Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.3 no.1 Tijuana ene./jun. 2005

Artículos

Mexican Immigrants and Temporary Residents in Canada: Current Knowledge and Future Research

Richard E. Mueller

University of Lethbridge, Dirección electrónica: richard.mueller@uleth.ca

Fecha de recepción: 1 de marzo de 2005.

Fecha de aceptación: 26 de abril de 2005.

Abstract

The migration of Mexicans to Canada is a new phenomenon, but it represents one of the most significant increases in the movement of people from Latin America. Since the mid-1990s, the number of Mexicans in Canada has been growing rapidly because of the return of the descendants of Canadian Mennonites who emigrated to Mexico and the provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which eases the entrance requirements for Mexican nationals. This article looks at the number of Mexicans in Canada, the timeframe of entry, and the number of temporary migrants admitted, and it suggests areas for future research.

Keywords: international migration, Mennonites, NAFTA, Canada, Mexico.

Resumen

La migración de mexicanos a Canadá, aunque es un fenómeno reciente, ha tenido uno de los incrementos más significativos entre los movimientos de personas de América Latina. Desde mediados de los noventa, el número de mexicanos en Canadá ha estado creciendo rápidamente como resultado del retorno de los descendientes de la población menonita que emigró a México y de las disposiciones del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (TLCAN), que facilita el ingreso de ciudadanos mexicanos. En este artículo se examina el número de mexicanos en Canadá, el tiempo de su ingreso y el número de migrantes temporales admitidos, y sugiere áreas de investigación para el futuro.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, menonitas, TLCAN, Canadá, México.

The most Studied human movement in the world may be that of Mexicans entering the United States. Mexican and American academics and policy makers have paid considerable attention to this migration, which has been one of the largest in history. Recently however, Mexican migration to Canada has been quietly increasing. The current number of Mexicans residing in Canada is minuscule compared to their numbers in the United States, which has some 8.5 million Mexican-born residents.1 Nevertheless, between the 1991 and the 2001 Canadian census, the number of Mexicans in Canada increased dramatically, making it the largest group of immigrants from Spanish-speaking Latin America, and among the fastest growing from any country. It remains to be seen if the recent increases in Mexican migration documented here are temporary or constitute a longer-term trend, but certain geopolitical and domestic demographic changes make it likely that flows of Mexican migrants to Canada will continue into the foreseeable future.*

Although the Canadian literature is rich with studies on immigrants, little attention has been paid to Mexican migration, with a couple of notable examples (Whittaker, 1988; Samuel, Gutiérrez, and Vázquez, 1995). One reason is that most studies of Canadian immigration are based on aggregated data or on data disaggregated by immigration cohort or region. Both approaches obfuscate the experience of Mexicans. (For examples, see Baker and Benjamin, 1994; Bloom, Grenier, and Gunderson, 1995;Akbari, 1999; Grant, 1999; Green, 1999; Schaafsma and Sweetman, 2001; Frenette and Morissette, 2003; and the empirical work contained in Beach, Green, and Reitz, 2003.) Given the recent increase of Mexican immigration to Canada, the lack of information on the group represents a serious gap in our knowledge.

The importance of Studying Mexicans in Canada is underlined by the likelihood that their numbers will continue to increase over the foreseeable future. This will be owing to advanced economic integration resulting from the full implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), demographic shifts in the Canadian population that will increase the need to import low-skilled labor, the arrival of increasing numbers of Mexican temporary workers and students, and even the continuing return of the Mennonite population from Northern Mexico.

Using the existing literature, this article identifies the state of knowledge about the Mexican-born living in Canada. To provide a profile and quantification of Mexicans residing both permanently and on a temporary basis in Canada, the article uses data from the 2001 Canadian census and recent data from Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC).2 The probable labor-market performance of Mexicans in Canada is also examined. Because we should not view Mexican migration to Canada in isolation, where possible, the article compares this group to other immigrant groups, including those from Latin America.3 Finally the article also considers areas for future research that would help not only to close the knowledge gap but to enhance our understanding of this increasingly important immigrant group.

Recent Mexican Migrant Flows

To address the shortcomings in knowledge about Mexican immigration to Canada, the first task at hand is to quantify the extent of that migration. CIC disaggregates migrants to Canada into "permanent" and "temporary" residents. The members of the former group have permanent residence status and can ultimately apply to become Canadian citizens. The latter group includes visitors, workers, and students, all of whom are expected to return to their countries of origin.

In Canada, the number of permanent and temporary residents from Mexico almost doubled from 1991 to 2001, rising from 22,035 to 42,720. This was the largest numerical increase for any group from Latin America over that period (see Table 1). Even in percentage terms, this increase was dramatic; only Colombia, Venezuela, Cuba, and Guadeloupe had larger percentage changes in that period. By 2001, Mexico had a higher percentage of its nationals living in Canada than did any other country in the region, except for Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Permanent Residents

The composition and timing of Mexican migration flows is interesting. About one-half of the 36,225 permanent Mexican immigrants in Canada reported in the 2001 census had arrived between 1991 and 2001 compared to about one-third of immigrants from all Other Latin American countries, a figure similar to Other immigrant groups (see Table 2). In each successive ten-year period, the Mexican cohort has about doubled in size, from 2,140 entries in 1961-1970, to 18,115 in 1991-200Thus, Mexican immigration is much more recent than that from Other areas. Why has there been a sudden surge in Mexican immigration to Canada?

At first glance, the numbers seem to support the hypothesis that the NAFTA has facilitated the flow of Mexicans to Canada. According to Philip Martin (2004), as reorganization of the Mexican economy following the implementation of NAFTA displaced workers, increased migration to the United States was expected. A reduction in those flows was also expected after the restructuring of the Mexican economy and the commensurate job creation. Certainly those factors could be responsible for some of the increase in Canada, as well. The provisions of the NAFTA made it easier for Mexicans to enter Canada to work and do business.4 These NAFTA work permits are not immigrant visas and do not directly lead to permanent-resident status or Canadian citizenship, but they can lead to the increased flow of information from Canada to Mexico, which in turn can facilitate both temporary and permanent immigration by others.

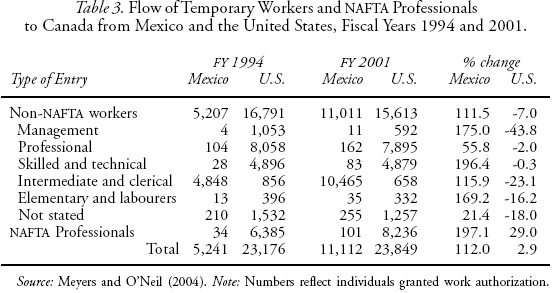

The number of Mexican workers granted authorization to work in Canada increased by 112% between 1994 (the year that NAFTA came into effect) and 2001 (Table 3). This figure exceeds the growth in the number of work authorizations granted to American workers over the same period (Table 4).5 This growth in Mexican temporary workers has been across all entry types, but the largest numerical increase was in the intermediate and clerical categories, where almost all of the workers are employed in agriculture as a result of the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SAWP). This does not mean that NAFTA has not had an impact on the flow of Mexican workers to Canada, only that the direct effect of NAFTA has been minimal in terms of Mexican workers arriving in Canada. By way of comparison, Mexicans and Canadians are entering the United States on a temporary basis in much larger numbers, in terms of both absolute numbers of entries as well as the percentage growth rates in the post-NAFTA period.

Another possible explanation for the sudden increase is that returning Mennonites have increased the Mexican-born population in Canada. Between 6,000 and 7,000 Mennonites emigrated from the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan to the states of Chihuahua and Durango in the 1920s, following attempts to impose mandatory English-language school attendance on Mennonite children and because of pressure from neighbors who responded negatively to the Mennonites' military exemption following the Conscriptíon Act of 1917. Mexico promised them a continued military exemption as well as the right to operate their own schools in their own language. Although Mennonites have been moving between Canada and Mexico since the 1920s, the pace of return migration to Canada quickened during the last two decades of the twentieth century. This has been attributed to increased globalization (in general) and the NAPTA (in particular), as agricultural prices in Mexico have decreased while the cost of living has increased. Land is also scarce and there are Other non-economic factors, such as increased drug and alcohol use among the group's young people.6 Estimates suggest that at least 40,000 Latin American-born Mennonites and their descendents now live in Canada, many having returned from Mexico during the 1980s and 1990s. Since these individuals were born to parents of Canadian ancestry those that the Canadian government considered to be citizens could bypass the normal Canadian immigration procedure. (Janzen 2004 explains how the Mennonites from Latin American countries were "repatriated" to Canada.)

The number of Mexicans entering Canada permanently has increased by 127%, from 786 in 1994 to T783 in 2003 (Table 5).7 Assuming that the immigration of the Mexican-born was comprised entirely of those who had to follow the normal immigration channels, the numbers in Table 5 should exceed those in Table 2, owing to return migration, migration to a third country, and deaths while in Canada. However, the numbers in Table 5 are smaller than the annual averages that can be calculated from Table 2, which suggests that the return to Canada of the Mennonite population has been sizeable since these individuals will show up in the census data but not in the immigration numbers.

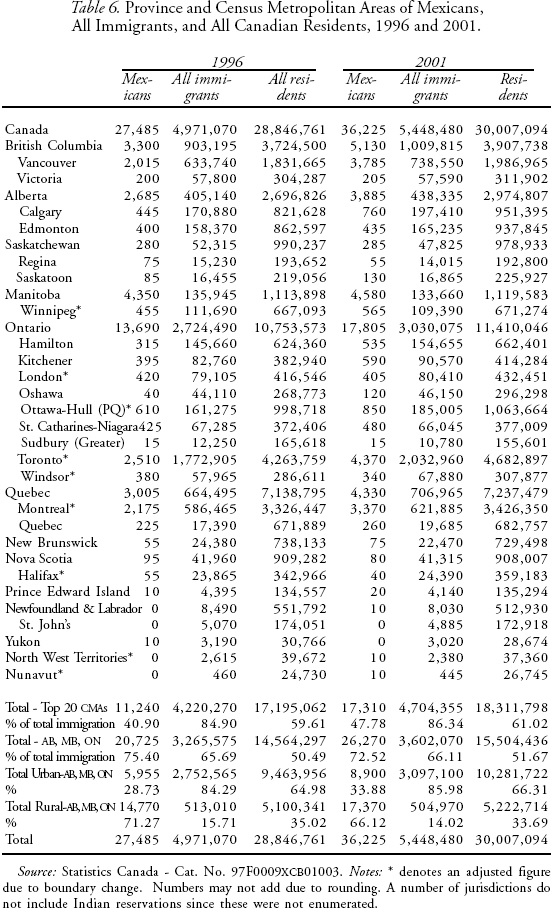

As further proof of the importance of this return migration, the Mennonite population in Canada is concentrated mainly in Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta, primarily in those provinces' rural areas. Comparing the provinces and cities of where Mexican-born residents reside with those where the Canadian-born and immigrants from Other groups reside may be useful in determining the nature of the Mexican migration. Immigrants to Canada tend to Iive in the largest Canadian cities. Indeed, in 1996, almost 85% of all immigrants lived in one of Canada's 20 largest cities, and in 2001, the figure was nearly the same, 86%. Both figures are about 25 percent age points higher than the same figures for all Canadian residents (both immigrants and natives). As of 2001, only 48% of the Mexican population lives in the 20 largest cities, however.

Another interesting comparison is that just over half of all Canadian residents lived in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario in 2001, whereas over 70% of the Mexican-born lived there and only about 30% lived in the three provinces' 12 urban areas. Those figures are consistent with a large migration of Mennonites from Mexico. Together with the evidence presented above, this suggests that a sizeabíe number bypassed the usual immigration channels.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation allows us to estimate the numbers of Mennonites and non-Mennonite Mexican-born individuals living in Canada in 1996 and 2001 (see Table 6). Assuming that Mexicans of non-Mennonite background would be distributed throughout Canada in the same proportions as immigrants from all Other source countries, we can estimate the number of Mennonites and non-Mennonites who entered from Mexico: In 1996, 11,934 of the 27,485 Mexican-born residing in Canada were Mennonites and 15,551 were not. In 2001, approximately 14,012 were returning Mennonites compared to 22,213 Mexican-born non-Mennonites.8 This represents increases of 17.4% and a 42.8%, respectively among the Mennonite and non-Mennonite population of Mexican-born individuals in Canada.

In sum, the increase in Mexican migration to Canada appears to be due to both the sizable flows of Mennonites of Canadian descent returning to Canada as well as a general increase in the number of Mexican-born residents in Canada. According to this rough estimate, in recent years, the group of Mexican-born non-Mennonites in Canada is larger and has been growing faster than has the Mexican-born Mennonite population. The increase in the number of temporary workers due to NAFTA may possibly also explain a portion of this flow, although the direct effects of NAFTA are small, as will be seen next.

Temporary Residents

Canadian temporary-migration permits are available in four main categories: (1) student, (2) temporary worker, (3) humanitarian (refugee) arrival, and (4) "other." Temporary migrants can hold more than one permit (Zlotnik, 1996:86). Although the "other" group is sizeable— some 72,024 of the total 244,922 admittances in 2003, primarily visitors—there is scant information on the group (CIC, 2005). Below, we will discuss the first three categories.

Students

The flow of Mexican students to Canada is high, but the Stock of Mexican students is not (CIC 2003). This indicates that many Mexicans come to Canada to Study for a short period (Table 7).9 In 2001, 4,847 Mexican students came to Study in Canada (almost 7% of all foreign students) while stocks (4,475 Mexican students) accounted for only 3% of Canada's foreign students. Akhough these stocks are small, they have increased fivefold since 1990 when there were only 882 Mexican students in Canada. This increase is likely due to the NAFTA, expedited medical procedures for foreign students, the appreciation of the Mexican peso since 1997, and the establishment of three Canadian Education Centres (CECs) in Mexico, which promote Canadian educational institutions (CIC 2003). Between 1990 and 2001, the number of Mexican students in Canada increased 400%, compared to only about 56% between 1980 and 1990. In the latter instance, the increase was consistent with the increase in the numbers of students from all countries, but the increase from 1990 to 2001 is about three times greater for Mexican students compared to students from all countries. The increase has come as the result of higher enrollments in all types of training courses, but predominantly in trades, universities, and Other post-secondary institutions (colleges and technical institutes).

This sharp increase has important implications for permanent immigration to Canada since foreign students often seek permanent residency upon the completion of their studies, adding an important source of talent to the Canadian labor market. As immigration minister Joe Volpe told the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration:

International students also represent a current and future pool of talent for many businesses right across Canada. That's why my Department is currently looking at ways to make sure Canada can attract more foreign students to come and study at Canadian universities and colleges and to better integrate into the labor market those who wish to gain Canadian work experience.

Training foreign students in Canada also overcomes the problem of foreign credential recognition that so often plagues immigrants with foreign education and experience.

Temporary Workers

Mexico is second only to the United States in the number of foreign workers who entered Canada annually from 1994 through 2003 (Table 8). In each of those years, Mexicans form the second or third largest stock of foreign temporary workers (Table 9). The fact that Mexico places second in the flow of workers, but third in the stock of foreign workers is likely due to the fact that these flows of immigrants are quite different. The Mexican migration is comprised of males working under the auspices of the SAWP. The program initially bought farm workers from the Caribbean to reduce seasonal domestic-labor shortages on Canadian fruit and vegetable farms, which had been experienced since the Second World War. In 1974, Mexican workers were allowed to join the program. (See Basok 2000, 2002, 2003 for a review of the program details as well as its outcomes in terms of living Standards, treatment of workers, and investment in Mexico by these workers with money earned in Canada.) In 2004, this program brought 18,755 farm workers to Canada; about 10,000 of whom were Mexicans. Most work 10- to 12hour days, six days a week for four to eight months. The job market for nannies and domestics in Canadian households, by contrast, is dominated by temporary workers from the Philippines. Most Mexican farm workers have returned home by December 1, when the stock of foreign workers is enumerated.

Whereas there is little information on most Mexican immigrants in Canada, recently, the SAWP has been Studied extensively. Both Canadian and Mexican government officials have hailed the program as a success, often pointing to the return rate to Canada of Mexicans (who can be requested by name by Canadian employers). For example, Carlos Obrador, Mexicos vice-consul in Toronto, said that the Mexico-Canada guest worker program "is a real model for how migration can work in an ordered and legal way." According to the Mexican government, 80% of Mexican workers are repeat hires and very few Stay on in Canada illegally. Then-Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, in Mexico in March 2003, said:

This program where your farmers can come and work in Canada has worked extremely well and now we are exploring (ways) to extend that to Other sectors. The bilateral seasonal agricultural workers program has been a model for balancing the flow of temporary foreign workers with the needs of Canadian employers.

Still, there have been problems, most of which have arisen from the bureaucracy on the Mexican end of the program, as well as the expense and time off requent travel to Mexico City to obtain the required documents. There have also been some complaints that workers are not treated well yet are afraid to criticize substandard working conditions for fear of not being able to return the following year. Still, the high-return rate suggests that the SAWPs beneficial aspects outweigh the problems, at least as far as the workers themselves are concerned.

Although the number of farm-related workers arriving in Canada in the 1990s has increased dramatically, there has been only a modest increase in the number of Other Mexicans coming to Canada to work on a temporary basis (Table 3). The number of temporary workers coming to Canada from Mexico increased by 112% between 1994 and 2001, but most of this growth has come as a result of the increase in farm workers (intermediate and clerical workers). The numbers of workers admitted under many Other categories (including those entering under the provisions of NAFTA) have increased more dramatically in percentage terms, although they are still small in absolute numbers.10

Still, one might have expected the number of NAFTA workers to have increased in Canada over this period, owing to the heightened restrictions placed on temporary Mexican workers entering the United States I even under the provisions of NAFTA (Papademetriou, 2003). Canadian "Ψ professionals have a much easier time crossing the border into the United States than do their Mexican counterparts. The Canadians only need to document their professional credentials and have an offer letter from a U.S. employer in order to obtain a TN (or NAFTA professional) visa. The application can be processed at any port-of-entry along the U.S.-Canadian border. By contrast, Mexican professionals must have a visa from a U.S. consulate, documentation of credentials, and an offer letter from a U.S. employer. In addition, the prospective employer must file a labor-conditions application. Furthermore, until 2004, no more than 5,000 TN visas that could be issued to Mexican nationals annually (although that limit may was not binding. While a TN visa allows individuals to work in the country for one year at a time (with an unlimited number of extensions), an H-1B visa allows for three years of work (renewable once to a maximum of six years). For Mexican professionals, both the TN and H-1B visas require similar paperwork, yet for Canadians, it is much more time consuming and costly to apply for an H-1B visa than a TN visa (Jachimowicz and Meyers, 2002). For Mexicans, the opposite is true and evidence suggests that Mexican professionals have been following the traditional routes of temporary migration and applying for these visas which offer better security with about the same amount of paperwork (Papademetriou, 2003).

Humanitarian Arrivals

In 2003, Mexico ranked third on the list of humanitarian arrivals in Canada, with 2,428 individual cases, a figure about ten times higher than the same figures in 1994 (Table 10).11 Over that nine-year period, Mexico ranked third in terms of growth rate (behind only Colombia and Costa Rica). Although current published sources do not disaggregate the reasons given by asylum seekers, we do know that the number of Mexicans seeking entry into Canada has increased.

Sebastián Escalante (2004) showed that sexual orientation and domestic violence were the two most common reasons given by Mexican refugee claimants in Canada in 1996 and 1997. In 1996, Mexicans presented 951 claims to the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB), and in 1997, 926 (Mexico ranked ninth and sixth, respectively in terms of the percentage of total claims). Most were either rejected, finalized by Other means, or became part of the backlog of refugee claimants. Escalante argues that the widespread assumption that Mexicans refugee claimants are simply economic migrants or tourists is not true. However, he does not present evidence showing the positive determinations of Mexican cases versus Other refugee claimants, so we do not know the success rate (and therefore, presumably the legitimacy) of these claims in comparison to Other source countries. In 2004, the IRB finalized 2,684 claims by Mexicans. Only 25% were accepted, compared to an overall acceptance rate of 40%.12

Canadian Labor-Market Performance

Canada accepts the majority of its immigrants based on their ability to perform well in the labor market and to contribute to Canadian society For Canadian economists and policy makers, the most important question is how immigrants perform in the labor market, both in absolute I terms, and relative to Other immigrant groups and native-born Canadians. For Mexican immigrants and temporary residents in Canada, however, there is almost no information about their labor-market assimilation . In Other words, how well do Mexican immigrants adapt to the Canadian labor market? This dearth of information is largely owing to the inclusion of Mexicans within the aggregated group of "all Latin Americans" (for example, in the Canadian Census Public Use Microdata Files). What information exists is only of limited use for commenting on the successful labor-market assimilation of Mexicans in Canada.

David A. Green (1999) has shown that more recent cohorts are less skilled than were previous cohorts, and those immigrants who are not assessed on their skills or are not fluent in English at the time of arrival are less occupationally mobile. Although we currently have no idea about the number of Mexicans entering as economic immigrants (that is, those assessed by CIC on their labor-market skills), the increasing number of humanitarian arrivals from Mexico does not bode well for their potential success in the Canadian labor market. Elizabeth McIssac (2003) also shows that in the 1990s, newer immigrants in general had lower employment rates, higher unemployment rates, and lower wages, relative to both earlier immigrants and native-born Canadians, even though these recent immigrants have higher educational levels then the Other two groups. She argues that this is due to problems with Canadians accepting or recognizing foreign credentials. Marc Frenette and René Morissette (2003) compared data from 2001 Census to earlier censuses and found that the most recent immigrants have lower wages, and prime-aged immigrant workers (those in the middle of their working lives) are mainly affected, which further suggests that foreign labor-market experience is not valued in Canada. A Statistics Canada (2003) survey showed that six of 10 recent immigrants to Canada worked in different occupations than the ones they had had before coming to Canada, and that many immigrants were concentrated in relatively low-skilled occupations, such as manufacturing and sales. Jeffrey Reitz (2005: 3) summarizes this nicely:

Although education credentials among recent immigrants have been higher on average than those of Canadas native-born workforce and are rising, and despite the fact that recent immigrants' levels of fluency in one official language have not changed, the trends in immigrants' employment and earnings are downward. This suggests that the real problem is not so much their skill levels, important as they may be, but rather the extent to which these skills are accepted and effectively Utilized in the Canadian workplace.

Thus, the Canadian labor market may be under-utilizing immigrants' skills, and this is reflected in their incomes. Bente Bakhd (2004) conducted interviews with survey groups of immigrants and found that many who obtained Canadian education credentials or experience in Canada felt that this was essential to their labor market success. Similarly, Arthur Sweetman (2004) has shown that earnings for immigrants educated in their home countries is positively correlated with the general quality of education in those countries as measured by mean Standardized international test scores. Unfortunately Mexico does not rank well compared to Other countries in these tests, implying that Mexicans who were educated in Mexico may be at a significant earnings disadvantage in Canada (the good news is that immigrants educated m Canada do not generally have this problem). Similarly Naomi Alboim and her co-authors (2005) show that Canadian education increases the return to foreign education, but Canadian experience does not increase the return to foreign experience. Since the majority of Mexicans entered Canada during the 1990s, this recent decline in immigrant wages may disproportionately affect this group. Furthermore, the chances of emigrating from Canada appear to be higher for immigrants who have had difficulty finding good employment in the Canadian labor market because of, among Other things, credential recognition These authors find that 4.3% of all permanent immigrants who landed in Canada in the 1990s had emigrated from Canada by 2000, based on an analysis of income tax returns. For those from South and Central America, this figure is only 2.6%, one of the lowest proportions for any source region (Dryburgh and Hamel, 2004:15).

Related to labor-market performance is the incidence of poverty among immigrant groups, both in absolute and relative terms. Immigrants are over-represented at both the high and the low end of the earnings distribution (Kazemipur and Halli, 2000:81). In 1991, the Canadian national poverty rate was 15-6%; Latin Americans had the highest poverty rate (41%) of any ethnic group (2000:83). These high levels of poverty might be due to the recent nature of migration from Latin America. Notably Canada experienced a recession in 1991, which probably inflated the poverty rates for those newcomers as they had yet to fully integrated into the Canadian labor market. Moreover, the age-earnings profile of Canadian males, both high school and university graduates, deteriorated during the last quarter of the twentieth century, which might also affect labor-market assimilation (Beaudry and Green, 2000).

Mexico has allowed dual citizenship since 1996, and so one small positive development for assimilation is the number of Mexicans acquiring Canadian citizenship. Because Mexican migratory flows are fairly new and there is a long waiting period to acquire citizenship, the number of Mexicans granted Canadian citizenship is still not high: In 2000, only 1,286 individuals naturalized (Migration Policy Institute, no date). Still this represents an increase of 128% since 1996 and, given the propensity of immigrants with higher-than-average human-capital endowments to self-select into citizenship, this is a particular positive development for Canada (DeVoretz and Pivnenko, 2004).

Without the benefit of disaggregated data and a solid multivariate analysis, we can only speculate about the labor-market performance of Mexicans living in Canada vis-à-vis Other immigrants groups and native-born Canadians.

Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

Mexicans, arriving in greater numbers as immigrants, temporary workers, students, and even refugees, have become increasingly important in Canada. Still, little is known about this group, aside from the fact that there are more Mexicans in Canada today than ever before, and that this group has been growing at a rapid rate. This demographic change is likely the result of both the returning Mennonite population and the provisions of the NAFTA, which make entry into Canada less burdensome for Mexican nationals. The recent literature on immigration to Canada indicates that it will be difficult for these groups to succeed economically in the Canadian labor market. Unfortunately much of what we can infer from this published research is speculative in regard to Mexicans since most of this research does not disaggregate immigrants by country of origin. As such, it is almost impossible to determine how Mexicans are doing economically in Canada, especially given the diversity of the Mexican immigrant population, which ranges from highly skilled professionals to low-skilled workers.

It is expected that the recent increase in Mexicans coming into Canada will continue for several reasons. Economic integration will deepen as the NAFTA provisions fully take effect. As the ranks of Mexican immigrants swell, migrant networks will form and consolidate, providing a demonstration effect and facilitating the flow of information back to Mexico about Canada as an alternative destination to the United States. Canada is facing demographic changes, including a skills shortage and the retirement of the baby boomers (Baklid, 2004). The shortage will particularly occur among low-skilled workers, which could put pressure on policymakers to expand programs such as the SAWP into areas beyond agriculture (Burstein and Biles, 2003).

Although the number of Mexicans desiring to migrate is expected to decrease m the longer term, as birth rates in Mexico fall and the Mexican economy improves and offers better employment opportunities to its citizens (Martin, 2004), over the near term, the potential for migration growth to Canada continues. This underscores the main point of this article: Little is known about this increasingly important group of migrants and this gap in our collective knowledge that should be closed. Directions for future research include:

• What are the characteristics of the Mexicans who immigrate to Canada? How does this group compare to Other immigrants in terms of the main indicators for labor-market performance: age at arrival, education, language ability (in English or French), labor-market experience, and so forth?

• How have recent Mexican immigrants performed in the labor market compared to Other immigrants? Is credential recognition, as well as Other barriers to the Canadian labor market, a problem for Mexicans as it is for immigrants in general?

• Why are more Mexican students Studying in Canada? What is their likelihood of remaining in the country following graduation?

• On what type of abuse or persecution do Mexicans base their claims for refugee status? Why is the proportion of successful refugee claims so low for Mexico compared to the success rates from Other source countries?

Some of the data necessary to answer these questions do exist, but as noted above, they generally have not been exploited by researchers: CIC provides special tabulations to researchers, and every five years, Statistics Canada releases census microdata with detailed information on the foreign-born population in Canada. Statistics Canada also manages the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB), which combines the landing data on immigrants to their taxation records,13 and the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC) contains similar data. Statistics Canada conducts numerous Other surveys that may be useful as well.14 Finally the Immigration and Refugee Board and Other sources provide detailed information on many refugee cases.

The rapid increase in the number of Mexicans residing both permanently and temporarily in Canada is likely to increase over the next few years. Despite the relative importance of one of Canada's newest groups of immigrants, we understand very little about these migrants and how they are assimilating into the Canadian labor market. It is hoped that this article will inspire more research regarding this large and disparate group of immigrants to Canada.

References

Abbott, Michael G., "The IMDB: A User's Overview of the Immigration Database", in Charles M. Beach, Alan G. Green, and Jeffrey CL Reitz (eds.), Canadian Immigration Policy for the 21" Century, Kingston, Queerís University, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy in cooperation with McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003, pp. 315-322. [ Links ]

Akbari, Ather H., "Immigrant 'Quality' in Canada: More Direct Evidence of Human Capital Content, 1956-1994", International Migration Review, vol. 33, no. 1, Spring 1999, pp. 156-175. [ Links ]

Alboim, Naomi, Ross Finnie, and Ronald Meng, "The Discounting of Immigrants' Skills in Canada: Evidence and Policy Recommendation", Choices, vol. 11, no. 2, Institute for Research on Public Policy, February 2005. [ Links ]

Baker, Michael, and Dwayne Benjamin, "The Performance of Immigrants in the Canadian Labor Market", Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 12, no. 3, July 1994, pp 369-405. [ Links ]

Baklid, Bente, "The Voices of Visible Minorities: Speaking Out on Breaking Down Barriers", Conference Board of Canada Briefing, September 2004. [ Links ]

Basok, Tanya, "Migration of Mexican Seasonal Farm Workers to Canada and Development: Obstacles to Productive Investment", International Migration Review, vol. 34, no. 1, Spring 2000, pp. 79-97. [ Links ]

----------, Tortillas and Tomatoes: Transmigrant Mexican Harvesters, Montreal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2002. [ Links ]

----------, "Mexican Seasonal Migration to Canada and Development: A Community-based Comparison", International Migration, vol. 41, no. 2, July 2003, pp. 3-26. [ Links ]

Beach, Charles M., Alan G. Green, and Jeffrey G. Reitz (eds.), Canadian Immigration Policy for the2T' Century, Kingston, Queen's University, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Econornic Policy in Cooperation with McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Beaudry Paul, and David A. Green, "Cohort Patterns in Canadian Earnings: Assessing the Role of Skill Premia in Inequality Trends", Canadian Journal of Economics, vol. 33, no. 4, November 2000, pp. 907-936. [ Links ]

Bloom, David E., Gilles Grenier, and Morley Gunderson, "The Changing Labor Market Position of Canadian Immigrants", Canadian Journal of Economics, vol. 28, no. 4b, November 1995, pp. 987-1005. [ Links ]

Burstein, Meyer, and John Biles, "Immigration: Economics and More", Canadian Issues, April 2003. [ Links ]

"Canada: Guest Workers", in Migration News, vol. 9, no. 3, University of California, Davis, March 1, 2002. Available at migration.ucdavis.edu/mn/more.php?id=2576_0_2_0. [ Links ]

"Canada", in Rural Migration News, vol. 10, no. 4, University of California, Davis, September 28, 2002. Available at migration.ucdavis.edu/rmn/more.php?id=918_0_4_0. [ Links ]

Castro, Pedro, "The 'Return' of the Mennonites from the Cuauhtémoc Region to Canada: A Perspective from Mexico", Journal of Mennonite Studies, vol. 22, 2004, pp. 25-38. [ Links ]

Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), "Foreign Students in Canada", in Priorities, Planning and Research Branch, Ottawa, CIC, 2003. [ Links ]

----------, Facts and Figures 2003-Immigration Overview: Permanentand Temporary Residents, Ottawa, Minister of Public Works, 2005. [ Links ]

DeVoretz, Don J., and Sergiy Pivnenko, "The Economic Causes and Consequences of Canadian Citizenship", IZA Discussion Paper, no. 1395, Bonn, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (Institute for the Study of Labor), 2004. Available on the "Publications" page at www.iza.org. [ Links ]

Dryburgh, Heather, and Jason Hamel, "Immigrants in Demand: Staying or Leaving?", Canadian Social Trends, Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 11-008, Autumn 2004, pp. 12-17. [ Links ]

Escalante, Sebastián, "Disrupting Mexican Refugee Constructs: Women, Gays, and Lesbians in 1990s Canada", in Barbara J. Messamore (ed.), Canadian Migration Patterns from Britain and North America, Ottawa, University of Ottawa Press, 2004, pp. 207-228. [ Links ]

Frenette, Marc, and René Morissette, Will They Ever Converge? Earnings of Immigrant and Canadian-born Workers over the Last Two Decades", Statistics Canada Analytic Studies Research Paper Series, no. 215, 2003. [ Links ]

Grant, Mary L., "Evidence of New Immigrant Assimilation in Canada", Canadian Joumal of Economics, vol. 32, no. 4, August 1999, pp. 930-955. [ Links ]

Green, David A., "Immigrant Occupation Attainment: Assimilation and Mobility over Time, Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 17, no. 1, January 1999, pp. 49-79. [ Links ]

Jachimowicz, Maia, and Deborah W. Meyers, "Temporary High-Skilled Migration", Migration Policy Institute, November 2002. Available at http://www.migrationinformation.org/USfocus/display.cfm?ID=69. [ Links ]

Janzen, William, "Welcoming the Returning 'Kanadier' Mennonites from Mexico", Journal of Mennonite Studies, vol. 22, 2004, pp. 11-24. [ Links ]

Justus, Martha, and Jessie-Lynn MacDonald, "Longitudinal Surveys of Immigrants to Canada", in Charles M. Beach, Alan G. Green, and Jeffrey G. Reitz (eds.), Canadian Immigration Policy for the 21" Century, Kingston, Queen's University, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy in cooperation with McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003, pp. 323-326. [ Links ]

Kazemipur, Abdolmohammad, and Shiva S. Halli, "The Colour of Poverty: A Study of the Poverty of Ethnic and Immigrant Groups in Canada", International Migration, vol. 38, no. 1, 2000, pp. 69-88. [ Links ]

Martin, Philip, "New NAFTA and Mexico-U.S. Migration: The 2004 Policy Options", Update, Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics/University of California at Davis, vol. 8, no. 2, November-December 2004. [ Links ]

McIssac, Elizabeth, "Immigrants in Canadian Cities: Census 2001-What do the Data Tell Us?, Policy options, vol. 24, no. 5, May 2003, pp. 58-63. [ Links ]

Meyers, Deborah W., and Kevin O'Neil, "Immigration - Mapping the New North American Reality", Policy options, vol. 25, no. 6, June-July 2004, pp. 4-8. [ Links ]

Migration Policy Institute, "Country: Canada", Global Data Center. Available at http://www.migrationinformation.org/GlobalData/countrydata/country.cfm (select "Canada" from the drop-down menu). [ Links ]

Norris, Doug, "New Household Survey on Immigration", in Charles M. Beach, Alan G. Green, and Jeffrey G. Reitz (eds.), Canadian Immigration Policy for the 21st Century, Kingston, Queen's University, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy in cooperation with McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003, pp. 327-332. [ Links ]

Papademetriou, Demetrios G., "The Shifting Expectations of Free Trade and Migration", in NAFTAs Promise and Reality: Lessons from Mexico for the Hemisphere, Washington, D.C., Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2003. [ Links ]

Reitz, Jeffrey G., "Tapping Immigrants' Skills: New Direction for Canadian Immigration Policy in the Knowledge Economy", Choices, vol. 11, no. 1, Institute for Research on Public Policy, February 2005. [ Links ]

Samuel, T John, Rodolfo Gutiérrez, and Gabriela Vázquez, "International Migration between Canada and Mexico: Retrospect and Prospects", Canadian Studies in Population, vol. 22, no. 1, 1995, pp. 49-65. [ Links ]

Schaafsma, Joseph, and Arthur Sweetman, "Immigrant Earnings: Age at Immigration Matters", Canadian Journal of Economics, vol. 34, no. 4, November 2001, pp. 1066-1099. [ Links ]

Statistics Canada, Long Itudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, Ottawa, Statistics Canada, 2003. [ Links ]

Sweetman, Arthur, "Immigrant Source Country Educational Quality and Canadian Labor Market Outcomes", Statistics Canada Analytical Studies Research Paper Series, No. 234, 2004. [ Links ]

Volpe, Joe, "Notes for an Address by the Honourable Joe Volpe", Minister of Citizenship and Immigration before a meeting of the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration Ottawa, Ontario, February 24, 2005. Available at http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/press/speech-volpe/budget2005-html. [ Links ]

Whittaker, Elvi, "The Mexican Presence in Canada: Liberality Uncertainty and Nostalgia", Journal of Ethnic Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, Summer 1988 pp. 29-46. [ Links ]

Young, Linda Wilcox, "Free Trade or Fair Trade?: NAFTA and Agricultural Labor", Latin American Perspectives, vol. 22, no. 1, Winter 1995, pp. 49-58. [ Links ]

Zlotnik, Hania, "Policies and Migration Trends in the North American System", in Alan B. Simmons (ed.), International Migration, Refugee Flows and Human Rights in North America: The Impact of Free Trade and Restructuring, New York, Center for Migration Studies, 1996, pp. 81-103. [ Links ]

1 These figures, based on U.S. Census data, are from "Indicadores seleccionados de la población nacida en México residente en Estados Unidos de América, 1970-2000," Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI), available at http://www.inegi.gob.mx/est/contenidos/espanol/rutinas/ept.aspit=mpob65&c=3242.

* An earlier version of this article was presented in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico, on March 4, 2005, at the XI Conferencia de la Asociación Mexicana de Estudios sobre Canadá. I would like to thank the many conference participants for a helpful discussion as well as the two anonymous referees for their useful comments.

2 CIC is the federal government agency responsible for regulating immigration to Canada. It is akin to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) in the United States, formerly called the Immigration and Naturalization Service (lNS).

3 In this article, "Latin America" refers to all countries all countries south of the United States, including Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean.

4 There are four categories of NAFTA workers. Business visitors are involved in international commercial activities and need to visit Canada to Fulfill their duties. These individuals do not enter the Canadian labor market and they receive their compensation from outside of Canada. Intra-company transferees are Mexican or American citizens who, under certain conditions, can enter Canada with a work permit issued at the point of entry. Investors and traders are those individuals who intend to invest substantially in Canadian businesses, or who are involved in significant trade with Canada. These individuals are required to have work permits, which are usually issued outside of Canada. Professionals are those with advanced education, who work in certain occupations, and who have pre-arranged employment in Canada. They are compensated in Canada, and they enter with a work permit.

5 Of course, the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement was implemented in 1989 and the U.S. economy performed extremely well in the 1990s, both of which may explain the paltry growth in work authorizations for Canada over this period. Still, it should be noted that the issuance of NAFTA professional visas increased while all other work authorization categories declined.

6 See Linda Wilcox Young (1995) for a discussion of some of the expected displacements to agricultural labor in the post-NAFTA period, most of which have been borne out with time. See also the Mennonite Central Committee website (www.mcc.org) for a brief background about the migration of Mennonites throughout the world, and Pedro Castro (2004) for detailed discussion of these returning Mennonites.

7 The percentage increases of Colombians, Cubans, and Argentines to Canada over this same per10d are larger. The first two cases are likely the result of increased refugee flows, and the latter, the result of the economic crisis in Argentina.

8 These numbers are calculated by assuming that the proportion of non-Mennonite Mexican who immigrated to Canada and were distributed throughout the country in the same proportions of those who emigrated from all source countries. If we assume that all Mexicans in Canada in 1996 had the same settlement patterns as the group of all immigrants, then 65-59% of the Mexican born would live in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, and 15.71% of these individuals would live in rural areas. In other words, 2,836 of the 27,484 Mexican-born individuals in Canada (27,485x 0.6559 x 0.1571 = 2,836) would have lived in rural areas in these three provinces. The actual number of Mexican-born living in these areas was 14,770. The difference is 11,934 and is an estimate of the number of Mexican Mennonites living in these areas. An estimate of the number of non-Mennonite Mexicans living in Canada is 15,551 (27,485 - 11,934). Using the same methodology and the 2001 data, we estimate the number of Mexican-born Mennonites to be 14,012 and the number of Mexican-born non-Mennonites at 22,213.

9 Newer data are available (CIC, 2005) that support the supposition that many Mexican students are taking part in short-term exchange and/or language-training programs. These data show a decline in both the stocks and flows of Mexican students in 2002 and 2003, probably because of the June 2002 Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA). IRPA dropped the requirement that students obtain a visa to enter Canada if they are coming to Study for six months or less.

10 Table 4 shows the dramatic increase in both Mexicans and Canadians admitted temporarily to the United States, while the figures in this table represent admittances and not individuals, as in Table 3, they still show that there has been a dramatic influx of temporary workers to the United States. Thus, the United States continues to be a bigger draw for temporary legal workers from Mexico than is Canada, and both the absolute numbers and the growth rates attest to this fact.

11 Data that show only flows of refugee claimants by country of alleged persecution basically mirror those in Table 10. The exception is the United States, which does not rank in the top ten source countries in the case of refugees; recent increases from that country is likely due to those fleeing military service.

12 The Canadian Council for Refugees compiled these numbers from data supplied by the IRB, the government body that adjudicates refugee cases in Canada. A total of 40,408 claims were finalized, with 16,005 (40%) accepted, 19,108 (47%) denied, 2,809 (7%) abandoned, and 2,4l4 (6%) withdrawn or Otherwise resolved. See www.web.ca/-ccr.

13 Landing data are those collected when immigrants enter Canada for the first time following obtaining permanent resident status. These data can be combined with income data from annual income tax returns to provide researchers with information on the economic experiences of immigrants over time in Canada.

14 Special tabulations by CIC, however, are not available without cost to researchers. Similarly, Canadian census data include Mexicans in Canada but only as part of a group that also includes other Latin American countries. Census data that allow researchers to identify Mexicans in Canada are available only at Regional Data Centres, under Strictly controlled conditions. See Michael G. Abbott (2003), Martha Justus and Jessie-Lynn MacDonald (2003), and Doug Norris (2003) for more details about these data sets.

Información sobre el autor

RICHARD E. MUELLER es profesor asociado de economía en la Universidad Lethbridge, en Alberta, Canadá, y realizó su doctorado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. Ha sido profesor visitante en varias universidades, y sus temas de interés incluyen las causas y efectos de la migración en América del Norte, la discriminación en el mercado laboral hacia ciertos grupos demográficos y los determinantes de la demanda universitaria en Canadá.