Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.7 no.2 Tijuana jul./dic. 2013

Artículos

Managing Uncertainty: Immigration Policies in Spain during Economic Recession (2008-2011)

Gestionando la incertidumbre: Las políticas de inmigración en España durante la recesión económica (2008-2011)

Ana López-Sala

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

Date of receipt: May 21, 2012.

Date of acceptance: January 22, 2013.

Abstract

The global economic crisis has changed the landscape of immigration dynamics and migration policies management in Spain, introducing a new immigration order. In this new context, the instruments used to manage migration have been reinvented and readapted to meet the objectives of an immigration policy that has radically changed. The aim of this article is to analyze how the current crisis has affected labor migration flows to Spain and how they are managed and governed. The focus is on changes in policies between 2008 and 2011. There has been a shift from a policy whose principal objective was to recruit workers to meet the demands of the labor market to a policy that focuses on improving the "employ-ability" of unemployed resident immigrants, the promotion of pay-to-go programs and the maintenance of social and economic integration policies.

Keywords: immigration, migration policies, economic recession, migrant worker recruitment, Spain.

Resumen

La crisis económica ha cambiado el panorama de las dinámicas y las políticas migratorias en España y ha introducido un nuevo orden. En este nuevo contexto, muchos de los instrumentos empleados en la gestión migratoria han sido reinventados y readaptados para cumplir con los requerimientos de una política que ha cambiado de forma radical en sus objetivos. El propósito de este artículo es analizar los efectos de la crisis económica en los flujos migratorios de trabajadores hacia España y las transformaciones en su gestión entre los años 2008 y 2011. A lo largo de este período se observa un tránsito desde las políticas de reclutamiento de trabajadores hasta las medidas de mejora de la empleabilidad de los migrantes residentes en situación de desempleo, la promoción del retorno y el mantenimiento de las estrategias de integración social y económica.

Palabras clave: inmigración, políticas migratorias, crisis económica, reclutamiento de trabajadores migrantes, España.

Introduction: A New Migratory Order?

From the mid-1990s the Spanish economy grew rapidly and steadily for a decade. This economic boom increased and consolidated the arrival of foreign workers in the country, their incorporation into the Spanish labor market and the rapid transformation of Spanish society in terms of ethnic, national and religious diversity. The Spanish model of economic development has largely focussed on specific economic sectors such as hospitality and tourism, services, intensive agriculture and construction. This economic context has shaped immigration in Spain, leading to a migratory model based mainly on immigrants seeking work, although there is a component of family and retirement migration. Moreover, the traditionally strong presence of the informal economy, along with low labor regulation, has created a dual labor market and an increasingly irregular foreign labor force in certain sectors.

Three demographic dynamics can also be seen as indirect drivers of these migratory changes due to their effect on the labor market. First, in Spain both the active population and the population in general have been aging due to a sharp fall in birth rates. Second, the population has limited internal mobility and is irregularly distributed throughout the different regions of the country. Lastly, the demand for domestic services has grown as a result of the increased educational attainment of Spanish women and their massive incorporation into the labor market.

Over the past few decades, Spanish immigration policy has broadened its objectives and become more complex, incorporating new and innovative measures to regulate migration and developing a comprehensive integration policy. In the 1990s, the policy was reactive and ambivalent, allowing informal access to the territory despite the measures established by law. For this reason the Spanish immigration model of that period was defined as a model of "tolerated irregularity" (Izquierdo, 2008). Weak internal control and easy access to the labor market stabilized the presence of migrants in the country and eventually led to the formal legalization of their residence. Amnesties for clandestine workers, which occurred periodically after 1986 under the auspices of both left- and right-wing governments, enabled one and a half million people to legalize their status. The integration of immigrants into the receiving country was guaranteed through a system of universal inclusion that included access to social services, allowing minors to be enrolled in schools and providing immigrants with the right to healthcare. This process, which involved the active participation of different levels of government because the decentralized Spanish political system distributes competences among them, required political agreements in order to be carried out (De Lucas, and Díaz, 2006; De Lucas, and Solanes, 2009; López-Sala, 2007).

Throughout the last decade, and particularly since 2004, Spanish policy became increasingly proactive, providing the fight against irregular immigration and border control with more efficient, accurate mechanisms for estimating labor needs and providing access to the Spanish labor market. New instruments have been implemented to regulate migration, such as hiring workers in their country of origin, the Special Catalog of Vacant Jobs and a reform of the Quota Policy. All this was carried out through growing collaboration and coordination between institutions at different levels of government and agreements with the countries from which these migratory flows originate. Integration policy has been improved from the partial measures taken in the past to include integrated, mainstreaming actions that favor the participation of migrants and social equality (Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales, 2007).

The global economic crisis has changed the landscape of immigration dynamics and migration management in the Spanish case, introducing a new immigration order, both in the dynamics of the flows and the political response to them (López-Sala, and Ferrero, 2009; Ferrero, and López-Sala, 2010). The recession and severe job losses have had serious social repercussions within the country and a heavy impact on immigrant workers. The new migration dynamics include an increase in the outflow of both native and foreign workers, some voluntary returns and the containment of inflows. According to estimates recently published by the National Statistics Institute—Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE)—, there will be negative net migration in Spain during this entire decade.1

In this new context, the instruments used to manage migration have been reinvented and readapted to meet the objectives of an immigration policy that has radically changed. Since the demand for workers from outside the country has virtually disappeared, mechanisms have been put in place to improve the "employability" of foreign workers already settled in the country in order to reinsert them into the labor market and ensure decent living conditions, while promoting voluntary return to their countries of origin.

The aim of this paper is to analyze how the current crisis has affected labor migration flows to Spain and how they are managed and governed, as well as the challenges and paradoxes government and society face in this new plural, multiethnic country in conditions of recession. The focus will be on new developments and changes in regulation, control and immigration policies between 2008 and 2011.2

The Unique Nature of Migrations to Spain over the Last Decade: Diverse and Intense Migratory Flows in a Decade of Strong Economic Growth

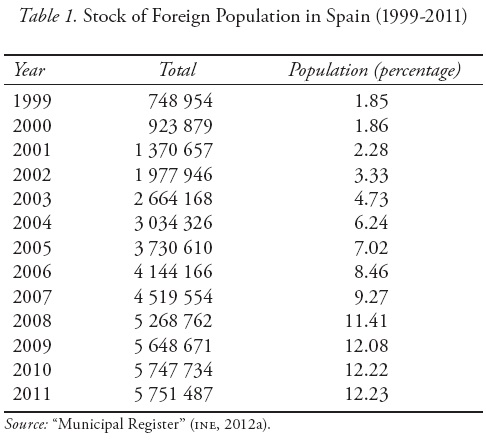

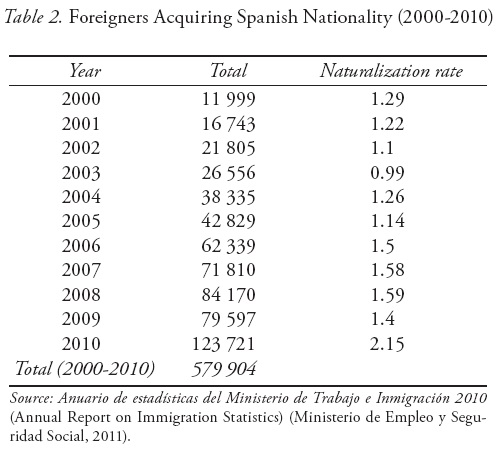

The dynamics of migration to Spain during the past decade have been distinguished by two traits: the intensity and diversity of the flows. Statistics reveal that immigration flows to Spain were extremely intense between 1999 and 2008. In 1999, there were fewer than 750 000 foreign residents in Spain, representing only 1.85 percent of the population, but by 2011 there were over 5.7 million immigrants (see graph 1), which constitutes 12.2 percent of the population (see table 1). However, this number does not truly reflect the intensity of the flow, which is even greater if one considers that over half a million immigrants acquired Spanish nationality during the past decade (see table 2).

The high number of foreigners that have acquired Spanish nationality is the result of a naturalization policy that allows dual citizenship for immigrants from Latin American countries after only two years' residence. However, immigrants from other regions are required to reside in the country for ten years in order to apply for citizenship. This explains the differences in naturalization rates between different groups. In this respect, Spanish naturalization policy is somewhat selective and favors the naturalization of Latin-American citizens.

The immigrant population grew rapidly from the second half of the 1990s onwards, this growth being particularly intense between 2000 and 2003 and again in 2005 and 2006 (see graph 2). In just one decade, between 2000 and 2010, over six million immigrants arrived in Spain.

For several years, Spain became the most important destination country in Europe in absolute and relative terms and the third in absolute terms after the United States and the Russian Federation (Arango, Aja, and Oliver, 2011). The intensity of migration was the result of a combination of several factors. The first factor was economic growth, particularly job creation, between 2000 and 2008, concentrated in unskilled positions in weakly regulated sectors that are unappealing to Spanish workers. Additionally, the demand for domestic services grew as a result of the increased educational attainment of Spanish women and their massive incorporation into the labor market, as well as population ageing and the reproductive cycle of baby-boomers (Fernández-Cordón, 2001).

These intense flows were also highly diverse in terms of where they originated, as reflected in the current migrant stock, which also reveals the changes in arrivals and settlement over the past decade. Migrations to Spain have combined labor and family-based flows with retiree migration. During the 1990s, the most numerous and steadiest flow of immigrants came from Morocco, one of the main sources of migration to Spain. At the end of the 1990s, flows from Latin America increased, especially from the Andes region (Ecuador and Columbia), and were notable during the first half of the past decade. During the second half of the decade, new flows came from Eastern Europe, especially Romania, a flow that has been so intense that Romanians are now the largest immigrant group in Spain.

The latest available data indicate that the largest group of foreigners in Spain are Romanian (913 405). Among the remaining eu member states, the largest groups were British (246 533), Italian (189 841) and Bulgarian (176 333). For non-EU countries Moroccans comprised the largest group (859 105), followed by Ecuadorians (391 231), Colombians (271 596), Chinese (176 335) and Bolivians (157 132). The most recent flows originate from a wide range of countries that include Ukraine, Paraguay, Brazil, and Pakistan. The current foreign population is therefore composed of an even distribution between Latin Americans, Europeans and Africans.

The economic crisis was immediately reflected in the demographic dynamics of migrations to Spain. After 2008, the number of arrivals dropped significantly to levels that occurred at the end of the 1990s. However, despite the severity of the crisis, over the past four years, over 300 000 immigrants have continued to arrive annually. These sustained flows can be explained by a combination of factors, such as continued family reunification, as evidenced by the number of visas given for this reason to non eu citizens and the increase in the number of student visas. However, the overall decrease in arrivals has combined with acceleration in departures, which include different forms of geographic mobility, including re-emigration and returns to the country of origin,3 resulting in a net migration that is still positive but by much less so than it has been over the past few years. Consequently, the foreign population in Spain has only grown moderately since 2008. Increased emigration of Spanish nationals is the last aspect of the transformation caused by the economic crisis. According to "The Residential Variation Statistics (rvs)", over 37 000 Spanish nationals emigrated in 2010 (INE, 2012b). Between January and September 2011, this number exceeded 50 000. The number of Spaniards leaving the country rose by 44 percent during the first six months of 2012 compared with the same period in 2011. The registers do not distinguish between emigrants born in Spain and those that became naturalized citizens, so it is possible that some of these departures include immigrants who had acquired Spanish nationality and are returning, whether temporarily or permanently, to their countries of origin.

Immigrants and the Spanish Labor Market

Throughout the past decade, immigrants were incorporated into the Spanish regular and irregular labor market due to market demands. As mentioned earlier, the bulk of this migratory flow was attracted by the opportunities offered by an expanding labor market base in sectors such as tourism, construction and services. Spanish economic growth led to a model based on a high level of temporary work in low productivity jobs. The Spanish baby-boomers were often overqualified to fill the enormous need for unskilled workers that the booming economy required. Between 2000 and 2008 almost five million new jobs were created, just under a third of all the new jobs created in the entire European Union during this period. Approximately half these positions were filled by foreign workers (Izquierdo, 2011). The stock of foreign workers increased from 454 571 in 2001 to 1 840 827 in 2010 reaching its highest point in 2007 (see graph 4).

Throughout the last decade, one of the most significant changes in the Spanish labor market has been the steady increase of foreigners among the active population. Immigrants have come to represent 16 percent of the active population, a higher percentage than in the majority of traditional immigration countries. In 2009, the percentage of foreigners in the active population was lower in Austria (10.9 %), Germany (9.1 %), Belgium (8.7 %), the United Kingdom (8 °%) and France (5.6 °/o), with only Cyprus, Luxemburg and Switzerland experiencing higher percentages (Elias, 2011).

Unlike in Northern and Central Europe, not only do immigrants in Spain account for a large part of the active population, but they also have higher rates of activity than the native population (Cachón, 2009). In 1996 the percentage of the active population not comprising nationals of an eu member state was 0.7 percent, barely over 100 000 workers. This data is in sharp contrast with those available for the middle of the past decade: almost 2 000 000 foreign workers from outside the eu were incorporated into the active population, accounting for 9.3 percent of all workers in Spain.

In 2005, immigrants had a global activity rate of 78.9 percent, almost 24 points higher than that of Spaniards (55.2 %). And as Cachón has pointed out, this difference in global activity was not a random occurrence in the middle of the decade, but rather a persistent tendency, albeit variable over time. This persistence is clearly seen in the "Economically Active Population Survey" (EAPS)4 conducted from 1996 to the end of the decade (Cachón, 2009). By late 2010, the activity rate of immigrants was 76 and 57 percent in the case of natives. However, it should be noted that this can largely be accounted for by the younger average age of foreigners (Ferrero, and López-Sala, 2010).

The percentage of immigrants working in industry and services has remained stable throughout the decade. Conversely, employment in agriculture and construction has been more irregular, depending on changing economic dynamics. The recent economic crisis explains, for instance, the shift in employment from construction to agriculture and services (see table 3). A shift can also be observed in the economic areas in which foreign workers are registered in the social security system. Although over 278 000 dropped out of the system between 2008 and 2011, the number of foreign workers engaged in agriculture and domestic work actually increased, indicating that these sectors have become "havens" during the economic crisis.

The debate on the effect of migrant workers on the labor market has not been as heated as in other European countries, and public opinion surveys do not reveal high levels of xenophobia (Godenau et al., 2012). Nationals fear competition from migrant workers, especially in sectors such as domestic service, hospitality and tourism. On the other hand, there was a high demand for labor that was not met by native workers. However, the issue regarding competition has recently been raised as a consequence of the severe economic crisis in Spain (Cea, and Valles, 2011).

The economic crisis has also had an effect on remittances. According to data provided by the Bank of Spain in its statistical bulletins (Bank of Spain, 2012), the amount of money remitted from Spain has fallen significantly since the middle of 2008, the year when the largest amount was sent: 8.55 billion euros. The principle destinations were Colombia, Morocco and Ecuador. However, between 2008 and 2010, remittances dropped by over 20 percent. The largest drops occurred in flows to Ecuador, Romania and the Dominican Republic in 2008 and to Brazil, Morocco and Senegal in 2009. During 2011, there was a slight recovery, despite the negative economic cycle, but in 2012 remittances dropped again by over 14 percent.

Managing Migration during Recession

Controlling Flows and Borders

Since 2006, the establishment and enhancement of migratory flow control policies have limited unauthorized access to the country. Moreover, the economic crisis has diminished Spain's appeal as a destination for migratory flows. This explains why migration control policies have not significantly changed over the past four years and, instead, initiatives are focusing more on developing European policy on external borders. The objectives of fighting irregular immigration and improving surveillance and identification have been maintained, especially via the use of new biometric technology and database development.

The effectiveness of the mechanisms implemented since the beginning of the past decade, especially after the intensification of irregular migration arriving on boats in 2006, along with the drop in demand for workers due to the economic crisis, has limited the number of unauthorized arrivals at Spanish borders (López-Sala, and Esteban, 2010; López-Sala, 2012). In this respect, the decrease in number of detentions at external borders can be explained by both the measures implemented and the struggling economy (see graph 5).

During this period, the fight against irregular immigration has been consolidated as a feature of Spanish security policy. Initiatives designed to improve the technological aspect of border control have therefore been accompanied by an increase in human resources. For example, the number of border police grew by 60 percent from 10 239 to 16 375 between 2003 and 2010. Another two initiatives have been the enhancement of relations with the countries of origin, which has enabled joint surveillance of migratory flows in transit and the improvement of expulsion procedures. The lower number of arrivals has created a drop in the number of expulsions carried out since 2007 (see table 4). However, although the overall number of expulsions has decreased, the number of qualified expulsions5 has increased, accounting for 70 percent of the expulsions performed in 2010.

NeverthelessJdespite the fact that the effects of the crisis are noticeable in other policy areas, it cannot be said that the economic crisis has had a significant effect on Spanish border policy. In general terms, over the past few years the focus of migration control has shifted from controlling the border to internal control.

In the area of internal control, changes have involved an increase in the number of work inspections—not only directed at foreign workers, but also at nationals—and in the number of "qualified expulsions", as already mentioned, which increased by 50 percent from 5 564 to 8 196 between 2008 and 2010.

In 2009 the largest police union—Sindicato Unificado de Policía (SUP)—criticized the instructions issued by the Ministry of the Interior to conduct police controls to identify irregular immigrants (sup, 2009). This aspect was criticized again by the police and NGOs in 2010 and 2011, but former Minister of the Interior, Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba, has repeatedly denied that police sweeps are being carried out to identify undocumented immigrants, adding that police controls occur for security reasons rather than as part of migration policy.

The international reaction to increased police control of irregular immigrants and the use of ethnic profiling was revealed in a report by the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination published in February 2011, urging the Spanish government to avoid arrests based on ethnic profiling (un, 2011). The same recommendation was submitted in 2011 by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, calling for Spain to ensure "an effective prohibition of ethnic profiling practices by its police forces, noting that they reinforce prejudice and stereotypes against certain ethnic groups and legitimize racial discrimination against these vulnerable groups".

The fight against irregular immigration, as an objective of security policy linked to organized crime, has led to the improvement of mechanisms to fight against forged documents and migrant smuggling networks and human trafficking. For instance, in 2006 the Spanish police created the Immigration Networks and Document Forgeries Unit—Unidad Central de Redes de Inmigración Ilegal y Falsedades Documentales (UCRIF)—, which operates both within Spanish territory and at the border. The fact that security has become a key variable in the development of Spanish political action has affected initiatives in the fight against organized crime and human trafficking. These changes have not been linked to the economic crisis, but rather to the growing importance of different kinds of human mobility within the security agenda. The European Security Strategy (ESS), approved in 2003, includes organized crime as a new threat related to aspects such as cross-border trafficking of illegal migrants (EUISS, 2003). Similarly, uncontrolled migratory flows are also identified as risks and threats to Spanish security in the recently-approved Spanish security agenda (Arteaga, 2011).

Also notable are the legal and institutional changes undertaken to fight against the trafficking of women and protect them. Between 2006 and 2009, the Spanish government approved the plan against trafficking and ratified the Council of Europe's (2005) Convention on Action against trafficking in Human Beings. The Aliens Law in 2009 created a framework to promote measures to identify and protect victims, as well as to ensure coordination between institutions (Gobierno de España, 2011). Moreover, at the end of 2010, a new penal code came into force in which article 177 introduces the crime of trafficking in human beings as a crime for the first time in Spanish law.

Recruiting Immigrant Workers during Recession? From Recruitment to Protection and "Employability"

The economic crisis has had a significant impact not only on migratory flows, which have dramatically decreased, but also on Spanish immigration policy. The mechanisms developed throughout the past decade, particularly since 2004, a period of high demand for workers, have been maintained, but been greatly reduced or paralyzed.

Many of the procedures designed and approved before the economic crisis are flexible and can be adapted to the transformations in labor demand and the economic climate. For example, since 2008 there has been a dramatic reduction in the number of jobs offered through the Quota System and the Special Catalog of Vacant Jobs8 and also in the number of workers in bilateral programs to recruit in their countries of origin. The number of jobs offered through the Quota System decreased from 27 034 in 2007 to 168 in 2010, while the jobs in the Catalog have progressively decreased to an extremely limited number of occupations, fewer than twenty, the majority of which are medium to highly skilled. In addition, " job search" visas have been eliminated (Arango, Aja, and Oliver, 2011; Rojo, and Camas, 2010; Cebolla, Ferrero, and López-Sala, 2012).

The economic crisis coupled with high unemployment levels have also sharply restricted the hiring of workers from abroad and the number of permanent workers. Whereas in 2011 hiring in origin included temporary and permanent highly-skilled jobs, in 2012 the only hiring in origin foreseen was seasonal work in agriculture and services.

Other important initiatives implemented in the field of immigration management and labor market regulation have been the improvement of the "employability" of resident immigrants receiving unemployment benefits and the promotion of geographic and sectorial mobility through immigration regulation reform (Gobierno de España, 2009). In order to facilitate job seeking in Spain, work authorizations have been modified to eliminate geographic or activity restrictions and to allow foreign workers to transition between employment and self-employment. This mobility was not possible for foreigners under the previous legislation. These legal amendments will make it easier for foreign workers to work in different parts of Spain and change their economic activity.

The latest reform of the Aliens Law (Gobierno de España, 2011) also included transformations in the regulation of how foreign workers gain entry into the Spanish labor market in this new economic climate. First of all, the reform allows reunified family members (children over 16 and spouses) access to employment. This allows the number of active members in immigrant families to increase, which is essential for families trying to cope with the economic crisis by diversifying their sources of income. Other less important modifications were implemented not in response to the crisis, but rather as a result of the transposition of European norms (a work permit for highly skilled immigrants, known as the blue card) and the increased competences of certain Spanish autonomous communities in their local labor markets which were written into their new autonomy statutes.

Lastly, at the end of 2011, the reactivation of the transition period for the free movement of Romanian workers in Spain was approved. This measure, supported by the European Commission, only targets new workers, that is, Romanian citizens who have not previously worked in Spain. It is an exceptional measure, however, that will be in force until the end of 2013 and depending on the national employment situation, will either be maintained or discontinued at the end of the transition period.

Pay-to-Go Programs

The severe economic crisis affecting Spain since 2008 has led to the design and implementation of return programs. However, Spain already has had experience in the development of these programs: immigrants returning home, especially to develop their country of origin, have been a part of the Spanish migration agenda since the beginning of the past decade. There are a total of three voluntary return programs that have been developed by the central administration in Spain and some programs have also been implemented by autonomous communities.

The first pay-to-go program in Spain was launched in 2003 and is known as the Voluntary Return Program for Immigrants from Spain—Programa de Retorno Voluntario de Inmigrantes desde España (Previe)—(OIM, 2003). This program is designed for non-EU immigrants without resources who have been living in a precarious social situation in Spain for at least six months and includes irregular and regular immigrants, asylum seekers or other vulnerable groups. Since 2003 over 14 000 people have taken advantage of this program and the number of applicants increased significantly in 2008, 2009 and 2010 coinciding with the economic crisis (see graph 6). Almost 60 percent of the new returns included in this program occurred since 2008 while 2009 saw the highest number of immigrants taking advantage of this program.

Applicants are primarily Bolivians, Argentineans, Brazilians and to a lesser extent Ecuadorians. Immigrants that take part in this program have their return flight to their city of origin paid for and are given a grant to help cover the initial cost of resettling in their country of origin. This program has been developed by iom and other ngos on behalf of the Spanish government.

In 2008 the main voluntary return program stemming from the economic crisis was approved as part of the active initiatives in migration policy during the recession: the Early Payment of Complementary Unemployment and Resettlement Benefits to Foreigners Voluntarily Returning to their Countries of Origin Program—or APRE—(Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social, 2008). This program is directed at nationals from third countries, legal residents in Spain who are currently unemployed from countries with which Spain has bilateral agreements regarding social security benefits.9 The program allows beneficiaries, who must be registered with employment offices, to receive lump payments for any accumulated unemployment benefits.

In addition to returning to their country of origin, migrants are not allowed to return to Spain to reside or carry out a lucrative or professional activity, either as independent or contracted workers, for a period of three years. Unemployment benefits are received in two payments: 40 percent is paid in Spain and the remaining 60 percent is paid in the country of origin a minimum of 30 days after the first payment, with a maximum period of 90 days. In order to receive the second payment, beneficiaries must go to the Spanish consulate or a diplomatic representative in their country of origin. Official estimates indicate that approximately 130 000 people meet these requirements and can potentially benefit from this program. The main nationalities of these potential beneficiaries are, in descending, Morocco, Ecuador, Columbia, Peru, Argentina and Ukraine.

The latest data provided by the Ministry of Labor and Immigration10 at the end of 2011 indicate that over 23 000 people have taken part in this program, including direct beneficiaries and their relatives (there are fewer than 10 000 direct beneficiaries). Most of the beneficiaries are from Latin American countries. The majority are from Ecuador, followed by Colombia, Argentina, Peru and Brazil. This program has been managed by State Employment Service—Servicio Público de Empleo Estatal (SEPE)— and the General Directorate for the Integration of Immigrants (Ministry of Labor).

There is also another, much smaller, voluntary return program called "productive return" designed to promote projects in micro-businesses or small family businesses to enterprising people wishing to return to their countries of origin. The requirements these people must meet are similar to those in the other program. However, before returning, they are prepared and trained and various feasibility studies are carried out to guarantee the success of these small businesses in the countries of origin. The number of people taking part in this program is under 200. Beneficiaries are mostly Ecuadorians, Bolivians, Colombians, Senegalese and Peruvians. Ecuadorians and Bolivians account for over 50 percent of the total.

There are also programs financed by various autonomous communities to support returns, as well as occasional assistance from some municipalities that also focus on supporting immigrants wishing to return to their countries of origin. These programs mainly establish occasional financial assistance to pay for the trip, work orientation or financing related travel costs but are fairly limited. These kinds of programs have been implemented by regions with the largest immigrant populations, such as Catalonia and Madrid.

The total number of people taking part in these voluntary return programs between 2008 and the end of 2011 is over 31 000, the majority within the APRE program. However, the numbers within the productive return programs are barely worth mentioning (see table 6). Voluntary returns have not been very high if one considers the severity of the economic crisis. These returns have been more common among immigrants from Latin American countries, especially Ecuadorians, but the programs have had very little impact in the case of Moroccan migrants.

Despite the severity of the economic crisis, in 2008 the government announced its aim of protecting the most vulnerable migrants and preserving their economic and social rights. Protection of resident immigrants became a political priority, given the high level of unemployment among this group, which is much higher than among nationals. In 2011, nearly five million people were unemployed in Spain, equivalent to an unemployment rate of over 21 percent. However, among immigrants the percentage was even higher, over 32.72 percent. The difference between nationals and foreigners has been growing since 2006 and in 2011 was just over 13 percentage points (see table 7). Unemployment not only seriously affects the living conditions of immigrant families, it also can make it very difficult to maintain legal residency, as employment is a requirement for renewing work permits.

The data provided by the Spanish Ministry of Employment and Social Security—Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social (2011)—showed that the number of foreign workers registered as unemployed was greater than 500 000 in 2010 and 2011. In 2011 Moroccans constituted 24 percent of this figure, Ecuadorians nine percent and Colombians 6.5 percent (see table 8). Unfortunately, data broken down by nationals from eu countries are not available disaggregated by nationality, so it is impossible to show unemployment levels among Romanians. Although unemployment affects all nationalities, it is particularly high among Moroccans and Algerians. The number of foreigners receiving unemployment benefits has grown at a significant rate since 2007 and dropped in 2011. In 2010 over 450 000 foreigners were receiving these benefits, 23.06 percent of whom were Moroccans. These graphs demonstrate the need to maintain and promote initiatives designed to ensure the social protection of immigrants residing in Spain.

The reforms in immigration legislation and the approval of the Integration and Citizenship Plan—"Plan estratégico de ciudadanía e integración"—are aimed at maintaining social cohesion. This focus on integration is the result of the maturation of the migration phenomenon in Spain, which shows the consolidation of settlement and the positive results provided by the integration indicators. Current data show that approximately 70 percent of non-EU foreigners have a stable work permit (just over 50 % are permanent). Over the past few years, the number of residence permits granted for family reunification has grown significantly and in the 2010/11 academic year there were over 770 000 foreign students in the Spanish public school system (excluding university). Other significant demographic indicators are that a quarter of all annual births in Spain involve a foreign parent while marriages which include at least one foreigner have tripled over the past decade (Izquierdo, 2011).

Between 2008 and 2011 there have been no significant changes in Spanish integration policy. The modification of the Aliens Law (Gobierno de España, 2011) increased the requirements for family reunification, both for those applying for their families to join them in Spain (who must have a permanent residence permit) and for those wishing to come to Spain to join a family member (who must be over retirement age). However, at the same time, the law extends some rights, such as the guarantee of legal assistance to irregular immigrants, prolongation of the right to education for foreign children ages 16 to 18 years and the extension of the right of family reunification to unmarried couples who are cohabitating.

The new "Plan estratégico de ciudadanía e integración 2011-2014" (Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración, 2011) is a document that seeks to reinforce integration instruments and policies, such as public services and participation, in order to guarantee that all citizens, foreign and national, have equal access to public institutions and resources. The most important objectives of this plan include incorporating new measures to fight discrimination and promote equal opportunities, use integration as a mainstreaming measure in all public policies, improve social cohesion and increase the public participation of migrants in all social spheres and institutions.

The greatest constraint on maintaining an integration policy is budget cuts. In 2005 the government approved the Fund to Support the Acceptance and Integration of Immigrants and Educational Reinforcement—"Fondo de Apoyo a la Acogida e Integración de Inmigrantes y al Refuerzo Educativo"—(Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social, 2005). The goal of this fund was to guarantee that the autonomous communities and local administrations had sufficient funds to cover the educational, health, social and housing costs of immigrants.

These funds were transferred from central administration to autonomous communities, which in turn distributed 40 percent of these resources to local governments with an immigrant population of over five percent registered in their territory. The distribution of resources was determined by the size and composition of the immigrant population. In 2005 120 million euros were distributed from this fund, a quantity that predictably increased over the next few years to approximately 200 million euros per year. The economic crisis virtually halved this fund.

Conclusions

The Spanish migration transition was extremely rapid and intense. Throughout the last decade, the economic boom in Spain, based on the construction and tourism sectors, increased the demand for low-skill workers in occupations that were unappealing to the Spanish population. As a result, these kinds of positions were mostly filled by foreign citizens. During the middle of the past decade, Spain became the main destination country for migrations to the European Union and its foreign population grew to over 12 percent of the total population in just over 20 years. During the 1990s, Spanish immigration policy was at an early stage of experimentation, developing a reactive approach with little state intervention and partial measures in the area of integration. After 2004, however, the policy became proactive through measures that were much more closely tailored to the needs of the labor market and there was an increase in government action regulating the arrival of foreign workers from abroad. The Spanish economic crisis, the most worrisome aspect of which is the massive job loss has had a significant impact on the dynamics of migration flows and immigration policy. Regarding migration flows, first of all, there has been a noticeable slowdown in arrivals and a growing increase in departures among both foreigners and nationals. The economic crisis has not had a significant impact on the policy to control migration flows, except to increase internal control. In the past few years, the fight against irregular immigration, incorporated into Spain's security agenda, has included other objectives such as the fight against organized crime and the protection of women who are the victims of trafficking.

The most significant changes have occurred in the area of flow management. Here there has been a shift from a policy whose principle objective was to recruit workers to meet labor market demands to a policy focusing on improving the "employability" of unemployed resident immigrants, ensuring their social protection and promoting induced returns. Between 2007 and 2011 there have been no major changes in the area of integration, except for greater emphasis on actions in the fight against racism and xenophobia.

However, as a result of the change of government in 2012, the future of this field is unclear. For example, early statements issued by the new administration have suggested reforming the process that allows foreigners to legalize their status through long-term residence in the country, a permanent mechanism that has allowed many immigrants to legalize their situation during the economic crisis. In addition, the structure of the government has been reorganized, once again giving the Ministry of the Interior greater protagonism in this material, over the Ministry of Labor, a good indication that the new government understands migration more in terms of security and internal control than of the needs and dynamics of the labor market. Moreover, in April 2012, the new conservative government passed a new healthcare law reform. The reform included the co-pay system for medicines, several measures to improve efficiency, and elimination of free medical care for irregular immigrants.

References

ARANGO, Joaquín; Eliseo AJA, and Josep OLIVER, 2011, dirs., Inmigración y crisis económica: Impactos actuales y perspectivas de futuro. Anuario de Inmigración en España, edición 2010, Barcelona, CIDOB/Diputació de Barcelona/Fundación Ortega-Marañón/Unicaja/Fundació ACSAR/Centro de Estudios Andaluces. [ Links ]

ARTEAGA, Félix, 2011, "Sobre la estrategia española de seguridad", Notas de actualidad: Q&A del Real Instituto Elcano, Madrid, Real Instituto Elcano. [ Links ]

BANK OF SPAIN, 2012, Statistics Bulletin. Main Economic Indicators, Madrid, Bank of Spain. [ Links ]

CACHÓN, Lorenzo, 2009, La España inmigrante: Marco discriminatorio, mercado de trabajo y políticas de integración, Barcelona, Anthropos. [ Links ]

CEA D'ANCONA, María Ángeles, and Miguel S. VALLES MARTÍNEZ, 2011, Evolución del racismo y la xenofobia en España. Informe 2011, Madrid, Subdirección General de Información Administrativa y Publicaciones-Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración. [ Links ]

CEBOLLA, Héctor; Ruth FERRERO, and Ana LÓPEZ-SALA, 2012, "Case-Study: Spain", Labour Shortages and Migration Policy, Geneva, IOM. [ Links ]

COUNCIL OF EUROPE, 2005, Convention on Action against trafficking in Human Beings, Warsaw, The Secretary General of the Council of Europe. [ Links ]

DE LUCAS, Javier, and Laura DÍAZ, 2006, La integración de los inmigrantes, Madrid, Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. [ Links ]

DE LUCAS, Javier, and Ángeles SOLANES, 2009, La igualdad en los derechos. Clave de la integración, Madrid, Dykinson. [ Links ]

ELIAS, Joan, 2011, "Inmigración y mercado laboral. Antes y después de la recesión", Documentos de Economía "La Caixa", Barcelona, no. 20, March. [ Links ]

EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY STUDIES (EUISS), 2003, Una Europa segura en un mundo mejor, Brussels, European Security Strategy. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ-CORDÓN, Juan Antonio, 2001, "El futuro demográfico y la oferta de trabajo en España", Migraciones, no. 9, pp. 45-68. [ Links ]

FERRERO, Ruth, and Ana LÓPEZ-SALA, 2010, "Spain", in Frank Laczko et al., eds., Migration and the Economic Crisis in the European Union. Implications for Policy, Geneva, IOM/Inde-pendent Network of Labor Migration and Integration Experts. [ Links ]

GOBIERNO DE ESPAÑA, 2009, Real Decreto por el que se modifica el Reglamento de la Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social, aprobado por el Real Decreto 2393/2004, de 30 de diciembre, Madrid, Consejo de Ministros-Presidencia del Gobierno, July 10. [ Links ]

GOBIERNO DE ESPAÑA, 2011, Ley Orgánica 10/2011, de 27 de julio, de modificación de los artículos 31 bis y 59 bis de la Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social, in Boletín Oficial del Estado, no. 180, sec. I, July 28. [ Links ]

GODENAU, Dirk et al., 2012, "Labour Market Integration and Public Perceptions of Immigrants: A Comparison between Germany and Spain during the Economic Crisis", Comparative Population Studies, vol. 37, no. 1-2. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA (INE), 2012a, "Municipal Register", Madrid, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA, 2012b, "The Residential Variation Statistics (RVS)", Madrid, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA, 2012c, "Encuesta de población activa (EPA)", Madrid, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. [ Links ]

IZQUIERDO, Antonio, 2008, "El modelo de inmigración y los riesgos de exclusión", Informe Foessa 2008, Madrid, Cáritas. [ Links ]

IZQUIERDO, Antonio, 2011, "Panorámica de la inmigración en España", in Seminario España-Canadá: "Estado de la cuestión sobre el estatuto de los inmigrantes", Madrid, Secretaría de Estado de Inmigración/Fundación Canadá, October, 27-28. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ-SALA, Ana, 2007, "El gobierno de la inmigración en España: Entre el criterio de eficacia y el de legitimidad política", Spagna Contemporanea, Turin, Italy, Instituto di Studi Storicie Gaetano Salvemini, no. 31, pp. 77-92. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ-SALA, Ana, 2012, "The Political Design of Migration Control in Southern Europe", in Cristina Gortázar et al., eds., European Migration and Asylum Policies: Coherence or Contradiction, Brussels, Bruylant. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ-SALA, Ana, and Ruth FERRERO [paper], 2009, "Economic Crisis and Migration Policies in Spain. The Big Dilemma", in "Annual Conference 2009. New Times? Economic Crisis, Geo-Political Transformation and the Emergent Migration Order", Oxford, Centre on Migration, Policy and Society-University of Oxford. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ-SALA, Ana, and Valeriano ESTEBAN, 2010, "La nueva arquitectura política del control migratorio en la frontera marítima del suroeste de Europa: Los casos de España y Malta", in Ana López-Sala, and María Eugenia Anguiano, eds., Migraciones y fronteras. Nuevos contornos para la movilidad internacional, Barcelona, Icaria/CIDOB. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DEL INTERIOR [digital publication], 2012, "Balance 2011. Lucha contra la inmigración ilegal", Madrid, Ministerio del Interior-Gobierno de España, February. Available at <http://www.interior.gob.es/file/54/54239/54239.pdf> (last accessed on February 2, 2012). [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE EMPLEO Y SEGURIDAD SOCIAL, 2005, "Fondo de Apoyo a la Acogida e Integración de Inmigrantes y al Refuerzo Educativo", Madrid, Secretaría de Estado de Inmigración y Emigración-Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE EMPLEO Y SEGURIDAD SOCIAL, 2008, "Programa de Ayudas Complementarias de Abono Acumulado y Anticipado de la Prestación Contributiva por Desempleo a Trabajadores Extranjeros Extracomunitarios que Retornen Voluntariamente a sus Países de Procedencia (APRE)", Madrid, Secretaría General de Inmigración y Emigración-Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE EMPLEO Y SEGURIDAD SOCIAL, 2011, Anuario de estadísticas del Ministerio de trabajo e Inmigración 2010, Madrid, Subdirección General de Estadística-Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE TRABAJO Y ASUNTOS SOCIALES, 2007, "Plan estratégico de ciudadanía e integración social 20072010. Resumen ejecutivo", Madrid, Subdirección General de Información Administrativa y Publicaciones-Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE TRABAJO E INMIGRACIÓN, 2011, "Plan estratégico de ciudadanía e integración 2011-2014. Resumen ejecutivo", Madrid, Dirección General de Integración de los Inmigrantes-Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

ORGANIZACIÓN INTERNACIONAL PARA LAS MIGRACIONES (OIM), 2003, "Programa de Retorno Voluntario de Inmigrantes desde España (Previe)", Madrid, Delegación del Gobierno para la Extranjería y la Inmigración-Ministerio del Interior. [ Links ]

ROJO, Eduardo, and Ferrán CAMAS, 2010, "Las reformas en materia de extranjería en el ámbito laboral", Revista Andaluza de trabajo y Seguridad Social, Consejo Andaluz de Relaciones Laborales, no. 104. [ Links ]

SINDICATO UNIFICADO DE POLICÍA (SUP), 2009, "Press Released Archives", Madrid, Sindicato Unificado de Policía, no. 9, February. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS (UN), 2011, "Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination", New York, United Nations General Assembly [Official Records. Sixty-sixth session. Supplement no. 18 (A/66/18)] [ Links ].

1 The short-term population projection for Spain compiled by the INE constitutes a statistical simulation of the demographic size and structure of the population residing in Spain, its autonomous communities and provinces during the forthcoming 10 years. This statistical operation is carried out annually.

2 This article only considers changes in migration policy between 2008 and 2011. With the change of government in 2012 the future of the integration and recognition of rights for immigrants in Spain remains unclear. One of the key factors of immigrant's integration was dismantled by the new government in April, 2012: the universal access to the healthcare system.

3 The registries only reflect the fact that an individual is no longer registered (presumably because of leaving the country), but do not provide information on whether they returned to their country of origin or went to a third country.

4 The "Economically Active Population Survey" (EAPS) is a continuous quarterly survey targeting households designed to obtain data on the labor force (sub-categorized by employed and unemployed), and people outside the labor market.

5 This refers to expulsions of foreign offenders with extensive criminal records who could be considered threats to public safety. In 2009, the Spanish Ministerio del Interior (Ministry of the Interior) created the Brigada de Expulsión de Delincuentes Extranjeros (Expulsion of Foreign Offenders Brigade or Bedex), within the national police.

6 Strait of Gibraltar and Canary Islands.

7 Organic Law on Rights and Freedoms of Aliens in Spain and their Social Integration (Aliens Law) (Gobierno de España, 2011) establishes four categories of repatriation: refusal of entry refers to people rejected at authorized border posts, usually ports and airports; readmission refers to expulsions performed according to readmission agreements with third countries; returns refer to people apprehended trying to enter Spain through unauthorized parts of the border; and expulsions are repatriations for reasons specified in the Aliens Law and carried out through administrative proceedings.

8 The Special Catalog of Vacant Jobs that constitutes a list of professions for which the labor market experiences shortages of workers. The list, created by the public employment services, is approved and renewed every quarter.

9 Agreements are in place with Morocco, Ecuador, Peru, Argentina, Ukraine, Colombia, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Andorra, the United States, Canada, Australia, Philippines, Dominican Republic, Tunis, Russia and Paraguay.

10 These data on the two voluntary return programs in the complete series until 2010 were requested through an official letter from Spanish National Research Council—Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC)—and provided by officials from the Ministry of Labor and Immigration.

INFORMACIÓN SOBRE LA AUTORA

ANA MARÍA LÓPEZ-SALA: Es doctora en sociología por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, y en paz y seguridad internacional por el Instituto Universitario General Gutiérrez Mellado de la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED, España). Investigadora en el Instituto de Economía, Geografía y Demografía del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC, España). Su investigación se centra en el análisis comparado de políticas migratorias, en especial en el control de flujos, las políticas de admisión, la trata de personas y los vínculos entre seguridad y derechos humanos. Es miembro de los equipos de investigación del Transnational Immigrant Organizations and Development Project (Princeton University) y The Fight Against Trafficking in Human Beings in Europe (Comisión Europea) e investigadora principal de Circular Project (Temporary Immigration Programs and Circular Migration in Spain, 2000-2010). Ha realizado estancias de investigación en universidades de Estocolmo, Utrecht, York (Canadá), en el University College London, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, la McGill University y el Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique de la Université du Québec à Montréal. En 2009 se desempeñó como Rockefeller Research Fellow en Bellagio (Italia). Entre sus publicaciones destacan: Inmigrantes y Estados: La respuesta política ante la cuestión migratoria (Anthropos, 2005) y Migraciones y fronteras: Nuevos contornos para la movilidad internacional (CIDOB-Icaria, 2010). Dirección electrónica: ana.lsala@cchs.csic.es.