INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a heterogeneous disease in terms of etiology, clinical presentation, and disease management. The major risk factor for HCC in western countries is cirrhosis related to chronic hepatitis C.1 - 3 In most centers, clinical treatment is guided by BCLC staging.4

Sorafenib is a multi-kinase inhibitor, of oral administration, with antiproliferative and antiangiogenic activity,5 and it is the first targeted agent to lead to better outcomes in patients with advanced-stage HCC (BCLC-C)6 with large or multifocal tumors associated with vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread and mild cancer-related symptoms. In the pivotal trial SHARP, Llovet, et al.6 reported an increase in overall survival (OS) of more than 30% in BCLL-C patients treated with sorafenib compared to those who received the placebo. In the same study, sorafenib treatment was, generally, well tolerated with mild toxicity and with manageable adverse events. The SHARP subgroup analysis7 showed that the safety profile of sorafenib appeared to be similar irrespective of Child-Pugh status, BCLC stage and initial sorafenib dose. However, the prognosis for patients with advanced stage of HCC remains poor, with a median OS rate of 5.5-15months. 6 , 8 - 10

Recently, the BCLC classification has been refined in terms of treatment indications;11 patients who are not candidates for the first-line therapy for their stage can be migrated to the treatment option for the next BCLC stage (treatment stage migration concept).12 Thus, some patients with earlier evolutionary stages (BCLC-B) who demonstrate disease progression after second transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), have poor tolerance to TACE or in whom the procedure is technically difficult may be treated with sorafenib.13

The most common AEs associated with sorafenib treatment include dermatologic toxicities, diarrhea, fatigue and hypertension.6 , 9 , 14 Some AEs have been described as clinical parameters predictive of higher tumor response to sorafenib15 and better overall survival in previous retrospective analyses.16 , 17 Furthermore, the intensity of the AEs to sorafenib was also associated with longer survival in a recent prospective study.18

A prospective study9 evaluating HCC prognostic factors for survival in patients treated with sorafenib has demonstrated that the presence of dermatologic AEs during the first 60 days of treatment (DAE60) is a reliable clinical factor predicting better survival and may constitute an early indicator of anti-tumor activity.

The aim of the present retrospective study was to determine if DAE60 and other frequently and early seen AE had an impact on survival of patients treated in our cohort and to determine if the findings observed in the prospective study9 were valid in our population.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Information with respect to sorafenib treated patients in two hepatology reference centers in Brazil (Irmandade Santa Casa de Porto Alegre and Instituto do Cancer do Estado de São Paulo ICESP) was collected and included in a database. The decision to treat patients with sorafenib was been made under real-life practice conditions. Demographic data, liver disease, tumor characteristics, duration of therapy, AEs, and survival information were also collected. Patients were initiated on sorafenib and kept at the full recommended dose (800 mg/day) until progression (radiological or symptomatic) or unacceptable toxicities. Discontinuing sorafenib in the presence of radiological progression was necessary because in some Brazilian states, Sorafenib costs are no longer covered through the public health system for patients with this type of progression during therapy, even in the absence of symptomatic progression, making the availability of the drug very difficult for these patients.

Radiological progression was defined according to mRECIST criteria19 and symptomatic progression was defined as the development of liver decompensation or worsening performance status.

DAE60 was defined as the development of a dermatological reaction such as hand-foot reaction, rash, edema, erythema and foliculitis of any grade within the first 60 days of treatment with sorafenib.

Performance status (PS) was recorded using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale.

Patients and data collection

This retrospective study included all patients referred to the Hepatology Center of Santa Casa de Porto Alegre and ICESP between June 2010 and July 2014 who received at least one dose of sorafenib and underwent at least one follow-up assessment. Patients were diagnosed histologically or radiographically according to AASLD guidelines4 with advanced HCC. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of starting sorafenib until the date of death or end of follow-up. Data were collected using case report forms. AEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0. All AEs (any type of AE) occurring within the first 60 days of sorafenib treatment and recorded on the patients' medical charts were collected and briefly described in the results section. However, only the two most frequent AEs (dermatologic reactions and diahrrea) were considered in the survival analysis

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Irmandade Santa Casa de Porto Alegre and by the local ethic committees.

Statistical analysis

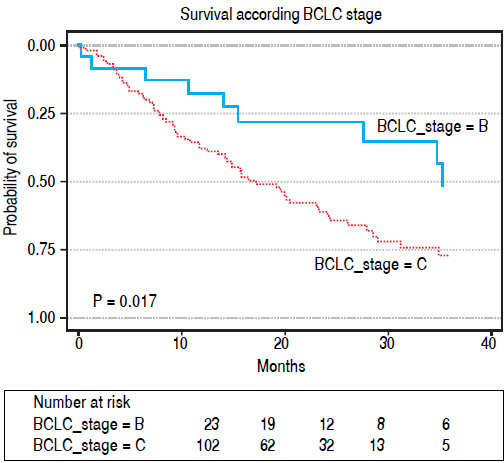

Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation when normally distributed and median and interquartile range when not. Normality was verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Patient survival was assessed by Kaplan-Meier curves and comparisons between groups by the Log-Rank test. The significance level was 5%. Variables with a p-value less than 0.10 in the univariate analysis and other clinical relevant variables were entered in Cox proportional hazard regression models using both backwards and forward stepwise selection. Wald test was used to test statistical significance. The variables included in the final Cox model were as following: BCLC classification, performance status (0 vs. 1 and 2), vascular invasion or metastasis, diarrhea AE and dermatologic AE. Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY); and survival curves (Figures 1 and 2) were performed using STATA Statistical Software, version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of the 134 patients meeting the study criteria, 7 were excluded due to lack of data for analysis or uncorrectable errors in data collection, and 127 were included in the study.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients are shown in table 1. Cirrhosis was present in 94.5% of patients and the most frequent etiology of cirrhosis was HCV (70.9%). The baseline level of alpha-fetoprotein was < 200 ng/mL in 56.6%.

Table1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients.

CV: HCV: hepatitis C virus. HBV: hepatitis B virus. PS: performance status. BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification. PT: prothrombin time.

The majority of patients (85.6%) had Child-Pugh A cirrhosis and were asymptomatic (PS-0 in 63%). In the BCLC classification, 102 (80.3%) patients had tumor in stage C and 23 (18.1%) were BCLC-B.

More than half of the patients (n = 67, 52.8%) received sorafenib after failure to some local treatment including TACE in 73.1%, 16.4% surgery, 6% radiofrequency ablation and 4.5% percutaneous ethanol injection. Only 5 (8.3%) BCLC-B patients received sorafenib as first-line treatment. There was some variation in prior treatment across Child-Pugh subgroups, with a greater proportion of ChildPugh A patients having received prior locoregional therapy compared with Child-Pugh B (57.4% vs. 33%).

The cause of treatment migration to sorafenib was: untreatable progression with vascular invasion in 31.1%, extrahepatic spread in 23%, tumoral progression with large multifocal HCC involving both lobes in 20.6%, tumor irrigation unfavorable to further TACEs in 6.3%; TACE-related serious AEs in 4.8% and partial response to second TACE in 1.6% of the patients.

The presence of vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread correlated with worsening PS, with more patients with PS1-2 than PS0 when extrahepatic disease was present (p = 0.02).

Treatment, adverse events and dose modification

The median duration of treatment was 10 months (range: 0.1-47 months) and 59.1% of the treated patients needed at least one dose modification. With the exception of three patients, all others presented at least one AE to sorafenib. The most common adverse event in the first 60 days of treatment were diarrhea (62.2%) and dermatological reaction (42%) of which: hand-foot syndrome in 35.4%, rash in 5.2% and mucositis in 1.4%, asthenia (31.5%); hyporexia (24.4%) and weight loss (20.5%).

A total of 83 different kinds of AEs were observed. The maximum degree of AEs was grade 1 in 12% of patients, grade 2 in 46.4%, grade 3 in 28.8% and grade 4 in 12.8%. The AEs were not significantly different according to BCLC B or C staging, Child-Pugh A or B score or performance status 0 or 1-2.

The main reasons for discontinuation of sorafenib treatment were: radiological tumor progression (45%), symptomatic progression (30.6%), patient choice(7.2%), gastrointestinal bleeding (5.4%), acute myocardial infarction (2.7%),and ischemic cerebrovascular accident (1.8%).

Seventy-nine (62.2%) patients died and the most frequent causes of death were: tumor progression with liver failure in 44.8%, infection in 11.5%, digestive hemorrhage in 6.4% and tumor rupture in 2.6%.Of the patients who were still alive at last follow-up,18 (14.2%) were still taking Sorafenib.

Overall Survival

Median OS was 19.9 months (range: 0.1-47 months) (percentiles 25th75th, P25-75: 8-40 months). OS was 64.6% (95%CI: 55.9%-73.2%) at 1 year and 26.6% (95%CI: 16.6% -36.6%) at 3 years (Figure 1).

Median survival was significantly higher in BCLC B patients (n = 23) 35 months (P25-75: no events 15 months), compared to BCLC C (n = 102) 17 months (P25-75: 35-8 months) (p = 0.017), as show in Figure 1. The median survival rate was higher in patients with PS-0, 24 months (P25-75%: 47-11 months). Than patients with PS1-2, 12.5 months (P25-75: 35-6 months), however the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.059). Median OS of the Child A patients (26.6 months) vs. Child B (19.8 months; p = 0.137) was also not significantly different.

The presence of diarrhea within the 60 days of treatment with sorafenib was associated with an increased survival in the univariate analysis: median OS 23.3 months (CI 95% 15.2 - 31.5 months) in patients who experienced diahrrea and 12.5 months(CI 95% 8.8-16.2 months) in those who did not experienced the event (p = 0.031). However, this event was not confirmed as a prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis adjusted by other relevant variables, including DAE60.

On the other hand, the presence of DAE60 was significantly associated with improved median OS, 31 months (P25-75: 48-16 months) compared to patients who did not have this adverse event, 14 months (P25-75: 24-6 months). (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). In a multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model dermatologic reaction was the only significant factor impacting OS. Patients who experienced DAE60 had an increase of survival of almost three folds of those who did not experience the event (HR = 2.7, CI 1.6-4.4; p < 0.001). Of the 17 patients who discontinued treatment in the first 60 days of sorafenib treatment, 16 did not developed DAE60. We performed an OS analysis excluding this 17 patients, and we continued to observe a significantly superior OS for patients with DAE60 versus those without it (31.2%; CI 95% 17.7%-44.7% vs. 15.6%; CI 95% 13.1%-18.0%, p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of patients with advanced HCC who used sorafenib, we demonstrated that dermatologic adverse events to sorafenib are associated with better outcomes. The patient profile in this series are patients with preserved hepatic function, mostly Child-Pugh A (85.6%) and asymptomatic (63% PS-0), but with a tumor in advanced stage. In fact, 80.3% of patients were in BCLC-C stage and 81% presented vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread at the start of the sorafenib therapy. In general, clinical trials on HCC only include patients with preserved liver function,6 , 14 since severe liver dysfunction represents a competing cause of death and may confound results.

In our study, presence of vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread correlated with the worsening PS, suggesting that PS is associated with the status of disease and with the tumor burden.

Despite the advance tumoral disease of most patients and sorafenib treatment interruption in 45% due soley to radiologic progression, the median duration of treatment in our study was 10 months and median OS was 20 months. Median treatment duration and OS were from 2.6 to 6.7 months6 , 8 , 20 and from (10.1-12.7) months respectively in other studies.6 , 8 , 14 The longer survival observed in our series may be in part explained by the practice of continuing sorafenib treatment despite the onset of AE. Adverse reactions to sorafenib, unless intolerable and/or uncontrollable, were not considered a reason for sorafenib discontinuation, but only to dose adjustment. In a recent prospective study,18 a protocol for dose reduction has been suggested to maintain the patient in the maximum tolerable dose even in the adverse events remains, but in a lower grade. This type of patient management would result in a longer sorafenib treatment duration and, consequently, extend survival time. The results of the same study showed that both the precence and intensity of the AE were predictive factors for a better survival. Another alternative explanation for the longer survival of this cohort may be that patients in this specific geographic region might have tumors with a less aggressive profile than patient included in the European studies, but this can only be speculated due to the lack of molecular data.

When trying to identify prognostic factors for greater survival, the BCLC classification and the presence of dermatologic reaction seemed to be the most impacting factors. Prior retrospective studies suggested the presence of dermatologic reaction as a predictor of OS in HCC patients under sorafenib treatment. Tumor control rate was 48.3% vs. 19.4% and the median TTP was 8.1 months vs. 4.0 months in the group of patients with and without skin toxicity in the first 30 days of sorafenib treatment, respectively.21 , 22 The association of early dermatologic reaction and survival was confirmed in a prospective study by Reig, et al. conducted on 147 patients (results focused on 107 patients who developed DAE60 > Grade II and required sorafenib dose modification), which demonstrated that the survival of patients with DAE60s was significantly better when compared with the rest of the cohort (18.2 vs. 10.1 months, p = 0.009), regardless of baseline characteristics.9 The results of our study showing a relationship between the development of DAE60 during sorafenib therapy and longer OS seem to confirm the role of early cutaneous toxicity as a surrogate marker of efficacy as previously observed in the prospective European study.9 In our study, patients with DAE60 had an increasesurvival of almost three folds of those who did not experience the event.

Diarrhea has been previously described as an AE to sorafenib associated with a better treatment response. 15 , 16 However, this finding has not been reproduced in a prospective study9. In the current study, diarrhea was associated with a better overall survival in the univariate analysis. However, the multivariate analysis adjusted for other variables, including DAE60, did not confirm the presence of diarrhea as a prognostic factor associated with better survival for patients receiving sorafenib for HCC.

In most settings, AEs are seen as negative events and they are the main reason for definitive sorafenib interruption in a relevant number of patients. However, sorafenib has an acceptable safety profile and these AEs are usually mild and easily manageable with regression after a period of interruption of therapy or dose reduction.

All but three patients presented at least one AE to sorafenib in our study.The As were not significantly different according to BCLC B-C staging, Child-Pugh A-B and score PS. These findings are similar to other studies. 7 , 8In the present study, 59.1% of all treated patients needed at least one dose modification due to AE development. In some patients the dose of sorafenib was reduced to half of the original dose (400 mg/day).

One may argue that minor adverse events maybe poorly recorded in patients' charts which would cause a bias in a retrospective study looking at adverse events, such as ours. However, our study included only two centers both with strict adverse reaction reporting rules. Therefore, we can feel confident that reporting bias on DAE60, if any, would be little, and probably, it would not have had a significant impact on our results.

A limitation of our study was that a direct comparison between survival of patients with and without DAE60 was performed instead of an adjusted competitive analysis. The latter analysis was not possible because the retrospective database used for this study stored information on all dermatologic reactions with onset in the first 60 days of sorafenib treatment, but the exact dates of the onset were not available. That is a possibility that patients who discontinued sorafenib before 60 days of treatment had less chance to develop DAE60 which may have introduced some bias in our results. In fact, of the 17 patients who discontinued treatment before day 60, 16 did not developed DAE60. To compensate for this limitation, we performed an OS analysis excluding these patients, and we continued to observe a significantly superior OS for patients with DAE60.

CONCLUSION

The onset of a dermatologic reaction should not prompt an immediate dose reduction, temporary interruption or discontinuation of sorafenib treatment. This type of AE must be closely managed to optimize patient's comfort and safety, while, when possible, maintaining sorafenib treatment. AEDs should serve as an incentive to continue sorafenib administration as it may be associated with a better response to treatment, and consequently, an improved survival. The identification of a reliable marker of anti-tumor efficacy can be extremely useful in clinical practice, as it helps determining the efficacy of the therapy and, when necessary, allowing to modify treatment strategy early on. Although our data is limited by the retrospective nature of the study, it indicates that the finding observed in the previous prospective study regarding the association of dermatologic reaction and improved survival is valid in our population of patients with HCC treated with sorafenib. Future studies are needed to optimize and individualize sorafenib treatment and, consequently, improve outcomes in patients with advanced HCC.

ABBREVIATIONS

AASLD: |

American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. |

AE: |

adverse events. |

BCLC: |

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification. |

DAE60: |

Early dermatologic adverse events (during first 60 days of treatment). |

HBV: |

Hepatitis B virus. |

HCV: |

Hepatitis C virus. |

HCC: |

Hepatocellular carcinoma. |

OS: |

Overall survival. |

PS: |

Performance status. |

TACE: |

transarterial chemoembolization. |

TTP: |

time to progression. |

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)