Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Migraciones internacionales

versão On-line ISSN 2594-0279versão impressa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.12 Tijuana Jan./Dez. 2021 Epub 24-Jan-2022

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2382

Papers

Remittances and Economic Agency of University Students in the Mezquital Valley

1 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Escuela Superior de Actopan, Mexico, huertamx@hotmail.com

The article’s objective is to analyze the economic agency acquired by university students through the international remittances support network. During September and October 2019, five in- depth interviews were conducted with female law students from the Actopan Higher School of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo. Young women’s households receive remittances whose function is to help them economically, a network built through the family connection with their maternal uncles. The student’s mothers are sorors which allows young women to obtain economic agency. This analysis contributes to the knowledge about one of the effects of remittances on households in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico. The results of the study only focus on one region of the country.

Keywords: 1. remittances; 2. economic agency; 3. sisterhood; 4. Mezquital Valley; 5. Mexico

El objetivo de este artículo es analizar la agencia económica que adquieren las estudiantes universitarias a través de la red de apoyo de las remesas internacionales. En los meses de septiembre y octubre de 2019 se realizaron cinco entrevistas en profundidad con mujeres estudiantes universitarias de la Licenciatura en Derecho, de la Escuela Superior de Actopan de la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. Los hogares de las jóvenes perciben remesas, cuya función es auxiliarlas económicamente, con lo que se configura una red construida a través del vínculo familiar con los tíos maternos. Las madres de las estudiantes son sororas con sus hijas, lo que les permite a las jóvenes obtener agencia económica. Este análisis contribuye al conocimiento en torno a uno de los efectos de las remesas en los hogares del Valle del Mezquital, México. Los resultados solo corresponden a una región del país.

Palabras clave: 1. remesas; 2. agencia económica; 3. sororidad; 4. Valle del Mezquital; 5. México

Introduction

In Mexico, women aged 15 and over study an average of 9 years, the average for men being 9.3. In general, the population of both sexes finishes basic education, however, women do so with a 0.3% lag (National Women’s Institute (INMUJERES, acronym in Spanish), 2015). According to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), out of every 100 people who enroll in primary education in the country, 21 complete a bachelor’s degree; Likewise, Mexico is the country with the lowest percentage (17%) of people between ages 25 and 64 who have attended university, when compared to the average of the member countries (37%) (Valadez, 2018). On the other hand, “the proportion of young adults (25 to 34 years old), who completed higher education is 23% in 2018, below the OECD average (44%)” (OECD, 2019, p. 2).

According to figures from the Mexican Youth Institute (IMJUVE, acronym in Spanish), in Mexico, there are 37.5 million young people between ages 12 and 29 (10.8 million are between ages 15 and 19 and 10.7 million between ages 20 and 24), representing 31.4 % of the population. Nearly half of the young people in Mexico live in poverty (Redacción Animal Político, 2018), and so economic conditions are a crucial factor for Mexicans to enroll and stay in Universities.

On the other hand, an amendment was made to the third article of the constitution in May 2019, setting forth higher education as a human right that must be guaranteed; therefore, this educational level is now mandatory (Political Constitution of the United Mexican States, 2019, Third Constitutional Article, amended). However, for the 2018-2019 school year, the total coverage of higher education in the schooled modality (not including postgraduate studies), is only 33.9%. In this regard, the statistics for the same school year show that the total coverage in the state of Hidalgo is 38.8%, this percentage placing it above the national average; also, women reach 39.7% and men 37.8% (SEP, 2019). In addition, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, acronym in Spanish), Hidalgo ranks as the sixth state with the lowest average income per household, this state of things being stressed in its rural areas (the mean national average quarterly income for families is 49,610 MXN, yet the average income of rural families in Hidalgo is 29,744 MXN) (Ameth, 2019). In this sense, women in the state of Hidalgo access higher education to a greater extent than men do, the economy becoming a key factor for them to remain in university, which is why it is essential to investigate the economic strategies they deploy to stay within the educational system.

To study the economic dimension of rights is a priority in current times (Cruz, 2019). It should be noted that the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development aims at establishing the structural conditions that would allow for a culture of equality. For its part, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has set forth economic autonomy as one of the three strategic dimensions for women’s autonomy, defining it as one that “[... ] is linked to the possibility of controlling assets and resources” (UN & ECLAC, 2016, p. 36). However, in the words of Howard-Hassmann (2011), women’s economic rights are precariously protected in both developed and developing countries.

On the other hand, Mexico’s rural areas have experienced conditions of poverty, violence, high birth rates, and the impoverishment of agricultural activities throughout the 20th century; to this should be added situations of unemployment, impunity, and economic crisis, and so this population finds migrating to the United States an alternative to their economic precariousness (Durand, 2016). It should be taken into account that:

The migratory process between Mexico and the United States is a centuries-old traditional social phenomenon [… ] that takes place between neighboring countries sharing a border spanning more than 3,000 kilometers. [… ] No other migration flow to the United States from a single country has lasted more than 130 years (Durand, 2016, pp. 18-19).

Migration from central Mexico, wherein the state of Hidalgo is located, increased in the decades of the eighties and nineties, migration being massive in the latter decade; in previous years the population of the said area used to migrate to Mexico City. However, the contraction of the labor market caused this internal migration to change into international migration (Durand, 2016).

Massey (2016) stated that the current migration of Mexicans to the United States is not massive as it was in previous decades. Under the Bracero program of 1950, each year about half a million Mexicans legally entered the United States to work, of which 10% obtained a permanent residence visa. From the 1950s to the 1970s, half a million Mexicans acquired legal visas, both temporary, and permanent. In 1993, the militarization of the United States-Mexico border increased pace; consequently, the migration of Mexicans decreased since 2000, and so the massive migration of undocumented Mexicans that took place during the 1980s and 1990s did not repeat. Therefore, most of the remittances that are sent to Mexico come from people who migrated in the non-recent past.

Due to all of the above, Mexico is in third place among the countries with the highest entry of remittances (World Bank, 2019). And the state of Hidalgo is in 14th place in the entry of remittances among the 32 Mexican states (Banco de México, n.d.).

The UN and ECLAC (2016) propose that the impact of remittances should be analyzed not only in relation to the macroeconomy but also as it pertains to the dynamics of the family economy.

Giorguli and Serratos (2009) argue that “6% of young Mexicans are directly exposed to migration through the absence of a family member or by receiving remittances, and 30% live in municipalities with high or very high migratory intensity” (p. 339). Previous studies have focused on the positive effects of international remittances on investment in household education in Mexico (Acosta & Caamal-Olvera, 2017; García & Cuecuecha, 2020; Giorguli & Serratos, 2009; López-Córdova, 2006). As can be inferred, quantitative research on the subject predominates. Yet few studies investigate migration and remittances from a gender perspective (Munster, 2014). A qualitative approach will allow us to understand the subjectivities configured in relation to remittances and the economic agency and university education of women.

Remittances can generate economic agency in those benefiting from them and their family group; the economic agency is “the ability to make independent economic decisions, based on the willingness and the ability to make them” (Htun, Jensenius, & Nelson-Núñez, 2019, p. 199). Therefore, it implies women adopting an active position in the face of limiting situations.

Thus, the purpose of this research is to analyze the economic agency that university students acquire through the support network that revolves around international remittances. For this, five individual and in-depth interviews were conducted with students of the Law Degree of the Actopan Higher School of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, Mexico. We studied remittances as a support network system for young women to be able to stay in university despite their economic precariousness; the data analysis was carried out under a gender perspective, specifically pertaining to sorority, understood as solidarity among women for them to reach better living conditions. This work aims at contributing to migration studies as a reference on the relationship between sorority actions and the destination of remittances in the education of women belonging to areas of high migration flow to the United States, such as the Mezquital Valley, located in the state of Hidalgo. Thus, the originality of this work lies in its contribution to knowledge on the relationship between remittances, gender, economic agency, and higher education, approached from a qualitative methodology.

Contextual framework

The Mezquital Valley is located to the west of the state of Hidalgo, characterized by semi-arid geography; although it has an irrigation system, it only supplies water to one area in the region. As for its population, the Hñahñu indigenous group is representative of the region (Rivera, 2000).

This region stands out for its high international migration flow in the 1990s, which intensified from the year 2000 “[… ] positioning the state in second place among the states with the highest growth rate of migration to the United States” (Scale, 2006, p. 11). From January 1995 to February 2000, 62,160 people from Hidalgo emigrated to that country, of which 48.6% came from the Mezquital Valley, 82.5% men, and 17.5% women (INEGI, 2004). By 2010 “28 municipalities in Hidalgo were identified with high and very high degrees of migratory intensity, 15 of them in the Mezquital Valley” (Quezada, 2018, p. 3). Thus, it is possible that given the dynamics from 30 years ago (characterized by a high migration flow from the Mezquital Valley) a pool of migrants stayed in the United States and throughout that time managed to grow their economy, allowing them to now send remittances to their relatives in Mexico.

Remittances as an economic support network

A support network is defined as “[… ] a well-defined set of actors —individuals [… ]— linked to each other through a social relationship or set of relationships” (Lozares, 1996, p. 108). The network approach understands social structures as constituted by the relationships that link social units, and so its goal is understanding the behavior of the actors based on their position within the structure, this way the various social constraints, opportunities or supports that individuals experience or have access to can be identified (Lozares, 1996).

As in themselves, remittances are “private monetary transfers that migrants make, either across borders or within the same country, to individuals or communities with whom they keep ties” (IOM, 2006, p. 199). Thus, receiving remittances is an economic support network for a sector of the Mexican population. In this regard, Canales and Montiel (2004) point out that remittances serve the purpose of closing gaps of economic inequalities in the families that receive them. Therefore, remittances cause an economic effect in receiving countries, as they allow those households receiving them to circumvent poverty (Orozco, 2013). These resources are generally intended to cover expenses in the following order: sustenance, health, education (Bonilla, 2016; Deere, Alvarado, Oduro, & Boakye-Yiadom, 2015). A lesser percentage is invested in businesses, in the case of Mexico corresponding to 1% (Deere et al., 2015).

In regions characterized by traditional migration to the United States, this activity is more commonly carried out by men, on average from the age of 15, a situation that can encourage women from these communities to enroll in higher education (Sawyer, 2015). In Mexico, a culture of migration has been developed, encouraging migration to the United States among young men, thus in some places said migration is considered a rite of passage derived from non- migrant men imitating those who migrated in the past, and so young men tend to drop out of school due to the aspiration of working in the United States (Kandel & Massey, 2002).

For its part, the OECD points out that “remittances are not linked to a higher level of schooling in most countries” (OECD, 2017, p. 34). Studies confirm that remittances are seldomly invested in education: among receiving families, education is not a priority item for allocating this capital (Airola, 2007; Corona, 2007; Mora & Arellano, 2016; Sawyer, 2015). Research on eleven Latin American countries showed that remittances have a positive effect on attendance to higher education, except in Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic (Acosta, Fajnzylber, & López, 2007).

However, the data in this article cast doubt on the previous statements, since they show that remittances are a key element —either provisionally or permanently— for young women to attend university.

Agency and Economic Rights of University Students

The American Convention on Human Rights (Pact of San José) of 1978, in its chapter II on economic, social, and cultural rights, Article 26, section on progressive development, sets forth the following:

The States Parties undertake to adopt measures, both internally and through international cooperation, especially those of an economic and technical nature, to achieve progressively, by legislation or other appropriate means, the full realization of the rights implicit in the economic, social, educational, scientific, and cultural standards outlined in the Charter of the Organization of American States as amended by the Protocol of Buenos Aires American Convention on Human Rights (Pact of San José, 1978, p. 9).

Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Rights (ESCR) were only recognized relatively recently, and the mechanisms for their effectiveness are still undergoing a process consolidation and development (National Human Rights Commission, Mexico (CNDH, acronym in Spanish), n.d.). These rights include:

The rights to an adequate standard of living, to food, health, water, sanitation, work, social security, adequate housing, education, culture, as well as a healthy environment (CNDH, n.d.).

In this regard, the Mexican government acknowledges economic well-being as one of the human rights of women; consequently, if the aim is to guarantee the human rights of this population, understanding the social structures that condition the family economy and dynamics becomes essential (National Women’s Institute, 2016).

The Ibero-American Convention on the Rights of Youth (International Youth Organization (OIJ, acronym in Spanish), 2008) specifically sets forth in its Article 34 the commitment of the signing countries in terms of developing measures that allow guaranteeing the economic rights of youth in rural and urban areas. Along the same line, Article 29 posits the right to professional training for young people. The principle of interdependence establishes the link between rights in such a way that certain rights have an impact on others, as it happens in this case with young people’s economic rights and those of access to education.

Prior to the above, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), 1976), outlined in its Article 13 the right to equal access to higher education, which must eventually become free; however, this is not an overarching reality, and consequently, students have to make use of social resources such as financial support networks if they are to achieve enrollment in universities. Thus, the exercise of economic rights is essential for young women to hold on to the possibility of staying in the educational system, thus acquiring higher employment qualifications.

Regarding agency, Burkitt (2015) questioned reflexivity as its central element, since in his paradigm agency is assumed as an individual possession, and he argues relationships to be at the core of reflexivity. He posits that agency is a relational phenomenon, which is why it arises from the interdependence resulting from the interactions and joint actions of human beings as a whole, in turn, focused on emotional aspects. According to this paradigm, people never confront the structure by themselves alone, committed as they are in social relationships, and therefore they not only answer to their interests but also the needs of other people. Due to the foregoing, the author defines agency as actions that produce effects on others depending on personal ties involving feelings of loyalty, affiliation, trust, identification, ambivalence, among others. He proposes that social relations be viewed not only as those that allow or constrain agency but also as those that make up structure and agency (Burkitt, 2015).

Specifically, the economic agency “is the ability to make independent economic decisions, based on the willingness and the ability to make them” (Htun et al., 2019, p. 199). Agency implies the actions undertaken to obtain resources and the decisions that are made about them, this empowers people to generate social changes or in their economic condition.

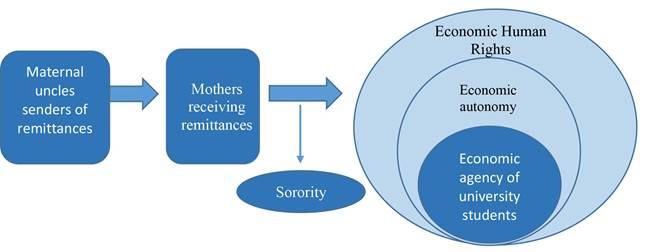

On the other hand, autonomy is essential for the exercise of rights (UN & ECLAC, 2016). Howard-Hassmann (2011) argues that one of the consequences of economic globalization is the greater economic autonomy of women due to the impact on the living standards of millions of them; however, this dynamic also constrains their human rights. This author also establishes an implicit relationship between agency and autonomy, in such a way that without agency and autonomy the exercise of human rights is not possible (see Figure 1).

In the words of Howard-Hassmann (2011), autonomy lies in the ability of a person to make decisions based on their interests, in this case applying to the economic decisions made in families receiving remittances that provide economic agency to university students in the Mezquital Valley region, a state of things that may influence the exercising of economic rights by these women, and their ability to access and/or continue attending higher education institutions.

Source: Own elaboration based on Howard-Hassmann’s theory (2011).

Figure 1 Relationship Between Human Rights, Autonomy, and Agency

It should be clarified that the relationship between autonomy and agency is determined by the women’s country of origin, that is, women’s decisions are constrained by the economic reality of the place where they live (Howard-Hassmann, 2011).

Sorority as a Means to Acquire Economic Agency

Lagarde y de los Ríos (in the Department of Feminism and Diversity of Fuenlabrada, 2013) stated that sorority consists of the support that women provide each other through sisterly collaboration relationships. It is “the alliance of women in the commitment [… ] to create spaces in which women can deploy new life possibilities” (Lagarde y de los Ríos, 2012, p. 486). The same author (2006) pointed out as a practice of sorority, the spreading of the resources that some women enjoy, and so sorority becomes a means of aid among themselves, a pact that allows them to develop. Therefore, sorority is the counterpart to the social hierarchization of women, it is sharing among them as a means to acquire autonomy (Lagarde y de los Ríos, 2009). Sorority as a “voluntary and conscious action,” as a means for women to build their rights together (Lagarde y de los Ríos, 2013, min 36.23 to 36.43).

Methodology

This paper stems from a broader investigation entitled “The economy of university students in the Mezquital Valley.” Sixteen in-depth interviews were conducted with female students of the Law Degree of the Actopan Higher School of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, Mexico. Hereby the content of the interviews with five participants is analyzed, in which remittances were identified as an economic support network (see Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Information of the Participants2

| Participant | Age | Place of legal address in Hidalgo | Semester | Father’s age | Mother’s age | Father’s schooling | Mother’s schooling | Siblings | Father’s occupation | Mother’s occupation | Source of remittance | Scholarship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carmen | 20 | Acaxochitlán | 4º | 42 | 41 | Middle School | Middle School | 4 | Field Worker | Housekeeper | Maternal uncle | Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro |

| Paula | 20 | Ixmiquilpan | 5º | 42 | 39 | Elementary School | Middle School | 2 | Employee | Employee | Maternal uncle | Prospera/ Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro |

| Sara | 21 | Ixmiquilpan | 7º | 64 | 55 | High School | Teacher’s College | 3 | Laborer | Professor | Maternal uncle | Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro |

| Ester | 21 | Tlahuelilpan | 4º | 61 | 54 | Elementary School | College Degree | 2 | Mechanic | Housekeeper | Maternal uncle | Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro |

| Lucía | 21 | Francisco I. Madero | 7º | 48 | 45 | College Degree | High School técnico | 1 | Professor | Housekeeper | Maternal uncle | Prospera/ Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro |

Source: Own elaboration with data provided by the participants.

Actopan Higher School is located in Daxthá, a community in the municipality of Actopan, in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. This school belongs to the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo and was established in 2000. It currently offers degrees in Psychology, Law, Business Creation, and Development, Graphic Design, as well as High School education. The Law student population was selected for this research because it is the degree with the largest enrollment in this educational center, and in which women predominate by 61.3% (Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, 2020).

The sample was selected following inclusion criteria: single women, without children, current students of any semester and shift of the Law Degree, ages from 18 to 24.

Individual interviews were approximately two hours long each and were carried out in September and October 2019. All the young women participated voluntarily and signed informed consent, their names and those of others given in their testimonies have been changed for confidentiality reasons.

The interviews were guided according to the following question: How has your financial situation been since you enrolled in university? These young women were asked to make a timeline accounting for the following: were we to trace a line in time from when you were born until today, who would be there that has supported you financially? Or else, who has paid for your expenses?

All interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed. The data were analyzed by means of the content analysis technique, which aims at understanding how individuals shape reality through language since according to Bardin (2002) meanings are “the main material of content analysis” (p. 33).

The analysis of the collected data reveals five types of support networks that young women partake in through remittances sent by their maternal uncles —who migrated to the United States—, providing them with economic agency: 1) Remittances as a support network aimed directly at the young woman, 2) Remittances as a support network for parents’ labor instability,

3) Remittances as a support network upon the unexpected lack of provision from the father, 4) Remittances as a support network needed due to sporadic provision from the father, and 5) Remittances as a support network upon unexpected expenses at home.

Results

The data in this work show that remittances are a key element —provisionally or permanently— for young women to acquire the economic agency and attend university. A factor benefiting them is the one found by McPherson, Smith-Loving, and Brashears (2006): women, compared to men, have a significantly higher number of relatives in their social networks. Given this, mothers make use of family support networks to obtain remittances, thus encouraging their daughters to attend university. In this case, they fall into the category of “home related to migration,” a term used by the Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF) in the 2005 Household Survey on Migration in the State of Hidalgo (Rivera & Quezada, 2011).

Mothers of migrants are the ones receiving the remittances, for the most part, followed by spouses (Bonilla, 2016). In Latin America, patterns have been found showing that single or married migrants (who do not trust their wives) send remittances to their mothers. Married men commonly send them to their wives (Deere, Alvarado, Oduro, & Boakye-Yiadom, 2015).

Consanguineous kinship ties are organized in kinship lines, formed by a consecutive series of degrees, among which the following can be identified:

Ascending line. It links someone with those from whom it is directly descended. Example: Mother or father, it is the existing link by consanguineous affiliation with the man or woman of whom one is a child.

Collateral line. The series of degrees existing between people who have a common ancestor, without descending one from the other. Example: sibling, […] niece/nephew, is the existing collateral line link with the daughter or son of a sister or brother.

(INEGI, 2012, pp. 7-8).

“In the equal collateral line [… ] siblings [… ]. In the unequal collateral one [… ] the uncles and nephews” (Federal Civil Code, article 156, section III, 2020, p. 21). The kinship link between a migrant and his mother corresponds to the ascending line. The kinship link between a migrant and his sister corresponds to the equal collateral line. The kinship link between the migrant uncle and his niece corresponds to the unequal collateral line.

Although the kinship link between the migrant uncle and the niece is not a direct line (as is the case with the children of migrant parents), young women still benefit from receiving remittances over unequal collateral lines, from the economic support that their mothers get from their brothers (migrants in the United States). Although their finances are not entirely dependent on the remittances received, these can indeed influence a certain economic agency that allows young women to continue attending university. Burkitt (2015) argues that agency develops in social relations, which is evident in the support network established by the maternal uncles of the university students, where the interrelation of three actors is implied: the uncles, the mothers of the young women, and the students themselves. Sorority plays a fundamental role in this support network since it is an alliance that mothers establish with their daughters and allows young women to obtain the benefit of the remittances that their mothers receive; in this way, they can acquire economic agency. The support network fostered by remittances and the sorority of mothers as generators of economic agency and therefore of economic autonomy, and the consequent exercise of economic rights among young university students (see Figure 2).

Source: Own elaboration based on Howard-Hassmann’s theory (2011).

Figure 2 Support Network Through Remittances, Sorority, and Economic Agency

Below are five modalities in which we identified this dynamic of economic support for university students in the Mezquital Valley.

Remittances as a Support Network Aimed Directly at the Young Woman

As an economic support network, remittances for migrants become a means that allows them to reinforce, from time to time, a prestigious position vis-à-vis their extended family living in Mexico, specifically if it benefits the members of the third generation of relatives, such as nieces:

When it’s my birthday, my uncle in the United States sends me money, sometimes both do, because I only have two uncles. One of them gives everyone money because he does not have children, he does not have a wife, he does not have a family, so he feels he has a lot of money, as he works there, so he manages to send me two thousand to three thousand pesos every year, ever since I turned 15 (Paula, personal communication, September 12, 2019).

Another participant receives remittances regularly from one of her uncles, and so she can count on that money throughout the year; it should be noted that her mother worked as a teacher until she was 7 years old and left the working market upon falling ill with diabetes.

Two uncles, my mother’s brothers [work] in construction in the United States, [they send money since I was born] about four times a year, my mother receives the money, well, it is intended for me, but they send it to her [... ] (Ester, personal communication, September 23, 2019).

The fact that the maternal uncles are not day laborers and work in construction allows them to obtain higher salaries, as pointed out by Solís and Fortuny (2010), and so their employment

status adds to the support network they establish to aid their nieces in the place of origin. In this way, remittances are a permanent complement in the economy of young university students, granting them economic autonomy to a certain extent.

Remittances as a Support Network for Parents’ Labor Instability

Franco (2001) identified that in Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo, remittances are invested in businesses once the migrant has managed to cover the basic expenses of the household to which the resources are allocated. This state of things is illustrated by the participant quoted next, in which case the maternal uncle capitalizes through remittances the food business managed by the student’s mother.

My uncle —I will always be grateful to him because we have succeeded thanks to him— [… ] I was seven years old when the business thing came up. My mom was always changing shifts [she was a cook in a restaurant] [… ]. My dad used to work as a fruit wholesale driver, he would go on trips to Veracruz and only rest for one day, and he woul with her, and we have been living all together like this for about seven years. [… ] The store belongs to one of my uncles, my maternal uncles live in the United States, my mom proposed my uncle buying a place and put a store there, that they could buy it Ixmiquilpan, and that she could manage it all. […] My uncle bought the transfer of the place and my mother manages the store. My uncle said, “well, buy it and just remember to keep sending me money.” My mom sends him money from time to time, they put it in an account otherwise, or they give it to my grandparents. In Ixmiquilpan most people get resources from the United States; well, it is all crowded in market days, because people receive their remittances, as all High Schools are close by, both private and federal, and elementary schools too, we are in a central area, all students come over [and buy in the business] [… ] (Paula, personal communication, September 12, 2019).

This testimony exposes an indirect way in which remittances favor the education of some young university students through investment in a microenterprise. The prosperity of the business is associated with the commercial dynamics in the region since in the Mezquital Valley the “economic, political and social center is the city of Ixmiquilpan” (Rivera, 2006, p. 253). Likewise, since the eighties of the 20th century, Ixmiquilpan has been characterized as an area of great expulsion of migrants to the United States, who then work as labor hands in the states of Georgia, Florida, North, and South Carolina (Rivera, 2006). Due to the above, this family’s business benefits from the dynamics generated by remittances in the municipality, since money flows allow for the purchasing and selling of products and services. These conditions, in turn, motivated the young woman’s family to emigrate to that municipality, a fact consistent with what Munster (2014) found regarding the dynamics of investing remittances in regions where there is a more developed economy, not always corresponding to the area of origin of those who receive said remittances.

Therefore, the decision to transfer the business to Ixmiquilpan was likely a key element for the brother to invest. Other determining factors for the success of the enterprise was the prior knowledge that the student’s mother had about the production and administration of the business line, as well as the fact that she managed to generate profit and create jobs, which is not a common result of remittances, since women who undertake businesses with remittances tend not to be as successful. In the words of Munster (2014), women open businesses that do not survive in the long term because they are driven by the logic of survival instead of the logic of accumulation.

The mother of this participant directs the aforementioned strategies, which results in a greater return on the investment, an economic undertaking that over the years has become a determining factor in the economic autonomy of the family, favoring the enrollment and permanence of the young woman in the university, and impacting her economic agency.

Remittances as a Support Network Upon the Unexpected Lack of Provision from the Father

Giorguli and Serratos (2009) identified that in Mexico when households have remittances and other income, the moment in which teenagers leave the school system is delayed. In the following data segment, the participant’s mother asks her brother to send remittances in response to the father’s lack of economic provisioning, a strategy that strengthens the economic agency for the young woman to stay in university at a time when she is studying the second semester of the undergraduate degree.

It’s been three or four months [that] my father stopped supporting us, [… ] it was unexpected. [… ] Well, we didn’t know that he asked for loans, loans that truth be said… have nothing to do with the family. My mom, me, and my little brother have never been like that, demanding things from him, or anything, however, he is the kind of person who likes to drink, likes to smoke, likes to hang with women. So he, because of those vices that he has, was forced to ask for those loans. So he was already knee-deep into his expenses or maybe he had to give a down payment on the loans. And then well, [he told us] “no, I don’t have any money, do whatever you can.” The bank even took his entire payroll from his account [… ].

It was something unexpected. We organized ourselves more in terms of expenses and my mother’s uncles who are in the United States, they covered the expenses; and two other aunts who are here lent us money. From my uncles in the United States, it was not a loan, they gave it to us as support, but from my aunts here it was a loan [… ] (Lucía, personal communication, October 16, 2019).

According to the National Women’s Institute (2015), in Mexico “the perception of how difficult it is to obtain money is greater for women, regardless of their age, family relationship at home, place of residence and condition as speakers of an indigenous language, than for men” (p. 7). However, according to Zavala and Kurtz (2017) “...individuals with a strong social support network may find it easier to ask for help” (p. 4).

In this testimony, we can read how the strength of the support network makes it easier for the young woman's mother to request money from her brother, support that then shapes the student’s economic autonomy. The maternal uncle sends remittances based on ties of loyalty and affection towards the extended family group, thus making the relational agency visible. On top of that, the fact that the participant and her mother lack formal jobs limits their economic autonomy as they are not eligible for credit; thus the relational agency deploys a nucleus of economic agency in face of the crisis, through which the young woman can stay in university.

Remittances as a Support Network Needed due to Sporadic Provision from the Father

In the following testimony, the father is an economic figure only present partially, and the economic support network manifests by means of remittances received a few times a year. The participant and one of her siblings attend university, the mother is the only provider in the home, even covering the expenses of her grandchildren occasionally when another of her daughters has no income due to not having a stable job.

[Since I was born, I’ve been supported financially] mainly by my mom, I think 95%. When my parents were together, well, what they have told us is that my mom earned her money and my father his, and you could say that at that time my parents did pay for our expenses, mine, and my brothers’. But then my parents separated when I was three, so I live only with my mom ever since I was three, and she has been the one who pays for everything […]. My dad, you can say he is not very supportive. When my mom says “no, I don’t have money right now,” that’s when I say “well, I have to call dad now.” I mean, my dad never says no, he just says “well, I don't have any right now, but I will give you money as soon as I have some.”

I have uncles who are living in the United States, and they told [my mother] “well, I don’t know, I’m sending you so much [money].” But it is not like always, it has been very sporadically, I think that has happened only about five times [since I was a child] (Sara, personal communication, September 17, 2019).

The mother of this young woman is the head of the household and provides financially for the family group. The population of mothers who are head of the household in Mexico has increased in recent years; in 2014 it was 27.2% and in 2017 it was 28.5% (Forbes Staff, 2018). Also, female headship is predominant in extended households; the national average of households headed by women is 28.5%, the state of Hidalgo has a percentage above the average with 29.4% and ranking 11th among the states with the highest number of these types of households (National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), 2017).

Apparently, the divorce of her parents and the limited provisioning from the father of this young woman resulted in mechanisms of relational agency as a response of support from the uncles through remittances, in such a way that remittances have become an element of economic autonomy for her and her mother, and even if this autonomy is provisional, it still benefits a space of economic agency so that the participant does not abandon her studies.

Remittances As A Support Network Upon Unexpected Expenses At Home

In Mexico, spending on health care represents between 2 and 3% of the allocation of money in households. To this should be added that the state of Hidalgo is among the six with the lowest average household income (National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), 2018). Under such circumstances, an unforeseen expense in health represents a serious difficulty in the family economy.

I have an uncle [my mom’s brother] who is also in the United States, and yes, he is a very good person, and when we have found ourselves in circumstances where we can't make ends meet, well my uncle has supported us with that. He doesn’t give it to me directly, but I feel like he supports me, because, well he helps my mom, helps my family, and well, that benefits me since I was a child, [since I was] about ten, twelve years, because it was around that age that my mom divorced my father. That’s when my uncle said, “if something is needed or you need something, or you see yourself in a situation that you can’t afford, whatever it is, then tell me and I’ll give you money.” I think it is since back then that my uncle helps us, but he doesn't send us money every eight days. For example, right now that my brother had an accident, well my uncle told him “do you need money? I’m sending you money.” And he already sent him a little bit, and well, it basically is in case of an emergency that my mother tells him “I don’t have anywhere to go now, I'm not gonna make it,” and that’s when my uncle says “well, I’ll help you” (Carmen, personal communication, October 8, 2019).

The emergency remittances sent by the uncle of the interviewee are an element of protection for her and her mother since they serve as an economic contingency and survival strategy. Her precariousness leads her to use remittances as a way to have an economic agency that makes it possible for her to stay in university.

The sense of community that governs relationships between people is quite noticeable in the Mezquital Valley, this impacting in a certain way the access to higher education for these women. Maternal uncles may send remittances in response to what Burkitt (2015) calls the emotional dimension of agency, yet we still wonder if these men do so with the expectation that their sisters (or even the nieces) will eventually reciprocate through caring for them when they are older.

Finally, remittances allow for young women to establish links with the university educational system, which relates to a gender element since by their mothers’ practicing sorority, by making use of the economic resources they receive through remittances for the benefit of their daughters, these mothers enable the creation of a support network that potentializes the economic autonomy of the students and the exercise of their economic rights.

Closing remarks

This study contributes to the knowledge about one of the effects of remittances in the households of the Mezquital Valley, Hidalgo, Mexico. It accounts for economic networks configured through the family bond between migrant men in the United States and their birth sisters, residents in the region of origin.

The mothers of these students established alliances with their migrant brothers and built a support network to improve the family economy or pay for unexpected expenses; or, to face contingencies due to the lack of provisioning of their children's father, for example, after a divorce, or temporarily due to addictive behaviors that prevent the father from providing for his family. Consequently, the characteristics of these remittances serve an auxiliary function in the economy of the women of the Mezquital Valley and their resonance in the permanence of their daughters in university.

In addition, the fact that mothers decide to manage the money so that young women can access university education is an action that in gender theory is called sorority motherhood. In other words, it is about the solitary support of mothers towards their daughters. Marcela Lagarde y de los Ríos (2006) states that sorority arises from the alliance between women as a result of the positive identification between them; it is the support that allows them to access fairer living conditions. In accordance with the above, the results of this work show the gender impact resulting from remittances.

Likewise, the autonomy of women demands that they “be able to choose, agree or ignore cultural prescriptions” (Howard-Hassmann, 2011, p. 435). In this case, young women and their mothers, by not following the socially expected norm about staying at the lowest educational level for women in the region, achieve a certain economic autonomy through sorority. Mothers, through the economic agency granted to them by remittances, deliberately use this income to promote the education of young women. Thus, upon the occurrence of restrictive economic situations, the support networks empower the participants to exercise their economic agency and remain in university by means of international remittances, thus benefiting the economic rights as well as the access to higher education of young women.

Having a support grant —all participants are beneficiaries of a government program called Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro (Youth Writing the Future), which consists of a scholarship support through which beneficiaries receive 2,400 MXN per month (116.69 USD) (National Coordination of Scholarships for Wellness, Benito Juárez, 2019)— enables young women to cushion economic needs and continue their studies, an element that when combined with remittances, enables a certain level of economic autonomy among these university students of the Mezquital Valley.

It should be clarified that migrant uncles provide remittances to the extended family in order to create savings allowing for economic investment, although such is not common in Mexico, where remittances are generally used for current household spending, that is to say, for survival (Franco, 2001). Thus, the cases presented in this paper show the advantageous position of these students compared to the common destination of remittances in Mexico. In addition, the results match the findings by Kandel and Massey (2002) regarding the effects of remittances: they cannot be generalized since they depend on the community under study. This research shows that a qualitative analysis through a gender perspective approach can provide accurate data on the impact of remittances in particular contexts.

On the one hand, the phenomenon of massive international migration to the United States taking place between 1995 and 2000 in the Mezquital Valley, and on the other, the establishing of the Actopan High School of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo in the year 2000 (located in this region), are likely the situation that 20 years later has allowed us to record one of the economic strategies that, based on remittances, contributes to the economic agency, access, and permanence of women in higher education in this area of the country. It will be necessary to inquire whether other areas with a rooted tradition of migration towards the United States present the same phenomenon. Future studies are proposed where remittances can be weighted as a hypothesis in the unequal collateral line kinship link, represented by young women in Mexican extended families. Likewise, investigating whether the effects of sorority and agency on the exercise of economic rights and the education of women are particular to the context analyzed or if they are replicated in other communities.

Translation: Fernando Llanas

REFERENCES

Acosta, P., Fajnzylber, P. y López, H. (2007). The Impact of Remittances on Poverty and Human Capital: Evidence from Latin American Household Surveys. World Banck Policy Research Working Paper, (4247), 1-36. Recuperado de https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/7392 [ Links ]

Acosta, R. E. y Caamal-Olvera, C. (2017). Las remesas y la permanencia escolar en México. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(33), 85-111. https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v9i33.1333 [ Links ]

Airola, J. (2007). The Use of Remittance Income in Mexico. International Migration Review, 41(4), 850-859. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00111.x [ Links ]

Ameth, E. (1 de agosto de 2019). Hidalgo es sexta entidad con ingreso más pobre: Inegi. EA NOTICIAS. Recuperado de https://emmanuelameth.com.mx/hidalgo-es-sexta-entidad-con-ingreso-mas-pobre-inegi-e3TQ3e3jY0NQ.html [ Links ]

Banco de México. (s.f). Ingresos por Remesas. Distribución por Entidad Federativa [Cuadro]. Recuperado de https://www.banxico.org.mx/SieInternet/consultarDirectorioInternetAction.do?accion=con sultarCuadroAnalitico&idCuadro=CA79§or=1&locale=es [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (8 de abril de 2019). Record High Remittances Sent Globally in 2018 [Comunicado de prensa] Recuperado de https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press- release/2019/04/08/record-high-remittances-sent-globally-in-2018 [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2002). Análisis de contenido. Madrid: Akal. [ Links ]

Bonilla, S. (2016). Las madres son las principales receptoras de remesas en la República Dominicana. Notas de Remesas, (1), 1-2. Recuperado de https://www.cemla.org/foroderemesas/notas/2016-03-notasderemesas-01.pdf [ Links ]

Burkitt, I. (2015). Relational agency: Relational sociology, agency and interaction. European Journal of Social Theory, 19(3), 322-339. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431015591426 [ Links ]

Canales, A. I. y Montiel, I. (2004). Remesas e inversión productiva en comunidades de alta migración a Estados Unidos. El caso de Teocaltiche, Jalisco. Migraciones Internacionales, 2(6), 142-172. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-89062004000100006 [ Links ]

Código Civil Federal. (2020). artículo 156, fracción III. Diario Oficial de la Federación, Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión. Última reforma 11 de enero de 2021. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/2_110121.pdf [ Links ]

Coordinación Nacional de Becas para el Bienestar Benito Juárez. (1 de enero de 2019). Beca Jóvenes Escribiendo el Futuro de Educación Superior [entrada de blog]. Recuperado de http://www.gob.mx/becasbenitojuarez/articulos/beca-jovenes-escribiendo-el-futuro-de- educacion-superior [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos México (CNDH). (s. f.). Derechos Económicos, Sociales, Culturales y Ambientales. Recuperado de https://www.cndh.org.mx/programa/39/derechos-economicos-sociales-culturales-y- ambientales [ Links ]

Concejalía de Feminismo y Diversidad Fuenlabrada. [Concejelía de Feminismo y Diversidad Fuenlabrada]. (21 de abril de 2013). Conferencia de Marcela Lagarde y de los Ríos sobre “la sororidad” [archivo de video]. Recuperado de https://youtu.be/8CKCCy6R2_g [ Links ]

Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. (2019). Artículo Tercero Constitucional, reformado. [ Links ]

Corona, M. Á. (2007). La economía de Tlapanalá. Migraciones internacionales, 4(13), 93-120. Recuperado de https://migracionesinternacionales.colef.mx/index.php/migracionesinternacionales/article/ view/1168 [ Links ]

Cruz, J. A. (2019). Fundamentos filosóficos de los derechos económicos. En J. Cruz, P. Rodríguez y P. Larrañaga, Derechos económicos: Una aproximación conceptual, (pp. 11- 88). Naciones Unidas, CEPAL, CNDH. Recuperado de https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/44846-derechos-economicos-aproximacion- conceptual [ Links ]

Deere, C. D., Alvarado, G., Oduro, A. D. y Boakye-Yiadom, L. (2015). Gender, remittances and asset accumulation in Ecuador and Ghana. Recuperado de https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/6/gender-remittances-and- asset-accumulation [ Links ]

Durand, J. (2016). Historia mínima de la migración México Estados Unidos. Ciudad de México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Escala, L. (2006). La dimensión organizativa de la migración hidalguense en los Estados Unidos. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. [ Links ]

Forbes Staff. (28 de mayo de 2018). Aumentan los hogares con jefas de familia en México: INEGI. Forbes México. Recuperado de https://www.forbes.com.mx/aumentan-los-hogares-con-jefas-de-familia-en-mexico-inegi/ [ Links ]

Franco, L. M. (2001). El efecto de las remesas en la ciudad de Ixmiquilpan, 1990-2007 (tesis doctoral en Urbanismo). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. [ Links ]

García, Y. y Cuecuecha, A. (2020). El impacto de las remesas internacionales sobre la inversión en educación en la localidad de Caltimacán, Hidalgo. Migraciones Internacionales, 11, 1- 26. https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.1590 [ Links ]

Giorguli, S. E. y Serratos, I. (2009). El impacto de la migración internacional sobre la asistencia escolar en México: ¿paradojas de migración? En P. Leite y S. Giorguli (Coords.), El estado de la migración. Las políticas públicas ante los retos de la migración mexicana a Estados Unidos, (pp. 313-344). Recuperado de http://conapo.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/migracion_internacional/politicaspublicas/ COMPLETO.pdf [ Links ]

Howard-Hassmann, R. E. (2011). Universal Women’s Rights Since 1970: The Centrality of Autonomy and Agency. Journal of Human Rights, 10(4), 433-449. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2011.619398 [ Links ]

Htun, M., Jensenius, F. R. y Nelson-Nuñez, J. (2019). Gender-Discriminatory Laws and Women’s Economic Agency. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 26(2), 193-222. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxy042 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (2004). La migración en Hidalgo: XII censo general de población y vivienda, 2000. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825497743 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (Inegi). (2012). Clasificación de parentescos. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/mti/2013/doc/clasificacion_parentescos.p df [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (2017). Encuesta Nacional de los Hogares 2017. ENH. Informe operativo. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825101503 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (2018). Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares (ENIGH). 2018 Nueva serie. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enigh/nc/2018/ [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres (Inmujeres). (2015). Boletín estadístico. Cómo funcionan las redes de apoyo familiar y social en México. Recuperado de http://cedoc.inmujeres.gob.mx/Pag_cat_libre.php?criterio=C%D3MO+FUNCIONAN+LA S+REDES+DE+APOYO+FAMILIAR+Y+SOCIAL+EN+M%C9XICO&search=Buscar [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres (Inmujeres). (19 de diciembre de 2016). Los Derechos Humanos de las Mujeres [entrada de blog]. Recuperado de http://www.gob.mx/inmujeres/articulos/los-derechos-humanos-de-las-mujeres?idiom=es [ Links ]

International Organization of Migration. (2020). Derecho internacional sobre migración N°34- Glosario de la OIM sobre Migración. Recuperado de https://publications.iom.int/books/derecho-internacional-sobre-migracion-ndeg34-glosario-de-la-oim-sobre-migracion [ Links ]

Kandel, W. y Massey, D. S. (2002). The Culture of Mexican Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Social Forces, 80(3), 981-1004. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2002.0009 [ Links ]

Lagarde y de los Ríos, M. (2006). Pacto entro Mujeres Sororidad. Aportes para el debate, 25, 123-135. Recuperado de http://www.asociacionag.org.ar/pdfaportes/25/09.pdf [ Links ]

Lagarde y de los Ríos, M. (11 de junio de 2009). La política feminista de la sororidad. Mujeres en red. El periódico feminista. Recuperado de http://www.mujeresenred.net/spip.php?article1771 [ Links ]

Lagarde y de los Ríos, M. (2012). El feminismo en mi vida. Hitos, claves y utopías. Distrito Federal: Inmujeres. [ Links ]

López-Córdova, E. (2006). Globalization, Migration and Development: The Role of Mexican Migrant Remittances (Inter-American Development Bank No. 20). Buenos Aires: Inter- American Development Bank. [ Links ]

Lozares, C. (1996). La teoría de redes sociales. Papers. Revista de Sociologia, 48, 103-126. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers/v48n0.1814 [ Links ]

Massey, D. (2016). The Mexico-U.S. Border in the American Imagination. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 160(2), 160-177. Recuperado de http://insyde.org.mx/pdf/movilidad-humana/massey_douglas_s_2016_border_in_the_american_imagination.pdf [ Links ]

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L. y Brashears, M. E. (2006). Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades. American Sociological Review, 71(3), 353-375. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100301 [ Links ]

Mora, J. J. y Arellano, J. (2016). Las remesas como determinantes del gasto en las zonas rurales de México. Estudios Fronterizos, 17(33), 231-259. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2016.33.a09 [ Links ]

Munster, B. (2014). Remesas y pobreza desde una perspectiva de género. El caso del consejo popular de Santa Fe (Cuba). Buenos Aires: CLASCO. [ Links ]

Oficina del Alto Comisionado de Derechos Humanos (OACDH). (1976). Pacto Internacional de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales. Recuperado de https://www.ohchr.org/SP/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx [ Links ]

Organismo Internacional de Juventud (OIJ). (2008). Tratado Internacional de Derechos de la Juventud. Convención Iberoamericana de Derechos de los Jovenes (cidj). Recuperado de https://oij.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CIDJ-A6-ESP-VERTICAL.pdf [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU) y Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (Cepal). (2016). Autonomía de las mujeres e igualdad en la agenda de desarrollo sostenible. Recuperado de https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/40633-autonomia-mujeres-igualdad-la-agenda-desarrollo-sostenible [ Links ]

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico (OECD). (2017). Interacciones entre Políticas Públicas, Migración y Desarrollo. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276710-es [ Links ]

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico (OECD). (2019). Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en [ Links ]

Orozco, M. (2013). Migrant remittances and development in the global economy. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

Quezada, M. F. (2018). Migración internacional y desarrollo local: La experiencia de dos localidades otomíes del Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo, México. Región y sociedad, 30(73), 291-323. https://doi.org/10.22198/rys.2018.73.a975 [ Links ]

Redacción Animal Político. (12 de agosto de 2018). La realidad de la juventud en México: Pobreza, discriminación e incumplimiento de sus derechos. Animal Político. Recuperado de https://www.animalpolitico.com/2018/08/dia-de-la-juventud-pobreza-discriminacion/ [ Links ]

Rivera, M. G. (2000). La modificación de los papeles sociales de las mujeres de El Boxo, en el Estado de Hidalgo, a partir de la migración. Tesis de Licenciatura en Sociología de la Educación. Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, México, Distrito Federal. http://digitalacademico.ajusco.upn.mx:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/14341 [ Links ]

Rivera, M. G. (2006). La negociación de las relaciones de género en el Valle del Mezquital: Un acercamiento al caso de la participación comunitaria de mujeres hñahñus. Estudios de Cultura Otopame, 5, 249-266. Recuperado de http://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/eco/article/view/17054 [ Links ]

Rivera, M. G. R. y Quezada, M. F. Q. (2011). El Valle del Mezquital, estado de Hidalgo. Itinerario, balances y paradojas de la migración internacional de una región de México hacia Estados Unidos. Revista Trace, (60), 85-101. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.22134/trace.60.2011.450 [ Links ]

Sawyer, A. (2015). Migración, remesas y escolarización: ¿estímulos o amenazas para la Educación para Todos en México? Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Comparada, 6(8), 76-90. Recuperado de http://www.saece.com.ar/relec/revistas/8/mon3.pdf [ Links ]

Secretaría de Asustos Jurídicos. (7 al 22 de noviembre 1978). Convención Americana sobre Derechos Humanos [conferencia]. En Conferencia Especializada Interamericana sobre Derechos Humanos (B-32). San José, Costa Rica: Organización de los Estados Americanos Recuperado de https://www.oas.org/dil/esp/tratados_b- 32_convencion_americana_sobre_derechos_humanos.htm [ Links ]

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP). (2019). Principales Cifras del Sistema Educativo Nacional 2018-2019. Recuperado de https://www.planeacion.sep.gob.mx/Doc/estadistica_e_indicadores/principales_cifras/prin cipales_cifras_2018_2019_bolsillo.pdf [ Links ]

Solís, M. y Fortuny, P. (2010). Otomíes hidalguenses y mayas yucatecos. Nuevas caras de la migración indígena y viejas formas de organización. Migraciones Internacionales, 5(19), 101-138. https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v5i19.1072 [ Links ]

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo (UAEH). (2020). Tercer Informe de la Administración Universitaria: Anuario Estadístico 2019. Recuperado de https://www.uaeh.edu.mx/informe/2017-2023/3/anuario.html [ Links ]

Valadez, B. (23 de agosto de 2018). Solo 21 de 100 alumnos terminan la universidad. Milenio. Recuperado de https://www.milenio.com/negocios/solo-21-de-100-alumnos-terminan-la- universidad [ Links ]

Zavala, E. y Kurtz, D. L. (2017). Applying Differential Coercion and Social Support Theory to Intimate Partner Violence: Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, 1-2. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517731314 [ Links ]

2 Here, legal address is understood as the one they share with their relatives, since several young people live in Actopan from Monday to Friday and usually rent rooms where they stay for approximately 1,400 MXN per month; other young women travel daily to the university center from the communities or places where they live.

Received: July 07, 2020; Accepted: November 19, 2020

texto em

texto em