Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.13 Tijuana ene./dic. 2022 Epub 06-Jun-2022

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2431

Papers

Return Migration in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Scoping Review

1 University of Alberta, Canada higinio@ualberta.ca

2 Universidad de Guanajuato, Mexico, is.vasquezventura@ugto.mx

3 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Mexico, ivan.2299@hotmail.com

4 University of Alberta, Canada, zahoui@alberta.ca

The following article determines the scope and nature of the empirical evidence on migrants returning to Latin American and Caribbean countries. Following the scoping review methodology, 23 empirical studies published in indexed journals were included. The data were synthesized using descriptive statistics and conventional content analysis. Most of the participants are migrants from Mexico (n=19) and the return country is the United States (n=20). Four emerging categories were identified: a) health and well-being, b) social, political, and cultural context, c) addictions, and d) reasons for return. The phenomenon under study shows innovation due to the limited scientific literature that analyzes return migration. It is concluded that people returning to their places of origin face unfavorable economic, political, and health situations.

Keywords: 1. migration; 2. return; 3. migrants; 4. Latin America; 5. Caribbean

El artículo determina el alcance y la naturaleza de la evidencia empírica es decir artículos académicos referentes a los migrantes que regresan a países en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Mediante la metodología de las Revisiones Sistemáticas Exploratorias, se incluyeron 23 estudios empíricos publicados en revistas indexadas los datos se sintetizaron mediante estadística descriptiva y análisis de contenido convencional. En su mayoría, los participantes son migrantes originarios de México (n=19), y el país desde el cual retornan es Estados Unidos (n=20). Se identificaron cuatro categorías emergentes: a) salud y bienestar, b) contexto social, político y cultural, c) adicciones y d) motivos de retorno. El fenómeno en estudio muestra innovación debido a la limitada literatura científica que analiza la migración de retorno. Se concluye que las personas que regresan a sus lugares de origen se enfrentan a situaciones desfavorables económicas, políticas y de salud.

Palabras clave: 1. migración; 2. retorno; 3. migrantes; 4. Latinoamérica; 5. Caribe

Introduction

The current pandemic triggered by Covid-19 has brought about important changes in migration processes. Return migration takes place when international migrants return to their country of origin voluntarily or by forced repatriation (Lozano & Martínez, 2015; International Organization for Migration (OIM), 2019; Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development (OCDE), 2017). There has been an increase in the rate of return migration of 42% as of the first decade of the 21st century in Latin America and the Caribbean; main reasons for return include deportation policies in host countries such as the United States (OIM, 2019). However, it is argued that this percentage may be higher due to the different measurements used in each country, and due to the difficulties in calculating unauthorized migration (Azose & Raftery, 2019).

Migration is a social process, characterized by the displacement of individuals from their place of origin to another (Micolta, 2005). People continue to migrate primarily due to economic and labor inequality; however, others migrate due to violence, war, and climate change in their places of origin (Crosa, 2015; Micolta, 2005). In 2019, more than 270 million migrants were reported globally, accounting for 3.9% of the total world population; more than 70 million migrants came from Latin America and the Caribbean (United Nations, 2020), positioning the

U.S. as the country with the highest index of Latin American migrants who want to enter this country. Migration patterns and tendencies have been studied for years; it is known that displacements inside the region are no longer a common process for Latin Americans, but international mobility processes, which fix their destination in the North American region (Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía (Celade), 2006).

According to Aruj (2008), the main reasons for migration in Latin America and the Caribbean concur in a biopsychosocial sphere. The search for better lifestyles, economic and political imbalances, the increase of violent processes, and the lack of labor options in their country of origin are the most reported reasons. Such aspects are related to the context where individuals develop, spurring a search to meet basic needs. Poverty and inequality in Latin American and Caribbean countries is also linked to migration (Fernández, Gómez, & Pérez, 2020; Lozano & Martínez, 2015; Navarro, Ayvar, & Zamora, 2016).

The empirical evidence on international migration largely focuses on the migration and acculturation processes of people in recipient countries (Martine, Hakkert, & Guzmán, 2001), on their health and wellbeing (Cabieses, Gálvez, & Ajraz, 2018), and on the fragmentation of the families and societies that stay behind (Bonilla, 2020; Fernández, 2020; Fernández et al., 2020). However, it is necessary to ascertain the personal, social, and political circumstances faced by migrants who return to their home country, considering this problem as a phenomenon that has effects on the home and host countries (Cataño & Morales, 2015). Indubitably, it is a phenomenon that needs attention, for only in 2019, the U.S. (the main migrant host country) deported 267, 000 people of various ages to their places of origin, out of which most were from the Central America North Triangle (Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador), and additionally, Mexico.

With the aim to learn about the social, cultural, political, and health conditions of returning migrants, the purpose of this systematic scoping review is to compile the available empirical evidence of migrants who return to their countries of origin in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Methodology

The present document follows the guidelines of Scoping Reviews (SR) which tries to summarize the existing empirical evidence regarding a topic with a view to generating new hypotheses, research agendas, or proposing future studies. One of the goals of SR is to show a broader and detailed panorama of the phenomenon under study, in comparison with a systematic traditional review, which tries to address a particular statement (Munn et al., 2018).

The methodology consists of five stages: 1) production of the research question and search strategy; 2) systematic literature search; 3) revision and selection of studies from several inclusion and exclusion criteria; 4) data extraction; and 5) result analysis and report (Fernández, King, & Enríquez, 2020).

Stage 1: Research Question

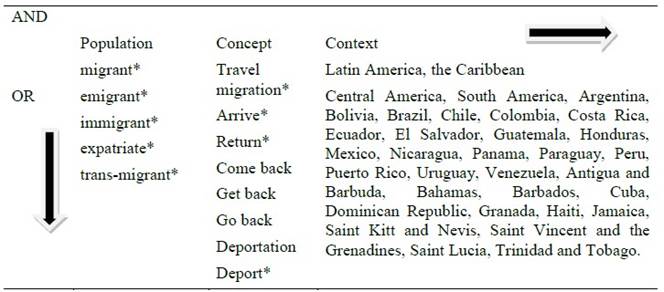

To frame the research question, it was necessary to use the components suggested by Peters et al. (2017), which comprise the following fields: population, concept, and context (see chart 1). Due to the foregoing, the question that guided this SR was: What is the scope and nature of the empirical literature on Latin American and Caribbean migrants who return to their home countries? According to this question, migrants are the population, the concept is return migration, and the context is Latin America and the Caribbean.

Stage 2: Search Strategy and Search Terms

Over a four-month period (April-July 2020), the research team performed a systematic search to gather empirical evidence related to the research question. The query was carried out by two doctoral students in Mexico and Canada. For broadening the search, databases specialized in health sciences, social sciences, and humanities were consulted: PubMed, Scopus, Literatura Latinoamericana y el Caribe en Ciencias de la Salud (LILACS), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINALH), Psyinfo, Scielo, Dialnet, and Cuiden.

To encompass the components of the research question keywords, Boolean operators corresponding to the population and concept were combined with context as shown in table 1.

Inclusion criteria for this exploratory systemic review were: 1) migrants who returned to their country of origin; 2) migrants returned to Latin America or the Caribbean; 3) full-text articles published in English and Spanish. Whereas articles on migrants who would not return to Latin America or the Caribbean, people who emigrated within their own country, migrants still living abroad, and migrants only visiting their home country were excluded.

Stage 3: Information Management and Article Selection

The articles identified in the databases were exported to RefWorks and Mendeley, which are bibliographic reference management software programs. Later, Covidence software was utilized to facilitate the selection of articles by independent reviewers. Disagreements on the inclusion of articles were solved by the consensus of the reviewers. Resorting to the flowchart (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)) (Moher et al., 2009) was useful to depict the process of detection and selection of the articles included in the present review (see figure 1).

Stage 4: Data Extraction and Summary

To summarize the information, a database was created in Excel by the authors to address the needs of this study. This enabled the correct extraction of the most important findings in each article to later be checked and summarized. In this stage of the process, the reviewer registered the characteristics of each article: author, publication year, goal of the study, research approach, research design, country, characteristics of the participants, and main results; independently, a second reviewer verified this information. This technique served as a validation to perfect the results proposed in the goal of the review. The information from this extraction was summarized in Word documents to undergo qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Stage 5: Analysis and Report of Results

To identify and summarize the most relevant topics, a conventional content analysis was decided, as proposed by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). The steps of this sort of analysis are: 1) a repeated reading of the data to have an overview of the phenomenon; 2) word by word reading to derivate the codes; 3) drafting of the first impressions of the texts; thus, the codes appear to be classified into categories; 4) defining each category and code created; and 5) identification of categories to use based on their concurrence and relationship. As well, a numeric analysis was run by means of frequencies and percentages to analyze quantitative data. Excel and QUIRKOS software programs aided in quantitative and qualitative analyses, respectively.

Results

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 23 articles analyzed in this systematic review on return migration in Latin American and Caribbean countries. By and large, they are empirical studies published between 2008 and 2019. Sixteen are quantitative, five qualitative, while two, mixed. The authors point at the use of a theoretical framework to guide the research eight times. The sampling methods were random (n = 3); convenience (n = 4); survey-based (n = 4); stratified systematic (n = 1); probabilistic (n = 1); and, selective by means of street dissemination (n = 1). In the studies that clearly defined data collection techniques, the authors mainly resorted to interviews, surveys, and questionnaires. Most of the participants are return migrants from Mexico 82% (n = 19), while 18% (n=4) corresponds to individuals from Dominican Republic, El Salvador, and Colombia. Finally, Table 3 breaks down the key results of the analyzed articles.

Table 2 Characteristics of Studies on Return Migration in Latin American and Caribbean Countries

| # | Author and year | Sort of study | Design | Theory | Methods | Sampling | Sample | Country of origin | Ejecting country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Canedo et al., 2019) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Survey | Random sampling | n=345 348 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 2 | (Waldman et al., 2019) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Questionnaire | Random sampling | n=7 716 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 3 | (Ruth et al., 2019) | Empirical | Qualitative | n/a | Semi-structured in-depth interview | Convenience | n=13 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 4 | (Vega et al., 2019) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Interview | n/a | n=952 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 5 | (Padilla et al., 2018) | Empirical | Mixed | n/a | Interview | n/a | n=23 | Dominican Republic | U.S./Puerto Rico |

| 6 | (Zapata et al., 2018) | Empirical | Qualitative | n/a | Semi-structured interview | n/a | n=23 | Colombia | Spain |

| 7 | (Fernández et al., 2018) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Survey | n/a | n=229 | Colombia | U.S./Venezuela |

| 8 | (Martínez et al., 2018) | Empirical | Quantitative | Acculturation stress | Questionnaire | Convenience | n=1 383 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 9 | (Pinedo et al., 2018) | Empirical | Quantitative | Health care ecologic model | Questionnaire | Selective sampling by street dissemination | n=132 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 10 | (Horyniak et al., 2017) | Empirical | Quantitative | Ager and Strang’s framework concept for integration | Survey | Convenience | n=339 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 11 | (Arenas et al., 2015) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Survey | n/a | n=518 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 12 | (Bojorquez et al., 2015) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Survey | n/a | n=1 619 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 13 | (Duncan, 2015) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Interview | n/a | n=18 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 14 | (Muñoz et al., 2015) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Survey | Convenience | n=283 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 15 | (Negy et al., 2014) | Empirical | Quantitative | Acculturation stress and cognitive theory of maladjustment | Questionnaire | n/a | n=66 | El Salvador | U.S. |

| 16 | (Rangel et al., 2012) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Questionnaire, VIH Test | Probability based | n=693 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 17 | (Robertson et al., 2012a) | Empirical | Mixed | Risk environment frame | Survey, Interview | Survey based | n=309 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 18 | (Robertson et al., 2012b) | Empirical | Qualitative | Risk environment frame | Interview | Survey based | n=12 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 19 | (Robertson et al., 2012c) | Empirical | Quantitative | Acculturation model for the use of substances by Latin American adolescents | Questionnaire | Survey based | n=328 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 20 | (Ullmann et al., 2011) | Empirical | Quantitative | Hispanic paradox | Interview | Random sampling | n=2 121 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 21 | (Ojeda et al., 2011) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Interview | Survey based | n=24 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 22 | (Borges et al., 2009) | Empirical | Quantitative | n/a | Interview | Stratified sample, systematic sampling | n=1 630 | Mexico | U.S. |

| 23 | Sowell et al., 2008) | Empirical | Qualitative | n/a | Interview | n/a | n=10 | Mexico | U.S. |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on this exploratory systematic review.

Table 3 Main Results of Studies on Return Migration in Latin American and Caribbean Countries

| # | Author and year | Key results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Canedo et al., 2019 | 1) Economy; 2) missing relatives; 3) family issues in Mexico; 4) migration problems; 5) problems in the U.S. |

| 2 | Waldman et al., 2019 | 1) Association between migrating to the U.S. and psychiatric problems. |

| 3 | Ruth et al., 2019 | 1) DACA addressees experience guilt when they return to Mexico and leave their parents behind. However, they are more empathic toward their parents’ sacrifices. |

| 4 | Vega et al., 2019 | 1) Physical restrictions; 2) emotional or mental angst; 3) migrants forcibly returned to Mexico are 41% less likely to have health care coverage. |

| 5 | Padilla et al., 2018 | 1) Having a deportation background or being gay/bisexual were positively related to acculturation stress; 2) acculturation stress levels were related to the probability of having a higher risk of acquiring HIV. |

| 6 | Zapata et al., 2018 | 1) The impact of the economic crisis on the conditions of labor and employment; 2) economic crisis and return; 3) the various faces of the returnees; 4) the role of supportive social networks; 5) employment and labor conditions; 6) health care and wellbeing; 7) plans and expectations. |

| 7 | Fernández et al., 2018 | 1) Deported men previously imprisoned in the U.S. and /or Puerto Rico; 2) deported male labor, linked to the deportation regime directly to the Caribbean tourist industry, where often they find additional risks; factors embedded in the social and structural fabric of tourist areas. |

| 8 | Martínez et al., 2018 | 1) Migration routes; 2) migration time; 3) poor housing conditions and access to public services; 4) very good or excellent health status; 5) chronic disease prevalence was low, save hypertension. |

| 9 | Pinedo et al., 2018 | 1) Forty-five percent reported current depression symptoms; 2) being related with crime before deportation; 3) drug use. |

| 10 | Horyniak et al., 2017 | 1) The command of “halves and markers” was associated with recent drug use: having looked for a job in Tijuana, and family affluence; 2) in the realm of the “facilitators,” incarceration background in the U.S. and Mexico was positively associated with recent drug use; 3) in “Foundations,” having health care insurance was negatively associated to the use of drugs. |

| 11 | Arenas et al., 2015 | 1) Associated factors: males prevail in deportations, secondary schooling, use of inhalable drugs such as cocaine and HIV-related stigma; 2) low adherence to antiretroviral treatment because of the HIV stigma. |

| 12 | Bojorquez et al., 2015 | 1) Twelve percent of men and 39.8% of women deported experienced symptoms of mental disorders; 2) the most frequent symptoms were: being nervous or tense, being sad, and sleeping problems |

| 13 | Duncan, 2015 | 1) There is a link between deficient health and higher probability of returning to Mexico; 2) the economic characteristics are associated to the return to Mexico; 3) English speakers are less prone to return to Mexico; 4) having a spouse or children in Mexico is associated to a higher return probability. |

| 14 | Muñoz et al., 2015 | 1) Structural vulnerability conditions in Mexico and the U.S., which migrants understand as a central experience of the disease; 2) the unique challenges migration poses for health care male professionals and the families in migrant-ejecting communities; 3) transnational dimensions of angst and disorder. |

| 15 | Negy et al., 2014 | 1) Acculturation stress was correlated to lack of psychological housing. |

| 16 | Rangel et al., 2012 | 1) Sixteen percent of men tried new drugs after being deported, including heroin, methamphetamines and these two combined; 2) trying new drugs after deportation was independently associated with imprisonment in the U.S., being sad after deportation, and perceiving that the current lifestyle increases the risk of HIV/AIDS. |

| 17 | Robertson et al., 2012a | 1) Women reported drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana for the first time in adolescence; 2) almost all women occasionally did drugs during their adolescence in U.S. including intravenous drugs; 3) various women served long times in prison; 4) the most recent reasons for female deportations were being arrested, break their parole and having a record of unauthorized entrance into the U.S.; 5) looking for drugs was an important concern for many women immediately after deportation; 6) women stated feeling lonely and sad. |

| 18 | Robertson et al., 2012b | 1) Thirty-seven percent started shooting drugs after their first migration: marihuana (82%); cocaine (70%); heroin (56%); and crack (36%). |

| 19 | Robertson et al., 2012c | 1) Men with VIH, 0.80%; 2) reported sexually transmitted diseases (22.3%) and the rates of unprotected sex (63.0%); sex with various partners (18.1%), occasional partners (25.7%); sex workers (8.6%). |

| 20 | Ullmann et al., 2011 | 1) Those experienced in migration are 2.11 times more likely to have a cardiac disease (p < 0.01), 2.19 times more prone to emotional /psychiatric disorders (p < 0.01), 1.38 times likely to be obese (p < 0.05), and 1.32 times likely to be a smoker (p < 0.05) than nonimmigrants. |

| 21 | Ojeda et al., 2011 | 1) Use of drugs before migration; 2) use of drugs in the U.S.; 3) shooting drugs in the U.S.; 4) criminal justice system and experiences using substances; 5) drug use and deportation; 6) changes noticed in drug use after deportation; 7) impact of deportation on social relationships, wellbeing, and drug use. |

| 22 | Borges et al., 2009 | 1) Seventy-point-five percent of migrants was more likely to having drunk alcohol, smoking marijuana, or inhaling cocaine at least once, and during the last 12 months a higher probability of developing disorders from the use of addictive substances. |

| 23 | Sowell et al., 2008 | 1) Social isolation, lack of knowledge, denial and machismo are related with having HIV. |

Source: Own elaboration.

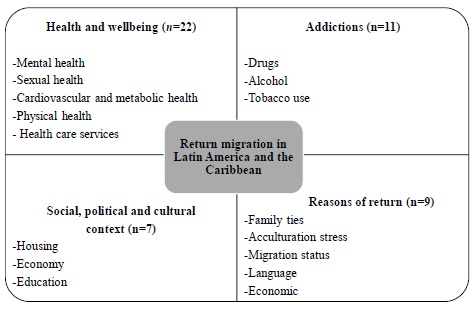

Content analysis identified four main topics: 1) health care and welfare; 2) addictions; 3) social, political, and cultural context; 4) reasons of return (see Figure 2).

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 2 Categories of Return Migration in Latin American and Caribbean Countries

Health and Welfare

Mental health is one of the main lines in return migration; it considerably increases psychiatric problems (Waldman, Wang, & Oh, 2019) as well as mental disorders (Bojorquez et al., 2015; Ulmann, Goldman, & Massey, 2011). The most common mental health problems of return migrants are anxiety (experienced as nervousness and tension), sadness, sleep problems, and suicidal thinking (Bojorquez et al., 2015); depression (Fernández et al., 2018; Pinedo et al., 2018); angst from the challenges posed by return migration (Canedo & Angel, 2019; Duncan, 2015); sadness related to the return due to the separation from their children and other family members (Bojorquez et al., 2015; Robertson et al., 2012a; Robertson, et al., 2012b); solitude, declarations of feeling lonely and sad after deportation because of family separation (Robertson, et al., 2012c); social isolation (Sowell, Holtz, & Velasquez, 2008); guilt when they return to Mexico and leave their family behind (Ruth & Estrada, 2019); resentment and shame (Ojeda et al., 2011); and, lack of psychological housing, that is to say, feelings of not belonging to the country of origin (Negy et al., 2014). It is worth pointing out that some authors have attributed these mental health problems to the problem of deportation and post-deportation (Bojorquez et al., 2015; Negy et al., 2014; Ojeda et al., 2011; Pinedo et al., 2018; Robertson et al., 2012a; Robertson et al., 2012b).

From a literature review regarding the return migrants’ sexual health, it was found that they are frequently vulnerable to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (Rangel et al., 2012); nevertheless, no infections are specified. Moreover, sexual health is also affected by HIV in the recipient country (Martinez et al., 2018; Muñoz et al., 2015; Padilla et al., 2018; Rangel et al., 2012; Robertson et al., 2012a; Sowell et al., 2008), so there is a latent risk of transmitting these diseases after returning to their countries; that is to say, they take HIV to their places of origin, a situation that puts in risk the sexual health of the partner that waits for them at home.

The literature puts forward that infection with HIV is significantly related to acculturation stress levels over the acculturation to a new culture (return country) it is more likely to have a higher risk of contracting HIV (Martinez et al., 2018). Moreover, other factors influence the transmission of VIH such as social isolation, solitude, environmental and language barriers, lack of communication and knowledge regarding HIV contagion mechanisms, which makes them look for sexual partners, unprotected sex, multiple and occasional partners, and encounters with female sex workers (Rangel et al., 2012). Likewise, culturally speaking “machismo” plays an important role in the practice or not of safe sex, machismo is strongly tied to decision-making, plus wives have accepted and decided to have sexual intercourse without protection (Sowell et al., 2008).

It is worth pointing out that upon return, individuals with HIV must face difficulties to afford their disease, receive attention and remain healthy, and disclose their disease to their partners, which is a real challenge. Individuals with HIV face a conundrum while accepting, linked to the economic constrains of the new place; they report feelings of impotence and often feel defenseless; on the other side, women admit they are not able to openly speak about this topic with their spouses due to the cultural unacceptability and taboos entailed in this issue (Sowell et al., 2008).

Some other problems less frequently identified in the population that directly affect cardiovascular and metabolic health are hypertension (Fernández et al., 2018), obesity (Ullmann et al., 2011), and cardiac diseases (Ullmann et al., 2011); that is to say, the experience of migrating implies the possibility of these diseases to appear.

Migrants who decide to voluntarily return report physical limitations, which increase as age does. It is worth pointing out that health deteriorates once migrants are at their home country because of the difficulties experienced over their adaption processes and deplorable employment conditions in the recipient country. Moreover, migrants return because of a forced situation, they are less likely to receive health care coverage, as reinsertion in society and labor market tends to be difficult, the same agency would oversee providing health care coverage (Canedo & Angel, 2019).

Addictions

The consumption of toxic substances, “illegal drugs” such as marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, and crack are frequently reported after deportation (Borges et al., 2009; Horyniak et al., 2017; Ojeda et al., 2011; Pinedo et al., 2018; Robertson et al., 2012a; Robertson, et al., 2012b) by returning migrants, who receive pharmacologic treatment after deportation and integration into treatment programs in Mexico and the U.S. (Robertson et al., 2012c). It is worth mentioning that the most frequent reasons for deportation such as arrests, breaking their parole, and having a record of unauthorized entries into the U.S.; criminal charges from lesser charges on drug possession to armed robberies: car theft and mugs (Robertson et al., 2012a).

Moreover, the importance of the migrants’ context in the consumption of illegal substances in the recipient country was demonstrated (Robertson et al., 2012a). In like manner, the excessive consumption of alcohol is pointed out, the use of alcoholic substances is more prevalent among the migrant population that returns in comparison with the general population, immediate resource in their settlement process (Borges et al., 2009; Robertsonet et al., 2012b); also, the consumption of tobacco is more frequent as compared with the community after deportation (Ullmann et al., 2011).

Finally, the consumption of toxic and harmful substances for the health of the migrants who return is frequently declared a defense mechanism to deal with the emotional consequences brought along by migration processes, which directly affect social relationships and their wellbeing (Ojeda et al., 2011).

Social, Political, and Cultural Context

The economic crisis proper to the place of origin and the lack of supportive networks also become challenges for those returning from abroad. In many cases, return migrants must start a life from scratch and look for opportunities, mostly limited by conditions proper to the developing countries of origin (Fernández et al., 2018; Padilla et al., 2018; Zapata et al., 2018). Moreover, on other occasions, returned migrants face precarious housing conditions and limited access to public services (e.g., drinking water, sewer, and sanitary systems) (Fernández et al., 2018). The lack of education of return migrants is a visible factor in the literature, which shows that labor is more important than schooling, as most only hold secondary education (Muñoz et al., 2015; Sowell et al., 2008).

Reasons for Returning

The main causes of return referred to in the articles are:

Difficulty to remain in the recipient country evinced by acculturation stress the difficulty to adapt to the culture (Martinez et al., 2018; Negy et al., 2014; Vega & Hirschman, 2019).

Family bonds, as there is a higher probability of return migration because of missing the family; that is to say, they have bonds with spouses and children in the country of origin, who are waiting for them (Vega & Hirschman, 2019; Arenas et al., 2015).

Problems with their migration status; that is to say, their status is not legal, reason why they decide to return to their country of origin (Vega & Hirschman, 2019).

Lack of command of the foreign language, i.e., English speakers are significantly less prone to return in comparison with those who seldom speak English or do not at all (Arenas et al., 2015).

Economic characteristics, it has been reported that once migrants reach their goals (e.g., building a house, buying land), they are likely to return to their country of origin (Arenas et al., 2015; Vega & Hirschman, 2019).

Discussion

The goal of this scoping review was to gather the available empirical evidence to ascertain the scope and nature of migrants that return to their countries of origin in Latin America and the Caribbean. After reviewing the literature, return migration is a poorly explored topic in transnational migration. The main gaps are voluntary return migration, and migration return inside Latin American and Caribbean countries; research on migrants from countries other than the United States, and forced return migration in caravans is also limited; also, literature on people who migrated as children and would return after being abroad for more than a decade (dreamers); last, though not least, research works on the impact the return of migrants has on economic, political, cultural and family schemas in their countries, and participatory-action, longitudinal, and intervention studies. The latter is surprising, as many of the studies report mental and sexual health problems among return migrants in their countries of origin.

There are groups of migrants whom the literature on return migration pays little attention; such is the case of Venezuelan migrants who return to their country after living in Colombia or Peru. In the same way, people who emigrated in childhood and returned as adults. For instance, presently, more than 4 million Venezuelans are living abroad, most of which lives in Latin America and the Caribbean; the number of Venezuelan migrants in Colombia, Peru, and Chile surpasses two million people (UNHCR, 2019); however, Colombia reported that only during the Covid-19 pandemic, at least 52 thousand Venezuelans voluntarily returned to their country (Acosta, Cobb, & Gregorio, 2020).

In like manner, the Pew Research Center (López & Krogstad, 2017) reported there are about 800 thousand people under Differed Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in the U.S. Nevertheless, owing to changes in the U.S. migration policies, it is estimated that some 400 individuals who lost their DACA status have been deported since the beginning of the program (Jarvie, 2017). Due to the above, the lack of attention in the literature to dreamers in return migration is surprising. Therefore, it is suggested to focus future research works on scarcely analyzed social groups. This is because most Latin American and Caribbean countries share similar social, economic, and political structures, which may trigger a different situation for dreamers who return from a developed country. It is important to underscore that these figures could be higher since in both cases, they only account for one reason for returning (voluntary or deportation) and from one host country (Colombia or the U.S.).

Very few of the studies in this SR analyze the impact return migration has on economic, political, cultural, and family schemas in the country of origin. For example, research works delve into gender relationships in reunified couples and the effects on family economies. Similarly, it is worth deepening into the contrast of experiences as regards lifestyles, labor, ecological habits, and daily satisfaction means abroad and domestically (Martínez, Monterrubio, & Burstein, 2017). Substantiated on global estimations of about 193 million relatives that were left behind in their places of birth by a migrant worker, which might hint that these individuals return and reintegrate into their families, communities, and societies (OIM, 2019).

The literature mentions that it is the male migrants who experienced this form of migration in Latin America and the Caribbean, showing sociodemographic and family aspects (Cerrutti & Maguid, 2016). Parreñas (2005) describes certain characteristics such as the support that offer male migrants in household activities after returning. However, other authors have found that men retake their gender role, which is established by the society and patriarchal culture of these social groups (Ullah, 2017). Regarding labor reinsertion, whether successful or unsuccessful, it does not exclusively depend on the reasons and means of return, but also on the time they lived abroad, experiences, interaction with the native society, financial situation, plus the context in their native country (Solís, 2018). Evidence has also stated that returning men are less likely to find a job and they frequently return with unfavorable health conditions (Arenas et al., 2015; Gitter, Gitter, & Southgate, 2008).

Return migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean frequently hire in precarious labor activities with low wages or else employ themselves (Franco & Granados, 2018). These situations are effects of political and economic changes faced by both ejecting and recipient countries. This should be relevant for States and welfare decision-makers for a sizeable part of return migrants are youth. The possibility that returning migrants become entrepreneurs in their countries is associated with multiple intersections such as being acquainted with other entrepreneurs, their perception on entrepreneurship opportunities in the country, self-confidence to start a firm, as well as gender, age, schooling, savings, and communication with their place of origin while abroad and the context (period) in which return takes place (Tovar et al., 2018).

The findings of this exploratory systematic review disclose constant affectations to the mental and sexual health and addictions of the migrants who return from abroad. However, there are very few intervention studies and public health care policies to address these issues. HIV prevention programs have demonstrated effectiveness on the migrant population; for example, a meta-analysis found that interventions on safe sex and changes in attitudes toward HIV produced favorable results in the prevention of the disease (Zhang et al., 2018). There are similar data on the benefits of interventions for mental health aimed at migrants, for instance, gaining confidence to ask for health care services and adhering to medical treatments have had important results (Peterson et al., 2020).

In terms of public and health care policies, IOM (2020) recommends close collaboration between origin and destination countries so that the migrants’ return and reinsertion is linked with the social, economic, family and health context of the place. Furthermore, the lack of longitudinal studies is noticed, which would enable assessing health problems over a lengthy period, and participatory action research projects, in which research subjects continuously contribute along the process. The latter has a function to sensitize the participants to develop strategies to improve their quality of life.

Finally, it is essential that origin countries include migrants abroad and returning as key population in relation with sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. In the case of Mexico, Secretaría de Salud [Health Secretariat] and Centro Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del VIH y el SIDA (2018) [National Center for Prevention and Control of HIV and AIDS], considered more than five key populations in risk of acquiring STD or HIV, including men who have sex with other men, sex workers and their clients. However, they did not include migrants, despite Mexico is a country with a noticeable domestic, international, circular, transit, destination, and return migration.

In the face of this, researchers have suggested studying return migration from intersectionality (Fernández et al., 2020), which is a theoretical framework that allows examining oppression and disadvantage systems in vulnerable populations. In this way, researchers must take a critical stance to analyze the sociopolitical, cultural, and family context of migrants who return to their countries of origin.

Limitations and Strengths

This scoping review has limitations and strengths. The present analysis followed a systematic and transparent process to offer an overview of the extension and amount of available research on return migration in Latin America and the Caribbean and identify knowledge gaps and future research project needs. Moreover, studies were carefully chosen in function of predefined inclusion criteria and reviews by experts. Even though a systematic search was carried out in various databases, extending the search to more databases might have provided us with a broader and more detailed panorama of the phenomenon. Likewise, excluding languages different from English and Spanish left studies published in other languages behind. Owing to the nature of the systematic exploratory review of providing an overview of a certain topic, the details of the analyzed works are not approached in this article.

Conclusion

This scoping review provides us with an overview of the empirical literature on return migration to Latin American and Caribbean countries, as well as identifying knowledge gaps. From the analysis of 23 articles on this phenomenon, it is concluded that researchers usually focus on forced return migration from the U.S. to Mexico. People who return to their places of origin face economic, political, and health unfavorable conditions. In this sense, it is suggested that governments in ejecting countries, in collaboration with recipient ones, develop social and family reinsertion programs for returning migrants. The findings of this scoping review comprise the need to design research works to approach this population’s health care problems. Finally, researchers, sponsors, and health authorities in the origin countries are expected to consider the recommendations discussed in the present article for when they must decide on the design of future research projects related to return migration.

Translation: Luis Cejudo Espinosa

Referencias

Acosta, J., Cobb, J. y Gregorio, D. (12 de mayo de 2020). Colombia says over 52,000 venezuelans return home, cites lockdown, U.S News. Recuperado de https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2020-05-12/colombia-says-over-52-000- venezuelans-return-home-cites-lockdown [ Links ]

Arenas, E., Goldman, N., Pebley, A. y Teruel, G. (2015). Return Migration to Mexico: Does Health Matter?. Demography, 52(6), 1853-1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0429-7 [ Links ]

Aruj, R. (2008). Causas, consecuencias, efectos e impacto de las migraciones en Latinoamérica. Papeles de población, 14(55), 95-116. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-74252008000100005 [ Links ]

Azose, J. y Raftery, A. (2019). Estimation of emigration, return migration, and transit migration between all pairs of countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences-PNAS, 116(1), 116-122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1722334116 [ Links ]

Bojorquez, I., Aguilera, R., Ramirez, J., Cerecero, D. y Mejía, S. (2015). Common Mental Disorders at the Time of Deportation: A Survey at the Mexico-United States Border. Journal of Inmigrant and Minority Health, 17(6), 1732-1738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014- 0083-y [ Links ]

Bonilla, G. (2020). La migración guatemalteca hacia los Estados Unidos y su costo social. Ciencias sociales y humanidades, 7(1), 51-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.36829/63CHS.v7i1.959 [ Links ]

Borges, G., Medina-Mora, M. A., Orozco, R., Fleiz, C., Cherpitel, C. y Breslau, J. (2009). The Mexican Migration to the United States and Substance use in Northern Mexico. Addiction, 104(4), 603-611. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02491.x [ Links ]

Cabieses, B., Gálvez, P. y Ajraz, N. (2018). Migración Internacional y Salud: El aporte de las teorías sociales migratorias a las decisiones en salud pública. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 35(2), 285-291. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2018.352.3102 [ Links ]

Canedo, A. y Angel, J. (2019). Aging and the Hidden Costs of Going Home to Mexico. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 34(4), 417-437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-019-09379-3 [ Links ]

Cataño, S. y Morales, S. (2015). La migración de retorno. Una descripción desde algunas investigaciones latinoamericanas y españolas. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 6(1), 89-112. https://doi.org/10.21501/22161201.1424 [ Links ]

Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía (CELADE). (2006). Migración Internacional de Latinoamericanos y Caribeños en Iberoamérica: características, retos y oportunidades. En Encuentro Iberoamericano sobre Migración y Desarrollo, Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Cerrutti, M. y Maguid, A. (2016). Crisis económica en España y el retorno de inmigrantes sudamericanos. Migraciones Internacionales, 8(30), 155-189. https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v8i3.618 [ Links ]

Crosa, Z. (2015). Migraciones latinoamericanas. Procesos e identidades: el caso uruguayo en Argentina. Polis Revista Latinoamericana, 14(41), 371-394. Recuperado de https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-65682015000200023 [ Links ]

Duncan, W. L. (2015). Transnational Disorders: Returned Migrants at Oaxaca’s Psychiatric Hospital. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 29(1), 24-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12138 [ Links ]

Fernández, H. (2020). Transnational migration and Mexican women who remain behind: An intersectional approach. PLOS ONE, 15(9), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238525 [ Links ]

Fernández, H., Gómez, T. y Pérez, M. (2020). Intersección de pobreza y desigualdad frente al distanciamiento social durante la pandemia COVID-19. Revista Cubana de Enfermería, 36, 1- 15. Recuperado de http://www.revenfermeria.sld.cu/index.php/enf/article/view/3795 [ Links ]

Fernández, H., King, K. y Enríquez, C. (2020). Revisiones Sistemáticas Exploratorias como metodología para la síntesis del conocimiento científico. Enfermería Universitaria, 17(1), 87- 94. https://doi.org/10.22201/eneo.23958421e.2020.1.697 [ Links ]

Fernández, H., Salma, J., Márquez, P. y Bukola, S. (2020). Left-Behind Women in the Context of International Migration: A Scoping Review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 31(6), 606-616. [ Links ]

Fernández, J., Vásquez, A., Flórez, V., Rojas, M., Luna, K., Navarro, E., Acosta, J. y Rodríguez, D. (2018). Lifestyles and health status of migrants in a settlement of Barranquilla, Colombia 2018. Revista de Salud Pública, 20(4), 530-538. https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.V20n4.75773 [ Links ]

Franco, L. M. y Granados, J. A. (2018). Migración de retorno y el empleo en México. En S. De la Vega y C. Ken (Coords.), Desigualdad regional, pobreza y migración (pp. 720-742). Repositorio Universitario RU-Económicas-UNAM/AMECIDER. [ Links ]

Gitter, S., Gitter, R. y Southgate, D. (2008). The Impact of Return Migration to Mexico. Estudios Económicos, 23(1), 3-23. Recuperado de https://estudioseconomicos.colmex.mx/index.php/economicos/article/view/140 [ Links ]

Horyniak, D., Pinedo, M., Burgos, J. L. y Ojeda, V. D. (2017). Relationships between Integration and Drug use among Deported Migrants in Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(5), 1196-1206. [ Links ]

Hsieh, H. y Shannon, S. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. [ Links ]

Jarvie, J. (19 de abril del 2017). Deportations of ‘Dreamers’ who’ve lost protected status have surged under Trump. Los Angeles Times. Recuperado de https://www.latimes.com/nation/la- na-daca-deportations-20170419-story.html [ Links ]

López, G. y Krogstad, J. (2017). Key facts about unauthorized immigrants enrolled in DACA. Pew Research Center. Recuperado de https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/25/key-facts-about-unauthorized-immigrants-enrolled-in-daca/ [ Links ]

Lozano, F. y Martínez, J. (2015). Retorno en los procesos migratorios de América Latina: conceptos, debates, evidencias. Río de Janeiro, Brasil: ALAP Editor. [ Links ]

Martine, G., Hakkert, R. y Guzmán, J. (2001). Aspectos Sociales de la Migración Internacional: Consideraciones Preliminares. Notas de Población, 28(37), 163-193. [ Links ]

Martinez, A., Zhang, X., Rangel, M., Hovell, M., Gonzalez, J., Magis, C. y Guendelman, S. (2018). Does Acculturative Stress Influence Inmigrant Sexual HIV Risk and HIV Testing Behavior? Evidence from a Survey of Male Mexican Migrants. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(4), 798-807. [ Links ]

Martínez, V., Monterrubio, S. y Burstein, J. (2017). Ambivalencias de la migración y el retorno en contextos rurales de Chiapas: Entre las multas y el bien común. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(33). https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v9i33.250 [ Links ]

Micolta, A. (2005). Teorías y conceptos asociados al estudio de las migraciones internacionales. Trabajo Social, (7), 59-76. Recuperado de https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/tsocial/article/view/8476 [ Links ]

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. y The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [ Links ]

Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A. y Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [ Links ]

Muñoz, F., Servin, A., Garfein, R. S., Ojeda, V. D., Rangel, G. y Zuñiga, M. L. (2015). Deportation History among HIV-Positive Latinos in Two US-Mexico Border Communities. Journal of Inmigrant and Minority Health, 17(1), 104-111. [ Links ]

Navarro, J. C., Ayvar, F. J. y Zamora, A. I. (2016). Desarrollo económico y migración en América Latina, 1980-2013: Un estudio a partir del Análisis Envolvente de Datos. TRACE, Procesos Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, (70), 149-164. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S0185-62862016000200149&script=sci_abstract [ Links ]

Negy, C., Reig-Ferrer, A., Gaborit, M. y Ferguson, C. (2014). Psychological Homelessness and Enculturative Stress among US-Deported Salvadorans: A Preliminary Study with a Novel Approach. Journal of Inmigrant and Minority Health, 16(6), 1278-1283. [ Links ]

Ojeda, V., Robertson, A., Hiller, S., Lozada, R., Cornelius, W., Palinkas, L., Magis, C. y Strathdee, S. (2011). A Qualitative View of Drug Use Behaviors of Mexican Male Injection Drug Users Deported from the United States. Journal of Urban Health, 88(1), 104-117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9508-7 [ Links ]

Organización de Naciones Unidas (ONU). (2020). Migración, datos sobre migración. Recuperado de https://www.un.org/es/global-issues/migration [ Links ]

Organización Internacional de Migración (OIM). (2019). ¿Quién es un migrante?. Recuperado de https://www.iom.int/es/quien-es-un-migrante [ Links ]

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). (2020). Return migration. Recuperado de https://www.iom.int/es [ Links ]

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos (OCDE). (2017). Interacciones entre políticas públicas, migración y desarrollo. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276710-es [ Links ]

Padilla, M., Colón-Burgos, J. F., Varas-Díaz, N., Matiz-Reyes, A. y Parker, C. M. (2018). Tourism labor, embodied suffering, and the deportation regime in the Dominican Republic. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 32(4), 498-519. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12447 [ Links ]

Parreñas, R. S. (2005). The gender paradox in the transnational families of filipino migrant women. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 14(3), 243-268. [ Links ]

Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. y Khalil, H. (2017). Scoping reviews. En E. Aromantaris y Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, (pp. 1-28). Recuperado de https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Micah- Peters/publication/319713049_2017_Guidance_for_the_Conduct_of_JBI_Scoping_Reviews/links/59c355d40f7e9b21a82c547f/2017-Guidance-for-the-Conduct-of-JBI-Scoping- Reviews.pdf [ Links ]

Peterson, C., Poudel-Tandukar, K., Sanger, K. y Jacelon, C. S. (2020). Improving mental health in refugee populations: A review of intervention studies conducted in the united states. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(4), 271-282. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1669748 [ Links ]

Pinedo, M., Burgos, J., Zuñiga, M., Pérez, R., Macera, C. y Ojeda, V. (2018). Deportation and mental health among migrants who inject drugs along the US-Mexico border. Global Public Health, 13(2), 211-226. [ Links ]

Rangel, M., Martinez-Donate, A., Hovell, M., Sipan, C., Zellner, J., Gonzalez-Fagoaga, E. y Magis-Rodriguez, C. (2012). A Two-Way Road: Rates of HIV Infection and Behavioral Risk Factors Among Deported Mexican Labor Migrants. AIDS and Behavior, 16(6), 1630-1640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0196-z [ Links ]

Robertson, A. M., Rangel, M. G., Lozada, R., Vera, A. y Ojeda, V. D. (2012). Male injection drug users try new drugs following U.S. deportation to Tijuana, Mexico. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 120(1-3), 142-148. [ Links ]

Robertson, A., Lozada, R., Pollini, R., Rangel, G. y Ojeda, V. (2012). Correlates and Contexts of U.S. Injection Drug Initiation Among Undocumented Mexican Migrant Men Who Were Deported from the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 16(6), 1670-1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0111-z [ Links ]

Robertson, A., Lozada, R., Vera, A., Palinkas, L., Burgos, J., Magis, C., Rangel, G. y Ojeda, V. (2012). Deportation Experiences of Women Who Inject Drugs in Tijuana, Mexico. Qualitative Health Research, 22(4), 499-510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311422238 [ Links ]

Ruth, A. y Estrada, E. (2019). DACAmented Homecomings: A Brief Return to Exica and the Reshaping of Bounded Solidarity Among Mixed-Status Latinx Families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 41(2), 145-165. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Salud, Centro Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del VIH y el SIDA. (2018). Informe nacional del monitoreo de compromisos y objetivos ampliados para poner fin al sida (Informe GAM). México: Autor. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/MEX_2018_countryreport.pdf [ Links ]

Solís, L. (2018). Labor Reintegration of Return Migrants in Two Rural Communities of Yucatán, Mexico. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(35). http://dx.doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v9i35.416 [ Links ]

Sowell, R. L., Holtz, C. S. y Velasquez, G. (2008). HIV Infection Returning to Mexico With Migrant Workers: An Exploratory Study. Journal of the Association of nurses in AIDS Care, 19(4), 267-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2008.01.004 [ Links ]

Tovar, L. M., Victoria, M. T., Tovar, J. R., Troncoso, G. y Pereira, F. (2018). Factores asociados a la probabilidad de emprendimiento en migrantes colombianos que retornan a Colombia. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(34). https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v9i34.366 [ Links ]

Ullah, A. A. (2017). Male Migration and ‘Left-behind’ Women: Bane or Boon? Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 8(1), 59-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425316683862 [ Links ]

Ulmann, S., Goldman, N. y Massey, D. (2011). Healthier before they migrate, less healthy when they return?. The health of returned migrants in Mexico. Social Science & Medicine, 73(3), 421-428. [ Links ]

UNHCR. (7 de junio de 2019). Refugees and migrants from Venezuela top 4 million: UNHCR and IOM. UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency. Recuperado de https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2019/6/5cfa2a4a4/refugees-migrants-venezuela-top-4- million-unhcr-iom.html [ Links ]

Vega, A. y Hirschman, K. (2019). The reasons older immigrants in the United States of america report for returning to Mexico. Ageing and Society, 39(4), 722-748. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17001155 [ Links ]

Waldman, K., Wang, J. y Oh, H. (2019). Psychiatric problems among returned migrants in Mexico: Updated findings from the mexican migration project. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(10), 1285-1294. [ Links ]

Zapata, C., Agudelo, A., Cardona, D. y Ronda, E. (2018). Health Status and Experience of the Migrant Workers Returned from Spain to Colombia: A Qualitative Approach. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(6), 1404-1414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0684-3 [ Links ]

Zhang, R., Chen, L., Cui, Y. y Li, G. (2018). Achievement of interventions on HIV infection prevention among migrants in China: A meta-analysis. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 15(1), 31-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2018.1451773 [ Links ]

Received: September 21, 2020; Accepted: January 26, 2021

texto en

texto en