Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.13 Tijuana ene./dic. 2022 Epub 22-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2336

Papers

Transnational Citizenship and Voting From Abroad in Mexico 2018: the Guanajuato Case in the Elections for President of the Republic and Governor

1 Universidad de Guanajuato, México, m.vilches@ugto.mx,

2 Universidad de Guanajuato, México, jesusaguilar@ugto.mx,

This paper descriptively discusses the vote of Mexicans and people born in Guanajuato, Mexico, living in the United States during the 2017-2018 electoral process. This presidential and gubernatorial election represented a substantial change in the electoral behavior of the Mexican diaspora. The phenomenon is relevant because it is the first time in the political history of this entity that people from Guanajuato living abroad were able to vote to elect a governor and senators. The analysis focuses on the concept of transnational citizenship, which involves the exercise of migrants’ political rights and their consequent impact on the reconfiguration of the State, especially at the subnational level, in addition to being an expansion of political rights that led to the implementation of a series of mechanisms by the federal and local electoral bodies to disseminate and make this right accessible.

Keywords: 1. citizenship; 2. voting from abroad; 3. subnational government; 4. electoral behavior; 5. Guanajuato; Mexico.

Se realiza un análisis descriptivo del voto de mexicanos y guanajuatenses en el extranjero durante el proceso electoral de 2017-2018. Esta elección para presidente de la república y gobernador del estado representó un cambio sustancial en el comportamiento electoral de la diáspora mexicana. El fenómeno es relevante porque es la primera vez en la historia política de esta entidad que los ciudadanos guanajuatenses en el extranjero pudieron votar para elegir al gobernador y senadores de la entidad. El análisis se enfoca desde el concepto de ciudadanía transnacional el cual implica el ejercicio de derechos políticos de migrantes y su consiguiente impacto en la reconfiguración del Estado, especialmente a nivel subnacional, además de tratarse de una expansión de derechos políticos que trajo consigo la implementación de una serie de mecanismos por parte del órgano electoral federal y local para difundir y hacer accesible este derecho.

Palabras clave: 1. ciudadanía; 2. voto en el extranjero; 3. gobierno subnacional; 4. comportamiento electoral; 5. Guanajuato; México.

Introduction

In the 2018 elections for President of the Republic in Mexico, the total number of votes cast by Mexicans residing abroad was 98 470, out of which more than 64 percent were for the Together We Will Make History (JHH, acronym in Spanish for Juntos Haremos Historia) coalition headed by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), while the specific voting for the National Regeneration Movement party [Morena, after its name in Spanish, Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional], created by AMLO, received more than 56 percent of all the votes cast from abroad for the election of the same position. This electoral participation of the Mexican diaspora is the highest recorded in the country's history, due to the concurrence of the election of other federal and state positions that also allowed the so-called migrant vote.

At the subnational level, voting from abroad reflected diverse electoral behaviors. Citizens from seven states were able to vote from abroad to elect their governors: Chiapas, Mexico City, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Morelos, Puebla and Yucatán. In the case of Guanajuato, it was the first time that extraterritorial votes could be cast to elect governor and senators.

This article analyzes the vote cast from abroad to elect president in Mexico and state governor of Guanajuato, specifically by citizens whose birthplace is Guanajuato. This case study is relevant for several reasons. In the first place, it is the first time that emigrants from Guanajuato can vote to elect their governor and senators; secondly, because Guanajuato is one of the entities with the greatest migratory dynamism in Mexico in terms of emigrants, returnees and remittances; thirdly, it was the only state in which the vote of state residents did not favor AMLO; on the contrary, with a tradition of more than 25 years of governments from the National Action Party (PAN, acronym in Spanish for Partido Acción Nacional), the majority of the votes for presidential election were for candidate Ricardo Anaya from the Mexico First (Por México al Frente) coalition, formed in turn by the PAN, the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD, acronym in Spanish for Partido de la Revolución Democrática) and the Citizen Movement Party (PMC, acronym in Spanish for Partido Movimiento Ciudadano). However, things were different for the vote to elect governor, since Ricardo Scheffield Padilla, the candidate by the Together We Will Make History coalition, made up of Morena, the Labor Party (PT, acronym in Spanish for Partido del Trabajo) and the Social Coalition Party (PES, acronym in Spanish for Partido Encuentro Social), obtained the majority of votes from abroad, more than 56 percent of all votes received from abroad (4 826).

A descriptive analysis of the vote of Guanajuato natives living abroad is hereby carried out, from the perspective of transnational citizenship (Baubök, 1994), which conceptualizes a progressive opening of nation States towards recognizing political rights beyond the concordance of the State authority, the territory, and the nation. Indeed, from the nationalist vision of citizenship, political rights are not universal for all people, but rather subject to the condition of being a citizen residing in a territory; however, a development is perceived in the expansion of the institutional recognition of political rights in different regions of the world. One of those political rights is transnational suffrage (Alarcón, 2016) and can be analyzed in three aspects: a) the vote to elect a supranational entity, b) the vote of foreign residents in internal national processes (mainly of a local nature), and c) the vote of national residents from abroad for external national processes.

This analysis addresses the last aspect of transnational voting. The specific case of the postal vote of Guanajuato natives (Guanajuatenses) living abroad for the election of State Governor and President of the Republic in the 2017-2018 electoral process. This is relevant for Mexican democracy and its possible consolidation given that the extraterritorial vote of Mexican emigrants is an indicator of the political participation of more sectors of society, by means of “a legal system implementing the rights of citizenship under conditions of equality” (Cordourier & Aguilar, 2018, p. 12).

In the first section of this work, the main contextual aspects of the emigration of Mexicans and Guanajuatenses (people born in the state of Guanajuato) abroad and their demographic and economic importance are constructed so as to understand the need to provide institutional channels for the political participation of the Mexican diaspora. In the second section, a theoretical- interpretative framework of the vote from abroad is provided, which measures the meaning of this political practice that envisions a transnational citizenship in the Mexican-American context.

In the third section, the background of the vote of Guanajuatenses abroad is provided, addressing the institutional changes at the federal and state levels to show that the institutional mechanisms have been updated through successive advances in a three decades-discussion. Finally, in the fourth section, the vote of Guanajuatenses abroad is described in terms of the number, origin, sex and age of the voters, then closing with their political party and candidate preferences.

The migration of mexicans and guanajuatenses abroad

In 2017, the number of Mexican international emigrants around the world was estimated at about 13 million, three times more than the 610 000 figure from 1990. However, almost all Mexicans residing abroad, that is, around 12 683 000 (97.83%), are located in the United States of America (Conapo, Fundación BBVA Bancomer, & BBVA Research, 2018). The other main destination countries for Mexicans are Canada (0.63%), Spain (0.38%), Germany (0.14%), and Guatemala (0.14%). This way, the importance of the Mexican diaspora in the U.S. is essential to understand the effects of extraterritorial voting in Mexico and Guanajuato.

The central Mexican state of Guanajuato is part of the traditional migratory region of the country, together with states such as Michoacán, Jalisco and Zacatecas. For over a century it has been a region from which migrants leave for the United States. The economic development of North America and its need for a workforce to build infrastructure were one of the main factors initiating this migratory dynamism. Between 1884 and 1888, the northern cities of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, and Nuevo Laredo (Tamaulipas) were connected to Mexico City by rail, linking various towns in the states of Querétaro, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosí, and Coahuila. This important means of transportation allowed Mexicans from this area to move and meet the work demand in the North, caused by the Chinese worker exclusion law from 1882. Between 1880 and 1910, the population of Mexicans in the United States went from 68 399 to 221 915 people (Durand & Arias, 2004).

The constant demand for cheap labor in the U.S. that made possible the geographical expansion of its industrialization process and consequent economic growth, as well as the corresponding supply of immigrants due to the turbulent sociopolitical context in Mexico, set the bases for the dynamic migration taking place since the end of the 19th century. The current migration system between both countries with its characteristics of unidirectionality, neighborhood and massiveness (Delgado & Márquez, 2006) has grown complex as it persists in different socio-historical contexts in the development of these two countries. Durand (2016) points out six migratory stages of this process: the hooking era (1884-1920); that of deportations and massive migrations (1921-1941); the Bracero Program (1942-1964); that of undocumented migration (1965-1986); the great split era: from amnesty to harassment (1987-2007), and the battle for immigration reform (2007-2014).

This historic intensity of Mexican migration to the United States explains that in 2010 the Pew Hispanic Center estimated that 33.7 million people of Mexican origin lived on United States soil, of which 22.3 million were born in that country, but said they were of Mexican origin, and 11.4 million were born in Mexico (Vega-Macías, 2015). Thus, of the estimated 11.4 to 12.2 million Mexican immigrants currently residing in the U.S., over one million (1 011 000) were born in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico.1 According to the number of consular registrations, in 2015 the main states of residence of Guanajuato natives in the U.S. were the states of Texas, California, Illinois, North Carolina and Georgia. While the main municipalities of birth where the Guanajuato migrants came from were León, Celaya, Irapuato, Acámbaro and Pénjamo (Conapo, Fundación BBVA Bancomer, & BBVA Research, 2017).

The irregular status of Mexicans residing in the U.S. has been decreasing since 2007, the year in which it reached a historical maximum of about 7 million people who did not have a permit to legally reside in the United States. Yet from 2011 to 2016, the Pew Research Center estimated that the undocumented Mexican population remained stable, ranging between 5.9 and 5.7 million people, thus representing the majority (51%) of the total unauthorized migrant population from Mexico in that country (Conapo, Fundación BBVA Bancomer, & BBVA Research, 2018).

There has been, however, a change in the migratory pattern between Mexico and the U.S. due to multiple factors such as the 2008 real estate economic crisis, the restrictive immigration control policies implemented in the U.S., the decrease in irregular migration, the deportations and voluntary returns to Mexico, the increase in educational opportunities, as well as a relative increase in the quality of life in Mexico (Alarcón, 2012). Indeed, the year 2010 is perceived as a historical turning point due to the onset of zero migration, meaning the balance between the entry of mainly undocumented migrants to the U.S. and the number of deportees and returnees (García, 2012).

In 2007, the historical maximum recorded number of Mexicans living and working in the United States was reached at 12.6 million people, and year after year the population of Mexicans has been decreasing until reaching the current estimate of 11.6 million (Zong, Batalova, & Hallock, 2018).

The annual average of the migration flow from Mexico to the U.S. in the period from 2010 to 2017 has contracted to 135 000 people, reaching historical lows. According to the National Population Council (Conapo, Fundación BBVA Bancomer, & BBVA Research, 2017) in the case of Guanajuato, in the period from 2009 to 2014 (66 001) there was a decrease in international emigrants of more than 50 percent (76 690 people) compared to the period from 2005 to 2009 (142 691).

The migratory dynamism of Guanajuatenses abroad has its most relevant argument in the economic dimension, through the remittances (money transfers) that they make to their families. According to the Migration and Remittances Yearbooks (Conapo, Fundación BBVA Bancomer, & BBVA Research, 2016, 2017, 2018), Guanajuato remained in third place from 2015 to 2017 - only below Michoacán and Jalisco- in the list of entities sending the more remittances to Mexico from abroad. In 2015, 2 262 million dollars were received; in 2016 the figure increased to 2 414 million dollars, and in 2017 the figure of 2 559 million dollars was reached.

While the municipality of León, Guanajuato, was in 2017 the eighth place of municipalities in Mexico receiving the most remittances, reaching the figure of more than 253 million dollars for remittances from abroad. The first places were municipalities such as Puebla (411 million dollars), Tijuana (401 million dollars) and Guadalajara (374 million dollars). The debate on the impact of remittances on the families, communities and municipalities that receive them is still open and transcends the scope of this article as it entails multiple aspects, among which family dynamics (Lamy & Rodríguez, 2011), the impact on poverty (Aboites, Verduzco, & Martínez, 2007) and the implications for development (Canales, 2006) stand out, without forgetting the political dimension, when linked to public policies, development models and migrant associations (García, 2007).

Indeed, the power and presence of Guanajuato migrants abroad can be seen in the creation of clubs, associations, houses, federations and confederations of Guanajuato migrants. By 2019, there were between 100 and 360 associations of Guanajuato migrants abroad, almost all of them in the United States.2 There are eight federations and one confederation of Guanajuatenses. These types of organizations where first established in the decade of 1990, made up of citizens residing permanently in the U.S. and who share common origin in Guanajuato, aimed at maximizing resources for the benefit of migrants and their families (Vega Briones & González Galbán, 2009). Currently, these associations maintain relationships with the recently created Secretariat for Migrants and International Liaison of Guanajuato (Secretaría del Migrante y Enlace Internacional en Guanajuato), and with their communities of origin in an intense cultural, economic and political connection.

This set of elements contextualizes our object of study, so as to understand the importance of exercising a political right such as voting from abroad to elect authorities in Mexico. Considering that “seven out of ten Mexican migrants are not U.S. citizens” (Conapo, Fundación BBVA Bancomer, & BBVA Research, 2017, p. 41), it turns out that for more than 8 million Mexicans residing in the U.S., this is the only option to exercise a political right, namely, sending their vote remotely to elect authorities in their country and state of origin. It must be remembered that there also is a large contingent of Mexicans who may have dual citizenship; although there are no precise figures, it is estimated that between 20 and 22 million people reside in the U.S. and could exercise the right to extraterritorial suffrage to elect authorities in Mexico (Rojas Choza & Vilches Hinojosa, 2017). Therefore, this issue makes us face the problem that a person can participate in the public affairs of two different States, something that we have framed as transnational citizenship.

The transnational citizenship of mexican and guanajuatense migrants

In its relation to migration, the concept of citizenship has been widely debated in the specialized literature on the subject. In times of globalization, Western democracies are facing the expansion of the notion of citizen. In the Anglo-Saxon context, Joppke (2010) criticizes the emergence of a light citizenship in the migrant destination countries, where easy access to rights and minimal obligations of individuals with thin and interchangeable identities due to ethnic diversity are favored. In Mexico, Mateos (2015) draws attention to the impact of multiple citizenship practices (one individual having more than one citizenship) not only on destination countries, but also on the very conception of the nation State system, and how this process represents a strategy that opposes the increase in restrictive immigration policies.

These theoretical developments are in part an explanatory reaction to the consequences of complex practices across borders. The effects were felt on the liberal vision of citizenship conceptualized in the twentieth century in England by Thomas H. Marshall (1997). From this perspective, individuals are granted an equal status by belonging to “a” political community, as members with full civil, political and social rights. Indeed, for Marshall, citizenship consists of three elements: 1) the civil element, which consists of the rights to exercise individual freedom, 2) the political element, which refers to the right to participate in the exercise of political power, and

3) the social element, which consists of the right to security, economic well-being, education and social services.

Mobility across borders, as well as the sociopolitical belonging of migrants, does not correspond to the category of full exclusive member of a single nation State. On the contrary, international migrants belong to at least two States (simultaneously, through information technology and in a circular way if economic, political and border conditions allow for it), while access to rights is limited, progressive, and in most cases, incomplete: even when naturalized, migrants are often excluded from the functions considered most important in a country, for example, they cannot be elected to high positions of popular election. Together with other contemporary social processes, international migration calls into question two central assumptions of the classical theory of citizenship: the congruence between nation, territory and State authority; and the homogeneity of the population in terms of characteristics such as class and nation (Faist, 2015).

Therefore, theorizing on the problems of citizenship and extraterritorial suffrage becomes relevant in this era of migration. Beyond the classical liberal vision, the concept of transnational citizenship is proposed, which criticizes the essentialist vision of nation and community, wherein original belonging to a community or a people is not the fundamental criterion for a person to enjoy full rights, but rather acknowledges a transnational dynamic of action across national borders as part of the daily life of migrants.

In order to focus on the process of transnationalization of citizenship, it becomes necessary to recognize that in the social world of the 21st century there are social spaces between nation States, and that these serve as scenarios for the “emergence of relatively long-lasting and solid cross- border national, State, and multi-local relations of social practices, systems and symbolic artifacts that grow broad and deep” (Pries, 2017). These social, cultural, economic and political interactions take place across borders above and below interstate relations at a level of global intensity never before seen in the history of mankind, due to the revolution that the new technological paradigm has brought about (Castells, 2002).

From this perspective, transnational citizenship (Vilches, 2017) is a simultaneous way of belonging to more than one political community in a new social space between several countries, which implies cross-border practices of public life participation that reinforce relations between individuals and communities. Therefore, transnational citizenship can be seen from a double perspective. The first perspective is a legal-political vision; in this sense, transnational citizenship is defined by the set of rights recognized by two or more countries to an individual for being territorially or extraterritorially linked to the nation, people or community that each of the two States represents. The second perspective relates to the facticity of the migrant's activities, that is, to concrete civil and political practices. From this point of view, transnational citizenship is the set of actions that an individual carries out in two or more countries simultaneously and that have consequences for the exercise of civil and political rights in a transnational space, which in turn implies generating consequences within the countries to which they are linked.

This work focuses on the first perspective of transnational citizenship (the legal-political vision), specifically on the right to vote from abroad. Attention should be drawn to the fact that exercising this right is materializing one of several political rights.

Political rights are faculties that enable the participation of citizens in public decision-making. Fix-Fierro (2006) classifies the political rights of Mexican citizens in three dimensions. The first refers to the active vote, that is, to the power to express a political preference, be it that of a candidate for the election of a position or to approve or reject any law or public policy. The second dimension refers to the passive vote, that is, to a citizen's condition of being likely to be elected or appointed to public office. The third dimension of political rights is the one related to political association, which implies the possibility of citizens to organize themselves with others and being able to actively participate in the public affairs of a political community, for example, to be members of political parties.

From the legal point of view, article 35 of the Mexican Constitution sets forth eight rights of Mexican citizens: 1) to vote in popular elections; 2) to be able to be voted under conditions of parity; 3) to associate individually, freely and peacefully to partake of the political affairs of the country; 4) to take up arms in the armed forces; 5) to exercise the right to petition in all kinds of businesses; 6) to be able to be appointed to any public service job or commission; 7) to propose bills through authorized procedures, and 8) to vote in popular consultations.

The recognition of these citizen rights promotes citizen inclusion in modern democracies under conditions of equality in the civil, political and social spheres, while opening the possibility of demanding responsibilities from appointed officials. Particularly so in Mexico, the recognition of the right to vote from abroad takes on special importance for the largest migratory diaspora in the world in a single country (more than 12 million Mexicans live and work in the U.S.), and is part of the political rights of Mexicans abroad (Durand & Schiavon, 2014). It must be taken into account that Mexicans residing abroad have demanded the right to vote since the beginning of the 20th century, and so this is not a sort of graceful concession, but rather a social demand of migrant groups that in our context become powerful transnational actors.

From the perspective of the transnational citizenship of migrants, the extraterritorial suffrage of Mexicans abroad is a way of expressing a deterritorialized citizenship, which crystallizes a legal- formal practice that in turn links cross-border spaces, institutions, groups and norms, making it possible to influence the political conformation of the State and that which is national.

Therefore, the extraterritorial vote is not only linked to the development of the electoral political system (Emmerich & Alarcón Olguín, 2016), but it is also linked to a series of complex processes of political participation beyond national borders, where migrant associationism, transnational protests and multiple citizenships are some of the forms that we can perceive and that are reconfiguring national and subnational States.

It is in this order of ideas that the importance for the state of Guanajuato that its emigrants can vote for the first time in history to elect governor and senators at the federal level in an election like the one in 2018, concurrent with the election of president of the republic, is better understood. Along the same line, the subnational sphere becomes relevant as a space for recognizing the political rights of one of the most influential Mexican migrant communities in terms of remittances and sociopolitical participation. Under the perspective of transnational citizenship, Guanajuato residents abroad have developed for over 100 years different forms of transnational participation, which have had an impact on the configuration of the various localities of this Mexican state’s different municipalities. Therefore, this work provides elements for the understanding of a transnational citizenship that is increasingly graspable in the state of Guanajuato, and in an expelling country like Mexico.

Background of the vote of guanajuatenses abroad

A slow but progressive expansion of the political rights of Mexicans has come to pass through the evolution of the Mexican electoral system. One of the most recent advances is allowing Mexicans abroad to exercise their vote to elect public officials in their country of origin. In Mexico, a decade passed (1996-2006) from its legal recognition until transnational suffrage became effective, while Colombia legislated in favor of its citizens voting from abroad already in 1962. Currently, sixteen Latin American countries allow their citizens residing abroad to vote (Navarro, 2017).

Table 1 summarizes the main reforms that have taken place so far to guarantee the vote abroad at the federal level, and that consequently affect the local sphere, as is the case of Guanajuato. The onset of these legal transformations was in 1996, within the framework of what was known as the “definitive political reform” (CESOP, acronym in Spanish for Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión Pública [Center for Social Studies and Public Opinion], 2004, p. 35), as the lock was eliminated to allow Mexicans voting from outside their electoral district.

Table 1 Legal reforms on nationality and voting of Mexicans abroad, in Mexico

| Year | Reformed legal instrument | Main change |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Political Constitution of the United Mexican States (CPEUM, acronym in Spanish). Article 36. Section III | Elimination of the obligation to vote in the electoral district of residence |

| Temporary Article 8 in the electoral legislation by which a commission is created to explore the implementation of the vote from abroad | The possibility of voting from abroad is opened (a commission is created to analyze the possibility). | |

| 1997 | Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. Articles 30, 32 and 37. | Changes in nationality by birth, and prohibition of deprivation of nationality to any Mexican by birth. |

| 1998 | New Law on Citizenship. | Law of non-loss of citizenship. Opening to acquire dual citizenship. |

| 2005 | Federal Code of Electoral Institutions and Procedures (COFIPE). | Regulation of the postal vote for Mexicans abroad in the Sixth Book. |

| 2014 | General Law of Electoral Institutions and Procedures (LGIPE, acronym in Spanish). Creation of the National Electoral Institute. | Relaxation of the processes for issuance of ID, electing senator and governor in the state of origin, and electronic voting. |

Source: Own elaboration with information from Beltrán (2017), Espinoza (2016), Navarro et al. (2016), CESOP (2004).

In the years 1997 and 1998 reforms were made to the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States (1917) and a law was passed that allowed Mexicans abroad to keep their citizenship, as well as guaranteed Mexicans by naturalization their right to exercise the vote. It was during the government of Vicente Fox Quesada (2000-2006) that the electoral reform was carried out so that Mexicans residing abroad could vote for president of the republic. In 2005, the Federal Code of Electoral Institutions and Procedures (COFIPE, acronym in Spanish for Código Federal de Instituciones y Procedimientos Electorales) was reformed by presidential decree, in order to allow for the implementation of the postal vote in the election for president of the republic in 2006 (Moctezuma, 2004).

Profound reforms were carried out in the Mexican electoral system in 2014, among them several that improved and further expanded the vote of Mexicans abroad: the issuance of voting cards was facilitated and voting was allowed for the election of state senators and governors (Beltrán, 2017).

Before the electoral reform of 2014 promoted the broadening of the vote of Mexicans abroad throughout the country, several states of the republic managed to allow their citizens to vote for local authorities, particularly for the election of governors, by means of local reforms. The first was the state of Michoacán, in the extraordinary election of 2007. For the 2012 election, the then Federal District -today officially called Mexico City- and the state of Chiapas, held elections where it was possible to vote from abroad. Baja California Sur and Colima followed after, in 2015, and Aguascalientes, Oaxaca and Zacatecas in 2016.

For the 2018 election, seven states, including Guanajuato, held elections allowing the vote from abroad to elect local authorities. As a consequence of the electoral reforms at the federal level, the Guanajuato Congress reformed its local constitution in 2014 (CPEG, 1917), amending particularly Article 23: “The following are prerogatives of Guanajuato citizens: (…) II. Voting in popular elections. In the case of Guanajuato citizens residing abroad, they may vote for the election of Governor of the State” (Article 23, section II, CPEUM, 1917). With this reform, the Electoral Institute of the State of Guanajuato (IEEG, acronym in Spanish for Electoral del Estado de Guanajuato) undertook a historic process so that Guanajuatenses abroad could vote to elect governor for the first time.

The 2017-2018 electoral process and the guanajuatense vote from abroad

How many Mexicans and Guanajuatenses have voted from abroad?

As shown in this article, the experiences of voting from abroad in Guanajuato are few: two federal elections for president of the republic in 2006 and 2012, and the recent federal election for president, senators and governor of the state in 2018. Even so, there is value in reviewing and analyzing the behavior of the voters. The data will be analyzed at the federal level to later address the particularities of the Guanajuato case.

The mechanism to exercise the vote from abroad entails a registration of future voters in the Nominal List of Voters Residing Abroad (LNERE, acronym in Spanish for Lista Nominal de Electores Residentes en el Extranjero); once registered they can request the sending of a ballot by postal mail. At the federal level, the volume of applications for this registry is well below the population of Mexicans residing abroad, although it has been increasing year after year. The number of applications reached 40 877 in the first experience in 2006, then reaching 59 115 in the 2012 election; for the 2018 election, the number increased almost three times compared to the 2012 election, reaching 181 873 (see Table 2). Several reasons would explain the growing interest in participating in this election, probably due to a more intense promotional campaign by the federal and local electoral bodies: mainly for the voting card issuing process through the Mexican consulates, the novelty of being able to vote for governors and senators, and the very nature of the election, through which an important political change was in sight.

The application registry allows to keep a record of basic citizen data. One of these pieces of information is the sex of the applicant. In the elections for the three levels, more men than women were registered (see Table 2), which is also reflected in the final mailing of the vote envelopes (see Table 3).

Applying to vote from abroad does not in itself represent effective electoral participation. Participation crystallizes only when the envelope with the ballot (vote envelope) is sent to the electoral authority. There is an important contrast between the requests and the sending of the vote envelopes, which has only increased in the three elections observed. A high number of requests has effectively translated into an increase in the sending of vote envelopes, but also in a high number of citizens who did not send them. The latter was particularly noticeable in the 2018 election, in which 45.65 percent of those who requested to cast their vote by mail ultimately did not send the mail-in vote envelope. Another pending task would be getting to know the reasons why many Mexicans who received the envelope at their residence address abroad so they could vote, did not complete the sending process (see Table 2).

Table 2 Mexicans residing abroad who requested their registration to LNERE in 2006, 2012 and 2018, by sex

| Election year | Requests | Sex of the citizens who registered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||

| 2006 | 40 876 | 17 622 (43%) | 23 254 (57%) |

| 2012 | 59 115 | 26 755 (45%) | 32 360 (55%) |

| 2018 | 181 873 | 80 920* (44.64%) | 100 336*(55.36%) |

*Note: Data calculated from the applications before the addendum (181 256 applications). Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE, 2006, 2012) and the National Electoral Institute (INE, 2018).

Table 3 shows the electoral participation data of Mexicans abroad. The increase in the number of votes from abroad in each election is notorious. Nuances can be found in the comparison with the requests in the last election (Table 2); the number of votes is practically half the figure of that of LNERE registration requests. The other data that draws attention is the trend since 2006 of a lower vote of women living abroad with respect to the participation percentage of men: it ranges between 43 and 47 percent (Table 3). As there is no more information regarding this point, hypotheses cannot be proposed to explain this phenomenon; what can be pointed out is that it contrasts with the electoral participation trend recorded within the country from 2003 to 2018, in which more women than men participated. Specifically, out of the total votes in the 2018 election, the percentage of women who voted was 66.2 percent, while the participation of men was 58.1 percent, a difference of 8.1 percentage points (Aguilar López, 2019). Why do women vote more in elections within the country and less than men when abroad? This difference implies a future analysis challenge.

Table 3 Mexicans residing abroad who voted for the presidential election in 2006, 2012 and 2018, by sex

| Election year | Requests | Sex of the citizens who registered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||

| 2006 | 33 111 | 14 624 (44.17%) | 18 486 (55.83%) |

| 2012 | 40 737 | 19 145 (47%) | 21 592 (53%) |

| 2018 | 98 854 | 43 278* (43.84%) | 55 430*(56.15%) |

*Note: Data calculated before the addendum (98 708 votes).

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the IFE (2006, 2012) and the INE (2018).

One of the most interesting variables in the study of extraterritorial voting is the place of origin of Mexicans who, due to different circumstances, had to exercise their vote outside their country. Table 4 concentrates the information on this participation for the 32 Mexican states and for the election of the president of the republic.

Most of the entities have shown small growth between the 2006 and 2012 elections, but then a really significant one in 2018. There is a before and after 2018. In all the cases in which there were concurrent elections, particularly to elect a governor, the voting increased noticeably; the locally- based hypothesis that the greater number of votes was due to the motivation of influencing local politics given the case of concurrent elections, apparently works even for those citizens residing outside of Mexico.

The state governor election, rather than the presidential election, implied an extra motivation for citizens to exercise their right to vote. We must also underline the work carried out by the respective Local Public Bodies (OPL, acronym in Spanish for Órganos Públicos Locales) in promoting this type of vote, although at the moment there is no further evidence of the effectiveness of their strategies. A third hypothesis is based on the political-electoral activism that the different political parties could have carried out abroad, yet since such activity is not allowed by Mexican electoral law, it is difficult to verify this proselytism (Vilches, 2019).

In the case of Guanajuato, the level of participation in the 2006 and 2012 elections practically remained the same in the first two experiences: it went from 2 059 votes in 2006 to 2 131 in 2012. But for the 2018 election, turnout doubled to 4 836 votes. Something outstanding is that in all cases the figures are low regarding the number of Guanajuatenses, since it is estimated that around 1 100 000 people born in the state of Guanajuato reside outside of Mexico. A first conclusion derived from these data is that this mechanism of political participation is used by a very low number of Guanajuatenses, which leads us to ponder what is behind the lack of interest or what the motivation that generates absenteeism is.

Along the same line, the state of Guanajuato, being one of the entities with the largest number of Mexicans residing abroad, mainly in the U.S., stands out among the most participatory entities, yet as already mentioned, not with a participation that reflects the important presence of its citizens abroad. This latter phenomenon is however not exclusive to Guanajuato but rather common to practically all Mexican states.

Table 4 Electoral participation of Mexicans abroad for the election of president of the republic, by state: 2006, 2012 and 2018

| State of birth | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2012 | 2018 | |

| Aguascalientes | 319 | 400 | 837 |

| Baja California | 1 337 | 1 566 | 1 500 |

| Baja California Sur | 51 | 101 | 146 |

| Campeche | 36 | 51 | 211 |

| Chiapas | 121 | 798 | 1 758 |

| Chihuahua | 1 004 | 295 | 584 |

| Coahuila | 465 | 248 | 105 |

| Colima | 277 | 1 430 | 2 638 |

| Distrito Federal | 5 402 | 8 077 | 21 066 |

| Durango | 473 | 522 | 1 995 |

| Guanajuato | 2 059 | 2 131 | 4 836 |

| Guerrero | 848 | 969 | 4 355 |

| Hidalgo | 514 | 631 | 2 198 |

| Jalisco | 4 182 | 4194 | 8 550 |

| Estado de México | 3 350 | 4 391 | 6 027 |

| Michoacán | 2 661 | 2 127 | 6 054 |

| Morelos | 845 | 960 | 1 850 |

| Nayarit | 348 | 314 | 982 |

| Nuevo León | 1 353 | 2 441 | 3 923 |

| Oaxaca | 700 | 770 | 4,572 |

| Puebla | 1 265 | 1 704 | 6 012 |

| Querétaro | 474 | 714 | 1 449 |

| Quintana Roo | 138 | 228 | 510 |

| San Luis Potosí | 668 | 777 | 2 230 |

| Sinaloa | 461 | 544 | 1 592 |

| Sonora | 549 | 841 | 1 292 |

| Tabasco | 121 | 174 | 662 |

| Tamaulipas | 704 | 928 | 2 101 |

| Tlaxcala | 137 | 256 | 710 |

| Veracruz | 942 | 1 179 | 4 270 |

| Yucatán | 165 | 311 | 684 |

| Zacatecas | 652 | 665 | 2 009 |

| Total | 32 621 | 40 737 | 98 708 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the IFE (2006, 2012) and the INE (2018).

Where do the votes of Guanajuatense migrants come from?

According to the information presented in Table 5, 4 830 votes were received from Guanajuatenses abroad to elect governor in 2018. Votes were received from a total of 46 countries. The U.S. is the country that accumulated the vast majority of the votes cast: 4 171 votes, representing 86.4 percent of the total. The second country was Canada, with 3.4 percent (164 votes). It worth noting that after these two countries in the American continent, the next six countries standing out for sending votes are all European. It is until the ninth place that a Latin American country appears, Chile, with just 0.5 percent of the votes (23 votes). The other neighboring country on the southern border, Guatemala, appears practically at the bottom of the list with only three votes.

Table 5 Countries of origin of the votes of Guanajuatenses abroad for the election of governor, 2018

| Country | Votes | Percentage | Country de envío | Votes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 4171 | 86.4 | China | 4 | 0.1 |

| Canada | 164 | 3.4 | Finland | 4 | 0.1 |

| Spain | 88 | 1.8 | Malaysia | 4 | 0.1 |

| Germany | 83 | 1.7 | New Zealand | 4 | 0.1 |

| France | 47 | 1 | South Korea | 3 | 0.1 |

| United Kingdom | 41 | 0.8 | Guatemala | 3 | 0.1 |

| Italy | 32 | 0.7 | Hong Kong | 3 | 0.1 |

| Netherlands | 29 | 0.6 | Iceland | 3 | 0.1 |

| Chile | 23 | 0.5 | Poland | 3 | 0.1 |

| Switzerland | 13 | 0.3 | Singapore | 3 | 0.1 |

| Belgium | 11 | 0.2 | Cuba | 2 | 0.04 |

| Australia | 9 | 0.2 | Ecuador | 2 | 0.04 |

| Colombia | 9 | 0.2 | Norway | 2 | 0.04 |

| Sweden | 8 | 0.2 | Turkey | 2 | 0.04 |

| Argentina | 7 | 0.1 | Honduras | 1 | 0.02 |

| Costa Rica | 7 | 0.1 | India | 1 | 0.02 |

| Ireland | 7 | 0.1 | Indonesia | 1 | 0.02 |

| Denmark | 6 | 0.1 | Panama | 1 | 0.02 |

| Brazil | 5 | 0.1 | Portugal | 1 | 0.02 |

| Japan | 5 | 0.1 | Czech Republic | 1 | 0.02 |

| Peru | 5 | 0.1 | Romania | 1 | 0.02 |

| Puerto Rico | 5 | 0.1 | Russia | 1 | 0.02 |

| Austria | 4 | 0.1 | South Africa | 1 | 0.02 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the National Transparency Platform (PNT, 2018).

These first data reveal a first examination of the origin of the Guanajuatense vote abroad, contextualizing the importance of the participation of citizens of Guanajuato origin residing in the U.S. A second insight is that Guanajuatenses in European countries are the ones who stand out the most, even with respect to votes from countries on the southern border and from Latin American countries. Looking at Table 6, which groups countries by region, it is clear that practically nine out of ten votes came from Guanajuatenses concentrated in North America (USA and Canada); the second most important region is Europe with 7.93 percent, and Latin America with just 1.45 percent; finally, with less than 1 percent, come Asia and Africa. These data allow inferring questions about what the basic sociodemographic profile of the Guanajuatense voter is.

Table 6 Region of origin of the votes of Guanajuatenses abroad, 2018

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North America | 89.75 |

| Europe | 7.93 |

| Latin America | 1.45 |

| Asia | 0.85 |

| Africa | 0.02 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the National Transparency Platform (PNT, 2018).

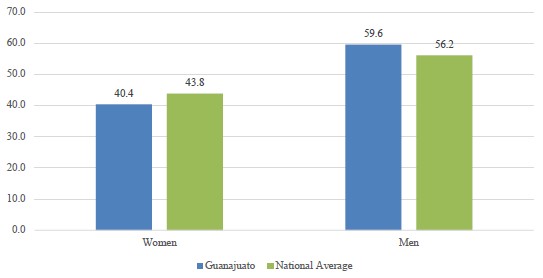

Like the global average observed in Table 3 regarding the gender of those who voted, in the case of Guanajuato voters this difference between men and women increases. Practically six out of ten votes correspond to men and four out of ten to women. Once again, the question must be asked about this phenomenon, which is opposed to voting trends in the national territory, wherein women vote more than men (see Graph 1).

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the PNT (2019).

Graph 1 Vote of Guanajuatenses abroad for presidential elections and national average of 2018, by sex

What is the age and sex of voters residing abroad?

Graph 2 shows another basic variable that outlines the profile of the Guanajuato voter abroad. When comparing the age of Guanajuatenses with the national average of foreign voters in the 2018 election, the first presents a similar behavior, but two nuances can be noticed: the first is that the average of Guanajuato voters in the age range of 18 to 44 years is below the national percentage; Guanajuato voters aged 45 and over residing abroad voted more, compared to national voters. Although it must also be said that the percentage differences are small.

It is also noteworthy that the bulk of foreign voters of Guanajuato origin are between the ranges of mature or adult age: practically seven out of ten voters are in the range of 30 to 54 years (68.7%). In other words, the majority of those who voted reached the age to exercise their electoral political right between 1982 and 2006, a context characterized by the deepest political changes in the Mexican political system, particularly through the phenomenon of alternation at the state level that culminated with the triumph of the opposition block in the presidency in the year 2000.

On the other hand, by not having registration and/or voting card at the level available in the country, it is difficult to interpret the phenomenon of participation, although there are similarities with the phenomenon of low participation of young people (from 18 to 29 years old), yet at the national level the youngest individuals of this group (those from 18 to 19 years old) vote to a larger extent that later decreases according to age; the data in Graph 2 shows that these young people of 18 and 19 years old are the least involved. And indeed, the life cycle validates the hypothesis that the older the individual, the more likely to vote, although at the level of voting abroad, participation drops noticeably at age 50, while at the national level the figure shows that this happens from the age of 70.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the INE (2018).

Graph 2 Guanajuatense and Mexican voters abroad in the 2018 election, by age groups

Who did the voters from abroad choose?

As mentioned before, the vote of Guanajuatenses abroad has an important history, but the experiences are still few. There have been barely three federal electoral processes allowing the modality of voting from abroad, and it is precisely the 2018 voting exercise that is of greatest interest due to the novelty of the vote to elect local authorities. In the case of the state of Guanajuato, an election was held in which Guanajuatenses abroad were able to vote not only for federal authorities, but also for local ones, particularly for governor.

In the political-electoral context of Guanajuato, the National Action Party has predominated in the governorship for more than two decades: since the extraordinary election of 1995 where the winner was Vicente Fox Quesada. Since that date, the PAN has won all the elections for governor, and likewise, has managed to keep control in the local Congress. Likewise, the PAN has also retained the mayor's offices of the municipalities with the greatest demographic and economic weight practically constantly.3

Yet the pertinent question according to our study is, does the PAN predominance extend beyond the borders of Guanajuato? The answer is found in Graph 3. In the 2006 election, 75.1 percent of Guanajuatenses abroad voted for Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, notably more than the average of voters abroad that reached 58.29 percent. The second most voted option that year was Andrés Manuel López Obrador (Alianza Por El Bien de Todos [Coalition for the Good of All]), with a percentage of 18.1 percent. The candidate by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI, acronym in Spanish for Partido Revolucionario Institucional) came in third place, Roberto Madrazo Pintado (Alianza por México [Alliance for Mexico]) (3.4%). Patricia Mercado, from the Social Democratic and Peasant Alternative Party (PASC, acronym in Spanish for Partido Alternativa Socialdemócrata y Campesina), obtained 3.3 percent of the votes. It is surprising that a recently created party like the PASC had practically the same percentage of votes as the candidate by a party as long-lived as the PRI.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the IFE (2006) and the INE (2018).

Graph 3 Vote of Guanajuatenses abroad in the presidential elections of 2006, 2012 and 2018

For the 2012 election, the PAN was once again the party most favored by the vote of Guanajuatenses abroad, but with a drop from 75.1 to 54.8 percent (more than twenty percentage points); the PAN candidate, Josefina Vázquez Mota, who came in third place in the final result of the election, obtained majority support from the vote abroad, and even locally (although this contrasts with the rest of the country, since Guanajuato was one of the three entities in which the PAN obtained more votes than their opponents).

The candidate of the left, AMLO (Progressive Movement Alliance [Alianza Movimiento Progresista]), came again in second place in the preferences of Guanajuatenses abroad, obtaining almost a quarter of these votes (23.2%). It is also noteworthy that only 18.3 percent of Guanajuatenses abroad gave their vote to who would become president of the republic, Enrique Peña Nieto (Commitment to Mexico Alliance [Alianza Compromiso por México]). The pattern of global results is similar for Guanajuatenses abroad and those within state territory: first, Josefina Vázquez Mota, 42.17 percent; then Andrés Manuel López Obrador, 39 percent; and finally Enrique Peña Nieto, 15.62 percent. Until this election, the partisan preferences of Mexicans and Guanajuatenses abroad tended notoriously towards the PAN.

There were noticeable changes in the 2018 election; the first phenomenon to highlight is that of high participation: 4,836 votes from Guanajuatenses abroad. As already mentioned, the number of votes probably doubled due to the possibility of being able to vote for the candidates for governor.

Along with this growth in voters, the voting behavior of Guanajuatenses abroad had a notable variation: the PAN lost the first place in the preferences of the Guanajuatense vote abroad (as well as the national average of this type of vote).4 The candidate by the Mexico First coalition, Ricardo Anaya, only obtained a quarter of the votes (25.7%), that is, he lost more than half of the support of Guanajuatenses abroad. On the other hand, the candidate by the coalition Together We Will Make History (Morena-PT-PES), reached a percentage similar to that reached by the PAN in previous elections: 65.2 percent of Guanajuatenses abroad voted for Andrés Manuel López Obrador, this representing a growth of more than forty percentage points. In the case of José Antonio Meade Kuribeña, candidate of the All Together For Mexico (Todos por México) (PRI- PVEM-PANAL) coalition, the voting was the lowest for a PRI candidate: 4.3 percent. The independent candidate Jaime Heliodoro Rodríguez Calderón obtained 3.2 percent of the preference of the Guanajuatense foreign vote.

A global analysis reveals the constant loss of votes by the PAN candidates against AMLO and the parties that have nominated him. It is true that AMLO remained in second place in the 2006 and 2012 elections, but not within a competitive distance of the PAN in Guanajuato. The 2018 election represented a substantial change in electoral behavior. One of the hypotheses to explain this change is the increase in voting, that is, that the new voters in this modality were able to reverse the PAN-leaning trend. Observing the number of votes, the PAN even increased its votes compared to the last elections, but the novelty of the postal vote may have encouraged a greater participation of new voter profiles. Another hypothesis is that AMLO's successful campaign, unlike to other years, convinced even Guanajuato citizens who had previously not been convinced to support him.

Graph 4 shows the change in the electoral behavior of the Guanajuato diaspora with respect to Guanajuatenses residing in its territory, both to elect president of the republic and governor of the state. The voting difference received by the presidential candidate by Together We Will Make History, AMLO, was 65.2 percent of the votes of Guanajuatenses living abroad, against 30.4 percent of those living in state territory. In the case of the governorship of the state, the candidate Diego Sinhue Rodríguez Vallejo, candidate by the PAN, PRD and PMC through the Guanajuato First (GF, after the Spanish name Por Guanajuato al Frente) coalition comfortably won the election with the local vote (49.9%), while the candidate that came second place, Ricardo Sheffield of the JHH coalition (Morena, PT and PES parties) obtained 24.1 percent. The contrast appeared with the Guanajuatense vote from abroad: Sheffield reached 56.8 percent, while Diego Sinhue Rodríguez only obtained 32.7 percent of this voting pool.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the INE (2018).

Graph 4 Comparative vote of Guanajuatenses abroad and in state territory for governor and president of the republic in 2018

Therefore, the trend in which in the state of Guanajuato the PAN candidate came first place in extraterritorial suffrage is broken. In the 2018 election, the JHH candidates received the most votes from Guanajuatenses abroad. Even in the vote for president of the republic, the national average for this type of vote was slightly exceeded (64.9%).

In this sense, it could also be noted that Diego Sinhue received more votes from Guanajuatenses abroad than Ricardo Anaya; in turn, AMLO was voted more than Ricardo Sheffield.

Some challenges of the Guanajuatense vote from abroad

What problems did voting from abroad present for emigrants from Guanajuato? How to increase the number of voters from abroad? What will the electoral behavior of Guanajuatenses abroad be in future elections?

In order to answer the first question, it should be noted that the process for registering and requesting the sending of electoral ballots supposes a high interest from the citizen for participating in voting. Without a high motivation on the part of Mexicans residing abroad to influence the elections, the process may not be completed, or even started. Research is needed to investigate the interest (and/or lack of it) of Mexicans abroad to vote remotely, as well as to learn more about the social determinants of casting a transnational vote.

The Blair Center of Southern Politics and Society survey, from the University of Arkansas (Medina Vidal, 2018, slides 15, 17 and 23), provides us with data on the profile of the Mexican voter in the US. The study indicates that just over half paid a lot or some attention to Mexican politics (54.8%). When asked how easy was it to learn about the vote of Mexicans residing in the U.S., for a majority of 67.2 percent it was easy or more or less easy to learn about the vote; for

32.7 percent it seemed that it was somewhat difficult or very difficult. A second question, which inquired about the process, was how easy or difficult was it to vote from abroad; for six out of ten respondents it was easy or more or less easy (59%); yet for four out of ten (41%), it was very difficult or somewhat difficult. Through both questions it becomes clear that significant percentages of Mexicans in the U.S. had some difficulty in understanding the instructions of and/or actually sending the voting envelopes. These data help to understand in part the small number of Mexicans abroad who made the request, and that practically only half of did complete the process.

It must be remembered that in Mexico the logic of the electoral bodies is to banish the distrust that citizens usually have on political processes. The best mechanism that has been made use of to make an electoral process reliable is to be careful with each of the requirements that allow citizens to exercise their right to vote. The care that is put in these processes sometimes reaches extremes, having the effect of bureaucratization. This implies a relevant effect for the democratic-electoral process: citizens want to exercise their right in an easy way, and at the same time they want the full guarantee that their vote will be counted and respected. In this sense, in Mexico the exercise of the vote from abroad has led to the bureaucratization of the process to ensure that there are no suspicions of vote mismanagement, but at the same time it is discouraging due to the time and effort involved in following up on the entire process. Given this state of things, the challenge is clear: finding a simple and reliable mechanism so that more Mexicans can exercise their right to vote.

On the other hand, there is also the commitment of both federal and local electoral bodies to promote citizen participation. In the 2018 election there was a notorious role of both institutions in promoting the vote of Mexicans and Guanajuatenses abroad. In the case of the Electoral Institute of the State of Guanajuato (Instituto Electoral del Estado de Guanajuato), different strategies were carried out to promote ID issuance, registration with the LNERE, and the exercise of the vote by Guanajuatenses from abroad, which included campaign tours abroad, the Vote From Abroad television series, television, radio and press ads, etc. (Instituto Electoral del Estado de Guanajuato, 2018).

All in all, one of the boldest responses that the federal electoral authority has given to increase voting by Mexicans abroad is electronic voting, thus making the processes easier, and guaranteeing the right to vote, as well as its secrecy. In 2018 the INE issued guidelines that establish the general characteristics of the online electronic voting system for Mexicans residing abroad (Instituto Nacional Electoral, 2019). These guidelines describe the process that Mexicans abroad must follow in order to vote in the upcoming elections. They went into effect in the 2020 local elections in several states, representing a first exercise to observe the effectiveness and implementation of electronic voting in a federal election.

Another challenge of voting abroad is to consider whether the electoral legislation should allow political parties, their candidates, and independent candidates, to campaign abroad before and during the electoral campaign. Currently, there are several provisions in the LGIPE that consider it an infraction to carry out campaign and pre-campaign acts, or that prohibit the hiring of advertising on radio and television abroad. In effect, the LGIPE establishes in its Article 443, subparagraph g), that it is an infraction for political parties to carry out pre-campaign or campaign acts in foreign territory.

While Article 447, subparagraph b) of the same law, sets forth as an infraction for citizens, leaders and members of political parties to hire propaganda on radio and television, both in national territory and abroad, directed at personal promotion for political or electoral purposes. The two articles above are a sign that it is necessary to further regulate the linking and promotion of candidates and political parties in relation to voting abroad, given that at least the two cited regulations make no reference to the carrying out of political campaigns through digital platforms with international scope yet hired in national territory.

In this sense, it seems appropriate to continue delving into the lessons learned from the experiences of voting from abroad. The development of more effective regulations to promote transnational citizenship implies the implementation of new strategies to link the diaspora of Mexicans abroad. This implies overcoming the formal mechanisms of the electoral organizations in force in Mexico, and involving migrant associations, political parties, and subnational authorities in the expansion of the political participation of Mexicans beyond national borders.

Closing remarks

In this analysis we have established a broad framework of understanding on the vote of Mexicans and Guanajuato natives abroad, from the transnational perspective. This represents an evolution in the institutional recognition of the political rights of migrants, providing the legal-formal basis for transnational citizenship. This citizenship is also exercised locally; in this case, it was observed through the election of governor, despite how late and slow this legal recognition of extraterritorial voting has been in Guanajuato.

Despite the progressive growth of Mexican emigrants' interest in participating in electoral processes in Mexico, their participation remains marginal. Indeed, according to data from the 2018 election, at the national level of the nearly 13 million Mexicans residing abroad, only about 100 000 votes (98 854) were received, that is, less than 1 percent (0.76%) of the Mexican population estimated to reside abroad voted in the last elections. In the case of Guanajuato, the percentage is lower, because of the more than one million Guanajuato emigrants, only near 5 000 (4 836) votes were received, that is, not even 0.5 percent (0.48%) of Guanajuatenses residing abroad. The percentage decreases if we consider people born abroad to a Mexican father or mother, that is, second-generation migrants; this last population is estimated at more than 22 million people.

In the 2018 electoral process, there was a substantial change in the electoral behavior of Mexicans residing abroad. The National Action Party (PAN) lost first place in the preferences of the extraterritorial vote both nationally and in the state of Guanajuato, which was its only stronghold in the internal vote for president of the republic. This article expresses at least three hypotheses that would explain this change. The first would have to do with the increase in the extraterritorial suffrage vote, which doubled from 2012 to 2018. The second has to do with the fact that the electoral campaign of the winning candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador had international scope. The third relates to the fact that the migrant vote leans towards the opposition block, in this sense, the new opposition option was that of the winning candidate, while the PAN ceased to be seen as an opposing political force.

Finally, the disaffection to participate in the electoral processes from abroad on the part of Mexicans and Guanajuato natives is significant, as well as the minority vote of young people and women. Therefore, it is necessary to continue inquiring into the different dimensions of the political rights of Mexican migrants abroad, in order to delve deeper into the local particularities of each diaspora.

Translation: Fernando Llanas

REFERENCES

Aboites, G., Verduzco, G. F. y Martínez, F. (2007). Estrategias de vidas: migración y remesas como paliativo a la pobreza en Guanajuato. Trayectorias: Revista de Ciencias Sociales de La Universidad Nacional de Nuevo León, (25), 18-32. [ Links ]

Aguilar López, J. (2019). Análisis del voto joven en la elección de 2018 en México. En O. Díaz Jiménez, V. Góngora Cervantes y M. Vilches Hinojosa (Coords.), Las elecciones críticas de 2018. Un balance de los procesos electorales federales y locales en México, (pp. 229-247). Ciudad de México: Universidad de Guanajuato/Grañén Porrúa. [ Links ]

Alarcón Olguín, V. (2016). El sufragio transnacional y extraterritorial en América Latina. Tendencias recientes y nuevos escenarios. En G. E. Emerich y V. M. Alarcón Olguín (Eds.), Sufragio transnacional y extraterritorial. Experiencias comparadas, (pp. 20-35). Ciudad de México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Instituto Interamericano de Derechos Humanos-Centro de Asesoría y Promoción Electoral, Costa Rica/ Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología [ Links ]

Alarcón, R. (2012). El debate sobre la migración cero. México: Letras Migratorias Newsletter. Consejo Nacional de Población/Observatorio de Migración Internacional. [ Links ]

Baubök, R. (1994). Transnational Citizenship: Memebership and Rigths in Internacional Migration. Aldershot: Edwar Elgar. [ Links ]

Beltrán Miranda, Y. (2017). El voto de los mexicanos residentes en el extranjero. En L. Ugalde y S. Henández (Coords.), Fortalezas y debilidades del sistema electoral mexicano. Perspectiva federal y local, (pp. 462-487), México: Integralia Consultores. [ Links ]

Canales, A. (2006). Remesas y desarrollo en México. Una visión crítica desde la macroeconomía. Papeles de Población, 12(50), 10-196. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2002). La era de la información: Economía, sociedad y cultura. Volumen I: La sociedad red. México: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión Pública (CESOP). (2004). El voto de los mexicanos en el extranjero. México: Cámara de Diputados. Recuperado de https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwifh6vE0YL3AhXjKUQIHddfCnYQFnoECAsQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww3.diputados.gob.mx%2Fcamara%2Fcontent%2Fdownload%2F21151%2F104976%2Ffile%2FFATSM005%2520El%2520voto%2520de%2520los%2520mexicanos%2520en%2520el%2520extranjero.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0Oodzvk5TS5NxnOgXSU8FX [ Links ]

Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (CPEUM). (5 de febrero de 1917). Diario Oficial de la Federación, Ciudad de México. [ Links ]

Constitución Política para el Estado de Guanajuato (CPEG). (3 de septiembre de 1917). Periódico Oficial del Estado, núm. 32, Guanajuato. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población, Fundación BBVA Bancomer y BBVA Research. (2017). Anuario de migración y remesas. México 2017. México: Autores. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población, Fundación BBVA Bancomer y BBVA Research. (2018). Anuario de migración y remesas. México 2018. México: Autores . [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población, Fundación BBVA Bancomer y BBVA Research. (2016). Anuario de migración y remesas. México 2016. México: Autores . [ Links ]

Cordourier Real, C. R. y Aguilar López, J. (Coords.). (2018). Participación ciudadana y sociedad civil en el proceso de democratización en México. Guanajuato: Universidad de Guanajuato. [ Links ]

Delgado Wise, R. y Márquez Covarrubias, H. (2006). El sistema migratorio México-Estados Unidos: dilemas de la integración regional, el desarrollo y la migración. Migración y Desarrollo, 4(7), 38-62. https://doi.org/10.35533/myd.numero07 [ Links ]

Durand, J. (2016). Historia mínima de la migración México-Estados Unidos. Ciudad de México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Durand, J. y Arias, P. (2005). La vida en el norte. Historia e iconografía de la migración México- Estados Unidos. Guadalajara, México: El Colegio de San Luis/Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

Durand, J. y Schiavon, J. A. (Eds.). (2014). Perspectivas migratorias III. Los derechos políticos de los mexicanos en el exterior. México: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas. [ Links ]

Emmerich, G. E. y Alarcón Olguín, V. (Eds.). (2016). Sufragio transnacional y extraterritorial. Experiencias comparadas. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Instituto Interamericano de Derechos Humanos-Centro de Asesoría y Promoción Electoral-Costa Rica/ Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. [ Links ]

Espinoza Valle, V. A. (Coord.). (2016). El voto a distancia. Derechos políticos, ciudadanía y nacionalidad. Experiencias locales. México: Ediciones y Gráficos Eón/Instituto Electoral del Estado de Guanajuato. [ Links ]

Faist, T. (2015). Migración y teorías de la ciudadanía. En P. Mateos (Ed.), Ciudadanía múltiple y migración. Perspectivas latinoamericanas, (pp. 25-56). México: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas /Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [ Links ]

Fix-Fierro, H. (2006). Los derechos políticos de los mexicanos. México. México. Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

García Zamora, R. (2007). Migración internacional y desarrollo en México: tres experiencias estatales. En R. Fernández de Castro (Ed.), Las políticas migratorias en los estados de México. Una evaluación, (pp. 45-71). México: Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

García Zamora, R. (2012). Cero migración: Declive de la migración internacional y el reto del empleo nacional. Migraciones Internacionales, 6(23), 273-283. https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v6i23.733 [ Links ]

Instituto Electoral del Estado de Guanajuato (IEEG). (2018). Programa Anual de trabajo. Comisión Especial para el Voto de los Guanajuatenses Residentes en el Extranjero. Guanajuato: Sin Autor. Recuperado de http://www.ieeg.org.mx/pdf/Consejo%20General/Comisiones/VGRE%20PAT%202018.pdf [ Links ]

Instituto Federal Electoral (IFE). (diciembre de 2006). Informe final sobre el voto de los mexicanos residentes en el extranjero 2006. Recuperado de https://portalanterior.ine.mx/documentos/votoextranjero/libro_blanco/index.htm [ Links ]

Instituto Federal Electoral (IFE). (2012). Informe final sobre el voto de los mexicanos residentes en el extranjero. Proceso electoral 2011-2012. México. Recuperado de http://www.votoextranjero.mx/documents/52001/54193/Informe+Final+del+VMRE+VERSI ON+FINAL+nov12.pdf/20e722b2-188b-417d-81e7-f0a54753e7cb [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional Electoral (INE). (2018). Voto de los mexicanos residentes en el extranjero. [página web]. INE. Histórico. Recuperado de https://votoextranjero.mx/web/vmre/historico [ Links ]

INE (Instituto Nacional Electoral). (2019). Lineamientos que establecen las características generales que debe cumplir el sistema del voto electrónico por internet para las y los mexicanos residentes en el extranjero. Acuerdo del Consejo General INE/CG243/2019. Recuperado de https://repositoriodocumental.ine.mx/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/109376/CGex20190 5-08-ap-4.pdf [ Links ]

Joppke, C. (2010). Citizenship and immigration. Cambridge, Reino Unido: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Lamy, B. y Rodríguez Ortiz, D. I. (2011). Migración y familia en León, Guanajuato. Acta Universitaria, 21(3), 23-52. [ Links ]

Marshall, T. H. (1997). Ciudadanía y clase social. Revista de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Reis), (79), 297-344. [ Links ]

Medina Vidal, X. (2018). Evaluación del voto de las y los mexicanos residentes en Estados Unidos: elecciones 2018. [diapositivas de Power Point]. Instituto Nacional Electoral. Voto de los y las mexicanas residentes en el extranjero. Recuperado de https://www.votoextranjero.mx/documents/52001/485790/10.+Evaluaci%C3%B3n+VMRE+e n+EE.UU..pdf/17d60c0c-9314-4fc7-892d-9a5bd9595fa8 [ Links ]

Mateos, P. (Ed.). (2015). Ciudadanía múltiple y migración. Perspectivas latinoamericanas. México: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas /Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [ Links ]

Moctezuma, M. (2004). Viabilidad del voto extraterritorial de los mexicanos. Migración y Desarrollo, 2(3), 107-119. [ Links ]

Navarro, C. (2017). Panorama comparado del voto extranjero en América Latina. Revista Elecciones, 16(17), 169-194. [ Links ]

Navarro Fierro, C., Robles Ríos, A., Almaraz Anaya, J., Sánchez Rodríguez, M. y Escutia, J. L. (2016). Estudios Electorales en Perspectiva Internacional Comparada. El voto en el extranjero en 18 países de América Latina. México: Instituto Nacional Electoral. [ Links ]

Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia (PNT). (23 de noviembre de 2018). Respuesta a la solicitud de acceso a la información con folio 2210000354518. Instituto Nacional Electoral. México. [ Links ]

Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia (PNT). (22 de agosto de 2019). Respuesta a la solicitud de acceso a la información con folio 2210000182219. Instituto Nacional Electoral. México. [ Links ]

Pries, L. (2017). La transnacionalización del mundo social: espacios sociales más allá de las sociedades nacionales. México: El Colegio de México-Centro de Estudios Internacionales. [ Links ]

Rojas Choza, F. A. y Vilches Hinojosa, M. (2017). Migración, ciudadanía múltiple y el derecho a integrar autoridades electorales en México. Apuntes Electorales, 16(57), 109-144. [ Links ]

Sistema Estatal de Información Estadística y Geográfica. (2017). 18 de diciembre día internacional del migrante. [Boletín]. Gobierno de Guanajuato. Instituto de Planeación Estadística y Geografía. Recuperado de https://seieg.iplaneg.net/seieg/doc/Dia_Internacional_del_Migrante_2017_iatr181216_151336 5967.pdf [ Links ]

Vega-Macías, D. (2015). Migración y dinamismo demográfico: un análisis exploratorio de los municipios del estado de Guanajuato, México (1990-2010). Acta Universitaria, 24(6), 29-36. https://doi.org/10.15174/au.2014.652 [ Links ]

Vega Briones, G. y González Galbán, H. (2009). Clubs de migrantes y usos de remesas: El caso de Guanajuato, México. Portularia, 9(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

Vilches Hinojosa, M. (26-28 de julio de 2017). La ciudadanía transnacional. El caso de las personas migrantes [simposio]. En 9° Congreso Latinoamericano de Ciencia Política ALACIP ¿Democracia en Recesión? Montevideo, Uruguay: Asociación Latinoamericana de Ciencia Política/Asociación Uruguaya de Ciencia Política. [ Links ]

Vilches Hinojosa, M. (2019). El sufragio extraterritorial en México para elegir presidente de la república en 2018. En O. F. Díaz Jiménez, V. Góngora Cervantes y M. Vilches Hinojosa (Coords.), Las elecciones críticas de 2018. Un balance en los procesos electorales federal y locales en México, (pp. 159-184). México: Grañén Porrúa/Universidad de Guanajuato. [ Links ]

Zong, J., Batalova, J. y Hallock, J. (2018). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. EE. UU.: Migration Policy Institute. [ Links ]

1 The 2010 Population and Housing Census (Censo de Población y Vivienda) indicated that 123 186 Guanajuatenses emigrated from Mexico during the period from 2005 to 2010, out of which 97.1 percent went to the United States. The Institute of Planning, Statistics and Geography of the State of Guanajuato (Instituto de Planeación, Estadística y Geografía del Estado de Guanajuato) estimated that more than one million people born in Guanajuato lived in the U.S. in 2017 (Sistema Estatal de Información Estadística y Geografía, 2017).

2 Two databases were obtained through requests for access to information through the National Transparency Platform (PNT or Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia) made in the first half of 2019; in one of them, the Secretariat for Migrants and International Liaison of the Government of the State of Guanajuato (Secretaría del Migrante y Enlace Internacional del Gobierno del Estado de Guanajuato) reported 117 associations of Guanajuato migrants, while the second database was provided by the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior), reporting 364 associations of migrants and Guanajuato natives.

3 There are some exceptions: the capital of Guanajuato has been governed only twice by the PAN since that alternation at the gubernatorial level. And the municipality of León de los Aldama, the most densely populated municipality and the economic engine of the state, has been the PAN bastion since 1988, with a single defeat in 2012 against a PRI-PVEM (Partido Verde Ecologista de México [Ecologist Green Party of Mexico]) alliance. In 2015 the PAN regained the municipal presidency.

4 Candidate Ricardo Anaya of the PAN-PRD-PMC alliance obtained 32.7 percent, while Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Morena-PT-PES, obtained a higher percentage than the vote made in national territory: 64.86 percent, a percentage similar to that reached in previous elections by the PAN in the entity, 56.8 percent (practically six out of ten votes went to Andrés Manuel López Obrador). José Antonio Meade barely reached 4.9 percent of the Guanajuatense vote from abroad

Received: April 26, 2020; Accepted: March 23, 2021

texto en

texto en