Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.2 no.3 Tijuana ene./jun. 2004

Artículos

Connections between U.S. Female Migration and Family Formation and Dissolution

Laura E. Hill *

* Public Policy Institute of California

Fecha de recepción: 21 de abril de 2003

Fecha de aceptación: 14 de julio de 2003

Abstract

Young single women from Mexico and Central America are becoming more numerous in the flow of migrants to the United States. An examination of the retrospective marital histories from the samples of the 1990 and 1995 Current Population Survey shows strong temporal connections between women's international migration and other life-course events, namely, marriage and divorce. For single women born in Mexico or Central America, proportional hazards estimation reveals a much higher likelihood of first marriage during the first years of migration, than before migration. For all migrant women, the likelihood of experiencing a first divorce around the time of migration is greater than at any other time. These findings suggest that decisions about family formation (and dissolution) may be an integral part of the decision to migrate and settle in the United States.

Keywords: international migration, female migration, marriage, Mexico, Central America.

Resumen

Las mujeres jóvenes de México y Centroamérica han incrementado su participación en el flujo de migrantes a Estados Unidos. Un análisis retrospectivo de las historias maritales que se encuentran en las muestras de la Current Population Survey de 1990 y 1995 revela una fuerte conexión temporal de la migración internacional de mujeres con otros sucesos a lo largo de su vida, principalmente matrimonio y divorcio. Para las mujeres mexicanas y centroamericanas solteras, la estimación de riesgo proporcional muestra que hay más altas probabilidades de que contraigan un primer matrimonio durante los primeros años de la migración que antes de migrar. La probabilidad del total de las mujeres migrantes de experimentar un primer divorcio durante el tiempo de la migración es mayor que en cualquier otra ocasión. Estos resultados indican que la decisión de formar una familia (y de disolverla) puede ser una parte integral de la decisión de migrar y establecerse en Estados Unidos.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, migración femenina, matrimonio, México, Centroamérica.

International migration occurs most commonly among people between the ages of 15 and 35. This is also when family formation and, sometimes, dissolution are most likely to occur. because migration and family formation are linked temporally, previous research has addressed the ways in which migration might affect patterns of family formation after arrival in the country of settlement. This article considers an alternative possibility: Family formation and dissolution may motivate women to move and may play a role in determining who eventually settles in the United States.1

Motivations for international migration are rarely considered from a woman's perspective. Most popular discourse and academic research about international migration focus on the comparative economic opportunities for men in the sending and destination countries (see Todaro, 1969, for example). In these models, women move because they are tied migrants (Mincer, 1978), that is, their movement and settlement patterns are the result of husbands' or fathers' decisions. Newer models, such as those that consider family-based risk diversification (Stark, 1991; Taylor, 1986) and the role of social capital (Massey, Goldring, and Durán, 1994; Massey, Alarcón, Durand, and González, 1987), generally do not consider the case of women separately. In the face of mounting evidence that not all female migration is purely derivative of male migration, more recent quantitative research has considered predictors of female and male migration separately, but these studies have not pursued the possibility that the models themselves may differ for women (Davis and Winters, 2001; Cerrutti and Massey, 2001).

Aside from the question of the appropriateness of the models, no data sources provide sufficient detail on potential migrants to empirically test theories of international migration as they apply specifically to women. No sources provide a binational sample and sufficient contextual detail on women's lives to study whether life-course events motivate women's international migration. Despite these constraints, this article considers the connection between migration and family formation, that is, marriage and divorce, among women who have migrated to the United States. I suggest here that women may migrate in order to secure a better quality of life for themselves and their children, which could include not only access to higher wages but also access to marriage markets and freedom from restrictive social environments (including the stigma on divorce). research on the last two motivations is notably absent from empirical work on female migration.

For women, the retrospective marital and fertility histories from the June samples of the 1990 and 1995 Current Population Survey (CPS) indicate the existence of strong temporal connections between international migration and first marriage and divorce. For single women born in Mexico or Central America, proportional hazards estimation reveals a much higher likelihood of first marriage during the year of migration (approximately six months before and six months after), and for a few years afterward, than exists before migration. This pattern differs from that of other foreign-born women. For all migrant women, the probability of divorce peaks soon after migration (although long after migration, the likelihood of divorce again increases somewhat). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that women's decisions to move are not based solely on their fathers' or male partners' economic motivations and that family formation and dissolution play an important role in the selective return migration of women.

Previous Research: Female Migration, Marriage, and Divorce

Research is still relatively rare on motivations for female migration, even though women have always been a substantial part of the migratory flow (Carter and Sutch, 1998). Some studies have suggested that the proportion of female migrants is increasing in relation to all migrants (Marcelli and Cornelius, 1999; Zlotnik, 1998) and certain motivating factors may be more important for women than for men (Davis and Winters, 2001; Cerrutti and Massey, 2001). However, these studies did not consider the possibility that our current models for predicting migration may not be well suited to analyzing the increasing flow of women. Indeed, most data collection focuses on the perspective of the head of the household (who is most often male) and thus fails to measure the context of female migration adequately.

Recent ethnographic research suggests that the proportion of single women is increasing in relation to overall female migrant flows from Mexico and Central America (Smith and Tarallo, 1993; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2001, 1994; Hondagneu-Sotelo and Ávila, 1997a, 1997b). However, it appears that single women who migrate are not necessarily representative of single women in the sending country in general. Many who have migrated: "were either free of, or able to manipulate, familial patriarchal constraints. Most of these women came from relatively weakly bound families, characterized by lack of economic support and the absence of strong patriarchal rules of authority" (Hondagneu-Sotelo,1994:191).

Pierette Hondagneu-Sotelo noted that female orphans and daughters of divorced parents were among the group of single, female migrants she interviewed for her 1994 book (1994:86-92).

This ethnographic research reveals that single women migrate for a variety of reasons: Nearly all the women cited economic reasons and nearly all went to work once they were in the United States. However, further exploration of their decision-making revealed complicated situations. One woman who migrated when she was young did so to escape the spinsterhood her father planned for her. Another almost married, solely to escape her father's control, but then she migrated instead. Other single women migrated to avoid marginalization by their communities. A woman from Mexico described being "pushed aside" by society and denied employment because she was divorced (Smith and Tarallo, 1993:11). Another single woman with a small daughter migrated after people in her hometown accused her of being a prostitute (Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994:87). Fearful of family disgrace, one mother urged her daughter to migrate when the young woman had an abortion after getting pregnant by a married lover (Smith and Tarallo, 1993:12-13).

Traditional economic models of international migration would probably fail to predict the movements of these women. For women who were not wage earners in the homeland, a model that calculates comparative wages in sending and receiving countries would be of little use. Family-based risk diversification strategies cannot predict the movement of women who are attempting to leave the confines of their family of origin. Models based on social networks, however, might have predictive value in those cases (Davis and Winters, 2001; Cerrutti and Massey, 2001) because women without some form of already established social network in the United States are unlikely to migrate (Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994).

Most research on marriage and divorce among migrants relies on data for Puerto Rican-born people living in the United States and both nonmigrants and return migrants living in Puerto Rico. (All Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, a factor that is not present in other studies of migrant behavior.) Using this data, Vilma Ortiz (1996) finds that Puerto Rican women married 18 months or longer are the least likely to move to the United States. being an unmarried or a recently married woman increases chances of migration. Ortiz also finds that 30% of never-married women moving from Puerto Rico to the United States marry after arrival, compared to 15% of women who moved from the United States to Puerto Rico. Similarly, the move to the United States correlates with a stronger likelihood of second marriage than does the move from the United States to Puerto Rico. For never-married migrant Puerto Rican women, Susan G. Singley and Nancy S. Landale (1998) find that the more recent the migration, the greater the likelihood of marriage. In addition, all migrant women are more likely to enter first marriages than are non-migrants residing in Puerto Rico. Both of these findings suggest that migration is associated with increased chances for marriage. Indeed, Singley and Landale conclude that migration might actually facilitate the marital search.

Ethnographic research also shows a relationship between international migration and marriage and provides some insight into why that relationship exists. Maura I. Toro-Morn (1995) found that working-class Puerto Rican women may marry soon after arrival in the United States because they are engaged before they move. The timing of migration and marriage may be conflated because both decisions are undertaken jointly. Other research suggests that women prefer marriages in the United States to those in their place of birth because gender roles are more egalitarian. The poor treatment of wives by husbands in the countries of origin was widely attested to by migrant women:

On a visit to Juan Pablo [Dominican Republic], my cousin saw the way my husband was making me wait on him hand and foot, and the way he'd yell if everything wasn't perfect. She said you didn't see such behavior in New York. She said, "Wait 'til you get there. You'll have your own paycheck, and I tell you, he won't be pushing you around the way he is here" (Grasmuck and Pessar, 1991:147).

[...]

In Mexico, men treat us as if we were slaves... as maids... and here, well my husband has many customs from Mexico... He is Mexican but I don't let anyone treat me the same way I was treated the first time. I tell him [her present husband], "Women have the right to be almost as equal as men, they almost have the same rights, they feel the same" (Smith and Tarallo, 1993:23).

[...]

It's different in El Salvador because there the husband gives the wife money. And if the husband says it's okay to buy a dress then [the wife] buys it, but if it is too expensive then he won't let her. Here women are different, they're more liberal (Mahler, 1995:107).

Ethnographies suggest that Mexican and Central American women may have felt repressed or threatened by the institution of marriage as they experienced it in their home communities. A Mexican woman living in California claims, "In Mexico, they use [domestic violence] a lot, and there is no police to help you out. The police finish you off" (Peete, 1999). This sentiment is repeated by Central American women (Menjivar and Salcido, 2002). However, entering the United States is no guarantee that a woman will no longer suffer domestic violence nor are U.S. marriages free from such abuse. Indeed, as their earning power increased, some Central American and Mexican migrant women reported marital tension and, occasionally, abuse (Menjivar and Salcido, 2002; Hirsch, 1999). However, these women also expressed a sense of power associated with the ability to call the police for assistance.2

In the country of origin, divorce is rarely an option, as one young Mexican woman indicated: "Our mothers have told us we're going to get married, and we have to put up with the brute or whomever we have. That is so engrained in us that divorce really isn't that accessible to us. In our families, there hasn't been a divorce. You have to bear the cross. That's what they have told us since we were small" (Peete, 1999).

It is possible that women who do divorce their husbands, despite the disapproval of families, communities, the Church, and the government, might prefer to start life over in a new country.

Some research indicates that people born in Mexico have lower divorce rates when living in the United States than do Americans of Mexican descent (bean, berg, and Van Hook, 1996).3 but this research does not explore whether migration might be associated with an increased probability of divorce. Qualitative research suggests that divorce might be more common in the United States than in the country of origin because of tension created by a wife's increased earning power, or because when one spouse migrates before the other (as often happens), he or she may start a new family in the United States (Repak, 1995; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994).

Quantitative research using data from Puerto Rico (Landale and Ogena 1995) has investigated the correlation of migration and divorce by using event-history analysis. Controlling for length of the union, longer residence in the United States is positively related to greater chances of union dissolution. Puerto Ricans who have not been to the United States are the least likely to be divorced, followed by return migrants. The group most likely to divorce is the Puerto Rican-born currently residing in the United States. These results may be partially due to selective settlement on the part of divorcées. Those who had migrated to the United States in the year prior to migration were 57% more likely to have dissolved their unions than those who had not migrated in that year (Landale and Ogena, 1995:686). This effect was stronger on informal unions than on marriages, and each additional move increased by 14% the likelihood that the union would dissolve (1995:686). Women who migrate from Puerto Rico to the United States are more likely to have a change in marital status after arrival than are women who migrate from the United States to Puerto Rico (Ortiz, 1996), and Puerto Rican migrant women were more likely to have had a marital disruption prior to migration than were their non-migrant counterparts (Gurak et al, 1987 cited in Landale and Ogena, 1995:675).

Ethnographic research lends support to the hypothesis that family formation and dissolution play an important role in the selective return of women to their countries of origin. Women are unlikely to return to their place of birth in the event that the marriage ends: "The truth is that I don't trust him anymore. If we separate, I'm not going back to Mexico. Here, I can get help. There, I wouldn't get any help [from the government]" (Smith and Tarallo, 1993:32).

Some divorces occur because of the woman's desire to remain in the United States and the man's desire to return to the country of origin. Sherri Grasmuck and Patricia R. Pessar write that five of 18 divorces they observed in their study of Dominican-born women living in the United States occurred when the husband wanted to return and the wife chose to remain. Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo describes a discussion she had with a married Mexican couple about what each would do if they won the lottery. The husband said he would return to Mexico. His wife stated, "Not me! Leave half of your winnings, and I'll stay here" (1994:170).

The recent research discussed above indicates that an increasing percentage of migrants are women, and that single women are an increasing part of the female migrant flow. The probability of marriage increases after migration, and some single women express clear preferences about finding marriage partners in the United States. Divorce also appears to be associated with international migration. By settling permanently in the United States, women have the new freedom to end poor marriages.

Using the Current Population Survey to Study Female Migration

Apart from the Puerto Rican data cited in the previous section, there is no source for studying family formation and international migration that includes data collected in both sending and receiving areas. The Mexican Migration Project (MMP) data, which has been used successfully to test recent theoretical developments in international migration, does not collect the kind of detailed migration and marital histories required for this inquiry. My comparisons of the U.S.-drawn sample of the MMP and Current Population Survey data indicated that the sample may underrepresent single and divorced women, perhaps because the MMP data collection focuses on the head of the household. The research reported on in this article relies on the U.S.-based Current Population Survey (CPS). In the mid-1990s, the CPS added questions that provide new data with which to study international migrants in the United States. Since January 1994, the CPS has always included questions about nativity and the year the individual "came to stay." These questions and the relatively large sample of Mexican and Central American-born immigrants provide a valuable new source of information to describe social and economic aspects of the foreign-born population in the United States. The June 1990 and 1995 CPS elicited detailed marital histories of women only. Nativity data were collected for respondents to the June 1991 Immigration Supplement but not for respondents to the June 1990 survey. However, approximately half of the respondents sampled in June 1990 were sampled again in June 1991.4 The data that result from these three surveys (June 1990, 1991, and 1995) are a sample of approximately 8,500 foreign-born females, 1,800 of whom were born in Central America or Mexico.

Female migrants from Mexico and Central America do not share identical life circumstances, but these groups are similar enough to justify combining them for the sake of the statistical power of the larger sample size, although having to do so is a limitation of the study. The non-indigenous populations from both countries share a common language, religious belief (Catholicism and, increasingly, evangelicalism), and high levels of labor-force participation (Brea, 2003). Undoubtedly, a greater proportion of Central American migrants in the 1980s were fleeing political violence and war than were doing so in the past (Hamilton and Chinchilla, 2001; Chinchilla and Hamilton, 1999), and more Central Americans fled violence than did Mexicans. However, many of these Central Americans were ineligible for refugee status and asylum, which meant that they did not qualify for government assistance. Central American and Mexican immigrant women faced similar economic conditions in the United States. They cross the same border under similar, dangerous conditions (some Central Americans spent considerable time in Mexico before migrating), are quite likely to be undocumented, and they often settle in the same communities and take similar jobs in the United States. Both Mexican and Central American female migrants are heavily concentrated in the service sector, working as domestic workers (Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2001; Menjivar, 1999) or factory workers (Menjivar, 1999).

In addition to the small sample sizes of Mexican and Central American female migrants, which necessitates combination into one group, three additional difficulties exist when using the CPS data to study migration. First, it would be desirable to have a comparable group of non-migrants from the country of origin to serve as a control. Second, the year each respondent "came to stay" in the United States is not known with certainty (although the year of marriage is known).5 In most of the analyses that follow, the year of entry is assigned to the midpoint of the range of dates in which migrants stated that they "came to stay."6 Those who arrived in open-ended intervals (before 1950 and before 1960) are excluded from the analysis. A related concern is that repeat migrants may not interpret the question about when they "came to stay" as referring to the first trip to the United States (this will be addressed be-low).7 Third, the CPS in not designed to sample a representative group of immigrants, and indeed, the sample of migrants in the CPS may not be representative of the foreign-born in the United States: The survey is less likely to include migrants who arrived in the years immediately preceding the survey and illegal immigrants. Nevertheless, undocumented immigrants are clearly among CPS respondents. Jeffrey Passel (1999) estimates that among recent Mexican immigrants in the 1995 CPS, 81 percent were undocumented. Despite its shortcomings, the CPS provides some of the richest data available on women in regard to the timing of family formation and migration.

The Timing of Migration and Marriage and Divorce

Instead of being "tied migrants," casting their lot with a father or husband, women may be motivated to migrate by a desire to find better marriage markets or to improve quality of their marriage or even to have the freedom to escape a dissatisfying marriage. If that is so, then there will be a temporal association of migration with marriage and divorce. In the case of marriage, I expect the association with migration to be more likely to occur after than before migration. Divorce, however, could precede a migration and be a cause for the move, or it could be associated with length of stay in the United States. In particular, I expect these associations to be stronger for those born in Mexico or Central America than for women born in other countries. Mexican and Central American-born women are able to enter the United States more readily and are more likely to have connections to established U.S. social networks, which would increase the likelihood that they could migrate in response to the marital considerations.

In order to examine these associations, first-marriage dates are plotted relative to the date of migration for women aged 17 and older at the time of the survey (Figure 1). These distributions are plotted separately for Mexican and Central American-born women and other foreign-born women.8

For all migrant women, the highest percentage of marriages occurs in the same year as the year of migration although, when the two events occur in the same year, determining their order is impossible. It is evident that many women experience both of these events nearly simultaneously within two or three years before or after migration. Nearly 7% of those born in Mexico and Central America marry in the year that they "came to stay" in the United States compared to about 6% for other migrant women. Comparing the two groups reveals several characteristics. For Mexican and Central American-born women, more first marriages occur soon after migrating than before migration. The percentage of first marriages for Mexican and Central American-born women exceeded the percentage for other foreign-born women in all years after migration until the thirteenth year. The percentage of other foreign-born women who enter first marriages, although less marked at the time of migration, is roughly equal before and after migration. In contrast, the Mexican and Central American group is more likely to marry after migration. Clearly, both marriage and migration are influenced by the age of a woman, and the multivariate analysis in the next section will examine that more closely.

Similarly, the data on divorce reveal a concentration after migration for both groups (Figure 2). The most common year of divorce for migrant women is two years after arrival in the United States and the percentage divorcing in that year is nearly twice as high for Mexican and Central American-born women. In general, these women are much more likely to divorce after arriving in the United States than are other foreign-born women.

The concentration of divorces two years after migration may be the result of the concentration of marriages two years earlier. Approximately 8% of Hispanic women in the United States end their first marriages within two years because of separation, divorce, or death (London, 1991), compared to approximately 12% of Mexican and Central American immigrants. However, it appears that these divorces do not arise from marriages contracted for the purpose of obtaining green cards because approximately 80% of the divorces immediately after migration occur in marriages that began more than two years earlier, that is, before the migration took place.

Proportional Hazards Estimations for First Marriage and Divorce by Age and Timing of Migration

The distribution of family-formation events (marriage and divorce) relative to dates of migration (figures 1 and 2) makes a strong case for the existence of a relationship among them. However, the possibility remains that unobserved factors, which determine the "age" at which each event occurs, drive the results. In the case of marriage, "age" refers to the age of the woman (restricted to ages 17 and older) and in the case of divorce, to the duration in years of the marriage.

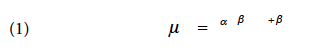

The Cox Proportional Hazards model was used to investigate the hypotheses regarding the timing of women's first marriage and divorce relative to the timing of migration. This method of hazard analysis makes few assumptions about the underlying structure of the data, and it efficiently handles both time-varying covariates and right-censored data.9 The most basic form of the proportional hazards model has the following structure:

The hazard, μx,i, varies by age and for each individual. It is estimated by partial-likelihood methods and is made up of two components: (1) the baseline hazard factor, a, that is dependent on only on the "age" x of the individual, and (2) the factor that does not depend on "age" but rather on the characteristics of the individual, BiXi,i + B2X2,i(t). The first component, the baseline hazard, does not always depend on age. In the estimation of the likelihood of first marriage, "age" measures the duration that a woman remains single from age 17 until first marriage or censoring (the individual's age at the time of the survey). For estimates of the likelihood of first divorce, "age" is number of years the woman had been married at the time of divorce, or if still married, at the time of the survey. The second component can depend on characteristics of the individual that are continuous, discrete, or dependent on time. In equation (1), the BiXi,i term is a vector X made up of time-constant variables and the B2X2,i(t) term can vary over time. These two factors, which are used to determine an individual's hazard at a given "age," are multiplied together. The model incorporates an assumption that the relationships among the covariates are constant over "age" and are independent of one another. They are not necessarily independent of time.

Marriage

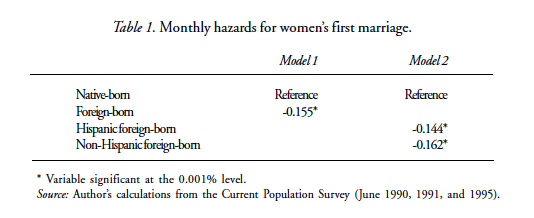

The estimation of proportional hazards for first marriage for all women reveals that immigrant women have a 15.5% lower likelihood of first marriage than do native-born women. Never-married Hispanic foreign-born women have a higher likelihood of marrying than do their non-Hispanic counterparts, but both are less likely to marry than are never-married, U.S.-born women (Table 1).

To estimate the relationship between migration and the likelihood for first marriage, the sample is restricted to migrant women. A series of time-dependent variables captures any connections between migrating and marriage, an innovation used previously only with data for Puerto Rican women. The bivariate results suggest that first-marriage hazards should be higher in the years surrounding the date of migration. Previous research (Landale, 1994; Ortiz, 1996; Singley and Landale, 1998) has been more concerned with either the pre-or post-migration hazards, not both, and has not estimated them simultaneously.

Six time-varying variables designed to capture a particular point in each woman's migration history are included. The primary periods of interest are the year of migration and those years immediately before and after. However, all periods must be estimated to place coefficient sizes in the relevant context. I term these time-varying variables "migration windows." The main time-constant variables are the division of the foreign-born into four distinct groups (Mexican and Central American, Puerto Rican, Other Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic) and a variable constructed to capture any effects of changing migration patterns over the decades due to differences in migration flows. This period variable (migration pre-1980) is interacted with the three Hispanic foreign-born groups because the effects of time may vary depending on place of origin.10

A few variables specific to predicting marriage hazards are also included in the model. Nancy Landale (1994) notes in the analysis of union formation among Puerto Rican women that having already had a child decreases the chances of forming a union. Pregnancy, on the other hand, increases the chances of entering into a union. A time-constant variable to indicate the presence of children and a time-varying variable for the nine months of a woman's first pregnancy are included in the model. Most other variables that would typically be of interest in estimating marriage chances are not available in the CPS. Education, employment, and income are all measured at the date of the survey interview rather than at the time of first marriage, and thus, are not included.

All of the variables mentioned above are included in Model I. Model II also interacts the time-varying migration-window variables with the indicator variable for whether or not the female migrant was born in Mexico or Central America. The results indicate that being pregnant or having already given birth to a child, the two variables not specific to migrants, affect the likelihood of first marriage in the expected directions (Table 2). During the nine months of pregnancy, the likelihood for first marriage increases by nearly 400% (exp[1. 57]=4. 7), the largest impact of any of the variables in the model. Having given birth to a child before forming the first union reduces the likelihood for marriage by nearly 17%.

Mexican and Central American-born women have a higher likelihood of first marriage than do any of the other immigrant groups (Table 2). Puerto Rican-born women have lower hazards of marrying for the first time than does the reference group (although the difference is not statistically significantly). However, this may be due to a higher incidence of informal unions among Puerto Rican women. In the 1980s, one-third of all co-residential unions began without legal marriage (Landale, 1994). Controlling for all other variables, the foreign-born were more likely to experience a first marriage if they had arrived before, rather than after, 1980. It is impossible to tell from this analysis if the decrease in first-marriage hazards for the foreign-born among those arriving after 1980 results from changing marriage markets in the countries of origin or in the United States or both.

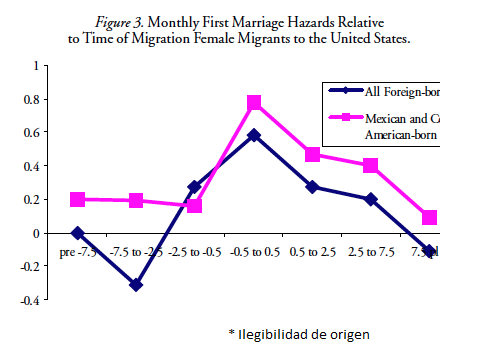

Model 1 reveals that migrants are more likely to marry for the first time in the year that they migrate to the United States. Changes in the monthly hazards for first marriage relative to the date of migration are statistically different from zero for nearly every possible migration period, indicating that the relationship between marriage and migration remains intact even after controlling for age. The monthly hazard of marriage grows as the date of migration nears, it is highest in the year of migration, and it declines with duration of stay in the United States. Most importantly, Model 2 shows that marriages peak in the migration year for all foreign-born women, but only the Mexican and Central American-born women have a higher monthly hazard of first marriage after migration than before (Figure 3).

Although the monthly first-marriage hazards are higher before migration for Mexican and Central American-born women than for other foreign-born women, at migration, the hazards change only for Mexican and Central American-born women. Those for all other foreign-born increase prior to migration. These findings are the same regardless of the reference period.11

Patterns of monthly marriage hazards are consistent with evidence that marriage plays a role in migration decision-making, but this pattern is particularly strong for Mexican and Central American-born women. For the other foreign-born women, the monthly hazard for first marriage is higher immediately before migration. Perhaps other foreign-born women are more likely than Mexican and Central American women to decide to marry and move at the same time. Another possibility is that the greater uncertainty in the precise year of entry for the other migrants means that they are more likely to appear to have married before migrating when they have not. Mexican and Central American-born women are more likely to have "come to stay" in years that the CPS entered two-year-wide bands (49% versus 37%), and the other foreign-born are more likely to arrive in the three- and five-year-wide bands. Indeed, nearly half of the other foreign-born arrived in the United States during years in which the year of entry was coded by the CPS in five- or ten-year-wide bands.

Divorce

Social constraints in the countries of origin may lead divorced women to migrate to the United States. Ethnographic evidence suggests that women find that social ties and employment opportunities diminish for them after divorce (Smith and Tarallo, 1993). Similarly, once in the United States, the freedoms encountered make divorce more viable. The bivariate analyses indicate that the majority of divorces occur after migration.

Proportional hazards estimates for all women show that foreign-born women have lower divorce hazards than do the native-born. The coefficient for non-Hispanic foreign-born indicates that those migrants are only slightly less likely to divorce than are migrant women born in Hispanic countries. As with the estimation of first-marriage hazards, in the case of divorce, the sample is restricted to migrants and the same place-of-birth variables are constructed (Mexico or Central America, Puerto Rico, Other Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic). In addition, the age at marriage and the presence of children are included as predictors.

The Mexican and Central American-born have the lowest hazards for first divorce of any of the four migrant groups, but this coefficient is not significantly different from zero (Table 4, Model 1). Puerto Rican women have the highest likelihood of divorce, followed by the Other Hispanic migrant group. Marrying at older ages suppresses the hazard for divorce, as does having had children. For all groups, the year of migration appears to have no effect on the likelihood of divorce.

The migration-window coefficients in Model 1 show higher likelihoods of divorce immediately preceding and following migration relative to the reference period (at least seven and a half years prior to migration), followed by a decrease after migration and an eventual increase with duration of residence. Model 2 shows that being Mexican and Central American-born has no additional impact on the migration-window coefficients (that is, all the groups of foreign-born have approximately equal probabilities of divorce as duration of residence in the United States increases). Although proximity to the year of migration clearly increases the likelihood for first divorce, chances are higher both immediately before and after the move (that is, the two and a half years prior to and after migration). The hazards are not substantially higher immediately before migration than in other periods, as I had hypothesized. Nor were the hazards clearly higher after migration, as was suggested in the bivariate analyses.

Instead, these results suggest the presence of two groups: those for whom divorce is connected to migration, and those for whom divorce becomes more common as the length of residence in the United States increases. As its member assimilate, they may be influenced by U.S. mores about divorce. Unfortunately, the CPS data cannot tell us whether both members of a couple were residing in the same country at the time of the divorce. Likelihood of divorce increases for all foreign-born women as the time of the move approaches and is highest in the year of the move, but it declines somewhat afterward (although not to the level of the reference period). In the last, open-ended interval, the likelihood of divorce escalates to nearly the level at the time of migration.

Conclusion

Why do we find this strong temporal relationship between the timing of migration and the likelihood marriage and divorce, even after controlling for age and period of arrival? In the case of marriage, three reasons may explain the correlation with migration. First, a marital search could begin after arrival, which may be at least a partial motivation for migration. Second, women may decide to migrate and to marry almost simultaneously (Toro-Morn, 1995). Finally, it is possible that women who marry in the United States are more likely to settle there because they have married citizens (or legalized immigrants), have had children in the United States, or because forming a family in the United States is a proxy for a longer-term connection to American life. In this scenario, women making repeated trips to the United States may report that they "came to stay" at the time of the trip during which they married, and, consequently, settled. Perhaps because they married, they decided to stay. This possibility may be more probable for Mexican and Central American women, who can readily move back and forth between place of origin and the United States. Research on Mexican female migrants suggests that they engage in circular migration, although to a lesser extent than do Mexican men (Reyes, 1997). No comparable data exist for Central American women.

Divorce does not appear to precede migration, contrary to what I had predicted, but instead for one group of women, the likelihood is highest soon after migration, but for another, the likelihood increases with duration of residence in the United States. What causes these distinct divorce patterns?

It seems clear that there are many reasons why divorce and migration might be connected for those divorcing soon after migration. Women may move to the United States after a divorce to secure a chance for a better life in a society that does not sanction divorce. Women who divorce soon after migration may do so because one marriage partner was a "tied migrant" (Mincer, 1978), because of the strain of the move itself, or because the wife moved to the United States (at least in part) to obtain a divorce. Other marriages may end after a woman comes, without her husband, to work in the United States (Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994). Some wives may follow their husbands to the United States after an extended absence, only to discover that the husband has started a new relationship and family, thus prompting a divorce (Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994). Finally, marital stability depends on a successful marital search and on a life without too much uncertainty (Becker, Landes, and Michael 1977). The event of migration certainly involves much uncertainty and many shocks to marriage partners. The large number of marriages begun two years earlier does not explain this group of divorces.

The divorces that occur with duration of residence in the United States could be due to assimilation to U.S. mores regarding divorce, or to selection among return migrants. Perhaps those who remain in the United States would find returning to their place of birth difficult, owing in part to their new social status as a divorcée. Ethnographies cited earlier suggest that some couples divorce when partners disagree about whether to return to their place of birth-men want to return; women want to stay. Another possibility might explain why divorce may increase a few years after migration: A marriage that a couple made while still living in the sending community in Mexico may prove to be poor match for life in the United States. Perhaps after having lived in the United States for a few years, couples decide that they are not suited for each in the United States.

Untangling the remaining questions about why marriage and divorce are so connected to female migration is a task that requires better data. However, the strong association between migration and marriage and divorce suggests that we need immigration models that include more detail on the complexity of women's lives. Certainly, the strong association of marriage and divorce after migration suggests that family-formation dynamics are a crucial element in predicting settlement, return migration, and possibly repeat migration. These findings suggest that women are not simply following husbands and fathers to the United States and that women may move in order to secure a better quality of life, which includes not only access to higher wages, but also access to better marriage markets, access to divorce, and an escape from restrictive social environments.

References

Allison, Paul D., Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide, Cary (NC), SAS Institute, Inc., 1995. [ Links ]

Bean, Frank D., Ruth R. Berg, and Jennifer V. W. Van Hook, "Socioeconomic and Cultural Incorporation and Marital Disruption Among Mexican Americans", Social Forces, 75(2), 1996. [ Links ]

Becker, Gary, Elisabeth Landes, and Robert Michael, "An Economic Analysis of Marital Instability", Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1977, pp. 1141-1188. [ Links ]

Brea, Jorge A., "Population Dynamics in Latin America", Population Bulletin, 58(1), Population Reference Bureau, March 2003. [ Links ]

Carter, Susan B., and Richard Sutch, "Historical Background to Current Immigration Issues", in J. P. Smith and B. Edmonston (eds.), The Immigration Debate: Studies in the Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration, Washington, National Academy Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Cerrutti, Marcela, and Douglas S. Massey, "On the Auspices of Female Migration from Mexico to the United Sates", Demography, 38(2), 2001, pp. 187-200. [ Links ]

Chinchilla, Norma, and Nora Hamilton, "Changing Networks and Alliances in a Transnational Context: Salvadoran and Guatemalan Immigrants in Southern California", Social Justice, 26(3), 1999. [ Links ]

Cox, David R., and D. Oakes, Analysis of Survival Data, New York, Chapman and Hall, 1984. [ Links ]

Current Population Survey (CPS), Fertility, Birth Expectations, and Marital History, Washington, U.S. Department of Commerce-Bureau of the Census, June 1990. [ Links ]

----------, Immigration and Emigration, Washington, U.S. Department of Commerce-Bureau of the Census, June 1991. [ Links ]

-----------, Fertility, Birth Expectations, and Marital History, Washington, U.S. Department of Commerce-Bureau of the Census, June 1995. [ Links ]

Davis, Benjamin, and Paul Winters, "Gender, Networks, and Mexico-U.S. Migration", Journal of Development Studies, 38(2), 2001, pp. 1-26. [ Links ]

Ellis, Mark, and Richard Wright, "When Immigrants Are Not Migrants: Counting Arrivals of the Foreign Born Using the U.S, Census", International Migration Review, 32(1), 1998, pp. 127-144. [ Links ]

Grasmuck, Sherri, and Patricia R. Pessar, Between Two Islands: Dominican International Migration, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Hamilton, Nora, and Norma Chinchilla, Seeking Community in a Global City: Guatemalans and Salvadorans in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Hirsch, Jennifer S., "En el Norte la mujer manda: Gender, Generation, and Geography in a Mexican Transnational Community", The American Behavioral Scientist, 42(9), 1999, pp. 1332-1349. [ Links ]

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette, Domestica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2001. [ Links ]

-----------, Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences of Immigration, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994. [ Links ]

-----------, and Ernestine Ávila, "Transnational Motherhood", paper presented to the Department of Sociology, University of California, Berkeley, October 9, 1997a. [ Links ]

----------, "'I'm Here, but I'm There': The Meanings of Latina TransnationalMotherhood", Gender and Society, 11(5), 1997b, pp. 548-571. [ Links ]

Landale, Nancy S., "Migration and the Latino Family: The Union Formation Behavior of Puerto Rican Women", Demography, 31(1), 1994, pp. 133-157. [ Links ]

-----------, and Nimfa B. Ogena, "Migration and Union Dissolution among Puerto Rican Women", International Migration Review, 29(3), 1995, pp. 671-692. [ Links ]

London, Kathryn A., "Cohabitation, Marriage, Marital Dissolution, and Remarriage: United States, 1988: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth", Advance Data, 194, January 4, 1991. [ Links ]

Mahler, Sarah J., Salvadorans in Suburbia: Symbiosis and Conflict, Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 1995. [ Links ]

Marcelli, Enrico A., and Wayne A. Cornelius, "The Changing Profile of Mexican Migrants to the United States: New Evidence from Southern California", paper presented at annual meetings of the Population Association of America, New York, March 25-27, 1999. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas S., and Nolan Malone, "Pathways to Legal Immigration", paper presented at the annual meetings of the Population Association of America, Chicago, April 2-4, 1998. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas S., Luin Goldring, and José Durand, "Continuities in Transnational Migration: An Analysis of Nineteen Mexican Communities", American Journal of Sociology, 99(6), 1994, pp. 1491-1512. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas S., Rafael Alarcón, José Durand, and Humberto González, Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Menjívar, Cecilia, "The Intersection ofWork and Gender: Central American Immigrant Women and Employment in California", American Behavioral Scientist, 42(4), January 1999. [ Links ]

----------, and Olivia Salcido, "Immigrant Women and Domestic Violence: Common Experiences in Different Countries", Gender and Society, 16(6), 2002, pp. 898-920. [ Links ]

Mincer, Jacob, "Family Migration Decisions", Journal of Political Economy, 86, 1978, pp. 749-773. [ Links ]

Ortiz, Vilma, "Migration and Marriage among Puerto Rican Women", International Migration Review, 30(2), 1996, pp. 460-484. [ Links ]

Passel, Jeffrey S., "Undocumented Immigration to the United States: Numbers, Trends, and Characteristics", in D. W. Haines and K. E. Rosenblum (eds.), Illegal Immigration in American: A Reference Handbook, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Peete, Cynthia T., "The Importance of Place of Residence in Health Outcomes Research: How Does Living in an Ethnic Enclave Affect Low Birth-Weight Deliveries for Hispanic Mothers?", Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1999. [ Links ]

Repak, Terry A., Waiting on Washington: Central American Workers in the Nations Capital, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Singley, Susan G., and Nancy S. Landale, "Incorporating Origin and Process in Migration-Fertility Frameworks: The Case of Puerto Rican Women", Social Forces, 76(4), 1998, pp. 1437-1470. [ Links ]

Smith, Michael P., and Bernadette Tarallo, California's Changing Faces: New Immigrant Survival Strategies and State Policy, California Policy Center/University of California, Berkeley, 1993. [ Links ]

Stark, Oded, The Migration of Labor, Cambridge (MA), Basil Blackwell, Inc., 1991. [ Links ]

Taylor, J. Edward, "Differential Migration, Networks, Information and Risk", in Oded Stark (ed.), Research in Human Capital and Development, Greenwich (CT), Jai Press, 1986. [ Links ]

Todaro, Michael P., "A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less-Developed Countries", The American Economic Review, 59, 1969, pp. 138-148. [ Links ]

Toro-Morn, Maura I. "Gender, Class, Family, and Migration: Puerto Rican Women in Chicago", Gender and Society, 9(6), 1995, pp. 712126. [ Links ]

Welch, Finis, "Matching the Current Population Surveys", Data Management, 11 (Stata Technical Bulletin, 12), 1993, pp. 7-11. [ Links ]

Zlotnik, Hania, "International Migration 1965-1996: An Overview", Population and Development Review, 24(3), 1998, pp. 429-468. [ Links ]

1 The author wishes to acknowledge the generous support of a Predoctoral Training Grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. In addition, this article benefited from comments from Kenneth W. Wachter, Ronald D. Lee, Hilary W. Hoynes, Michael S. Clune, and Cynthia T. Peete, as well as those of anonymous reviewers of an earlier draft. However, any errors are those of the author.

2 This may not be as relevant for indigenous Central Americans, who have more egalitarian unions, in which both partners share in the housework and family decision-making and participate in the labor force (Menjivar, 1999).

3 I was not able to find similar quantitative research on Central Americans.

4 Details are available from the author upon request, but also see Welch (1993) for technical documentation.

5 The year and month of marriage are recorded, but only broad time frames for the year a foreign-born individual "came to stay" are recorded. The same practice is followed in the United States Census. Sixty-five percent of Mexican and Central American women arrive in intervals of uncertainty no more than three years wide. The same is true for 52% of women born in other countries.

6 Assuming equal probabilities of entering the country over the interval in question produced nearly identical results.

7 Migrants who have entered repeatedly may not consider their first trip the one in which they came to stay. This question is subject to interpretation on the part of the respondent. Massey and Malone (1998) show that a high percentage of migrants applying for legalization have been to the United States repeatedly before their current trip and Ellis and Wright (1998) use Census data to show that some migrants were living in the United States before they "came to stay."

8 Years of entry are smoothed by assuming equal probabilities of entry over all possible dates.

9 See, among others, Cox and Oakes (1984) and Allison (1995).

10 More detailed investigations of possible period effects revealed no consistent patterns.

11 Analyses that treat each year separately, and thus have all other years as the reference period reveal similar patterns. No reference period choice changes the general pattern.