Introduction

Hyperglycemia is a well-known poor prognostic factor associated with adverse outcomes in neurocritical conditions such as ischemic stroke, even in the absence of known diabetes mellitus. However, its contribution as an independent predictor in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) is limite1,2.

High blood glucose concentration can be present in one-third of patients with aSAH at any given time during hospitalization3-6. Retrospective studies have shown that for every mg increase in glucose over 140 mg/dL, there is an increase in mortality and adverse outcome7. In the present study, we aim to analyze the relationship between blood glucose level at admission and in-hospital mortality risk in patients with aSAH.

Materials and methods

Data were obtained from the prospective hospital-based national multicenter RENAMEVASC registry (Registro Nacional de Enfermedad Cerebral Vascular) study where consecutive patients with all stroke types (ischemic and hemorrhagic) were registered over a 2-year period in 25 tertiary referral centers across the country. A total of 2000 patients were studied8,9. For the present analysis, only patients with a diagnosis of aSAH confirmed by 4-vessel angiography were included.

Demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors, clinical presentation at hospital admission (Glasgow Coma Scale and Hunt and Hess scale), radiological characteristics (aneurysm topography by angiography and Fisher score), medical and neurosurgical treatment, in-hospital complications, and final outcome at hospital discharge were also obtained from the original registry8,9.

Blood glucose was measured at hospital admission (using the first blood sample before any intervention) and patients were categorized into two groups depending on blood levels: ≤ 150 mg/ml (≤ 8.3 mmol/l) and > 150 mg/ml (> 8.3 mmol/l). The primary outcome was the association of admission blood glycemia with in-hospital mortality. We used the prognostic Hunt-Hess scale, which classifies patients regarding their clinical features using a numbered scale (I to V, asymptomatic to comatose, respectively) and the Fisher scale which uses computed tomography scan findings to classify patients (I to IV, no visible blood in imaging study, diffuse or no subarachnoid blood with intracerebral or intraventricular hematoma, respectively) to predict the risk of developing vasospasm as a basis to determine prognosis. Lower scores on the Hunt-Hess and the Fisher scales indicate better prognosis. The study was approved by the ethical committee of every participating center in the study, cataloged as a no risk study with no intervention. Patient information was obtained under previous authorization by written consent in all cases.

Statistical analysis

We grouped patients using quartiles with the following variables: Hunt-Hess scale, Fisher scale, Glasgow Coma Scale, and admission glycemia. Multivariable analyses were modeled to find independent predictors of in-hospital mortality, with adjustment for relevant confounders. All cases were evaluated by a neurologist using the Hunt and Hess score for aSAH to determine the mortality risk associated with the severity of the hemorrhage on imaging studies and their relation with other individual mortality predictors (including glycemia).

Results

In the original registry, a total of 231 patients (153 [66%] women and 78 [34%] men) were included for analysis. Mean age was 51.8 years (median 51 years, range 16-90). A total of 42% of patients had a prior diagnosis of hypertension and 7% had a history of diabetes mellitus. History of tobacco use was a present in 35% of patients. Median duration of hospital stay was 23 days (range 2-98). In-hospital mortality occurred in 20% of cases; 54% were due to a neurological cause, 28% due to a systemic condition (including infection, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and cardiac arrhythmia), and 17% with both.

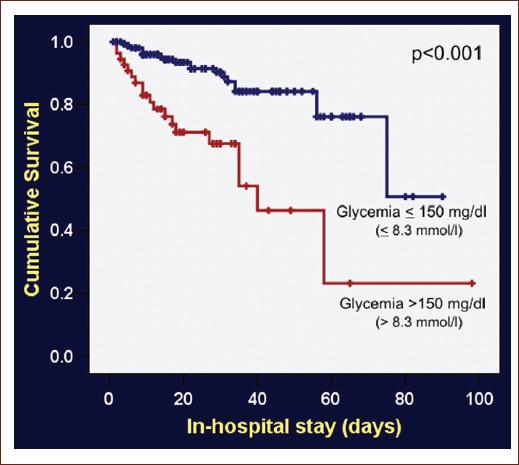

Of the total o patients, only 219 have a blood glucose test prior any intervention. A total of 55 (25%) patients had a blood glucose level in the upper quartile (> 8.3 mmol/l or > 150 mg/dL) compared with 164 patients (75%) with lower glucose level. Mortality occurred in 50% among patients with hyperglycemia. Higher grades in the Hunt-Hess scale (Grades III-V) and Fisher scale (III-IV) were related to a higher mortality rate (60% and 100%, respectively) in comparison with lower grades. A lower score in the Glasgow scale was not related to mortality rate. These subanalyses are shown in table 1. Survival analyses and Kaplan–Meier curves showed a higher probability of in-hospital death with admittance blood glucose level in the higher quartile of the sample (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). After a binary logistic regression model controlled for clinical and laboratory variables identified at hospital presentation, predictors of in-hospital mortality were Hunt-Hess score > 2 (odds ratio [OR]: 3.79, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.43-10.06) and glycemia in the higher quartile of the sample (OR: 2.98, 95% CI: 1.12-7.96) (Table 2).

Table 1 In-hospital mortality based on clinical characteristics and cerebral imaging at hospital admission

| Variable | Total | Gender | p value | Age (years) | p value | Intrahospital death | p value | Multivariate p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ≤ 49 | ≥ 50 | Present | Absent | ||||||

| Hunt-Hess scale | |||||||||||

| Grade I-II, n (%) | 133(66) | 51(74) | 82(62) | 0.09 | 72(73) | 61(59) | 0.04 | 14(40) | 119(71) | < 0.001 | 0.046 |

| Grade III-V, n (%) | 69 (34) | 51 (38) | 18 (26) | 26 (27) | 43 (41) | 21 (60) | 48 (29) | ||||

| Fisher scale | 0.86 | 0.34 | < 0.001 | 0.997 | |||||||

| Grade I-II, n (%) | 52 (26) | 17 (25) | 35 (26) | 28 (29) | 24 (23) | 0 (0) | 52 (31) | ||||

| Grade III-IV, n (%) | 149 (74) | 52 (75) | 97 (74) | 68 (71) | 81 (77) | 34 (100) | 115 (69) | ||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 0.007 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | 0.026 | |||||||

| 13-15, n (%) | 149 (67) | 61 (80) | 88 (59) | 78 (76) | 71 (59) | 17 (39) | 132 (73) | ||||

| 9-12, n (%) | 43 (19) | 9 (12) | 34 (23) | 12 (11) | 31 (25) | 14 (33) | 29 (16) | ||||

| 3-8, n (%) | 32 (14) | 6 (8) | 26 (18) | 13 (13) | 19 (16) | 12 (28) | 20 (11) | ||||

| Admission glycemia | 0.70 | 0.056 | < 0.001 | 0.026 | |||||||

| ≤ 150 mg/dl, n (%) | 164 (75) | 55 (73) | 109 (76) | 84 (43) | 65 (46) | 20 (50) | 144 (80) | ||||

| > 150 mg/dl, n (%) | 55 (25) | 20 (27) | 35 (24) | 20 (57) | 35 (54) | 20 (50) | 35 (20) | ||||

aSAH: aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier cumulative survival curves in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage with or without hyperglycemia.

Table 2 Multivariate analysis on factors predicting in-hospital mortality after aSAH: binary logistic regression model

| Variable | Multivariate odds ratios (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Glycemia > 8.3 mmol/l ( > 150 mg/dl) | 2.98 (1.12-7.96) | 0.03 |

| Hunt-Hess > 2 | 3.80 (1.43-10.06) | 0.007 |

aSAH: aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

Hyperglycemia as a poor prognosis variable in patients with aSAH was first mentioned in 192510. Since then, it has been related to non-neurological systemic complications, delayed vasospasm, cerebral infarction, prolonged in-hospital stay, poor functional outcome, and death. Admittance and perioperative blood glucose have been associated with a poor prognosis after aSAH11. Despite this early observation, the relationship has been scarcely investigated in other studies (Table S1). Hyperglycemia represents the metabolic response to stress12-14 and is associated with a higher risk of vasospasm and secondary ischemia15,16. It is difficult to determine if hyperglycemia is the cause, the consequence or an epiphenomenon related to medical complications such as pneumonia. Therefore, admittance blood glucose concentration (before several metabolic and medical complications occur) could better define the role that hyperglycemia plays in the outcome of patients with SAH, particularly in those with ruptured aneurysms, after controlling for several factors known to affect the outcome in this condition.

Supplementary material AAlthough in-hospital hyperglycemia has been accepted as a well-characterized contributing poor prognostic and death predictor in the neurosurgical critically ill patients, the role of admission glucose levels is not well described in aSAH, remaining poorly characterized in multivariate models of representative population samples13,17-19.

The relationship between hyperglycemia and poor outcomes has been well described in ischemic stroke and is associated with infarct expansion, worse functional outcome, increased length of hospital stay, and death19-21. Multiple pathophysiological pathways including vascular inflammatory reactions and free radical production lead to cell death and loss of viable brain tissue after stroke22-24. Vasospasm, one of the most feared complications in aSAH related to delayed ischemia and infarction, is present in up to 20% of patients25,26.

Recent studies have demonstrated that elevated blood glucose causes dysregulation of certain enzymes including endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase and induced NO synthase. The resulting endothelial damage promotes NO depletion and contributes to secondary vasospasm27. Despite several studies describing the occurrence of hyperglycemia and negative outcomes in aSAH, the association of admission glucose with in-hospital mortality has not been described yet. Our study is the first of its kind in Mexican population to test this hypothesis2-5,7,12,14-20,24,25,28-31.

In our study, we found that the blood glucose levels at admission yield important information on mortality and prognosis. There are several useful scores available that include clinical and radiological information (Hunt-Hess score and Fisher score) which are routinely used as a prognostic tool, but none of them include admission glucose levels. Glucose testing is cheap, readily available, and routinely performed in all centers. Based on these results and the available literature, hyperglycemia should be one of the most critical management targets in patients with aSAH. Regarding the actual evidence, glucose control might help prevent vasospasm and subsequently brain infarct and other in-hospital complications that contribute to the currently poor outcome of this disease32. Early detection and management of hyperglycemia in patients with aSAH should be a primary target in the management of these patients in an effort to improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Hyperglycemia is an important independent risk factor associated with in-hospital mortality and adverse prognosis after aSAH. More prospective controlled studies are required to support these results and determine how glucose control might affect mortality and functional prognosis in patients with aSAH. The main limitation of this study is the lack of control of confounding factors as the diabetes mellitus disease control status and medication in patients with this diagnosis.

Supplementary data

A systematic review of studies about the association between glycemia and SAH is include in Table S1.

Supplementary data are available at Revista Mexicana de Neurociencia online (www.revmexneurociencia.com/index.php). These data are provided by the corresponding author and published online for the benefit of the reader. The contents of supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)