Introduction

From 2004 to 2010, Arizona's administrations and Congresses implemented a far-reaching series of policies against undocumented immigrants. Among them was the passage of more than 40 laws that sought results ranging from excluding immigrants from enjoying certain social and public services to sanctioning them with the aim of their "self-deporting," and in addition creating disincentives for the arrival of new immigrants without the required documentation. This article's aim is to explain and analyze the reasons for the existence and restrictive sense of the harshest of all these laws, Arizona's SB 1070 (Arizona State Legislature, 2010). Doing a study of a single state law has two big advantages: being able to capture the complexity of a phenomenon characterized by interactive effects of structural and agency-based variables, and the presence of multiple strategic actors pursuing unknown goals (Lodola, 2009).

In contrast to other research focusing on political leaders or the electorate to explain the existence of a particular anti-immigrant policy,2 in this article, I consider it necessary to look at both to fully explain how and why SB 1070 was passed. Most citizens do not usually have direct influence on the passage of bills and the approval of laws on undocumented immigrants. However, they do have indirect influence that allows them to exercise power over people in public positions, using their vote for electing their representatives, their ability to hold referendums to revoke laws, etc.3

To achieve the objective, I use an ad hoc combination of theories and theoretical approaches encompassing the reasons for the existence of open or restrictive immigration policies.4 It must be kept in mind that SB 1070 became law in a sub-national territory and that its articles do not apply strictly speaking to immigration, but to undocumented immigrants.5

For clarity of presentation, the article is divided into three parts. The first succinctly explains the historical-political context in which SB 1070 is immersed; the second describes the economic, cultural, and security factors that generated its voter support in Arizona; and the third looks at the different motivations that led Republican political leaders to pass it.

Finally, the main conclusion of my analysis is that the Arizona law is the result of an attempt to satisfy electoral interests and to promote an anti-immigrant agenda on a state and national level with broad voter support. None of this disregards other factors that intervened, for example, the support it received from anti-immigrant groups.

Brief Historical-Political Context of SB 1070

To understand the passage of any law, we have to know about the historical-political context in which it was approved. This section of the article looks at the most important issues in the background of the passage of SB 1070, both nationally and on a state level. There are three crosscutting themes to this: border control policies, the failure of immigration reform, and the rise of anti-immigrant policies in the United States, particularly in Arizona.

The configuration of a new immigration system based on the 1965 legislation created a new migratory pattern in which undocumented immigrants began to predominate. The figures for undocumented immigrants in 1986 came to 1.6 million, according to Massey and Singer (1995, quoted in Tuirán and Ávila, 2010). This gave rise to an important "problem" to be solved: What should be done about immigrants without papers?

In the face of this, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) attempted unsuccessfully to reverse the situation: the number of undocumented immigrants in 1990 was 8.6 million. IRCA was made up of two amnesty programs, one for special agricultural workers (SAW) and another for legally authorized workers (LAW), sanctions against employers who hired persons without documents, and funds for beefing up border control.

Five years later, in the context of the security paradigm, border control became the most important aim of U.S. immigration policy. In 1993, the Clinton administration decided to take the reins of border control, increasing the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) budget and the number of agents. From that time on, a strategy of innumerable operations more or less randomly came into effect: Hold-the-Line in El Paso, Texas (1993); Operation Gatekeeper in the San Diego, California area (1994); Operation Safeguard in Arizona (1995); Rio Grande in Texas (1997); and many others up until today.6 The most terrible consequence of these measures is that it pushed immigrants toward crossings that endangered their lives more, leading to the deaths of more than 5,000 immigrants (Bustamante, 2002; Anguiano Téllez, 2009). In addition, undocumented crossings shifted toward the Arizona/ Sonora border because of these operations, and that area became the main crossing place. Cornelius (2001) used the number of detentions in Department of Homeland Security data to illustrate this; for their part, Anguiano Téllez and Trejo Peña (2007) used the Survey on Northern Border Migration (Emif-Norte) to show in detail the changes in these routes. In addition, Arizona became an important place for settlement: "Immigrant workers, both legal and illegal, who might have only passed through the state in the mid-1990s on their way to jobs in other regions now had reasons to stay: a plentiful supply of jobs, particularly in construction and associated industries" (Singer, 2010).

In 1994, simultaneously with the coming into effect of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in Mexico, the United States, and Canada, California voters approved Proposition 187, which denied undocumented immigrants social services, medical care, and public education. Two years later, "the echoes of Proposition 187 were heard in Washington, D.C." (Varsanyi, 2010:2), and the U.S. Congress passed a series of laws that, in addition to other aims, reflected the issues addressed in the proposition. Among those laws were the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. IIRIRA Section 287(g), included as stipulation 133, would create the possibility for agreements between U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and local governments for local and state police departments to enforce federal immigration laws.

A decade later, the "problem" of undocumented immigrants continued unabated, and the federal government was continuing to sort through different ways to solve it. Between 2004 and 2007, several proposals for reform were presented and discussed in Congress, but none came to fruition. These projects' continued failure gave rise to a wave of bills presented to state legislatures in order to at least partially solve the "problem" of undocumented immigration (Tuirán and Ávila, 2010; Varsanyi, 2010; and Hastings, 2013). Standing out in all these moves were the omnibus bills containing several packages in a single text and those that imply greater harm to undocumented immigrants and their families.

Arizona was one of the most active states, approving and carrying out policies against undocumented immigrants. Two policies from the 1990s should be underlined: 1) In 1996, Arizona's state Legislature passed a law requiring proof of legal residency to obtain a driver's license. It was created by a man who would be a key figure in developing the state's anti-immigrant policies, Russell Pearce, then head of the Department of Motor Vehicles of Arizona; and2) A year later, the city of Chandler, part of the greater Phoenix metropolitan area, implemented Operation Restoration. For five years, police stopped anyone who looked Hispanic and asked them to prove U.S. citizenship.

The first decade of the twenty-first century saw a huge increase in anti-immigrant policies in the state. In 2004, the Arizona Taxpayer and Citizenship Protection Act (Proposition 200) demanded proof of citizenship to be able to vote and access certain public services. This was supported by the Protect America Now group (pan) and the national anti-immigrant group Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). In 2005, the measure popularly known as the "anti-smuggling law" imposed punishment on anyone engaged in human smuggling, but also allowed punishment for those who hired those services as "co-conspirators" (Montoya Zavala and Woo Morales, 2011).

A year later, four more laws were passed by the legislature: Proposition 100, forbidding undocumented immigrants bail if accused of a crime; Proposition 102, preventing undocumented immigrants from receiving monetary compensation in civil cases; Proposition 103, making English the state's official language; and Proposition 300, banning undocumented immigrants from accessing state-funded educational services and assistance from the Arizona Department of Economic Security. The last makes access to higher educational systems difficult, since tuition rates triple for students without papers. Also in 2006, Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio used the ambiguous language in the anti-smuggling law to stop and jail undocumented immigrants. He also signed a 287(g) agreement with ice allowing approximately 170 state agents to be trained to carry out activities normally reserved only for immigration agents. The state funds earmarked for migration meant that emergencies would be ignored by state police, at the same time that many complaints were lodged for "racial profiling" and human rights violations. On January 1, 2008, the Legal Arizona Workers Act (lawa) went into effect, mandating that employers verify whether their employees are authorized to legally work in the United States. Plascencia (2014) states that there were practically no guilty verdicts under lawa and that this may have been due to the fact that Sheriff Arpaio and County Attorney Andrew Thomas's enforcement focused on apprehending unauthorized workers in workplace raids and through smuggling inspections.

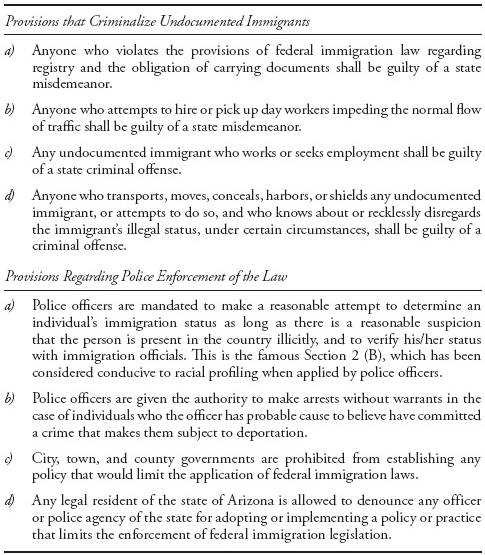

On April 23, 2010, Arizona Governor Janice K. Brewer (R) signed the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act (also known as SB 1070) into law.7 This omnibus state law has two types of stipulations. One is the kind that attempts to criminalize immigration and the second deals with enforcing the law (Iglesias Sánchez, 2010). According to McDowell and Provine, the Arizona legislation "is the first state law to directly challenge the federal government's claim of plenary power over enforcement of its immigration law" (2013:55). The second kind of stipulation includes the controversial Section 2, subsection B, which implies greater risk of police action through racial profiling, a subsection upheld by the Supreme Court in 2012.

Sinema (2012) shows how many of the elements included in this law were part of proposals presented in previous years, but that did not pass the two chambers of the legislature or were vetoed by then-Governor Janet Napolitano, Brewer's predecessor. That is, SB 1070 not only inherits the policies carried out in Arizona in recent years, but also grew up alongside them.

Table 1 shows the main stipulations in the Arizona law, regardless of whether they had injunctions filed against them or if they were ultimately struck down. This article does not attempt to explain why the law was approved with this concrete content, which would be an impossible task, but to explain its existence, its restrictions, and its anti-immigrant character.

Table 1 Voter Support for SB 1070

Source: Developed by the author based on Arizona State Legislature (2010); American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona (2010); and Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (2014).

The factors I think generated the support of the majority of Arizona voters for SB 1070 fall into three categories: economic, socio-cultural, and political. The demographic factor is also very important, but for reasons of clarity, it is presented here with the others.

Economic Factors

Two economic arguments will help us understand the support of the Arizona electorate for restrictive immigration policies. First of all, when the economy goes into recession or a downturn, the public tends to want to restrict immigration more. The second factor is the perception of a possible cost of undocumented immigration for taxpayers in the state, which leads to support for restrictive measures against immigration.

The U.S. 2008 Great Recession came to Arizona in September 2007 (Hogan, 2010). A large part of the state's immigrant workers were in construction, where more than 140 000 jobs were lost, according to estimates from the American Community Survey (ACS). This meant that the undocumented immigrants hired during the construction sector's mega-boom were the first to lose their jobs. They then began to be seen both as a potential tax burden for the state and as a threat to jobs for the native-born. Polling expert Bruce D. Merrill said that in 2010 in Arizona, the number of persons who thought that Hispanics were taking jobs away from U.S. Americans rose (Archibold and Steinhauer, 2010). While many anti-immigrant measures were created before the crisis, as the preceding paragraphs show, one of the potentially most damaging measures for undocumented immigrants, SB 1070, appeared a little over two years later.

On the other hand, "The most careful and objective studies of this topic conclude that, while immigrants (illegal and legal) represent a net fiscal gain to the federal government, they are often a net burden to affected states and a definite fiscal negative to local governments" (Fix and Passell, 1994). The high level of undocumented immigration into Arizona was a concern for taxpayers,8 some of whom considered they were subsidizing this sector of the population unjustifiably, regardless of whether this was true or not.

Socio-Cultural Factors

The responses and reactions of native-born Arizonans to immigration depend to a great extent on their perceptions of the magnitude of migratory flows and "stocks" and of their characteristics (documented or undocumented, ethnic origin, phenotype, culture, etc.).9

In the last 30 years, a very important demographic change has occurred in Arizona:

Arizona's population grew to more than double its size: from 2.7 million in 1980 to 6.5 million in 2008, going from twenty-ninth to fourteenth on the list of most populated states in the country. Latinos represented two-fifths of the almost 3.8 million inhabitants who swelled the ranks of the state's population from 1980 to 2008, as the Latino population grew to almost four times its original size, from almost 441 000 in 1980 to nearly 2 million in 2008. (Saenz, 2010)

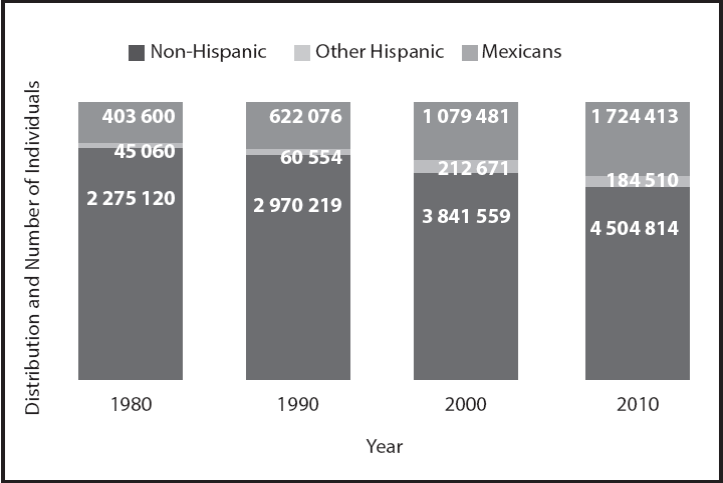

In 2009, the Hispanic population surpassed the two-million mark. Graph 1 shows how it has grown more than the rest of the population in three decades. In 1980, the Latino population was 16.5 percent of the total, while, in 2011, it was slightly more than 30 percent. It should also be underlined that most Hispanics in Arizona were of Mexican origin (90 percent in 2010). Between 2000 and 2010, the number of Hispanics or Latinos not of Mexican origin dropped.

Source: Developed by the author using Ruggles et al. (2010) and ACS (2010).10

Graph 1 Distribution and Size of Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and Mexican Populations Resident in Arizona (1980-2010)

The outstanding, rapidly increasing demographic weight of the Mexican population in the state sparked fear of a loss of the nation's supposed single culture, fear about the country's future ethnic/racial composition, and fear about the political prominence and status of the growing Latino population. These three fears are pointed out by Plascencia (2013). This implies that the native-born population favored the measures that supposedly would put the brakes on these changes.

In addition, the state of Arizona has historically been known for its xenophobia and occasional racism and the policies it has traced along those lines. As Plascencia (2013) points out, in 1914, its second year of statehood, its first governor passed the Act to Protect the Citizens of the United States in Their Employment against Noncitizens of the United States in Arizona. In contrast with current laws, mainly focusing on undocumented immigrants, that law was against all non-citizens, the majority of whom were Mexican. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the frame of mind prevalent in Arizona was made clear "when it refused to declare a paid holiday to celebrate the life of civil rights champion Martin Luther King, Jr." (Notimex, 2010).

Finally, it should be pointed out that anti-immigrant policies have created an atmosphere of discrimination against the Hispanic community "without papers" in Arizona that makes the harsh policies against them seem natural. According to Tonatierra leader Salvador Reza, Arizona became the most racist state in the United States, surpassing others that had historically been seen as topping that list, like Alabama and Mississippi (Lugones, 2008).

Security Factors

After September 11, 2001, the security paradigm definitively permeated all levels of government (local, state, and federal).

Immigration to Arizona, particularly undocumented immigration, was associated in people's minds with drug trafficking, delinquency, and crime. The populist rhetoric of politicians like Russell Pearce, the Republican senator who promoted the Arizona law, and Governor Brewer merely corroborated and encouraged that association. For Pearce, undocumented immigration was undoubtedly a burden for the state, and also constituted a threat to security:

Why did I propose SB 1070? I saw the enormous fiscal and social costs that illegal immigration was imposing on my state. I saw Americans out of work, hospitals and schools overflowing, and budgets strained. Most disturbingly, I saw my fellow citizens victimized by illegal alien criminals. The murder of Robert Krentz-whose family had been ranching in Arizona since 1907-by illegal alien drug dealers was the final straw for many Arizonans. (Pearce, 2010)

During her campaign for reelection, Governor Brewer stated that immigration was out of control in Arizona and that most immigrants were bringing drugs into the state (Magaña, 2013).

Drug trafficking and human smuggling in Arizona were among the highest of all along the Mexico-U.S. border. The U.S. Department of Justice's National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC) catalogued Arizona as a high-intensity zone for drug trafficking. In 2010, it said that Arizona was first in the nation with regard to the entry of Mexican marihuana and an important port of entry for other kinds of drugs. "Arizona's Senator John McCain said that at least 6 000 troops should be sent in because in his opinion, the state was heading the nation in marihuana confiscations; experienced 368 kidnappings in 2008; and had the highest rate of crimes against property" (Mendoza, 2010). However, official U.S. sources categorize the state of Arizona and its cities as increasingly safe in the period when immigration was on the rise. "Most studies have shown illegal immigrants do not commit crimes in a greater proportion than their share of the population, and Arizona's violent crime rate has declined in recent years" (Archibold and Steinhauer, 2010). The same is the case for all kinds of crime:

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, the rates of crimes against property and violent crime, which includes murder, assault, and rape, have been dropping in recent years. The rate of violent crime dropped from 512 per 100 000 persons in 2005 to 447 per 100 000 persons in 2008. The rate of crimes against property also dropped from 5 850 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2005 to 4 291 per 100 000 in 2008. (Immigration Policy Center. American Immigration Council, 2010, cited in Cruz, 2010:8)

Therefore, the case of Arizona coincides with many other studies carried out in the twentieth century that "have documented that immigrants are typically infra-represented in crime statistics" (Martínez and Lee, 2004:2).

Despite this evidence, the reality of security and immigration does not prevail, and, once again, what matters are perceptions; immigrants were seen by the Arizona citizenry as the cause of insecurity, and, as a result, the public was amenable to supporting anti-immigrant measures.

To close this section, I want to point out that the media collaborated in different ways in generating negative perceptions of immigrants and in the unjustified increase in the different kinds of fears mentioned above linked to the demographic change. In the first place, politicians used the media to disseminate their anti-immigrant rhetoric and ideas to the public, especially the citizens whose ideas jibed with theirs. Secondly, the media presented a distorted image of the reality of migration, tending to portray it as completely out of control and associating immigrants with delinquency and crime. Although there are still few studies about the impact of the mass media on the native-born population's attitudes and perceptions of migration, some authors consider it important. For example, Zolberg (2009) argues that the shift in perceptions of migration in the 1990s toward a more negative view is due to a series of events that gained certain notoriety in the media in that decade and that jumpstarted the first feelings of invasion and threat. Among them were the "Nannygate" scandal about undocumented migrants hired as nannies by then-candidate for attorney general, Zoé Baird, during the Clinton administration; the arrival of the Golden Venture, a ship from Fujian, China, with more than 300 undocumented immigrants aboard; the growing "waves" of Haitians and Cubans coming into the country; and the assaults and rapes perpetrated by some immigrants.

The Politics of the Arizona Law

In my opinion, several factors contributed to political leaders' deciding to support a bill like SB 1070. The following is an analysis of each.

Electoral Interests

Opportunistic politicians can use certain anti-immigrant sentiments in the population to their political advantage. SB 1070, despite its bitter nature, had majority support in U.S. public opinion in the months before and after its partial entry into effect.

"Three different polls (one by the pew Research Center, one by the Wall Street Journal-NBC, and one by McClatchy-Ipsos) reveal that around 60 percent of [U.S.] Americans support the Arizona Law" (Oppenheimer, 2010). The state's residents were even more in favor of it; one poll put the figures at 70 percent in favor and 23 percent against (Francis, 2010). If the majority of the population agrees with a law, then signing it can help you ingratiate yourself with them. The reality is that Arizona SB 1070 is part of the Republican Party strategy for the U.S. midterm elections to exploit the public's fear in the face of the loss of national identity due to the "invasion" of immigrants of Latino origin and its resistance to cultural diversity. We can say that support for the Arizona law helped get Janice K. Brewer elected, or, to be more explicit, it "catapulted her to the governor's seat" (Durand, 2013:95). Rasmussen surveys and analyses validate this idea. According to them, Brewer's political fate in the state was reversed due to her signing and firm support for the state immigration law. At that time, 58 percent of the state's voters approved her performance as governor, while 42 percent disapproved. Sixty-one percent supported the immigration law, while 34 percent opposed it. More than 60 percent of Arizona voters supported the law after Brewer signed it in April of that year. Eighty-one percent of those who supported the law voted for Brewer. Her opponent, Goddard, who came out against the bill, received the support of 85 percent of the voters who opposed it (Rasmussen Reports, 2010).

When Senator McCain ran for reelection, his campaign was based to a large extent on the issue of enforcement of immigration legislation and support for SB 1070 (Magaña, 2013).

It should be pointed out that most members of the Democratic Party in Arizona opted for inaction and did not face down SB 1070, possibly due to its popularity among the public and the little power they had in the legislature in the "era of SB 1070." The Democratic senator from Arizona Steve Gallardo was one of the few who raised his voice against it; for example, in January 2012, he introduced a bill into the legislature against it (Notimex, 2012a).

Party Politics

Ideologies and interests of all kinds lead parties to go after specific aims; one of them can be restricting immigration. The most restrictive state policies against undocumented immigrants have been promoted by the Republican Party. However, not all Republicans on state and federal levels agree with these measures.

A large part of the Republican Party defended the Arizona law, expressing its support for state immigration legislation and against the administration of President Barack Obama. Former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin publically supported it, saying, "Jan Brewer has the 'cojones' that our president does not have to look out for all Americans-not just Arizonans-but all Americans in this desire of ours to secure our borders and allow legal immigration to help build this country" (CNN México, 2010). John McCain, Republican Party presidential candidate in 2008, defended the Arizona Law, considering that the control of migratory flows was directly related to national security. And, undoubtedly, the members of the most conservative faction of the Republican Party, the Tea Party, promoted and supported SB 1070.

In line with Roxanne Doty (2007), Javier Durán points out that the doctrine of attrition through enforcement "has become the cornerstone of a third way of dealing with the problem of undocumented immigration in the United States. For the anti-immigrant right, attrition through enforcement is a better option than immigration reform or mass deportations" (Durán, 2011:93). The text of SB 1070 expressly states that its aim is to turn this doctrine into public policy in all local and state government agencies.

Looking at Other States

Generally speaking, we can say that the Arizona law is heir to the process of state legislation on undocumented immigrants that has been ongoing for years in the United States, particularly vigorously in states like Arizona. This phenomenon presupposes the reinforcement of what has been called federalism in immigration, a de facto situation in which states have greater competencies in matters of immigration than could be expected given the "plenary power doctrine".

However, links can also be found between SB 1070 and policies implemented by other states and even the federal government in a more specific sense. Durand states that Arizona's SB 1070 "is the direct consequence of Proposition 187, the 1996 IIRAIRA, and section 287(g)" (2013:106). It is my contention that the connection between SB 1070 and other important pieces of legislation is complex. As previously pointed out, Proposition 187 was voted into law in California and "heard and heeded" by federal legislators, who promoted a legal reform that included the passage of the IIRAIRA, which in turn included section 133, adding section 287(g) to the Immigration National Act. In this sense, although Proposition 187 was struck down, it may have been the example for Arizona as to how a polemical state law can lead to legislative changes on the federal level. That is, it demonstrated the strategic sense of passing state laws in conflict with the existing legal framework if the content of a state law, regardless of whether it is vetoed, abrogated, or struck down by the courts, can end up being part of the content of a federal legal reform (the following section of this article will deal more with this). This is nothing new, since it has happened on several occasions in the past. In any case, even though the content of the two laws is quite different, Proposition 187 is the paradigm precedent for SB 1070 due to its importance in the media, its use in elections, and the fact that it was challenged in court.

For its part, section 287(g) delegates immigration functions to state and local bodies in terms of police enforcement of immigration law, since the states and counties can decide whether they collaborate with ice or not. SB 1070 took new steps in this direction, increasing police powers in Arizona to include verifying the immigration status of individuals and making arrests.

Interaction with the Federal Government

State immigration policies interact with federal policies and can also impact the federal debate. This section will examine what may have been the intent in passing SB 1070 with regard to federal policies and immigration debate. The law contains at least three stipulations that do not jibe with the existing legal framework.

Following the literature, in this article I look at three kinds of intent with regard to federal policies and debate that Arizona may have had in passing SB 1070:

The desire to "send a message" that things are going badly and a federal immigration reform and strict enforcement of federal immigration law are necessary. This idea of sending a message was cited by Kitty Calavita in 1996 for the case of Proposition 187. This option is very present in the discourse of several politicians who point out that the Arizona law is not a definitive solution, which will only be reached with a reform of the entire federal immigration system. For this option, it is not particularly important that the law actually be passed; what is important is the effect it could have as an incentive for federal action.

A lobbying strategy for the new aspects in SB 1070 to be taken into account on a federal level. Alexandra Filindra (2009) states that the states have used their legislative capacity to keep immigration high on the agenda and to make sure their interests are taken into account. In contrast with the idea of "sending a message," what is important here is not simply demanding that the federal government act, but that it do so in a way that the state in question wants it to, through an immigration reform that includes Arizona's wishes, through its law enforcement policies, etc. Several reflections by academics and political statements on SB 1070 turn on this idea. Singer (2010) asks herself if the Arizona law can become national; in 2012, Mitt Romney said he saw "a model in Arizona" for future immigration policy in the United States (Notimex, 2012b); for McDowell and Provine (2013), the law may have had the aim of pushing the debate on undocumented immigration in the direction of enforcement policies; and, finally, Pearce himself said that "We are at the front of the parade," and, "We have changed the debate in Washington D.C." (cited in Biggers, 2012:3).

Supporting the idea that states can have their own immigration policies in certain concrete aspects, about everything directly related to the immigrant, thus reinforcing what was previously defined as "immigration federalism." That is, what a law like SB 1070 would intend would be to get more decision-making power over immigration issues. Throughout its recent legislative history, this border state has shown its interest in pushing the limits of its relationship with the federation.

Economic Interest Groups and Anti-Immigrant Organizations

Interest groups have been vitally important for explaining U.S. federal immigration policies (see Freeman, 1995). However, in this case, SB 1070 does not seem to have been on the agenda of economic interest groups, possibly because they did not perceive it as a threat. However, the multiple negative effects on the economy from the boycotts launched both in the United States and in Mexico spurred these groups to mobilize against the new anti-immigrant statutes. According to Kyrsten Sinema (2012), the Arizona Chamber of Commerce, business leaders and groups, brought pressure to bear against more anti-immigrant measures being passed in the state.

The anti-immigrant groups not rooted in economic issues collaborated technically with SB 1070. Kris Kobach, associated with FAIR, in particular, was outstanding in his participation in authoring the draft bill. In addition, in the past, Kobach participated in establishing the bill's legal bases: in May 2010, "The Washington Post wrote that 'the author of the Arizona law [Kobach] ... has cited the authority granted in the 2002 memo [that he helped draft] as a basis for the legislation'" (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2011). Sinema (2012) exhaustively describes and analyzes the relationship between these groups (fair, the American Legislative Exchange Council, and their members) and the Arizona legislature.11 These groups' strategy seems clear: attempting to influence as much as possible the legislative and political processes on different levels of U.S. government to promote their anti-immigrant agendas to the maximum.

Conclusions

In recent years, one of the most important challenges Arizona has faced is what to do about the undocumented immigrants residing inside its borders. The magnitude of the challenge is determined by the volume and characteristics of the undocumented population, by Arizona's socio-cultural and economic context in the last decade, and by the absence of a federal immigration policy that effectively controls the flow of migrants. While other states opted for policies to integrate immigrants or for laissez faire, the state of Arizona saw the emergence of a series of increasingly harsh anti-undocumented-immigrant policies.

In this context, I conclude that it is highly probable that SB 1070 was promoted by Arizona's Republican political leaders to make electoral gains, given the huge support from the public that it had, and to push an anti-immigrant agenda in the state and, indirectly, on the federal level.

I think that the huge support of Arizona's voters for SB 1070 derived from economic, socio-cultural, and security factors. After the economic crisis, part of the Arizona electorate perceived immigrants as the cause of unemployment and wage stagnation. Also contributing to increased support for the law was a fear of the loss of a supposed monocultural society and about the future ethnic/ racial composition of the United States, stemming from intense demographic change. In both cases, xenophobia and racism played a fundamental role. In addition, voters associated the problems of violence and delinquency in the state with undocumented immigrants; this was yet another reason to be in favor of policies against undocumented immigrants like the Arizona law. The media and Republican political leaders notably bolstered all kinds of negative perceptions about undocumented immigrants in Arizona.

Arizona Republican political leaders seem to take great interest in fostering an anti-immigrant agenda based on the attrition-through-enforcement doctrine as a strategy for dealing with the "problem" of undocumented immigration; to do that, they had the technical support of anti-immigrant groups. Today, after the 2012 Supreme Court decision, SB 1070 is considered an important advance in anti-immigrant legislation in Arizona.

While it is unlikely that the legislators who passed SB 1070 anticipated the media coverage that it eventually received, they probably did foresee a conflict with the federal government and the repercussions that this would have in the national debates on immigration, making it a mechanism to put the issue at the top of the agenda and redirecting it the way they wanted, given the precedent in recent history of Proposition 187. In other words, the possible unconstitutionality of stipulations in SB 1070 did not impede, but rather increased, the possibilities of the law's success in terms of advancing the agenda against undocumented immigrants on a federal level.

In the coming years, it will be possible to conclude whether what began as a political and demographic "experiment" in the state of Arizona, SB 1070, is somehow expressed in federal immigration policy.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)