INTRODUCTION

This work aims to analyze the effects that have the structure and culture of the new paradigm centered on the new public management in the performance of the main functions of the state. In it is proposed also providing a theoretical and methodological framework of reference that enables the analysis of the functions and institutions of public administration.

Scholars of public administration have been careful to try to distinguish the management of public organizations, against the policy design and against the state itself. The distribution and exercise of political power, for example, and the relationships they have with the establishment of accountability structures and administrative culture of the states. The new public management or management has given substantial, practical and intellectual impetus to a broad movement located outside the traditional bureaucratic model of public organization, which has been described as post-bureaucratic.

The new trend of the management of public affairs, the new public management, has been called from a movement of rediscovery that has become popular as the reinventing government movement of Osborne and Gaebler (1992, 1993). Managerialism, as it is also known to this paradigm, has acquired a strong influence on the so called new public management, which is mainly oriented towards the internal management of organizations and where the role played by public managers as leaders, is crucial.

With the implementation of the processes of new public management, organizations of the state sector innovated forms of production and distribution of public services, through mechanisms such as privatization, outsourcing, collections of duties and quotas, products and exploitations, and associations between various levels of government, various voluntary organizations and private companies. Many advocates of the new public management seem to assume that ensure and respect for traditional values of public service remains, despite substantial reforms in organization and administration, and despite the emergence of new values.

However, implementation of this paradigm in public administration, has given rise to several questions and concerns. This paper aims to review some of the concerns and questions focused mainly on the structure and the new culture of the paradigm of the new management or public administration, through critical analysis, focused on the approach of institutionalism as theoretical-methodological framework. Therefore, the research question focuses on determining what are the main effects that allow questioning the structure and the new culture of public management paradigm?

THE EMERGENCE OF A NEW PARADIGM IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION: THE NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT

In the current context of globalization of economic processes, management of public organizations has shown a depletion of theoretical and methodological, academic goals and empirical work paradigms. Non-members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries have accepted in different ways changes in the new public administration, integrated into another paradigm called new public management, which represents a paradigm shift against the classic work of Thomas Kuhn, in the scientific revolution. The current paradigm is a transformation that challenges the previous one and, eventually, replaces it.

Today, you can find more than 21 meanings of the word paradigm. The first meaning of the term is metaphysical or epistemological and has no direct relation to scientific validity. Paradigm is a universally recognized achievement, a myth, a philosophy, a textbook or a classical work, a whole tradition, a scientific achievement, an analogy, a successful metaphysical speculation ideation accepted in common, a law, a source of tools, a standard illustration, an envisioning the type of instrumentation, a package of anomalous cards, factory machine tools, a complete picture that can be viewed in two ways, a set of political institutions, a standard applied to the quasi-metaphysical , an organizing principle that can govern perceptions of themselves, a general point of epistemological and a new way of seeing something that defines a broad spectrum of reality (Masterman, 1970, pp. 61-65).

The current paradigm of new public management or new public management is an attempt to reform the bureaucratic administrations since the early eighties. It has spread through the countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The paradigm of new public management has focused on solving organizational intra problems of public organizations that may relate to styles of autocratic leadership, inefficient implementation of information technologies and telecommunications, systems inefficient production of goods and services, etc., (Klages and Hippler, 1991, p. 123).

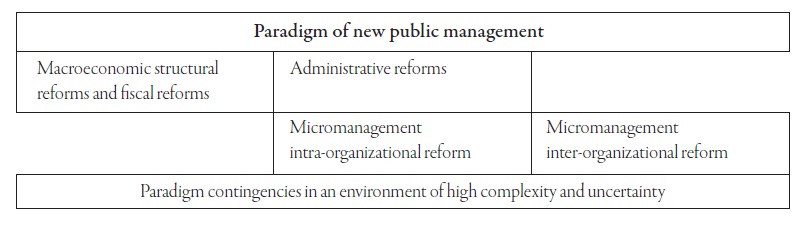

In a broader sense, the new public management is the management of public sector organizations. And it is in this sense that appear researchers like Burrel and Morgan (1979, p. 85) who argue that organizational theories lend themselves to the Kuhnian analysis, based on different schools that are happening each other, since each new theory or theoretical approach solves the anomalies left by the previous. However, other researchers, such as Bernard Séguin and Chanlat (1983, p. 33), found only two real paradigms between different theories of organization, the functionalist and critical theory. The new public management or new governance is a new paradigm based on macroeconomic and fiscal structural reforms, and makes the pair of administrative reforms.

STRUCTURAL REFORMS

In the context of the globalized economy, structural and institutional reforms of the national state have become inevitable. A wide range of structural reforms, based on the need for change in the economy, which is coupled with the processes of economic globalization, involved the application of market models and business principles to the management of public organizations. The range of structural reforms of the State, introduced by conservatives, is what has produced major changes in organizations and government functions. Many of these structural reforms are connected with the reform movement known as new public management which is based on the application of market mechanisms and business principles focused on the public sector. Structural reforms are to be the seed, under the rubric of the new public management, driving its implementation with the use of administrative techniques that are successful in the private sector.

Both proponents and critics of the new public management have lacked clarity to expose their basis. This has been repeated at the time to avoid confusion when trying to balance the new public management with structural reforms, and also when looking to make distinctions of each in terms of its main components.These components underline reducing the activities of public organizations of government through privatization processes and recruitment, the creation of new organizational forms, such as service agencies forms, strategic alliances, and the adoption and adaptation of new administrative approaches are emphasized, as empowerment.

The results of institutional structural policies explain organizational dynamics, whose significant effects include project management competence to achieve balance of members in achieving the objectives. Recent and anticipated structural reforms in the organization and management of public service seem aimed at significantly complicate ethical responsibilities. Structural reforms have resulted in the dismantling of a civil service system unified and monolithic as it became institutionalized in the 19th century, leading to develop a flexible federation of small organizational units or agencies and bureaus (Kemp, 1993, p. 8).

ADMINISTRATIVE THE BUREAUCRATIC APPARATUS OF THE NATIONAL STATE REFORMS

Using structural, behavioral, processes and socio-technical interventions technology at macro-organizational level, uses instruments and administrative, financial and human resources tools. Structural reforms, radicals of public sector organizations and computerization reforms, are motivated by the approach of reengineering business processes, and washed away by the revolution in information and communications technology (ICT).

The term information management includes five basic aspects: the introduction of technology-based message to shape and nurture the recovery process information; adjustment of information flows and relationships of information facilitating administrative processes information in organizations, as well as changes in the organizational structure, where information technology is introduced; the development of information policy, as a special area of decision making of the organization, and the use of specific experience in the field of information.

Public administration of governments has had profound reforms, including the emergence of new public management since the early sixties. Also, since the early eighties, it has driven the administrative reform called new public management, which has been implemented by member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Liberation-oriented and market-oriented management administration have emerged mainly by the close association they have with the existing global revolution in public management; a revolution encouraged by the interest in the government’s structural reforms on a large scale.

The concept of public management as a way of managing the public sector organizations, considered “facets” the activities to manage public sector organizations, at the discretion of the administrative and political practice occurs frequently in the context of administrative reforms. Academics, like politicians and bureaucrats governments consider that new public management is a different way to study and improve public organizations and public administration.

The new public management is an ideal front of the structure, processes, behaviors and functioning public administration, which is based on the globally accepted organizational elements as units of the new public management intrinsic concept. The proposal for the new public management attempts to compare existing designs with new, under the label of traditional public administration. In Table 1, the new public management and public administration are compared, since the main components to determine the instrumental nature of the new governance of the state.

TABLE 1 COMPONENTS OF THE NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION.

| Components | New public management | Traditional public administration |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Customer | Citizens and communities |

| Main media | Administration | Policy formulation |

| Characteristics of public servants | Entrepreneur (Acting) | Analyst (Thinking) |

| Values | Entrepreneurship, management freedom, flexibility, creativity, enthusiasm, decision making | Ministerial responsibility, prudential, stability, ethics, honesty, justice, transparency. |

| Vocabulary | Customer service, quality, skills, managerialism, entrepreneurship, privatization. | Public interest, democracy, social equity, due to processes. |

| Culture | Private sector, innovation, business management, accountability for results, policy-administration dichotomy. | Bureaucratic, hierarchy, functionalist, stability, continuous processes of accountability, policy-administration |

| Structures | Civil service structures as organizational units, simple and frugal government, introduction to quasi-market mechanisms, decentralization. | Civil service as an institution, large departments, large government systems, resource allocation by the central authority. |

Sources: Adapted from Klages and Hippler, 1991, p. 123

QUESTIONING CRITICISM OF THE PARADIGM OF NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT

The promoters of the paradigm of new public management announced that the paradigm of bureaucratic public administration is dead and that witnessed the birth of post-bureaucratic and postmodern paradigm. It is questioned whether the new public management is a paradigm in the sense Khunian, and the consequences it brings for the study and acquisition of knowledge in public organizations. It is also questioned whether public management is a new paradigm among other reasons because it represents the introduction of ideas in the field of private management to another field of public management, such as a transfer or loan that can be fruitful administration.

Moreover, there is also the question of paradigms leading to reflect the degree of differences between the new paradigm of public management and the old paradigm of public administration. In this regard, Kuhn says (1970, p. 299) that may represent a spurious transfer. Moe (1993, pp. 46, 48), for example, recognizes the existence of a gap between the theory of this legal paradigm and its implementation: legislators suffer more and more from so-called unwanted thought, due to their interests, make a careless and show indifference to public sector organization wording.

The analytical model used for critical analysis of the paradigm of the new management and governance is based on the theoretical and methodological foundations of institutionalism, a theory which variables organizational structure and culture are reviewed, to delineate concerns and questions of the new public management, as a universal paradigm. In Figure 1 are shown the main aspects to consider in the management or governance, as universal paradigm. They are questioning the basis of what has been dubbed the new State instrumental governance.

THE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE

The assessment of how new public management and governance skills contribute in the discretionary exercise, with regard to the results of the government, given the undoubted importance of factors such as the design of public policy, dependence on resources and organizational structures it is another existing question. Government reform and governance structure is one of the key challenges facing the role of central government in recent years.

The last decades have shown profound changes in the organizational structures of economic structures and social rights. These changes have generated high impact on increasing levels of deprivation, poverty and social exclusion. In terms of organization, there are important variables of organizational structures and strategies that are linked to the power, influence, monitoring and control. The degree of beneficial interactions resulting from the coordination of these dimensions and to combine the relations between the organization of society, the state structure and the nature and involvement of corporate and civic activities, are determining factors of the level of development.

Sources: Adapted from Klages and Hippler, 1991, p. 123; Burrel and Morgan, 1979, p. 85; Seguin Bernard and Chanlat, 1983, p. 35

FIGURE 1 NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT OR GOVERNANCE AS UNIVERSAL PARADIGM

Governance processes involve forms of social coordination among interdependent and sometimes complex relationships between different agencies are coordinated to achieve stability across a range of interests of public and private organizations (Kooiman, 1993, p. 62). However, even though their property and their origins are based firmly on an organizational sector, they share ownership of some structural elements of other organizational sectors.

The authors Billis and Glennerster (1998, p. 79) show that the organizational sectors concept is a powerful tool to explain with arguments that no sector has a monopoly of inherent structural features that are virtuous, such as ownership, organizational resources, interest groups, etc., that evoke perceptions of different states of disadvantage experienced by users of the services of such organizations as defined in financial, personal, community and social terms.

The comparative advantage or disadvantage of organizational sectors requires analyzing interactions between providers and users of different agencies. The local competitive advantage symbolizes an approach to analyze interactions between the structural elements of the agencies that influence specific responses of organizations to meet the demands of their environment and that favor their development. A structural difference is the constitution of statutory organizations; those with accountability to electorates and against private organizations that are not.

The structure of the social and governmental organization is a reflection of historical, cultural, social, political and economic processes. Around the institution of kinship, for example, they have been structured organizations and the economic, social, political and religious institutions, in the pre-state societies. The comparative institutionalism extends Weber’s thesis (1982, 1996), based on the argument of the existence of organizational dimensions, i.e. structures that establish and develop continuity capabilities and internal credibility, in relation to groups interest and external customers. The ratio of the internal structure of the state and society holds alike for organizations and society.

Public organizations exist to administer the regulations set forth in applicable laws and regulations in every element of their being, their structure, personnel consultants, budget and purpose as the product of legal authority (Fesler and Kettl, 1991, p. 9; O’Toole and Meier, 2009, p. 508).

In modern times, according to Kettl (1993, p. 55) the borders between nations are erased by the processes of economic globalization and also by changes in the processes of bureaucratic administration, to new forms of public management. It becomes more difficult to determine with certainty where the boundaries of government organizations, such as knowing where organizations and government agencies are starting, and where they end in their relationships with other organizational structures, such as contractors.

For simplicity, it is argued that there is ambiguity in organizations where interrelationships between individual and group associations are mixed. The ambiguity of the groups of interest arises and is accompanied by deep tensions resulting from the confrontation between the demands of structures of bureaucratic control of paid staff with the requirements for membership of individuals whose volunteer efforts give support to a democratic association.

Failures of individual hierarchies identified with public bureaucracies and the political market represent the critical point to finish the formality of an organizational ambiguity. However, bureaucratic organizational structures are less ambiguous, usually subject to accountability and transparency of actions, which are not necessarily effective in the delivery of human services and satisfaction of individual and collective needs. There are many concepts and definitions of accountability and transparency among scientists of economics, political science, financial accounting, management science, international organizations, etc. The debate on the conceptualization and definition of transparency and accountability has resulted in a proliferation of meanings and concepts (Lindberg, 2009, p. 8; Stirton, Lindsay and Martin Lodge, 2001, p. 482).

The concept of responsibility in public management refers to the capacity, accountability and obligation. Responsibility is the ability to act with the authority of a public service and performance of its duties and obligations under the regulations. Accountability is the obligation of officials and public servants to provide information, justifications and explanations to other authorities and the general public for the performance of their duties. Responsibility as an obligation to assume the consequences of actions arising from the exercise of State authority (Hogwood, 1999, p. 23; Caiden, 1989, p. 34).

The structures of bureaucratic governments are set up with the support of new management techniques, with the systems support of internal and external communication and innovation processes directed to develop new organizational forms. Governance structures of states change, but nation states continue to control significant resources that enable them to influence, to varying degrees, the results of policies. The resources available to the different actors can be determined and organizationally structured in accordance with the form and intent of the exercise of power, which defines how these resources should be used to achieve the goals.

On the other side, Cerny (1990, p. 138) argues that the role of state actors changes by critically location with the growing structured and penetrated action of transnational organizations field. These interrelationships currently increase the impact of the state structure in complex ways that exist between the state and transnational organizations.

The theoretical approach to the analysis of public organizations is exemplified by Rosenthal (1982, p. 112) and Kelman (1990, p. 76), who analyze how policies affect organizational structures and organizational and administrative performance. Shared participation of worker’s organizations, citizens, residents, civil, etc. and other organizations such as state agencies, create possibilities for local social classes and specifically local interest groups organized along the lines that are defined by the division of labor. Lynn reference (1996a, p. 104) is required in the context of virtually every significant issue on the agenda for public and political decision involving institutional and structural issues (Lynn, 1996b, p 105; 1997, p. 38).

Economic change protects the new institutional arrangements under the regulations of the State, on the mass public, because the construction of new institutional forms and organizational arrangements make possible the realization of powers that go from the bottom up in the power structure of organizations public, which are difficult to understand for the popular classes. An institutional arrangement represents an established order with a pattern of interest and a distribution of value among different stakeholders.

Derived from the principal-agent theory, the theory of implicit contracts and the economy of transaction costs add conceptual subtleties to the relationship between strategy and market structure. Organizational leadership and administrative strategies are therefore endogenous phenomena against the theory of the firm, within its organizational, industrial and market structures because the facts relate to the firm and industry market, therefore, they are predicting the management strategies of the firm. Institutional structures that are responsible for the implementation of public policies can be outsourced in different and separate organizations.

The formal structures of organizations correspond to what should be named as the concrete expression of public policy, including goals of legislated objectives, offices and agencies with assigned duties: organizations, policy design, budgeting and financial arrangements and accounting. The theoretical approach of Rosenthal (1982) and Kelman (1990) as researchers from the communities of public policies, provide the basis for institutional and organizational analysis of policies and structures that affect the administrative and organizational performance.

There are an infinite number of ways in which these structural dimensions can be put together in organizations, but while all bureaucracies together are different, there are also similar bureaucracies, each with different basic organizational structures. Table 2 shows the four basic structures of public organization that are evident. It is noted that the structure can be placed in public organization and there is, in fact, few basic types of structural configuration, each of which has considerable potential for detailed variations.

In this sense, organizational configurations are structured according to routine processes for the offering of specific services. The administration may be a separate and distinct functional organization and share the same structures that have operational areas. In social theory the concept of organizational field originates from which the processes of bureaucratization and other forms of change occur (DiMaggio and Powell, 1991, p. 64) as a result of the processes that make similar records without necessarily become more efficient. This is because it is assumed that the definition of structural field is recognized as a task of institutional life, as in regulatory agencies. Once the organizational field identifies the forces that govern change and, in particular, what is the organizational isomorphism, these forces are easily identified.

Claiming autonomy by bureaucratic structures for the exclusive exercise of administrative functions and management, it is based on the professionalism of the administrative capacities of different political structures. Under the new approach to governance, these are characterized by their organizational units are designed with small and simple structures, instead of complex systems of large structures, which are aimed at delivering services to citizens.

TABLE 2 FOUR BASIC ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES

| Structure | Characteristics | Opportunity |

|---|---|---|

| Bureaucratic | Small mechanical variety of specialists | Great demand for services |

| Mechanic | Generalists and administrators | Standardized services |

| Highly centralized | Economies of scale | |

| Positional Authority | Simple technologies | |

| Leader set highly stratified | ||

| Clear rules and responsibilities | ||

| High formalization | ||

| Professional organic | Wide range of specialization | Small demand |

| Professionals as administrators | Non-standard services | |

| Highly decentralized | No economies of scale | |

| Authority often based on skills | Complex technologies | |

| Changing leadership | High quality | |

| Highly egalitarian | Adaptable to changing conditions | |

| Low formalization | ||

| Roles and responsibilities are not defined | ||

| Traditional handicrafts | Artisan and semiprofessional skills | Local demand moderate |

| Centralized but work autonomy | Partially standardized services | |

| Often dominated by the founder | There are no economies of scale | |

| Small administrative component | Simple technologies | |

| Low formalization | Easy to start | |

| Size reduced | Adapted to local needs | |

| Mechanical-organic mixed | Engineers and specialists | Demand moderate to large |

| Professional field agents | Multiple products of the same technology | |

| Centralized and decentralized | Scale economics | |

| Big size | Complex technologies | |

| Some components mechanically Structured and unstructured some organically | Diversification as a strategy | |

| Sophisticated technology | Productive and adaptable | |

| Capital intensive | High startup costs | |

| Domination by committees | Potential conflicts of value |

Sources: Adapted from Hage and Finsterbusch, 1987, p. 56.

The decentralized organization structure defines new roles and relationships between state structures and local organizations and institutions. Organizations with centralized structures exert greater control over resources, although not necessarily more efficiently, allocate and redistribute these same resources. The concept of decentralization processes, as intermediate processes for creating a new order and a new state structure presupposes a redistribution of functions that facilitate the efficiency of collective action and the democratic effectiveness of societies and communities where they develop.

The trend of decentralization of structures and processes of programs and budgets in public organizations has one of the highest priorities in most public sector organizations, at different levels of government. The trend of public organizations decentralizing without departing from the existing structure of the state, confuse decentralization processes with the processes of disintegration of the unitary organization. This confusion is because it is used as a parameter for differentiation not so much the intensity of the territorial distribution of state functions but the final results of the processes and motivations that encouraged these processes.

By contrast, in systems with federalized structures or confederated organizations, local organizations exercise all functions not delegated to the federal level. Public organizations, tending to be postmodern, are characterized by flatter management structures, closely related to its objectives, which become clearer.

Under certain circumstances, exchange relationships can be governed by reciprocity and collaboration in the structures of networks, rather than complete and incomplete or implicit contracts or formal authority structures. However, organizational operations are structured into networks of relationships defined by legal obligations, moral, demands and pressures of the hosts of other actors, especially delimited by elected legislatures and chief executives. Powell (1990, p. 326-327) adds more subtlety to organizational analysis, when elucidates the conditions that give rise to the structural forms of organizational networks.

Theorists not Weberians did a combination of rules and connections of the interrelationships between individuals as the constituent foundations of structures and behaviors of non-bureaucratic organizations, bureaucratic workings and relationships between different institutional settings.

The public sector bureaucracy, articulated in administrative structure, is involved in a particular socio-economic and political system. A structure of representative bureaucracy can articulate, weigh and evaluate better the concerns resulting from the implementation of social policies for the delivery of social services for citizens. Bureaucrats, employees working within the structures of government and employees working within the organizational structure of the supplier contractor are responsible, such as servers, to promote the delivery of quality services, with quality services facing the citizenship.

The organizational approach of the public sector and government of Heymann (1987, p. 81) emphasizes the terms and implications of values and the creation of purposes, which is not limited to the few individuals or managers located at the top of the cusps of the administrative structures of public organizations. It is recognized that public managers of different levels in the structure of an administrative agency, working through collective processes. Organizational structures are more visible and consequential in the agencies and offices designated as agents of the electorate, to pursue public purposes for which they are created.

However, the new ideological developments have weakened the elements and central instruments of the structures of bureaucratic organization of the welfare state (Arellano, Gil Ramirez and Rojano, 2000, p 39; Guerrero, 2003, p. 51). Confidence in State action is destroyed by the insistence in argue that bureaucratic organizations are inevitably self-interested, as well as being instruments that are not legally responsible, efficient and effective.

The development of new types of human service, to meet new individual, social and community needs, in terms of providing services to other organizations; ways to establish contacts and connections between the various organizations; the creation and development of structures of representation of minority interests and direct services, etc., these are only a few important factors to analyze under the focus of organizational sectors. International humanitarian service organizations are usually aimed at achievement of performance results of the members, despite its rigid bureaucratic structures and in many cases, inefficient.

The term human volunteer service is neutral between different organizational sec- tors that can provide it, either in the private sector, the public sector, the social sector or by private for-profit organizations and utilities. Organizations of the nonprofit sector defined in its organizational structure and operation, identified by Salamon and Anheir (1997, p. 203) and Johnson (1997, p 559.) under four distinguishing characteristics: 1) private in the sense of being institutionally separate from government, 2) nonprofit distribution systems 3) self-governing and 4) voluntary, because there must be some degree of autonomous participation of citizens and communities.

The voluntary sector organizations includes macro agents that establish patterns of structures and behaviors, in the constitution of organizational field, as well as volunteer agents in the space and context of localities, they manifest themselves as organizations that deliver social welfare benefits to individuals and communities.

A comparative advantage of voluntary sector organizations over other types of organizations and public agencies, are their hybrid structures with certain distinctive ambiguities that facilitate the solution of problems emerging from the gap between the principal-agent relationships with his lack of interest in the market (Billis and Glennerster, 1998, p. 79). Essentially, it holds that if the ambiguity of the stakeholders, resulting from organizational growth is decreased, the comparative advantages of voluntary agencies tend to fall.

Voluntary sector organizations are deeply rooted in the structure of social services and human well-being, rather than public organizations, whether considered as an issue of organizational effectiveness. With regard to the effectiveness of the voluntary sector organizations on organizations and public agencies, purely economist approaches, from the supply of services, tend to simplify organizational structures care agencies and voluntary organizations, without necessarily being their processes more effective, due to ambiguous and complex situations.

Organizational failures occur at all levels of the organizational structure of government, because it fails to recognize the fallacy of bureaucratic structures and organizational machines. Finally, Moe and Gilmour (1995, p. 136) argue that accountability, such as politics, necessarily assumes hierarchical structures based on legality.

THE NEW CULTURE OF PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS

Culturalist approaches to modernization theories, dependency theories and theories of system-world insist on a perverse exploitation, where the state is inherently the problem rather than the solution. The emergence of efficient, responsible and constructive organizations rather inefficient, irresponsible and destructive organizations are the result of certain institutional and cultural conditions. This approach is the antecedent of the study subsequently embodied in the capital that relate as a moral resource, based on trust or as a cultural resource that defines the boundaries of the action and the particular status of individuals and their interactions, in different groups and organizations.

The concept of culture relates the values, traditions, customs, ideas, etc., which they are based on the best management practices of organizations. The administrative culture is constituted by the body of knowledge, attitudes and skills of those who exercise authority (Waldo, 1965, p. 91) in public organizations. It is important to distinguish, in the debate, the conceptualization of the administrative culture regarding organizational or corporate culture. The administrative culture is a powerful leadership tool, because it consists of the values, beliefs and norms that influence the behavior of people. Corporate culture is one of the variables that the new public management has borrowed conceptually, anthropology and to develop as an administrative tool, has become an important element of the new public management.

Public organizations develop value statements as an organizational philosophy and as the fundamentals of organizational culture, which serve as a framework for the effective administration seeking to achieve high performance. Since the mid-eighties, The D’Avignon Committee, in Canada, concluded that public organizations should have a coherent management philosophy clearly expressed in the organizational culture, in the form of a creed based on the principles, values and attitudes corporate governance, which is the foundation upon which management practices and administrative systems are erected.

The new public management proposes the management of organizational culture and values as a management tool the same way as other resources of organizations managed (Garcia, 2007, p. 43). This argument is widespread and has been accepted by the public organizations at all levels of government. In this framework, the core values of the new culture of public organizations, with lifelong learning, outsourcing, experimentation, adaptability, absorption of uncertainty, innovation, benchmarking, will emphasize the focus on customer needs, entrepreneurship, risk taking, etc.

Under the approach of managerialism, administrators as managers use a cultural construct to provide for their approach to welfare service, customer-centric. The new public management assumes widely, a culture of honesty in public service as essential. Conclusive research on the culture of the organizations highlighted as finding, the importance of ethical values such as integrity, accountability, justice and equity. In addition, these values are not present only in the list of traditional conditions but also nested among the most important current values of public organizations, federal and local spheres of government. The practice of this administrative culture is expressed in the code of good administrative practices, which contains principles to be applied to public organizations, institutionalization processes, governance, transparency, access to information, accountability, etc.

However, it is sometimes argued that values innovation are not, in essence, actual values, or so, to the best result of second order but not instrumental. That is, the media are thus offering important ends. These values are described as the bedrock of organizational cultures.

Research properly constructed consists of evaluation of explanatory and comparative reference frameworks, test models focused on structures / cultures / organizations / spatial contexts and comparison of different instruments to achieve the same comparative and checking results. In addition, the new public management in government organizations takes into account the organizational culture of the private sector and accountability for results, rather than the traditional public sector as well as the processes of accountability and vocabulary, efficiency and the service rather than justice of the public interest.

Public organizations develop, select and maintain value statements to develop an organizational culture that provide the instruments to achieve government objectives through interventions that affect cultural change. Organizational culture, also called corporate, confers legitimacy on organizational structures and social controls and social sanctions that value exercise behavior in organizational and individual levels (Lachman and Hinings, 1994, p. 52). The questioning of the functions and activities of organizations and their results reflect significantly, a change in organizational culture. The pursuits of appropriate values in organizations affect cultural change and thus, restructuring considered by scholars and practitioners as a form of organizational transformation.

If the culture of a public organization or public service as a whole is characterized by the strength of shared values, there should be less need for rules of conduct. Modeling and quality of leadership roles have a tremendous impact on organizational culture and individual behavior, because it is only through leadership that values public servants in office can be put into action and promote a wide range of public service values.

The elements of operational departments, particularly the human resources regime are carefully appointed, designed and implemented, and care is defined in the organizational design to support and strengthen the culture of public service in the new agencies. However, by the fact that organizational cultures in public service work in particular, central government agencies cannot succeed in promoting ethical values through service, without the support of individual departments and agencies.

The diversity of organizational forms and cultures are essential elements of the public service, vital to the performance of particular programs and services, but above the values of individual organizations, there are values that belong to all public servants and they are supported by systems or policies that support unity and mobility in the public service. Policies on systems that lead to excessive fragmentation or a series of ghettoes of employment would be strong support for the values of public service and the foundation for a broad culture of public service. There is a great exchange between the sectors with more short-term contracts that cannot be assumed in the public service as everyone, because not assimilate a culture of public service unless they are told what is expected of them and reinforce this message systematically.

The approach based on the core values for organizational cultures provide the foundation of an analytical framework to explain the evolution of the practice of public management. Effective management of these values representing organizational cultures contributes to achieving the goals of the organizations. However, it is accepted that an organization or public agency achieves objectives, regardless of the various political environments and the various organizational cultures that require specific adaptation to specific programs to the particularities of each situation.

The processes of legitimation of public organizations do not always have the appropriate organizational structures, organizational systems and providers to ensure the laws that legislators pass to be a democratic reflection necessarily constructed from the views of citizens. Entities that are inserted into organizations with permanent bodies of mutual defection, lead to high levels of hostility, frustration and inconvenience. These consequences are inevitable discriminatory culture products.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis of the structure and culture of the new paradigm of management or new public management, allows us to conclude that there is a conscious concern of the scope that has, so far, had in terms of its effects on the new instrumental State governance. The detailed theoretical description, supported by much practical instrumentation, realizes the journey made through a complex hybridization of the traditional model of public administration and the emerging program, under the paradigm of the new management or public management, on economic, political and social programs of the state.

From the eighties, especially the model welfare state has been the victim of a strong onslaught by the neoliberal model, resulting in what has been called “new instrumental governance”, which claims that many of the functions has developed and played by the State, such as education and health, they are transferred to the structures of market organizations or businesses for profit; and organizations of civil society with welfare functions purely altruistic and public welfare. This transfer of functions to civil society takes place after the State has neglected infrastructure and public services, under structures and new institutional and organizational cultures, which leaves many open questions.

CONCERNS AND QUESTIONS

The revision of the paradigm of new public management is carried out essentially in the methodological steps needed to question and identify the action of the state in the administration of organizations and public agencies, by applying the specific management practices, based on the theoretical and methodological framework of the new institutionalism critical criteria. Then, following are listed only some of these questions and some concerns that can be foreseen, not exhaustively, but rather as examples.

The framework of the management of public organizations is generated questioning whether this is a mixture of art, science and profession. Theoretical methodological frames of reference for organizational analysis used are complex, although allow to question whether the public management is assumed in reference to the exercise of the discretion of the actors, in their various roles and administrative functions, as in the case of first level supervisors.

If the efficiency of the private market economy is questioned, by itself, then this argument implies that private companies need a more critical and analytical differentiated approach before they are recommended as models of organizational effectiveness for public organizations. These concerns are often matched by the public interest and the interest of the current government. That is, the public interest is defined as the current government says it is. The society that is democratic worries about income disparities existing between citizens and their welfare. Therefore, it must make political decisions involving, in many cases, questionable negotiations.

From a perspective of new public management, public administration neglects real life of public organizations, because it pays close attention to administrative due process while ignoring results that truly generate a change in the actual users of public services and the quality of their interactions with government. Under these arguments, the new management or public management has little or nothing to say about the tasks required to transform public organizations.

There is a genuine concern for the application of these principles in the entrepreneurial model, from the perspective of the new public management in terms of democratic ideals, because the public entrepreneur is able to leave the self-interested, conduct in the public interest. It is concerned that the concept of public interest does not provide sufficient guidance for behaviors focused on ethics, specifically. There is concern about the urgency to have the behavior of public servants, who to pursue the public interest, may lead some of them to be injected, excessively, personal values in the processes of decision making, so that to achieve a personal benefit instead of a social benefit. Behavioral assumptions involved in the new public managerial entrepreneur are another area of concern.

Other less fundamentalist proposals in their approach question the need for organizational changes and define as essential that, in most cases, it is more appropriate to an incremental approach. Recent research in organizational reengineering processes has been critical of the theory and practice. Some of this research question reengineering from another perspective having been considered the last administrative fashion. Also it questions that reengineering is considered as a rapid technique, as opposed to a revolutionary philosophy of organizational transformation. These investigations have also pointed to conflicting messages if reengineering and practices, while considering at the same time, the size of the phenomenon, to suggest that reengineering is symptomatic of deeper problems and lacks competitiveness in the industry of advanced Western countries. This whole set of questions, and their answers practices, is all ways incomplete.

The analytical failures by the lack of care of people, in matters of design, organization and implementation of public programs, can occur in situations like organizing a public agency or create an administrative system. The action of citizens and social movements, seeking greater participation, have a voice in the decisions of the design process, formulation and implementation of public policies, question approaches on responsive customer-oriented organizations. The obligation of loyalty, at least for public servants, qualifies as an obligation to resist ministerial actions that are very questionable.

Each of these organizational and administrative changes involves issues and outlines ethical dilemmas in the application of ethical values to proposed changes in the organization and management that do not provide easy answers, especially against conflicting values and which, however, it does emphasis on public servants, to ask more about the right questions. Among the ethical issues that arise from the use of associations may be mentioned those between which a public organization can simply enter association with any business firm that suits their purposes or considerations of justice and equity. This question arises, though other firms are required to have an opportunity to compete for involvement.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)