Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.10 Tijuana 2019 Epub 01-Ene-2019

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i36.2005

Article

Social Vulnerability and Health Needs of Immigrant Population in Northern Chile

1Universidad Católica del Norte, Chile, mramirezs@ucn.cl

2Universidad Católica del Norte, Chile, johanarivera@gmail.com

3Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile, margarita.bernales@gmail.com

4Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile, bcabieses@udd.cl

It was proposed to know the health vulnerability and health care needs of immigrants in Chile, through a qualitative exploratory study. The findings suggest that their vulnerability would be due to their irregular status, precarious work and low incomes, when they do. Health conditions are common morbidity, mental and reproductive health. Acculturation and a positive attitude towards self-care would be protective factors. An important barrier to access is the illegal status of some immigrants; as the ignorance of the Chilean health system. It is suggested to socialize health policies for migrants and to expand targeted strategies for their health care.

Keywords: immigrants; primary health care; health vulnerability; Latin America; Chile

Se propuso conocer la vulnerabilidad sanitaria y necesidades de salud de personas inmigrantes en Chile, a través de un estudio cualitativo exploratorio. Los hallazgos indican que su vulnerabilidad estaría dada por su condición irregular, trabajo precario y bajos ingresos, cuando lo tienen. Las afecciones de salud son morbilidad común, de salud mental y reproductiva. La aculturación y actitud positiva hacia el autocuidado serían factores protectores. Importante barrera de acceso es la situación ilegal de algunos inmigrantes; y el desconocimiento del sistema sanitario chileno. Se sugiere socializar políticas sanitarias para migrantes y expandir estrategias dirigidas para su atención de salud.

Palabras clave: inmigrantes; atención primaria de salud; vulnerabilidad sanitaria; América Latina; Chile

Introduction

Chile has been a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) since 2010. In 2012 it had an estimated population of 17.4 million, and its GDP per capita was $21,990 USD in 2013 ( OECD, 2015 ). Consequently, the country has become a pole of attraction for migration from neighboring countries, which increased from 83,000 in 1982 to 411,000 in 2014 (Ministry of the Interior, 2014). According to the 2014 annual directory on migration statistics published by the Department of Foreigners and Immigration, part of the Ministry of the Interior and Public Security, immigrants are mostly female (52.9%) and come from Peru (31%), Argentina (16%), and Bolivia (8.8%) ( Ministry of the Interior, 2016 ). This phenomenon has been described as South-South migration in Latin America, meaning that it occurs between bordering or nearby countries within the Southern Cone. In this sense, although Argentina has been identified as a receiving country, Brazil and Chile also exhibit the same profile ( Marroni, 2016 ) and in Chile, the phenomenon has been characterized by significant feminization, as reported by various authors ( Acosta González, 2013 ; Elizalde, Thayer, & Córdova, 2013 ; Mora, 2008 ). Studies on migration in Latin America report that these populations travel from places with poor living conditions to places with stronger economies but greater inequality, in search of better opportunities. As a result, and paradoxically, these populations become part of the most vulnerable groups in receiving countries ( Vásquez-De Kartzow, Castillo-Durán, & Lera, 2015 ).

It should be noted that immigrants do not hold citizen status in Chile. They are able to apply for citizenship once they have held a temporary resident visa for 5 years ( Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Chile, 2011 ). Furthermore, Chilean law only guarantees health coverage to people with an employment contract, either through public insurance (National Health Fund [Fonasa]) or private insurance (Social Security Health Institution [Isapre]). Otherwise, they can access the public system –or any healthcare system– as “destitute people” (indigentes) provided they pay the costly contributions privately. Fonasa, as a provider of public health insurance, offers first-class healthcare through Family Health Centers (known as Cesfam) across the country, which are managed at a municipal level ( Vásquez-De Kartzow, 2009 ) and governed by the same regulations. As far as immigrants’ healthcare and social security situation is concerned, the 2013 National Socio-Economic Characterization Survey (CASEN) found that most are enrolled in a health insurance system; 68.7% are registered in the public system or Fonasa; 18.1% are members of the private system or Isapre, and finally, 8.9% reported not being enrolled in any healthcare system ( Ministry of Social Development, 2013 ). According to Cano, Contrucci, and Pizarro (2009) , “The high proportion of contributors in the public system is, in part, promoted by the current migration policy in Chile, under which it is necessary to have an employment contract to access a permanent resident visa”. However, a number of immigrants with irregular status have still not been clearly identified, as 30% of immigrants in the Metropolitan Region were undocumented ( Vásquez-De Kartzow, 2009 ).

Castañeda et al. (2013) identify immigrant status as a social determinant of health, and the psychosocial characterization of the immigrant population’s health and living conditions in Chile was described by Cabieses (2012) as a population primarily made up of young women from ethnic minorities. Migrants from lower socio-economic strata exhibit similar characteristics to Chileans in the same stratum with regard to unemployment and poverty, but are younger. According to Cabieses, Tunstall, and Picket (2015) , the group is socially complex and heterogeneous, but also particularly vulnerable. It should be noted, however, that few studies have been published on the healthcare needs of the immigrant population in Chile. Cabieses, Tunstall, Pickett, and Gideon (2012) found that immigrants’ access to primary-level benefits differs, in part, from care received by Chilean citizens because the immigrant population displays higher rates of prenatal and gynecological care and lower use of child checkups.

This paper describes the main findings of a qualitative study nested within a larger research project (Fondecyt 11130042 “Developing intelligence in public health for international immigrants in Chile” [“Desarrollando inteligencia en salud pública para inmigrantes internacionales en Chile”]) approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Desarrollo (approval certificate 2013-38, dated May 17th, 2013), which seeks to contribute to knowledge of international immigrants’ healthcare situation in Chile. The study reports the results of a qualitative exploratory case study conducted in the commune of Coquimbo, northern Chile, between August 2014 and May 2015, the purpose of which was to explore health vulnerability among the international immigrant population that uses primary healthcare, and identify their healthcare needs and how they perceive the service in primary healthcare centers in the commune. With this in mind, the study included immigrants using two primary healthcare centers, and interviews were conducted with the directors of these centers and the mayor of the commune, who are responsible for managing primary healthcare institutions.

Materials and methods

This qualitative study was conducted within the framework of a constructivist model and follows the methodological guidelines provided by Amezcua and Gálvez Toro (2002) , using the case study proposed by Lund (2014) . Information for content analysis was obtained from transcripts collected through focus groups with immigrants from the commune of Coquimbo who used the health system at the primary care level, and semistructured interviews with two types of key informants associated with the situation under study, with the goal of gaining insight into the perspective of those familiar with the healthcare context, such as the directors of primary healthcare centers and the mayor of the commune.

Criterion sampling was performed using sampling methods laid down by Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2014) . The Family Health Centers were chosen based on the directors’ willingness to take part in the study and participants were selected according to three criteria: 1) international immigrants who used two Family Health Centers in the commune of Coquimbo, 2) the willingness of the directors of these centers, and 3) the mayor of the commune of Coquimbo as the authority responsible for administering primary healthcare. Subjects had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) be over 18 years of age; 2) have lived in Chile for at least a year; 3) have some connection to the Family Health Centers studied; 4) have read and agreed to the informed consent form; 5) have signed a document attesting that they are participating on a voluntary, anonymous, and unpaid basis. Once the informed consent form was explained and signed, the directors of the health centers and the mayor were interviewed following the interview guide in a quiet and private space. Two focus group sessions were held with immigrants who agreed to participate, one at each health center. Audio recordings were made of the conversations, with no record of the participants’ identities. These were then transcribed verbatim in Microsoft Word format by trained personnel.

The content of the texts was analyzed by establishing categories as described by Amezcua and Gálvez Toro (2002) . Afterwards, a semantic analysis – an analysis of the texts’ meaning – was performed, in which the texts were interpreted based on the participants’ discourse and in line with the general structure of the interview guide to provide an overview of the topic. The questions in the guide are outlined in Table 1, as are the relevant categories and emergent codes. The categories were defined following Taylor and Bodgan’s coding method based on keywords and with the aid of the Atlas.ti program, with 56 tags generated first of all ( Amezcua & Gálvez Toro, 2002 ).

Table 1. Codebook, objectives, description of interview guide/focus groups, categories and emergent codes

| Objectives | Interview guide/focus | Category | Emergent codes | Extracts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| groups: what was asked? | ||||

| Explore the social | How old are you? | Prior sociocultural | The high cost of living | “I’ve dreamt of leaving my country to get |

| vulnerability of | Which sex are you? | characteristics. | leads to poor living | ahead” (E149B, personal communication, |

| the international | What is your marital | conditions for | October 2014-March 2015). | |

| immigrant | status? | Motivation for | migrants. | |

| population using | What is your level of | migrating. | “I’m seeking a better life for my family” | |

| primary | schooling? | Intervening social | (E729D, personal communication, October | |

| healthcare centers | What is your country of | View of Chile. | factors: | 2014-March 2015) |

| origin? | ||||

| How long have you been | Characteristics of | Support networks. | “We spend a lot, ha, ha – what I mean is we | |

| living in this commune? | immigrants and context: | can’t save anything”, “I live with […] women | ||

| Why did you come to | Process of assimilation | from foreign countries, we don’t have social | ||

| live in Chile? Give 3 | Low level of education. | to the Chilean culture | security […] the money we earn is just enough | |

| main reasons. | as a protective factor. | for the rent, nothing else” (E226C, personal | ||

| How many people live in | Unstable employment | communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||

| your household? | situation (no health | Value placed on | ||

| Do you have any | insurance). | migrating professional | “It’s tough. […] adapting is tough. Cultural | |

| children? Did you work | workers. | pressure, meaning that the dominant culture | ||

| last week? | Low income | always takes precedence over the immigrant’s | ||

| Do you have a formal | culture, makes it difficult to engage and form | |||

| employment contract? | Overcrowding, shared | relationships” (E640C, personal | ||

| Are your immigration | housing | communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||

| documents current? | ||||

| Do you have health | Discrimination | “We get together on public holidays or | ||

| insurance? | (positive/negative). | Sundays, for instance, but sadly, we don’t have | ||

| What is your | a place, a room, that’s what we need […] we | |||

| household’s tota | may be able to get one though” (E149B, | |||

| monthly income? How | personal communication, October 2014-March | |||

| much of this do you send | 2015). | |||

| back to your country | ||||

| each month? | “Leaving the family is a difficult process, isn’t | |||

| it? … Learning from you, because when you | ||||

| arrive in a new culture, you don’t know what’s | ||||

| acceptable and what’s not, the norms, so much, | ||||

| there’s so much in a culture” (E640C, personal | ||||

| communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “Well, the people I’ve treated here, 2 | ||||

| immigrants with immigrant children, a | ||||

| Bolivian woman and a Mexican woman – yah | ||||

| – are in very, very difficult situations because | ||||

| they haven’t got a professional degree” | ||||

| (E640C, personal communication, October | ||||

| 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “I think being a professional gives you certain | ||||

| advantages because you have a degree, or | ||||

| access, obviously, although the conditions in | ||||

| my field are not the best” (E640C, personal | ||||

| communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| Explore the | Do you think immigrants | Intervening factor: | Intervening factor: | “When they enter the system, they have |

| perception of | know their rights | exactly the same benefits as the Chilean | ||

| immigrants | know their rights | Migration and health | Intervening factor: | population, they access the system as users, |

| regarding the care | Chile? | policies for migrants | international | like those who take up employment […] there |

| received at | agreements, the | is no discrimination of any kind in that sense” | ||

| primary | Chilean health system, | (E949C, personal communication, October | ||

| healthcare centers. | and the health needs | 2014-March 2015). | ||

| and characteristics of | ||||

| the immigrant | “Well, when I was giving birth, I was kind of | |||

| population and policy | scared because I didn’t know if I’d be charged, | |||

| implementation. | perhaps a million, I don’t know how much […] | |||

| that’s what I was told, it costs about that much | ||||

| […] and I don’t have that kind of money, I’m a | ||||

| single mother” (E226C, personal | ||||

| communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “In the last participatory diagnosis I saw, | ||||

| which was pretty well done and is from 2013, | ||||

| no mention was made of the immigrant | ||||

| population” (E949C, personal communication, | ||||

| October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “We haven’t quantified it, we don’t have any | ||||

| current measurements because the system | ||||

| gives you numbers, and we’re working on a | ||||

| case-by-case basis” (E949C, personal | ||||

| communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| Explore the | How would you describe | Characterization of | The high cost of | “Likewise4 , in my own case, I’m considering |

| perception of | the relationship between | healthcare: | healthcare leads some | traveling with my daughter, perhaps to Bolivia, |

| immigrants | immigrants and the | migrants to prefer their | my country, to treat her eyesight, get her lens | |

| regarding the care | health center or clinic? | Access to healthcare. | own country’s system. | prescription looked at, and there’s the dental |

| received at | Why? | problem too, in this country it’s too expensive” | ||

| primary | Failings (waiting times, | (E149B, personal communication, October | ||

| healthcare centers. | lack of space). | 2014-March 2015). | ||

| “Hmm! Unlike the health system we have back | ||||

| in our country, which gives you greater | ||||

| coverage for medicine, specialist care, | ||||

| financially speaking, because you pay very | ||||

| little in Colombia, depending on your social | ||||

| background, and it’s not like that here, here | ||||

| everything costs money […] the thing is that | ||||

| Chile is a very expensive country in every | ||||

| respect” | ||||

| (E640C, personal communication, October | ||||

| 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| Identify the health | How would you describe | State of health. | Similar medical | “I have a vision problem, that’s the prime |

| needs of the | your current state of | conditions to the | concern for me” (E149B, personal | |

| international | health? | Healthcare needs. | Chilean population. | communication, October 2014-March 2015). |

| immigrant | What are your main | |||

| population using | health needs at the | Mental health issues. | “Because I come for healthcare for him, I come | |

| primary | moment? | for general treatment, care for my son and | ||

| healthcare. | What are your family’s | Intervening factor: | stomach pain, that’s the thing” (E729D, | |

| main health needs at the | personal communication, October 2014-March | |||

| moment? | Self-care in sexual | 2015). | ||

| What are the main living | health and diet. | |||

| and health needs of the | ||||

| immigrant population in | “Checkups for the boy and my wife who […] | |||

| your commune? | gave birth not long ago” (E329C, personal | |||

| communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “Yah, my mom had surgery a little while ago, | ||||

| yah, she had everything removed, the colon is | ||||

| our biggest problem, and all my sisters, my | ||||

| mom, and I all [suffer] from that” (E529A, | ||||

| personal communication, October 2014-March | ||||

| 2015). | ||||

| “Some people with depression, because when | ||||

| they come here for the first time, in the first | ||||

| few months […] it also depends on the | ||||

| nationality, what I can say is that mental health | ||||

| is closely associated with acculturation, in my | ||||

| own case” (E640C, personal communication, | ||||

| October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “I ask for help; that is to say, I ask my sisters to | ||||

| come with me to the […] to be seen – yah – to | ||||

| see what’s up, what’s the matter” (E529A, | ||||

| personal communication, October 2014-March | ||||

| 2015). | ||||

| “The most important thing is making sure I | ||||

| don’t get HIV some day […] that’s most | ||||

| important! Yes, that’s the main thing really” | ||||

| (E529A, personal communication, October | ||||

| 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “I had a good diet in my country, then came to | ||||

| another country to have a poor diet” (E640C, | ||||

| personal communication, October 2014-March | ||||

| 2015). | ||||

| Explore the | How has this health | Internal policies of each | Adaptation | “If we go and visit them, they’re kind of |

| perception of | center adapted to | health center | mechanisms to treat | reluctant to receive people. So they’re really |

| immigrants | respond to the specific | migrants. | quite particular, but all the same, we try to | |

| regarding the care | needs of the immigrant | ensure the different health teams work where | ||

| received at | population living in this | Administrative staff. | they should” (E1049C, personal | |

| primary | commune? How have | communication, October 2014-March 2015). | ||

| healthcare centers. | these changes been | Direct care. | ||

| assessed? | ||||

| Explore the | Could you describe the | Health policies. | Difficulties associated | “They won’t rent to us because we’re |

| perception of | process by which | with discrimination | foreigners, they say we’ll damage their | |

| immigrants | patients receive an | Migration policies. | and the normalization | property or make a huge mess” (E226C, |

| regarding the care | appointment at the health | of conditions of | personal communication, October 2014-March | |

| received at | center? Is it different for | Access to primary health | inequality | |

| primary | Chileans and | centers. | “So it’s like we don’t have the same rights as | |

| healthcare centers. | immigrants? In what | those who were born here, in Chile” (E226C, | ||

| way? | personal communication, October 2014-March | |||

| How might these | 2015). | |||

| differences affect | ||||

| immigrants’ health? | “The lower one’s level of education, the more | |||

| discrimination there is. If you’re more highly | ||||

| educated, there’s less, but you can still sense it, | ||||

| I mean, it’s more subtle, I think, it’s more | ||||

| subtle” (E640C, personal communication, | ||||

| October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| Explore the | Do you have any | Suggestions for | Migrant | “I think that, maybe, the clinic could bring |

| perception of | suggestion to improve | improvement: | demographics. | together the immigrants from my country and |

| immigrants | the health service for | […] to improve care” (E149B, personal | ||

| regarding the care | immigrants at the health | Greater inclusion. | Understand the | communication, October 2014-March 2015). |

| received at | center? | sociodemographic | ||

| primary | Social security that does | profile and, possibly, | “It would be like legalizing or helping | |

| healthcare centers. | not depend on an | detect special needs. | foreigners more, so we have social security | |

| employment contract. | regardless of whether we have an employment | |||

| contract” (E226C, personal communication, | ||||

| October 2014-March 2015). | ||||

| “[What] we need is a reliable record of which | ||||

| […] how many […] which population we’re | ||||

| talking about and the true demographic | ||||

| characteristics of that population, how many | ||||

| are children, how many are elderly […] and we | ||||

| also need to know who is covered by the public | ||||

| health system and who isn’t, who receives | ||||

| healthcare privately or through social aid” | ||||

| (E1152A, personal communication, October | ||||

| 2014-March 2015) | ||||

| Explore the | In general, how would | Current healthcare | Remove barriers that | “The wait time is too long, we wait too much, |

| perception of | you describe primary | needs | hinder the operation of | we need to be seen as soon as possible and we |

| immigrants | healthcare in the | the Family Health | have to wait a long time” (E149B, personal | |

| regarding the care | Coquimbo commune? | Center (Cesfam). | communication, October 2014-March 2015). | |

| received at | ||||

| primary | In your opinion, has the | Clarity in | “You don’t receive care for the problem you | |

| healthcare centers. | health center managed to | implementing key | have” (E529A, personal communication, | |

| adapt to the needs of | ordinances to run the | October 2014-March 2015). | ||

| immigrants? How? | center. | |||

| “Physically you don’t have the space to do it | ||||

| (to care for patients in a special manner), so | ||||

| now we have a problem whereby professionals | ||||

| have to take turns in the same examination | ||||

| room, so it can’t grow because it’s limited by | ||||

| everything and a load of issues” (E949C). |

Source: Compiled by authors.

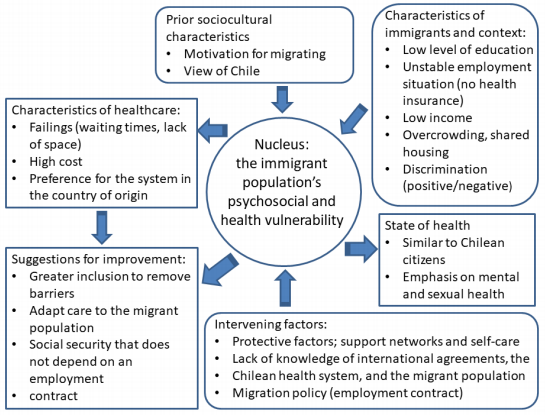

Seven categories of relevant themes were identified through associative schemata, one of which is the nucleus. According to Gomes Campo and Ribeiro Turato (2009) , relevant categories are statements that make it possible to answer the research questions. In this study, the categories were immigrants’ social conditions and context, their state of health and intervening factors, their perception of healthcare and macrostructural factors associated with public policies, and the nucleus identified as the main category is the immigrant population’s psychosocial and health vulnerability. The study also incorporated emergent codes from participants’ discourse in relation to the themes explored and which were not directly researched. Figure 1 illustrates this.

Source: Compiled by authors

Figure 1. Thematic categories associated with the immigrant population’s psychosocial risk in Coquimbo, Chile, 2014-2015

In order to explore the topic in greater depth, the “Social and health vulnerability of international immigrants using primary healthcare in a city in northern Chile” was analyzed using the conceptual model proposed by Lund (2014) , which entails developing a vision of the topic from four kinds of perspective: 1) specific and concrete, 2) specific and abstract, 3) general and concrete, 4) general and abstract. For this last interpretation, deductive and inductive reasoning was used dialectically, thus contributing to the construction of knowledge as the researcher draws on intuition and prior knowledge of the topic ( Gomes Campo and Ribeiro Turato, 2009 ).

Results

Caracterization of participants

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants: eight international immigrants, two directors of Family Health Centers, and the mayor of Coquimbo commune. The group of immigrants comprised mainly single women from Colombia, Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, and the Dominican Republic, who worked as waitresses or domestic workers and, in general, had completed secondary education or obtained a vocational associate degree; just one had a professional degree from a university.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characterization of participants

| Nationality | Sex | Age | Marital status | Education | Profession/Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chilean | Female | 49 | Married | Professional degree | Director of Health Center |

| Chilean | Male | 49 | Single | Professional degree | Director of Health Center |

| Chilean | Male | 52 | Married | Professional degree | Mayor of Coquimbo commune |

| Bolivian | Female | 49 | Single | Secondary school | Domestic worker |

| Colombian | Female | 26 | Single | Vocational associate degree | Waitress |

| Colombian | Male | 29 | Single | Vocational associate degree | Fish merchan |

| Argentine | Female | 29 | Single | Secondary school | Sales representative |

| Dominican | Female | 29 | Single | Vocational associate degree | Waitress |

| Colombian | Female | 26 | Single | Secondary school | Waitress |

| Colombian | Female | 40 | Single | Professional degree | Psychologist |

| Peruvian | Female | 49 | Single | Secondary school | Domestic worker |

Source: Own work.

Case description and analysis

The “Social and health vulnerability of international migrants using primary healthcare in a city in northern Chile” is described below on the basis of the information collected, and is supported by quotes from the participants. In turn, this situation is analyzed from four perspectives, which are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Four-dimensional analysis of the situation “Social and health vulnerability of international migrants in a city in northern Chile”

| Dimension | Concrete | Abstract |

|---|---|---|

| Specific | Social and demographic information on migrants, social determinants of health, health risk factors and health problems. Protective factors: adaptation and selfcare. | Access and healthcare: conditions, migratory/work/social security status of people/users, level of information (or misinformation) among users and healthcare providers, quality of care. |

| General (structural and regulatory) | Chilean health system. Public health system and municipal primary healthcare. | Migration policies. Health policies and local strategies for healthcare. Right to health in Chile. |

Source: Own work.

Firstly, concrete and specific aspects are presented and analyzed: the social and demographic characteristics of migrants, social determinants of health, health risk factors, and health problems of the group studied. In order to characterize participating immigrants and their context, it is necessary to ascertain their current occupations and health needs. The motivational factors influencing migration are associated with the pursuit of job opportunities to improve migrants’ economic situation and personal development: “I’ve dreamt of leaving my country to get ahead” (Female interviewee 1, personal communication, November 2014), “a better life for my family” (Female interviewee 7, personal communication, December 2014). Migrants’ perception of the economic conditions in Chile also plays a part in their decision to emigrate. This has been shown in the realities described here and by Marroni (2016) , who stated that globalization drives population mobility between countries with disparate levels of development and the growth of diverse labor markets, and is part of the South-South migration phenomenon.

Sadly, job expectations are not always met in receiving countries. The participants’ accounts reveal social conditions such as the lack of health insurance, low qualifications, low wages, sporadic and informal work (such as domestic services, traders, prostitution, waiting tables, etc.) and a need to share housing with one’s core social network (children, family members or friends). Several interviewees are single mothers and descended from Afro-Americans, and are separated or in dysfunctional family relationships: “Well, the people I’ve treated here, two immigrants with immigrant children, a Bolivian woman and a Mexican woman – yah – are in very, very difficult situations because they haven’t got a professional degree” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014). Their poor saving capacity limits their ability to send money back to their country as a result of high living costs: “We spend a lot, ha, ha – what I mean is we can’t save anything” (Female interviewee 2, personal communication, October 2014). The participants’ descriptions clearly support the assertion made by Elizalde et al. (2013) in the sense that migrants are often devalued in the workforce; the skills they acquired in their countries of origin are not recognized and they resort to less stable work.

So far, the study suggests that the immigrant population using primary healthcare in the Coquimbo commune exhibits social and health vulnerability, primarily as a result of their working and socioeconomic conditions. This is in line with Urzúa, Heredia, and Caqueo-Urízar (2016) who establish a link between income and quality of life among immigrants in northern Chile, along with other factors like one’s family situation and relationship status, which also influence immigrants’ life trajectories according to Stefoni, Bonhomme, Hurtado, and Santiago (2014) . Similar conditions of psychosocial vulnerability have previously been described among migrants from other Latin American countries ( Elizalde et al., 2013 ).

As far as health needs and problems are concerned, the interviewees mention common self-reported conditions affecting themselves and close family members, such as colds, colon disorders, anxiety, obesity, vision problems, gallbladder problems, or high blood pressure: “I have a vision problem, that’s the prime concern for me” (Female interviewee 1, personal communication, November 2014), “I come for healthcare for him, I come for general treatment, care for my son and stomach pain, that’s the thing” (Female interviewee 7, personal communication, December 2014), “checkups for the boy and my wife who […] gave birth not long ago” (Male interviewee 3, personal communication, March 2015), “yah, my mom had surgery a little while ago, yah, she had everything removed, the colon is our biggest problem, and all my sisters, my mom and I all [suffer] from that” (Female interviewee 5, personal communication, October 2014).

Some immigrants and one Family Health Center director note cases of depression and symptoms such as irritability and fatigue. They consider themselves at risk due to their poor ability to adapt to a change in lifestyle: “Some people with depression […] because when they come here for the first time, in the first few months” (Male interviewee 9, personal communication, October 2014), “it also depends on the nationality, what I can say is that mental health is closely associated with acculturation, in my own case” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014). These aspects of mental health support the meta-analysis conducted by Jurado et al. (2016) on the migrant population at a global level. Factors affecting emigrant vulnerability to the development of common mental disorders are their country of origin, being female, having a low level of education and social status, and one’s family situation and relationship status, as well as factors associated with the migration process such as language, acculturation, the need to migrate, and migration planning. Similarly, discrimination is identified as an aspect that may modulate the perception of mental issues such as high sensitivity and depression, as described by Burman (2016) in her study on Peruvian migrants in Santiago de Chile.

Positive intervening factors were identified as emergent categories and are associated with the existence of support networks and self-care. As far as social acceptance and discrimination are concerned, the feeling of marginalization reported by immigrants is inconsistent with the directors’ claim that Chileans do not discriminate against migrants. On the one hand, one immigrant stated, “They won’t rent to us because we’re foreigners, they say we’ll damage their property or make a huge mess […] so it’s like we don’t have the same rights as those who were born here, in Chile” (Female interviewee 2, personal communication, October 2014), while another claimed, “The lower one’s level of education, the more discrimination there is. If you’re more highly educated, there’s less, but you can still sense it, I mean, it’s more subtle, I think” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014). On the other hand, a director explained, “When they enter the system, they have exactly the same benefits as the Chilean population, they access the system as users, like those who take up employment […] there is no discrimination of any kind in that sense” (Male interviewee 9, personal communication, October 2014).

Acculturation is the process that leads human groups to integrate culturally into a society. In that sense, Berry’s (2008) model posits four strategies from the perspective of a minority group integrating into a society: 1) assimilation: the minority group does not wish to preserve its culture but rather become permanently absorbed into the new one; 2) separation: the new group does not wish to lose its own culture and avoids engaging with others; 3) integration: both groups wish to preserve their own cultures, but do engage with each other; and 4) marginalization: there is little interest both in preserving one’s own culture and in engaging with others. Acculturation strategies are important for migrants’ adaptation process and mental health ( Urzúa et al., 2016 ). For the study participants, the process of assimilating to the Chilean culture included two components: on the one hand, a tendency toward separation, as a result of the ability to construct networks with other immigrants to solve or deal with problems: “We get together on public holidays or Sundays, for instance, but sadly, we don’t have a place, a room, that’s what we need […] we may be able to get one though” (Female interviewee 1, personal communication, November 2014). The second component is assimilation through efforts to adapt: “Leaving the family is a difficult process, isn’t it? […] Learning from you, because when you arrive in a new culture, you don’t know what’s acceptable and what’s not, the norms, so much, there’s so much in a culture […] adapting is tough. Cultural pressure, meaning that the dominant culture always takes precedence over the immigrant’s culture, makes it difficult to engage and form relationships” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014). Regarding the capacity for integration, Urzúa, Vega, Jara, Trujillo, and Muñoz (2015) remark that social integration boosts a group’s quality of life in their study on immigrants in northern Chile. However, according to Berry (2008) , this strategy requires the participation of the receiving society – in this case, Chileans. In this sense, integration may be facilitated when a positive view is taken of immigrants’ professional qualifications; one user of a health center, an immigrant with a professional degree, stressed the value of higher or professional qualifications: “I think being a professional gives you certain advantages because you have a degree, or access, obviously, although the conditions in my field are not the best” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014).

Self-care is a reflection of participants’ positive attitude and may act as a protective factor for health, as participants pointed to concerns over improving their diet, skills for handling stress and anxiety, and guarding against sexually transmitted infections (STIs): “I think that having healthy habits, for example, practicing sport and eating a balanced diet that combines foods from different food groups […] that’s what I try to do” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014), “the most important thing is making sure I don’t get HIV some day […] that’s most important! Yes, that’s the main thing really” (Female interviewee 5, personal communication, October 2014). They also showed a willingness to receive psychological care at the Family Health Center to overcome a difficulty or contingent problem: “I ask for help; that is to say, I ask my sisters to come with me to the Community Mental Health Center (Cosam) […] to be seen, yah, to see what’s up, what’s the matter” (Female interviewee 5, personal communication, October 2014). This positive attitude toward self-care was also described by Cabieses et al. (2012) , who point to a greater use of prenatal and gynecological services by migrants compared to the Chilean population, which should be taken into account by healthcare staff to encourage preventive behavior both among migrants and the broader community. Studies conducted on the immigrant population in the United States show that immigrants exhibit less risk of diabetes in young people and less risk of STIs in Latin American women ( Jaacks, L.M. et al., 2012 ; Ojeda et al., 2009 ). It is possible that a sense of having less access to healthcare leads to a positive self-care attitude. In this sense, diet should be pointed out as a protective factor; Concha (2015) remarks that certain immigrants (for example, Peruvians) eat a more balanced diet than the Chilean population.

A second level of analysis – from a specific and abstract perspective – identifies aspects associated with healthcare and access to such care. In this regard, the study brings to light scant knowledge of social and health benefits, both among immigrants and care providers. One finding is an urgent need for records of migrant users and the care they receive. Directors and migrants themselves state that health services have little information on immigrant users or beneficiaries, and point to immigrants’ lack of knowledge of the Chilean healthcare system. This is illustrated by these comments by the mayor of the commune of Coquimbo:

We haven’t quantified it, we don’t have any current measurements because the system gives you numbers and we’re working on a case-by-case basis […] we need a reliable record of which […] how many […] which population we’re talking about and the true demographic characteristics of that population, how many are children, how many are elderly […] and we also need to know who is covered by the public health system and who isn’t, who receives healthcare privately or through social aid” (Male interviewee 11, personal communication, January 2015).

One Family Health Center director remarked that “in the last participatory diagnosis I saw, which was pretty well done and is from 2013, no mention was made of the immigrant population” (Male interviewee 2, personal communication, January 2015). Although health officials are aware that there is a significant number of migrants, they lack any special health strategies geared toward this population.

Moreover, it is clear that migrants are unfamiliar with the Chilean health system: “Well, when I was giving birth, I was kind of scared because I didn’t know if I’d be charged, perhaps a million, I don’t know how much […] that’s what I was told, it costs about that much […] and I don’t have that kind of money, I’m a single mother” (Female interviewee 10, personal communication, February 2015). These examples are in line with Burgos and Parvic (2010) ; a lack of information on healthcare and health benefits can jeopardize rights when access to care is restricted, whether this due to migrant beneficiaries’ unfamiliarity with the system, health workers’ lack of information on migrants’ rights, or fear on the part of migrants with irregular status.

Healthcare costs in Chile are high, notably because the public system is unable to meet demand. In the study, participants cited the lack of their own resources to cover medical costs, and congestion in the health service due to high demand: “The wait time is too long, we wait too much, we need to be seen as soon as possible and we have to wait a long time” (Female interviewee 1, personal communication), “you don’t receive care for the problem you have” (Female interviewee 5, personal communication, November 2014), “physically you don’t have the space to do it, so now we have a problem whereby professionals have to take turns in the same examination room, so it can’t grow because it’s limited by everything and a load of issues” (Male interviewee 2, personal communication, October 2014).

In light of this, it was observed that migrant users prefer the service provided by the health system in their country of origin, primarily due to the costs, form of healthcare, conditions under which referrals are made, and state-sponsored dental and drug coverage: “Likewise, in my own case, I’m considering traveling with my daughter, perhaps to Bolivia, my country, to treat her eyesight, get her lens prescription looked at, and there’s the dental problem too, in this country it’s too expensive” (Female interviewee 1, personal communication, November 2014), “Hmm! Unlike the health system we have back in our country, which gives you greater coverage for medicine, specialist care, financially speaking, because you pay very little in Colombia, depending on your social background, and it’s not like that here, here everything costs money […] the thing is that Chile is a very expensive country in every respect” (Female interviewee 6, personal communication, November 2014). It is clear that the health sector has not sufficiently adapted to meet the needs of this population, leading to a preference for the healthcare system in the country of origin.

The third dimension of the analysis is general and concrete, which in this case refers to the way the Chilean health system is organized and how local strategies for migrant healthcare are developed. In this regard, the Family Health Center directors and the mayor of the commune expressed their interest in addressing community demand and a willingness to organize consultations with other services in cases of violence or where social work is required: “If we go and visit them, they’re kind of reluctant to receive people. So they’re really quite particular, but all the same, we try to ensure the different health teams work where they should” (Female interviewee 10, personal communication, February 2015). Although this shows a concern, on an invidual level, for providing care for migrants, fulfilling their needs calls for tailored strategies to treat the most prevalent conditions (greater mental health coverage, sexual health checkups and guidance) and psychosocial support for life-threatening limit-situations. Some approaches, particularly with respect to children, were described by Vásquez-De Kartzow (2009) . As for strategies to improve the situation of migrants with respect to healthcare, ideas were proposed to bring health teams closer to the community: “I think that, maybe, the clinic could bring together the immigrants from my country and […] to improve care” (Female interviewee 1, personal communication, November 2014), “it would be like legalizing or helping foreigners more, so we have social secrurity, regardless of whether we have an employment contract” (Female interviewee 2, personal communication October 2014).

It should be mentioned that there are several health systems in Chile, and these vary depending on individuals’ economic condition. The public system serves most of the population, including the most vulnerable sectors. In this sense, the healthcare provided to migrants is shared with underprivileged locals due to their economic and social conditions. As a consequence, the perceived problems in public healthcare, and specifically at the primary level, are shared by Chileans and immigrants, and the frequency of healthcare problems reported by immgrants in the 2013 CASEN survey is very similar to figures mentioned by Chilean users of the system ( Ministry of Social Development, 2003 ). Considering that the health system is a fundamental step in social integration ( Concha, 2015 ) and that the primary level is a model for bringing health services to communities, any public policy or strategy to improve and enhance primary healthcare will benefit both Chilean citizens and migrants.

Lastly, from a general and abstract perspective, it is worth analyzing aspects associated with public policy. Migration and health policies, including the right to health, fall under this category. These three aspects are closely related, given that the Chilean constitution stipulates that citizens have the right to choose their system of healthcare (public or private insurance) provided they hold an employment contract. In this sense, both Chilean and foreign workers with a contract (and their legal dependents) are entitled to healthcare and insurance under similar conditions, depending on income. This means, then, that documented migrants with an employment contract enjoy the same access to health and healthcare as Chileans in similar conditions. Citizens without an employment contract, on the other hand, fall under the category of indigentes (destitute people) and must use the public health system, thus losing the right to choose. As for migrants, participants’ accounts reveal an indeterminate number of undocumented migrants in a vulnerable and degenerate socioeconomic situation, who are unfamiliar with the healthcare system, making it difficult to use the support available effectively: “I live with […] women from foreign countries, we don’t have social security […] the money we earn is just enough for the rent, nothing else” (Female interviewee 2, personal communication, October 2014). The situation described supports the claims made by Cabieses, Pickett, and Tunstall (2012) in the article “What are the living conditions and health status of those who don’t report their migration status?” From a structural perspective, the differential in social and health vulnerability may therefore result from irregular migratory and work status, which prevents them from being identified by the system, marginalizing them for the purposes of healthcare. Nonetheless, a revision of the regulations provides a way out of this impasse through Decree No. 67 by the Ministry of Health of Chile (2015a) , by which irregular immigrants, or those without a visa or documents, become beneficiaries of Fonasa. However, many are unaware of this possibility, so one relevant proposal would be to disseminate this information on available health benefits. In this sense, the Ministry of Health of Chile has implemented pilot programs for migrant healthcare in three cities in the north of the country and two communes in the capital, Santiago de Chile ( Ministry of Health of Chile, 2015b ). However, such efforts seem inadequate in places where migrants are already arriving, as the system is ill-prepared to offer healthcare in line with the specific needs of this population group, as is the case in the city of Coquimbo.

It should be mentioned that the research has some limitations. Firstly, it is exploratory and nested within a larger study, limiting methodological flexibility. Similarly, the exploratory nature of the study limited the development of theories that may provide a more in-depth explanation of immigrants’ social and health vulnerability. However, insight was gained into the factors that influence this vulnerability from the perspectives used to analyze this situation (shown in Table 3). Although the study was conducted across a commune, through its qualitative and explorative nature, it seeks to draw on participant discourse to understand migrants’ situation rather than generalize it. It is also worth considering that health vulnerability associated with public policy and the organization of the system are a problem at a national level in Chile. As far as healthcare and associated resources are concerned, the situation in the commune under study is similar to that found in other cities or urban communes in the country, where primary-level healthcare is also managed by the municipality, and governed by the same funding system and regulations ( Ministry of Health of Chile, 2012 ; Subsecretariat of Health Aid Networks [Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales], 2015 ).

Conclusions

In response to the questions “What makes immigrants more health vulnerable than Chilean citizens?” and “What does this study contribute to this knowledge?”, it can be said that if working conditions were aligned, migrants’ vulnerability would be negatively affected in terms of their mental health, although this could be mitigated by support networks and their capacity for adaptation and cultural and social integration. Their greater social and health vulnerability, with respect to citizens, may be determined, to an extent, by whether local strategies geared toward migrant healthcare are deployed in the geographical area of residence, as policies and strategies are only being developed in certain parts of the country.

The challenges encountered in developing the foundation and analysis of this case study reveal the need to step up research in the health field to understand the health situation of the Latin American immigrant population and promote the development of international and national policies and local strategies to integrate this social group effectively into the host society.

REFERENCES

Acosta González, E. (2013). Mujeres migrantes cuidadoras en flujos migratorios sur-sur y sur-norte: expectativas, experiencias y valoraciones. Polis, Revista Latinoamericana, 12(35), 35-62. Recuperado de https://journals.openedition.org/polis/9247 [ Links ]

Amezcua, M. y Gálvez Toro, A. (2002). Los modos de análisis en investigación cualitativa en salud: perspectiva crítica y reflexiones en voz alta. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 76 (5), 423-436. http://doi.org/10.1590/S1135-57272002000500005 [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (2008). Globalisation and acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32 (4), 328-336. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.04.001 [ Links ]

Burgos, Monica y Parvic, T. (2010). Atención en salud para migrantes: un desafío ético. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 64 (3), 587-591. http://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672011000300025 [ Links ]

Burman, E. (2016). Lessons in the psychology of learning and love. Psicoperspectivas. Indiviuo y sociedad , 15 (1), 17-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol15-Issue1-fulltext-666 [ Links ]

Cabieses, B., Pickett, K. E. y Tunstall, H. (2012). What are the living conditions and health status of those who don’t report their migration status? a population-based study in Chile. BMC Public Health, 12 (1), 1013. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1013 [ Links ]

Cabieses, B., Tunstall, H. y Pickett, K. (2015). Understanding the Socioeconomic Status of International Immigrants in Chile Through Hierarchical Cluster Analysis: a Population-Based study. International Migration, 53 (2), 303-320. http://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12077 [ Links ]

Cabieses, B., Tunstall, H., Pickett, K. E. y Gideon, J. (2012). Understanding differences in access and use of healthcare between international immigrants to Chile and the Chilean-born: a repeated cross-sectional population-based study in Chile. International Journal for Equity in Health , 11 (1), 68. http://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-68 [ Links ]

Cano, M. V., Contrucci, M. y Pizarro, J. (2009). Conocer para legislar y hacer política: los desafíos de Chile ante un nuevo escenario migratorio. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Naciones Unidas/CELADE-CEPAL. [ Links ]

Castañeda, H. et al. (2013). Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36 (1), 1-18. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419 [ Links ]

Concha, N. L. (2015). Poder, contrapoder y relaciones de complicidad entre inmigrantes sudamericanos y funcionarios del sistema público de salud chileno. Si Somos Americanos. Revista de Estudios Fronterizos, XV(2), 15-40. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0719-09482015000200002 [ Links ]

Elizalde, A., Thayer, L. y Córdova, G. (2013). Migraciones sur-sur: paradojas globales y promesas locales. Polis, Revista Latinoamericana, 12 (35), 7-13. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682013000200001 [ Links ]

Gomes Campo, C. J. y Ribeiro Turato, E. (2009). Análisis de contenido en investigaciones que utilizan la metodología clínico-cualitativa: aplicación y perspectivas. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 17(2), 259-264. [ Links ]

Jaacks, L. M. et al. (2012). Migration Status in Relation to Clinical Characteristics and Barriers to Care Among Youth with Diabetes in the US. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health , 14 (6), 949-958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9617-3 [ Links ]

Jurado, D. et al. (2017). Factores asociados a malestar psicológico o trastornos mentales comunes en poblaciones migrantes a lo largo del mundo. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental, 10 (1), 45-58. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.04.004 [ Links ]

Lund, C. (2014). Of What is This a Case?: Analytical Movements in Qualitative Social Science Research. Human Organization, 73 (3), 224-234. http://doi.org/10.17730/humo.73.3.e35q482014x033l4 [ Links ]

Marroni, M. da G. (2016). Escenarios migratorios y globalización en América Latina: Una mirada al inicio del siglo XXI. Papeles de Trabajo, 32, 126-142. [ Links ]

Miles, M., Huberman, A. y Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (3.a ed.). Phoenix, AZ: Arizona State University/SAGE. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social. (2013). Encuesta de Caracterización Socioeconómica Nacional . Santiago de Chile, Chile: Autor. Recuperado de http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/documentos/Casen2013_Pueblos_Indigenas_13mar15_publicacion.pdf [ Links ]

Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile. (2011). Requisitos para solicitar nacionalidad . Santiago de Chile, Chile: Departamento de Extranjería, autor. Recuperado de http://www.extranjeria.gob.cl/media/2018/02/Requisitos-Para-Solicitar-La-Nacionalidad-Chilena-Por-Nacionalización.pdf [ Links ]

Ministerio de Salud de Chile. (2012). Marco regulatorio del financiamiento de la salud municipal. Decreto per cápita, cálculo Fonasa y ley GES. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Autor. Recuperado de https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=30745 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Salud de Chile. (2015a). Decreto Supremo 67, año 2015. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Autor, Gobierno de Chile. Recuperado de https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1088253 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Salud de Chile. (2015b). Salud del Inmigrante . Santiago de Chile, Chile: Autor. Recuperado de http://www.minsal.cl/salud-del-inmigrante/ [ Links ]

Ministerio del Interior. (2016). Migración en Chile 2005-2014 . Santiago de Chile, Chile: Autor. Recuperado de http://www.extranjeria.gob.cl/media/2016/06/Anuario.pdf [ Links ]

Mora, C. (2008). Globalización, género y migraciones. Polis, 7(20), 285-297. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682008000100015 [ Links ]

Ojeda, V. D. et al. (2009). Associations between migrant status and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85 (6), 420-6. http://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2008.032979 [ Links ]

Organización de Cooperación y Desarrollo Económico. (2015). OCDE 360: Chile 2015 ¿En qué situación está Chile comparativamente? Chile: Autor. Recuperado de http://www.oecd360.org/oecd360/pdf/domain21media1988310488-2sr2soko0d.pdf [ Links ]

Stefoni, C., Bonhomme, M., Hurtado, U. A. y Santiago, C. (2014). Una vida en Chile y seguir siendo extranjeros. Si Somos Americanos. Revista de Estudios Fronterizos, XIV(2), 81-101. [ Links ]

Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales. (2015). Eje gestión de recursos financieros en atención primaria . Santiago de Chile, Chile: Autor. Recuperado de http://web.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/4_GESTION-RECURSOS-FINANCIEROS-APS.pdf [ Links ]

Urzúa, A., Heredia, O. y Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2016). Salud mental y estrés por aculturación en inmigrantes sudamericanos en el norte de Chile. Revista Médica de Chile, 144 (5), 563-570. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872016000500002 [ Links ]

Urzúa, A., Vega, M., Jara, A., Trujillo, S. y Muñoz, R. (2015). Calidad de vida percibida en inmigrantes sudamericanos en el norte de Chile. Terapia Psicológica, 33(2), 139-156. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082015000200008 [ Links ]

Vásquez-De Kartzow, R. (2009). Impacto de las migraciones en Chile. Nuevos retos para el pediatra. ¿Estamos preparados? Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 80 (2), 161-167. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0370-41062009000200009 [ Links ]

Vásquez-De Kartzow, R., Castillo-Durán, C. y Lera, L. (2015). Migraciones en países de América Latina. Características de la población pediátrica. Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 86 (5), 325-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rchipe.2015.07.007 [ Links ]

Received: March 16, 2017; Accepted: August 10, 2017

texto en

texto en