Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Migraciones internacionales

On-line version ISSN 2594-0279Print version ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.4 n.3 Tijuana Jan./Jun. 2008

Artículos

Migrant–Local Government Relationships in Sending Communities. The Power of Politics in Postwar El Salvador

Xiomara Peraza*

*Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana–Iztapalapa. Dirección electrónica: xiomara.peraza@gmail.com

Fecha de recepción: 7 de marzo de 2007

Fecha de aceptación: 17 de septiembre de 2007

Abstract

This article analyzes refugee political transnationalism in El Salvador. It assesses the domestic or homeland component of migration history in this Central American country by focusing on the role of both local governments and specific communities. Moreover, it considers differences between areas that vary in terms of the level and type of political organization during and after the civil war, the levels of international migration, population concentration in settlement areas in the United States, and the types of relationships between local authorities and both collective and individual migrants. Studying and comparing political transnationalism may help explain why transnational initiatives progress in some settings but not others. This study considers some of the factors that should be taken into account in order to understand transnational activities in sending communities. The finding show that partisan politics constitute an element to be studied as part of the conditions that may enhance or limit relationships between migrants and local governments in postwar El Salvador.

Keywords: Political transnationalism, migrant associations, postconflict, partisanship, sending communities.

Resumen

En este documento se analiza el transnacionalismo político en El Salvador y se explora el componente interno de la historia migratoria de este país centroamericano, con un enfoque en el papel tanto de los gobiernos locales como de comunidades territoriales específicas. Además, se consideran las diferencias entre áreas que varían en términos de su nivel y tipo de organización política durante y después de la guerra civil, los niveles de la migración internacional, la concentración de la población en áreas de destino en Estados Unidos, los tipos de relaciones entre las autoridades locales y los migrantes tanto colectivos como individuales. Estudiar y comparar el transnacionalismo político puede ayudarnos a explicar por qué las iniciativas transnacionales prosperan en algunos casos y no en otros. En este estudio se toma en cuenta sólo los factores que coadyuvan en el entendimiento de las actividades transnacionales en las comunidades expulsoras. Los resultados muestran que la política partidista constituye un elemento que debe ser estudiado como parte de las condiciones que afectan las relaciones entre los migrantes y los gobiernos locales en la etapa de posguerra en El Salvador.

Palabras clave: Transnacionalismo político, asociaciones de migrantes, posconflicto, partidismo, comunidades expulsoras.

Introduction1

In 2004, the right–wing party of El Salvador (The Nationalist Republican Alliance, ARENA) exploited the issue of migrants' remittances as one of the main features of its presidential campaign. This political party won the presidency for the fourth time in a row, despite the fact that six months before the election, the opposition —Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional, FMLN— was leading the race. In its campaign, ARENA contacted U.S. representatives who warned Salvadoran voters against the potential victory of the left (the ex guerrilla group and main opposition party). There was one specific TV spot showing a family group reading a letter from a relative living in the U.S. The letter said that the remittance they had just received might well be the last if the FMLN won the presidential election. The message was clear for both Salvadoran migrants and nonmigrants (the actual voters) and shows just how important the issue of migration is for Salvadoran society.2

The purpose of this essay is to explore the domestic or homeland component of this phenomenon by focusing on the role of both local authorities and communities, and considering differences between areas that vary in terms of the level and type of political organization during and after the civil war, the levels of international migration, population concentration in areas of settlement in the U.S, and the types of relationships between local governments and migrants at the collective and individual level.

Studying and comparing transnationalism, particularly sub–national contexts characterized by U.S.–bound migration, may help explain why transnational initiatives develop into complex networks (such as the cooperative work between local governments and hometown associations —HTA—, for example) in some settings, but not others. I do not intend to explain the formation of HTA. In fact, my main objective is to explore sending communities and the scenarios in which relationships between collective or individual migrants and local governments may emerge or become more intense. At some point, I do discuss what may facilitate the formation of HTA with the purpose of putting forward ideas (arguable as they may be) drawn from my comparative analysis.

This topic is particularly relevant nowadays because of the tendency of government agencies, non–governmental and international organizations, as well as scholars to talk about migrants and their contributions to their home countries (especially economic ones) as if they were a magic solution to underdevelopment. My contention is that this perspective remains open to multiple questions and that remittances should not be so hastily prescribed as the cure for all the problems in poor countries. While recognizing the potential of transnational networks to contribute to local development, one should consider the scenarios where the remedy might work (all types of remittances, in this case) and where it might not. Specifically, one should analyze where cooperative endeavors between local governments and migrants might be feasible and where there are no conditions for this. Once a diagnosis has been obtained, then decisions can be made regarding the potential contribution of transnational networks to fostering economic development processes in the migrant–sending regions of El Salvador. If conditions are not optimal for these links then one should look for alternative options that are more effective and more structural.

I examined four Salvadoran municipalities and conducted a comparative analysis of the conditions that may help or hinder the development of relationships between local governments in hometown communities and migrants settled in the U.S. My essay supports those arguing in favour of taking into account the situation of people coming from conflict zones, whether they are officially recognized as refugees or not. This is explicitly framed as an analysis of transnationalism among forced migrants.

Theoretical framework

Movements of people across borders have created different types of remittances, which play a key role in both producing and receiving countries (Levitt, 1998; Goldring, 2003). Perspectives on the role of these formations and their agency may differ from one scholar to another (Glick–Schiller and Fouron, 1999; Mahler, 1998; Landolt et al., 1999; Delgado and Rodríguez, 2001; Smith, 2003; Paul and Gammage, 2004), yet transnational migrant networks have created spaces for individuals and social movements to be recognized as influential not only in their countries of origin but also in their countries of reception.

High levels of international migration per se do not explain the forms or intensity of transnational activities (Guarnizo et al., 1999). Salvadorans are engaged transnationally, and my analysis identifies some of the variables that shape this process, especially with respect to political transnationalism.

A good example of political transnationalism can be found in the contributions of HTA to sending communities. These migrant organizations are usually created to cooperate with their towns of origin. They start as economic contributors and often become important in the local political structure, especially when they establish formal relationships with local entities (whether governmental or non–governmental). As a result, what may have started as a transnational economic practice often develops into a political one.3 Progressively, the influence of these migrant organizations appears in different fields at the same time (cultural, religious, etc.). This is also observed in individual migrants, who contribute economically to their communities. Given this connection between transnational practices, I consider that the relationships between migrants and local governments are issues that should be studied as political transnationalism (among others, see Levitt, 1998; Goldring, 2003).

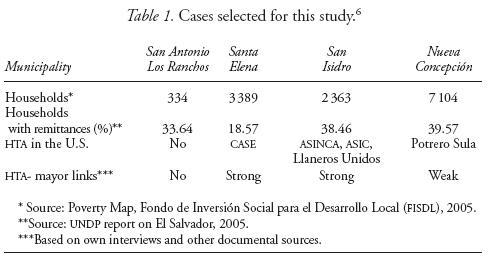

Transnationalism in general varies in El Salvador at the subnational level. If one considers two municipalities with similar levels and histories of out–migration, the local processes generated may not follow the same path. Take Nueva Concepción, a Salvadoran municipality where 33.64 percent of the population receives remittances, and Santa Elena, where 18.57 percent does. Migrants from the former have not created an HTA yet (at least not in its main urban area or casco urbano) and the municipality has not developed links with the diaspora from this community, while the latter has one of the most active migrant organizations and until 2006 had accomplished important projects in conjunction with the mayor's office. This paper attempts to understand these differences between Salvadoran municipalities and to provide some explanations for them.

Scholars have noted that the existence of a continuing flow of out–migration and large numbers of migrants does not suffice to make transnational links and actions develop. Guarnizo and his colleagues claim that "transnational relations and activities do not follow a linear path and are not necessarily and inevitably a progressive process" (1999:391). They based this conclusion on the study of Colombians migrants in New York and Los Angeles. The effects of transnational processes, they say, should consider the combination of several contextual and group factors; my analysis explores some of them. In particular, I focus on the locality of origin, exit conditions and local government–migrant relations, including political conflict or affinity.

Guarnizo and his colleagues suggested a more general approach, and focused mainly on sending and reception state–level conditions, whereas I am concerned with the regional and local level of sending countries in order to explain local variation. I am interested in the comparative study of different territorial communities where we can see diverse outcomes in terms of the existence or absence of political migrant activity at the individual and collective level. Variation can be seen in the types of relations (their dearth, weakness or strength) that develop between local officials and migrants.

Existing research on forms of transnational organization has focused on determinants such as exit and reception contexts, migration history, migrants' social capital, and their ties to their countries and places of origin (Portes and Böröcz, 1989; Guarnizo et al., 1999). The literature has also pointed to other factors that may lead to the formation of HTA, namely the rural origin of a migrant community abroad, its long migratory tradition, its tendency to settle progressively in the U.S., as well as the participation of community leaders and the dynamic role of the government in the sending country to foster relations with its population abroad (Alarcón, 2002). I also explore some of the aforementioned determinants or factors but in a different way, as part of the context where transnational political networks take place.

This essay contributes to work on transnationalism that considers subnational regional and municipal differences in conflict and post–conflict situations, a subject that the U.S.–based literature has left relatively unexplored.4 In particular, I analyze the relationship between the history and volume of migration and remittances, patterns of domestic migration and how this shapes local approaches to territorial membership and belonging, forms of political organization during and after the civil war, and local governments' contemporary policies and initiatives towards migrants.

The literature on transnationalism I have reviewed shows that although certain scholars recognize the importance of assessing subnational contexts in the study of collective migrants and home communities, they have focused on provincial comparisons rather than regional or similar comparisons. Thus, the field has remained relatively unexplored (Mahler, 1998; Goldring, 2002; Bauböck, 2003).

In the study of migratory policies, most scholars have focused on the upper levels of government such as the Mexican case where the analysis of the federal and state government and its involvement in the issues affecting Mexican emigrants is dominant (Guarnizo, 1997; González, 1999; Sherman, 1999; Goldring, 2002; and Smith, 2003). The literature studying other countries has followed a similar pattern, focusing on the national level (Levitt and De la Dehesa, 1999; Rosenblum, 2002; Guarnizo, 1997; Lungo, 2002; Glick–Schiller and Fouron, 1999; Itzigsohn, 2000).

The study of "substate polities" has rarely been approached and becomes all the more important when we consider what Bauböck (2003) has said about local and regional levels of government as being "more responsive to migrants' transnational interests and identities than institutions and actors at the independent state level" (707).

Most of the U.S.–based studies on El Salvador I read have not addressed the relationship between migrant organizations and municipal governments in detail either, although the importance of this level of analysis has been highlighted by some of them (Andrade and Silva, 2003; Landolt et al., 1999; Landolt, 2003; Lungo, 2002; Popkin, 2003; Paul and Gammage, 2004). The experience of territorial "sending" communities has been examined by some Salvadoran scholars. I would like to mention four of the studies I have found, which focused on specific municipalities in El Salvador.

First, Blandón explores the institutional capability of Ilobasco to take advantage of migration flows (Blandón, 2002). A second study looks at the relationship between the migrant population and a wide range of home community agents, and its contribution to local development in Santiago Nonualco (Morales and Castillo, 2005). The third study conducted a comparative analysis of three hometowns: San Sebastián, Suchitoto y Tejutla, where the authors examined the contribution of Los Angeles–based migrant organizations to the development of their places of origin (De León and Rodríguez, 2005). The last one refers to Mercedes Umaña in Usulután and San Sebastián, located in San Vicente (Mora, 2005). The study intended to show the emergence of new social actors as a result of international migration and their indirect impact on public decision–making in sending communities through the establishment of links between local and transnational actors.

None of the above has focused on the municipalities and their links with migrants, which is the field I explore in the following pages. I mention these studies here, because my research was framed as a contribution to this kind of municipal–level research and I discuss some of their findings later on.

While framing itself as transnational, much of the U.S.–based literature concentrates on the migration history and conditions of settlement of transmigrant groups. The role of sending states is studied in relation to their nationals abroad and how state intervention has the potential to enhance, leverage or block these transnational networks. The locus always seems to be outside [except for a few studies such as Mahler (1998) and the cases in the paragraph above], rather than in the sending communities, a scholarly tendency that I consider problematic.

This can be seen in the way Salvadoran hometown associations have been approached. According to the 2005 UNDP report on El Salvador, international migration has generated various local dynamics in this country. Hometown associations themselves are largely heterogeneous in terms of both their organizational capacity in the U.S. and their ability to conduct their initiatives in their places of origin (Paul and Gammage, 2004). The key, according to UNDP, is to coordinate migrant organizations with local institutions, so that the sustainability of the development process can be guaranteed and the dispersion of efforts avoided.

The UNDP claims that translocal processes, participation and negotiation are needed to make these initiatives work. I do not question the potential of such networks for local development in the sending communities. However, I am concerned about the fact that UNDP and the literature I have reviewed show a limited interest in the study of the realities of those hometown communities involved in these diverse dynamics.

My research therefore focuses on four municipalities (described in detail later on). My contention is that local government–migrant relations should be studied by considering particular details and circumstances at the level of each sending community in order to understand what encourages the emergence or lack of these relations. By doing this, we may realize that it is not entirely necessary to identify general patterns in this analysis. Instead, our attention should focus on the historical and conjunctural processes that have developed or are developing at the subnational level.

The bulk of the literature confirms the existence of variation in the levels and modalities of engagement between the migrant and non–migrant population in El Salvador (among other, see Popkin, 1997; Landolt, 2003; Andrade and Silva, 2003; Paul and Gammage, 2004). However, they do not present comparative analyses to explain this variation. Furthermore, in considering the explanatory factors behind such variation, politics is usually overlooked in the model.

As entities involved with the development of their home communities, Salvadoran HTA are seen as apolitical (my findings called this statement into question, as discussed later in this essay) in terms of their affiliation to political parties in the country of origin (Popkin, 1997). Popkin concluded that, by being apolitical, these groups have been able to build alliances with various sectors in El Salvador, including municipal authorities. To explain this, we should look at local circumstances, which are crucial to my study and have changed considerably since Popkin published his study in 1997.

Addressing the role of hometown associations in their country of origin, Paul and Gammage (2004) suggest that pre–existing political ties are a fundamental issue in the study of community development in El Salvador. However, the authors do not provide any further explanations of such ties and their impact on the type of relations developed between migrant organizations and municipal authorities, for instance. I argue that it is important to formulate even preliminary explanations for this.

The last aspect I would highlight at this point is the importance of considering conflict and post–conflict situations in the analysis of transnational activities. What is known as transnationalism from below and from above developed intensely in El Salvador after 1992, when the civil war had ended. Salvadorans left their country in droves during the 1980s mainly because of the war, which is an aspect I am trying to examine in–depth.

Based on the experiences of Bosnians and Eritreans, Al–Ali and his colleagues (2001a) have stressed the importance of the historical context in the understanding of 'emerging transnational practices' among refugees. A history of labor migration was significant in the case of Bosnian refugees who settled in the U.K. and the Netherlands, while the historical development of transnational mobilization for the war effort was crucial among Eritreans refugees in the U.K., who fled their country during the struggle for independence. Those who became refugees because of the conflict with Ethiopia have experienced international migration differently and features of transnationalism have appeared among them, although they cannot yet be considered a transnational community (2001a:632). Overall, the authors argue for the importance of considering the following factors in order to account for different patterns of transnationality: state policy, the context of flight, historical antecedents, and the dominance of particular ideological, moral or cultural positions (2001a:595).

These factors are also relevant to the study of international migration among Salvadorans, especially because massive migration occurred in this Central American country at the beginning of the civil war. At that time, regional and local migration was also considerable, and this movement in different directions also changed territorial communities locally (some evidence is shown in the four cases I explore later on) as well as the type of relationships that developed between migrants and their hometowns.

Research objectives and method

Given the research gaps presented so far, the first objective of my study is to identify key factors that encourage or discourage the development of transnational ties and engagement (as indicated by HTA and individual migrants). These include the volume and temporal history of migration, migrant concentration in U.S. sites in order for networks to develop, hometown population size and immigration, nativity and territorial membership. The second objective is to point to some factors that may explain the existence or absence of strong links between individual and collective migrants and local authorities. These include the impact of the civil war and its aftermath (including level of internal conflict and trust), political organization and partisan tendencies and sympathies.

There are studies showing how influential Salvadoran migrant organizations have become in their hometown communities (see UNDP, 2005; Paul and Gammage, 2004; Popkin, 2003; Andrade and Silva, 2003). However, as noted earlier, there is insufficient information explaining why relationships between the migrant community and the municipality do or do not take place. Seeing the need to take the analysis of this phenomenon further, I chose the qualitative approach and the case study research strategy.

The key aim here is to gain familiarity with the ways in which different hometown communities relate to their migrants, and vice versa. Specifically, this study seeks to highlight the role of one of the components of the Salvadoran transnational networks: local authorities (represented by the municipality) and hometown communities (represented by members of different ADESCO).5 Elected municipal authorities and community leaders closely related to the former constitute primary sources, because this research seeks to analyze the role played by entities already institutionalized with a certain (albeit arguable) level of representativeness.

I intended to obtain insights into specific municipalities as administrative–districts, and the role of mayors in the development of transnational networks, because they constitute important, powerful local entities. As such, they allow for both the institutionalization of transnational ties and the use of remittances (be they individual or collective) in initiatives that benefi t the community as a whole, transcending the family/individual level of influence. I acknowledge the importance of studying the different components of transnationalism. For this reason, I gained insights from a variety of sources with information on both receiving and sending states.

As seen in Table 1, these cases are heterogeneous in terms of their population size, the existence of migrant organizations in the U.S., and the existence of institutional links between migrants and municipal authorities. What makes them similar is the level of international migration, which is estimated on the basis of the percentage of households that receive remittances from their relatives abroad in each municipality. Using purposive sampling, I chose four municipalities:

This study considers subregional differences in conflict and post–conflict situations. The four municipalities I chose were affected by the civil war in different ways and levels, as can be seen from their migration patterns and local development.

There were three recent studies exploring practically the same topic of my essay but in different municipalities and comparisons did not seem to be their key objective (Mora, 2005; De León and Rodríguez, 2004; Morales and Castillo, 2005). Their findings have been analyzed here by isolating the themes/items that matched those I examined in my research.

Differences and similarities between municipalities

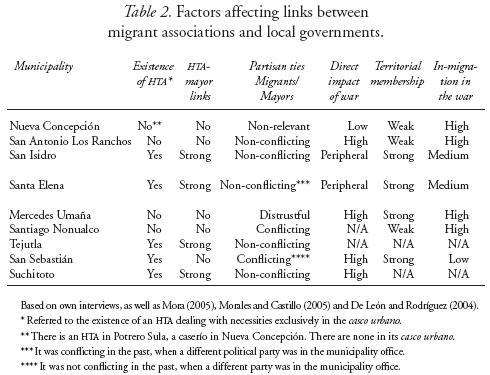

This section of my study discusses differences and similarities identified in the four cases researched and the municipalities investigated by Mora (2005), De León and Rodríguez (2004) and Morales and Castillo (2005). Overall, I found the following characteristics shown in Table 2.

In the table, I highlight the findings on migrant associations because they show how variable their relationships are to local governments. In each of the hometowns, the data from both the interviews and documents were classified and interpreted on the basis of the following general topics: a) levels of international migration and population concentration in areas of settlement in the U.S.; b) political organization and the influence of the civil war in terms of migration movements; and c) existence/absence of collective migrants–home community links at the subnational level and their importance for local development.

Levels of international migration and population concentration in areas of settlement in the U.S.7

The cases included in Table 2 showed variation in the levels of international migration. No direct relation between this category and migrant–local governments' links can be drawn from my findings. However, this is one of the determinants of HTA formation identified in the literature on transnationalism and this study confirms this proposition. In Table 2, the percentage of households receiving remittances from relatives abroad ranged from 11.6 in Suchitoto to 39.6 in Nueva Concepción (UNDP, 2005). The existence or absence of an HTA does not depend on these numbers. Nueva Concepción has the highest rate of remittances among the localities in Table 2, but has no HTA or any contacts between the municipality and the migrant community in the casco urbano.

There is a migrant organization in Potrero Sula, a small caserío in Nueva Concepción, which has been unable to build institutional relations with the municipality, even though it has made important contributions to its community school, church, health center and other entities. Individual migrants have not been able to establish significant contacts with the mayor's office either. Manuel Landaverde, secretary of the municipality, is not aware of any interaction between the mayors' office and the migrant community in the last decade: "La Alcaldía no ha trabajado con ellos... por decir, vamos a viajar a los Estados Unidos a hacer una asociación y que esta asociación pueda realizar eventos o cualquier cosa allá para que de alguna manera pueda mandar esa remesa y ayudar a las comunidades. No, eso no se tiene".8

Two factors seem to be playing a role in the absence of a migrants' association in the urban area of Nueva Concepción: its large population size (of the eight municipalities analyzed here, it is the second most highly populated) and its high in–migration levels during the civil war, which probably weakened the migrants' territorial membership in this case (Lungo and Kandel, 2002; Rodríguez, 1997). Landaverde says that

Hay mucha gente que vive acá, pero que no es originaria de acá... sino que se vinieron a poblar acá cuando la época del conflicto armado... Y, por ejemplo, le puedo mencionar gente de Arcatao, de Nueva Trinidad, de San José Cancasque... Es decir, todos aquellos pueblos que están en la parte oriente de Chalatenango, o vecinos de Honduras, de ahí hay muchas personas que han venido a establecerse acá...

In my study, Suchitoto has the lowest rate of international migration and its HTA has developed links with different players at the local level. This inverse relationship is consistent with Guarnizo et al. (1999), because I found that there is no need for large groups of migrants to get organized and start helping their places of origin, given that even small groups of Salvadorans have started important organizations while living abroad.

On the other hand, the fact that former residents of these municipalities are concentrated in one or two U.S. cities does not guarantee the existence of individual migrant–local government activities either. I did not find statistical data on the level of population concentration in areas of settlement in the US and the numbers available for some regions are always limited because of the high levels of undocumented migration to the north. Nonetheless, from my interviews, it became evident that in all these cases the migrant population was presumably concentrated in just a few U.S. cities.9

There were cases where this element was important (Santa Elena, San Isidro, for example). On the other hand, as noted, San Antonio Los Ranchos and Nueva Concepción surely have significant groups of migrants living in the same cities in the U.S., yet none of the municipalities have established institutional relations with the migrant community and hometown associations have not been created.

Although migrants may be concentrated in a few U.S. sites, HTA are not necessarily formed, because there might be some factors linked to their history of migration preventing collective transnational activities: territorial membership to home communities, for example, which was weakened due to different dynamics resulting from the civil war (as in the case of Nueva Concepción, Santiago Nonualco and San Antonio Los Ranchos). In these three municipalities, the level of in–migration due to the twelve–year conflict (see Table 2) changed the population's concept of belonging to its hometown.10

In San Antonio Los Ranchos, we have to consider the fact that massive international migration occurred relatively recently (in the mid–1990s), whereas in Nueva Concepción and Santiago Nonualco, settlement in the U.S. has been well–established enough for migrants to develop collective transnational initiatives. However, this has not happened. Neither high levels of out–migration nor long periods of settlement in the U.S. guarantee the emergence of diaspora organizations. Migrant concentration in areas of settlement is not sufficient either. A combination of these factors and others might shed more light on collective transnational networks.

Political organization and the influence of the civil war in terms of migration movements

San Antonio Los Ranchos differed from other municipalities in terms of the level of community political organization, which was built in the middle of the war.11 Most of its current inhabitants12 were displaced from their hometowns and then became refugees in Honduras until they returned to El Salvador at the end of the 1980s to settle in San Antonio Los Ranchos (Lungo, Serarols and Sintigo, 1997). Yet pre–existing political ties in this case have not translated into complex transnational networks like those seen in other places in El Salvador. Their tradition of organization might be weakening, said my informants, but still plays an important role in the solution of their social and economic problems. Wilber Mejía,13 a member of the community committee, expresses this in the following terms:

Primero, en Mesagrande [Honduras], por ser refugiados, todos nos venimos para acá organizadamente, nadie vino a la fuerza. Y aquí [El Salvador] estaba la guerra y tuvimos que organizarnos también porque una sola persona no hacía nada y venían los soldados y se lo podían llevar y lo mataban, pero la misma gente se organizaba para ir al cuartel y ver qué sucedía; si había algún herido [por los combates] se tocaba la campana de la iglesia y toda la gente salía a ayudarlo. Así sucede hoy... Pero la gente no pierde de vista lo pasado; hoy seguimos organizados pero no como antes. La gente se ha hecho muy cómoda; sí participa, pero no como antes.

The community's history during and after the civil war has created strong links between its people and these ties, reflected in different arenas, especially that of partisan politics, may have established the conditions for harmonious relations between the migrant population and the municipal authorities through informal contacts (for instance, groups of migrants have given money to rebuild the community's church and for the electric wires laid in the community). In fact, the incumbent mayor, José Serrano, is even promoting the creation of a hometown association in the U.S. According to him, "hay contactos con las familias de los migrantes, ya hay un esfuerzo de formar comités... Ellos han contribuido para la reconstrucción de la iglesia y han puesto algún tesorero para enviar el dinero a esa persona, también se ha pedido a los familiares para que les soliciten para las fiestas patronales y de la repoblación."

In contrast, such a tradition of political organization has never existed in Nueva Concepcion. Transnational networks in its casco urbano have never transcended the family/friend level. The mayor's office is not engaged in any project with migrants. The importance of developing relations with the migrant population, which is already so crucial in the economy of the households in this town, is barely acknowledged. This is so despite the fact that the municipality has missed two opportunities to get financing from the governmental program Unidos por la Solidaridad (similar to the Mexican tres por uno) for infrastructure projects due to the lack of a migrant counterpart.

The Salvadoran civil war itself and the level and type of political organization during and after it were factors that I regard as crucial in understanding the forms of relationships that emerged at the local level as a result of international migration. On the one hand, the twelve–year fighting triggered local, regional and international migration among those whose lives were at risk. Locally, at the level of hometowns such as those described here in detail, there were drastic changes: displaced people from the surrounding rural areas moved towards urban areas. In Nueva Concepción and San Antonio Los Ranchos, this reconfigured the population's structure and presumably undermined the territorial ties of those who migrated to the U.S. later on.

On the other hand, the civil war deepened the political polarization that had begun during the military dictatorships. The stamp of partisan interests on the forms of transnational links was evident in Santa Elena, San Isidro, San Sebastián and Mercedes Umaña. In March 2006, new municipal authorities were elected in El Salvador. An L.A.–based group of migrants created the organization "Al Frente por Santa Elena," which gave financial support to Mayor Nicolás Barrera, who was seeking his third period in the office.14 Furthermore, what used to be cold relations between CASE and the mayor's office turned into a dynamic partnership in 2000, when right–wing party ARENA lost the local elections to the ex–guerrilla candidate. This is reflected in the joint building of a sports area, which Barrera explained to me as follows:

La parte del complejo es un proyecto demasiado grande que lo han ido haciendo poco a poco; entonces, desde antes que yo asumiera la alcaldía ellos ya estaban trabajando; entonces, cuando ganamos la alcaldía nosotros, digamos que las relaciones de ellos ya con el municipio, con la institución, se mejoraron y hemos podido coordinar con el gobierno local; los tomamos muy en cuenta como actores claves y son tomados en cuenta en todas las actividades que la comuna realice.

Most of those who migrated to the U.S. in the 1980s felt politically persecuted, especially the teachers organized in the Asociación Nacional de Educadores–ANDES (Lungo, Eekhof and Baires, 1997). It is therefore important to notice how political preferences might have played a significant role in the formation of transnational ties in Santa Elena. Popkin (1997) and Lungo et al. (1997) describe the HTA, and CASE particularly, as "apolitical". However, I have reached a different conclusion. Based on my interviews, I observed that political and partisan affinities influence the way in which a group of organized migrants relates to the municipality in their community of origin.

In San Isidro, right–wing parties have always prevailed and this political homogeneity has probably contributed to the positive relationship between the local migrant organizations and the mayor's office. Conversely, political differences between the municipal government and the hometown association have discouraged their links in San Sebastián, according to De León and Rodríguez (2004) and Mora (2005), who also observed the same pattern in Mercedes Umaña at the individual level.

Morales and Castillo (2005) framed this political polarization affecting the relationships between migrant and non–migrant populations in terms of "partisan rivalries," which were evident in Santiago Nonualco as well. In other words, political differences and polarization are elements that the authors identify as an obstacle to individual transnational networks in Santiago Nonualco (collective networks have not emerged yet).

In Mercedes Umaña, "los vínculos encontrados no dependen de relaciones con la Alcaldía, sino de vínculos individuales, con una fuerte afinidad por la religión," (Mora, 2005:72). In this municipality and in San Sebastián, Mora identified widespread transnational networks at the individual level, at least on the migrants' side: "[los vínculos] se han institucionalizado en agrupaciones de proyectos comunitarios específicos, pero sin vincularse con el gobierno local". One migrant association from San Sebastián even disappeared because of ideological differences prompted in 2003, when the leftist FMLN lost the municipality to the right–wing party ARENA. The point is that partisan politics is playing an important role in encouraging or discouraging either strong or weak relationships between migrants and local authorities.

The distinct contexts in which people from Santa Elena and San Isidro left their hometowns determined the ways in which they established links with their places of origin. Political persecution prevailed in the former, while in the latter, people were escaping from widespread war violence. Migrant organizations linked to these two places have built stronger ties than some others with their respective hometown municipal authorities, not only because they have had enough time to settle permanently in the U.S., but also because their political preferences are fairly similar and their partisan choices —marked by their past experience during the war— are not that different.

The existence/absence of links between migrants and local communities, and their contributions

Transnational ties at the collective level can be found throughout El Salvador, as attested to by several studies. As seen in Table 2, some hometowns might not have a migrant organization created by former inhabitants but groups of migrants do collect monies to send back home and not exclusively for their families. Migrants may even be asked for contributions through their non–migrant relatives and remittances are sent for community purposes (San Antonio Los Ranchos and Santiago Nonualco). This relationship remains at the level of friends and close or extended family most of the time.

Table 2 also shows that migrant groups have informal contacts with their home communities although not at the institutional level (as seen in San Antonio Los Ranchos with the mayor asking individual migrants to contribute to the local patron saint festivities, for example, but similar interaction can be seen in San Sebastián and Mercedes Umaña). In some other cases, including Nueva Concepción and Santiago Nonualco, there is no evidence of current or past major transnational activities taking place at the level of institutions either formally or informally. The reasons for that might be the weakness of the links between migrants and their local territory. Even in San Antonio Los Ranchos, the link to the local territory is not very strong, because most of those who settled here in the late 1980s after their exile in Honduras were born in other parts of Chalatenango or different departments of the country. Morover, one should consider the fact that their stay in the US has not been that long (as mentioned earlier, they started to emigrate north in the mid–1990s).

The cases I studied show that conflicting political and partisan interests hinder the establishment of strong relations between migrant organizations and mayors. In Santa Elena and San Sebastián, their links shifted completely when the outcome of municipal elections did not bring to office the political parties indirectly supported by groups of organized migrants. On the other hand, there are cases such as Nueva Concepción, where partisan sympathies and affiliations appear to be irrelevant in the explanation of the absence of collective transnational ties in the casco urbano. In cases such as San Antonio Los Ranchos, where hometown associations have not been formed, partisan affinity set the conditions for informal contacts between the mayor and the non–migrant population.

Final remarks

This study aimed to assess refugee political transnationalism in El Salvador. By focusing on the relationships between local governments and migrants in specific territorial communities, I wished to highlight the importance of the study of sub national contexts in the literature of transnationalism. Most of the U.S.–based literature I reviewed centred on more general issues such as the national level (government policies and players) and the migrant component (U.S.–based hometown associations, their origins, contributions and constrains). There is some research on transnationalism in El Salvador and Mexico at the subregional level, but it is concerned with the types of transnational initiatives that have been implemented in these countries and their impact on local development. Within this research, it is also common to find that the analysis of migration policies and recommendations focuses on institutional changes in federal, regional and local entities.

I investigated four cases and relied on research on five additional territorial communities (De León and Rodríguez, 2004; Morales and Castillo, 2005 and Mora, 2005) because I wanted to go beyond the level of analysis mentioned above. I looked at the types of alliances already existing between the mayors' offices, community leaders and former residents of these places, who had settled in the U.S. My study considered just some of the factors that must be taken into account in order to understand why collective transnational activities do not always develop.15

To contribute to this understanding, I analyzed some conditions that I judged relevant. Based on the data, I found that high levels of both international migration and population concentration in areas of settlement in the U.S. are necessary in themselves but certainly not sufficient for the emergence of transnational organizations. These factors might facilitate their creation but although both may have been achieved, transnational networks might remain at the level of individual exchanges.

In addition to the rates of international migration and population concentration in the U.S., I addressed levels and types of political organization during and after the civil war to analyze their impact on migration movements (regional and international) and political relations within Salvadoran municipalities. Paul and Gammage (2004) referred to the issue of pre–existing political ties between Salvadorans without going into detail. I would argue that local politics in conflict and post–conflict situations should be studied more deeply, because this can shed light on the transnational relationships developed at the local level. Salvadoran hometown associations have traditionally been seen as apolitical although this was not entirely true, even in the past. My findings show that partisan sympathies do influence the way in which individual and collective migrants relate to municipal authorities in their places of origin.

The experience of the war and the local dynamics that grew out of it produced political affinities, which affected both non–migrant and migrant populations. Therefore, partisan politics constitute a relevant element to be studied as part of the conditions that may enhance or limit relationships between migrants and local governments in El Salvador.

Most of the literature I reviewed assessed politicization at the partisan level in election periods, showing examples of Mexican or Dominican candidates' tours in the U.S. and their arguable impact on the number of votes. My contention is that politicization should also be studied beyond conjunctural contexts (such as elections) in order to account for the political sympathies that explain the strained or smooth relationships between migrants and local authorities.

As an additional result of the civil war, the structure of the population in several municipalities underwent a lengthy process of reconfiguration. Local, regional and international migration took place, transforming the concept of local belonging among those who had to settle in new places.

There are municipalities where migrants' rights are not fully recognized because they were not born in a specific administrative territory. On the other hand, migrants themselves might not feel completely committed to the development of hometowns where they lived for just a short transition period before leaving for the U.S. To some extent, this situation undermined the migrants' ties to a local Salvadoran territory and, under conditions of relative detachment, transnational activities such as the ones studied here are very unlikely to emerge.

Another consequence of the war is the nature of the organization of collective migrants. Forced migrants of the 1980s, whether they were recognized as refugees or not, were the promoters and founders of many functioning or extinct HTA (Paul and Gammage, 2004). Even today, they are key players in transnational activities taking place in sending and receiving countries. This may say a lot about the special links that developed between forced migrants and their places of origin, probably due to the cruel and violent conditions (economic and political) that forced them to settle elsewhere. Forced migrants of the 1990s, who were not exposed to the risks of the war, may be developing different types of links, which surely warrant further investigation.

The discussion of my findings shows the importance of understanding the aforementioned factors, which help account for variation in both the formation of HTA and, mainly, the type of coordination between municipalities and groups of organized migrants. This analysis suggests that there is a need for more theorization on the effects of variation in hometown communities that were exposed to long periods of civil war, which is the case of most of the municipalities in El Salvador. Most scholars agree that transnationalism should not be conceived of as a uniform process with identical outcomes in different settings. And this paper argues for the need to explore local communities comparing the differences that help one understand the development of transnational ties between migrants and their hometown communities.

I examined how migrants and local governments are interacting and focused on subnational settings, because I consider that their relationships depend on several factors such as those I explored in this paper. These factors may help us analyze whether their formation is contributing to fulfilling the needs of the migrant–sending communities or not. This diagnosis should always be carried out before generalizing the benefits of this kind of interactions.

It is also important to study their actual contributions, because the data I collected show that even the strongest and most successful experiences of collective remittances have a limited impact on the development of peripheral areas within the municipalities. And the same can be said about individual remittances channeled into social or developmental purposes. Moreover, most of these initiatives reach urban populations rather than rural populations, except in rare cases, such as hometown associations created in small villages (cantones or caseríos).

Before prescribing hometown associations and their transnational activities as part of the solution to structural problems in sending countries, one should reflect on the local conditions for either their emergence or their success (in the event that an HTA has been already created). Morales and Castillo (2005) and De León and Rodríguez (2004) argue that relationships between migrant organizations and local communities face several problems such as the limited financial potential of the former and the lack of formal municipal policies directed towards migrants as active players.

My findings point to those elements and others already studied in the literature on transnationalism (Portes and Böröcz, 1989; Guarnizo et al., 1999; Alarcón, 2002) with an emphasis on migrant and non–migrant populations in specific subnational settings. Thus, the analysis should consider their history of migration and organization, levels of political polarization, and partisan affiliation. They should also examine the potential for solidarity and trust, based on indicators such as whether the majority were born within the municipality of last residence.

Bibliography

Al–Ali, Nadje, Richard Black and Khalid Koser, "The Limits of 'Trasnationalism': Bosnian and Eritrean Refugees in Europe as Emerging Transnational Communities", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(4), 2001a, pp. 578–600. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Refugees and Transnationalism: The Experience of Bosnians and Eritreans in Europe", Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(4), 2001b, pp. 615–634. [ Links ]

Andrade Eekhoff, Katharine, and Claudia Marina Silva–Ávalos, "Globalization of the Periphery: The Challenges of Transnational Migration for Local Development in Central America", working document, Flacso, El Salvador, 2003. [ Links ]

Bauböck, Rainer, "Towards a Theory of Political Transnationalism", International Migration Review, 37(3), 2003, pp. 700–723. [ Links ]

Blandón, Flora, "Globalización, migraciones y desarrollo económico local", master's thesis, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (Flacso), Costa Rica, 2002. [ Links ]

De León Villegas, Marvin R., and Gonzalo O. Rodríguez Montano, "Asociaciones de salvadoreños en Los Ángeles, California, USA, y el desarrollo en sus comunidades de origen. Estudio de las Relaciones Transnacionales en San Sebastián, Suchitoto y Tejutla (1992–2004)", master's thesis, Universidad de El Salvador, 2004. [ Links ]

Delgado Wise, Raúl and Héctor Rodríguez R., "The Emergence of Collective Migrants and Their Role in Mexico's Local and Regional Development". Available online at www.migracionydesarrollo.org. 2001. [ Links ]

Fondo de Inversión Social, "Projects Developed Under the Program United in Solidarity until August, 2004". Retrieved September 21, 2005 from http://www.fisdl.gob.sv/Estudios/unidos.htm. 2004. [ Links ]

García, Juan José, "Remesas familiares y relaciones sociales locales: el caso de San Isidro", Flacso (Programa El Salvador), Editorial Universidad Tecnológica, 1996. [ Links ]

García Zamora, Rodolfo, Migración, remesas y desarrollo local, México, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, 2003. [ Links ]

Glick–Schiller, Nina and Georges E. Fouron, "Terrains of Blood and Nation: Haitian Transnational Social Fields", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 1999, pp. 340–366. [ Links ]

Goldring, Luin, "The Mexican State and Transmigrant Organizations: Negotiating the Boundaries of Membership and Participation in the Mexican Nation", Latin American Research Review, 37(3), 2002, pp. 55–99. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Individual and Collective Remittances to Mexico: A Multidimensional Typology of Remittances", Development and Change, 35(4), 2004, pp. 799–840. [ Links ]

González Gutiérrez, Carlos, "Fostering Identities: Mexico's Relations with Its Diaspora", The Journal of American History, 86(2), 1999, pp. 545–567. [ Links ]

Guarnizo, Luis E., "El surgimiento de formaciones transnacionales. Las respuestas de los Estados mexicano y dominicano a la migración transnacional", in Mario Lungo (ed.), Migración internacional y desarrollo, tomo II, El Salvador, Funde, 1997, pp.165–214. [ Links ]

Guarnizo, Luis E., Arturo I. Sánchez and Elizabeth M. Roach, "Mistrust, Fragmented Solidarity, and Transnational Migration: Colombians in New York and Los Angeles", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 1999, pp. 367–396. [ Links ]

Itzigsohn, José, "Immigration and the Boundaries of Citizenship: The Institutions of Immigrants' Political Transnationalism", International Migration Review, 34(4), 2000, pp. 1126–1154. [ Links ]

Landolt, Patricia, "El transnacionalismo político y el derecho al voto en el exterior: el caso de El Salvador y sus migrantes en Estados Unidos", in Leticia Calderón Chelius (ed.), Votar en la distancia: la extensión de derechos políticos a migrantes, experiencias comparadas, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José Ma. Luis Mora, 2003, pp. 301–323. [ Links ]

––––––––––, Lilian Autler and Sonia Baires, "From hermano lejano to hermano mayor: The Dialectics of Salvadoran Transnationalism", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 1999, pp. 290–315. [ Links ]

Levitt, Peggy, "Social Remittances: Migration–Driven, Local–level Forms of Cultural Diffusion", International Migration Review, 32(4), 1998, pp. 926–948. [ Links ]

––––––––––and Rafael de la Dehesa, "Transnational Migration and the Redefinition of the State: Variations and Explanations", International Migration Review, 26(4), 2003, pp. 587–611. [ Links ]

Lungo, Mario, Juan Serarols and Ana Silvia Sintigo, Economía y sostenibilidad en las zonas ex conflictivas en El Salvador, San Salvador, Fundasal, 1997. [ Links ]

Lungo, Mario, Katharine Andrade–Eekhoff and Sonia Baires, "Migración internacional y desarrollo local. El caso de Santa Elena, Usulután, El Salvador", in Mario Lungo (ed.), Migración internacional y desarrollo, volume II, El Salvador, Funde, 1997, pp. 45–87. [ Links ]

Lungo, Mario and Susan Kandel, "Migración internacional, transnacionalismo y cambios socioculturales en Nueva Concepción", Estudios Centroamericanos, 648, October 2002, pp. 911–930. [ Links ]

Mahler, Sarah J., "Theoretical and Empirical Contributions Toward a Research Agenda for Transnationalism", in Michael P. Smith and Luis E. Guarnizo, Transnationalism from Below, New Brunswick (N.J., Transaction Publishers, 1998, pp. 64–100. [ Links ]

Mora, Sandra, "Migración internacional y decisiones públicas locales en El Salvador", master' thesis, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (Flacso), 2005. [ Links ]

Morales, U. and O. Castillo, "Migración, ciudadanía y desarrollo local: una mirada desde el municipio de Santiago Nonualco", master's thesis, Universidad Centroamericana, San Salvador, 2005. [ Links ]

Østergaard–Nielsen, Eva, "The Politics of Migrants' Transnational Political Practices", International Migration Review, 37(3), 2003, pp. 760–786. [ Links ]

Paul, Alison and Sarah Gammage, "Hometown Associations and Development: The Case of El Salvador", Working Paper, Number 3, 2004. [ Links ]

Popkin, Eric, "El papel de las asociaciones de migrantes salvadoreños en Los Ángeles en el desarrollo comunitario", in Mario Lungo (ed.), Migración internacional y desarrollo, volume I, San Salvador, Funde, 1997. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Transnational Migration and Development in Postwar Peripheral States: An Examination of Guatemalan and Salvadoran State Linkages with Their Migrant Populations in Los Angeles", Current Sociology, 51(3/4), 2003, pp. 347–374. [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro, "Conclusion: Towards a New World—The Origins and Effects of Transnational Activities", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 1999, pp. 463–477. [ Links ]

––––––––––and Jòsef Böröcz, "Contemporary Immigration: Theoretical Perspectives on Its Determinants and Modes of Incorporation", International Migration Review, 23(3), 1989, pp. 606–630. [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro, Luis E. Guarnizo and Patricia Landolt, "The Study of Transnationalism: Pitfalls and Promise of an Emergent Research Field", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 1999, pp. 217–237. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, A. "Migración, sociedad y cultura en Nueva Concepción. Una revisión desde la etnografía", in Mario Lungo (ed.), Migración internacional y desarrollo, vol. I, San Salvador, Funde, 1997, pp. 223–269. [ Links ]

Sherman, Rachel, "From State Introversion to State Extension in Mexico: Modes of Emigrant Incorporation, 1900–1997", Theory and Society, vol. 28, núm. 6, December 1999. [ Links ]

Smith, Michael Peter, "Migrant Membership as an Instituted Process: Transnationalization, the State and the Extra–Territorial Conduct of Mexican Politics", International Migration Review, 37(2), 2003, pp. 297–343. [ Links ]

1 This is a short version of an essay I wrote to obtain my Master's degree in Communication and Culture at York University, Toronto. The research was completed in February 2006. I am grateful for the exceptional guidance received from Dr. Luin Goldring, my supervisor at York, as well as the anonymous reviewers of this publication for their suggestions. I assume full responsibility for this document.

2 According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, there were 2 778 286 Salvadorans resident abroad in 2005, accounting for over 20 percent of the total population. The last three governments have implemented various strategies and programs to create and maintain close relationships with Salvadorans living abroad. In 2004, a Vice Minister for Salvadorans Abroad was appointed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

3 For an explanation of this see Glick–Schiller and Fouron, 1999, and Landolt et al., 1999 among others.

4 For studies of conflict and post–conflict situations see, for example, Al–Ali et al. (2001a; 2001b), who focus their research on emerging transnational practices among Eritrean and Bosnian refugees.

5 Asociaciones de Desarrollo Comunal (Community Development Associations), which work closely with municipal authorities but are appointed in general assemblies at the level of the smallest territorial units called cantones. El Salvador is divided in 14 departments, which in turn are partitioned into a total of 262 municipalities (municipios), each of which has several cantones with its respective ADESCO.

6 These are the names of the migrant associations whose acronyms are included in Table 1: Comité Amigos de Santa Elena (CASE), Asociación de San Isidro Cabañas en California (ASINCA) y Amigos de San Isidro Cabaña (ASIC).

7 Interviews conducted: Nicolás Barrera, Mayor of Santa Elena, September 15th, 2005. José Bautista, Mayor of San Isidro, November 15th, 2005. Jorge Benavides, Member of CASE–central in Santa Elena, September 15th, 2005. Sujeiri Flores, Member of ASIC's liaison office in San Isidro, October 10th, 2005. Manuel Landaverde, Main secretary of the municipality of Nueva Concepción, September 9th, 2005. Teresa Martínez, President of the San Antonio Los Ranchos ADESCO, September 9th, 2005. Wilber Mejía, Member of the San Antonio Los Ranchos ADESCO, September 15th, 2005. Filemón Portillo, Member of the Potrero Sula ADESCO in the municipality of Nueva Concepción, November 13th, 2005. José Serrano, Mayor of San Antonio Los Ranchos, September 14th, 2005. Manuel Soriano, Member of the Santa Elena ADESCO, September 15th, 2005.

8 Nevertheless, one of my informants from Potrero Sula assured me that the municipality has worked with a migrant group from this caserío. "Siempre ha habido esa buena sintonía, se han sabido entender. No tienen ningún problema," says Filemón Portillo, member of the Potrero Sula ADESCO. He even mentioned the building of a basketball court, financed jointly by migrants and the mayor's office. The information was not verified by the municipality.

9 For example, the three informants from San Antonio Los Ranchos agreed that people who left for the U.S. have settled in New Jersey, Maryland, Washington D.C. and Los Angeles.

10 Those who were born in San Antonio Los Ranchos probably felt more attached to it than those who were born somewhere else, lived in San Antonio Los Ranchos some years after the war and then left for the U.S.

11 Lungo and Kandel (1999) described this community as having strong lessons in community organization and solidarity, acquired in Mesagrande, Honduras, as refugees. At the end of the 1990s, the authors believed that in San Antonio Los Ranchos the phenomenon of international migration was weak because of the community sociopolitical bonds, but this no longer applies.

12 The local mayor told me that only 5 percent of the population is originally from San Antonio Los Ranchos, the rest were born in eastern Chalatenango and there was a group of ex–guerrilla fighters who settled there after the end of the war.

13 Interviewed on September 14th, 2005.

14 The FMLN candidate (Barrera) lost to the ARENA contender in March, 2006. This research had already finished when this change in the municipal office took place, but it would be an interesting case to follow in future studies.

15 For other factors affecting collective and individual transnational processes see Guarnizo et al. (1999), Itzigsohn, (2000), Delgado and Rodríguez (2001), Orozco (2003), Popkin (2003), Mahler (1998), among others.