Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Migraciones internacionales

On-line version ISSN 2594-0279Print version ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.5 n.4 Tijuana Jul./Dec. 2010

Artículos

Emigration Policy and State Governments in Mexico

Política de emigración y gobiernos estatales en México

Guillermo Yrizar Barbosa y Rafael Alarcón

El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Dirección electrónica: gyrizar@colef.mx ; ralarcon@colef.mx

Date of receipt: September 14, 2009.

Date of acceptance: November 4, 2009.

Abstract

Several Mexican state governments have created institutions and developed public policies to benefit their emigrants abroad following the federal government's lead. The main objective of this article is two–fold: first, to analyze the three sociopolitical factors that influenced the emergence of emigration policy at the state level, and second, to examine two strategic activities undertaken by state governments in the Central Western region. Public agencies for international migrants carry out various actions such as administering federal government programs, preserving regional identities, promoting human and civil rights for migrants, locating missing persons, and processing official documents. Many of these activities are complementary to those undertaken by federal government. However, some of these agencies play a strategic role in the repatriation of the bodies of Mexican migrants that die in the United States and the management of temporary employment abroad for their citizens.

Keywords: international migration, emigration policy, state governments, Mexico, United States.

Resumen

Varios gobiernos estatales en México han creado instituciones y desarrollado políticas públicas para beneficiar a sus emigrantes en el extranjero, siguiendo el ejemplo del gobierno federal. El objetivo principal de este artículo tiene dos vertientes: primero, analizar los tres factores sociopolíticos que influyeron en el surgimiento de la política de emigración a nivel estatal y, en segundo lugar, examinar dos actividades estratégicas llevadas a cabo por gobiernos estatales en la región centro–occidente. Las agencias públicas para migrantes internacionales llevan a cabo diversas acciones tales como la administración de programas federales, la preservación de las identidades regionales, la promoción de los derechos humanos y civiles de los migrantes, la localización de personas perdidas y el trámite de documentos oficiales. Muchas de estas actividades son complementarias a las que realiza el gobierno federal; sin embargo, algunas de estas agencias tienen un papel estratégico en la repatriación de los restos de los migrantes mexicanos que mueren en Estados Unidos y en la gestión del empleo temporal para sus ciudadanos en el exterior.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, política de emigración, gobiernos estatales, México, Estados Unidos.

Introduction1

Overcoming a past of indifference and negligence, since the early 1990s, the Mexican State has implemented an active approach towards Mexicans abroad. This radical change has materialized in two major constitutional reforms: the passage of the Ley de nacionalidad in 1997, allowing those that decided to adopt another nationality to preserve their Mexican nationality, and the passage of reforms to the Código federal de instituciones y procedimientos electorales (Federal Code of Institutions and Electoral Procedures) in 2005, enabling Mexicans to vote from abroad, which occurred for the first time in the 2006 presidential election. Nationwide, the federal government created the Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (Institute for Mexicans Abroad) in 2003, as a decentralized body of the Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (Foreign Affairs Ministry), "to promote strategies, incorporate programs, and obtain recommendations to improve the living standards of Mexican communities abroad."2 Thus, Mexico with an enormous diaspora concentrated virtually entirely in the United States, joined countries such as the Philippines and Morocco which, with different forms of government, implemented a national emigration policy (Asis, 2006; Brand, 2006; Durand, 2004; García y Griego, 2006; Alanís, 2006; González, 2006; Imaz, 2006; Alarcón, 2006; Yrizar, 2008, 2009; Fitzgerald, 2009).

Like federal government, several Mexican state governments and certain municipalities have created institutions and developed public policies for their emigrants in the United States. The governments of Michoacán and Zacatecas are pioneers in some of these initiatives. On the one hand, Michoacán is the only state to have granted the right to vote for its governor from abroad and the only one to have a Secretaría del Migrante in operation since 2008. The state of Zacatecas initiated the internationally known 3x1 Program (García Zamora, 2006:158), that has become a federal government program and has come to be regarded as the "first transnational policy in Mexico" (Fernández, García Zamora and Vila, 2006). Zacatecas was also the first state to carry out a constitutional reform of migrants' civil rights, called Ley migrante, which allows absent citizens to run for public office in their state (Moctezuma, 2003). State governments have not only implemented federal initiatives, but have also been concerned with "governing migration" (Irazuzta and Yrizar, 2006).

The main objective of this article is two–fold: first, to analyze the three sociopolitical factors that have influenced the emergence of emigration policy at the state level in Mexico, and second, to examine two strategic activities undertaken by two states regarding international migrants: the repatriation of the bodies of Mexican migrants who die in the United States and the management of temporary employment in the United States and Canada.

This study focuses on states in Central Western Mexico, the traditional region of migration to the United States (Massey et al., 1987), and seeks to contribute to the incipient academic research on state governments' actions regarding international migration to the United States, as Goldring (2002), Michael Smith (2003), Escala (2005), Valenzuela (2006), Vila (2007), and Fernández et al. (2007) have already shown, among others.

It is necessary to analyze emigration policy at the state level in Mexico because in the United States and other parts of the world, sub–national governments often implement their own immigration policy even though this is a function of the central or federal government. In recent years, sub–national governments in the United States have implemented an increasing number of actions affecting immigrants, such as the decision by states, counties and cities to enter into agreements under the 287(g) program with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to enable state and local law enforcement agencies to enforce immigration law. Conversely, other cities have become sanctuaries in order to prevent access by ICE.

Likewise, certain state and local governments place restrictions on access to public services, renting homes or obtaining driver lICEnses for undocumented migrants. This issue has sparked a debate on the competence and cooperation that should exist between government levels regarding the different effects of immigration, as Antonio Izquierdo and Sandra León (2008) pointed out regarding the model of autonomous communities in Spain.

This study is divided into four sections: the first contains a theoretical discussion to validate the concept of emigration policy. The second analyzes the sociopolitical factors that led to the emergence of this policy at the state level in Mexico. The third describes the public agencies for international migrants at the state level in Mexico's Central Western region while the fourth examines two strategic activities undertaken by certain Mexican state governments to benefit their migrants. The final section discusses the main findings and conclusions of the study.

Theoretical Approaches to the Concept of Emigration Policy

The concept of emigration policy has only recently been analyzed. It began to be accepted in the literature on migration studies as a result of Barbara Schmitter Heisler's (1985) seminal study. National emigration policy is defined as the set of decisions and public actions that states' central governments establish to manage the departure to other countries and the return of their citizens (by land, sea or air) as well as the design of public policies through institutions and programs to establish linkages with emigrants residing permanently or temporarily abroad.

In this respect, David Fitzgerald (2009:33) distinguishes between emigration policies, designed to control citizens' departure and return, and emigrant policies to strengthen ties with citizens who are already abroad. For his part, Alan Ganlen (2008:842) uses the concept of diaspora engagement policies to describe how states of origin appropriate emigrants by treating them as members of the society of origin with the rights and obligations of associated members.

But it was James Hollifield (2004) who opened up a very promising avenue for understanding how national states design emigration policies. Based on the analysis of immigration policy in Europe and the United States, the author considers that states' functions have evolved over time. They are initially defined by their military and security functions for protecting the territory and the population. Subsequently, and at least since the start of the Industrial Revolution, the Trading State has emerged which, in addition to its security functions, assumes an economic function to construct favorable regimes for trade and investment.

The second half of the 20th century has seen the emergence of the Migration State, the main purpose of which is to regulate international migration. James Hollifield (2004:903) argues that the emergence of the Trading State necessarily involves the emergence of the Migration State, since the wealth, power and stability of the state is increasingly dependent on its willingness to accept trade and migration, especially in contexts of regional economic integration (Hollifield, 2004:901).

On the basis of James Hollifield's (2004) concept of the Migration State, one can hypothesize the parallel emergence of the Emigration State in countries where a high proportion of citizens are emigrants residing abroad. This might be the case of the Philippines, Morocco and Mexico, whose states, in addition to evolving on their security functions and those required for guaranteeing trade and international investment, have regulated the departure and return of their emigrants, who constitute a significant portion of the population and contribute to national economies by sending monetary remittances. These states have also striven to reach out to their diasporas by offering them various types of membership.

The Philippines is one of the most emblematic cases of institutional support for international emigrants since the central government created the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA). In 2005, this agency directly administered the departure and rehiring of nearly a million Filipinos as temporary workers abroad, reinforcing the policy of labor exportations initiated in the mid–1970s (POEA, 2005).

Alan Ganlen (2008:851) argues that although all countries have emigrants, and many devote part of their state apparatus to them, this issue has been ignored. Following James Hollifield (2004), he calls this portion of the states dedicated to emigrants the Emigration State, which is considered abnormal, since the modern geopolitical imagination regards the nation–state territorial unit as the ideal model of political organization.

Barbara Schmitter Heisler (1985) documented the emergence of emigration policies by migrant sending countries such as Algeria, Spain, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Turkey and Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s. These countries created government institutions dedicated to emigrants and tried to promote long–term temporary migration for their citizens. The author notes that states with a long history of emigration such as Italy and Spain tended to have more developed, coordinated emigration policies.

Various Italian governments developed a network of organizations, institutions and agencies that were directly or indirectly linked to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Consulates located in countries with large contingents of Italian emigrants dealt with their family, employment and social security problems and reported directly to the Direzione dell'Emigrazione at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Spain, with its long history of emigration to its former colonies and European countries from the mid–1960s onwards, set up the Instituto Español de la Emigración as part of the Secretary of Labor, which operated through the consulates. A 1971 law was designed to encourage the creation of associations to reinforce Spanish identity and enable emigrants to maintain close links with Spain.

In the case of Mexico, Jorge Durand (2004) considers that there have been five phases during the hundred years of development of an emigration policy. In the early 20th century, this policy was designed to dissuade Mexicans from migrating to the United States. During and after the Second World War, a negotiation policy was implemented through the Bracero Program. Subsequently, Jorge Durand used the phrase "laissez–faire policy" to describe the Mexican government position between the 1970s and 1980s. Manuel García y Griego (1988) had previously identified this period as "a policy of no policy".

The 1990s saw a damage control policy that was linked to the Mexican diaspora's opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement. During the last stage, at the beginning of President VICEnte Fox's administration, Jorge Durand (2004) erroneously perceived the development of proposals that pointed towards a policy of "shared responsibility" with the U.S. government. As eventually proved, there was never any attempt at joint responsibility by the U.S. Congress, which implemented a national security policy regarding immigration in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks.

David Fitzgerald (2009:155) argues that the Mexican government attempted to control the volume, length of trips, skills and geographical origin of emigrants to the United States between 1900 and the early 1970s. Since the late 1980s, it has changed its policy towards the management of emigration.

Rafael Alarcón (2006) considers that the acceptance of Mexico as a country of emigrants and therefore the start of a clear emigration policy began in the early 1990s due to a combination of various processes. In addition to the crisis caused by the electoral fraud in the 1988 presidential elections and the Mexican government's attempts to secure passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement, three other factors explain the emergence of Mexico's emigration policy: 1) the rapid growth of the Mexican population in the United States in the 1990s; 2) the favorable public perception of migrants in Mexico due to the large family and collective remittances they sent from the United States; and 3) the triumph of Proposition 187 in California in 1994 that was supported by 59 per cent of the electorate that sought to prohibit the provision of social services through public funds for undocumented persons living in that state.

The countries and sub–national units that implement public policies for emigrants through government institutions and programs are usually those that experience high emigration rates and reception of remittances. That is why the Mexican case is not unique worldwide.

A little–known case at the sub–national level is that of Kerala, a state in South Western India with a Department for Non–Resident Keralites' Affairs. Kerala, with a similar population to California (over 30 million) in a territory the size of The Netherlands, has an agency that overtly promotes emigration and the attraction of remittances.3

Lastly, the concept of "federative diplomacy," also known as "para–diplomacy" (Schiavon, 2004; Velázquez Flores, 2006) is valuable to substantiate the concept of emigration policy at the state level in Mexico. Federative diplomacy holds that Mexican states implement a foreign policy of their own as a result of decentralization, democratization and the emergence of regions in response to globalization that has created an incentive for states to seek greater participation within the international arena in order to support their exports and portray themselves as ideal places for receiving direct foreign investment (Schiavon, 2004).

The Emergence of Emigration Policy at the State Level in Mexico

Guillermo Yrizar Barbosa (2008) argues that there are at least three sociopolitical factors that explain the emergence of a state–level emigration policy in Mexico. The first is the recommendation by the Foreign Affairs Ministry, in 1990, to create state authorities for dealing with migrants abroad, following the model of the Programa para las Comunidades Mexicanas en el Exterior (PCME) (Program for Mexican Communities Abroad) (Figueroa–Aramoni, 1999; Robert Smith, 2003:310; Vila Freyer, 2007).

The second factor is the increasing migrants' demands for public attention to state offices in Mexico, particularly from braceros. However, those that most demanded consideration were organized migrants from hometown associations (HTA) and federations of Mexicans abroad, partly thanks to their presence in public opinion as a result of the visibility they have acquired as senders of monetary remittances. There was also an increase in citizens' demands that state governments ensure the repatriation of the deceased and the location of migrants that had gone missing during their undocumented border crossing or within the United States.

A third factor is the political and electoral interest that governors, local congresses, political parties and other social actors at the state level have shown in international migration. This includes what has been called the "cascade effect", which consists of imitating the activities certain states are undertaking in relation to the migration issue. The exchange of experiences among states helped governments and their agencies to achieve better practices in their actions towards migrants and their families.

As for the origin of public agencies for international migrants in Mexican states, the PCME was undoubtedly a key element, since it was a government strategy that required the participation of state administrations in reaching out to their diasporas. This has been pointed out by Goldring (2002:67) who holds that in view of the erosion of the Programa de Solidaridad Internacional during President Carlos Salinas de Gortari's administration, the PCME attempted to encourage governors of sending states who had not reached out to their migrants to do so. As Michael Peter Smith (2003) has noted ensuring the success of the PCME, required states' participation in approaching the regional diasporas, which meant that each state acted differently.

Zacatecas was the pioneering state in cooperating with migrants through the 1 x1 Program implemented in the late 1980s, when the migrants and the state government contributed with one dollar each to finance public infrastructure (García Zamora, 2006).4 However, during this period there was no public agency for international emigrants because the state government was only interested in managing the investment of collective remittances. In this respect, the first public agency for international migrants, devoted exclusively to residents in the United States and their relatives in Mexico, was not created in Zacatecas but rather in Michoacán in 1992.

The Dirección de Servicios de Apoyo Legal y Administrativo a Trabajadores Emigrantes (DSALATE) (Office of Legal and Administrative Support Services for Emigrant Workers), was created on June 22, 1992, within the Subsecretaría de Gobernación del Estado, through an administrative agreement published in the official state journal during the administration of the interim governor of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) (Institutional Revolutionary Party), Genovevo Figueroa Zamudio (1988–1992).

DSALATE began its activities with very few resources and personnel due to the fact that its main task was to provide support for the repatriation of the deceased. Claudio Méndez, former director of the Coordinación General para la Atención al Migrante Michoacano, declared that the institution that existed in 1992 was virtually and exclusively devoted to repatriating the bodies of Michoacanos who had died in their attempt to cross the Mexican Northern border or in the United States.5

An important factor that explains the appearance of public agencies for international migrants in Michoacán is the movement of former braceros that emerged in the municipality of Puruándiro. According to Jesús Martínez Saldaña, the last director of the Instituto Michoacano de los Migrantes en el Extranjero (IMME), this initiative was put forward by Ventura Gutiérrez Méndez, leader of the "Braceroproa" group, and a native of this municipality, which has a long tradition of migration to the United States.6 According to Ventura Gutiérrez, on July 1, 1996, the Casa del Trabajador was set up to deal with the problems of migrants and their families in his hometown. Two years later, it spawned the movement of former braceros.7

Nearly sixteen years after the first public agency for emigrants was created in Michoacán, the Secretaría del Migrante came into being in 2008. This institution was created thanks to the modifications to the Ley orgánica de la administración pública del estado of January 3, 2008 (H. Congreso del Estado de Michoacán de Ocampo, 2008). Article 27 of this law describes the 19 functions of this secretaría, the first of which provides a general ideal of the aim of this new public agency: "formulate, promote, instrument and evaluate public policies for Michoacán migrants in order to promote their integral economic, social, cultural and political development."

In the case of Zacatecas, the PRI's defeat in the gubernatorial elections in the late 1990s and the victory of the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) (Democratic Revolution Party) led to the institutionalization of a new organization for migrants in the government structure. The successful candidate, Ricardo Monreal (1998–2004), acknowledged the support of the Zacatecanos in the United States by creating the Dirección de Atención a Comunidades Zacatecanas en el Extranjero at the start of his term.

A similar political situation accompanied the formation of public agencies for migrants in other states. The arrival of the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) (National Action Party) and the departure of the PRI from the governorships of Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Jalisco, San Luis Potosí and Nayarit led to an increase in government activity towards emigrants and their families. It should be noted, however, that the PRI administrations prior to the party transitions in Zacatecas, Michoacán and San Luis Potosí already had blueprints for the creation of migrants' agencies that were adopted by the incoming administrations. In this respect, the participation of state government representatives in the Coordinación Nacional de Oficinas de Atención a Migrantes (Conofam) (National Coordination of Migrant Service Offices) proved crucial in ensuring that the states learned and exchanged "best practICEs" in terms of structure, services and actions that would enable them to work and improve relations with emigrant communities.

The participation of organized migrants in elections at the state level has been crucial in demanding the creation of agencies for international migrants. In Michoacán and Zacatecas migrants have become truly transnational political actors who have sought to consolidate their presence in public opinion.

Public Agencies for International Migrants in Central Western Mexico

Since the mid–1990s, state governments in the Central Western region of Mexico have negotiated and cooperated with migrants' organizations (i.e. HTAs) in the United States in promoting community development through investment in public infrastructure and social projects. Some of the best–known cases include Zacatecas, Jalisco, Michoacán and Guanajuato. However, other states in the same region have also begun to develop public policies for their residents abroad, such as Aguascalientes, Colima, Durango and San Luis Potosí.

Central Western Mexico is known as the traditional region of emigration to the United States thanks to its history and high emigration rates (Massey et al., 1987; Durand and Massey, 2003; Conapo, 2006). Between 1925 and 2000, over 50 per cent of Mexican international migrants were born in this region, mainly in the states of Zacatecas, Michoacán, Jalisco and Guanajuato (Durand and Massey, 2003). These four comprise the group of states of most interest, since they lead the sociodemographic and economic indicators linked to international migration. This situation has justified the broad and varied academic research conducted on these states since the pioneering work of Paul S. Taylor (1933) in Arandas, Jalisco.

Table 1 shows the importance of the relationship between the states of Central Western Mexico and the United States in which Zacatecas, Jalisco, Michoacán and Guanajuato reveal their preeminence. The population of these four states accounted for 16 per cent of the total population in Mexico (over 17 million persons) in 2006. It is remarkable that in 2005, 36 per cent of Zacatecanos lived in the United States. Michoacán is in second place with 25 per cent of its citizens residing in the United States. In 2006, this state received nearly 2.5 billion dollars in remittances, the largest amount nationwide, accounting for 13.2 per cent of the state GDP. Zacatecas, Michoacán and Durango, in that order, had the largest proportion of households that received remittances. Finally, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán and Zacatecas account for just over a third of the total number of Mexicans living in the United States.

The degrees of migratory intensity and marginalization estimated by the Consejo Nacional de Población (Conapo) (National Council of Population) in 2000 are significant for the region as a whole. Zacatecas, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Durango and Nayarit have a very high degree of migratory intensity, whereas Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Colima and San Luis Potosí have a high degree. Interestingly, none of the states in the traditional region has a very high degree of marginalization. While Jalisco, Aguascalientes and Colima have a low degree of marginalization, Durango has a medium degree, and the remaining states have a high degree of marginalization. San Luis Potosí stands out has having the sixth highest degree of marginalization nationwide, just below the five most marginalized states in Mexico.8

Over the past ten years, the number of public agencies for migrants has grown, particularly in central–western Mexico. In 1997, Luin Goldring (2002:73) identified nine "state offices for international migrants" in Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas. If Colima, Aguascalientes and Nayarit had had a public organization for migrants during this period, the traditional migration region to the United States would have been the only one in which all the states would have a public agency for international migrants in the late 20th century. In 2003, Michael Peter Smith (2003:473) identified twenty–three states with this kind of organization.

A public agency for international emigrants is a specialized organization, at any level of government, designed to implement policies and operate programs for international migrants, their families and communities of origin in order to address their problems, demands and needs. We have decided to call them agencies rather than offices since each government has a different name for them: secretariats, institutes, offices, centers, direcciones, coordinaciones, departments or units. In Mexico, these organizations are known as Oficinas de Atención a Migrantes (Ofam).

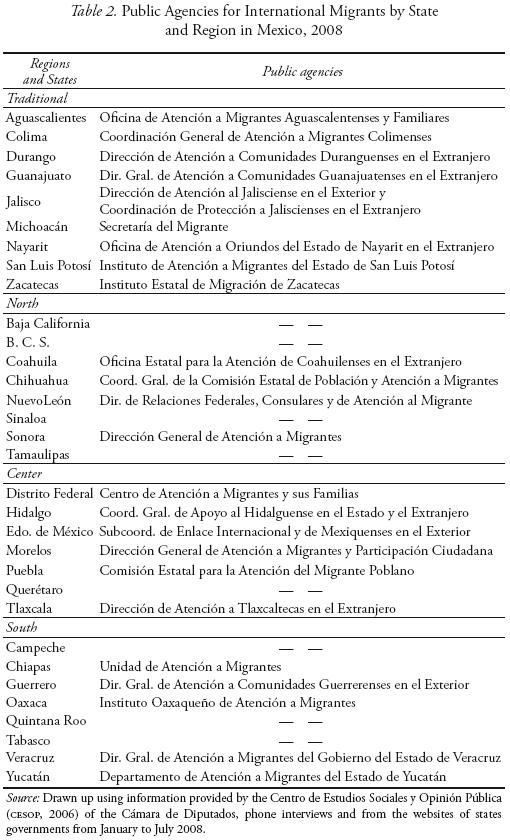

As table 2 shows, in 2008 the central–western region of Mexico is the only one in which all states have a public agency for international migrants. In the case of Jalisco, there are two offices responsible for dealing with the Jaliscienses abroad, although both are located in the Dirección de Asuntos Internacionales. Table 2 also shows that only eight states in Mexico (Baja California, Baja California Sur, Sinaloa, Querétaro, Tamaulipas, Campeche, Quintana Roo and Tabasco) do not have an administrative organization whose name explicitly refers to their migrants or residents abroad. Thus, 24 public agencies for international migrants have been identified at the intermediate government level in Mexico, including the Distrito Federal.

These organizations appear under various names throughout Mexico, which usually contain the name of their target population: migrants. Virtually all the agencies have a welfare–based approach, under the categories of "service, support and protection" with the exception of the Secretaría del Migrante in Michoacán, the Instituto Estatal de Migración de Zacatecas and the Subcoordinación de Enlace Internacional y de Mexiquenses en el Exterior, although in this last state, since it is a coordination office, the role or hierarchy of the agency is lower in comparison with the other two in terms of budget, personnel and programs.

Not all of the state public agencies for migrants have the budget, organization, or the legal instruments to effectively make a difference in reaching out to migrants or meeting their demands. Michoacán stands out because it is a secretaría, giving it the highest hierarchy in government structure in comparison with the other states. As a result, it has a higher operating budget and a larger number of staff than other states.

The most notable presence of state agencies for migrants in Mexican public opinion occurred when nearly a dozen state representatives decided to group together around the migration issue just before the change of political party in the Mexican Presidency in 2000. The Declaratoria de Puebla, the founding document of the Coordinación Nacional de Oficinas de Atención a Migrantes (Conofam) (National Coordination of Migrant Service Offices), was signed by the representatives of 11 states on March 8, 2000.9

The signatory representatives of the Declaratoria de Puebla were drawn from the governments of Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, Michoacán, Zacatecas, Puebla, Oaxaca, Sonora, Jalisco, Querétaro, Morelos and Guerrero. Ana Vila Freyer (2007:79), based on information from the first national coordinator, Mario Riestra from the state of Puebla, declared that Conofam was constituted on the initiative of the first eight states mentioned above.

The two states that had an agency for migrants in 1997 and did not sign the Conofam document were Guanajuato and Durango. Of the eleven representatives that signed the declaration, three came from states not governed by the PRI: Querétaro and Jalisco had PAN executives while Zacatecas was governed by the PRD.10

In the Declaratoria de Puebla, representatives of the signatory governments defined migration as a problem and an opportunity. They also admitted that the attitudes of government, media and organizations of Mexicans abroad towards migrants were sometimes paternalistic but also cooperative.11 It is striking that the founding declaration of Conofam included the states' position on temporary employment abroad. The ninth consideration advocated to "promote binational programs of temporary workers and agricultural day workers between Mexico and the United States to enable many Mexicans to work in a documented manner with access to social security programs in the U.S." It is not surprising that a few years later, Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí should have been the pioneering states in the promotion and supervision of temporary work visas, mediating between legal representatives of U.S. firm, contractors and Mexican workers wishing to secure employment in el Norte.

Two Strategic Activities: Repatriation of the Deceased and Management of Temporary Employment Abroad

Mexican state governments undertake various activities for their emigrants in the United States. The first and one of the most important is the management of federal government programs related to international migration, such as the Programa Paisano, the 3x1 Program, and the Programa Vete Sano–Regresa Sano (Leave Healthy–Come Back Healthy Program). A second activity to which state governments assign a significant part of their budget is the preservation of regional identities among communities of Mexicans living in the United States though the organization of fairs, concerts, bailes, and festivals. The third activity, which is less frequent among agencies but has been identified as an area of opportunity, is the promotion of human and civil rights for migrants, such as voting from abroad. Likewise, state agencies collaborate in the location of missing persons, especially during undocumented border crossing, and in processing official or identity documents such as birth and marriage certificates.

All these activities are part of the emigration policy that public agencies for international migrants from central–western Mexico have carried out since the 1990s. In some cases, these activities are complementary to those implemented by the federal government, however, some state governments play a strategic role in the repatriation of the deceased and in the management of temporary employment abroad for their citizens.

Repatriation of the Deceased

A very sensitive activity among the migrant population in which state governments have specialized with the support of the Mexican consular network, municipal governments and HTAs, is the repatriation of the bodies of Mexican citizens who die in their attempt to cross the border clandestinely or for other reasons in the United States. Between 2000 and 2005, the number of deceased Mexicans repatriated, managed by public agencies for international migrants, significantly increased. According to Fraçoise Lestage (2008:210), the transportation of the remains of Mexican migrants, especially of those from Oaxaca and Michoacán, has increased since 2000. In Oaxaca an 80 per cent increase was detected during the period from 2003 to 2005, rising from 187 in 2003 to 341 in 2005. In Michoacán, the number of repatriations rose from 258 in 2003 to 542 in 2005. Lestage (2008:211) asserts that the number of Mexicans who died in the United States and were repatriated, rose from 3 429 in 2003 to 5 176 in 2005.

According to information from the Instituto de Atención a Migrantes del Estado de San Luis Potosí (Inames), the number of Potosinos who have died on U.S. soil or in their attempt to cross the border and were transported back to their native land has also steadily grown. The period from September 2003 to December 2004 saw 19 repatriations, a figure that nearly doubled in 2005 to 40. In 2007, the total number of repatriations of deceased migrants from San Luis Potosí was 118.

Information from the Instituto Michoacano de los Migrantes en el Extranjero (IMME) and the Inames reveals the migrants' localities of origin, as well as the place where they died in the United States. In the case of the IMME in Michoacán, the total number of repatriations was 294 in 2007; 61 of whom were from the Morelia–center region, 41 from the Meseta Purépecha and the same number from the eastern region. The lowest number of repatriations, six, was recorded in the southern region of Coahuayana followed by the Bajío Zamorano region with seven. In 2005, the Inames in San Luis Potosí followed up 40 repatriations: 18 were from the central zone, where the state capital is located; nine were from the zona media; seven from the Huasteca Potosina and six from the Altiplano Potosino.

In both states, it is interesting to note that traditional migration regions, such as the Bajío Zamorano and the Altiplano Potosino, have very low numbers of registered repatriations, despite having large numbers of migrants in the U.S., as well as a very long history of international migration. This suggests that social integration plays a key role in the decision of migrant families to bury or cremate the bodies of their members in the U.S. rather than transporting them back to Mexico.

In regards to the places where migrants die, the comparison of repatriation records shows the presence of state diasporas in traditional and new destinations. Of the 294 cases attended by the IMME, 131 were recorded in California, 18 in Texas, 16 in Illinois, 16 in North Carolina, 14 in Arizona and lastly 11 each in Florida and Georgia. In the case of San Luis Potosí, of the 40 cases registered by Inames, 13 occurred in Texas, seven in Florida and three in Georgia.

The death of migrants during the undocumented crossing of the U.S.–Mexico border requires special attention. In a recent report, Maria Jimenez (2009) denounced the humanitarian crisis on this border due to the death of over 5 000 persons since 1994. In March 2008, the Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l'Homme (2008) declared that 4 000 persons died between 1993 and 2005 trying to cross the border between Mexico and the United States, "a figure that involves 15 times more deaths in just over a decade than the Berlin wall during its 28 years of existence." As recent studies have shown, it is increasingly dangerous and expensive to cross the border for undocumented persons (Cornelius and Lewis, 2007; Sisco and Hicken, 2009; Fuentes and García, 2009). Unfortunately, given this situation, the public agencies for international migrants must continue with their repatriation programs in order to serve the families of those who perish trying to cross a deadly border.

Management of Temporary Employment Abroad12

The management of temporary employment abroad is another key activity carried out by some state public agencies for international migrants. At least since 2001, the agencies of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Colima and Michoacán, have facilitated the hiring of temporary workers in U.S. and Canadian firms (see Yrizar, 2008).

In 2001, abc correspondent Deborah Amos documented the process whereby legal representatives of U.S. companies and workers from San Luis Potosí met at government offices to select personnel to occupy unskilled positions using H–2 temporary visas (Ruiz Saldierna, 2008:207–209). This report was produced before September 11, 2001, in the context of the migration agreement (acuerdo migratorio) that was negotiated between presidents VICEnte Fox and George W. Bush. This report was broadcast on the Nightline tv program on September 5, 2001 and informed that of 13 000 applicants only 40 were hired to work in a meat packing plant in Texas.

The Dirección General de Enlace Internacional (DGEI) of San Luis Potosí was in charge of organizing meetings between potential candidates and employers. This agency supported U.S. employers by providing health screening and background checks of the candidates. In an interview with Deborah Amos, one of the recruiters stated: "I want somebody who is at least 25, I want somebody who is married, I want someone who has children. He will probably come back to Mexico, I say 99 per cent chance of that, when his visa is up".

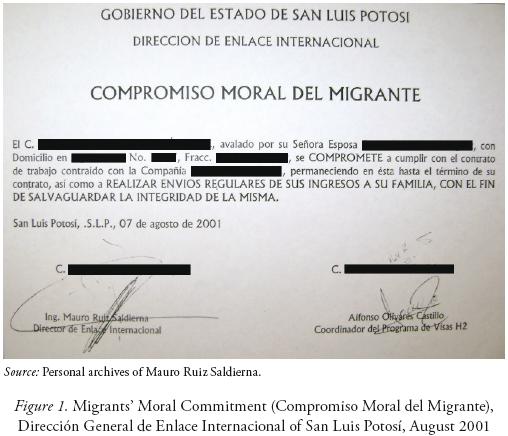

The DGEI required selected workers to sign a Migrants' Moral Commitment (Compromiso Moral del Migrante) which obliged them to engage solely in the work for which they had been hired, to "send regular remittances from their income to their families, in order to protect the integrity of the latter," and to return to Mexico within the agreed time limit (see figure 1). This document drawn up by the DGEI included the signatures of the migrants' wives, and in some cases of their mothers and children.

Efforts by the San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas governments to administer temporary employment for their citizens began at a meeting with U.S. government officials in the city of Monterrey, Nuevo León. Armando Elías Esparza representing Zacatecas, and Mauro Ruiz Saldierna representing San Luis Potosí, together with representatives from the states of Puebla, Hidalgo, and Guanajuato traveled to Monterrey, Nuevo León, to participate in the First Forum on H–2A and H–2B Work Visas.

From December 1999 to late 2000, the public agency for migrants in San Luis Potosí collaborated in sending over 300 workers with temporary employment visas to a meat packing firm in Corpus Christi, Texas, and to landscaping companies in Missouri, Maryland and Colorado.13 According to Mauro Ruiz, former director of the DGEI, thanks to the Migrants' Moral Commitment that he designed, only one of the more than 300 workers sent from San Luis Potosí deserted.

To explain how state governments intervened in the administration of H–2 visas, it is important to describe the way they work. According to Mónica Verea (2003:133), the H–2 visa programs began during the Second World War when the Allies needed cheap labor. She notes that in 1952, Public Law 283 was passed establishing "the H–2 category of non–immigrants for the first time, [...] it authorized the temporary admission of unskilled foreign workers on a small scale without special approval from Congress" (Verea, 2003:146–147).

This visa category is sub–divided into H–2A and H–2B. On the one hand, H–2A visas are designed for farm workers for a period of not longer than eleven months with the possibility of renewal. According to Ángel Torres Mendoza (2007:143–144), from the Centro de Asesoría Jurídica y Sindical Valentín Campa, several Mexican workers with H–2A visas have engaged in the production of tobacco in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and Kentucky; Christmas trees in Georgia, Tennessee, New York and Atlanta; corn in Indiana; onions in Georgia and Virginia; other vegetables in Mississippi, Georgia and Washington; and apples in New York. Using information from the Inter–American Institute of Migration and Labor, this author has also identified the two largest foreign contracting companies that provide Mexican farm labor for the U.S. market: Del–Al Associates, Inc. or Álamo Partners (with offices in McAllen, Texas; Monterrey, Nuevo León; and San Luis Potosí, S. L. P.) and Manpower of America (with its operating center in Monterrey, Nuevo León, and offices throughout other cities in Mexico) (Torres Mendoza, 2007:144).14

On the other hand, H–2B visas are intended for temporary non–farm workers. Mexicans accounted for 27 per cent of all these visas in 2001, for which work certification is required and admission is limited (Verea, 2003:133). This type of visa is provided for unskilled workers. In May of 2008, Los Angeles Times (Gaovette, 2008) reported that given the bureaucratic difficulties faced by entrepreneurs interested in hiring workers with H–2B visas, the Labor Department began re–writing the operating rules in order to streamline the program.

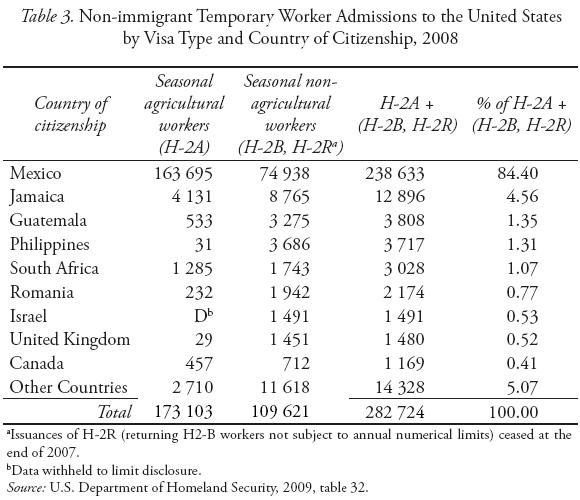

According to data from the Department of Homeland Security, in 2008, Mexico obtained by far the largest number of temporary visas for seasonal agricultural workers (H–2A) and seasonal non–agricultural workers (H–2B and H–2R) (see table 3).

The Secretaría del Migrante in Michoacán has also made an effort to administer temporary employment in the United States. On March 3, 2008, the state government signed a collaboration agreement with United Farm Workers (UFW)—a union founded by César Chávez—to enable peasants from extremely marginalized municipalities to engage in farm work in the United States with H–2A visas. The document was signed by the recently elected governor Leonel Godoy and Arturo Rodríguez, president of UFW (Correa, 2008). Another effort to administer temporary employment abroad for Michoacanos is that of the Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico in Michoacán which in collaboration with the Servicio Nacional de Empleo participates in hiring temporary farm workers through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program established between the Canadian and Mexican governments in 1974.

Conclusions

With the incorporation of state governments, emigration policy in Mexico has rapidly developed and become increasingly complex since its inception at the federal level in the early 1990s. In this respect, Mexico has established government institutions at the federal, state and municipal levels to attempt to manage the enormous diaspora of eleven and a half million people now residing in the United States. Since 2006, these migrants send Mexico approximately 25 billion dollars annually in family remittances, constituting the second largest source of foreign income after oil revenues.

Nowadays, most states in Mexico have a public agency for emigrants; only eight of the 32 states lack this type of government institution. This article has shown the emergence of a state emigration policy in Mexico that was due to the confluence of three factors. First, the 1990 initiative of the Foreign Affairs Ministry proved crucial in recommending the creation of offices in each state to provide services for communities abroad. The second factor was the demands on the part of organized migrants for state governments to provide services and solutions to their problems. These groups include the HTAs and federations of Mexican immigrants residing in the United States, and former bracero organizations fighting for the reimbursement of their savings that had been held back by employees during the first part of the Bracero Program. The third factor was the interest of governors, local congresses and political parties at the state level who regarded international migrants as a new electorate. This factor includes the "cascade effect" which consists of replicating the activities states are undertaking in relation to migration. The exchange of experiences between state governments through the National Coordinator of Migrant Service Offices (Conofam) was crucial in this process.

The existence of state public agencies for international migrants in Mexico also reflects the inability of the federal government to cope with regional diasporas with such heterogeneous histories, sociocultural profiles and political cultures. The question that arises is to what extent the decentralization of emigration policy has led to more effective management. State governments have a greater capacity than federal government to approach emigrants in their communities of origin, as shown by their participation in the repatriation of the deceased and the management of temporary employment abroad. State governments serve a smaller population than federal government and also have more suitable mechanisms for establishing closer links with their emigrants in the United States. For example, migrants in the United States organized into HTAs have formed federations at the state level that establish more direct and fluid communication with both state and municipal administrations.

Before it had a migrants' agency with its own range of services, Zacatecas had a collaboration program with migrants' organizations which for several decades had invested in basic infrastructure and social programs on its own account. Other governments, e.g., Guanajuato and Jalisco, were also interested in attracting remittances from their migrants and channeling them into sending communities. Unlike these cases, since 1992, there has been a state government agency in Michoacán that was primarily concerned with the repatriation of the deceased but also provided support for migrants and their families. In comparison with other states, the Michoacán agency has the largest budget and an administrative structure with greater hierarchy.

Lastly, just as Aristide Zolberg (2006) considers that immigration policy is a key instrument in nation–building, emigration policy performs this function by extending the nation beyond its borders in the Mexican case. This vision is reflected in the Plan nacional de desarrollo presented by the Mexican federal government in 1995 when it declared that "the Mexican nation exceeds the territory contained by its borders." Consequently, state governments such as those of Zacatecas, Michoacán and San Luis Potosí, have gone beyond national borders to govern their citizens abroad.

References

Aguayo Quezada, Sergio, ed., (2007), El almanaque mexicano 2007, México, Aguilar. [ Links ]

Alanís, Fernando (2006), "Que se vayan y se queden allá: La política mexicana hacia la migración a Estados Unidos," in Jorge A. Schiavon, Daniela Spenser and Mario Vázquez, eds., En busca de una nación soberana: Relaciones internacionales de México, siglos XIX y XX, México, Acervo Histórico Diplomático–Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, pp. 351–384. [ Links ]

Alarcón, Rafael (2006), "Hacia la construcción de una política de emigración en México," in Carlos González Gutiérrez, coord., Relaciones Estado–diáspora: Aproximaciones desde cuatro continentes, México, Porrúa/Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, pp. 157–179. [ Links ]

Asis, Maruja (2006), "Desenvolviendo la caja de balikbayan: Los filipinos en el extranjero y su país de origen," in Carlos González Gutiérrez, coord., Relaciones Estado–diáspora: Aproximaciones desde cuatro continentes, México, Miguel Ángel Porrúa/ Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, pp. 23–51. [ Links ]

Badillo, David A. (2001), "Religión y migración transnacional en Chicago: El caso de los potosinos," in Fernando Alanís Enciso, coord., La emigración de San Luis Potosí a Estados Unidos: Pasado y presente, México, El Colegio de San Luis/Senado de la República, pp. 117–141. [ Links ]

Brand, Laurie (2006), "Marruecos: La evolución de la participación institucional del Estado en las comunidades," in Carlos González Gutiérrez, coord., Relaciones Estado–diáspora: Aproximaciones desde cuatro continentes, México, Miguel Ángel Porrúa/Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, pp. 99–136. [ Links ]

CESOP (2006), "Contexto nacional," Migración, frontera y población, México, Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión, June 8. [ Links ]

Conapo (2006), Mexico–United States Migration: Regional and State Overview, México, Secretaría de Gobernación/Consejo Nacional de Población. [ Links ]

Cornelius, Wayne A. and Jessa M. Lewis (2007), Impacts of Border Enforcement on Mexican Migration: The View from Sending Communities, La Jolla, California, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies/University of California at Diego. [ Links ]

Correa Evaristo (2008), "Convenio de gobierno del estado y la United Farm Workers beneficiará a jornaleros", La Jornada de Michoacán, Morelia, Michoacán, May 29. Available at <http://www.lajornadamichoacan.com.mx/2008/05/29/index.php?section=municipios & article=012n1mun> (last accessed on March 1, 2010). [ Links ]

Durand, Jorge (2004), "From Traitors to Heroes: 100 Years of Mexican Migration Policies," Migration Information Source, Migration Policy Institute. Available at <http://www.migrationinformation.org/Feature/display.cfm?ID=203> (last accessed on March 1, 2010). [ Links ]

Durand, Jorge and Douglas Massey (2003), "Regiones de origen," Clandestinos. Migración México–Estados Unidos en los albores del siglo XXI, México, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, pp. 63–96. [ Links ]

Escala Rabadán, Luis (2005), "Migración internacional y organización de migrantes en regiones emergentes: El caso de Hidalgo," Migración y Desarrollo, first semester, num. 4, pp. 66–88. [ Links ]

Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l'Homme (2008), "United States–Mexico Walls, Abuses, and Deaths at the Borders: Flagrant Violations of the Rights of Undocumented Migrants on their Way to the United States," num. 488/2. Available at <http://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/USAMexiquemigran488ang.pdf> (last accessed on March 1, 2010). [ Links ]

Fernández de Castro, Rafael, Rodolfo García Zamora and Ana Vila Freyer, coords., (2006), El Programa 3x1 para Migrantes. ¿Primera política transnacional en México?, México, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Fernández de Castro, Rafael et al., coords. (2007), Las políticas migratorias en los estados de México: Una evaluación, México, Cámara de Diputados, LX Legislatura/Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Figueroa–Aramoni, Rodolfo (1999), "A Nation Beyond Its Borders: The Program for Mexican Communities Abroad," Journal of American History, vol. 86, num. 2, September, pp. 537–544. [ Links ]

Fitzgerald, David (2009), A Nation of Emigrants. How Mexico Manages Its Migration, Berkeley, California, University of California Press. [ Links ]

Fuentes, Jazmin and Olivia Garcia (2009), "Coyotaje: The Structure and Functioning of the People–Smuggling Industry," in Wayne A. Cornelius, David Fitzgerald and Scott Borger, eds., Four Generations of Norteños: New Research from the Cradle of Mexican Migration, La Jolla, California/Boulder, Colorado, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies/Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 79–100. [ Links ]

Ganlen, Alan (2008), "The Emigration State and the Modern Geopolitical Imagination," Political Geography, num. 27, pp. 840–856. [ Links ]

Gaovette, Nicole (2008), "New Work Visa Rules to Cut Bureaucracy", in The Nation, Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, California, May 22. Available at <http://articles.latimes.com/2008/may/22/nation/na–immigration22> (last accessed on March 1, 2010). [ Links ]

García y Griego, Manuel (1988), "Hacia una nueva visión de los indocumentados en Estados Unidos," in Manuel García y Griego and Mónica Verea Campos, eds., México y Estados Unidos frente a la migración de los indocumentados, México, Coordinación de Humanidades/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

García y Griego, Manuel (2006), "Dos tesis sobre seis décadas. La emigración hacia Estados Unidos y la política exterior mexicana," in Jorge A. Schiavon, Daniela Spenser y Mario Vázquez eds., En busca de una nación soberana: Relaciones internacionales de México, siglos XIX y XX, México, Acervo Histórico Diplomático, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (pp. 551–580). [ Links ]

García Zamora, Rodolfo (2006), "Migraciones internacionales y desarrollo en México: Tres experiencias estatales," in Rafael Fernández de Castro et al. coords., Las políticas migratorias en los estados de México: Una evaluación, México, Cámara de Diputados, LX Legislatura/Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas/Miguel Ángel Porrúa, pp. 157–170. [ Links ]

Goldring, Luin (2002), "The Mexican State and Transmigrant Organizations: Negotiating the Boundaries of Membership and Participation," Latin American Research Review, num. 37, pp. 55–99. [ Links ]

González Gutiérrez, Carlos, coord., (2006), Relaciones Estado–diáspora: Aproximaciones desde cuatro continentes, México, Miguel Ángel Porrúa/Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas. [ Links ]

Hollifield, James (2004), "The Emerging Migration State," The International Migration Review, vol. 38, num. 3, pp. 885–912. [ Links ]

Imaz, Cecilia (2006), La nación mexicana transfronteras. Impactos sociopolíticos en México de la emigración a Estados Unidos, México, Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociología/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Seminario de Política y Migración. [ Links ]

Irazuzta, Ignacio y Guillermo Yrizar (2006), "Gobernar la migración: Consideraciones y preguntas en torno al gobierno de los mexicanos en el exterior," in Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión Pública, La migración en México: ¿Un problema sin solución?, México, Cámara de Diputados, LIX Legislatura, pp. 173–216. [ Links ]

Izquierdo, Antonio and Sandra León (2008), "La inmigración hacia adentro: Argumentos sobre la necesidad de coordinación de las políticas de inmigración en un Estado multinivel," in Política y Sociedad, vol. 45, num. 1, pp. 11–39. [ Links ]

Jimenez, Maria (2009), Humanitarian Crisis: Migrants Deaths at the U.S.–Mexico Border, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of San Diego and Imperial Counties/Mexico's National Commission of Human Rights, October 1. Available at <http://www.aclu.org/files/pdfs/immigrants/humanitariancrisisreport.pdf> (last accessed on March 1, 2010). [ Links ]

Lestage, Fraçoise (2008), "Apuntes relativos a la repatriación de los cuerpos de los mexicanos fallecidos en Estados Unidos," Migraciones Internacionales 15, vol. 4, num. 4 , pp. 209–220. [ Links ]

H. Congreso del Estado de Michoacán de Ocampo (2008), Ley orgánica de la administración pública del estado de Michoacán de Ocampo, Morelia, January 9. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas et al. (1987), Return to Aztlán: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico, Berkeley, California, University of California Press. [ Links ]

Moctezuma Longoria, Miguel (2003), "La voz de los actores: Ley migrante y Zacatecas," in Migración y desarrollo, num. 1, October, pp. 1–19. [ Links ]

POEA (2005), OFW Global Presence: A Compendium of Overseas Employment Statistics, Mandaluyong City, Philippines, Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. Available at <http://www.poea.gov.ph/stats/OFW_Statistics_2005.pdf> (last accessed on June 6, 2009). [ Links ]

Ruiz Saldierna, Mauro (2008), "Memorias de un migrante. Antecedentes, iniciativas, satisfacciones y decepciones en la creación, organización y despegue de la oficina estatal de atención a migrantes del Gobierno del Estado de San Luis Potosí, 19972003," in Fernando Alanís Enciso, coord., ¡Yo soy de San Luis Potosí!... Con un pie en Estados Unidos, México, El Colegio de San Luis/Miguel Ángel Porrúa/Secretaría de Gobernación/ Consejo Potosino de Ciencia y Tecnología, pp. 187–212. [ Links ]

Schiavon, Jorge (2004), "La política externa de las entidades federativas mexicanas: Un estudio comparativo de seis federaciones," Integración y Comercio, year 8, num. 21, July–December, pp. 109–131. [ Links ]

Schmitter Heisler, Barbara (1985), "Sending Countries and the Politics of Emigration and Destination," The International Migration Review, vol. 19, num. 3, pp. 469–484. [ Links ]

Sisco, Jessica and Jonathan Hicken (2009), "Is U.S. Border Enforcement Working?," in Wayne A. Cornelius, David Fitzgerald and Scott Borger, eds., Four Generations of Norteños: New Research from the Cradle of Mexican Migration, La Jolla, California/Boulder, Colorado, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies/Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 41–76. [ Links ]

Smith, Michael P. (2003), "Transnationalism, the State, and the Extraterritorial Citizen," Politics and Society, vol. 31, num. 4, pp. 467–502. [ Links ]

Smith, Robert C. (2003), "Migrant Membership as an Instituted Process: Transnationalization, the State and the Extra–Territorial Conduct of Mexican Politics," International Migration Review, vol. 37, num. 2, pp. 297–343. [ Links ]

Taylor, Paul S. (1933), A Spanish–Mexican Peasant Community: Arandas in Jalisco, Berkeley, California, University of California Press. [ Links ]

Torres Mendoza, Ángel (2007), "La migración agrícola documentada de México a Estados Unidos: Un proceso de contratación ilegal en territorio nacional," in Cecilia Imaz, coord., ¿Invisibles? Migrantes internacionales en la escena política, México, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Políticas/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Sitesa, pp. 141–154. [ Links ]

United States Department of Homeland Security (2009), Yearbook of Immigration Statistic: 2008, Washington, D. C., U.S. DHS, Office of Immigration Statistics. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, M. Basilia (2006), "La instauración del 3x1 en Jalisco: El acomodo de los gobiernos estatales a una política adoptada por el Gobierno del Estado," in Rafael Fernández de Castro et al. coords., Las políticas migratorias en los estados de México: Una evaluación, México, Cámara de Diputados, LX Legislatura/Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México/Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas/Miguel Ángel Porrúa, pp. 139–156. [ Links ]

Velázquez Flores, Rafael (2006), "La paradiplomacia mexicana: Las relaciones exteriores de las entidades federativas," Relaciones internacionales, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, February–August. [ Links ]

Verea, Mónica (2003), "Las políticas sobre migrantes temporales en América del Norte," Migración temporal en América del Norte. Propuestas y respuestas, México, Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 123–179. [ Links ]

Vila Freyer, Ana (2007), "Las políticas de atención a migrantes en los estados de México: Acción, reacción y gestión," in Cecilia Imaz, coord., ¿Invisibles? Migrantes internacionales en la escena política, México, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Políticas/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Sitesa, pp. 77–105. [ Links ]

Yrizar Barbosa, Guillermo (2008) [master dissertation], "De la repatriación de cadáveres al voto extraterritorial: Política de emigración y gobiernos estatales en el centro occidente de México," Tijuana, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Yrizar Barbosa, Guillermo (2009), "Políticas migratorias e instituciones hacia los marroquíes en el extranjero: ¿Amenaza política o panacea transfronteriza?," Frontera Norte 42, vol. 21, July–December, pp. 53–77. [ Links ]

Zolberg, Aristide (2006), A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America, New York, Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Websites

Banco de México (Bank of Mexico [Banxico]), <http://www.banxico.org.mx/>. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población (National Council of Population [Conapo]), <http://www.conapo.gob.mx/>. [ Links ]

Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (Institute for Mexicans Abroad [IME]), <http://www.ime.gob.mx/>. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography [INEGI]), <http://www.inegi.gob.mx/>. [ Links ]

Non–Resident Keralites' Affairs Department (Norka), <http://www.norka.gov.in/>. [ Links ]

1 We are greatly indebted to Franchise Lestage, David Fitzgerald and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

2 Institute for Mexicans Abroad website, at <http://www.ime.gob.mx/> (last accessed on August 16, 2009).

3 Non–Resident Keralites' Affairs Department website, <http://www.norka.gov.in/> (last accessed on March 1, 2010).

4 It is important to note that before the participation of states governments in the financing of public infrastructure, during the 1970s Mexicans in the United States from states like Zacatecas or San Luis Potosí gathered funds to support small population nuclei such as ranchos, localities, towns and municipalities in their places of origin, in order to buy materials that will make it possible to provide public services, like distribute drinking water (Badillo, 2001:428).

5 Interview with Claudio Méndez, Morelia, Michoacán, February 2008. From January to March 2008, interviews were carried out with the directors and personnel of public agencies for migrants at the state level, mainly in the states of Michoacán and San Luis Potosí. We are grateful for the cooperation of both the Instituto Michoacano de los Migrantes en el Extranjero and the Instituto de Atención a Migrantes del Estado de San Luis Potosí.

6 Interview with Jesús Martínez Saldaña, Morelia, Michoacán, February 2008.

7 E–mail communication with Ventura Gutiérrez, May 2008.

8 The five states with very high marginalization according to Conapo estimates are Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Hidalgo, and Veracruz. In recent years, these states have experienced an increase in their migratory flows. As early as 2000, Guerrero and Hidalgo already had a high degree of migratory intensity (Conapo, 2000, "Índices de Marginación" and "Publicaciones en línea", <http://www.conapo.gob.mx> (last accessed on March 1, 2010).

9 The document states that they comprise the Asociación Nacional de Oficinas de Apoyo a Migrantes de la República Mexicana, as a "permanent organization that promotes the integral solution of the problems that lead to the migration phenomenon, both inside and outside the country, whose main aim being development with justICE and equity for Mexico's male and female migrants." We are grateful to Mauro Ruiz Saldierna, director of the Oficina Municipal para la Atención a Migrantes de San Luis Potosí in 2008 for providing us with a copy of this document.

10 In Morelos, governorship was handed over from the PRI to the pan on July 6, 2000.

11 Seventeen considerations comprise the Declaratoria de Puebla, including the following: encourage participation by the three orders of government; strengthen links with Mexicans in the United States to preserve their identity and language; provide job training for migrants and their families in their communities of origin to improve their income; launch health campaigns; promote productive projects in sending zones that will provide employment alternatives; acknowledge remittances as a "stability factor" in receiving areas; promote the creation of state centers or offices in "locations where there are concentrations of Mexican migrants inside and outside the country" in order to provide legal advice and support with emphasis on human rights; cooperation and rapprochement with federal government, the media and hometown associations.

12 Most of the information on this section is based on interviews with Mauro Ruiz Saldierna on February 2008 in San Luis Potosí, and with Armando Elías Esparza on May 2008 in Tijuana.

13 E–mail communication with Mauro Ruiz Saldierna, 12 June, 2008.

14 The study called "La migración agrícola documentada de México a Estados Unidos: Un proceso de contratación ilegal en territorio nacional" by Ángel Torres Mendoza (2007:141–154) deals with "the responsibility of the Mexican State and its governments in hiring Mexican farm workers to work abroad," highlighting the lack of policies that defend and protect international labor migrants. The author holds that temporary employment programs established between Mexico and the United States have violated the labor legislation of both countries.

Information about authors

GUILLERMO YRIZAR BARBOSA es licenciado en ciencia política por el Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey y maestro en desarrollo regional con especialidad en migración internacional por El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Fue estudiante de intercambio en la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona y becario del seminario de verano del Center for US–Mexican Studies de la Universidad de California en San Diego. Es coautor, con Ignacio Irazuzta, del ensayo "Gobernar la migración: Consideraciones y preguntas en torno al gobierno de los mexicanos en el exterior", en La migración en México: ¿Un problema sin solución?, México, Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión Pública, Cámara de Diputados/LIX Legislatura, 2006.

RAFAEL ALARCÓN es director del Departamento de Estudios Sociales de El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Obtuvo el doctorado en planeación urbana y regional por la Universidad de California en Berkeley. Pertenece al Sistema Nacional de Investigadores en el nivel II y fue director fundador de la revista Migraciones internacionales. Entre sus publicaciones más recientes está "The Free Circulation of Skilled Migrants in North America", en Antoine Pécoud y Paul de Guchteneire (edits.), Migration without Borders. Essays on the Free Movement of People, París/Oxford/Nueva York, UNESCO Publishing/Berhahn Books, 2007.