Introduction

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has been widely used in the treatment of patients with portal hypertension. One of the common complications associated with TIPS is the development of hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

HE is defined by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases as a brain dysfunction caused by liver insufficiency and/or portosystemic shunting; it manifests as a wide spectrum of neurological or psychiatric abnormalities ranging from subclinical alterations to coma.1

Based on the neurological and psychiatric abnormalities HE is graded from Unimpaired to Grade IV. Grades II-IV are categorised as ‘overt’ grades with clinical findings ranging from lethargy, apathy, disorientation for time, obvious personality change, inappropriate behaviour, dyspraxia and asterixis in Grade II to coma in Grade IV.1

Studies have shown that about 30% of patients developed new or worsened HE after TIPS.2,3 The pooled estimate of new or worsening HE was 32% in the study of Russo, et al.4 Post-TIPS, HE reduces quality of life.5 Furthermore, 10% of post-TIPS HE cases require a liver transplant or die.2 The more severe the HE the smaller the chances of survival.6

Several studies have been conducted to investigate predictors for the development and progress of HE in post-TIPS patients. Several factors, such as: higher patient’s age,3,7-12 female sex,13 comorbid diabetes mellitus (DM),7 etiology of liver cirrhosis,7,8,13 non-alcoholic causes of portal hypertension,13,14 ascites as the indication for TIPS,11 hypoalbuminaemia,13,15 high serum creatinine,8 hepatofugal pre-TIPS portal flow,16,17 high Child-Pugh score,8,18 high reduction of the portosystemic pressure gradient,19 reduced liver function,20 and placing an uncovered stent21 have all been variably associated with the post-TIPS HE. However, some of these possible predictors such as: age, sex, stage of cirrhosis, Child-Pugh score, indication for TIPS, hepatic arterial blood flow changes after TIPS or type of stent have been challenged by other studies.15,17,22-27 Some of the studies had sampled less than 100 subjects.8-10,16,19-21

The primary aim was to study the association of preexisting patient factors with the development of post-TIPS HE.

The secondary aim was to consider the subgroup of patients with refractory ascites, where knowing which patients are at high risk of developing HE after TIPS, could perhaps in some cases help to consider the alternative of repeated paracentesis. Repeated paracentesis is a commonly used alternative to TIPS for refractory ascites with lesser risk of HE.28 There has been a call for the predictors of post-TIPS HE to be found, to rationalize clinical decision making in this group of patients.29

Material and methods

Study design

This is a single centre, retrospective observational cohort study based on the analysis of clinical data collected prospectively in a departmental database. The research was submitted to the Research and Ethics Committee of the University Hospital who concluded that the project did not require ethical approval as it is a retrospective, anonymous survey.

Study sample

Patients, who underwent TIPS between September 1992 and August 2011, were included in the study. We excluded patients under 18 years of age and patients with an unsuccessful TIPS insertion. We also excluded patients with pre-TIPS HE.

Procedure

At the Internal Medicine Department, TIPS was first introduced in 1992. As this was a new procedure then, clinical data was carefully sampled to ensure the safety of patients was maintained at a high standard. Before the TIPS procedure was performed, the presence of physical co-morbidities, physical examination and blood test results were documented (Table 1 and Table 2). A standard TIPS procedure was performed.30,31

Uncovered stents were used until 2000, as stentgrafts (covered stents) were not available. Mix of covered and uncovered stents has been used since 2000. Due to the price of the covered stents, covered stents are being given to patients with longer life expectancy and if the patients are due to have a liver transplantation (temporary TIPS).

Shunt patency was assessed using Doppler ultrasound one month after TIPS and then three monthly.32 TIPS revisión was indicated in the case of significant stenosis of the shunt. Balloon dilatation or insertion of another stent was performed if needed. All patients in the study had patent shunt during the follow up period.

Assessment of HE

Our information about the development of overt post-TIPS HE was based on close follow up of patients after the TIPS procedure. Interview and a simple task such as asking the patient to provide a signature were used. Collateral information from family gave significant insight into the grade of HE. As this was a clinical setting, no battery of psychometric tests was used. No psychometric tests are needed for diagnosis of overt HE.1

Follow up

Patients had a daily review for 1 week during their inpatient stay after the TIPS procedure and outpatient follow up with a consultant hepatologist at: 1 month, 3 months and 6 months after the TIPS procedure. Further follow up appointments at 3-6 months were made thereafter. This was based on previous reports that most of the patients develop HE during the first 3 months after TIPS.2 Families and patients were educated to contact the hepatology service if any signs of HE appeared, and the hepatology nurse maintained frequent contact with the patients and their families. Additional urgent appointments with a consultant were provided if any complications, including HE, were suspected, and this was recorded accordingly.

Statistical methods

Data was analyzed using the statistical program SPSS version 19.033 and NCSS 9.34 Statistical significance was taken as p < 0.01 due to higher number of tested variables. We used Fisher exact test and χ2 test for categorical variables, and the Mann Whitney test for quantitative data, toidentify factors associated with development of HE. Statistically significant variables were used in the logistic binary regression analysis. For positively skewed values, the natural logarithm was used to improve the model.

We then used unpaired t-test to look for differences between group of patients with diabetes on oral versus insulin treatment, and for differences between group who underwent urgent TIPS.

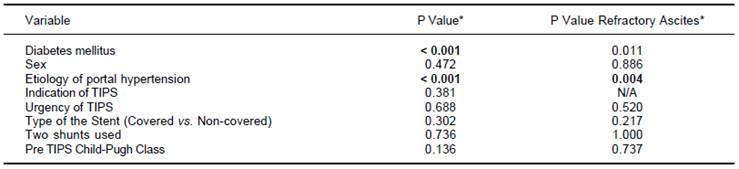

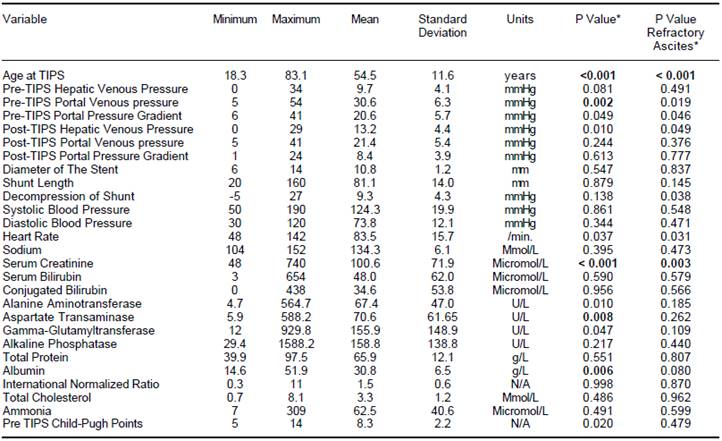

We then performed a separate analysis for the subgroup of patients with refractory ascites to identify the factors statistically associated with development of hepatic encephalopathy for this subgroup (Table 1 and Table 2).

* P-value refers to the differences between patients with and without HE using the Mann-Whitney test. Significant differences (P <0.01) were marked in bold. P values are uncorrected for multiple comparison.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of quantitative data.

Results

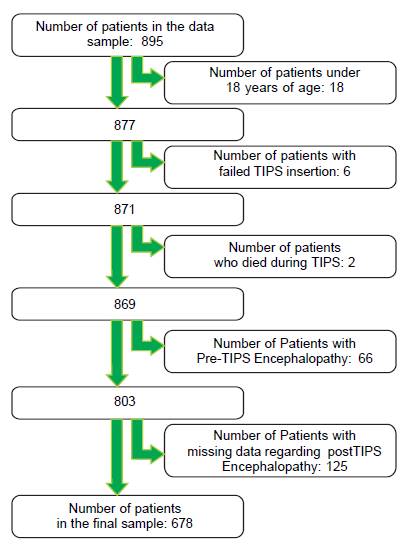

After applying the exclusion criteria (Figure 1), we obtained a final sample of 678 subjects. Most patients in the cohort were male (64%) with alcoholic liver disease (55%) and variceal bleeding (54%). There were 183, 320 and 166 patients with the Child Pugh score A, B and C, respectively. One hundred ninety-two patients had DM (79 on insulin). In 57 cases portal vein thrombosis was present prior to the TIPS procedure. For the purpose of statistical analysis, we have grouped the etiology of portal hypertension into following groups: viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic, cholestatic, vascular/non-cirrhotic, NAFLD/ cryptogenic, rare/congenital, multiple diagnoses/combinations. The descriptive statistics of the sample are summarized in Table 1, Figures 2 and 3.

The team used a covered stent in 234 (34.5%) cases. One hundred twenty-seven (18.7%) of the TIPS insertions were urgent. After TIPS, 257 (37.9%) patients developed HE. Fourteen patients required reduction of the shunt because of the severity of HE. Fifty-three of the patients who had undergone TIPS were later listed for orthotopic liver transplantation. The mean length of follow up after TIPS was 35 months. The mortality in 4 weeks was 11.5%; the mortality in one year was 37%.

We found 7 statistically significant variables associated with development of HE (p < 0.01) (Tables 1 and 2). High age, pre-TIPS portal venous pressure, serum creatinine, aspartate transaminase, low albumin, presence of DM and etiology of portal hypertension were all associated with the development of HE after TIPS. The regression model describing the development of HE after TIPS is summarized in Tables 3 and 4. In terms of he etiology of portal hypertension, 95% of vascular/noncirrhotic patients were HE free after TIPS. On the other hand, 64% of patients with viral hepatitis and 65% of patients with alcoholic liver disease did develop new HE after TIPS.

For patients with refractory ascites, the main variables associated with development of HE after TIPS were age and serum creatinine. The regression model describing the development of HE after TIPS in this subgroup is summarized in Tables 3 and 4. The etiology of portal hypertension was statistically significant for the subgroup however due to smaller frequencies it did not contribute to the regression model. 100% of the of vascular/noncirrhotic patients were HE free after TIPS and 65% of patients with viral hepatitis developed HE after TIPS. The alcoholic cause to portal hypertension was not significantly associated with HE after TIPS. Pre-TIPS portal venous pressure and DM were bordering on being significant and did contribute to the regression model.

The urgency of TIPS was not shown to be statistically significant. From our observations we hypothesized that this might be due to patients undergoing urgent TIPS being younger than those undergoing non-urgent TIPS. This difference was confirmed (p = 0.018, unpaired t-test).

DM was a strong predictor of HE. Interestingly, the patients treated with insulin did not statistically differ from the group of patients on diet or oral anti-diabetics (p > 0.8, unpaired t-test).

Discussion

This is a study of the association of preexisting variables on the development of HE. We confirmed the importance of age, pre-TIPS portal venous pressure, serum creatinine, DM and etiology of portal hypertension in the incidence of post-TIPS HE.

The regression models used were able to successfully sort around 60% cases. Therefore the models are suitable for description of the factors associated with development of HE and not for its prediction.

The association between hepatic encephalopathy and albumin levels, creatinine and aspartate transaminase is probably due to severity of liver damage.35,36 The pre-TIPS portal venous pressure, likely an indicator of severity of portal hypertension,37 was associated with hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS.

It was reported that older people are more likely to develop hepatic encephalopathy, possibly due to age-related vulnerability of the brain.38 This is in concordance with our findings that age is a very important predictor of HE after TIPS.

DM is associated with reduced psychomotor functions, a lower attention span and impaired memory.39 The pre-existing vulnerability of the brain could explain development of hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS for both older people and individuals with DM. TIPS affecting the homeostasis could trigger the HE if there was a preexisting condition.

Due to the benefit of having large data, we were able to confirm that previously reported sex differences in development of HE in small samples3 were more likely random findings.

There was no significant difference between covered and non-covered stents in terms of association with development of HE after TIPS in this study.

The percentage of alcohol-related portal hypertension cases in our sample was consistent with world literature.40,41

The etiology of liver cirrhosis complicated by portal hypertension is sometimes difficult to establish exactly in each individual. The self-reported alcohol consumption in the subgroup of patients who drink alcohol but also meet the criteria for NAFLD presents a diagnostic challenge. People in general have a tendency to report lower alcohol consumption than is their real consumption.42

NAFLD is one of the newer diagnoses.43 Therefore, some patients who might have been in the past given diagnosis of idiopatic cirrhosis might be nowadays diagnosed with NAFLD. This is the case especially for number of patients suffering from diabetes mellitus type II.44

It might be expected that the TIPS procedures performed urgently, and often associated with disrupted homeostasis, would be associated with HE. However, the fact that these patients were younger than those undergoing non-urgent TIPS could explain the result (as above).

Majority of the TIPS were done for variceal bleeding. However, there were only 18.7% urgent TIPS in the whole sample. This is because some of the TIPS were done preventively for patients with a history of multiple variceal bleedings. Nowadays, due to the improvements in endoscopic interventions, the number of patients indicated to preventive TIPS is decreasing.45

Ascites as the indication for TIPS was not associated with development of HE in our sample, unlike in other studies.11 As patients suffering with ascites usually have, as a group, bigger liver damage, one would expect that these patients would be at higher risk of developing HE after TIPS. The patients with portal hypertension from vascular reasons (Budd-Chiari syndrome) might still have a good liver function and hence lower risk of HE. We presume that the reason why indication for TIPS was not statistically significantly associated with the development of HE might be because some very unwell patients were included in the study overall.

In our sample, 65% of patients with alcoholic liver disease developed new HE after TIPS. This is in contrast with previous findings where non-alcoholic causes of portal hypertension were associated with HE after TIPS.13,14 We believe, that the likelihood of developing HE after TIPS depends on whether the person stops drinking alcohol after TIPS or not. If the person continues drinking, their cirrhosis is likely to get worse and their brain is likely to get more damaged. Around the time of TIPS procedure, the patients are offered interventions for alcohol problems when in hospital, and patients are more motivated to stop drinking. The key issue is that we are missing data about who abstained from alcohol after TIPS. This can cause a bias in our study as well as in the other mentioned studies.13,14 It is therefore difficult to conclude whether the alcoholic or non-alcoholic cause predisposed patients to developing HE after TIPS. 64% of patients with viral hepatitis disease did develop new HE after TIPS. The viral hepatitis more often progressed and led to worsening of clinical picture and development of HE.

In terms of the study limitations, the study was retrospective, which brings limitations such as inability to control for confounding factors, some missing data and lost to follow up. The TIPS is highly specialized procedure and therefore the centre covered a large geographic area making follow up attendance difficult for some patients from distant cities, leading to slightly higher lost to follow up.

As TIPS was used since 1992, its target patient group was not well established in the beginnings. This has led to some outliers in the sample, such as the patient with bilirubin of 654. Gradually the most unwell patients from the Child-Pugh grade C group started being excluded from TIPS referrals. Nowadays, TIPS is not indicated for patients with Child Pugh score over 12.

TIPS procedure is completed for all patients in a standard way. Very most of the patients had 10mm stent inserted. However, the impact on the Portal Pressure Gradient is individual. The lower mean of Portal Pressure Gradient might be also caused by some outliers in the mínimum range of the measurements.

High reduction of the portosystemic pressure gradient was reported to lead to development of HE.19 The higher the reduction of the portosystemic pressure gradient, the lower the risk of bleeding46 and the better are the chances that ascites will reduce. Clinicians are aware that the higher the reduction of the portosystemic pressure gradient, the higher the chances of developing HE due to reduced blood flow through liver.

The study presents real world data. This brings its own advantages and limitations. The diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy was made by hepatologists. In our opinion, this is not necessarily a limitation of the study. In practice, the diagnosis of overt HE is frequently made by hepatologists. HE prophylaxis was not recorded for statistical analysis due to the variability in individual prescribing based on clinical judgment. The results therefore represent the risks for an uncontrolled population of patients undergoing TIPS, rather than for a treatment naive population.

It was not the aim of the study to follow up of the development of HE in detail. It would be beneficial to see, in future prospective studies, how the symptoms of HE develop over time. Further studies could also focus on comparing the blood results at the time of any episodes of HE.

The study focused on differences in baseline characteristics of patients who did, and who did not, develop HE after TIPS. Since the study focused on correlation, it cannot draw conclusions about a causality between the baseline characteristics and development of HE after TIPS. It merely describes that people with a certain baseline characteristics are more likely to develop HE after TIPS, whether those characteristics are directly involved in thedevelopment of the HE or not.

We hope this large real-world-data study will help to conduct future studies focusing on specific predictors of HE after TIPS.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)