Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.7 no.2 Tijuana jul./dic. 2013

Artículos

Psychological State of High School Students with Migrant and Nonmigrant Parents*

Estado psicológico en jóvenes de secundaria hijos de padres migrantes y no migrantes

Laura Oliva Zárate, Luis Rey Yedra, Elsa Angélica Rivera Vargas, María del Pilar González Flores y Dinorah León Córdoba

Universidad Veracruzana.

Date of receipt: October 27, 2011.

Date of acceptance: April 11, 2012.

Abstract

The phenomenon of migration can influence vulnerability among family members, including teenagers who assume roles they are not ready to perform. The aim of this paper is to identify behavioral problems in teenage children of migrants and non-migrants from Xalapa, Mexico. The CBCL 6-18 years and the questionnaire on factors related to behavioral problems and migration were administered to a representative sample of 2 371 high school students ages 13 to 17 years. The results show that this is an at-risk population that is particularly vulnerable since over 40 percent of adolescents have some sort of problem such as aggression, anxiety or introversion. The types of problems identified and the relationships found concerning demographic variables and migration are discussed.

Keywords: behavior problems, CBCL 6-18, family, drugs, Xalapa, Mexico.

Resumen

El fenómeno migratorio puede influir en las condiciones de vulnerabilidad entre los miembros de una familia, incluidos los hijos adolescentes, que pasan a asumir roles para los que no están preparados. El interés es identificar los problemas de conducta en adolescentes hijos de padres migrantes y no migrantes de Xalapa, México. Se aplicó el CBCL 6-18 años y el cuestionario sobre factores relacionados con problemas de conducta y migración a una muestra representativa de 2 371 estudiantes de secundaria de entre 13 y 17 años de edad. Los resultados indican que se trata de una población en riesgo, especialmente vulnerable porque más de 40 por ciento de los adolescentes tienen algún problema como agresividad, ansiedad e introversión. Así mismo son abordados los tipos de problemas identificados y las relaciones con variables demográficas y la migración.

Palabras clave: problemas conductuales, CBCL 6-18, familia, drogas, Xalapa, México.

Introduction

Nowadays, economic, social, political and environmental changes impact individuals and society in general, meaning that human beings implement mechanisms to adapt to new conditions. This is by no means easy, since in some cases, it directly affects the decision-making process to achieve their goals, one of which is to improve their living conditions. Until the mid-20th century, since the states with the highest migration rates were those adjacent to the United States, Veracruz was not considered a state with a migrant tradition, especially because in the early to mid-20th century, it was a state that required labor from other states to work in its agriculture, industry and oil. Over time, it has gradually come to be considered one of the main states with high emigration rates, due, among other things, to the economic crisis, particularly since the 2001 recession. The coffee crisis has also triggered migration in the state of Veracruz (mestries, 2003; Quesnel, and Del Rey, 2003).

Migration creates benefits. However, it also has other implications: migrants' health deteriorates as a result of the great physical strain to which they are subjected by their employers (Bustamante, 1988). Psycho-emotional aspects are altered when a family member emigrates to another state in Mexico or outside the country, affecting relations between family members and friends. According to reports from previous studies on these issues, the mental health of those who stay behind and those who leave may be affected (Chaney, 1985). The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) reports that migration has a negative impact on Latin American children, since they experience family disintegration and a lack of protection (Pierri, 2006).

The migratory phenomenon may influence the vulnerability of family members. Teenagers, whether only children or with younger siblings, together with parents, assume different roles within the family nucleus. Thus, if either or both parents migrate, other members of the nuclear family assume roles they are usually not qualified to perform, resulting in frustration, anger and depression, impaired school performance or even dropping out. Adolescents may be attracted to groups of teenagers with whom they share ways of thinking, feelings and attitudes, with unhealthy forms of expression such as vandalism, drug use, and other self-destructive behaviors (Mummert, 2003). The nuclear family is considered a "Primary group formed by parent(s) and child(ren) and possibly other relatives linked by multiple, varied bonds who support and help each other on a reciprocal basis and perform several functions for their mutual benefit and that of society" (Ribeiro, 2000). Other functions include child raising and children's primary socialization to develop their psychosocial identity (Macías, 1994).

During adolescence, deviations may occur, or even psychological disorders that must be treated promptly. Hence the interest in identifying behavioral problems in high school students as well as the factors that may be associated with these problems.

The Psychosocial Impact on the Migrant's Family

Behaviors and Syndromes in Teenagers

Several studies have reported gender differences in terms of individual disorders, the rate of problems being considerably higher in male than female teenagers (Wolff, and Ollendick, 2006). Although statistics show that behavioral and mental problems are similar between men and women, there are clear differences by sex and age in regard to depression (who, 2003), which is more common in women, whereas addictive substance abuse and antisocial personality problems are more common in men. Sex differences in depression levels emerge during adolescence (Wade, Cairney, and Pevalin, 2002).

When a relative emigrates, family dynamics are negatively altered, impacting the mental health of some of its members. This is exemplified in a study conducted in two communities in Oaxaca, where it was found that families with a migrant relative had a greater incidence of psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, domestic violence and alcoholism. moreover, a higher percentage of those who emigrate are parents and their male sons (Aguilar-Morales et al, 2008).

Another study to identify the psychosocial effects of international migration on the mental health of migrants' teenage children was conducted by Moya and Uribe in 2007 at the Centro de Estudios Epidemiológicos de Zacatecas, in Mexico. The sample consisted of 310 teenage children of migrants living in rural communities in that state. To this end, a test was administered to identify the psychological characteristics of depression. The results showed that there is no direct correlation between depression symptoms and being the child of a migrant. Instead, teenagers displayed these symptoms when one or both parents worked outside the home. The authors add that in these communities the elements that contributes to the generation of depressive symptoms in the migrants' young children are a result of the conditions of the rural contexts in which families are left. In addition to studying, young children work to support their families; the father is absent due to international migration, and the mother's role is changing.

It is important to note that anxiety and depression are among the behaviors classified by Achenbach (2001) as internal behavior (see table 1). Moreover, Jones et al. (2002) found that external behavioral problems are the result of poor parenting coupled with maternal depression, which is directly related to internal behavioral problems. This is understandable since when the mother stays behind, she assumes responsibility for the entire family. For some mothers, being solely responsible for the burden of parenting coupled with the husband's insecurity can lead to certain emotional disorders such as depression.

Other studies have shown that both introversion and somatization—considered internal syndromes by Achenbach (2001) (see table 1)—occur almost twice as often in women as in men. Sarason, and Sarason (2006) found that for women, the likelihood of depression is twice as high as it is for men, since they tend to offer more emotional and material support, which produces equal or greater stress. One possible explanation suggests that hormonal factors—implicit in the menstrual cycle—and the increase of depression symptoms in women, might be affecting mood as well as the expression of somatic distress.

The Migrant's Family

The guidelines governing the type of interaction between members of a family group constitute a growing source of interest for those engaged in the study of the family, by virtue of their implications for the lifetime of its members, in addition to the fact that the family serves as a mediator in various social processes, such as migration in this case.

The fact that many families disintegrate is a consequence of migration. This leads to the creation of a new form of fragmented family, called "transnational family" by Falicov (2007), which has advantages and disadvantages for both those that leave and the rest of the family, which remains in the country. They may display symptoms that may be related to the departure of this relative since their everyday lives are altered.

Whereas in the past, those who emigrated were exclusively parents—males—nowadays it is teenager offspring of either sex and mothers who in many cases are single, who abandon their children or, at best, leave them with relatives or neighbors in their community, as reported by Garduño (2008). In this respect, the author adds that the Pew Hispanic Center reports that 42 percent of women who migrate are aged between 30 and 44 and 28 percent are aged between 18 and 29 with 30 percent belonging to other age groups.

When wives are left behind, they often experience various fears about their partners, which begins with their departure, such as: wondering whether they will be able to reach their destination; whether they will be healthy, where they are going to live or with whom; whether they will abandon their families or fail to send remittances and whether they will form a new family, or become involved in drugs or alcohol. In this case, they are the ones who deal with any problems that occur at home, while coping with the economic situation in the first few months before the first remittances arrive (Salgado, and Maldonado, 1993; Salgado, 1994, 1996).

As one can see, when one parent migrates, other members of the nuclear family assume roles they are not usually qualified to perform. In the event that both parents leave, children may be looked after by other family members or neighbors, creating a feeling of abandonment, frustration, anger, depression in children and adolescents, reflected in a decline in school performance or dropping out, or feeling attracted by peer groups with whom they share ways of thinking, feeling, attitudes and unhealthy forms of expression such as vandalism, drugs, and other self-destructive behaviors as noted by Mummert (2003).

On his return, the spouse creates emotional tension in the family, since during his absence, family members' roles were adjusted. The mother, who is usually distressed, tries to restore the father to the same role he had before he emigrated and serves as a mediator between him and the children. This situation is rejected by the teenagers since they are no longer willing for the father to take control of their lives. Another source of distress for wives is that they may become pregnant only to be abandoned again (Rouse, 1991).

The feeling of abandonment experienced by migrants' children and its respective consequences, exacts a high emotional toll in exchange for the family's economic well-being since maternal or paternal figures cannot be replaced by other relatives or guardians. This situation is responsible for another of the costs of migration: lack of references. Not having family models or the transmission of their cultural values coupled with the absence of guidance and support for healthy psychosocial development, as noted by Pinazo, and Ferrer (2001), creates inadequate socialization that alters social networks and the learning of socialization.

The new cognitive-behavioral patterns impact family members who experience changes in the way they dress, which is uncommon in rural Mexico or use drugs (Pinazo, and Ferrer, 2001). The next session refers specifically to family relationships as well as the impact of parental migration on the family's mental health.

Family Relations

From the time of the formation of the couple, the family undergoes a series of processes that can strengthen or destroy it, which include various factors that affect the family group and each of its members: the process whereby the couple meets, the stages of family development, the interpersonal relationships of the couple and between them and their children, the forms of communication and the expression of emotions will all determine whether the family is functional or dysfunctional.

Depending on its composition, the family is either called nuclear, with parents and children, or extended, with parents, children and other relatives. The latter form of organization is more commonly observed in areas with low socioeconomic status in urban settings and rural communities, due to the need to support each other economically and organize for farming and/or livestock activities (Tuirán, 2001). In the past, the coexistence of both types of families was common. Nowadays, parents decide to live alone with their children in order to be responsible for raising them. Although this is ideal, in many households where migration occurs, children, or children and their mothers, may make the decision to cohabit with the extended family in order to help them with their children as regards responsibilities, decision-making and financial aspects.

Another key factor in families' lives concerns the rules of coexistence. These constitute their inner strength, which enables them to indicate the path to be taken to achieve the harmonious development of the family as a group and of each of its members. Some of these rules are for general observance and others are private. However, it is important that they all emanate from the family nucleus, mainly from the parents who convey them to those involved, regardless of age. There are also implicit rules (particularly related to the transmission of culture and social norms) that should be explained to prevent misunderstandings and achieve the personal commitment of each member of the group. Having clear, explicit rules allows the family to advance towards a process of development (Yedra, and González, 2002:31). This situation may or may not be adversely affected by the absence of one or both parents.

The psychosocial functions performed by a family should not be overlooked; Macias (1994:143-145) distinguishes the following: 1) satisfaction of biological needs of subsistence and physical well-being; 2) promoting ties of affection and social union; 3) facilitating the development of individual identity linked to family identity; 4) providing models of psychosexual identification; 5) acquisition and integration of the social roles associated with social structure and organization; 6) initiating and promoting learning and creativity in children; 7) transmission of values, ideology and culture.

It should be noted that values are learned through experience, particularly in the family of origin. It is not enough to teach them or talk about them; they must be lived on a daily basis and, as some authors such as Yarce (2004:13) have pointed out, they are still alive in our society and are necessary to ensure quality of life in people and families. Teenagers may have a more or less clear idea (conceptually) about values but they refer to them as desirable things or situations that are worth living (González, 2007:159).

In addition to this, there are certain situations faced by today's families: the variety and availability of addictive substances which teenagers may use from an early age, exacerbated by the phenomenon of the migration of one or both parents.

Use of Addictive Substances

The status of addictive substance use in Mexico is similar to that in the rest of the world and the city of Xalapa is no different, as shown by the data reported by Villatoro, and Medina-Mora (2002:127), who report a consistent increase in drug use, especially cocaine, tranquilizers and amphetamines among the student population and show how this problem has evolved over the past fifteen years.

In the south of the country, alcohol has been considered the gateway drug for 85 percent of users, according to information provided by NGOs and the Centros de Integración Juvenil (CIJ) (Secretaria de Salud-DGE, 2003); likewise there has been an increase in the number of users among teenagers, coupled with a decrease in age of onset. It has been found that some put forward the use of addictive substances to ten and even eight years, with alcohol or ecstasy, according to declarations by the coordinator of Prevención y Atención a las Adicciones of the Secretaria de Educación y Cultura del Estado de Veracruz (Morales, 2004). For many, onset occurs before the legal age for purchasing products such as tobacco and alcohol, and it has been recognized that increased consumption occurs among students ages 16 or older, except for those who use inhalants, whose consumption is common among those under 16.

More recently, the Centro de Integración Juvenil and the Sistema de Información Epidemiológica del Consumo de Drogas (SIECD) presented semiannual data from the second half of 2004 to the first half of 2009, as reported by users under treatment at the Centro de Integración Juvenil in Xalapa (CIJ-SIECD, 2010). In the first half of 2009, alcohol continued to be the most commonly consumed substance (80.2 %), followed by tobacco (70.3 %) and marijuana (69.2 %). This preference was maintained in all the six-month periods investigated, both for ever use and for consumption in the past 30 days.

According to Pinazo, and Ferrer (2001:108-109) risk factors can be found in at least four levels: individual, family, peer group and community. Regarding the first, they mention drug use by models (such as parents); seeking new sensations; low religiosity; low self-acceptance; poor academic performance and unawareness of the harmful consequences of drug abuse.

Regarding the family level, they mention: ineffective family influences; a history of alcoholism, drug use by parents and older siblings, and lack of warmth between parents and children. Likewise, these authors note that social and environmental variables may be predictors of drug use, noting that family breakdown can lead to inadequate socialization by altering the variables related to social learning.

School Environment

Schools have been recognized as one of the key micro-social areas due to the considerable number of hours teenagers spend in them every day. Attention should be paid to aspects of students' performance and development that may be indicative of certain problematic situations, such as: lack of motivation to study, dropping out, marginalization, problematic family situations and, in general, problems of social adjustment of their population, in order to be able to guide them toward healthy behavior. Moradillo (2002) argues that school becomes a powerful development factor for teenagers when interpersonal relations between teachers and pupils are good, with an active, participatory style of work and clear regulations involving democratic values and discipline. For his part, Becoña (2002), emphasizes the control teachers must exert over their students through close monitoring and treatment in accordance with the evolutionary stage they are undergoing, which promotes students' holistic development.

Method

A quantitative, cross-cutting method was used to analyze issues with a psychosocial impact on the migrant's family, the behavioral and social problems of the teenage children of migrants and non-migrants; the impact on the family and family relationships, and their impact on the school environment. The data were subjected to a chi square (X2) statistical test and univariate and bivariate analysis.

Subjects

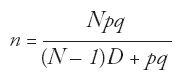

The total population of high schools in Xalapa consisted of 54 schools divided into four categories: telejunior high schools, official junior high schools, private schools, technical schools and others. In order to obtain a significant statistical sample, a random method was used with the following formula:

The sample consisted of 2 371 teenagers from the city of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico, whose ages ranged between 12 and 17, belonging to different geographical areas in the city. The result was a sample of 36 high schools with a reliability of 95 percent, distributed as follows: 13 telejunior high school, five official junior high schools, 11 private high schools, five technical colleges and two other types of school.

After obtaining the sample of schools, the sample of students was obtained by using the same formula, with a result of 2 371 of the 15 715 students enrolled. On the basis of these results, the questionnaires were proportionally distributed by schools and by shift (morning and evening) where appropriate. The student sample was distributed as follows: 516 at telejunior high schools, 696 at official junior high schools, 266 at private schools, 709 at technical and 184 at other schools.

Overall, 51.64 percent of the students interviewed were female and 48.36 percent male, of whom 32.29 percent were studying in the evening shift, and 67.71 percent in the morning. As for age, 14.46 percent were 12, 33.78 percent were 13, 36.65 percent were 14, 12.64 percent were 15 years; 2.06 percent were 16 years, and a minority of them were 17, accounting for 0.43 percent of the sample.

Instrument

Two instruments were used for the data collection:

1. Questionnaire on the behavior of children ages 11 to 18 years, drawn up by Thomas Achenbach (2001). This is a standardized instrument that allows behavioral/emotional problems to be evaluated, based on descriptions. The checklist for child behavior used in this research is a 112-item questionnaire to be answered by the young people themselves. It is designed to identify syndromes of problems that tend to occur together. The names of the seven syndromes are considered brief descriptions of the items comprising them rather than diagnostic labels. Table 1 shows the syndromes and their respective behaviors.

2. Questionnaire on factors related to behavior problems and migration. This instrument consists of an introduction-explanation to place the person answering the survey. The first part contained questions concerning general information about the informant while the second consisted of 16 open and closed questions grouped into three dimensions: school environment, family relations and migration.

Both instruments (the Achenbach questionnaire and the questionnaire on factors related to problem behaviors and migration) were administered to each of the participants at their schools.

Results

Behaviors and Syndromes in Adolescents

The data showed that 13.75 percent of the student population attending school in the city of Xalapa were young people, one or both of whose parents were migrants in the United States. Of these, in 65 percent the father was a migrant, followed by the mother (12 %) and low percentage, two (2 %) and 20 percent did not answer. They were also asked about how they felt about the father's absence, to which 40 percent replied that they felt bad; 30 percent said that they felt good and only five percent said that they were indifferent.

Regarding the behavior problems reported by young people themselves, overall, 59.9 percent can be said to be within the normal range, 16 percent in a borderline range (outside the norm without being clinical), while 24.1 percent of the respondents were located within the clinical range. Likewise, table 2 shows the syndrome in relation to the group. The syndrome with the highest percentage—in the clinical range—is aggressive behavior in both groups.

This finding corroborates what studies such those by Farrington (1989), Trianes (2000), Tattum and Lane (1989), Whitney and Smith (1993) show regarding aggressive behavior in age groups, which is understandable given the stage of transition in which youth is located, characterized by behaviors such as disobedience, being demanding, rebelliousness, among others, which could become a problem of adaptation at a later age.

There are statistically significant differences between the children of non-migrant and migrant parents, since the latter have a higher percentage in the clinical range in behaviors such as anxiety, somatization, social problems, attention problems, aggressive behavior and rule-breaking (see table 2). They become silent, unsociable and do not engage in group activities.

In a second analysis, the chi square test was used to study the dependence or independence between sociodemographic variables (sex and age) and syndromes (see table 3). A statistically significant difference was observed in relation to sex and certain syndromes, since males in the clinical range have a greater percentage of behaviors such as introversion, somatization, aggressive behavior and rule-breaking, while a higher percentage of females fall within the clinical range of attention problems.

In relation to age and syndromes, the χ2 test shows a difference in introversion syndromes (χ2 = 26.098, gl = 10, p < .05) social problems (χ2 = 24.436, gl = 10, p < .05) thought problems (χ2 = 26.141, gl = 10,p < .05), attention problems (χ2 = 36.362, gl = 10, p < .05) and aggressive behavior (χ2 = 54.703, gl = 10, p < .05), showing that young adults (between 16 and 18) have higher percentages in the clinical range of these syndromes.

The Migrant's Family

Family relations

In addition to undertaking the analyses presented above, the CHAID segmentation algorithm (Chi Square Automatic Interaction Detection) was administered, due to the large number of variables. A special situation often emerges in which one of them in particular plays a key role, the purpose of this article being to attempt to explain it using the rest of the variables. This was done using the variables contained in the questionnaire on factors related to behavior problems, which identified the best predictors, on the basis of which subgroups were created that could potentially explain the dependent variable. In this respect, it was found that the best predictors of behavior problems were teens whose parents had bad or fair couple relationships and also had bad relations with their families. This is confirmed by the fact that 60.32 percent of the sample reported having family, school and/or behavior problems.

According to Papalia, Wendkos and Duskin (2005), there are three main parenting styles: authoritarian, flexible with authority and permissive. When the adolescent children of migrants were asked about the type of family (parents) they thought they had, 70 percent said flexible with authority, 20 percent said authoritarian, and nine percent said permissive. These data are similar to those obtained from those whose parents are not migrants. The only striking fact is that 16 percent of the latter regard their families as authoritarian, which may indicate the need of the parent who stays at home to assert her authority, which in turn leads her to exercise greater control over the children.

In order to prove a possible relationship or dependence of this aspect on certain sociodemographic characteristics (age and sex) of the participants, the chi square test was administered, which showed that teenagers' opinion of their family type depends on gender (χ2 = 30.200, gl = 2, p < .05). Thus 77.5 percent of females report that their families are flexible, whereas only 67.5 percent of males have this opinion. No statistically significant differences were detected regarding age (χ2 = 11.151, gl = 10, p > .05).

A total of 45.4 percent of teenage children of migrants regard the relationships in their families as fair to poor. As shown in table 4, the data reveal a difference of 12.6 percent percentage points of those compared with those whose parents are non-migrants (32.8 %). In this respect the chi square test shows a significant difference (χ2 = 19.737, gl = 2, p < .05).

Regarding their opinion about their parents' couple relationship, there was also a significant difference (χ2 = 21.465, gl = 2, p < .05), since 48.6 percent of migrants' adolescent children described it as fair to poor, whereas only 37.9 percent of those whose parents have not emigrated share this view (see table 4). At this point, one should consider the absence of either or both parents due to the fact that they have migrated and their influence on the way they relate to each other.

As one can see, for migrants' teenage children, the way they regard their families is directly linked to the opinion they have of their parents' relationship.

Adolescents who experience the absence of one or both of their parents due to migration, reported that household rules are clear, either always (49 %) or sometimes (44 %), and just the seven percent reported a lack of clear family rules. This results are equal to those reported by adolescents whose parents have not emigrated.

Teenagers were asked to rate the extent to which they consider that some family functions are fulfilled in their own families, yielding the following results. Regarding the function associated with the satisfaction of subsistence needs and physical well-being, most participants, who were migrants' children, said that this was achieved, in contrast with what was reported by the children of non-migrants.

In regard to the promotion of the bonds of affection and social union, through which the expression of emotions is taught, teenagers believed that this was achieved in their families, as shown in the table 5.

These data show that the majority of both the children of migrants and non-migrants considered, in most cases, that the function of the expression of affection in the family in which they live is fulfilled to a great extent, in keeping with the findings of specialists in the field (Macias, 1994:143-145).

As for the teachings related to forms of socialization, migrants' children, the majority of whom are adolescents, felt that this was achieved to a certain extent or quite a lot, followed by those who thought that this was achieved to a great extent. At the same time, however, 14.7 percent of them judged this function to be poorly performed and while 5.2 percent declared that it was not achieved at all. In the case of students with non-migrant parents, the highest percentage was located in the categories of quite a lot and a lot (see table 6).

These data reveal the importance of the family in the acquisition and integration of the roles played in society as well as the social integration processes and ways of relating to others within a social organization.

As shown in table 7, in terms of promoting learning and creativity in children, the majority of teenagers reported that this is a function that is achieved to quite a large extent in their families. The data show the disadvantages faced by students with one or both parents absent due to the phenomenon of migration: promoting engagement in school activities declines, which in turn is related to academic performance (shown below in table 10).

One of the greatest acquisitions in the family is the one linked to the axiological structure of its members, as well as the ideology and patterns of the culture in which they are immersed. Teenagers (migrants' children) considered, in most cases, that this function is performed to a great extent in their families, since 43.3 percent are included in the category of "a lot" and 28.8 percent in the category of "quite a lot". In the case of teenagers whose parents have not emigrated, 54.6 percent felt that this task was performed to a great extent (see table 8).

Use of Addictive Substances

In order to address the issue of substance use, teenagers were asked about their use in their families. It is worth mentioning that in 14.3 percent of migrants' children, alcoholism was present and that two percent mentioned the use of another drug (2 % did not answer, and 1 % mentioned another problem unrelated to the purposes of this study). These data are consistent with the situation reported by certain authors such as Pinazo, and Ferrer (2001:108-109), Velasco (2000:55), Vielva (2001:139) regarding the fact that addiction in teenagers is influenced by the consumption of addictive substances by their parents or older siblings as well as by the lack of a warm parent-child relationship, which includes genuine emotional expressions as well as consumption habits and inappropriate models (Vega-Fuente, 1998:19).

Thus, in the data on tobacco, nearly a third of the young children of immigrants (28.5 %) reported having used it at least once while 12.6 percent said that they had done so several times, showing that 41.1 percent have used this substance at least once. Thus, 69.5 percent of students whose parents have not emigrated have not used tobacco, which is a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 18.429, gl = 2, p < .05) (see table 9).

In the case of alcohol use, the data are linked to those reported for the presence of alcoholism in their families: 14.3 percent reported problems of this nature and, as shown in table 8, 52 percent of these teenagers have used this substance at least once in their lives. A statistical analysis revealed significant differences (χ2 = 13.630, gl = 2, p < .05), showing that the non-migration of parents helps keep teenagers away from alcohol.

The data regarding the use of other drugs (it should be noted that, given the age range of the participants in the study, the use of all substances is illegal) found that only 4.6 percent (with migrant parents) reported having used them once while 2.5 percent reported that they had used them on several occasions, showing that 92.9 percent had not used this type of substances. Among students whose parents have not emigrated, this figure is 96.6 percent. Once again, using the χ2 confirmed a significant relationship between substance use tobacco (χ2 = 170.853, gl = 10, p < .05), alcohol (χ2 = 141.482, gl = 10, p < .05) and other drugs (χ2 = 70.888, gl = 10, p < .05) and teenagers' age, showing that age is a factor that significantly influences the consumption of addictive substances.

School Environment

The data show that teenagers believe school can be a factor of development due to the interest shown by teachers towards their students, since they pay special attention to the problems that occur.

In this respect, the majority of the students surveyed declared that their schools were friendly places (53 %), while 37 percent thought that they were authoritarian. Conversely, nine percent of respondents found them indifferent. These views include teenagers' relationships with their teachers and head teachers.

As for teenagers' academic performance, the data indicate that, both for those who have one parent absent due to migration and for those who do not, most have a grade point average of between 7 and 8 (see table 10). However, there is a lower percentage of students with an average of 9 and 10 among the former.

Conclusions

The results indicated that 40 percent of these young people, representing the sum of those with borderline and clinical levels, are at risk, since they display some kind of problem that requires attention. The most frequently identified problem is aggressiveness. The syndromes: introversion and somatization, were observed more frequently in female than male adolescents. Behaviors such as anxiety and introversion appear more frequently among the children of migrant parents than among young people in general.

This underscores the need for prevention and early intervention for young people at risk, an issue that does not seem to have been addressed given the lack of services of this nature for children and youth, since it is in these spaces that the risk factors to which they are exposed could be reduced.

Aggressiveness was one of the behaviors with the highest incidence. These findings corroborates several studies showing this result, which is understandable given the stage of transition at which young people are located, characterized by behaviors such as disobedience, being demanding and rebelliousness, among others, which could become a problem of adaptation at a later age.

Regarding the relationship between gender and syndrome, both introversion and somatization in females occurred almost twice as often in males. One possible explanation suggests that hormonal factors could contribute to the higher frequency of depression symptoms in women, particularly due to the hormonal changes implicit in the menstrual cycle, which might be affecting mood as well as the expression of somatic distress.

The strongest relationship between these variables (family, school and addictions) regarding the expression through behavioral problems among young people proved to be the family, specifically those involving relations between parents and within the family. This suggests the possibility that the fact that a young person has behavioral or school problems may be directly related to poor relations between his or her parents and within the family. This confirms the fact that the family continues to be the most influential factor in young people's behavior.

A good relationship between the members of a couple is important when it comes to agreeing on guidelines for raising children. However, this becomes difficult when one or both parents are absent due to migration. In this respect, the study results show that the father's absence negatively impacted the teenager's relationship with his mother and the rest of the family. In many cases, it is the custom for fathers to establish family rules and in their absence, mothers are forced to assume this responsibility, which is an extremely difficult situation. Another factor that hinders the relationship with the parent who stays behind (usually the mother), is when she seeks employment, in order to contribute to the family upkeep when remittances fail to arrive, a situation that also impacts teenagers' school performance.

The physical and emotional distance between parents and their children leads teenagers to seek acceptance and a sense of belonging to a new group or to escape the emotional state of sadness, loneliness and abandonment that may predispose young people to approach groups addicted to harmful substances such as alcohol, tobacco or drugs. This situation is more likely to occur when there is evidence of relatives with the same addictions.

The characteristics acquired the family when one or more of its members migrate strains relations between parents, turning the absence of one or both into intrafamilial distancing, an adverse situation caused by the lack of communication and new family experiences. Based on the idea of the family as the basis of children's mental health, migration may produce a risky situation in this regard, since it creates a greater likelihood of the expression of emotional and behavioral problems in children.

References

ACHENBACH, Thomas, 2001, "Child Behavior Check List/11-18 Youth Self-Report", Burlington, United States, ASEBA. [ Links ]

AGUILAR-MORALES, Jorge Everardo et al., 2008, "Migración, salud mental y disfunción familiar: Impacto socioemocional en la familia del indígena oaxaqueño migrante", Centro Regional de Investigación en Psicología, vol. 2, no. 1, January, pp. 51-62. [ Links ]

BECOÑA, Elisardo, 2002, Bases científicas de la prevención de las drogodependencias, Madrid, Ministerio del Interior. [ Links ]

BUSTAMANTE, Jorge, 1988, "The Immigrant Worker: A Social Problem or Human Resource", in Armando Ríos Bustamante, ed., Mexican Immigrant Workers in the United States, Los Angeles, Chicano Studies Research Center-UCLA (Anthology Series, no. 2). [ Links ]

CENTROS DE INTEGRACIÓN JUVENIL-SISTEMA DE INFORMACIÓN EPIDEMIOLÃGICA DEL CONSUMO DE DROGAS (CIJ-SIECD), 2010, "Tendencias de consumo de droga. Coordinación regional sur". Available at <http://www.biblioteca.cij.gob.mx/siec2010/sur2.asp?clave=9110> (last accessed on April 15, 2012). [ Links ]

CHANEY, Elsa, 1985, "Women who Go and Women who Stay Behind", in Migration Today, no. 10, pp. 7-13. Available at <http://www.bibliojuridica.org/libros/1/357/8.pdf> (last accessed on June 16, 2008). [ Links ]

FALICOV, Celia, 2007, "La familia transnacional: Un nuevo y valiente tipo de familia", Perspectivas sistémicas. La nueva comunicación, no. 94/5. Available at <http://www.redsistemica.com.ar/articulo94-3.htm> (last accessed on April 15, 2012). [ Links ]

FARRINGTON, David P., 1989, "Early Predictors of Adolescent Aggression and Adult Violence", Violence and Victims, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 80. [ Links ]

GARDUÑO, Silvia, 2008, "Separa migración a madres de hijos", Reforma, in "Nacional" section, May 10. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ, María del Pilar [tesis doctoral], 2007, "Los valores en la televisión y su incidencia en los adolescentes de Xalapa-México como protectores del uso de sustancias adictivas", Madrid, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. [ Links ]

JONES, Deborah et al., 2002, "Psychosocial Adjustment of African-American Children in Single-Mother Families: A Test of Three Risk Models", Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 64, no. 1, February, pp. 105-115. [ Links ]

MACÍAS AVILÉS, Raymundo, 1994, "¿Cómo hacer que un matrimonio dure para toda la vida?", Familia y verdad: Memorias del XIX Congreso para la Familia, México, Instituto Juan Pablo II, pp. 139-155. [ Links ]

MESTRIES BENQUET, Francis, 2003, "Crisis cafetalera y migración internacional en Veracruz", Migraciones Internacionales 5, Tijuana, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, vol. 2, no. 2, July-December, pp. 121-148. [ Links ]

MORADILLO, Fabián, 2002, Adolescentes, drogas y valores. Materiales educativos para la escuela y el tiempo libre, Madrid, CCS. [ Links ]

MORALES, Roberto, 2004, "Niños de 10 años drogadictos", Diario de Xalapa, in "1A" section, p. 1, January 31. [ Links ]

MOYA, José, and Mónica URIBE, 2007, "Migración y salud en México: Una aproximación a las perspectivas de investigación; 1996-2006", Pan-American Health Organization. Available at <http://www.mappingmigration.com/pdfs/migracionsaludmex.pdf> (last accessed on March 13, 2012). [ Links ]

MUMMERT FULMER, Gail R., 2003, "Del metate al despate: Trabajo asalariado y renegociación de espacios y relaciones de género", in Heather Fowler-Salamini, and Mary Kay Vaughan, eds., Mujeres del campo mexicano, 1850-1990, México, El Colegio de Michoacán/Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades-Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, pp. 295-322. [ Links ]

PAPAIA, Diane; Sally WENDKOS OLDS, and Ruth DUSKIN, 2005, Desarrollo humano, 9th ed., México, McGraw-Hill Interamericana de México. [ Links ]

PIERRI, Raúl, 2006, "Infancia-América Latina: La vulnerabilidad no emigra", Inter Press Service. Available at <http://ipsnoticias.net/nota.asp?idnews=38971> (last accessed on June 28, 2010). [ Links ]

PINAZO, Sacramento, and Xavier FERRER, 2001, "Factores familiares de riesgo y de protección del consumo de drogas en adolescentes", in Santiago Yubero, coord., Drogas y drogadicción. Un enfoque social y preventivo, Cuenca, Spain, Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, pp. 107-140. [ Links ]

QUESNEL, André, and Alberto del Rey [paper], 2003, "Movilidad, ausencia y relaciones intergeneracionales en Veracruz, México", in International Congress on "Movilidad y Construcción de los Territorios de la Multiculturalidad", Saltillo, México, Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, March 31-April 3. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Manuel, 2000, Familia y política social, Buenos Aires, Lumen/Hvmanitas. [ Links ]

ROUSE, Roger, 1991, "Mexican Migration and the Social Space of Postmodernism", Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, Madrid, vol. 1, no. 1, Spring. [ Links ]

SALGADO DE SNYDER, Nelly, 1994, "Mexican Women, Mental Health and Migration: Those who Stay Behind", in Robert G. Malgady, and Orlando Rodríguez, eds., Theoretical and Conceptual Issues in Hispanic Mental Health Research, Melbourne, Australia, Krieger Publishing Company, pp. 113-139. [ Links ]

SALGADO DE SNYDER, Nelly, 1996, "Problemas psicosociales de la migración internacional", Salud Mental, vol. 19, supplement 1, April, pp. 53-59. [ Links ]

SALGADO DE SNYDER, Nelly, and Margarita MALDONADO, 1993, "Funcionamiento psicosocial en esposas de migrantes mexicanos a los Estados Unidos", Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, vol. 2, no. 25, pp. 167-180. [ Links ]

SARASON, Irving G., and Bárbara R. SARASON, 2006, Psicopatologia. Psicología anormal: El problema de la conducta inadaptada, 11a ed., México, Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

SECRETARÍA DE SALUD-DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE EPIDEMIOLOGÍA (DGE), 2003, "Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de las Adicciones (Sisvea). Informe 2003", Subsecretaría de Prevención y Promoción de la Salud. Available at <http://www.epidemiologia.salud.gob.mx/doctos/infoepid/inf_sisvea/informes_sisvea_2003.pdf> (last accessed on November 16, 2005). [ Links ]

TATTUM, Delwyn P., and David A. LANE, 1989, "Bullying in Schools", London, Trentheam Books, p. 64. [ Links ]

TRIANES, María Victoria, 2000, La violencia en contextos escolares, Archidona, Spain, Ediciones Aljibe, pp. 81-87. [ Links ]

TUIRAN, Rodolfo, 2001, "Estructura familiar y trayectorias de vida en México", in Cristina Gómez, ed., Procesos sociales, población y familia: Alternativas teóricas y empíricas en las investigaciones sobre vida doméstica, México, Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

VEGA-FUENTE, Amando, 1998, "Comunicación social: Entre la publicidad y el espectáculo", Comunicar, no. 10, pp. 2-20. Available at <http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=15801003> (last accessed on May 2, 2009). [ Links ]

VELASCO, Rafael, 2000, La familia ante las drogas, México, Trillas. [ Links ]

VIELVA, Isabel, 2001, "La disciplina y las prácticas educativas", in Isabel Vielva, Luis Pantoja, and Juan Abeijón, Las familias y sus adolescentes ante las drogas. El funcionamiento de la familia con hijos adolescentes (consumidores y no consumidores de drogas) de comportamiento no problemático. Avances en drogodependencias, Bilbao, Universidad de Deusto. [ Links ]

VILLATORO, Jorge Ameth, and María Elena MEDINA-MORA ICAZA, 2002, "Las encuestas con estudiantes. Una población protegida en constante riesgo", Observatorio mexicano en tabaco, alcohol y otras drogas 2002, México, D. F., Comisión Nacional contra las Adicciones-Secretaría de Salud, pp. 125-127 (Observatorio, no. 4). Available at <http://www.conadic.gob.mx/redir.asp?link=doctos/observatorio_2002/obs_index.htm> (last accessed on November 11, 2005). [ Links ]

WADE, Terrance; John CAIRNEY, and David PEVALIN, 2002, "Emergence of Gender Differences in Depression during Adolescence: National Panel Results from Three Countries", Journal of American Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 41, no. 2, February, pp. 190-198. [ Links ]

WHITNEY, Irene, and Peter K. SMITH, 1993, "A Survey of the Nature and Extent of Bullying in Junior/Middle and Secondary Schools", National Foundation for Educational Research, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 3-25. [ Links ]

WOLFF, Jennifer C., and Thomas H. OLLENDICK, 2006, "The Comorbidity of Conduct Problems and Depression in Childhood and Adolescence", Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, vol. 9, no. 3-4, December, pp. 201-220. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO), 2003, Investing in Mental Health, Geneva, World Health Organization. Available at <http://www.who.int/mental_health/en/investing_in_mnh_final.pdf> (last accessed on June 28, 2011). [ Links ]

YARCE, Jorge, 2004, Valor para vivir los valores: Cómo formar a los hijos con un sólido sentido ético, Barcelona, Belacqva. [ Links ]

YEDRA, Luis Rey, and María del Pilar GONZÁLEZ, 2002, "Desarrollo humano familiar: Un modelo centrado en la persona", Psicología Iberoamericana, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 25-33. [ Links ]

* Text originally written in Spanish.

INFORMACIÓN SOBRE LAS AUTORAS

LAURA OLIVA ZÁRATE: es doctora por la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED, España) -con distinción cum laude-, maestra en psicoterapia infantil gestalt y licenciada en psicología. Es investigadora en el Instituto de Psicología de la Universidad Veracruzana (UV, México); docente de la Maestría en Desarrollo Humano y de la Especialización en Estudios de Opinión, Imagen y Mercado de la UV y pertenece al Cuerpo Académico "Psicología y Desarrollo Humano" de la misma universidad. Es miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores y posee perfil Promep. Cuenta con más de 50 artículos y tres libros sobre el estudio de la agresión y la violencia, así como de los problemas de conducta en infantes y adolescentes, entre los que destaca el artículo en coautoría con María Luisa Hernández y Claudio Rafael Castro, "Más que palabras nos dicen los adolescentes que desean migrar. Estudio estadístico de las respuestas a una pregunta abierta", en Revista de Psicología Social Aplicada (2a. etapa, vol. 1, núm. 1, 2012), y el libro en coautoría con María Luisa Sevillano, Relación entre la televisión y la manifestación en problemas conductuales en niños preescolares (Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 2007). Dirección electrónica: loliva@uv.mx.

LUIS REY YEDRA: es doctor en orientación y desarrollo humano y posdoctorado en el ámbito del Centro de Investigação em Psicologia de la Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa. Es maestro en desarrollo humano por la Universidad Iberoamericana (México, D. F.) y licenciado en psicología por la Universidad Veracruzana (UV, México). Es docente e investigador en la Facultad de Pedagogía y en la Maestría en Desarrollo Humano -de la cual fue fundador- del Instituto de Psicología y Educación de la UV. Posee perfil Promep y es miembro del Cuerpo Académico "Psicología y Desarrollo Humano" de la misma universidad. Ha publicado más de 30 artículos en revistas científicas; es coautor de cuatro libros y de capítulos de libros sobre desarrollo humano, familia, adolescentes, factores protectores de adicciones, incidencia de la televisión en el uso de drogas, y violencia en el noviazgo. Entre sus publicaciones más recientes se encuentran, en coautoría con María del Pilar González Flores: "La influencia de la familia en la manifestación de la violencia en las relaciones de noviazgo en universitarios", en Psique. Anais - Série Psicologia (vol. VII, 2011), y "La influencia de la televisión para el consumo de drogas: La visión de los adolescentes", en De la salud a la enfermedad. Hábitos tóxicos y alimenticios (UANL, 2009). Dirección electrónica: lyedra@uv.mx.

MARÍA DEL PILAR GONZÁLEZ FLORES: es doctora en educación por la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED, Madrid) y posdoctorada en el ámbito del Centro de Investigação em Psicologia de la Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa. Maestra en orientación y desarrollo humano por la Universidad Iberoamericana (México, D. F.) y licenciada en psicología por la Universidad Veracruzana (UV, México). Fundadora y profesora-investigadora de la Maestría en Desarrollo Humano del Instituto de Psicología y Educación y en la Facultad de Pedagogía de la UV. Posee perfil Promep. Es miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores y del Cuerpo Académico "Psicología y Desarrollo Humano" de la misma universidad. Ha publicado más de 30 artículos en revistas científicas y es coautora de cuatro libros y de diversos capítulos de libros. Sus temas de investigación son: desarrollo humano, familia, adolescentes, factores protectores de adicciones, incidencia de la televisión en el uso de drogas, y violencia en el noviazgo. Ha participado en diversos foros nacionales e internacionales. Entre sus publicaciones recientes destacan los artículos en coautoría: "Presencia de violencia en el noviazgo en estudiantes de una universidad portuguesa", en Psique. Anais - Serie Psicología (vol. VIII, 2012) y "Las relaciones familiares y el consumo de drogas en los adolescentes de Xalapa, Veracruz", en Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala (vol. 12, núm. 1, 2009). Dirección electrónica: pgonzalez@uv.mx.

DINORAH LEÓN CÓRDOBA: es licenciada en psicología por la Universidad Veracruzana (UV, México), maestra en psicoterapia gestalt. Es investigadora de tiempo completo en el Instituto de Psicología y Educación, y docente de la Licenciatura en Pedagogía y la Maestría en Desarrollo Humano en la Unidad de Enseñanza Abierta de la UV. Es miembro del Cuerpo Académico "Psicología y Desarrollo Humano" en la LGAC "Análisis y diseño de interacciones sociales e institucionales" de la misma universidad. Sus investigaciones han sido publicadas en revistas especializadas en el área de la salud. Entre las más recientes se encuentran los artículos en coautoría: "Factores de riesgo para el exceso de peso infantil", en Medicina Salud y Sociedad. Revista Electrónica (vol. 2, núm. 2, 2012); "Evaluación de consistencia interna y en el tiempo de una escala para identificar factores asociados al exceso de peso", en IPyE: Psicología y Educación (vol. 5, núm. 10, 2011). Dirección electrónica: dleon@uv.mx.

ELSA ANGÉLICA RIVERA VARGAS: es maestra en desarrollo humano por la Universidad Veracruzana (UV, México), licenciada en educación preescolar por la Escuela Normal Veracruzana Enrique C. Rébsamen (México) y en pedagogía por la UV. Es investigadora en el Instituto de Psicología y Educación, y docente de la Licenciatura en Pedagogía y la Maestría en Desarrollo Humano en la Unidad de Enseñanza Abierta de la UV. Es miembro del Cuerpo Académico "Psicología y Desarrollo Humano" en la LGAC "Análisis y diseño de interacciones sociales e institucionales" de la misma universidad. Ha participado en congresos nacionales e internacionales y sus publicaciones abordan la temática de las ciencias sociales. Entre las más recientes se encuentran: (en coautoría) "Violencia escolar en la universidad", en Extensión, divulgación y discusión de experiencias, métodos, tecnologías y propuestas teóricas referidas a la extensión universitaria (vol. 1, núm. 3, 2013); "Factores de riesgo para el exceso de peso infantil", en Medicina, Salud y Sociedad. Revista Electrónica (vol. 2, núm. 2, 2012). Dirección electrónica: erivera@uv.mx.