Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.2 no.3 Tijuana ene./jun. 2004

Artículos

Migration Strategies in Urban Contexts:

Labor Migration from Mexico City to the United States

Fernando Lozano Ascencio *

* Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Fecha de recepción: 1 de marzo de 2004

Fecha de aceptación: 28 de mayo de 2004

Resumen

La acelerada urbanización de la sociedad mexicana es un proceso fuertemente asociado a la creciente participación de población de origen urbano en el flujo migratorio hacia Estados Unidos. Esta "urbanización" del flujo laboral internacional ha promovido cambios en el perfil de la migración mexicana hacia Estados Unidos. El presente artículo examina la dinámica social de la migración internacional en contextos urbanos, particularmente en la zona metropolitana de la ciudad de México (ZMCM). Con base en la perspectiva de los sistemas migratorios, el artículo explora la forma en que opera la migración internacional en dicha ciudad y las diferentes estrategias migratorias adoptadas por los migrantes de ella. Se analizan las características socioeconómicas y demográficas de los individuos incluidos en la encuesta de la ciudad de México (levantada por el autor), sus patrones de migración interna e internacional y las características generales de su experiencia migratoria a Estados Unidos. Finalmente, se presentan algunos resúmenes biográficos que ilustran distintos patrones migratorios desde la ciudad de México.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, patrones migratorios, migración urbana, ciudad de México, Estados Unidos.

Abstract

The progressive urbanization of Mexican society is a process strongly associated with the increasing participation of the urban-origin population in the migratory flow to the United States. The "urbanization" of this international labor flow has changed the profile of Mexican migration to the United States. This article examines the social dynamics of international migration in urban contexts, particularly in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Based on a migration systems perspective, the article explores the way that international migration operates in Mexico City and the different migration strategies pursued by migrants from this city. The article analyses demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of individuals in the Mexico City survey (conducted by the author) as well as their patterns of internal and international migration, and the general characteristics of their U.S. migration experience. Finally, it presents some biographical sketches to illustrate the various patterns of migration from Mexico City.

Keywords: international migration, migration patterns, urban migration, Mexico City, United States.

Introduction

The accelerated urbanization of Mexican society over the last three decades is a process strongly associated with the increasing participation of the urban-origin population in the migratory flow to the United States. Urban migrants not only include those who were born in the cities, but also people from rural areas who have migrated and settled in Mexican cities. The "urbanization" of this international labor flow has changed the profile in Mexican migration to the United States. Several authors have documented, among other changes, a shift from temporary to longer-term migration, the incorporation of new Mexican states and metropolitan areas as sending regions, the presence of more women among migrants, and in general a more educated migrant population (Alba, 1985, 1994; Bean et al., 1990; Cornelius, 1992; Corona, 1998; Lozano-Ascencio, 1998, Marcelli and Cornelius, 2001; Papail, 1998).

The existing body of research on Mexican migration to the United States has concentrated mainly on Mexican rural communities. Most of the theoretical approaches explaining international Mexican migration are based on studies from rural areas. However, the social dynamics of migration from urban contexts, and particularly, from major cities, are sufficiently different from those of smaller towns to warrant separate study (Lozano-Ascencio, Roberts, and Bean 1997).

This article analyzes the social dynamics of international migration in urban contexts, particularly in the Mexico City metropolitan area. Based on a migration systems perspective, the article explores the way in which Mexico City international migration operates, and the different migration strategies that Mexico City migrants pursue. After a brief reflection on migration systems, the article examines the growing presence of Mexico City migrants in the international flow to the United States, and presents the methodology employed in the fieldwork. Next, the article analyses demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of individuals in the Mexico City sample, their patterns of internal and international migration, and the general characteristics of their U.S. migration experience. Finally, it presents some biographical sketches to illustrate various patterns of migration from Mexico City.

Reflections on Migration Systems

At the basis of the systems approach to the study of international migration is the concept of a migration system constituted by a group of countries that exchange relatively large numbers of migrants (Kritz and Zlotnik, 1992). Those who use this approach argue that, at a minimum, a migration system includes at least two countries, although, it is possible to include in a system all countries linked by large migratory flows. In a specific migration system, population exchange involves permanent migrants, migrant workers, refugees, students, businesspeople, and tourists, all of whom eventually become involved in labor flows.

Extending on this migration system approach, colleagues and I have suggested that Mexico-U.S. migration is based on three migration systems: temporary, permanent, and transnational (Roberts, Frank, and Lozano, 1999). Each is defined by specific social and economic structures in the places of origin and destination, which reproduce particular patterns of migrant behavior, and each has distinct implications for the adjustment of Mexican migrants to the United States. When these structures complement each other, they create a migration system.

A temporary migration system rests on a structure of economic opportunities in the place of origin that, although insufficient for the full subsistence of a household, nonetheless can maintain a family if one or more members of the household become labor migrants. The temporary nature of this labor migration is reinforced by a structure of opportunities in the place of destination that provide work opportunities that is also temporary, either because of the nature of the job (as in seasonal agriculture) or because of official restrictions on permanent stay. Several studies, particularly those in central-western Mexico, have documented that market-oriented, semi-subsistence agriculture and the demand for temporary labor—particularly in Californian agriculture constituted the basis of the historic temporary migration system between Mexico and the United States (Cornelius, 1990; López, 1986; Mines, 1981; Massey et al., 1987).

A permanent migration system rests on the lack of economic opportunities in the place of origin and the attraction of permanent work opportunities in the place of destination. The more abundant and stable the work opportunities at the destination, and the fewer the legal barriers to obtaining them, the stronger the permanent migration system will be. Structural problems in the Mexican economy, such as low salaries, in addition to the U.S. demand for year-round, low-skilled labor in industries such as construction and urban services, create the basis for a permanent migration system.

A transnational migration system is based on the interrelationship between opportunities in places of origin and places of destination. According to Nina Glick Schiller, Linda Basch, and Christina Szanton-Blanc, transnational migration "is the process by which immigrants forge and sustain simultaneous multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement" (1999:73). People who participate in this kind of migration are not sojourners; they settle and gradually participate more and more in the economy and political institutions of the host country. At the same time, however, they maintain social and economic connections with their country or community of origin, by sending money, building institutions, and participating in local and national events. Many scholars have documented a variety of transnational migration forms between the United States and different sending countries, including Mexico (Rouse, 1992; Smith, 1995) or the Dominican Republic (Guarnizo, 1993), and between European receiving countries and their sending states (Faist, 1999).

The three systems of migration operate simultaneously to shape Mexico-U.S. migration and are by no means mutually exclusive. They are likely to be associated with differences in the individual characteristics and social networks of rural or urban migrants. Larissa Lomnitz (1976) defines a social network as a structured set of social relationships among individuals, and M.S. Granovetter (1973) makes a useful distinction between strong and weak ties in social networks, and suggests that strong ties consist of those in which there are important emotional linkages and/or frequent, routine interactions. Strong ties are similar to primary relationships, usually built among kin and friends. Weak ties lack emotional strength and include specialized contacts within formal organizations, or between clients and service providers. Strong ties are usually associated with strong communities; strong ties imply the existence of a solid social participation and cohesion of community members (Granovetter, 1973).

The three systems of migration are closely associated with specific social networks. For example, migrants from villages or small towns are more likely to be part of either a permanent or a transnational migration system. Although their local ties are strong and the possibilities of investing and influencing community development are high, it is difficult from them to subsist at home without continuing year-round income from abroad. This makes the temporary migration strategy less workable than in the past. Conversely, migrants from the cities are more likely to be temporary or permanent migrants, because community ties are weak and the possibility of contributing to local development is low, and the cities have economic opportunities to which migrants can return and in which they can invest their migrant earnings.

Whereas one can find substantial evidence concerning the motivations behind rural migrants in promoting and engaging in transnational migration, very little work has been done to evaluate the options facing urban migrants and the different patterns of migration they follow. This article explores the relatively recent nature of urban-origin international migration, particularly in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area.

Trends in Migration from Mexico City to the United States

The Mexico City Metropolitan Area completely covers the Distrito Federal, 37 municipios in the Estado de México, and one municipio in the state of Hidalgo, and it has a population of 17.9 million, or 18.4% of the total Mexican population nationwide (2000 Census). These figures reflect the intense inmigration in Mexico City over the course of the twentieth century, motivated by the concentration of infrastructure; urban services; political, industrial, and financial activities; and healthcare, educational, and cultural facilities (Pick and Butler, 1997).

During the twentieth century, Mexico City's population grew from 345,000 in 1900 to one million in 1930, 3 million in 1950, 8.6 million in 1970, 15 million in 1990, and 17.9 million in 2000. The most rapid and continued growth occurred from 1940 to 1970, when the population grew by more than 5% annually. The growth rate declined to 4.4% between 1970 and 1980, to 0.7% in 1980 to 1990, and presented a slight recovery to 1.7% in the period 1990 to 2000.

In demographic terms the abrupt decline in Mexico City's growth rate after 1970 was due to fertility decline, decline in inmigration, and increase in out-migration. However, government policies calling for decentralization of public and private enterprises, the prohibition of new industries in the Valley of Mexico, the 1985 earthquake, together with growing quality-of-life issues, environmental degradation, and public safety concerns, have been central factors in the slowing expansion of the city. Associated with those transformations in the internal migration pattern is a significant rise in migration to the United States, which started in the 1980s and intensified during the 1990s. Both were central factors for selecting the Mexico City Metropolitan Area as the site to explore the operation of urban-origin migration and its contribution to international migration.

The participation of migrants from Mexico City in the international flow to the United States has changed significantly over the twentieth century. In this section I examine the evolution of Mexico City migration to the United States, as can be seen in an examination of 12 nationally representative surveys (see Table 1). In the description of these surveys, I decided to include both Distrito Federal and Estado de México considering that at the end of the century, 37 municipalities of this state were part of the Mexico City Metropolitan Area.

Using data from the Dirección General de Correos de México (Mexican Postal Service), Manuel Gamio (1930) studied money orders sent from the United States to Mexico during July and August 1926. He found that Distrito Federal and Estado de México received 5.3%. Gamio assumed that postal money orders originating in the United States and destined for the Republic of Mexico were sent by migrants to their families, which led him to identify places of origin and destination of migratory flows between the two countries. However, there is not enough evidence to assume that 5.3% of migrants were Mexico City-origin migrants.

According to Mexican Government statistics, in 1944, a quarter of U.S. temporary agricultural workers were from Mexico City. However,this does not necessarily mean that these agricultural migrants were permanent residents of the city. The Distrito Federal was one of the most important recruitment centers for the Bracero program, and migrants from the surrounding states moved to Mexico City to sign up (Durand, 1994). Although the Mexican Government statistics seem to indicate that Mexico City was an important provider of international migrants, the city functioned mostly as a transit point for rural-origin migrants from the central region of Mexico.

During the 1970s, Distrito Federal and Estado de México show very low rates of international migration. Based on interviews with Mexicans deported by U.S. authorities along on Mexico's northern border, the Comisión Intersecretarial para el Estudio del Problema de la Emigración Subrepticia de Trabajadores Mexicanos a los Estados Unidos de América (Inter-Ministry Commission for the Study of the Undocumented Mexican Migration to the U.S.) found in 1974 that 4% of migrants were Distrito Federal and Estado de México residents and in 1975, 3.6% were from the same two states. Following the same methodology of using interviews among Mexicans deported by U.S. authorities, the Centro de Información y Estadísticas de Trabajo (Center for Labor Information and Statistics) found that in 1977 and 1978, 4.6% and 3.8% of migrants were Distrito Federal and Estado de México residents. Notably, during the 1970s, the participation of migrants from the Estado de México barely surpasses 1% of the total, a situation that changed radically in the next decade.

The last six sources presented in Table 1 illustrate the growing presence of MCMA residents in the migratory flow to the United States. In 1984 the Mexican National Population Council coordinated a survey of undocumented migrants along Mexico's northern border, which found that 5.1% were living in Distrito Federal and Estado de México before migrating to the United States. The Legalized Population Survey (LPS1) and the follow-up survey (LPS2), which were conducted among U.S. immigrants legalized under the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1989 and 1992, found that 7.5% of the respondents were from Distrito Federal and Estado de México.

By 1992, the Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica (National Survey of Demographic Dynamics, ENADID) found that return and absent migrants from Distrito Federal and Estado de México constituted 9.4% of the migrant population. Indeed, 1992 is the first year that migrants from these two states were the third largest group, surpassed only by Michoacán (14.8%) and Jalisco (11.8%). The Conteo95 survey, a representative sample of 80,000 Mexican households conducted during November and December of 1995, showed that 9.6% of return and absent migrants (defined as those return and absent migrants who were working or looking for a job in the United States during the five-year period prior to the survey) were living in the Distrito Federal and the Estado de México. This growth trend continued into 2000, when both states sent the 12% of all Mexican migrants to the United States.

Notably, the participation in the international flow to the United States by migrants from the Estado de México becomes significantly high in 1992, 1995, and, particularly, in 2000.1 Nonetheless, Distrito Federal migrants alone are increasingly participating in the international labor flow to the United States, a process that reflects a powerful change in the international migration pattern: the incorporation of new states and new urban areas to this international flow.

Data Collection and Description of the Sample

A survey of 60 Mexico City residents with international labor experience in the United States was conducted between May and August 1998. The analysis centered on two questions: (1) What is the urban experience that promotes international migration? And (2) what are the social and economic strategies employed by residents of Mexico City in the migration process to the United States? Intensive interviews were conducted to understand the extent of international migration from Mexico City, the effects of the Mexican economic crisis on the internal and international migration, and concentrations of international migrants in specific barrios or colonias. Key informants included migration specialists, political leaders, city government officials, and leaders of grassroots neighborhood organizations. The general finding of these preliminary interviews was that migrants were not concentrated in any one area of the MCMA, even in neighborhoods such as Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl that traditionally have sent migrants to the United States. So, I faced the problem of locating migrants with international-migration experience in a metropolis of 18 million people.

I solved this by using grassroots neighborhood organizations to contact potential interviewees, and then, using the snowball technique, through which those interviewees suggest other potential interviewees (Wolcott, 1995). I interviewed men and women at different life-cycle stages and people from the working class (manual and low-skilled workers), as well as middle-income workers and professionals (public employees, clerical workers, employees of small businesses, and teachers). Interviewees came from two areas inside the MCMA: the "Center Zone" (as I call it) has a population with a high proportion of native residents whereas the barrios and colonias of the "Periphery Zone" (also my label) have a high proportion of non-native Mexico City residents.

Using grassroots neighborhood organizations to find potential interviewees proved useful because most of these organizations have members with international-migration experience. One of the central goals of these organizations is to get housing for their affiliates, and migration to the United States is a good option for many people to get "quick" money to buy or build a house.

The survey questionnaire was divided into six sections: (1) so-ciodemographic information about the household members, (2) family background, (3) labor and migration history, (4) labor market experience in the United States, (5) socioeconomic conditions in Mexico, (6) respondents' attitudes and opinions about life, social and civil rights in Mexico and in the United States. Open-ended questions were used extensively in order to allow full exploration of a number of significant topics.

Contemporary Migration Patterns from Mexico City to the United States

Based on data gathered from interviews with 60 MCMA residents who were either active or former migrants with international experience, we can analyze here the different migratory patterns that characterize this sample. Information was collected from individuals living in seven different Distrito Federal delegaciones and five municipios in the state of Mexico, with 35 individuals from the Central Zone and 25 from the Periphery Zone.2

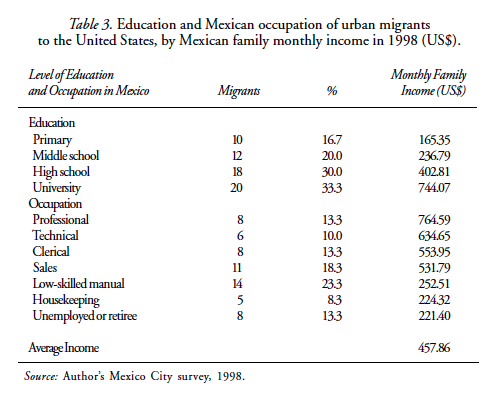

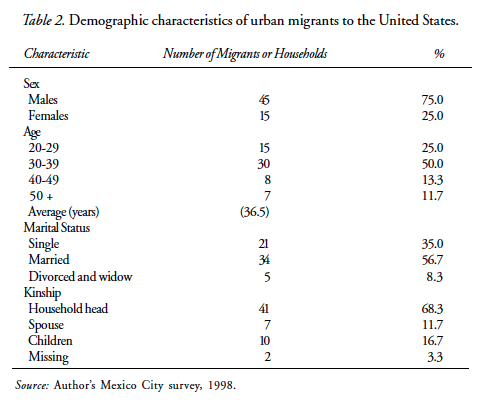

Demographic and socioeconomic profile. Of the interviewees, 75% were men (45 cases) and 25% women (15 cases). Half were between 30 and 39 years old, with the average for the group being 36.5 years. Most (57%) were married; 35% were single, and 8% were divorced or widowed. Regarding position in the household, 68% were household heads, 12% spouses, and 17% children (Table 2). The interviewees possessed considerable formal education: 17% had completed primary school, 20% middle school, 30% high school, and 33% had college-level educations (Table 3). The average number of years of schooling was 11.3, which could indicate an over-representation of middle-class individuals. Concerning occupations and family income, 23% of respondents were professionals or technical workers, 32% clerical and sales workers, and 23% low-skilled manual workers. The remaining 22% were housekeepers, retirees, or unemployed. Monthly family income averaged about US$460, ranging from $221 for retirees and the unemployed to $765 for professionals. As expected, those living in the Central Zone had more education (12.3 years) than their counterparts in the Periphery (9.8 years). Differences in educational levels by zone were consistent with differences in family income, as migrants living in the Center earned an average of US$563 per month compared to $322 per month for migrants in the Periphery.

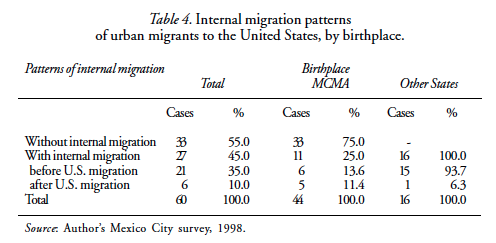

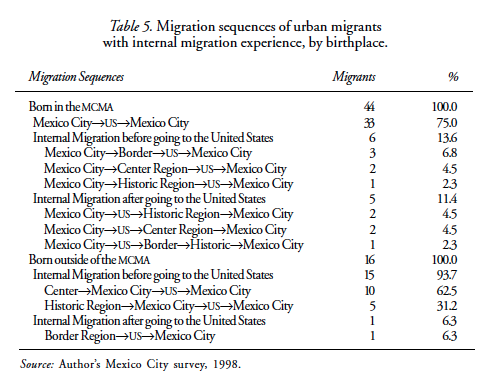

Migration Sequences. Not surprisingly in a region with a high presence of internal in-migrants, I found that 27% of Mexico City respondents were born outside of the metropolitan area (Table 4).3 This statistic is consistent with the population distribution by place of birth in the Distrito Federal in 2000: 75% born in Mexico City and 25% born outside the city. However, these numbers are not consistent with the distribution of native and nonnative population by state of residence in some international migration surveys. For example, 1992 ENADID data show that 71% of return migrants living in the Distrito Federal at the time of the survey were non-natives (see INEGI, 1994). According to ENADID, the percentage of non-native return migrants in the Estado de México was 66%. On the other hand, the U.S. Legalized Population Survey (LPS) data show similar trends (see LPS, 1996). According to this source, 63% of the legalized population from the Distrito Federal was non-native, as was 60% from the Estado de México. Thus, ENADID and LPS data confirm that around two-thirds of international migrants from these two states migrated first to the Distrito Federal or the Estado de México, and after that, moved to the United States. Our data indicate that, in addition to the 27% who were born in another state, 18% of the MCMA natives moved inside the country before or after migrating to the United States. This last figure elevates the share of respondents with internal migration experience to 45%.

The data indicate that of the 44 interviewees who were born in the MCMA, 25% had both internal and international migration experience, whereas 75% had migrated only internationally. Considering only the group with internal migration experience, more than half had undertaken interstate migration within Mexico before going to the United States and slightly less than half had after going to the United States (Table 5). In the subset that migrated internally before migrating internationally, most had initially moved to a Mexican state in the northern border region. They then migrated to the United States, and finally moved back to Mexico City. Migrants in this type of sequence do not necessarily move to the border in order to migrate to the United States. However, once at the border, they gather information about the labor market in the United States, and eventually decide to migrate (Lozano-Ascencio, Roberts, and Bean 1997).

The case of César Delgado is typical of this type of sequence. Delgado was born in 1968 in the Colonia Ramos Millán, Delegación Iztacalco, Mexico City. Since he married at an early age and immediately began to raise a family, he only completed secondary school. At 16, he became a manual laborer in a garment factory. At 17, he moved alone to Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, to work in a hardware store. One year later, he moved back to Mexico City and continued working in the garment sector. Three years later, in 1989, he moved to Rosarito, Baja California, where he worked in a passenger-elevator business for a year. In 1990, following the advice of his brother-in-law, Delgado migrated to Los Angeles, California, where he worked in a furniture factory for four years. During that time, his wife and his two children lived with him. In 1993, the whole family moved back to Mexico City, where Delgado worked as a clerk in a hotel. He migrated to the United States twice. Between June 1995 to December 1996, he worked in Los Angeles in the same furniture factory. Finally, from March to August 1997, Delgado traveled to San Francisco, California, where he joined one of his brothers. In San Francisco he worked as a driver in a valet parking business and as a handyman in a restaurant. He now lives in the Delegación Iztapalapa, Distrito Federal, but he is unemployed. However, if he finds a good job in Mexico—not necessarily in the MCMA—Delgado would cease making temporary trips to the United States.

All migrants in the subset that migrated internally after migrating internationally, had been born in the MCMA. Their migratory sequence began with a move directly to the United States, without any migrations within Mexico. After time abroad, instead of returning to the MCMA, they moved to a different state inside Mexico. Finally, they moved back to their place of origin, that is, to the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. In regard to destination within Mexico, I did not find any particular pattern (see Table 5).

In our sample, 16 migrants were born outside the MCMA: ten in the south-central region, five in the historic region, and one in the border region.4 The most frequent migration sequence I found among nonnative migrants includes individuals born in the south-central region, particularly in the states of Hidalgo, Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Puebla. Those migrants moved first to the MCMA, then to the United States, and finally back to Mexico City. The other significant migration sequence includes individuals born in the historic region, particularly Guanajuato, Jalisco, and Michoacán, who migrated to Mexico City, and then to the United States, before returning finally to Mexico City.

One-quarter of the sample's migrants were "step-migrants," who had first moved to Mexico City and, subsequently, to the United States. Thus, our data support the argument of Wayne Cornelius' (1992), who claims that Mexico City is not only absorbing internal migrants from the countryside and provincial cities but also serves increasingly as a platform for migration to the United States. Although many migrants experienced sequences that combined internal and internal migration, the majority of Mexico City migrants (55%) migrated only to the United States, and did not experience any type of internal migration.

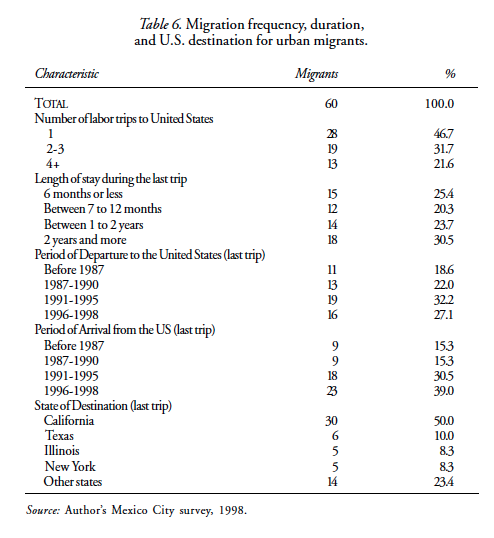

Migration Frequency, Duration, and Destinations. Almost half (47%) of the Mexico City sample made only one labor trip to the United States, while 32% made two or three trips, and 22% made four trips or more trips during their migration career. However, migration frequency per se does not indicate any particular migration pattern. To establish those patterns, one must combine information about the number of trips, their duration, and when they were made. Focusing on the characteristics of a migrant's final trip, about 46% of respondents stayed in the United States up to one year. One-fourth stayed for one to two years, and 31% stayed more than two years. The mean length of stay in the United States was 22 months, and the median stay was 15 months. These high average lengths of stay may indicate that metropolitan migrants are less involved in seasonal than in year-round occupations (that is, full-time work), which reduces the frequency of their temporary labor migrations. We interviewed both active and non-active migrants. About 30% of respondents ended their last migration before 1990, and 70% ended their last migration during the 1990s. During the final trip, 50% of the respondents migrated to California, 27% to Texas, Illinois, and New York; and the remaining 23% migrated to eight other U.S. states. These migrants went 24 U.S. cities: 25% were concentrated in Los Angeles, 30% in New York City, San Francisco, Dallas, and Chicago, and 45% in the other 19 cities.

A Typology of Migrants

Information about migration frequency, duration of residence in the United States, and departure and arrival time for the final labor trip are central in the definition of migration typology. Alejandro Portes (1997) argues that typologies are valid intellectual exercises, but they are not theories because drawing a distinction between different migrant groups does not tell us anything about the causal origins of each flow or its particular pattern of adaptation.5 In short, these typologies are merely methodological instruments to aid in the examination of the different migration strategies.

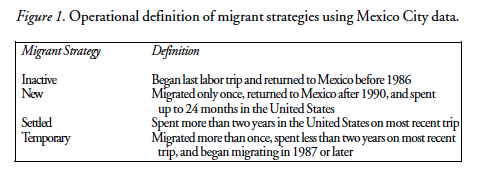

Based on definitions suggested by Douglas Massey and his co-authors (1987), I developed a scheme for classifying strategies employed by migrants in the Mexico City sample (Figure 1). In this scheme, inactive migrants are defined as those who have not migrated for at least 12 years and who, we can expect, will not migrate again to the United States. New migrants are defined as those who have migrated only once during the 1990s, spending up to two years in the United States, whereas settled migrants spent two years or more on their most recent trip there. Finally, temporary migrants have migrated more than once, they spent less than 2 years in the United States on most recent trip, and began migrating in 1987 or later.

The temporary migrant group is the most diverse and complex. It includes people with recurrent migration patterns, that is, cyclical migrants with regular periods of stay in the United States. The temporary group also includes those migrants who exhibit erratic migration patterns. For example, in this group there are those who move initially for non-economic reasons (perhaps just for the experience), but who eventually take a job in the United States.

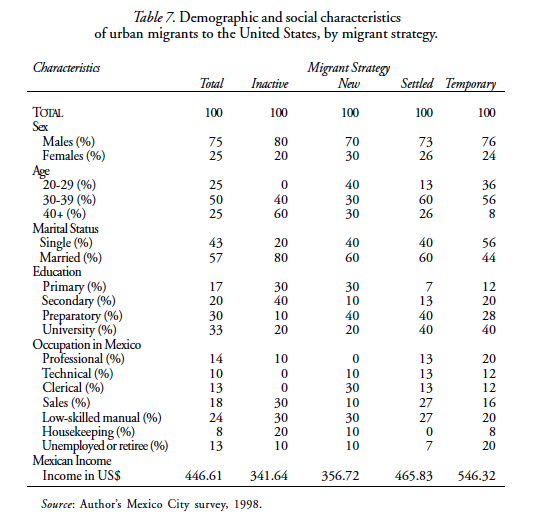

The demographic and social characteristics of the four groups merits examination (Table 7). The sex ratio in all four groups is similar: about three men for each woman. As we expected, inactive migrants are concentrated in the oldest age group (40 years or older), new migrants in the youngest (between 20 and 29), and settled and temporary migrants are in the middle (30 to 39). Regarding marital status, 56% of the temporary migrants are single compared to 43% for all respondents. Although the educational level in the sample population was high (63% of respondents had attended high school or college), among settled migrants that increases to 80%. In terms of the occupation and family income in Mexico, when compared to other types of migrants, temporary migrants are more likely to be professional or technical workers, and less likely to be low-skilled manual workers than, which may explain why they have higher family incomes on average. Temporary migrants are also the most likely to be unemployed or retirees.

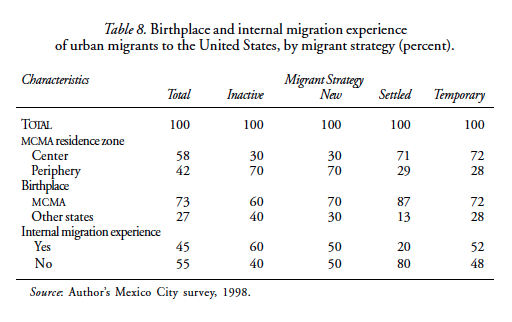

Our data show that migrants who were born in the MCMA have a higher propensity to participate in the settled migration pattern than those born outside the MCMA (Table 8). Settled and temporary migrants tend to live in the Center Zone of the MCMA, and settled migrants tend to have considerably less internal migration experience. Thus, people participating in the settled migrant strategy move directly to the United States without first going to internal destinations.

Cases of Migration Strategies

The Mexico City fieldwork identified three types of migration strategies: new, temporary, and settled. Case studies illustrate the nature of each.

New Migration. Víctor Manuel, 34 years of age, is a "new" migrant from the Periphery Zone. He has made only one trip to the United States in his lifetime. Born in 1964 in Colonia Obrera, Distrito Federal, Víctor Manuel is the second of three children. His father was born in Hidalgo, and his mother in Veracruz. Since he was 8 years old, he had lived in Delegación Iztapalapa, and he had never moved, even within the city. At age 17, he began working at an electronic-parts factory, while continuing to attend high school. Víctor Manuel earned his bachelor's degree in psychology, and as soon as he left the university, he got a job at the Mexican Ministry of Health, where he worked for ten years. Although Víctor Manuel is university trained, he does not work in the field of psychology but instead has an administrative job that pays US$300 per month.

In January 1998, Víctor Manuel asked the Health Ministry for a six-month leave without pay and he entered the United States on a tourist passport. His primary motivation was to earn some extra money. However, he also wanted to visit his sister, in Oklahoma, and his brother, in San Jose, California, both settled migrants. He first spent three months in Oklahoma, working in an automobile assembly plant. Then he went to San Jose, where he worked in a food-processing factory. He left the United States on the day his tourist visa expired, exactly six months after he first entered. He wanted to keep a good record with U.S. immigration authorities so that he could return in the future. Although he felt his U.S. salary was good%and considerably higher than his salary in Mexico—he said he definitely would not work in the United States again.

Manuel's experience reflects the situation of many Mexican migrants who have made only one labor trip to the United States. Working with data from the Encuesta sobre migración en la Frontera Norte (Survey on Northern Border Migration, EMIF), Rodolfo Corona found that 34% of all Mexicans interviewed at the U.S.-Mexico border, as they were traveling back to Mexico, had migrated to the United States just once during their lifetime (Corona, 1998).

Temporary migration. Hugo Torres, 35 years old, was born in the rural town of Epazoyucan, Hidalgo, Mexico. He attended school there, until the sixth grade, and then, at the age of 13, he moved to Tepito, a traditional working-class neighborhood in Mexico City. There, he started his own business, buying and selling used merchandise. His immediate family had no tradition of migration to the United States. However, in 1994, when he was 32, one of his cousins invited him to go to the United States, and he went, because "the economic situation in Mexico was extremely difficult." This first international trip took him to San Diego, California. He crossed the border as an indocumentado, avoiding a customs or immigration inspection. Torres spent five months in San Diego and later he returned for 18 months. Both times, he worked as a dishwasher earning US$4.25 per hour. His goal in migrating to the United States was to save some money to buy a car and a house in Mexico. Although he has no intention of settling in the United States, Torres is planning another trip there. This time, he will go to Texas, where he believes there are more jobs. His migration strategy reflects his desire to supplement his Mexican income.

Margarita Robles, 39 years of age, was born in Mexico City. She is indicative of a group of skilled and professional migrants (including high-school teachers, accountants, lawyers, and medical doctors) who increasingly migrate temporarily to the United States. An important characteristic of this group of migrants is that they are unable to practice their professions in the United States, and therefore their U.S. jobs are likely to be in low-skilled occupations. Robles is the single mother of a four-year-old child, and she lives with her mother and two sisters in Colonia San Rafael, in the middle of the MCMA Central Zone. Robles studied in the Chemistry Department at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where she received her bachelor's degree. In 1983, the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) hired her, and she worked there for five years. Later, in 1988, following the advice of a friend, she migrated to Los Angeles, where she worked as a housekeeper in a hotel and as a cook at Taco Bell. Although she only earned US$4.75 per hour, by working two jobs an average of 15 hours per day, she saved US$10,000 in 15 months. That money allowed her to make a down payment on a house in Mexico. Despite the amount of money she made, Robles said she would not migrate permanently to the United States. However, she would go again temporarily, "just to have some money, and go back to Mexico."

Although Torres and Robles belong to different social classes, their migration experience is similar, partly because the U.S. labor market tends to homogenize the jobs that Mexican immigrants can obtain. Neither Torres nor Robles belong to families accustomed to migrating to the United States, and they chose to migrate temporarily because they retain a social and economic interest in Mexico. International migration is a survival strategy that allows them to generate additional financial resources.

Settled migration. Claudia Moreno, 40 years of age, represents the group of migrants who have settled in the United States, returning to Mexico only after several years. Moreno was born and raised in the Distrito Federal. She is the fourth child in a family of nine siblings. After completing middle school, she pursued a technical degree in a business school. Since the age of 14, she has worked in different jobs, mostly in white-collar occupations. Her most stable job was at a Mexican government office (ISSSTE), where she worked for twelve years. At 25, Moreno married and had two daughters. She never had a good relationship with her husband, and she divorced him in 1989. By then, she was 30, and she needed a better paying job in order to support her children. However, despite her substantial experience as an administrative assistant, she could not find employment in Mexico. In Moreno's own words:

For a single mother, for a divorced woman, like me, with two children, it is so difficult to find a job in Mexico. You can find a job but with a very low salary. Moreover, if you are 30 or 32, you are too old for most businesses. So, the only possibility is to have two jobs, but in that way you won't have enough time to share with your children.

In 1990, Moreno decided to migrate to the United States permanently, taking her two children with her. Five out of eight of Moreno's siblings were residing permanently in the United States, three of them since mid-1970s. So, although she had never worked in the United States, she had made four short trips to visit family members, which helped her decide where she would live. Using a tourist passport, she first flew from Mexico City to Los Angeles to stay with an uncle who lived in Ventura. As soon as she arrived, Moreno felt that Los Angeles would not be a good place to settle. She borrowed an old car from her uncle and drove north to Chehalis, Washington, where one of her sisters was living with her husband and four children.

With the help of her sister's neighbors, Moreno found a job in two days as a clerk in a gardening business, and one week later, she found her own apartment. At her workplace, a friend told her that Boston was nicer than Chehalis and had higher paying jobs. Thus, after three months in the state of Washington, she moved. However, on the way, she stopped in Lockport, Illinois, to visit distant relatives. They warned her about racism in Boston, and so she decided to remain in Lockport. There, she had several jobs. She was as a low-skilled worker, first, in a plastics-manufacturing plant and later, in a box-making factory. Then, she became a delivery driver for a factory making car parts. Her final job, where she spent more than two years, was as a supervisor in a delicatessen at the Marriott Hotel.

While Moreno was living in Lockport, she participated in a group, organized by a Catholic parish, that helps immigrants (mostly Mexicans) learn English and find jobs. She helped other Mexican immigrants fill out job applications, and she helped type the group's paperwork. Moreno's participation in this social activity indicates a high level of integration into the host society, which is one of the characteristics of settled migration (Guarnizo, 1993; Massey et al, 1987).

Although Moreno believed she had moved to the United States permanently, she could not control one important factor: Her two daughters yearned to see their father. Thus, in 1994, four years after moving to the United States, they all flew back to Mexico City for a short trip to visit the children's father. When she tried to renew her tourist visa at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, the consular officers refused, arguing that she could not demonstrate that she had a well paying job in Mexico. The officers, however, did not find her to be a "visa abuser."

Moreno definitely plans to return to the United States. However, she does not want to cross the border as an indocumentada, because it is too dangerous, especially for her children. Since 1994, she has had four low paying jobs, but she has not given up hope of getting a better paying job and qualifying for another tourist visa. She is currently self-employed, earning an average monthly income of US$150 selling instant soups.

Conclusion

Based on the Mexico City survey, I identified four possible migration patterns that MCMA migrants follow: inactive, new or exploratory, temporary, and permanent. The construction of the definitions of these migration patterns required some arbitrary simplifications. However, these patterns represent important methodological instruments to help understand the different strategies pursued by Mexico City migrants.

Socioeconomic conditions in the countries of origin and destination, and the individual characteristics of migrants (such as age, sex, and marital status) define specific migration behaviors. I found that urban experiences that may promote first-time migration include the local economic situation (such as low salaries or a recession), a desire to explore the U.S. labor market, or a thirst for the truth of migrating (a la aventura). Based on this first trip to the United States, new migrants either decide to continue their migratory careers as temporary or permanent migrants, or they simply stop migrating.

Migrants from the MCMA come from numerous barrios and colonias. They migrated individually, and once in the United States, they had little social contact with each other. Because their group ties are so weak, they do not see themselves collectively as a transnational migrant community. Instead, they tend to participate in temporary or permanent migration patterns.

Temporary migrants are individuals who generally retain strong interest in Mexico. In the fieldwork, we found that MCMA temporary migrants do not necessarily aspire to migrate permanently to the United States. On the contrary, they migrate to consolidate their social and economic situation in Mexico. The temporary migration strategy is a common way to quickly obtain money to meet specific expenses: to buy a car, to pay for construction, remodeling or financing of a house, or to start a business. This "fast-cash" strategy also reflects the difficulty, and sometimes the impossibility, that working- and middle-class people face in qualifying for a bank loan in Mexico. Thus, temporary migrants keep their nuclear families in Mexico, and migrate internationally as a strategy to complement their Mexican incomes. The combination of economic activities in Mexico and in the United States through temporary migration reflects not only the existence of social and economic structures that promote this temporary migration system but also the high level of economic integration between these two countries.

The permanent migration system arises from the lack of economic opportunities in Mexico and the availability of year-round, low- and medium-skilled jobs in the U.S. labor market, especially in urban areas. Here individual characteristics also play an important role in migration behavior. Permanent migrants tend to see better opportunities in the United States, not only in terms of wages but also in terms of retirement plans, health services, and, sometimes, education for their children. Permanent migrants tend to settle in the United States with their families, and by providing them with shelter and job networks, they play an important role in helping exploratory or temporary migrants.

Notably, some permanent migrants, particularly those in the 30-39 age group, decided to settle in the United States because they felt that the Mexican labor market favors the incorporation of young people, while the U.S. labor market is less selective with respect to age. This is a good example of how the combination of structural features (such as the discrimination against older workers in Mexico) and individual characteristics of migrants (such as their ages) define a specific migration behavior.

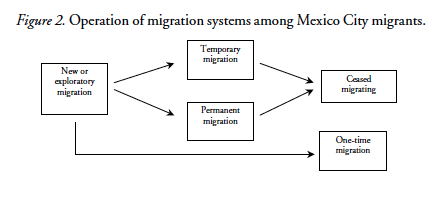

Finally, I argue that the migration systems pursued by MCMA migrants operate simultaneously. These systems feed each other, and they are associated with differences in the migrants' social networks. I argue that new migrants choose either to continue their migratory career (as temporary or permanent migrants) or to stop migrating (see Figure 2).

Those who adopt the temporary migration pattern have the option of pursuing permanent migration or ceasing to migrate altogether.

The permanent migration pattern is fed by new and temporary migrants. Permanent migrants have three possible options: (1) remain in the United States and continue social and economic integration into the host society; (2) reintegrate into the Mexican society by ceasing to migrate, which in the strictest sense represents return migration; and the least likely (3) adopt or return to a temporary pattern. The simultaneous operation of these migration systems takes place at both the individual and household levels. The Mexico City fieldwork indicates that siblings from the same family group followed different migration patterns, and the strategy adopted by one member complemented the strategy adopted by the others. That was the case of Víctor Manuel (see above), who, when he decided to explore the U.S. labor market for the first time as a new migrant, was assisted by his sister and brother who had already migrated permanently migrated to the United States years earlier.

References

Alba, Francisco, "El patrón migratorio entre México y Estados Unidos: su relación con el mercado laboral y el flujo de remesas", in M. García y Griego and G. Vega (eds.), México-Estados Unidos 1984, El Colegio de México, 1985, pp. 201-220. [ Links ]

-----------, "Aspectos urbanos de la migración laboral: La situación en los países de origen", Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 9(3), 1994, pp. 629-656. [ Links ]

Bean, Frank D., T. Espenshade, M. White, and R. Dymowski, "Post-IRCA Changes in the Volume and Composition of Undocumented Migration to the United States: An Assessment Based on Apprehensions Data", in F. Bean, B. Edmonston, and J. Passel (eds.), Undocumented Migration to the United States: IRCA and the Experience of the 1980s, Washington (D. C.), The Urban Institute Press, 1990, pp. 111-158. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población (Conapo), "Encuesta en la Frontera Norte a Trabajadores Indocumentados Devueltos por las Autoridads de los Estados Unidos de América. Diciembre de 1984 (ETIDEU). Resultados Estadísticos", Mexico, D.F., 1986. [ Links ]

Cornelius, Wayne, Labor Migration to the United States: Development Outcomes and Alternatives in Mexican Sending Communities, Final Report to the Commission for the Study of International Migration and Cooperative Development, The Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies/ University of California, San Diego, 1990. [ Links ]

-----------, "From Sojourners to Settlers: The Changing Profile of Mexican Immigration to the United States", in J. Bustamante, C. Reynolds and R. Hinojosa (eds.), U.S.-Mexico Relations: Labor Market Interdependence, Stanford (CA), Stanford University Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Corona Vázquez, Rodolfo, "Modificaciones de las características del flujo migratorio laboral de México a Estados Unidos", in M. A. Castillo, A. Lattes and J. Santibáñez (eds.), Migración y fronteras, El Colef/ALAS/El Colmex, México, 1998. [ Links ]

-----------, Estimación del número de indocumentados a nivel estatal y municipal, Aportes de Investigación No. 8, Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias, UNAM, México, 1987. [ Links ]

Durand, Jorge, Más allá de la línea, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, México, 1994. [ Links ]

Faist, Thomas, "Developing Transnational Social Spaces: The Turkish-German Example", in Ludger Pries (ed.), Migration and Transnational Social Spaces, Ashgate, Aldershot England, 1999, pp. 36-72. [ Links ]

Gamio, Manuel, Mexican Migration to the United States. A Study of Human Migration and Adjustment, Chicago (IL), University of Chicago Press, 1930. [ Links ]

Glick Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Christina Szanton-Blank, "From Immigrants to Transmigrants: Theorizing Transnational Migration", in Ludger Pries (ed.), Migration and Transnational Social Spaces, Ashgate, Aldershot England, 1999, pp. 73-105. [ Links ]

Granovetter, M. S., "The Strength of Weak Ties", American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1973, pp. 134-155. [ Links ]

Guarnizo, Luis E., "Los Dominicanyorks: The Making of a Binational Society", Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 533, 1993, pp. 70-86. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI), ENADID. Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica: Metodología y tabulados, INEGI, Aguascalientes (México), 1994. [ Links ]

-----------, Conteo de Población y Vivienda 1995 (Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Resultados definitivos). Aguascalientes (México), INEGI, 1997. [ Links ]

Kritz, Mary M., and Hania Zlotnik, "Global Interactions: Migration Systems, Processes, and Policies", in Mary M. Kritz, Lin Lean Lim and Hania Zlotnik (eds.), International Migration Systems. A Global Approach, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1992, pp. 1-16. [ Links ]

Legalized Population Survey (LPS), Legalized Population Survey Public Use Tape, matched 1989-1992 file, U.S. Department of Labor-Bureau of International Labor Affairs-Division of Immigration Policy and Research, Washington, D. C., 1996. [ Links ]

Lomnitz, Larissa, "Migration and Networks in Latin America", in A. Portes and H.L. Browning (eds.), Current Perspectives in Latin America Urban Research, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1976, pp. 133-150. [ Links ]

López Castro, Gustavo, La casa dividida: un estudio de caso sobre la migración a Estados Unidos en un pueblo michoacano, El Colegio de Michoacán, México, 1986. [ Links ]

Lozano Ascencio, Fernando, "Continuidad y cambios en la migración temporal entre México y Estados Unidos", in M. A. Castillo, A. Lattes and J. Santibáñez (eds.), Migración y fronteras, pp. 305-320, El Colef/ALAS/El Colmex, México, 1998. [ Links ]

-----------, Bryan Roberts, and Frank D. Bean, "The Interconnectedness of Internal and International Migration: The Case of the United States and Mexico", Soziale Welt, Sonderband 12, 1997, pp. 163-178. [ Links ]

Marcelli, Enrico A., and Wayne A. Cornelius, "The Changing Profile of Mexican Migrants to the United States: New Evidence from California and Mexico", Latin American Research Review, 36(3), 2001, pp. 105-131. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas S., Luin Goldring, and Jorge Durand, "Continuities in Transnational Migration: An Analysis of Nineteen Mexican Communities", American Journal of Sociology, 99, 1994, pp. 1492-1533. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas S., Rafael Alarcón, Jorge Durand, and Humberto González, Return to Aztlan. The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico, University of California Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Mines, Richard, Developing a Community Tradition of Migration: A Field Study in Rural Zacatecas: Mexico and California Settlement Areas, La Jolla (CA), Center for U.S.-Mexico Studies-University of California, San Diego (Monograph Series, No. 3), 1981. [ Links ]

Papail, Jean, "Factores de la migración y redes migratorias", in Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, Migration Between Mexico and United States. Binational Study, vol. 3, 1998, pp. 975-1000. [ Links ]

Pick, James B., and Edgar W. Butler, Mexico Megacity, Boulder, Westview Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro, "Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and Opportunities", International Migration Review, vol. 31, 1997,pp. 799-825. [ Links ]

Roberts, Bryan R., R. Frank, and Fernando Lozano Ascencio, "Transnational Migrant Communities and Mexican Migration to the United States", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 1999, pp. 238-266. [ Links ]

Rouse, Roger, "Making Sense of Settlement: Class Transnationalism, Cultural Struggle and Transformation among Mexican Migrants in the United States", in Nina Glick Schiller, L. Basch, and C. Blank-Szanton (eds.), Towards a Transnational Perspective on Migration: Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Nationalism Reconsidered (Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 645), 1992, pp. 25-52. [ Links ]

Smith, Robert C., "Los ausentes siempre presentes: The Imagining, Making, and Politics of a Transnational Community between Ticuani, Puebla, Mexico and New York City", unpublished dissertation, Political Science, Columbia University, 1995. [ Links ]

Wolcott, Harry F., The Art of Fieldwork, Walnut Creek (CA), Altamira [ Links ]

1 As I mentioned before, I decided to include in this section the Estado de México figures because in most of the surveys (with the exception of the 10% Census sample of 2000) it is not possible to distinguish the municipios that belong to the Mexico City Metropolitan Area (37 in total). However, I recognize that not all international migrants from the Estado de México are part of the mcma, and thus I could be over-estimating this flow.

2 The Central Zone comprises the delegaciones of Coyoacán, Cuauhtémoc, Gustavo A. Madero, Miguel Hidalgo, and Tlalpan. The Periphery Zone comprises three Distrito Federal delegaciones (Iztacalco, Iztapalapa, and Tláhuac) and five state of Mexico municipios (Chimalhuacán, Ecatepec, Los Reyes la Paz, Naucalpan, and Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl).

3 Contrary to what I expected, those who declared were born outside the mcma are equally distributed in the Central and the Periphery zones.

4 The border region comprises Baja California, Baja California, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Sinaloa, Sonora, and Tamaulipas. The historic region comprises Aguascalientes, Colima, Durango, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, San Luis Potosí, and Zacatecas. The south-central region comprises the Distrito Federal, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Estado de México, Morelos, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, Tlaxcala, Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatán (see Corona, 1998).

5 Portes points out that typologies "may become building blocks for theories but, by themselves, they do not amount to a theoretical statement because they simply assert differences without specifying their origins or anticipating their consequences" (Portes, 1997:806).