage trees along with supplementation of guacimo for young grazing goats and obtained a consumption of 608 g animal-1 day-1 and a weight gain of 71 g animal-1 day-1.

With regard to the consumption of guacimo by cattle, Perez et al. (2006) evaluated the consumption and weight gain of cattle that received a combination of guacimo and pasture grass (Megathyrsus maximum (Jacq.) B.K. Simon & S.W.C. Jacobs var Tanzania), and those that only were fed with grass (M. maximum var Tanzania). They obtained greater weight from systems having guacimo and pasture grass (P. maximum var Tanzania) (486 g animal-1 day-1) in comparison with pasture grass monocultures (369 g animal-1 day-1). Including guacimo as a supplement to the diet of cattle influences their consumption of DM and performance (Bobadilla et al., 2006). In Nicaragua, one of the three native forage tree species that is most abundant is guacimo, where the foliage and fruits are used as supplements for cattle during the dry season (November to April). Zamora et al. (2001) reported a consumption of guacimo foliage of 3.6 kg cow-1 day-1, and from 0.9 to 2.3 kg animal-1 day-1 of fruits for calves and lactating cows.

Presence of Guazuma ulmifolia in production systems

Many studies have reported the presence of G. ulmifolia in a variety of locations and production systems. CATIE (1991) indicated the presence of this species in natural associations of secondary forests in Central America, and it has been found in thorn cloud and tropical forests (EMB, 2007). In Veracruz, Mexico, Villegas et al. (2003) found it between 5 to 50 masl in low subcaducifolious forest, and between 10 and 900 masl in deciduous forest. Flores et al. (1998) found G. ulmifolia in humid premontane forest in Costa Rica. In Mexico, Francis (1991) reported the presence of guacimo in the initial succession stages of disturbed forests, and associated with species such as Acrocomia aculeate (Jacq.) Lodd. Ex Mart. and Heliocarpus spp. Grande et al. (2006) found guacimo in rain forest. Giraldo et al. (1995) reported the presence of this species in Colombia in tropical dry forest in the process of regeneration, and Zamora et al. (2001) reported its presence in the dry forests of Nicaragua. Some studies discuss the management of this tree in pasturelands (Francis, 1991; Pinto et al., 2004; Torres et al., 2006; Villa et al., 2009), while others have been carried out in established plantations. In Mexico, this species has been evaluated in forage banks and established silvopastoral systems (Lopez et al., 2006), in agrosilvopastoral systems in coastal plains, ridges, mountains and high plateaus of Veracruz (Torres et al., 2006), and in established silvopastoral systems with intensive grazing in Chiapas, Mexico (Perez et al., 2006). In Cuba, guacimo is predominantly found in association with natural vegetation in silvopastoral systems having low levels of management (Acosta et al., 2003). In Veracruz, Bautista (2009) reported the existence of guacimo as a result of natural succession in pastures and agricultural fields.

Products and services from Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.

Guacimo is characterized as a multiple use species that provides a variety of products and services in diverse production systems in tropical regions (CATIE, 1991). It has a productive capacity and quality forage in livestock systems (Giraldo, 1998; Lopez et al., 2006), and its fruits are an alternate source of food for cattle during the dry season (Palma and Roman, 2003; Sosa et al., 2004). As a forest resource, it serves as a living fence, a source of shadow and rest for cattle, and as wind breaks (Lopez et al., 2006; Torres et al., 2006). As a medicine, fruits have been reported to aid in countering diabetes (Martinez, 2006; Alonso-Castro and Salazar-Olivo, 2008), but it also has antihypertensive, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, and an undocumented property as a hemicoagulant used in central Mexico. Moreover, this species has also been used to manufaacture cosmetics, candies, beverages, omelets, hot drinks and pinole (a traditional Mexican beverage) (EMB, 2007). Its soft wood is used in the manufacture of artisanal crafts, equipment for picking fruits, broomsticks, for house construction, furniture, fence posts, livestock facilities, and is a source of firewood and coal (Giraldo et al., 1995; Nieto et al., 2006; Bautista et al., 2011 in press). Trees in landscapes provide conditions for bird nesting and wildlife protection. A great variety of plant species grow and under their canopies and falling leaves provide organic material and microorganisms to increase the soil humidity and the use of water, light and nutrients, to fortify the ground cover and enrich the soils (Beetz, 2001; Jimenez and Hernandez, 2001; EMB, 2007).

CONCLUSIONS

G. ulmifolia Lam. is a species that possesses desirable characteristics as a forage tree. Its crude protein content, rusticity, resistance, persistence and palatability make it an important alternative source of protein for ruminant diets, especially in tropical regions during the dry season when the availability of forage for cattle is significantly reduced. It is a species with the potential to improve livestock performance when they are provided with other forage species of lower nutritious quality. Besides contributing to livestock diets, the presence of guacimo in pastures increases biodiversity, favors water conservation and soil fertility. Further research is necessary on the performance of sheep and cattle supplemented with guacimo to better understand its potential as a source of forage in tropical silvopastoral systems.

REFERENCES

Acosta, G.Z.G., Godínez, C.D. and González, R.M. 2003. Potencial silvopastoril del municipio Jimaguayú en Camagüey, Cuba. In: II Conferencia Electrónica sobre Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en América Latina. Depósito de documentos de la FAO. URL: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAP/frg/AGROFOR1/bnvdes23.htm. (accessed May 15, 2008) pp. 157-169. [ Links ]

Alonso-Castro, A.J. and Salazar-Olivo, L.A. 2008. The anti-diabetic properties of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. are mediated by the stimulation of glucose uptake in normal and diabetic adipocytes without inducing adipogenesis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 118:252-256. [ Links ]

Araya, J., Benavides, J., Arias, R. and Ruiz, A. 1994. Identificación y caracterización de árboles y arbustos con potencial forrajero. In: Benavides J.E. (ed.). Árboles y Arbustos Forrajeros en América Central. CATIE (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza), Costa Rica. pp. 31-63. [ Links ]

Ascencio, R.L. 2008. Caracterización de especies leñosas en sistemas ganaderos, de los Municipios de Tlapacoyan, Misantla y Martínez de la Torre, Veracruz, México. Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias. Programa de Agricultura Tropical Sostenible. CATIE (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza), Costa Rica. 119 p. [ Links ]

Bautista, T.M. 2009. Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles en el Limón, Municipio de Paso de Ovejas, Veracruz, México. Tesis de Maestría. Colegio de Posgraduados. Campus Veracruz. Veracruz, Mexico. 70 p. [ Links ]

Bautista, T. M., 2011. Sistemas agro y silvopastoriles en la comunidad El Limón, Municipio de Paso de Ovejas, Veracruz, México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems. (in press). [ Links ]

Beetz, A. 2001. Sustainable Pasture Management. ATTRA. (Appropriate Technology Transfer for Rural Areas). pp. 1-12. [ Links ]

Benavides, J.E. 1998. Árboles y arbustos forrajeros: Una alternativa agroforestal para la ganadería. En: Memorias de una conferencia electrónica: Agroforestería para la producción animal en Latinoamérica. FAO-CIPAV. Cali, Colombia. URL: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAP/frg/AGROFOR1/bnvdes23.htm. (accessed May 15, 2008). pp. 1-26. [ Links ]

Berenguer, B., Trabadela, C., Sánchez-Fidalgo, S., Quílez, A., Miño, P., De la Puerta, R. and Martín-Calero, M.J. 2007. The aerial parts of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. protect against NSAID-induced gastric lesions. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 114:153-160. [ Links ]

Bobadilla, H.A.R., Sandoval, C.C. and Ramírez, A.L. 2006. Rendimiento de leche de vacas en pastoreo complementadas con follaje de arbóreas del trópico subhúmedo. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 170-173. [ Links ]

Bobadilla, H.A.R. and Ramírez, A.L. 2006. Contenidos nutrimentales de ocho arbóreas forrajeras nativas de la República Mexicana. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 118-120. [ Links ]

Calderón, Z.M. and Lara, B.J. 2007. Aspectos tecnológicos y financieros de la reproducción de plantas de Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. para un sistema silvopastoril. Tesis de licenciatura. Instituto Tecnológico de Huejutla. Huejutla de Reyes, Hidalgo. 34 p. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M.J.V., Sandoval, C.C.A. and Solorio, S.F.J. 2003. Composición química de ensilajes mixtos de gramíneas y especies arbóreas de Yucatán, México. Técnica Pecuaria México. 41:283-294. [ Links ]

CATIE. (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza). 1991. Guácimo Guazuma ulmifolia. Especie de árbol de uso múltiple en América Central. CATIE, Serie Técnica, Informe Técnico No. 165. Turrialba, Costa Rica. 69 p. [ Links ]

CATIE. (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza). 2006. Guazuma ulmifolia (Lam) Sterculiaceae. Un árbol de uso múltiple. Colección Materiales de Extensión. OFI-CATIE: (Oxford Forestry Institute/ Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza). URL: http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/adc/downloads/capitulos_especies_yanexos/guazuma_ulmifolia.pdf. (accessed May 30, 2006). pp. 569-572 [ Links ]

Contreras, D., Gutiérrez, C.H.L., Ramírez, C.T. and López, R.A. 1995. Mejoramiento del valor nutritivo de frutos secos de guácima (Guazuma ulmifolia) con urea e hidróxido de sodio. Archivos de Zootecnia. 44:49-53. [ Links ]

De Araujo, M., Correia, N.J. and Aguiar, I.B. 1999. Desarrollo ontogénico de plántulas de Guazuma ulmifolia (Sterculiaceae). Revista Biología Tropical. 47:785-790. [ Links ]

EMB. (Encyclopédie Méthodique, Botanique). 2007. Guazuma ulmifolia (Lam.). URL: www.fs.fed.us/global/íítf/Guazumaulmifolia.pdf. (accessed March 31, 2007). 3:246-249. [ Links ]

Febles, G. and Ruiz, T.E. 2008. Evaluación de especies arbóreas. Taller sobre investigación en Sistemas Agro silvopastoriles o Agroforestería Pecuaria. In: IV Reunión en Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. Universidad de Colima. Colima, México. May 12-16. pp. 11-33. [ Links ]

Ferguson, B.G., Miceli, M.C.L., Pascasio, D.G., Díaz, V.J.L. and Cortez, J.P. 2007. Puede el ganado ayudarnos a sembrar árboles? In: Alemán, S.T., Ferguson, B.G. and Medina, J.F.J. (eds.). Ganadería, Desarrollo y Ambiente: Una Visión para Chiapas. México, pp. 57-58. [ Links ]

Flores, R.O.I. 1994. Caracterización y evaluación de follajes arbóreos para la alimentación de rumiantes en el departamento de Chiquimula, Guatemala. In: Benavides, J.E. (ed.). Árboles y Arbustos Forrajeros en América Central, Vol. 1, Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE), Costa Rica. pp. 117-133. [ Links ]

Flores, O.I., Bolívar, D. Ma., Botero, J.A., Ibrahim, M.A. 1998. Parámetros nutricionales de algunas arbóreas leguminosas y no leguminosas con potencial forrajera para la suplementación de rumiantes en el trópico. Livestock Research for Rural Development. 10:1-10. [ Links ]

Francis, J.K. 1991. Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. Guácima. SO-ITF-47. New Orleans, LA: USDA Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station, pp. 255-259. [ Links ]

Francisco, A.G. 2003. Manejo estratégico de las defoliaciones en especies arbóreas. Pastos y Forrajes. 26:185-195. [ Links ]

Giraldo, L.A., Botero, J., Saldarriaga, J. and David, P. 1995. Efecto de tres densidades de árboles en el potencial forrajero de un sistema silvopastoril natural en la región Atlántica de Colombia. Agroforestería en las Américas. 8:14-19. [ Links ]

Giraldo, V.L.A. 1998. Potencial de la arbórea guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia) como componente forrajero en sistemas silvopastoriles. In: Memorias de la conferencia electrónica sobre Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en Latinoamérica, pp. URL: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAP/frg/AGROFOR1/bnvdes23.htm. (accessed May 15, 2008) 201-215. [ Links ]

Grande, D., Almaguer, J., Herrera, C., Lozada, H., Rivera, J., Mal donado, M., Nahed, J. and Pérez, G.F. 2006. Los árboles de los sistemas silvopastoriles de la Región de la Sierra de Tabasco y la presencia de epifitas. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 209-212. [ Links ]

Hermosillo, Y., Aguirre, J., Alonso, R., Gómez, A., Jacobo, R. and Ramos, A. 2008. Combinación de métodos para germinación y emergencia de germoplasma forrajero en la obtención de planta para sistema silvopastoril en Nayarit. In: IV Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. "Estrategias ambientalmente amigables". Experiencias productivas y académicas. Universidad de Colima. Colima, México. May 12-16. pp. 133-136. [ Links ]

Holguín, V.A. and Ibrahim, M. 2004. Bancos de forraje. Enfoques silvopastoriles integrados para el manejo de ecosistemas. CATIE (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza), Costa Rica. 22 pp. URL: http://www.virtualcentre.org/es/res/gef_proy/BANCOSFORRA.pdf. (accessed March 29, 2007). [ Links ]

Jiménez, G. and Hernández, J. 2001. Estrategia conjunta para la conservación de la biodiversidad, selva lacandona Siglo XXI. Taller Sustentabilidad de Actividades Agropecuarias, Forestales y Pesqueras. 87 p. [ Links ]

Ku, V.J.C., Ramírez, A.L., Jiménez, F.G., Alayón, J.A., Ramírez, C.L. 1998. Árboles y arbustos para la producción animal en el trópico mexicano. In: Memorias de la conferencia electrónica; Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en Latinoamérica. FAO-CIPAV. Cali, Colombia, URL: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAP/frg/AGROFOR1/bnvdes23.htm. (accessed May 15, 2008). pp. 161-180. [ Links ]

Leyva, B.V. 2003. Estudio morfométrico, análisis radiológico y germinación del árbol del Guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.). Tesis de Licenciatura. Instituto Tecnológico Agropecuario No. 18. Úrsulo Galván, Veracruz, México. 46 p. [ Links ]

Leyva, B.V. 2006. Uso, extracción y manejo de los acahuales de la Selva Baja Caducifolia en las localidades Acazónica y Paso de Ovejas de la zona sotavento del estado Veracruz. Tesis de Maestría. Colegio de Posgraduados, Campus Veracruz. Veracruz, México. 116 p. [ Links ]

Lizárraga, S.H., Solorio, S.F.J. and Sandoval, C.C.A. 2001. Evaluación agronómica de especies arbóreas para la producción de forraje en la Península de Yucatán. Livestock Research for Rural Development. URL: http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd13/6/liza136.htm) (accessed May 27, 2006). 13:1-12. [ Links ]

López, M.D., Soto, P.L., Jiménez, F.G. and Hernández, D.S. 2003. Relaciones alométricas para la predicción de biomasa forrajera y leña de Acacia pennatula y Guazuma ulmifolia en dos comunidades del Norte de Chiapas, México. Interciencia. 28:334-339. [ Links ]

López, J., Tejeda, I., Vásquez, C., De Dios, G.J. and Shimada, A. 2004. Condensed tannins in humid tropical activity: Part 1. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 84:291-294. [ Links ]

López, O.S., Villarruel, F.M., Ortega, J.E. and Ruiz, E. 2006. Crecimiento y producción de Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. en bancos de forraje bajo condiciones de clima cálido subhúmedo. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 133-138. [ Links ]

López, H.V.M. 2008. Composición química y consumo voluntario de Guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia) y pasto Taiwán (Pennisetun purpureum) por ovinos tropicales. Tesis de licenciatura. Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Guerrero, México. 63 p. [ Links ]

López, H.M.A., Rivera, L.J.A., Reyes, O.R., Escobedo, M.J.G., Magaña, M.M.A., García, R.S. and Sierra, V.A.C. 2008. Contenido nutritivo y factores antinutricionales de plantas nativas forrajeras del norte de Quintana Roo. Técnica Pecuaria en México. 46:205-215. [ Links ]

Manríquez, M.L.Y. 2010. Establecimiento, calidad del forraje y productividad de un sistema silvopastoril intensivo bajo pastoreo de bovinos y ovinos en el trópico sub-húmedo. Tesis Doctoral. Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Veracruz. Veracruz, México. 89 p. [ Links ]

Manríquez, M.L.Y., Calderón, Z.M., Lara, B.J., López, O.S. and Villarruel, F.M. 2007. Potencial de Guácimo como forraje en Veracruz. Aspectos técnicos y financieros de la propagación del árbol forrajero guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.). Agroentorno. 87:27-28. [ Links ]

Martinez, T. 2006. Una Planta Mexicana derrota a la Diabetes. Impacto (Diciembre). 27-29. [ Links ]

Medina, J.M. 1994. Observaciones sobre el consumo de guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia), tigüilote (Cordia dentata) y pasto guinea (Panicum maximum) por cabras semi-estabuladas. In: Benavides, J.E. (ed.). Árboles y Arbustos Forrajeros en América Central, Vol. 1, CATIE (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza), Costa Rica. pp. 249-256. [ Links ]

Navas, A., Restrepo, C. and Jiménez, G. 1999. Funcionamiento ruminal de animales suplementados con frutos de Pithecellobium saman In: IV Seminario Internacional sobre sistemas agropecuarios sostenibles CORPOICA. Cali, Colombia. Octubre-30. pp. 283-284. [ Links ]

Nieto, M.J., Manríquez, M.L.Y., López, O.S. and Gallardo, L.F. 2006. Guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.): Una opción para la producción de forraje en la ganadería del sistema terrestre de lomeríos, en el centro de Veracruz. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 139-143. [ Links ]

Ortega, V.E. 2009. Efecto de podas estratégicas en Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. sobre la producción de forraje en la época seca. Tesis de licenciatura. Instituto Tecnológico de Huejutla. Huejutla, Hidalgo. 71 p. [ Links ]

Palma, J.M. and Román, L. 2003. Frutos de especies arbóreas leguminosas y no leguminosas para alimentación de rumiantes. In: II Conferencia Electrónica sobre Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en América Latina. Depósito de documentos de la FAO. URL: ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/005/y4435s/y4435s00.pdf (accessed May 27, 2008). pp. 271-281. [ Links ]

Pérez, L.E., Nazar, B.H. and Pérez, L.Y. 2006. Comportamiento etológico de bovinos en pastoreo intensivo en monocultivo vs. silvopastoreo, Chiapas, México. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 190-198. [ Links ]

Pinto, R., Gómez, H., Martínez, B., Hernández, A., Medina, F., Ortega, L. and Ramírez, L. 2004. Especies forrajeras utilizadas bajo silvopastoreo en el centro de Chiapas. Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria. 8:53-67. [ Links ]

Reyes, M.F. 2006. Producción de biomasa y valoración nutritiva del follaje de arbóreas en la región de la Sierra, Tabasco. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 129-132. [ Links ]

Sánchez, J.A., Muñoz, B.C. and Montejo, L. 2004. Invigoration of pioneer tree seeds using prehydration treatments. Seed Science and Technology. 32:355-363. [ Links ]

Scull, I. 2004. Metodología para la determinación de taninos en forrajes de plantas tropicales, con potencialidades de uso en la alimentación animal. Tesis de Maestría. Instituto de Ciencia Animal. La Habana, Cuba. 80 p. [ Links ]

Soca, M. 2004. Efecto del consumo de plantas arbóreas en la incidencia parasitaria gastrointestinal en pequeños rumiantes. In: Borroto, Á., Solís, J. and Díaz, J.R. (eds.). Sistemas de Alimentación Sostenible para Ovinos y Caprinos (Memorias del Curso-Taller Iberoamericano). Ciego de Ávila, Cuba. pp. 219-231. [ Links ]

Sosa, R.R., Pérez, R.D., Ortega, R.L. and Zapata, B.G. 2004. Evaluación del potencial forrajero de árboles y arbustos tropicales para la alimentación de ovinos. Técnica Pecuaria México. 42:129-144. [ Links ]

Tamayo, Ch.M. and Orellana, R. 2006. Establecimiento de cinco especies leñosas forrajeras. In: Memoria de la III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 313-315. [ Links ]

Torres, R.J.A., Castellanos, R.A.M., Luna, G.G., Nava, M.L.G., Quintanilla, M.A.R., Rosales, L.R., Torres, V.A. and Vargas, V.J. 2006. Los sistemas agrosilvopastoriles con ovinos en el Centro de Veracruz. III Reunión Nacional sobre Sistemas Agro y Silvopastoriles. México, D.F., July 10-12. pp. 15-22. [ Links ]

Vallejo M., Lapoyade, N. and Benavides, J. 1994. Evaluación de la aceptabilidad de forrajes arbóreos por cabras estabuladas en Puriscal, Costa Rica. In: Benavides, J.E. (ed.). Árboles y Arbustos Forrajeros en América Central. Vol. 1, CATIE (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza), Costa Rica. pp. 237-248. [ Links ]

Villa, H.A. 2009. Productividad del sistema silvopastoril con Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. y la utilización de la especie en los agroecosistemas de Angostillo. Tesis de Maestría. Colegio de Posgraduados, Campus Veracruz. Veracruz, México. 41 p. [ Links ]

Villa, H.A., Nava, T.M.E., López, O.S., Vargas, L.S., Ortega, J.E. and Gallardo, L.F. 2009. Utilización del guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.) como fuente de forraje en la ganadería bovina extensiva del trópico mexicano. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems. 10:253-261. [ Links ]

Villarruel, F.M. and Ruiz, M.E. 2004. El guázamo: una alternativa agroforestal para el trópico veracruzano. Agroentorno. 50:29-31. [ Links ]

Villarruel, F.M., López, O.S., Aguilar, P.L.A., Fernández, Q.L.M., Arce, E.L. And Pino, P.R. 2005. Establecimiento y evaluación de un rodal coetáneo de Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. en la llanura costera del Golfo sur de Veracruz. In: Memoria de la XVIII Reunión Científica Tecnológica Forestal y Agropecuaria. Boca del Río, Veracruz, México. Noviembre 17-18. 481 p. [ Links ]

Villarruel, F.M., Morales, G.N.C., López, O.S. and Santiz, G.M. 2007. Paquete tecnológico para el empleo de Guazuma ulmifolia Lam., una estrategia ecológica y productiva. XX Reunión Científica-Tecnológica Forestal y Agropecuaria Veracruz. IX Simposio Internacional y IV Congreso Nacional de Agricultura Sostenible. PP 1-5. [ Links ]

Villegas, D.G., Bolaños, M.A., Miranda, S.J.A., Sandoval, H.R. and Lizama, M.J.M. 2003. Flora Nectarífera y Polinífera en el Estado de Veracruz. SAGARPA-FUNPROVER (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación-Fundación Produce Veracruz). 2a edición. 11 p. [ Links ]

Zamora, S., García, J., Bonilla, G., Aguilar, H., Harvey, C.A. and Ibrahim, M. 2001. Uso de frutos y follaje arbóreo en la alimentación de vacunos en la época seca en Boaco, Nicaragua. Agroforestería en las Américas. 8:31-38. [ Links ]