Introduction

In the last two decades, Spain, a traditional migrant sending country, has become one of the top nations that receive migrants in Europe. This, together with the continuing effects of the 2008 financial crisis, has generated not only academic interest but social and political debate on whether the migrants will stay or eventually return home. This concern has been materialized through the recent inclusion (from 2011 onward) of return issues in public surveys related to immigration, such as the Regional Immigration Survey (ERI in Spanish) or the Migration Barometer of Madrid Region. Regional migration authorities are very interested in knowing the underlying variables on return intentions in order to refine their migration policy design process. Moreover, as migration to Spain has been mainly driven by economic factors, a better knowledge of the relationship between return intentions and labor market circumstances may be paramount for this purpose.

The thought that return migration would dramatically increase in Spain was supported by the higher immigrant unemployment rate (around 33 % versus 22 % for natives, according to the Active Population Survey, fourth quarter of 2014) in conjunction with the instability of immigrant jobs (many of them in the underground economy) and weaker family networks. Nevertheless, emigration flows have declined more slowly than expected.

According to the Spanish Statistical Office, in mid-2014 there were 4 538 503 foreign citizens in Spain, 9.8 percent of the total resident population in the country. There also were 1 830 123 people who had already obtained Spanish nationality. Consequently, it could be argued that 13.7 percent of residents in Spain are immigrants.

Regarding the migration flow, the Estimate of the Current Population shows 1 696 153 migratory departures corresponding to people born abroad between 2008 and 2012; 62 493 of these involved naturalized foreigners. Although there has been a slight, gradual increase from 2008, the figure has remained relatively stable at approximately 350 000 such departures per year.

In this paper, we try to analyze the underlying variables of return intention of migrants, segmented by their legal status, in the Autonomous Community of Madrid. The microdata source is the ERI 2011-2012 of the Madrid Region. This survey is issued annually by the immigration authorities of the Madrid Autonomous Community. Its main purpose is to collect relevant information about the immigrant population settled in the region.

First, we review existing literature on both return migration and return intentions, and extract the main set of variables used in this work. Literature on the return of irregular and regular migrants is also reviewed, as well as immigrant return intentions in the Spanish context. The second section of this paper deals with research questions, variables, and methodological issues. In the final section, we offer a set of conclusions, a profile of the potential returnees, and some policy implications.

Previous Research

Return Migration and Return Intentions

Traditionally, migration scholars have taken for granted that migration is a unidirectional process; as a consequence, very little attention has been paid to return migration. Indeed, return migration studies do not commence until the early 1960s, when Sjaastad (1962) , Appleyard (1962) , and subsequent empirical works ( Bovenkerk, 1974 ; Gmelch, 1983 ; King, 1986 ) show how emigration often goes together with return migration. Conceptualizing return migration is a complex undertaking because return takes place in different forms and under different conditions. In fact, underlying return variables have been used in opposite ways by scholars with different theoretical approaches to international migration ( Cassarino, 2004 ).

Return migration decisions are always preceded by the intention to return. Return and return intentions show both sides of every migration movement. In the migration literature, “intention” to move means a “willingness” to move ( Anh, Jimeno, & García, 2002 ), a voluntary action based upon free choice ( Moran-Taylor & Menjívar, 2005 ), although this does not negate the possibility that external factors influence the decision ( Senyürekli & Menjívar, 2012 ).

Bovenkerk (1974) was a pioneer in conceptualizing migrants’ return intentions: He matched migration duration intention with actual migration movement, and subsequently provided four categories of migrants (permanent or temporary migration and with or without return). Russell King (2000) established four types of return migration (occasional, seasonal, temporary, and permanent), analyzing the intentions of returnees and the course of the return process. Cassarino’s approach (2004) deals with returnees’ preparedness, that is, return only takes place once the migrant has gathered sufficient resources and information about the situation in the country of origin.

What is the use of studying the intentions to return? It has been argued that intentions have explanatory power on subsequent behavior, for both return and return intentions ( Baruch, Budhwar, & Kathri, 2007, Güngör & Tansel, 2011 ). Nevertheless, this has been questioned empirically in panel data analysis: Constant and Massey (2003) and Baalen and Müller (2008) showed that of those who declared their intention to return, only a minimum share ended up going back to their countries of origin. Moreover, Constant and Massey (2003) in their 14-year longitudinal study (using immigrants’ life-cycle events) conclude that for the average immigrant, the probability of return is very low, close to zero.

Moreover, there is abundant literature on the so-called myth of return ( Bolognani, 2007 ; Klimt, 2000 ; Hiller, 2009 ; Sinatti, 2011 ), where the potential returnees repeatedly express their (finally unfulfilled) intentions and expectations to go back to their home countries. In fact, intentions to return can change over time ( Dustmann, 1996 , 2001 ) or with changing life-cycle circumstances ( Güngör & Tansel, 2005 ).

Some Explanatory Factors of Return Intentions

Regarding the determinants of (and their effect on) return intentions, most scholars report contradictory findings while using the same variables. We have grouped the available variables in our data source that motivate return intentions into four categories:

Personal features , such as gender, nationality/ethnic group, and time-related variables (age or years since migration).

Social ties , such as family connections or home ownership in the receiving country

Economic variables , such as participation in the host country’s labor market, having access to social benefits, and remittance behavior.

Contextual variables , such as the economic, social, and political setting in the countries of origin and destination, return and immigration legislation, and so forth.

Some of these sets of factors produce controversial results, as in the case of personal features or economic variables.

With respect to individual characteristics, several authors find explanatory power in gender ( Roman & Goschin, 2012 ), while others don’t ( Waldorf, 1995 ). Nationality becomes important when explaining return intentions in Alberts and Hazen (2005) or de Coulon and Wolff (2010) . Length of stay appears to be negatively linked to the return decision, because of greater integration in host societies ( de Haas & Fokkema, 2011 ). Regarding age, Klinthäll (2006) and Larramona (2013) state that younger and older cohorts have a higher willingness to return. Yendaw (2013) finds that migrants’ reasons for returning (family issues, political restrictions in receiving countries, investments at home) vary with the respondents’ age. In fact, for some authors ( Predosanu, Zamfir, Militaru, Mocanu, & Vasile, 2011 ; Güngör & Tansel, 2011 ), older age groups are more likely to return soon. Length of stay appears to be negatively linked to the return decision because of the greater integration this produces in host societies ( de Haas & Fokkema, 2011 ).

Moving on to economic variables, there is no agreement on the influence on return intentions caused by success, or the lack thereof, in the labor market. Some works highlight that better salaries and higher incomes delay return decisions ( Makina, 2012 ; Paile & Fatoki, 2014 ), while others say that an individual’s poor performance in the host labor market (not being able to attain the targeted income) is a reason for prolonging one’s stay in the receiving country. Regarding social benefits, Reyes (1997) finds that those with higher levels of integration are less interested in subsidy settlements. Finally, in the area of remittance behavior, de Haas and Fokkema (2011) find a positive relationship between sending remittances for individual use and return intentions.

A broader consensus seems to have been reached for social tie factors and contextual variables: In the case of social variables, there is a negative relationship between return intentions and having family ties—a partner and children—in the host country ( Khoo, 2003 ; Dustmann, 2008 ; Haug, 2008 ; Pungas, Toomet, Tammaru, & Anniste, 2012 ). Moreover, owning either a home or home satisfaction in the host country ( Waldorf, 1995 ) has positive effects on the return decision.

Concerning the contextual variables, a favorable economic, social, and political setting in the destination country has negative effects on return decisions ( Alberts & Hazen, 2005 ; Stocchiero, 2008 ), while a favorable economic, social, and political setting in the country of origin has positive effects on return decisions ( Khoo, McDonald, & Hugo, 2009 ; Makina, 2012 ).

Subjects of Study: Regular Versus Irregular Migrants

When discussing immigrants’ legal status and return intentions, some authors ( Constant & Massey, 2002 ; Senyürekli & Menjívar, 2012 ) say that administrative status prevents migrants from leaving the country, while others say that, under certain circumstances, irregular migrants tend to return sooner than their legal peers. Reyes (1997) finds that undocumented immigrants are much more likely to return than documented ones, as only those who are more educated and have stronger positions in the labor market enjoy a better life in the destination country. Coniglio, de Arcangelis, and Serlenga (2009) find that highly skilled clandestine migrants are more likely to return home than migrants with low or no skills when illegality reduces the rate of return of individual capabilities (i.e., skills and human capital) in the country of destination. Given this, the opportunity cost of returning to the country of origin should be substantially lower for the skilled individuals than for the unskilled.

Van Meeteren, Engbersen, and van San (2009) and van Meeteren (2012a, 2012b) establish the likelihood of return for irregular migrants who are attending to their aspirations. Hence, there are three types of migrants. First, there are those with investment aspirations , who aim to work and make money with which to return to their country of origin.

Second, there are immigrants with settlement aspirations, where the stay itself is the objective. Third, there are irregular migrants with legalization aspirations who want to acquire legal residence status. For them, leading a better life is inextricably bound up with legal status and they do not have the intention to return.

Indeed, irregular migrants experience various forms of capital attainment related to their aspirations. Investment migrants try to acquire cultural capital (job competencies) and social capital under the form of transnational social networks. They also are frequently involved in economic activities, while not very committed to political issues ( van Meeteren, 2012a , 2012b ). This intentionality could explain the driver for irregular female domestic workers ( Kontos, 2013 ) who initially see this work as a temporary measure for providing funds for their family back home.

Immigrant Return Intentions in the Spanish Context

As far as the Spanish case is concerned, in the last few years, and as a consequence of the global economic crisis, germinal research on return migration is starting to emerge, focused on both contextual/ labor market factors and personal/family factors. Regarding return intentions, no research has been conducted, so far.

Family factors (and the subsequent sociocultural integration) appear to have a high explanatory power in return migration intentions ( de Haas, Fokkema, & Fihri, 2015 ). According to Bastia (2011) , return decisions are generally taken based on personal responsibilities, separation from children, or ill health. Moreover, Pusti (2013) points out how connections with family living in Spain, together with the better quality of life available for the family, encourage decisions to stay.

Contextual variables together with labor market factors are analyzed by Pajares (2009) , López de Lera (2010) , and Larramona (2013) . These scholars say that a poor situation in the country of origin is negatively related to return migration: This would explain why Asians, Africans, and Latin Americans would be less likely to return home. In addition, the restrictive political measures implemented by the Spanish government, such as the voluntary return plan that offered return bonuses to non-European Union foreigners who agreed to leave for at least three years ( Beet & Willekens, 2009 ; Bastia, 2011 ), made migrants stay because of the impossibility of returning to Spain in the near future.

Irregularity turns out to be significant regarding return intentions. De Arce and Mahía (2012) say the probability of return is two times higher when an irregular situation is maintained when it comes to personal documents. Furthermore, Mahía and Anda (2015) observe that although the worsening of labor and living conditions generated by the economic downturn does not drive return, the loss or weakening of legal status appears as a prevailing return driver.

Questions, Data, and Methods

Research Questions

The information available in the survey together with the determinants of return intentions proposed in the literature allowed us to formulate our research questions. We have created the predictors of return intentions for both legal and illegal immigrants using the categories identified in the literature review and those available in the ERI.

The ERI does not provide explicit information on contextual variables related to the sending or the receiving country. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, a favorable economic social and political setting in the destination country has effects on return decisions. Thus, the study takes into account when migrants arrive, in this case considering the year of arrival before or after the onset of the economic downturn.

We assume that there are significant behavior differences between the two groups (regular and irregular migrants) as they face different circumstances. In fact, personal characteristics of both populations are different: Irregulars are usually younger and occupy significant shares in determined labor market niches (such as domestic service), so their working conditions are much more precarious. In addition, irregulars are not usually able to reunite with their families.

Thus, two main research questions underpin our analysis: 1) Do immigrants’ return intentions vary according to their legal status (regular or irregular)? 2) What are the main explanatory variables of return intention for both legal and illegal immigrants?

The Data: The ERI

The microdata source we used for the empirical analysis comes from the Madrid Regional Immigration Survey (ERI in Spanish) 20112012. The ERI, issued annually by the immigration authorities of Madrid Autonomous Community, collects relevant information about the immigrant population settled in the region (the confidentiality of survey respondents was respected). Although the ERI has been conducted yearly since 2008, microdata has not been made publicly available. Accordingly, we thank and gratefully acknowledge the support of those who allowed us to use the data.

The sample, originally composed of 2 992 interviews conducted between December 2011 and January 2012, is random and segmented by nationality or original geographical location (Romania, Ecuador, Morocco, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, China, Dominican Republic, Paraguay, Bulgaria, and Sub-Saharan Africa). The survey is split into five parts, namely: 1) Personal and family features, 2) Legal status, 3) Housing conditions, 4) Employment status, and 5) Social benefits enjoyed by the respondent.

This survey has the following limitations:

The survey analyzes return intention, which is an ambiguous concept and varies with time as stated in the theoretical review.

The academic background and professional experience of the individual is not included. This information is key for return intentions analysis.

It provides details on the date of arrival, but it does not give information on the return dates of interviewees.

The survey does not deal with migration motives.

Respondents are not asked about their social and political economic perception or origin or host country.

The sample is split into three categories in terms of legal status: those who have an identity card, those with a residence permit or a student visa, and the irregulars (those who do not possess any documents). Table 1 disaggregates the three categories by nationality.

It can be observed how the most weighted nationalities among those who have residence permits are very heterogeneous, but not so in the two remaining cases. This fact made us obtain no significant coefficients or coefficients with very different signs than expected, in preliminary econometric analysis.

Furthermore, the main concern of Madrid migration authorities was to refine return policies on the basis of the immigrant labor market. In this regard, residence permits are not necessarily linked to labor permits. Conversely, the extreme categories, naturalized residents (theoretically behaving as Spaniards, with full freedom of movement and access to employment) and irregular residents (tied to the underground labor market with no freedom of movement at all) became of greater interest.

Thus, we decided to remove the category of residence permit from the sample, which wound up being composed of 563 individuals, broken down into those with identity cards and irregulars. A binomial logit model was applied to each category, as described in the next section.

Proposed Methodology: The Binomial Logit Model

The logistic regression model is one of the most frequently used probabilistic statistical classification models to study the causes that account for the differences between two or more groups. Binomial (or binary) logistic regression is a form of regression used when the dependent variable is a dichotomy and the independents (or covariates) are of any type. The binomial logit regression assumes there is no need for the explanatory variables to be statistically independent from each other ( Hilbe, 2009 ). Nevertheless, measures of association and correlation have been carried out, indicating a low dependence among predictor variables.

A binomial logit model (henceforth BLM) has been used to predict a dependent variable with two categories, based on continuous and categorical independent variables, to determine the explained percentage of variance. Thus, the relative importance of independent variables is ranked, and the impact of covariate control variables becomes understandable. A pseudo R2 statistic is available to summarize the strength of the relationship.

Authors such as Makina (2012) , Pungas et al. (2012) , Roman and Goschin (2012) , Khoo et al. (2009) , Khoo (2003) , and Waldorf (1995) use the BLM to explain the return intentions and the outcomes are methodologically satisfactory.

Dependent Variable

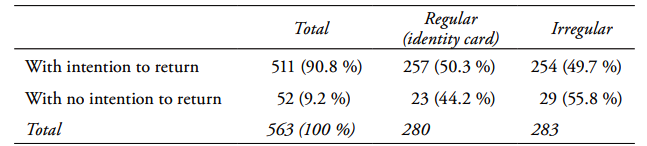

The dependent variable, which is now a dichotomous one ( Table 2 ), was initially composed of six categories: three categories of With intention to Return ( Soon , At some point in a few years , or At retirement ), With no intention to return , Moving to other country , and Doesn’t know .

The cases under the categories Moving to another country and Doesn’t know account for 33.6 percent of valid cases and were removed because they did not show a clear return intention for the purposes of this article. Hence, we decided to merge the return-related variables ( Return soon, At some point in a few years , or At retirement ), because no statistically significant differences were found in the effects of social, personal, contextual, and economic factors of the three estimated models.

Then, we segmented the sample attending to the legal status, as pointed out in the beginning of this section. Therefore, two models have been estimated: one for the category Regular and another for Irregular .

Groups of Independent Variables

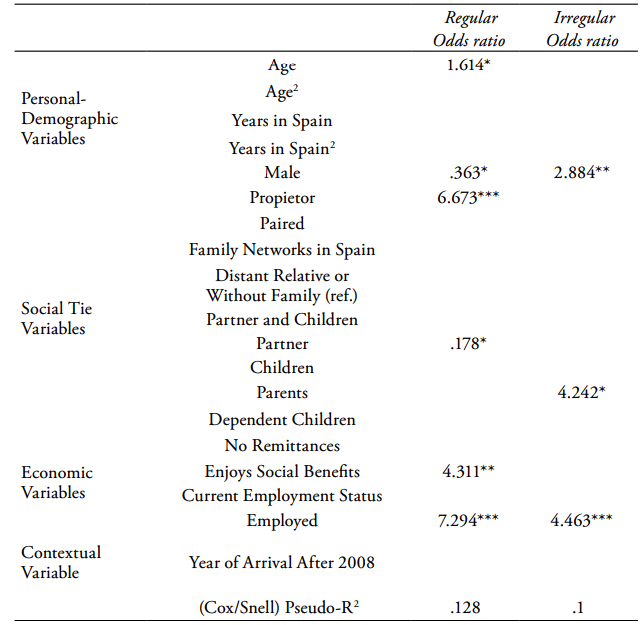

The proposed BLM relies on several predictors of return intention. Such predictors have been selected and grouped according to the categories identified through our literature review process, and those available in the ERI. Hence, four clusters of variables were selected, as shown in Table 3 . Nationality, which had been used to break the original sample, is not included in the BLM because of its heterogeneity when considering the two categories related to legal status (as shown above in Table 1 ).

Results

Table 4 shows the estimated results of the odds to return intention for regular and irregular immigrants in the Madrid region. As for the immigrants with legal status . The propensity of return intention is mainly driven by economic factors .

Regarding personal-demographic variables, the results clearly demonstrate that men are less likely to express an intention to return than women (64 % lower) are. The better position of men in the current Spanish labor market when they have a legal status could support this assertion. According to life-cycle models, increasing age has also a positive impact on return probability.

In relation to economic variables, the results reveal that the probability of intention to return is 7.2 times higher for those who are employed than for those who are unemployed. The employed are more prone to go back to their countries of origin, which means that they may have fulfilled their objectives and expectations, although they have made progress in terms of economic integration. The direction of the effect appears to be in line with the hypothesis stated in many life-cycle models that show return as a sign of completion of the migratory cycle, once there is enough money to accomplish preestablished objectives.

Furthermore, return intentions become 4.3 times higher for those who receive social benefits with respect to those who are not entitled to such benefits. The underlying reason may be that these respondents have succeeded in the labor market and have reached social positions (that allow access to social benefits) close to those of the native workers.

In addition, social ties (those variables such as owning a house or enjoying social benefits that indicate a successful trajectory in Spanish society) are closely connected to return intentions. In fact, as demonstrated when analyzing the economic variables, only those wealthy enough could afford to consider going back home. Therefore, if the migrant is a homeowner, the probability of return intention is 6.6 times higher than in the case of non-owners. Having a house might mean that immigrants have attained sufficient economic independence to return home and thus have accomplished their migratory project. Moreover, that might mean that the property could be sold in order to buy a house in their country of origin.

Finally, as stated repeatedly in the literature review, when migrants have their partners in Spain, the odds of return intention are much (almost 82 %) lower.

As far as immigrants with irregular status are concerned. The propensity of return intention is, as stated for the regulars, more strongly driven by economic factors , that is, the influence of current employment status has a significant positive impact on the odds of return intention, becoming 4.4 times higher for the employed than for the unemployed. This fact would be in line with those research findings that show how irregular immigrants, especially the ones with investment aspirations, tend to use their positions in the labor market to save, and rapidly accomplish their return objectives.

Regarding personal-demographic features, gender also has a stronger impact on return probability, which meant that the odds for men were 2.8 times higher than the odds for women. This is consistent with the peculiarities of Spanish labor market. On the one hand, the situation of women in the labor market (mainly domestic service) allows males an earlier return than females. On the other hand, irregular immigrant male workers often are not willing to work in jobs for which they are overqualified where their human capital is wasted.

In relation to social tie variables, the probability of intention of return when migrants have their parents in Spain is 4.2 times higher than for those who live without relatives or families. As pointed out above, research connects young age to a higher propensity to return.

This could be closely linked to the myth of return, especially in those cases of young irregular migrants with investment aspirations.

In any of the two groups (regular or irregular status), the contextual variable turned out to be significant. This is in line with previous research findings and confirms the importance of opportunity structure in sending countries. Their human development and macroeconomic indicators have fallen much more than Spanish ones on a comparative basis. This is why the Spanish economic downturn has not acted so strongly as a push factor.

Discussion

The BLM model seems to answer our research questions. That is, there are significant behavioral differences between the two groups as far as return intentions are concerned, with respect to personal features, social ties, and labor market performance; the adverse economic environment is not a determinant for return intentions.

The explanation of these differences relies on the following:

-

The split immigrant labor market: segmentation by gender

One way of looking at jobs within the Spanish immigrant labor market is to see them as either feminine (mainly domestic service by those involved in illegal migration) or masculine (semi-skilled jobs in construction, agriculture, services, and commerce). Male jobs allow migrants to reach better positions and more rapidly fulfill their objectives. On the contrary, many women are bound to domestic service, a low salary niche (whether legal or illegal) that slows down goal achievement. This fact would explain why regular women prefer to return while their male peers can afford stay.

As for irregular migrants, males have a higher propensity to return home than females, either because they have no work, or because they are employed in low-skilled jobs and do not want to work in jobs they are overqualified for. On the contrary, women in domestic service seem to have investment aspirations and are willing to remain in Spain until their objectives are fulfilled.

-

Better living conditions are very much linked with successful labor market performance

Only those with good salaries would have been able to own a house or to obtain social benefits (other than the universal access to health care). This issue is clearly illustrated in our model, where those regular immigrants who are better off (in terms of home ownership or welfare provision access) are more likely to think about returning.

These variables (owning a home and enjoying social benefits) are not significant for irregulars. Nonetheless, in this group, a better labor performance increases the probability to intend to return.

-

The adverse environment

In 2007, Spain began to experience a severe economic downturn that still seems to be occurring. Hence, when analyzing return intentions, one could think that the (worsening) contextual variables could become statistically significant. Nevertheless, this did not happen, neither for regulars nor for irregulars. The explanation could be found in the nationalities of the potential returnees. Insofar as the economic setback is global, the sending countries are experiencing even tougher times. This fact undoubtedly prevents immigrants from going back home.

-

Age, return intentions, and legal migrants

When analyzing return intentions, age shows opposite effects in both groups. Illegal migration is mainly composed of young people (many of them living with their parents) with shortterm goals, who might be fed by the myth of return. However, in the case of legal migrants, the marginal propensity to return appears to increase with age: the older the immigrants are, the better they are situated and so, the closer they are to reaching their goals.

To conclude, we can state that the profile of the legal migrant who intends to return home is a woman of a certain age, who is employed, is a home owner, is entitled to social benefits, and does not maintain strong family ties in Spain. By contrast, irregulars who are the most willing to return are males, with parents in Spain, and with jobs (presumably underemployed).

It must be pointed out that intentions to return might not be always a reliable measure of return as they can change with time or with changing life-cycle circumstances.

Despite the limitation mentioned above, some lessons can be learned from this study that could allow the authorities to improve migration policy design:

By linking return policies to successful development in the labor market, the return would, to a greater extent, become a personal decision and not the only choice after a failed migration project. In fact, the Domestic Service Amendment Act in Spain marked a milestone in the immigrant labor market. In the medium term, this will allow domestic workers to enjoy a more stable situation and therefore accomplish their migratory project.

Other possible measures are those targeted at promoting immigrants’ long-term savings and reinvestment in sending countries; to foster the transfer of skills and knowledge acquired during migration; and to encourage circularity.

Anyhow, these policies can hardly be implemented without the awareness of both sending and receiving countries. A possible starting point through the development of joint policy initiatives would be to improve information flows and bilateral agreements between countries.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)