Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Migraciones internacionales

versão On-line ISSN 2594-0279versão impressa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.11 Tijuana 2020 Epub 02-Out-2020

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.1742

Article

Strategies of Haitian Migrant Families for Their Children in Face of the Dominican Republic’s Anti-Immigrant Policies

1El Colegio de México, México, scmerone@colmex.mx

2Becario IIJ-UNAM, México, eduardotorrephd@gmail.com

The migration policies of the Dominican Republic (DR in the hereafter) have restricted the access to Dominican citizenship for thousands of Haitian children brought to this country during childhood, as well as for minors born in the DR from Haitian parents; that is Dominico-Haitian children. However, parents have not passively accepted this situation. The goal of this paper is to analyze two strategies of Haitian parents living in the DR for their children, set to minimize the negative effects of anti-immigrant policies: 1) obtaining official DR citizenship documents for their children, and 2) ensuring the attendance of children to both Dominican and Haitian schools. Also, the current situation of Haitian- origin populations in the DR is set into historical and political context here.

Keywords: immigration policies; strategies of migrant families; policies for access to nationality; Haiti; Dominican Republic

Las políticas migratorias de República Dominicana (RD) han restringido el acceso a la nacionalidad dominicana de miles de menores haitianos llevados a este país durante la infancia, así como a menores nacidos en RD de padres haitianos, es decir, menores dominico-haitianos; sin embargo, sus padres no se han mantenido pasivos frente a esta situación. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar dos estrategias de las familias haitianas en RD para sus hijos menores que tienen como fin minimizar los efectos negativos de esas políticas antiinmigrantes: 1) la obtención de documentos oficiales de RD para los hijos, y 2) su asistencia tanto a escuelas dominicanas como a haitianas. Adicionalmente, se contextualiza histórica y políticamente la situación actual de la población de origen haitiano en RD.

Palabras clave: políticas migratorias; estrategias familiares; nacionalidad; Haití; República Dominicana

INTRODUCTION

For decades now, the restrictive rules imposed by the Dominican Republic (DR in the hereafter) on foreigners in terms of obtaining citizenship have created a situation of uncertainty for thousands of DR-born children of Haitian parents3 and Haitian children brought to this country in their childhood.4 Most of them, children of undocumented Haitian immigrants, have been prevented from obtaining Dominican citizenship. On the one hand, Dominico-Haitians cannot obtain nationality despite having been born within Dominican territory and the existence of the ius soli principle in the Dominican legal system (Cedeño, 1992; Perdomo Cordero, 2016); on the other, most Haitians brought to the DR during their childhood, same as their parents, have no legal means to regularize their situation in this country. The different measures taken over the years by the Central Electoral Board (Junta Central Electoral) to hinder or outright prevent the obtainment of Dominican nationality for children were particularly effective in September 2013 when the Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional) ruled the denial of citizenship to any person born in the country from undocumented immigrant parents. The laws implemented to address this situation did not achieve the desired results. Therefore, children in the described situation are and possibly will remain subject to deportation proceedings; they are also likely to experience poor working conditions and social exclusion, despite having lived in the Dominican Republic their whole lives or for the most part.

In face of this uncertain and threatening state of affairs, many families of Haitian origin in the Dominican Republic have undertaken an active role in developing strategies to minimize the harmful effects of anti-immigrant policies on the lives of their children, whether they are born in that country or not. As a matter of fact, this population has developed a wide range of strategies and practices aimed at reducing the impact of the multiple difficulties faced by its members (Méroné, 2017). The aim of this article is to analyze two of the strategies of families for their children: 1) Obtaining official Dominican Republic documents for them and 2) Making sure they attend both Dominican and Haitian schools. Both strategies are linked to anticipating or preventing –or at least ameliorating– those adverse situations derived from Dominican anti-immigrant policies.

The article is divided into four sections. In the first, the current migration from Haiti to the Dominican Republic is historically contextualized. In the second, Dominican anti- immigrant policies and their negative effects on the Haitian population residing in that country are analyzed from a historical perspective –with special attention given to those recently enacted regarding the children of undocumented Haitian immigrants–; as well as certain theoretical-conceptual aspects relevant to the analysis of family strategies in response to such policies. In the third section, some demographic characteristics of Haitian immigrants (including Haitian children brought to the country in their childhood) and Dominico-Haitians are analyzed, as well as the family homes to which they belong, with the purpose of highlighting the importance of strategies for children in this context. In the fourth, based on seven interviews selected from among the 53 conducted with members of Haitian immigrant families residing in the DR, we analyze the strategies linked to the migration policies that parents deploy for their children.

CURRENT HAITIAN MIGRATION TO THE DR FROM A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Although there is a long history of movements of people from Haiti to the DR (Michel, 2005; Moral, 1978; Del Castillo, 1978), there is an almost general consensus among scholars to date the beginning of Haitian migration to this country at the beginning of the 20th century. In fact, between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the investment of American capital in the region initiated a project to transform the Caribbean sugar industry and take advantage of a series of international5 and local6 circumstances; for different reasons, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Puerto Rico were the main beneficiaries of these investments (Castor, 1983; Domenach, 1986).

Due to a series of structural and short-term barriers7 that prevailed in Haiti at that time (Martínez, 1999; Castor, 1971), this country was not included in the new regional economy as a site for facilities of that industry, but only as a provider of workforce.8 At that time, for different reasons, the Dominican Republic lacked sufficient workers to carry out all the work generated by the development of the sugar sector (Tejada Yangüela, 2001; Del Castillo, 1978).9

Another factor that prompted the beginning of an intense Haitian migration to the Dominican Republic was the simultaneous military occupation of both countries by the United States (U.S.) (Haiti from 1915 to 1934, DR from 1916 to 1924). In Haiti, one of the corollaries of the occupation was the large-scale establishment of American agricultural enterprises, causing thousands of peasants to be stripped of the land they occupied (Moral, 1978; Castor, 1971; Gaillard, 1981). Such policies, along with other measures to the detriment of the peasantry, led to the creation of a rural guerrilla against the occupier, which, in order to get rid of the riots and the surplus of agricultural workers, promoted the departure of Haitian peasants to the sugar mills in Dominican Republic and Cuba (Castor, 1983). This again benefited the financial and business interests of the U.S., who at the time controlled much of the sugar production in those countries.

It is clear that the vigorous Haitian migration to the DR arose within the framework of a project not conceived by the Haitian and Dominican states and societies. On the contrary, this phenomenon would, in the beginning, generate great concern in several DR and Haitian population sectors (Méroné, 2017). However, the migration of Haitian workers to the DR continued to increase, so that in the 1920s this workforce managed to dominate the Dominican sugar labor market, displacing workers from the other islands (Del Castillo, 1978). From then and until now, the relationship between the Haitian migration to the DR and the sugar industry of this country has become so close that much of the history of this migration is mixed with that of that industry, because during most of the 20th century, its dynamics would determine the numbers of Haitian workers who would migrate to the DR (Lozano, 2005).

The growth of migration took place parallel to the dispute on the delimitation of the border between the two countries, which was finally resolved in 1936. Precisely, the establishing of the border would be, according to several authors, one of the main causes of the arguably most extreme cruelty suffered by the population of Haitian origin in the DR: the killing of thousands of its members in 1937 (Turits, 2014; Moya Pons, 1992; Castor, 1983; Price-Mars, 1953). According to these authors, the dividing line between the two countries left several communities of Haitians within Dominican territory, so that a large portion of the Dominican border region remained as a “culturally Haitian” strip.

This situation was perceived in some sectors as a danger to Dominican national sovereignty and identity (Castor, 1983). According to several authors, dictator Rafael Trujillo implemented the so-called Dominicanization plan on the Dominican border area in response to this “danger”; this plan aimed at eliminating Haitian communities and replacing them with Dominicans and white immigrants from other countries, with the purpose of building a demographic and cultural “wall” against Haitian immigration (Moya Pons, 1992; Castor, 1983).

Nonetheless, and despite the massacre of 1937, the Dominican sugar industry could not do without Haitian labor; and so, sugar cane plantation areas were not affected by these atrocities. To ensure enough workforce, in 1952, Trujillo signed an agreement with the Haitian government to hire Haitian temporary workers for that sector; they had become the engine of the Dominican economy. That agreement between the two governments was renewed every five years and remained in force until 1986 since from the mid-1970s the sugar industry weakened; after that and from the point of view of government leaders, it was no longer useful to continue with the agreement (Lozano, 2005, 1998).

In addition to the emerging sugar industry crisis, several changes also occurred in the two countries that affected the volume, composition of the flow, and the economic sectors in which migrants were inserted. In the DR, the agrarian crisis affected not only sugar production but agriculture in the country as a whole, aggravating the living standards of rural producers, who then migrated in significant volumes to the cities or the U.S. (Lozano, 2005, 1998). This situation caused a shortage of native labor in crops such as coffee, rice, and tobacco, favoring the entry of Haitian workers (Lozano, 2005). Subsequently, these workers entered into other production fields, such as bananas, pineapples or tomatoes (Báez Evertsz & Lozano, 1985).

On the other hand, the changes that took place in the agricultural sector occurred in a context of broader economic diversification. In the 1970s, the outsourcing process of the Dominican economy began with the development of sectors such as free zones for export, industrial activities, and services (Ariza, 2004; Tejada Yangüela, 2001). Although Haitians did not insert in these precise sectors in great numbers, the new economic dynamics did attract larger volumes of immigrants of different profiles. In fact, the changes that occurred in migration at that time made some authors talk about a new Haitian migration to the DR (Silié, Segura, & Dore Cabral, 2002).

At the same period, various events in Haiti worsened the economic, political, social and environmental situation, increasing the number of potential migrants. For example, between the late 1970s and early 1980s, because of the swine fever, the government decided to kill large pig populations, which represented the economic backup in rural areas, accentuating poverty in those areas. In 1986, the fall of Jean-Claude Duvalier and the Dechoukaj10 movement that followed worsened the economic situation. On the other hand, between 1991 and 1994, the trade embargo imposed by different international organizations against Haiti greatly affected the country’s economy, destroying thousands of jobs, especially in the textile manufacturing sector.

Finally, the series of political crises and natural disasters that occurred between 1990 and 2000, which culminated in the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the cholera outbreak and the subsequent hurricanes and floods, caused a generalized desire to migrate in a large part of the population. Some of them ended up in the DR, a place with new opportunities to improve their lives, or an ideal route to reach other countries.

To sum all this up, although in Haiti there have been factors encouraging large portions of its citizens to migrate to the DR, the migration flow also responds to factors of attraction in the latter, which have changed over the decades. However, despite the role that Haitian immigrants have played in the Dominican sugar industry and other economic sectors, in the DR there is a reinstated rejection towards those Haitians who want to integrate into the different spheres of society. This rejection is manifested when they try to obtain Dominican nationality, and it affects their children regardless of whether they are born in the Dominican territory or were brought to this country in their childhood.

DOMINICAN RESTRICTIVE IMMIGRATION POLICIES, THEIR EFFECTS ON THE LIVES OF HAITIAN-DESCENT CHILDREN, AND FAMILY STRATEGIES

On February 27th, 1844, the DR emerged as an independent nation when it separated from Haiti,11 but with a substantial demographic deficit against the neighboring country. Since then, the concern arose among the Dominican to populate an almost empty territory; first, to defend against the whims and successive attempts of Haitian authorities of the time to recover the eastern part of the island (Escolano Giménez, 2010); and second, out of a desire to “reconquer” territories that, having belonged to the former Spanish colony, became part of Haiti during the events that led to the political independence of this country in 1804 (Moya Pons, 1992). Therefore, Dominican political elites purposefully promoted the arrival of European immigrants from former Spanish colonies to develop the country (Escolano Giménez, 2010; Capdevila, 2004) and, being sufficiently different from the Haitians in “racial” and cultural terms, to prevent any eventual reunification between the two countries (Lilón, 2010).

In this sense, Dominican policies and laws regarding the immigrant population in their territory have been, throughout their history, restrictive and discriminatory towards Haitians and their descendants (Capdevila, 2004; Cedeño, 1992; Perdomo Cordero, 2016). However, and addressing the needs of the labor market, these policies have also been highly permissive in certain sectors in order to obtain a migrant workforce, both regular and irregular, that is cheap, docile and exploitable.

According to Capdevila (2004) and Martínez (1999), the first migration laws of the late 19th and early 20th centuries provided incentives that favored the arrival and settlement of Caucasian Europeans, at the same time instituting a series of dynamics aimed at the exclusion of “blacks” from the neighboring country and other Caribbean islands (Capdevila, 2004). That is, the legal framework for migration was aimed at opposing “a barrier of white, healthy and hardworking people to the gradual invasion of Haitians” (Peynado, 1909, p. 5, cited by Capdevila, 2004, p. 442).

Although the laws following thereafter gradually eliminated the advantages granted to Caucasians, they did not stop excluding Haitians and their children, born in or brought to the DR. As an example, although the migration laws of 1932 and 1939 allowed temporary workers to attend to the low-skilled tasks of the sugar industry –essentially Haitians– they were placed under an exception regime that prevented them from reaching autonomy or remaining on a regular basis in the Dominican territory if they wished so (Capdevila, 2004). Since 1952, the consecutive bilateral agreements for the hiring of Haitian labor introduced the repatriation of Haitian workers at the end of the harvest season; at the same time, they regulated their settlement in specific places of the territory –the bateyes, outbuildings around and neighboring sugar mills–denying them any legal existence outside of them (Lozano, 2005; Moya Pons, 1986).

It is in this tradition that the policies against the Dominico-Haitians adopted in recent decades are inscribed. These policies include measures that have denied Dominican nationality to thousands of Haitian people born in the DR; they have also taken the Dominican nationality from thousands of people who until recent times had been considered as legal citizens.

In order to understand the current legal situation of a large portion of Dominico- Haitians, it is necessary to look back at its legal precedents dating back at least to the Constitution of 1907. In that constitutional text, the transitoriality exception was included for the obtainment of nationality according to the principle of ius soli. This constitutional provision results in that many times Haitian parents in an irregular legal situation are considered as people in transit, and so their children are denied nationality (Cedeño, 1992). This interpretation by the authorities has resulted in various legislative changes, several administrative circulars and long legal battles before Dominican and international jurisdictions.

A first attempt to grant de iure value to the exclusion, which was de facto being carried out against the Haitians and their descendants –particularly related to the obtainment of nationality by Dominico-Haitians– was the general migration law of 2004 (Law No. 285- 04, General of Migration, El Congreso Nacional, 2004). This legal document includes in its article 36, paragraphs 5, 6 and 9 that “temporary workers,” “foreigners residing in areas bordering the national territory” and “students who arrive in the country to study as regular students in officially recognized establishments” –all of whom are mostly Haitians– are considered to be “non-residents.” In paragraph 10 of the same article, the law states that “non-residents are considered persons in transit” (Law No. 285-04, General of Migration, art. 36, El Congreso Nacional, 2004).

As Lozano (2005, p. 89) points out, it is a “legal device to exclude temporary workers from the rights and legal conditions that may benefit them […], but, above all, it is an artifice to manipulate […] the issue of the nationality of the children of foreigners born in the country, mainly of Haitian parents.” As a matter of fact, and contrary to the principle of normative hierarchy, the migration law of 2004 restricts the constitutional law of ius soli in the attribution of nationality to the children of “non-residents”; a provision that would be confirmed in the 2010 constitutional review. Indeed, in its article 18, paragraph 3, the new Dominican Magna Carta validates the exception of land rights to children of “foreigners who are in transit or reside illegally in Dominican territory,” adding that “all foreigners defined as such according to Dominican law are considered persons in transit” (The National Council of Reforms, 2010, art. 18).

After the 2004 law, Dominico-Haitians began to face greater difficulties in obtaining identity and voting cards,12 since the Central Electoral Board (JCE, Junta Central Electoral), applying the law retroactively, rejected their requests arguing that their parents were “non-residents” or “people in transit” at the time of their birth.13 Therefore, they should never have had the right to Dominican nationality in the first place (Open Society Foundations, 2010). Following this, a circular enforced in 2007 by the JCE urged civil registry officials to “refrain from issuing copies of birth certificates of children with foreign parents, if there is no proof that said parents have legal residence or status in the Dominican Republic” (Administrative Chamber of the JCE, 2007).14

On September 23, 2013, the Dominican Constitutional Tribunal (TC) abruptly “closed” the debate on the nationality of Dominico-Haitians with a ruling that reignited the discord between the two countries and even harmed DR’s relations with other countries and regional institutions. Ruling TC/0168/13 meant that tens of thousands of people, mostly of Haitian descent, born in the DR from June 1929 to January 2010, now lacked the Dominican citizenship they had enjoyed all their lives.

Following this ruling, a wave of controversy and severe criticism arose nationally and internationally, leading the Dominican government to enforce the National Regularization Plan for Foreigners in Conditions of Illegal Migration in the Dominican Republic (PNRE), and Law 169-14. Both initiatives aimed at regularizing people under illegal situations in the country and allowing a part of those affected by the aforementioned ruling access to citizenship. However, both these instruments have provided limited results, and so the legal limbo of Dominico-Haitians and Haitian immigrants remains.

If they stay in the DR, whether Haitian children brought in their childhood or Dominico-Haitians, their irregular legal status can position them in conditions of precarious employment and social exclusion similar to those of their Haitian ascendants. Now, if they instead return to Haiti voluntarily or through a deportation process (theirs or of a family member), they may face problems of various kinds to integrate, as chances are they do not even know this country at all, regardless of their place of birth. Depending on the age at which mobility from Haiti occurs, they may face various problems and difficulties in adapting to the Haitian school system, validating their DR studies, or those derived from not knowing the languages spoken in Haiti (Creole and French), from their insertion in the Haitian labor market, or even in finding a place to live and obtaining sufficient income for its maintenance.

As mentioned before, Haitian immigrant families have developed a series of strategies in order to make their children less likely to face adverse future scenarios, such as the lack of opportunities, and deportation. Therefore, before analyzing the aforementioned strategies, it would be appropriate to review the contributions made by different works in the field of strategies of migrants and their families.

Migrants and their families, particularly so when they lack legal documentation, have to deal with the migration policies that the receiving states –immigration policies, that is– and those states through which they transit –transit policies– approve to their prejudice. Also, recent research has shown that migrant families can develop strategies to avoid the negative effects of anti-immigrant policies and economic crises (Pedone, Echeverri, & Gil Araujo, 2014; Bean, Brown, & Bachmeier, 2015; Torre Cantalapiedra & Anguiano Téllez, 2016; Vargas Valle & Coubès, 2017).

For example, Pedone et al. (2014) have analyzed how Colombian and Ecuadorian families, in a period of economic crisis in Spain and against this country’s policies on illegal immigrants, rearrange the place of residence of their members as a strategy to ameliorate the adverse effects promoted by the political and economic context they find themselves in. Vargas Valle and Coubès (2017) examine the growth in births of Mexican- descent children in the U.S. as a cross-border life strategy to ensure that these children will eventually gain access to the U.S. labor market. Unlike what happens in our present case study, anyone born in the U.S. acquires U.S. citizenship by way of ius soli, regardless of the immigration status of their parents.

In addition to these strategies, another relevant theoretical-conceptual aspect in our work is familism. The available literature indicates that families in Latin America and the Caribbean are characterized by establishing strong ties among their members. This means that when children are young, parents make decisions about the future of the family prioritizing their welfare. In this sense, Puyana Villamizar (2008) refers to familism as the tendency of families and, especially, mothers, to concentrate all their functions in the raising and care of children and the elderly.

These works show that families do hold certain capacity for agency, manifested in their strategies, to face the difficulties imposed by the context of restrictive and persecutory policies as they establish themselves as mediating spaces between social structures and the individuals who make them up. This function is particularly important during the upbringing of children since they are in a situation of dependence and vulnerability. In this work, we follow this incipient line of research, focusing on the strategies of Haitian families regarding their children, since Dominican anti-immigrant policies threaten to harm the development of their lives, particularly in terms of the possibility of remaining in the DR and developing their professional careers.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF HAITIAN FAMILIES IN THE DR

Based on data from the National Immigrant Survey conducted in 2012 by the National Statistical Office of the Dominican Republic –First National Immigrant Survey in the Dominican Republic, ENI-2012 (ONE, 2013)–, this section will analyze some of the demographic characteristics of Haitian immigrants (including Haitian children brought to the DR in their childhood), their children born in this country, as well as selected characteristics of their households. The variables to analyze these two groups, both individually and household-wise, were chosen because they allow us to understand the demographic context in which parents’ strategies for their children are developed.

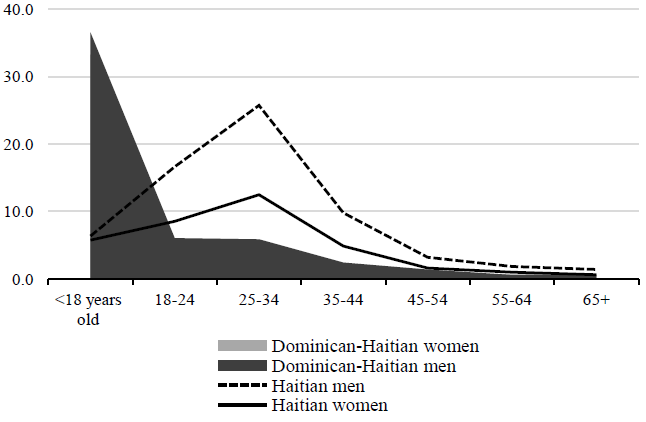

Now, Figure 1 ighlights a huge contrast between the two groups when it comes to age structure. As can be seen, Haitians are mostly located in working ages while Dominico- Haitians constitute a young group, 18 years of age or less. Undoubtedly, the concentration of Haitians in economically active ages is associated with the fact that Haitian migration to the DR has been mainly motivated by labor issues (Lozano, 2005, 1998; Survey on Haitian immigrants in the Dominican Republic, FLACSO & OIM, 2004). As we noted earlier, traditionally, Haitian migration to the DR is directed to the agricultural sector and only more recently to other market segments, diversifying the labor niches of Haitians in this country (Lozano, 2005, 1998; Silié et al., 2002).

Source: Elaborated by the authors with data from ENI-2012 (ONE, 2013).

Figure 1. Haitian and Dominico-Haitian Migrants by Sex and Large Age Groups, DR, 2012.

When it comes to the composition by sex, the information in Figure 1 shows a significant gap in favor of migrant men, especially in working ages, resulting in a very masculine group. In contrast, Dominico-Haitians have similar percentages of men and women in all age groups. Thus, according to estimates based on data from ENI-2012 (ONE, 2013), 65% of Haitian immigrants are men, while this percentage is 53.5% among Dominico-Haitians born in DR.

The insertion of Haitians into agriculture for a long period of time may partially explain the high male representation in the group since these jobs usually make use of male workforce. Also, this imbalance could be due to the social pressure exerted decades ago in Haiti against female emigration to DR, born from the belief that women who migrated to that country did so for prostitution (Méroné, 2017). However, in the last two decades, the proportion of women in the Haitian collective living in DR has shown a trend towards increase (Survey on Haitian immigrants in the Dominican Republic, FLACSO / IOM, 2004; IX National Population and Housing Census 2010, ONE, 2012). It is very likely that this trend is related to the diversity of Haitian labor niches in the DR and the reduction of social pressure against female emigration.

The recent feminization of the Haitian stock in the DR represents one of the factors that explain the rise of the Dominico-Haitian population in the latter country, and its relative overall youth as a group. For a long time, Haitian immigrants in the DR were mainly men whose spouses lived in the country of origin with their children, born mainly there. The increase in the percentage of women of working and fertile ages in the DR translates into a greater number of births with at least one parent from Haiti in the DR.

Summarizing, Figure 1 displays how, as a whole, there is a high proportion of underage children in the population of Haitian origin for whom families may perceive the need to implement actions aimed at reducing the harmful effects of restrictive policies, especially during their coming of age (18 years old),15 or in case of deportation, so that children have better educational and work opportunities either in the DR or in Haiti.

As for households, the data shows that in 2012 there were a total of 235,722 households headed by a person of Haitian origin16 in the DR, mostly of nuclear type17 (62.6%, Figure 1). Extended18 and composite19 households were less common among Haitian immigrants and Dominico-Haitians (less than 10% for each). As for sole proprietors, they were one in five households, while those made up of people without any kinship ties (non-relatives) represented only 3.8% of the population of Haitian origin in the DR. However, together, households that have more than one member in which all or some of them are related (nuclear, extended and composite households) represent 76%. This means that most of the households of Haitian or Dominico-Haitian immigrant grouped people with strong relationships (spouses, parents, children and other kinship ties). This can increase the tendency of members to develop strategies that benefit each other, such as those applied by parents to ensure a better future for their children or, at least, to cushion the adverse effects of the social environment in their lives.

Regarding the presence of persons under 18 years of age, the survey data shows that almost half of the homes of Haitian immigrants or Dominico-Haitians had at least one person with this characteristic in 2012. That is, a considerable portion of Haitian families in the DR are in a position to carry out actions that benefit their members for whom it is still possible to avoid or mitigate the negative effects of restrictive immigration policies, such as children. Also, as discussed in the previous section, most children were born in the DR (Figure 1), which can reinforce the determination of many of these families to seek the Dominican nationality for them.

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of Haitian Households in the DR, 2012.

| Household characteristics | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Household type | ||

| Sole proprietors | 47 493 | 20.1 |

| Nuclear | 147 531 | 62.6 |

| Extended | 17 021 | 7.2 |

| Composite | 14 710 | 6.2 |

| Nonrelatives | 8 967 | 3.8 |

| Total | 235 722 | 100 |

| Presence of children under 18 years old | ||

| Households without children under 18 | 125 349 | 53.2 |

| Households with children under 18 (at least 1) | 110 373 | 46.8 |

| Total | 235 722 | 100 |

Source: Authors’ calculations with data from ENI-2012 (ONE, 2013)

This shows that both the information on the type of household and that referring to the presence of children suggest that, among other functions, Haitian households in the DR are in a position to serve as protective structures for their younger members, especially in relation to immigration policies.

FAMILY STRATEGIES FOR THE CHILDREN OF HAITIANS IN THE DR

This section is based on the information collected during a research stay in the DR conducted by one of the authors between July and October 2015. During this period, 53 people were interviewed in fourteen communities; seven were selected for this analysis. These people were intentionally chosen for using at least one of the two family strategies discussed in this work. The seven people selected were between 20 and 45 years old and five of them are women. They also had low levels of schooling and engaged in various economic activities such as retail sales, education, gardening, and taxi driving. Finally, one person interviewed was unemployed and another one was studying at the time of the interview.

It should be noted that the research stay was carried out within the framework of one of the author’s doctoral thesis, essentially dealing with the differences between Haitian immigrants, Dominicans, and Dominico-Haitians in the DR labor market (Méroné, 2017). Data was collected by means of four techniques: semi-structured interviewing, direct observation, participant observation, and informal conversation. As for the fourteen communities, they were chosen because of their location among the greatest concentration areas of the Haitian population in the DR, and because they correspond to specific local labor markets. That is, the seven interviews selected for this article are part of a larger corpus that takes into account a series of processes occurring at the social micro and meso level, but articulated within a context adverse to Haitians and Dominico-Haitians.

However, one of the strategies that families have used to prevent children from lacking legal documents is to obtain identity and citizenship documents outside the established proceedings, especially birth certificates. The methods of obtaining vary and involve various factors, including Dominican families and institutions of the Dominican State. Among our interviewees, we did find that obtaining these documents may result from 1) the purchase of birth certificates or other documents of deceased Dominican children, 2) the recording of Haitian children before the civil registry by Dominican families or by other Haitian holders of Dominican IDs (these “legal parents” act as the “true” parents of the child before the law), 3) obtaining documents from local authorities that support the issuance of the birth certificate.

The families that resort to this strategy pay considerable amounts of money to obtain the “services,” either to other Haitian or Dominican families or to local authorities. Sara, Dominico-Haitian born in Barahona (DR), for whom her parents obtained the birth certificate through one of the aforementioned means, explains:

I have no problems because the person who presented me when I was a child had a [Dominican] ID. […] Imagine the number of IDs that the Board [Electoral Central] is deleting now. Why? Because they did not have valid documentation. Fortunately, the person who presented me was a Dominican (Sara, 20 45 years old, Dominico-Haitian, elementary school, unemployed, National District, personal communication, August 15, 2015).

There are also cases in which Dominican or Haitian families who own the Dominican ID and present children of Haitian immigrants to the Electoral Central Board for their registration with the intention of “doing something good to help” without demanding money or another form of reward in return. This happens frequently when these families have some connection with the child –for example, godmothers or godparents– or when the child’s family are friends or neighbors, among others. Sometimes, there are cases of Haitian families who give their children as godchildren to Dominican families or Haitian families with legal documents for this same purpose.

A case that can serve to illustrate these scenarios is that of Graciela’s family, 20 years old. Although she was born in the DR, her parents were illegal Haitian immigrants, so they could not present her to request her birth certificate. To get this document, they asked their godmother –a Dominican– to present and register her; she did so without claiming any financial compensation from the family. In Graciela’s birth certificate, the names and surnames of her biological parents do not appear, but those of her Dominican godparents. Although she is not very happy about that, Graciela understands her parent’s decision. She states:

In most places, they ask for your ID to get a job. […] If you don’t have your birth certificate, you can’t have an ID, that’s why my mother did it. Now, with my ID, I can get a job. No one is going to say that I am Haitian or that my parents are Haitian. I’m not afraid. Therefore, I want to finish school and enroll in the university. I know other Haitian [children] who were born here and live with that fear, because they don’t have a birth certificate (Graciela, 20 years old, Dominico-Haitian, upper middle school, student, Sosúa, personal communication, September 18, 2015).

Another method of obtaining birth certificates also resulting in the loss of the biological parents’ surnames is the purchasing of documents that belonged to deceased children. Several interviewees reported that they knew Dominican families who agreed to exchange the documents of their deceased children. With these documents, obtained in exchange for a certain amount of money, the “new owners” acquire not only the Dominican nationality and its prerogatives but also the names, surnames, and date of birth of the deceased child. Such is the case of Sonia, 30 years old, who was 12 when her mother got the birth certificate of a girl who had died in the community where she lived. Sonia did not want to disclose the transactions’ amount but said her mother invested a good part of her savings on the purchase. Both mother and daughter moved to a sufficiently distant community to guarantee the confidentiality of the act performed. Like Graciela, Sonia expresses mixed feelings about her mother's act. She told us:

It was not easy for my mom. It’s like getting rid of your own daughter because your name no longer appears on her birth certificate, but someone else’s. […] Now that I have two children, I can understand it even more. It was a great sacrifice, but it was necessary, otherwise, I would have the same problems as all those Haitian [children], who are born here but are not Dominican; they are also not totally Haitian because they do not have Haitian documents (Sonia, 30 years old, brought to the DR in her childhood, primary school, retailer, Higüey, personal communication, September 18, 2015).

Other parents managed to obtain documents for their children with the support of local authorities (military or civil). This option seems to be more difficult since, in addition to financial compensation, it requires having the necessary contacts allowing direct or indirect access to sufficiently influential authorities to guide the decisions of local Electoral Central agencies.

A case that reflects the above is that of Tania, 26 years old and teacher in an elementary school. Although she was born in the DR, Tania did not get any document that established her link to the Dominican State. When her daughter was born, she did not want her to face the same difficulties as her, so she and her husband decided to do everything possible to obtain a birth certificate for the girl. Finally, through a family friend Dominican, representative of an influential political party in his community– who was friends with a local authority, they managed to obtain the so valuable document. Tania lamented the experience:

This is not fair; I was born here. Why do you think we had to spend so much money, beg so many people, and wait for so long [to get the certificate]? […] Because my parents are Haitian. It is not my daughter’s fault that my parents are Haitian […] If we had not done it, my daughter would have experienced the same problems that I am having now, and when she has her own children they would also have the same difficulty in getting their documents (Tania, 26 years old, Dominico-Haitian, upper middle school, teacher, Sosúa, personal communication, September 18, 2015).

Experiences such as those of Tania’s family reflect a part of the unfavorable consequences of restrictive policies in terms of obtaining nationality for the children of illegal Haitian immigrants and Dominico-Haitians. As already mentioned, obtaining Dominican documents for children aims to reduce the difficulties associated with their lack in various fields: social, political, labor, among others. It also ensures the permanence in the DR, where children have already been socialized and wherein, generally speaking, they will have more job opportunities. In this sense, nationality is considered by Haitian parents as a mechanism of protection and social participation for their Dominico-Haitian children.

Another strategy developed by Haitian families residing in the DR for their children is double school enrollment. This means that in several cases, in addition to the official Dominican school, many Haitian and Dominico-Haitian children attend unofficial Haitian schools (in the DR): in several areas, there are school establishments that, in addition to helping students with their Dominican school homework, offer Haitian education system programs in Creole and French. Although not recognized, these schools are somewhat tolerated by the Haitian and Dominican States; therefore, they do not grant any officially recognized degree or certificates to their students. In places where they are accessible, many Haitian families send their children to Dominican schools during the day and Haitian schools the remaining time.

Among other objectives, this strategy tries to anticipate an eventual return of the family to Haiti, and the consequences that it may have on children’s schooling. With double school enrollment, in case of a return/migration to Haiti, children would not have to start over or be delayed at lower levels than their peers of the same age. Adela, who sends her two children to the two unofficial schools, stated this:

If a child returns to Haiti and can only speak and read in Spanish, he will have to start from scratch. […] DR is slippery ground, they must be prepared for any eventuality (Adela, 38 years old, Haitian, elementary school, Sosúa, personal communication, September 18, 2015).

Also, some parents value the Haitian education system the most, as they consider it stricter; in their opinion, there students are more disciplined and learn better. In this regard, Adela’s husband, Jean-Louis, pointed out:

Look, even though [the school year] starts in August here and in September or [sometimes] October in Haiti, I still prefer Haitian school. […] In Haiti, students spend less time in school, but have better education. It is more serious, students learn more. It is common for children who come from Haiti to challenge other students of the schools here in mathematics […] I’ve seen it happening, even if they [in the DR] are in more advanced grades (Jean- Louis, 42 years old, Haitian, elementary school, gardener, Sosúa, personal communication, September 5, 2015).

Although not opinion necessarily shared among all members of the Haitian population in the DR, it is not uncommon for the Haitian school system to be praised and the Dominican system and students to be criticized.

Another reason that motivates parents to double enroll their children is that they want them to learn the official languages of Haiti in case of a possible return/migration to this country. This would not only allow for better school and/or work placement, but also facilitate their social assimilation. Judenel explained that he sends his children to a Haitian school in parallel to Dominican school so that they can “learn Creole and French, as well as Spanish,” because:

[…] You never know what children will want when they grow up. What if they decide to live in Haiti? What if the country develops in fifteen or twenty years? We must give children the best opportunities (Judenel, 35 years old, Haitian, elementary school, gardener and taxi driver; personal communication, September 8, 2015).

It should be noted that in addition to preparing for an eventual return to Haiti and providing children with various tools for greater possibilities of social and labor insertion in both DR and Haiti, double school enrollment also represents a family strategy linked to the work activities of parents. As already mentioned, the majority of Haitian immigrants are people of working age whose main motivation to migrate is working. For many parents, the fact that children attend two schools facilitates them a full working day. Adela, cited above, further explains:

My husband and I spend all day outside. There is no one else home. If it weren’t for the other [Haitian] school, there would be no one to take care of them when they are out of the Dominican school for the day […]. They come home [from the Dominican school], eat, change clothes and then go to the other [Haitian] school. My husband and I can have peace of mind, because they will be safe (Adela, 38 years old, Haitian, elementary school, Sosúa, personal communication, September 18, 2015).

As can be seen in this interview excerpt, the double enrollment of children is not only oriented towards the benefit of children themselves but also towards a higher socioeconomic performance of the family group as a whole. Although it is not a widespread practice to have any effect on the overall situation of the Haitian population in the labor market, in communities where it does exist, it can stimulate labor participation, especially of women with young children who would otherwise suspend their work activities to take care of their children.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The history of Haitian migrations to the Dominican territory and of the Dominican migration policies teaches us that the integration of Haitian immigrants and Dominico- Haitians into Dominican territory has two huge pitfalls: on the one hand, the racism and xenophobia prevailing in Dominican society towards the predominantly “black” Haitian population. On the other hand, those restrictive policies that seek to prevent their full participation in society. Particularly, by restricting the obtainment of immigration documents and the access to citizenship.

Facing the challenges of restrictive policies and deportations, Haitian families have responded by developing certain strategies. The first strategy outlined is basically aimed at getting the child to be part of the Dominican society as a member with full rights. The experiences of migrants in other contexts point towards the fact that nationality is not a panacea to prevent migrant children to be on equal terms as the population of non-migrant origin, but, without a doubt, it is a necessary condition for this to occur. In any case, the provisioning of nationality has certain advantages: 1) the uncertainty generated by restrictive policies ends, 2) those who have legal DR documents are no longer subject to deportation proceedings, 3) allows access to better jobs and salaries, and 4) allows full sociopolitical integration. The second strategy, the double school enrollment, points towards a better insertion in Haiti if family or child mobility to that country results necessary.

Future research should address in depth the link between discrimination, xenophobia and racism, and Dominican anti-immigrant policies. Although this link has been analyzed and presented in various publications before, evidencing multiple racist and xenophobic practices, there are still many aspects to further dissect. For example, questions such as “What factors influenced the approval of these anti-immigrant policies? To what extent would anti-immigrant policies be promoting more racism and xenophobia, among others?” should be addressed. Also, given that several families managed to get legal documents for their children, it would be useful to analyze the results of these in their social and labor assimilation against those who did not get them. Although those with citizenship are members with rights under legal terms in the Dominican society, it should be analyzed to what extent racial discrimination or other factors continue to operate as visible or invisible barriers against the integration of Haitian populations in the DR.

Given the high number of deportations and emigration of Haitians and their families after the 2013 Constitutional Tribunal ruling, future research could analyze the experience of children who moved to Haiti, depending on their presence or not in Haitian schools and the learning of Creole and French.

REFERENCES

Ariza, M. (2004). Obreras, sirvientas y prostitutas. Globalización, familia y mercado de trabajo en República Dominicana. Estudios Sociológicos, 22(1), 123-149. [ Links ]

Báez Evertsz, F. y Lozano, W. (1985). Migración internacional y economía cafetalera. Estudio sobre la migración estacional de trabajadores haitianos a la cosecha cafetalera en República Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Taina. [ Links ]

Bean, F. D., Brown, S. K. y Bachmeier, J. D. (2015). Parents without papers: The progress and pitfalls of Mexican American integration. Nueva York: Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Cámara administrativa de la Junta Central Electoral. (2007). Circular No. 17 . Recuperado de http://jce.gob.do/Noticias/tag/circular-17-2007 [ Links ]

Capdevila, L. (2004). Una discriminación organizada: las leyes de inmigración dominicana y la cuestión haitiana en el siglo XX. Tebeto: anuario del Archivo Histórico Insular de Fuerteventura (pp. 438-454). Fuerteventura: Cabildo Insular de Fuerteventura. [ Links ]

Castor, S. (1971). La ocupación norteamericana de Haití y sus consecuencias (1915- 1934). México: Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Castor, S. (1983). Migración y relaciones internacionales (el caso haitiano-dominicano). México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Cedeño, C. (1992). La nacionalidad de los descendientes de haitianos nacidos en República Dominicana. En W. Lozano (Ed.). La cuestión haitiana en Santo Domingo: migración internacional, desarrollo y relaciones inter-estatales entre Haití y República Dominicana, (137-143). Santo Domingo: FLACSO/ North-South Center University of Miami. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Reforma del Estado, y Comisionado de apoyo a la reforma y modernización de la justicia. (2010). Constitución de la República Dominicana proclamada el 26 de enero de 2010 y publicada en la Gaceta Oficial No. 10521, del 26 de enero de 2010 . Recuperado de http://www.caasd.gov.do/media/67694/libro%20constitucion%20abril2011.pdf [ Links ]

Del Castillo, J. (1978). La inmigración de braceros en la República Dominicana, 1900- 1930. Cuadernos del CENDIA, 262(7). Santo Domingo: Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo. [ Links ]

Del Castillo, J. (2005). La formación de la industria azucarera dominicana entre 1872 y 1930. Discurso de ingreso como miembro de número de la Academia Dominicana de la Historia. CLIO, (169), 11-76. [ Links ]

Domenach, H. (1986). Les migrations intra-caribéennes. Revue européenne des migrations internationales, 2(2), 9-24. [ Links ]

El Congreso Nacional. (2004). Ley No. 285-04, General de Migración. Recuperado de https://presidencia.gob.do/themes/custom/presidency/docs/gobplan/gobplan-15/Ley-No-285-04-Migracion.pdf [ Links ]

Escolano Giménez, L. A. (2010). La rivalidad internacional por la República Dominicana desde su independencia hasta la anexión a España (1844-1861). Tesis doctoral. Universidad de Alcalá: España. [ Links ]

Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) y Organización Internacional para las migraciones (OIM). (2004). Encuesta sobre los inmigrantes haitianos en República Dominicana. Santo Domingo. [ Links ]

Gaillard, R. (1981). Les Blancs débarquent, 1916-1917. La République autoritaire, Puerto Principe: Le Natal. [ Links ]

Lilón, D. (2010). Inmigración, xenofobia y nación: el caso dominicano. Revista del CESLA, 1(13), 287-300. [ Links ]

Lozano, W. (1998). Jornaleros e inmigrantes. Santo Domingo: FLACSO-INTEC. [ Links ]

Lozano, W. (2005). La paradoja de las migraciones. El Estado dominicano frente a la inmigración haitiana. Santo Domingo: Editorial UNIBE/FLACSO/SJRM. [ Links ]

Martínez, S. (1999). From Hidden Hand to Heavy Hand: Sugar, the State, and Migrant Labor in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Latin American Research Review, 34(1), 57-84. [ Links ]

Méroné, S. C. (2017). La integración de la población de origen haitiano en el mercado de trabajo de República Dominicana. Un análisis sociodemográfico. Tesis de doctorado. México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Michel, G. (2005). Panorama des relations haitiano-dominicaines. Puerto Príncipe: Le Natal. [ Links ]

Moral, P. (1978). Le paysan haïtien. (Étude sur la vie rurale en Haïti). Puerto Príncipe: Éditions Fardin. [ Links ]

Moya Pons, F. (1986). El Batey. Estudio socioeconómico de los bateyes del Consejo Estatal del Azúcar. Santo Domingo: Fondo para el Avance de las Ciencias Sociales. [ Links ]

Moya Pons, F. (1992). Las tres fronteras: Introducción a la frontera dominico-haitiana. En W. Lozano (Ed.). La cuestión haitiana en Santo Domingo. Migración internacional, desarrollo y relaciones inter-estatales entre Haití y República Dominicana (pp. 17- 32). Santo Domingo: FLACSO. [ Links ]

Oficina Nacional de Estadística (ONE) (2012). IX Censo nacional de población y vivienda 2010. Informe general. Recuperado de http://censo2010.one.gob.do/index.php?module=articles&func=view&ptid=2&p=6 [ Links ]

Oficina Nacional de Estadística (ONE). (2013). Primera Encuesta Nacional de Inmigrantes en la República Dominicana, ENI-2012. Informe general. [ Links ]

Open Society Foundations. (2010). Dominicanos de ascendencia haitiana y el derecho quebrantado a la nacionalidad. Informe presentado a la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos con motivo del 140° Período de Sesiones . Recuperado de https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/Dominican-Republic-Nationality-Report-ESP-20110805_0.pdf [ Links ]

Pedone, C., Echeverri, M. M. y Gil Araujo, S. (2014). Entre dos orillas. Cambios en las formas de organización de las familias migrantes latinoamericanas en España en tiempos de crisis global. En M. E. Zavala de Cosío y V. R. Gómez (Eds.). El género en movimiento. Familia y migraciones (pp. 109-138). México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Perdomo Cordero, N. (2016). Análisis crítico de la sentencia TC/0168/13. Memorias. Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe, 12 (28), 93-135. [ Links ]

Price-Mars, J. (1953). La République D´Haïti et la République Dominicaine. Les aspects divers d´un problème d´histoire de géographie et d´ethnologie. Puerto Príncipe: Editions Fardin. [ Links ]

Puyana Villamizar, Y. (2008). Políticas de familia en Colombia: matices y orientaciones. Trabajo Social, (10), 29-41. [ Links ]

Silié, R., Segura, C. y Dore Cabral, C. (2002). La nueva inmigración haitiana. Santo Domingo: FLACSO. [ Links ]

Tejada Yangüela, A. (2001). Bateyes del Estado. Encuesta socioeconómica y de salud de la población materno-infantil de los Bateyes Agrícolas del CEA, diciembre 1999. Santo Domingo: USAID. [ Links ]

Torre Cantalapiedra, E. y Anguiano Téllez, M. E. (2016). Viviendo en las sombras: estrategias de adaptación de familias inmigrantes mexicanas en Arizona, 2007-2015, Papeles de Población, 22(88), 171-207. [ Links ]

Turits, R. L. (2014). Un mundo destruido, una nación impuesta: La masacre haitiana de 1937 en la República Dominicana. Hispanic American Historical Review, 82(3), 589- 635. [ Links ]

Vargas Valle, E. D. y Coubès, M. L. (2017). Working and Giving Birth in the United States: Changing Strategies of Transborder Life in the North of Mexico, Frontera Norte, 29(57), 57-82. [ Links ]

3In this work, the expressions “DR-born children of Haitian parents” or “Dominico- Haitians” will refer to people born in the DR with at least one Haitian parent.

4By “Haitian children brought to this country in their childhood,” we refer to people born in Haiti who were taken to the DR by their parents when they were under 15.

5According to Del Castillo (2005), it can be said that the Civil War in the United States (1861-1865) impacted negatively on the sugarcane sector in Louisiana; that the Ten Years’ War in Cuba (1868-1878) drove a flow of Cuban businessmen and technicians to the Dominican Republic; that the Franco-Prussian War (1878) harmed the two main European producers of beet sugar and, finally, resulted in the signing of the Free Trade Agreement between the United States and the DR (1884) on sugar trade.

6Internally, political stability and the various laws and regulations favorable to investors in the sector, the availability of cheap land, natural conditions, among others, took part as factors of attraction of foreign capital at the precise time when the countries that produced sugar were undergoing different crises.

7Land tenure represented the main structural problem. This issue was never resolved after the country’s independence; on the contrary, it worsened with the fragmentation of the land (Moral, 1978). In addition to that, up until 1918 foreigners were forbidden to own land, making it difficult for foreign entrepreneurs to invest large-scale. As for short-term factors, it was mainly the explosive sociopolitical situation of the time (Castor, 1971; Moral, 1978).

9The lack of workforce partially resulted from the fact that, from the end of the 19th century, Dominican peasants abandoned the sugar cane work due to the low wages this sector paid (Del Castillo, 2005, 1978; Tejada Yangüela, 2001). In response to that, the sugar cane businessmen went first to the neighboring islands and then to Haiti to try and make up for the shortage of local labor.

10A term in Haitian Creole; refers to the destruction caused by rioters of everything related to the Duvalier dictatorship after its fall, including public works, companies or private properties whose owners supported the dictatorship.

12In the DR, it is necessary to present this document to vote, run for public office, enroll in a university, open a bank account, acquire or transfer a property, apply for a passport, access the social security system, make an affidavit before the courts, marry, divorce, birth registration of a child, among others.

13People whose parents used the so-called IDs –IDs issued by the companies in which the migrants worked– to declare them in the civil registry when they were children can be identified in the databases and considered without the right to Dominican birth certificate.

14It is worth mentioning that although it does not refer to the acquisition of the Dominico- Haitian nationality, Circular No. 7475 of the General Directorate of Migration to the Ministry of Education in 2012 compelled not to allow foreigners to access schools without the documentation that proves their legal stay in the country. Even if it says “foreigners” this circular would mostly affect the children of Haitians born in the DR.

15As noted above, from this age on, you need to present an ID in order to carry yourself without restrictions in different areas.

16The criteria used to determine which households belong to this population are that one of the parents was born in Haiti, or that one of them was Dominico-Haitian.

18Those in which people with broader kinship ties live, unlike in a nuclear home; that is, you can find grandparents, grandchildren, cousins, uncles, or some other relatives.

Received: September 03, 2017; Accepted: March 29, 2018

texto em

texto em