Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.2 no.2 Tijuana jul./dic. 2003

Artículos

Contemporary Trends in Immigration to the United States: Gender, Labor-Market Incorporation, and Implications for Family Formation

Min Zhou *

* University of California, Los Angeles

Fecha de recepción: 9 de mayo de 2003

Fecha de aceptación: 23 de septiembre de 2003

Abstract

This article provides an overview of contemporary trends in immigration to the United States and a descriptive analysis of gendered patterns of immigrants' economic incorporation. Since the 1970s, both legal and illegal female immigration to the United States has increased steadily, suggesting a trend toward more permanent settlement compared with that of the past. Today, more than half of the immigrants to the United States are female. Although these women often migrate for reasons similar to those of men (such as seeking better economic opportunities or escaping persecution and extreme hardships), their experiences with labor-market incorporation and family formation differ from those of men, raising new issues for the understanding of the role of gender in immigrant settlement and adaptation.

Keywords: international migration, gender, immigrant settlement, labor market, United States.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta una visión general de las tendencias contemporáneas de inmigración a los Estados Unidos, y un análisis descriptivo por género de patrones de la incorporación económica de los inmigrantes. A partir de los setenta, la inmigración femenina legal e ilegal a los Estados Unidos ha aumentado ininterrumpidamente, sugiriendo una tendencia hacia un asentamiento más permanente, comparado con el del pasado. Hoy en día, más de la mitad de los inmigrantes a los Estados Unidos son mujeres. Aunque estas mujeres frecuentemente migran por razones similares a aquellas de los hombres (tales como la búsqueda de mejores oportunidades económicas o escapar de persecución o condiciones extremas), sus experiencias de incorporación al mercado de trabajo y formación familiar son diferentes a las de los hombres, generando nuevas preguntas para entender el papel del género en el asentamiento y adaptación de los inmigrantes.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, género, asentamiento de inmigrantes, mercado de trabajo, Estados Unidos.

General Trends in Contemporary Immigration1

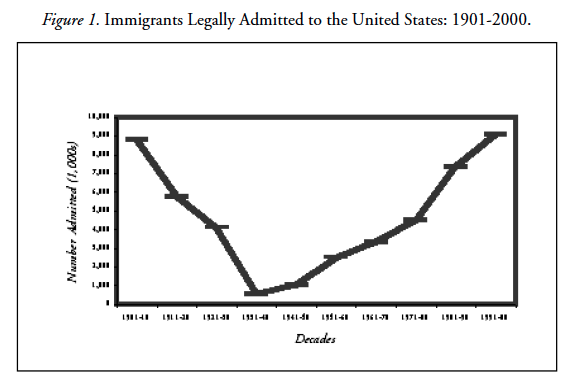

After a long period of restricted immigration, from the mid-1920s to the early 1960s, the United States has once again opened its doors to receive hundreds of thousands of immigrants. According to the U.S. Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (formerly U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service), the country admitted 20.9 million legal immigrants between 1971 and 2000, including 2.2 million formerly unauthorized aliens and 1.3 million special agricultural workers (SAW), who were granted permanent resident status under the provisions of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986. In absolute numbers, contemporary immigration to the United States has exceeded the mass immigration between 1901 and 1930, which reached only 18.7 million (USINS, 2001). Historically, the trend peaked in the first decade of the twentieth century, declined rapidly to its low point in the 1930s, and then picked up speed immediately after World War II, accelerating exponentially since the 1970s (Figure 1). This extraordinary inflow was also accompanied by an increase in the proportion of female immigrants. Between 1991 and 2000, immigration reached its highest level ever—9.1 million legal immigrants admitted, compared with 8.8 million at the previous peak, between 1901 and 1910 (USINS, 2001). Over half were women.

The origins of contemporary immigration have also shifted from being predominantly European to non-European. Immigrants legally admitted into the U.S. before 1961 were mostly from Europe (Figure 2). Beginning in the 1960s, the share of immigrants from Latin America and Asia increased dramatically. In the 1990s, nearly half (47%) of all new arrivals came from Latin America, more than a third from Asia (34%), and only 13% from Europe, compared with more than 90% during the 1900s. During the past two decades, Mexico, the Philippines, China, and India have consistently remained at the top of the list of sending countries. Mexico alone has accounted for more than one-fifth of all legal admissions and has been the number one sending country since the 1960s (USINS, 2001).

In addition to the diversity in origins, contemporary immigration differs from that of the past in other significant ways. First, today's immigration is much more heterogeneous socioeconomically. The image of the poor, uneducated, and unskilled "huddled masses," used to depict the European immigrants at the beginning of the twentieth century, no longer applies to newcomers today, some of whom are highly educated and skilled. For example, more than 60% of Indian immigrants had college degrees, which is ten times the rate for Mexican immigrants and three times that of native-born Americans (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1993). The 2000 Current Population Survey reports that, among immigrant groups, Asians and Europeans had the highest percentages of high school graduates (84% and 81%, respectively) and Central Americans had the lowest (37%), compared with a rate of 87% among native-born Americans. Asians had the lowest poverty rates (13%), whereas Latin Americans and Central Americans had the highest (22% and 24%, respectively), compared with 11% among native-born Americas (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2001a).

Second, contemporary immigration has lower rates of return migration than existed in the past. It was estimated that for every 100 immigrants between 1901 and 1920, 36 returned to their homelands. In contrast, between 1971 and 1990, fewer than a quarter returned (Warren and Kraly, 1985). This trend suggests that contemporary immigrants are more likely to stay in the United States permanently.

Third, contemporary immigration is characterized by a much larger number of undocumented immigrants than the past.2 In 2000, the U.S. Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services estimated that 7 million unauthorized immigrants resided in the United States, up from 5.8 million in 1990. Mexico was the largest source country for undocumented immigration, accounting for 69% of the total, as compared to 58% in 1990 (USINS, 2002). Undocumented migration from Mexico was, in part, due to the U.S. economy's historical reliance on Mexican labor, especially in the agricultural sector, as well as to the operation of migration networks that have facilitated illegal entry through back-door channels (Massey, 1995; Massey et al., 1987). Other source countries that ranked high for size of undocumented immigration to the United States included El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia, Honduras, China, and Ecuador. Nearly one third of undocumented immigrants settled in California and another 15% in Texas; almost half were women (USINS, 2002). Recent U.S. immigration policies, such as IRCA, aimed at curtailing undocumented immigration have led immigrants to settle more permanently. This is especially true for undocumented Mexican migrants, who used to come and go seasonally but who are now unable to do so as easily as in the past, which has turned a transient movement into permanent settlement.

Fourth, refugees and "asylees" (persons granted asylum) are a much more visible component of today's immigration.3 Between 1961 and 1995, annual admission of refugees averaged 68,150, compared to 47,000 between 1945 and 1960, immediately after World War II (USINS, 1997, Table 3). The admission of refugees and asylees today implies the existence of a greatly enlarged base for future immigration through family reunification (Zhou and Bankston, 1998).

Finally, the all-time high level of temporary, nonimmigrant visitors arriving annually in the United States is less publicly noticeable, but it bears a broad implication for potential immigration, both legal and illegal. Official data showed that 22.6 million nonimmigrant visas were issued in 1995—17.6 million (78%) were short-term visitors who came for business or pleasure, and the rest were on long-term, nonimmigrant visas. The latter group included 395,000 foreign students and their immediate families, 243,000 temporary workers or trainees and their immediate families, and a smaller number of traders and investors (USINS, 1997). In 2000, 34.7 million nonimmigrant visas were issued—30.5 million (87.9%) were for temporary visitors, 670,000 (a 70% increase from 1995) were for students and their families, and 673,000 (a 177% increase from 1995) were for temporary workers and trainees and their families (USINS, 2001). These holders of nonimmigrant visas constitute a significant pool of potential immigrants. For example, after completing their studies, students on nonimmigrant visas may apply to the U.S. Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services for permission to pursue practical training, which allows them to seek employment in the United States. That, in turn, increases the probability of their later adjustment to permanent-resident status. Those whose hold temporary work visas sponsored by U.S. employers may be eligible to apply for immigrant visas almost immediately upon arrival. Those who enter as short-term visitors or tourists generally depart on time, but a relatively small proportion, yet a quantitatively large number, of those who might qualify for family-sponsored immigration may overstay their visas and wait in the United States to have their status adjusted. In 1995, almost half of the legal immigrants admitted had their nonimmigrant visas adjusted here in the United States. "Nonimmigrant overstays" accounted for about 40% of all undocumented immigrants (USINS, 1997; 2001).

In sum, socioeconomic diversity, low rate of returned migration, increased numbers of undocumented immigrants and refugees or asylees, and the larger pool of potential immigrants among nonimmigrants reveal the complexity of contemporary immigration. These trends also imply that more than ever before, it is a challenging task to accurately measure the scale and impact of immigration and to manage or control the inflows in contemporary immigrant America (Zhou, 2001).

Mass migration today has reshaped the demographic profile of the U.S. population in some remarkable ways. The 2000 census counted 281.4 million people residing in the United States, 10.4% (or 28.4 million) were foreign born. Among the foreign born, 51% were born in Latin America (34% in Central America including Mexico, 10% in Caribbean, and 7% in South America), 26% were born in Asia, and only 15% were born in Europe (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2001). Since the 1990s, population growth has been uneven among diverse racial groups. While the general population grew by 13% between 1990 and 2000, we have witnessed stagnant growth of non-Hispanic whites (3%), moderate growth of non-Hispanic blacks (21%), and very rapid growth of Hispanics and Asians (61% and 76%, respectively). Some national-origin groups—Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Ecuadorians, Dominicans, Haitians, Jamaicans, Columbians, Chinese Filipinos, Asian Indians, Koreans, Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians—grew at spectacular rates, primarily due to international immigration. As of 2000, members of Central American, Caribbean, and Asian national-origin groups in the United States were predominantly foreign born. In contrast, about one third of Mexican Americans were foreign born (Zhou and Logan, 2003).

Varied rates of population growth and international migration have significantly altered the racial composition of the U.S. population. Non-Hispanic whites now account for 69% of the total U.S. population, down from 76% in 1990, and non-Hispanic blacks account for 12.6%, the same as in 1990. In contrast, Hispanics, having drawn virtually even with non-Hispanic blacks as the nation's largest minority group, now comprise 12.5% of the total U.S. population, up from less than 9% in 1990 (Logan, 2001). The percentage of Asians has remained relatively small, but that group's share of the total population has jumped from 2.8% in 1990 to 4.4% (Logan et al., 2001).

Contemporary immigration is also responsible for uneven geographic distribution of ethnic groups within the United States, particularly Hispanics and Asians. Since 1971, the top five destinations for immigrants have been California, New York, Florida, Texas, and New Jersey. Those states have become the residence of two out of every three newly admitted immigrants. California has been the leading destination since 1976. In contrast, at beginning of the twentieth century, European immigrants were highly concentrated along the Northeastern seaboard and in the Midwest, with the top five destinations being New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. The five most preferred cities were New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Boston (Waldinger and Bozorgmehr, 1996). By 2000, 48% of the immigrants from Asia and 59% of those from Central America lived in the West (mostly in California), and 46% of those from the Caribbean or South America lived in the Northeast (mostly in New York). Almost half of the foreign-born population, compared with only 27% of the native-born American population, lived in central cities rather than suburbs (Logan, 2001; Logan et al., 2001).

The foreign-born population, in general, is much younger than the native-born population. The 2000 Census showed that 79% of the foreign born but only 60% of the native born were in the 18 to 64 age group (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001a). Among new immigrants who were legally admitted to the United States between 1991 and 2000, about two thirds (including 62% of all females) were aged 15 to 44, compared with 44% of the total U.S. population (Table 1). The particularly young age structure of the foreign-born population suggests that these immigrants are active in the economy as well as in human reproduction, childrearing, and other aspects of family life. Immigrant households tend to be larger than average, with 27% of immigrant households in 2000 consisting of five or more people, compared with 13% of native-born households (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001a).

Immigrant Women in the United State: A Profile

Female immigration has become an increasingly prominent feature of contemporary immigration, with women making up more than half of all immigrants legally admitted to the United Sates since 1981 and some 40% to 45% of recent undocumented immigrants. Before 1993, the share of women as a proportion of total immigrants was around 45% to 50%, but since 1993, it was consistently over half (53% to 55%). Some countries of origin account for a disproportionate share of women migrants (Table 2). For example, close to 60% of the immigrants legally admitted to the United States from Mexico, China, the Philippines, and Vietnam were female (USINS, 2001).

Like their male counterparts, today's female immigrants are diverse in their national origins, socioeconomic backgrounds, and patterns of geographic settlement. They also tend to be diverse in types of entry, which include not only family-sponsored but also independent labor migration, and migration as refugees and asylees, as well as undocumented migration. Based on the 1990 U.S. Census,4 a general profile of foreign-born women from selected countries of origin shows that compared with immigrant men, immigrant women were, on average, more numerous, older, less educated, and less likely to be married or participate in the labor market (Table 3). But labor-force participation rate of Jamaican and Filipino women approximated that of immigrant men. In general, immigrant women who were in the labor market were more likely than immigrant men to be concentrated in technical and service occupations.

There were noticeable intergroup differences among immigrant women for every characteristic (Table 3). On average, Mexican women were the youngest of all groups studied, followed by Vietnamese women. Chinese women were the oldest; and the difference in median age between Mexicans and Chinese was 15 years. Indians were most likely to be married, followed by Chinese and Filipinos, whereas Vietnamese were the least likely. In terms of fertility, Indians and Chinese showed the lowest rates in every age cohort whereas Mexicans, by far, had the highest rate in every age cohort, their much younger median age aside. Given the exceptionally young age composition and high fertility among Mexican immigrant women, it is reasonable to predict that issues reated to family formation, such as child birth, child rearing, and the education of the second generation will become especially urgent for this group.

Immigrant women of different origins also showed wide differences in level of educational attainment. Mexicans were overwhelmingly uneducated—three-quarters had not completed high school. Jamaicans were noticeably better educated but were less likely to have attained college degrees. Indians and Filipinos showed exceptionally high levels of educational attainment—more than 68% had at least some college education. Chinese and Vietnamese were bifurcated in educational attainment: Sizeable proportions had not completed high school (44% and 49%, respectively), whereas relatively high proportions had at least some college education (39% and 33%, respectively).

Rates of labor-force participation and unemployment vary among immigrant women of different origins aged 16 and over. Jamaican and Filipino women participated in the labor force at nearly the same rate (over 70%) as immigrant men, and women of other national origins did so at the rate of 50% to 60%. Among those who were in the labor force, twice as many Mexican women as other women were unemployed, whereas Filipinos and Chinese women had much lower unemployment rates. Immigrant women's occupations corresponded somewhat to their educational attainment. Among the most educated groups, such as Filipinos and Indians, the proportions of those in managerial and professional occupations were higher than the average for the American work force. As studies have shown, Mexican immigrant women tend to be employed disproportionately in the domestic services or in the garment industry or other menial factory work; Jamaican and Filipino immigrant women tend to work in the health-care industry, as nurses or nurse aides; Indian women disproportionately tend to be engineers and scientists; Chinese women tend to be either professionals and technicians in the mainstream economy or garment workers and shop-keepers in ethnic economies; and Vietnamese women were fairly evenly distributed across occupations (Fernández-Kelly and García, 1989; Foner, 2001; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994; Ong et al., 1992; Zhou, 1992).

Gendered Patterns of Labor Market Incorporation

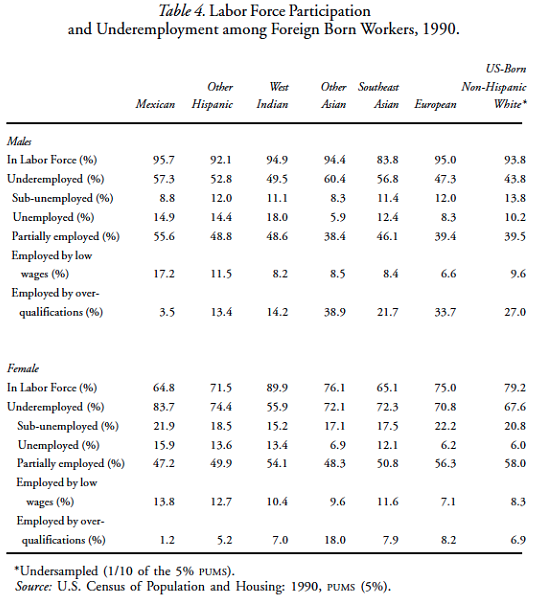

As is well known, immigrants must deal with the issue of economic survival upon arrival in the host country. Contemporary immigrants face not only the disadvantages associated with immigrant status, such as the lack of English proficiency, transferable job skills, and favorable employment networks, but they also face bifurcated labor markets. On one end, "bad" jobs—labor intensive and low paying—are relatively more accessible to immigrants than "good" jobs. This is true because these jobs require either few skills and English proficiency or native-born Americans shun them. But low-skilled jobs do not provide living wages, making it harder to make ends meet, even for two- or multiple-worker families. On the other end of the labor market, "good jobs"—knowledge-intensive and well-paying—are much harder to obtain. Although their availability increases during times of economic prosperity, these jobs still require extensive educational credentials, English proficiency, and the ability to compete with highly skilled, native-born workers. This bifurcated labor-market leaves many immigrants underemployed, working in jobs that pay substandard wages, or employed in occupations for which they are overqualified (Zhou, 2001, and Table 4).

Based on data from the 1990 U.S. Census, analysis of patterns of labor-force incorporation among foreign-born, adult workers between 25 and 64 years of age, reveals that foreign-born male workers of selected origins displayed fairly high rates of labor-force participation, with Mexicans showing the highest rate (96%) and Southeast Asians the lowest (84%) (upper panel of Table 4). The much lower labor-force participation rate for Southeast Asians was due to their status as refugees, most of whom lacked human capital, economic resources, and, because of the absence of preexisting ethnic communities, access to employment networks (Pedraza-Bailey, 1985; Rumbaut, 1995; Zhou and Bankston, 1998). In contrast, Mexicans, who were the most handicapped of all groups under study by their lack of job skills and English proficiency, did not seem to have much trouble getting jobs, thanks to extensive co-ethnic networks (Massey, 1996).

In the highly segmented U.S. labor market, immigrants generally face fewer obstacles in gaining entry, especially into industrial sectors shunned by native-born workers, than they do in moving up occupational ranks. However, they tend to suffer more frequently from various forms of underemployment than do native-born workers. Underemployed workers fall into five main categories:

1) the sub-unemployed, who are currently unemployed but who are too discouraged to continue to look for work;

2) the unemployed, who are currently unemployed but are actively looking for work;

3) the partially employed, who are currently employed part-time or full-time but only during part of the year;

4) those employed full-time, year-round earning low wages; and

5) those employed full-time, year-round in jobs for which they are overqualified.5

All foreign-born men were more likely than native-born, non-Hispanic white men to be underemployed; more than half of all immigrant men, and more than 60% of Asians, experienced some form of underemployment (upper panel, Table 4).

Among underemployed foreign-born men, Mexicans and Asians, were the least sub-unemployed, and Asians were the least unemployed. Partial employment seemed to be the modal category among all underemployed men, including native-born whites. Among immigrant groups, the rates in the "partially employed" category ranged from 38% for Asians through approximately 49% for West Indians and other His-panics, to a high of 56%, registered for Mexican immigrants. When the focus was turned to the next two forms of underemployment—full-time, low-wage earners, and full-time, overqualified workers—significant intergroup differences were quite visible: Mexican men were twice as likely as other immigrant men to earn low wages, but they were the least likely to be overqualified. By contrast, Asians were the most likely of all immigrant men to be overqualified. It is clear that disadvantages in labor-market status do not necessarily affect immigrant groups in the same manner. For those who are not able to obtain adequate employment, Mexicans seem more likely to accept partial or low-wage employment, whereas Asians are more likely to accept the jobs for which they are overqualified.

Patterns of labor-force participation among foreign-born, female workers aged 25 to 64 were quite different from those of foreign-born men. Compared with their male counterparts, foreign-born women were generally less likely to participate in the labor force; when they did, they were more likely to be underemployed. These gender differences were true for every group under study, including native-born whites.

Intergroup differences among women were just as pronounced as those among men. Immigrant women 25 to 64 years of age generally were as likely as native-born, white women to participate in the labor force (lower panel, Table 4). There were exceptions: the labor-force participation rate for West Indian women was 10 percentage points higher than for native-born whites, whereas Mexicans and Southeast Asians were 14 percentage points lower. Among those who were in the labor force, most were underemployed, regardless of origins, but West Indian women had the lowest underemployment rate, lower even than native-born white women.

Among underemployed women, perhaps most noticeable were the very high rates of sub-unemployment for all groups, including native-born, non-Hispanic whites. Although we can assume that sub-unemployed men are discouraged workers who have detached themselves from the labor market involuntarily, the same assumption may not be applicable to sub-unemployed women, who may voluntarily withdraw from the labor force for natural life-course reasons, such as marriage and child-bearing. Similarly, partial employment among men may be viewed as an imposed disadvantage, but partial employment among women may be considered a collective strategy to supplement men's underpaid wages in order to meet the basic needs of the family. Among immigrant women who were in the labor force, Mexicans, other Hispanics, West Indians, and Southeast Asians were disproportionately unemployed whereas Asians were occupationally overqualified.

Implications for Family Formation

Research on international migration neglected immigrant women until the late 1970s (Pessar, 1999). This article's descriptive analysis highlights that more than half of the immigrants to the United States in recent years are female and that this trend is likely to continue given the priority for family reunification in current U.S. immigration policy as well as global economic and geopolitical forces that stimulate both highly skilled and low skilled women to migrate independently. Many women migrate for the same reasons as men, such as seeking better opportunities or escaping persecution. Whereas many arrived in the United States with, or to join, their families, others were sponsored by prospective employers, and still others migrated independently. Some made the move voluntarily with adequate preparation, whereas others were pushed out and resettled here reluctantly and abruptly, and still others came illegally, enduring enormous hardships in their journey to the United States as well as on arrival here.

In the past, international migration was dominated by male sojourn-ers. The "women's side" often resided in the country of origin (Engel, 1986; Pedraza, 1991). Today, the arrival of immigrant women in large numbers raises new issues for family formation, settlement, and adaptation that should be examined through a gender-sensitive lens. These issues entail several important implications.

First, female migration implies a more gender-balanced mode of permanent settlement in the host society than does male migration, in which sojourning and relayed migration are highly visible. In the past, although some men migrated with their wives and children, most did so alone. They came as sojourners, with the intention of finding work for a certain length of time and then returning to the homeland. While in the United States, they regularly sent remittances to support their families left behind. Also common was relayed migration, in which a man came first and, later, sent for his family or briefly returned home to find a wife whom he could bring to the United States. Even though some women migrated independently, they were largely overshadowed by those who arrived as spouses or dependents.

Sojourning and relayed migration created unconventional types of living arrangements, such as bachelor societies or split households, where husbands and wives lived in two different countries, which resulted in the reaffirmation of men's power in the family (Glenn, 1983; Zhou, 1992). Today, when women migrate at a rate equal to or higher than that of men, settlement becomes more a family than an individual issue. However, men no longer enjoy the kind of power they had either when living in split households (in which family members depended on the man's remittances) or participating in relayed migration (in which a man's sponsorship and role in getting the family settled were clearly acknowledged by the family members who benefited). Instead, because men and women arrive simultaneously and face similar obstacles, both must work together and share the responsibility for family settlement.

Second, as gendered migration reshapes settlement, it also redefines gender roles in family economics. Although women, native-born and foreign-born alike, have entered the labor force in increasing numbers, immigrant women have less choice about whether they should work or not and what kind of work they should pursue. This is mainly because of the additional disadvantages of foreign-born status, such as lack of access to certain public resources and welfare benefits (or lack of information needed to access resources to which they are entitled), and because of the relatively low social status of their spouses, most of whom are also immigrants.

As we have seen, immigrant men are disproportionately underemployed compared to native-born Americans. This suggests that their work is insufficient to ensure for the family's survival. Thus, immigrant women's contribution of paid work is probably motivated more by the need to provide for the family's survival than out of a desire to achieve or maintain a certain standard of living. More specifically, the participation of immigrant women in paid work is a response to the structural disadvantages that immigrant men experience in the U.S. economy. When men are unable to serve as sole or primary breadwinners, women must fill in by working. In many immigrant families, women's economic contribution is a matter of putting food on the table rather than having better food. Thus, women's work is not simply secondary but equal to that of men. Because of the urgency to meet basic needs required to survive, many immigrant women enter the labor market not for individual gratification or self-actualization but to improve the family's economic well-being and in an attempt to ensure its eventual upward social mobility (Pérez, 1986; Pedraza, 1991; Zhou, 1992).

Third, migration to the United States has brought immigrant women new opportunities and intangible benefits, such as individual freedom and economic independence, which for some may have been unimaginable in their countries of origin. Simultaneously, however, immigration to the United States creates new challenges for these women. Immigrant women's changing economic role affects family relations in some distinctive ways. Research shows that working women of all backgrounds tend consciously to develop cooperative roles vis-à-vis their husbands or male family members, such as sharing responsibilities for decision-making and family activities. However, men, regardless of country of origin, tend to react to the change slowly and sometimes reluctantly. Since men continue to consider themselves to be the primary breadwinners, a view that is reinforced by tradition, they are unwilling to share women's domestic responsibilities even as women take up paid work. Thus, the seemingly progressive experience for women often turns out to be a burden, or "employment without liberation," which in turn can lead to strained marital relations and even family dissolution (Ferree, 1979; Hochschild, 2003).

However, this gender dynamics is manifested differently, though quite subtly, in the immigrant family. Many immigrant men experience the loss of social status outside the home, and thus, in the private domain, they tend to hold onto traditional values and patriarchal traditions as a way to compensate. Moreover, since immigrant men and women, in comparison to the native-born counterparts, tend to be more interdependent on each other for their survival, they are thus less likely to choose divorce as the ultimate means of resolving conflicts. In fact, many immigrant women have to stretch, rather than challenge, their traditional gender role in order to include paid work as part of that role (Pedraza, 1996). As a result, they are constantly caught in conflictual obligations as they struggle to fulfill a triple role as wives, mothers, and wage earners in ways that will not upset family stability (Kibria, 1993).

Fourth, like their male counterparts, immigrant women lack useful connections to social-support networks and to mainstream institutions due to the structural constraints to which all immigrants are subject, such as poor English proficiency, unfamiliarity with the host society, and social isolation. They are, nonetheless, primarily responsible for rebuilding social networks for their families within the ethnic community. Additionally, they must navigate their way through the larger society's maze of public and private institutions related to employment, social welfare, and education. On top of that, they must manage everyday household affairs, including raising children and caring for the elders. It is interesting to note that because of the multiple roles that immigrant women play, many of the newly built networks and social contacts become women-centered, which, in turn, gives women greater leverage and more room in negotiating power in the family (Kibria, 1993).

Finally, like their male counterparts, immigrant women have maintained intrinsic links to their countries of origins. Once settled in the United States, many must support their families back home by sending remittances on a regular basis, which dilutes the limited resources available to enable them to get established and be upwardly mobile in the host society. They themselves may become future sponsors for migrating family members, creating a key link in the chain of family migration.

In summary, the trend of female migration to the United States in the twenty-first century is expected to increase steadily over time as more and more immigrants migrate with families and settle permanently. As immigrant women have become increasingly visible in the family, the community, and the workplace, they have reshaped the gendered processes of settlement and family formation. They have also redefined gendered roles in ways that may not necessarily challenge the patriarchal tradition, since they must simultaneously play a triple role, as wives, mothers, and wage earners.

References

Clogg, Clifford C., Scott R. Eliason, and R. Wahl, "Labor-Market Experiences and Labor-Force Outcomes: A Comprehensive Framework for Analyzing Labor-Force Dynamics", American Journal of Sociology, 95, 1990, pp. 1536-76. [ Links ]

Engel, B. A., "The Women's Side: Male Outmigration and the Family Economy in Kostroma Province", Slavic Review, 45, 1986, pp. 257-71. [ Links ]

Fernández-Kelly, M. Patricia, and Ana García. "Informalization at the Core: Hispanic Women, Homework, and the Advanced Capitalist State", in Alejandro Portes, Manuel Castells, and Lauren Benton (eds.), The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989, pp. 247-64. [ Links ]

Ferree, M. M., "Employment without Liberation: Cuban Women in the United States", Social Science Quarterly, 60, 1979, pp. 35-50. [ Links ]

Foner, Nancy (ed.), New Immigrants in New York, 2d edition, New York, Columbia University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Glenn, Evelyn, "Split Household, Small Producer, and Dual Wage Earner: An Analysis of Chinese-American Family Strategies", Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 1983, pp. 35-46. [ Links ]

Hochschild, Arlie Russell, The Second Shift, New York, Penguin, 2003. [ Links ]

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette, Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences of Immigration, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Houser, Philip M., "The Measure of Labor Utilization", Malayan Economic Review, 19, 1974, pp. 1-17. [ Links ]

Kibria, Nazli, Family Tightrope: The Changing Lives of Vietnamese Americans, Princeton, University of Princeton Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Logan, John R., "The New Latinos: Who They Are, Where They Are", Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research-State University of New York at Albany, September 10, 2001. Available at http://mumford1.dyndns.org/cen2000/report.html. Accessed on November 18, 2003. [ Links ]

----------, with Jacob Stowell and Elena Vesselinov, "From Many Shores:Asians in Census 2000", a report by the Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research-State University of New York at Albany. Available at http://mumford1.dyndns.org/cen2000/report.html, November 19, 2001. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas S., "The New Immigration and Ethnicity in the United States", Population and Development Review, 21(3), 1995, pp. 631-52. [ Links ]

----------, "The Age of Extremes: Concentrated Affluence and Poverty in the Twenty-First Century", Demography, 33(4), 1996, pp. 395-412. [ Links ]

----------, Rafael Alarcón, Jorge Durand, and Humberto González, Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Ong, Paul M., Lucie Cheng, and Leslie Evans, "Migration of Highly Educated Asians and Global Dynamics", Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 5(1), 1992, pp. 1-19. [ Links ]

Pedraza, Silvia, "Women and Migration: The Social Consequences of Gender", Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 1991, pp. 303-25. [ Links ]

----------, "Cuban Refugees: Manifold Migrations", in Silvia Pedraza and Rubén G. Rumbaut (eds.), Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race and Ethnicity in America, Belmont (CA), Wadsworth, 1996, pp. 263-79. [ Links ]

Pedraza-Bailey, Silvia, Political and Economic Migrants in America: Cubans and Mexicans, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Pérez, Lisandro, "Immigrant Economic Adjustment and Family Organization: The Cuban Success Story Reexamined", International Migration Review, 20, 1986, pp. 4-20. [ Links ]

Pessar, Patricia R., "The Role of Gender, Households, and Social Network in the Migration Process: A Review and Appraisal", in Charles Hirschman, Philip Kasinitz, and Josh DeWind (eds.), The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience, New York, Russell Sage Foundation Press, 1999, pp. 53-70. [ Links ]

Rumbaut, Rubén G., "Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian Americans", in Pyung Gap Min (ed.), Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 1995, pp. 232-70. [ Links ]

Sullivan, Theresa A., Marginal Workers, Marginal Jobs: Underutilization in the U.S. Work Force, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1978. [ Links ]

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1990 Census of the Population: The Foreign-Born Population in the United States, Washington (D.C.), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993. [ Links ]

----------, Profile of the Foreign Born Population in the United States, 2000,Current Population Reports, Special Studies, Series P23-206. Washington D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/p23-206.pdf. Internet release in December, 2001a. [ Links ]

----------,"Population by Sex and Age for the United States, 2000", http://www.factfinder.census.gov/servlet/QTTable?geo_id=01000US&ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&qr_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_QTP1&_lang =en&_sse=on. Internet release on April 2, 2001b. [ Links ]

U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (USINS), Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1995, Washington (D.C.), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997. [ Links ]

----------, Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 2000, Washington (D.C.), U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001. [ Links ]

----------, "Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: 1990-2000", Washington (D.C.), Office of Policy and Planning of the USINS, 2002. [ Links ]

Waldinger, Roger, and Mehdi Bozorgmehr, "The Making of a Multicultural Metropolis", in Roger Waldinger and Mehdi Bozorgmehr (eds.), Ethnic Los Angeles, New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1996, pp. 3-37. [ Links ]

Warren, Robert, and Ellen Percy Kraly, The Elusive Exodus: Emigration from the United States, Population Trends and Public Policy Occasional Paper #8 (March), Washington (D.C.), Population Reference Bureau, 1985. [ Links ]

Zhou, Min, Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave, Philadelphia (PA), Temple University Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Zhou, Min, "Contemporary Immigration and the Dynamics of Race and Ethnicity", in Neil Smelser, William Julius Wilson, and Faith Mitchell (eds.), America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences, vol. I, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council, Washington (D.C.), National Academy Press, 2001, pp. 198-240. [ Links ]

----------, "Contemporary Female Immigration to the United States: A Demographic Profile", in Philippa Strum and Danielle Tarantolo (eds.), Women Migrants in the United States, Washington (D.C.), Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and Migration Policy Institute, 2003, pp. 23-34. [ Links ]

----------, and Carl L. Bankston III, Growing up American: The Adaptation of Vietnamese Adolescents in the United States, New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1998. [ Links ]

Zhou, Min, and John R. Logan, "Increasing Diversity and Persistent Segregation: Challenges for Educating Minority and Immigrant Children in Urban America", in Stephen J. Caldas and Carl L. Bankston (eds.), The End of Desegregation, Hauppauge (N.Y.), Nova Science Publishers, 2003, pp. 177-94. [ Links ]

1 Some material in this article was drawn from previously published work (Zhou, 2001 and 2003). I thank Chiaki Inutake for her research assistance.

2 When making this comparison, one should bear in mind that earlier European immigrants were less susceptible to being labeled as "undocumented" because until 1924, few laws restricted their entry.

3 A refugee or an asylee can be anyone with a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, membership in a social group, political opinion, or national origin. Refugees seek protection while still outside the United States, whereas asylees seek protection once in the United States.

4 Comparable data from the 2000 Census are not yet available.

5 Modified from the Labor Utilization Framework (LUF) developed by Houser (1974), Sullivan (1978), and Clogg et al. (1990).