Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Economía mexicana. Nueva época

versão impressa ISSN 1665-2045

Econ. mex. Nueva época vol.20 no.2 Ciudad de México Jan. 2011

Notas

Markets vs. Government: Foreign Direct Investment and Industrialization in Malaysia

Mercados o gobierno: inversión extranjera directa e industrialización en Malasia

Bethuel Kinyanjui Kinuthia*

* Ph.D. student in the Tracking Development Project, African Studies Centre, Leiden University. The Netherlands. bkinuthia@ascleiden.nl

Fecha de recepción: 11 de junio de 2009.

Fecha de aceptación: 10 de marzo de 2010.

Abstract

This paper examines the changing role of government and foreign firms in Malaysia's industrialization process. Economists have held different views on the role of government in industrialization. Some believed that the developing world was full of market failures and the only way in which poor countries could escape from their poverty traps was through the forceful government intervention. Others opposed to this view argued that government failure was by far the bigger evil and that it should allow the market to steer the economy. Reality has been different from expectation for either side. From a country dependent on agriculture and primary commodities in the sixties, Malaysia has today become an export-driven economy spurred by high technology, knowledge based and capital intensive industries. The market oriented economy and the government's strategic industrial policy that maintain a business environment with opportunities for growth and profits have made the country a highly competitive manufacturing and export base. Multinationals have been at the forefront in this process and working hand in hand with the government through a process known as "hand holding". As firms move up the value chain their requirements change, and, to remain competitive in a global environment, the government has had to change its policies and approach to ensure that this objective is not compromised. In 2006 the government identified the service sector as the new driver for growth, which suggests a new era in industrialization. Based on this evidence we conclude that, for successful industrialization, developing countries will require flexible governments that facilitate the development of the private sector. This approach will generate greater benefits than would otherwise occur if developing countries were to adopt either government or market based development trajectories.

Keywords: industrialization, import substitution, export orientation, foreign direct investment, government.

Resumen

Este trabajo examina el papel cambiante del gobierno y las empresas extranjeras en el proceso de industrialización de Malasia. Los economistas han tenido diversos puntos de vista sobre el papel del gobierno en la industrialización. Algunos sostenían que el mundo en desarrollo estaba lleno de fallas de mercado y que la única forma en que los países atrasados podían escapar de su trampa de pobreza era a través de la forzosa intervención gubernamental. Otros, que se oponían a este punto de vista, argumentaban que la falla del gobierno era con mucho un mal mayor, y que se debería permitir que el mercado dirigiera la economía. La realidad ha sido diferente a lo esperado para cada una de las partes. De ser un país dependiente de la agricultura y los bienes primarios en los años sesenta, Malasia hoy en día se ha convertido en una economía que se mueve por las exportaciones, y que está estimulada por industrias de capital intensivo y alta tecnología basadas en el conocimiento. La economía orientada hacia el mercado y la política industrial estratégica del gobierno, que mantienen un ambiente de negocios con oportunidades de crecimiento y ganancias, ha hecho del país una base manufacturera y exportadora altamente competitiva. Las multinacionales han estado al frente de este proceso, trabajando mano a mano con el gobierno, a través de un proceso conocido como "llevar de la mano". Conforme las firmas ascienden en la escala de valor sus requerimientos cambian y, para seguir siendo competitivas en un ambiente global, el gobierno ha tenido que cambiar su política y enfoque para asegurarse de que este objetivo no se pone en riesgo. En 2006 el gobierno identificó el sector servicios como el nuevo impulsor del crecimiento, lo cual sugiere una nueva era en la industrialización. Con base en esta evidencia concluimos que, para que la industrialización tenga éxito, los países en desarrollo requerirán de gobiernos flexibles que faciliten el desarrollo del sector privado. Este enfoque generará mayores beneficios como ocurriría si los países en desarrollo adoptaran una trayectoria de crecimiento basada ya sea en el gobierno o en el mercado.

Palabras clave: industrialización, sustitución de importaciones, orientación de las exportaciones, inversión extranjera directa, gobierno.

JEL classification: B25, F13, O14.

Introduction

Ever since the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century, economic progress and development have been closely identified with industrialization. This thinking has continued to influence policy makers, especially in developing countries (Jomo, 1993). During the last two decades before the Asian crisis, East Asia re-emerged as the most dynamic region in the world economy, as it had been before the eighteenth century's rise of the West.1 Malaysia, located in South East Asia, is one of the fastest growing economies in the world and, in many ways, a Third World success story.2 From a country dependent on agriculture and primary commodities in the sixties, Malaysia has today become an export driven economy spurred on by high technology, knowledge based and capital intensive industries. The South East Asian success has been partly attributed to its ability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) and supportive government policies. Foreign manufacturing firms and governments have attracted extensive work by scholars seeking to appraise their role in industrialization.

Despite such intense interest, however, there is little consensus on their potential role. According to the classical theory, the benefits from FDI are derived through positive spillovers (Markusen and Venables, 1999; Aitken, Hanson and Harrison, 1997; Lensink and Morrissey, 2001; Blonigen, 2005). The classical proponents also advocate for a minimum government role in the market. Drawing from the experience of Latin American countries, proponents of dependency theory argue that relations of free trade and foreign investment with industrialized countries are the main causes of underdevelopment and exploitation of developing economies (Wilhems and Witter, 1998; Dos Santos, 1970). Due to the perceived exploitative nature of FDI, the dependency theory is in unison calling for adoption of state policies that are deliberately discriminative of FDI, in order to foster development of local industries and promote self reliance (Tandon, 2002; Wilhelms and Witter, 1998; Blumenfeld, 1991). These two contending views continue to dominate the theories that explain the role of foreign capital and government in industrial development.

Central to the development debate in South East Asia has been the role of industrial policy in development,3 with the World Bank (1993) arguing that industrial policy had no role in the industrialization process in South East Asia. Jomo et al. (1997), on the other hand, stress the importance of industrial policy to develop trade policy instruments which, although with mixed results, have nevertheless been part of the region's industrial policy story. As a result, these economies have been relying on FDI to develop most of their internationally competitive capabilities (Jomo and Rock, 1998). In the case of Malaysia, government policy has generally accorded a central role to foreign capital, while at the same time has been working towards a more substantial participation of domestic (especially bumiputera)4 capital and enterprise (Drabble, 2000). In this paper we focus on the role of industrial policy in attracting and utilizing FDI in Malaysia.5 A comprehensive analysis would require an extensive study of firms and government policies globally. Given the limitations of a paper, we restrict this analysis to study Malaysia6 to obtain a deeper and more informative analysis. The rest of the document is structured as follows. In the section I we discuss the process of industrialization in phases. In section II we discuss the lessons learnt, and lastly the conclusion follows.

I. Industrialization in Malaysia

Malaysia's industrial development can be classified into seven phases, according to the industrial strategies adopted. In the first phase (18671957), Malaysia was under colonial rule and the economy was largely limited to export of agricultural products and minerals, mainly rubber and tin, under free market. At independence, in 1957, there was a shift to the import substitution industrialization (ISI) strategy until the late 1960s. Although ISI was abandoned even if not entirely, towards the early 1970s there was a renewed emphasis with a new focus on export oriented industrialization (EOI), a strategy that lasted a period of ten years and was largely considered a success, except for the limited linkages between foreign and domestic firms. A second round of ISI was introduced from 1981 up to 1986 and was considered much of a failure, prompting the return to EOI in 1987, a period lasting ten years before the advent of the Asian crisis in 1997. After the Asian crisis a unique period followed, when the government pursued stabilization measures aimed at getting the ailing economy back on track. This period lasted close to eight years. The last phase captures the more recent period, when the Malaysian economy hopes to move towards global competitiveness, from 2006 onwards. We briefly discuss these phases in the next section.

I.1. Situation Before Independence

Since the late nineteenth century Malaysia has been a major supplier of primary products to the industrialized countries, due to the great demand from the West as a result of its growing population. The commercial importance of Malaysia was enhanced by its strategic position, athwart the seaborne trade routes from the Indian Ocean to East Asia. Merchants from both of these regions, Arabs, Indians and Chinese regularly visited the country (Drabble, 2000, pp. 149-177). At independence in 1957, tin and rubber in particular were the main export commodities in peninsular Malaysia7. The demand for rubber was high to the point that it quickly surpassed tin as Malaysia's main export, and FDI was the main force behind the growth of rubber cultivation. FDI also played an important role in market expansion for local producers, and was largely dominated by the British, Americans, French and the Dutch. As a result, FDI became so strong in Malaysia that in the 1950s there were 958 foreign companies in the Federation (Rasiah, 1995, pp. 50-53).

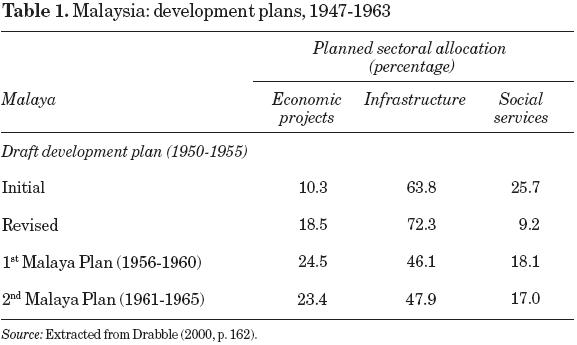

Malaysia's infrastructure was generally more developed than in almost any other British colony (Jomo and Rock, 1998). This was mainly because the colonial state used revenues generated specially from rubber and tin to finance infrastructural development (see table 1),8 most importantly railway lines, roads and ports. This expansion in infrastructure "subsidized" manufacturing growth, as it bore relatively small taxes during the colonial period (Rasiah, 1995, p. 53). Fiscal linkages also expanded in education and health, and this contributed to a steady growth of the Malaysian economy. This generated a sufficient demand to stimulate the deployment of Western firms in Malaysia. The colonial government emphasized mainly the production of export oriented raw materials and British manufactured imports. As a result, local industry was largely confined to processing raw materials for export and producing certain items for local consumption, especially if favored by preservation and transport cost consideration (Jomo and Edward, 1993). Thus, the development of domestic industry was largely under laissez fair conditions. By 1957, peninsular Malaysia was already exporting food, beverages and tobacco.

Rising demand for housing boosted the demand for cement and large scale wood processing. Manufacturing output grew by 15.3 per cent per annum in the period 1955-1957, and its contribution to GDP was only 8 per cent (Rasiah, 1995, p. 61). The absence of state subsidies and protection discouraged the growth of large manufacturing enterprises, and firms in Malaysia were small, averagely employing 20 workers, although the majority employed less than 10. They accounted for 6.4 per cent of employment in peninsular Malaysia (World Bank, 1955, p. 422). FDI was instrumental in the development of the manufacturing sector, and positive spillover effects were already flowing to the local firms, as well as market outlets, in the emergence of the modern manufacturing sector in Malaysia. There was already a substantial level of technology spill over from foreign firms to local firms. In addition to employee transfers, Western firms subcontracted engineering and construction work to local Chinese firms.

Towards the end of the 1950s technological innovations in the developed countries, which had previously imported rubber and tin from peninsular Malaysia, led to the production of substitute commodities for primary products, such as synthetic rubber, causing serious effects on the Malaysian economy, whose foreign exchange was dependent on tin and rubber, due to reduced prices and low demand. This necessitated a decrease in the reliance on tin and rubber, and so Malaysia adopted import substitution following recommendations from a World Bank study in 1955.

I.2. Situation after Independence

Industrialization in Malaysia is considered by many scholars (e.g. Jomo and Rock, 1998, and Alavi, 1996, among others) to have begun after independence of peninsular Malaysia in 1957, although as we have seen from the discussion above the manufacturing sector had already begun developing earlier. After independence in 1957, the new government embarked on the ISI strategy following the recommendation of experts. This strategy sought to encourage foreign investors to set up production, assembly and packaging plants in the country to supply finished goods previously imported from abroad. What existed was very largely a promotional effort geared to the provision of an investment climate favorable to the private sector, and more especially foreign private enterprise (Wheelwright, 1963, p. 69). To promote such efforts, the government directly and indirectly subsidized the establishment of new factories and protected the domestic market (Jomo, 1993).

The mobilization of this development potential for building the new independent Malaysian economy had, however, to be done under conflicting challenges posed by a plural society inherited from its colonial past. At that time, the natives, Malays, who accounted for 52 per cent of the population, dominated politics, but were relatively poor and mostly involved in low productive agricultural activities.9 The ethnic Chinese, who were about 37 per cent of the population, enjoyed greater economic power and dominated most of the modern sector activities, but did not match the ethnic solidarity or political power of the Malays. Therefore, economic policy making in post independence Malaysia turned to be a continuous struggle to achieve development objectives, while preserving communal harmony and political stability. Government policy during the first decade was consequently designed to suppress growing inter communal rivalries. The policy thrust was to continue with the colonial open door policies relating to trade and industry, while attempting to redress ethnic and regional imbalances through rural development schemes and the provision of social and physical infrastructure (Athukorala and Menon, 1996). Thus, the state pursued an economic policy of discrimination that favoured ethnic Malays over other races including preferential treatment in employment, education, scholarships, business, access to cheap housing and assisted savings.

Through this industrial policy the government focused on the development of infrastructure and the rural sector, while industrialization was left to the private sector; a decision that was largely a political compromise between the parties making up the ruling alliance. The United Malay National Organization (UMNO)10 realized that the Chinese and Indian acceptance of UMNO's political role was to some extent dependent on the state not interfering in private commerce and industry (which they dominated) beyond its regulatory role. Therefore, UMNO accepted (temporarily) the Chinese and Indian dominance of business and commerce, in exchange for their acceptance of UMNO political domination and UMNO efforts to increase the Malay participation in the rural sector and in the transportation, mining, construction and timber industries. World Bank's recommendations favoring industrialization under private sector auspices also influenced this policy (Kuruvilla, 1995). The state restricted itself to the creation of a favorable climate to attract foreign investment in import substitution industries. The state enacted the Pioneer Industries (Relief from Income Tax) Ordinance (PIO) of 1958, and also created the Malaysian Industrial Development Finance Corporation, which was responsible for providing investment capital and for the development of industrial estates.

These incentives, among others, attracted labor intensive manufacturing industries for the domestic market (Ritchie, 2004). Tax incentives had been offered to pioneering industries since 1958, but from the beginning of the 1960s, with the establishment of the Tariff Advisory Board, import-substitution was encouraged by providing protection through import duty and quotas, which was considered to have been the greatest incentive (Jomo, 1993); tax concessions merely made the protection even more valuable. This view was in contrast to Lim's (1973, p. 255), who claimed that protective tariffs were not used as a major instrument of industrial development for the period 1959-1968. It is estimated that the weighted average effective rate of protection rose from 25 to 65 per cent by the end of the decade. Thus, subsidies given by the structure of protection to manufacturing companies in Malaysia have been substantial (Jomo, 1993). There were also non financial incentives, which included a severe control on labor organizations; unions were not allowed in pioneering industries, e.g. textiles and electronics (Rasiah and Shari, 2001).

However, contrary to the proponents of infant industry protection, the imposition of tariffs was not part of a comprehensive strategy for spawning local firms. The main impetus for manufacturing came from foreign firms, which expanded their operations to benefit from the protected domestic market. Many of them merely carried out minor assembly of products, which they had just been marketing previously. Industrial investments were quite responsive to government efforts. British investors in particular, seeking to maintain and increase their colonial market share, made full use of the incentives, and especially so after the introduction of the Tariff Advisory Board, the creation of the Federal Industrial Development Authority (FIDA) [which later became Malaysia Industrial Development Authority (MIDA), aimed at spearheading the promotion and monitoring of manufacturing growth] and the enactment of the Investment Incentives Act, in 1963, 1966 and 1968 respectively (Rasiah, 1995, p. 76).

The ISI did in some way contribute to the development process in Malaysia. It helped to diversify the economy, to reduce excessive dependency on imported consumer goods and to utilize some domestic natural resources. It also created opportunities for employment and contributed to economic growth (Alavi, 1996). In addition, the pioneer industries program achieved its objective with the number of firms granted pioneer status, rising from 18 in 1959 to 246 in 1971. However, it was not long before the ISI was faulted. The initial role of FIDA did not bring the quick results the government wanted, and the implementation of ISI was poor (Rasiah, 1995, p. 77). The initial impetus to industrial growth soon petered out, as the frontiers of the domestic market were reached. In addition, the heavy importation of capital and intermediate goods used in the production of final consumer goods did not help alleviate the balance of payment problems, but instead aggravated them. Linkages with the domestic industry were limited, and the much needed reduction in unemployment did not take place, because of low labor absorptive capacity of the manufacturing sector and the much anticipated spillovers of surplus production into the export market did not take place (Alavi, 1996; Kind and Ismail, 2001).

The high profits earned as a result of protection caused companies to lobby Malaysian politicians and to offer them directorships on boards of subsidiaries of companies. As a result, rent seeking became widespread in Malaysia (Jomo, 1993). The local companies did not have an incentive to produce for exports; the ISI tended to be limited on final consumer goods, with the protection being higher on those goods than on the intermediate manufactures. It was foreign firms that benefited from ISI, and by 1970 more than three fifths of the manufacturing companies were foreign owned and enjoyed high profits which repatriated out of the country. There was also regional concentration of industries, causing large manufacturing plants to be concentrated in urban centers, while the smaller ones were unprofitable and pushed out (Jomo, 1993).

More importantly, although the ISI on one hand had by 1969 caused Malaysia's economy to grow by more than 5 per cent a year, being manufacturing growth rates high at 10.2 per cent annually11 as well as private investment increasing by 7.3 per cent, it did not lead to an increase in the economic participation of the ethnic Malays. Ownership of private capital among Malays still remained static, at 1.5 to 2 per cent (Kuruvilla, 1995), and mainly concentrated in unskilled jobs. In comparison, the Chinese had 22.8 per cent and the Indians 10.9 per cent; foreign interests accounted for 62.1 per cent, which made apparent that the ISI approach succeeded in strengthening the economic position of Chinese and Indians (Ritchie, 2004). This resulted in much anger and eventually led to the ethnic riots of 1969, and to a massive reversal in election results. The government was then forced to review its development strategies.

I.3. Export-Led Industrialization

By the end of the 1960s the limitations of industrialization based on ISI were becoming clear, and there was also a demonstration effect from the East Asian "Tiger" economies, which were pursuing export-oriented industrialization. In Malaysia this began with the enactment of the Investment Incentives Act in 1968, which widened the range of industries eligible for inducements, such as deductions for overseas promotional campaigns, exemption from payroll tax for companies exporting more than 20 per cent of total production, and so on (Drabble, 2000, p. 237). The government, in response to the social tension of 1969,12 launched the New Economic Policy (NEP), which coincided with the change in the direction of the industrial policy, from ISI to export-oriented industrialization strategy (EOI), a switch that gave fresh impetus to industrial growth (Jomo and Edwards, 1993). This new emphasis was supported by the NEP, whose primary objective was to eradicate poverty irrespective of race and to eliminate the identification of occupation with race and ownership of assets.13 Manufacturing was considered a strategic sector for the achievement of these objectives, and therefore the industrialization strategy during the second and subsequent Malaysia Plan periods was aimed at addressing the objectives laid down in the NEP.

By the early 1970s, government efforts to encourage export oriented industries were in full swing. Free trade zones (FTZS) and Licensed manufacturing warehouses (LMWS) were established to facilitate and encourage Malaysian manufacturing production for export using imported equipment and materials based on targeting foreign firms. The existing infrastructure, political stability, large supply of trainable labor force, a friendly government and financial incentives were important factors that led foreign firms to relocate their operations in Malaysia (Rasiah, 1995, p. 79). Such export industrialization strategy was consistent with the emerging new international division of labor, with transnational industries relocating different types of production, assembly and testing processes to secure locations offering reduced wages and other production costs.

The development of export processing industries in Malaysia was rapid indeed; two main types of export oriented industries developed. Firstly, resource based industries, which were involved in increased processing of older (rubber and tin) and newer (palm oil and timber) primary commodities for export. The processing of these natural resource based exports continued to grow for some time, but growth was constrained by an increase in production costs, tariffs and other trade barriers from governments in industrialized countries, who preferred importing raw materials. It is non resource based exports that have by far been more important since the 1970s in terms of growth and employment. This growth was concentrated in the FTZS and LMWS (Jomo, 1993), which became a very important component in developing Malaysia's manufacturing sector, and unique among developing countries establishing these zones.

In order for government to prevent future re-emergence of ethnic tension, it had to ensure that the growth now generated was distributed in line with NEP objectives. As a result the State, for the first time, became a significant actor in ISI investment. ISI was not abolished with the introduction of EOI policy. The involvement of government in ISI investment generated fears of nationalization, which resulted in a temporary reduction of private and foreign direct investment. As a result, private sector investment fell drastically from expected levels of 12 and 14 per cent to about 3 per cent of GDP in 1976. This shortfall and the utilization of government funds to buy shares (undersubscribed by the Malay business community for which they were reserved) resulted in a major resource crunch, which led to borrowing from international banks, raising foreign debt from 8.45 per cent in 1975 to almost 11 per cent of GDP by 1967-1977. This resource crunch led the government to articulate a mixed policy. The government decided to increase its involvement in the development of heavy ISI mainly because there was a fear that the target of 30 per cent ownership of corporate wealth14 by the Malays by 1990 was likely not to be achieved, since by 1978 the Malay participation had only reached 12.4 per cent (Kuruvilla, 1995).

In addition to ISI, the government encouraged private and foreign direct investment during the period 1977-1980 through policies emphasizing investment incentives, the development of infrastructural facilities, numerous taxes, labor and other incentives. Electronics and textile industries were specifically targeted, and most of these foreign firms were labor intensive. Initial entry in the electronics industry involved manual assembly of semi conductors. It was followed after some time by similar assembly in audio and other electric and electronic products. Foreign companies manufacturing for export were exempted from the Industrial Coordination Act (ICA)15 policies on Malay share ownership, and labor laws that might have discouraged foreign investment were relaxed or went without being enforced. Unions were excluded from key industries and the export sector (Lall, 1995). This new phase saw the beginning of massive foreign investment in the electronic sector by the US and Japan companies (Kuruvilla, 1995). Hence, low wages and a favorable investment climate accounted for Malaysia's early export growth.

By the end of the 1970s foreign firms contributed with a significant proportion of fixed assets, output and employment (Rasiah, 1995, p. 80). Employment expansion was significant and absorbed labor surplus, but was mostly in low wage employment (Kanapathy, 2000; Simpson, 2005). Although ethnic based intervention increased after the 1970s, it had little effect on foreign investment, as export processing foreign firms continued to enjoy total equity ownership. The government subsidized these firms through the introduction of incentives. However, the administration of FTZS and LMWS introduced bureaucratic restrictions that prevented the development of links between them and firms operating in the principle custom areas. Firms applying for financial incentives generally had to meet high levels of exports and imports (Rasiah, 1995, p. 79).

On the other hand, EOI did exhibit several concerns. It had had little effect on net foreign savings, which had been a major criticism of the ISI strategy. Also, in as much manufacturing employment had managed to increase significantly during this period, wages within the FTZS were very low; in fact, by 1978 the average real wage in the manufacturing sector was lower than in 1963. There was very little technological transfer or development of skills in the industries established in the EPZS, and few linkages with the rest of the economy. The degree of linkages between FTZ firms and the domestic economy, through the purchase of domestically produced raw materials and capital equipment, had been disappointing (Jomo, 1993). The export of manufactured goods was also limited to a narrow range of products, and there was a minimum development in the manufacturing sector (Lall, 1995). These concerns caused the government to reconsider its development policy, which ushered in the second round of ISI in Malaysia.

I.4. Second Round of ISI Strategy

In order to redress the problems of EOI in the 1970s, a second round of ISI based on heavy industries was launched. This strategy was aimed at deepening and diversifying the industrial structure through the development of more local linkages, small and medium enterprises owned by the indigenous (Bumiputra), and indigenous local capabilities. The export oriented industries were beginning to face competition and were looking for new avenues to sources of local materials, including labor, since wages had already begun to rise. This realization took place as a result of a world recession in 1980, which caused adverse effects on the Malaysian exports. Export earnings, which were doing well in the 1970s, were now threatened, and prices of most major export items declined sharply. The Malaysian ringgit appreciated steadily in real terms, posing serious problems on the export of manufactured goods. During this time imports continued to grow, especially capital goods, causing balance of payment problems to Malaysia for the first time (Alavi, 1996).

With a substantial EOI sector, superimposed on ISI which had been promoted during the 1960s, the government in 1980, through Dr. Mahathir Mohammed, the minister in charge of industries, announced a heavy industry policy geared to achieve the twin objectives of accelerating industrial growth and improving the economic position of the Malays. The heavy industries targeted under this new program included the national car project, motorcycle engine plants, iron and steel mills, cement factories, a petrol refining and a petrol chemical project, and a pulp and paper mill (Kanapathy, 2000). The government established the Heavy Industries Corporation of Malaysia (HICOM) in 1980, a public sector company to go into partnership with foreign companies in setting up industries in the areas identified above. These industries were expected to "strengthen the foundation of the manufacturing sector [...] by providing strong forward and backward linkages for the development of other industries" (Athukorala and Menon, 1996).

The ISI strategy had been modelled after South Korea, which had vigorously promoted heavy industry since 1972-1979.16 This model was similar to the "Look East Policy" that the Malaysian Government adopted under the leadership of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammed (Jomo, 1993). This policy seems to have initially appeared as a campaign to promote more effective modes of labor and discipline associated with the Japanese, but it was subsequently seen as a fairly wide ranging series of initiatives to become a "newly industrialized country" by emulating the Japanese and the South Korean "economic miracles". The implementation of this program led to a public development expenditure for heavy industries, rising significantly from RM17 0.33 billion in 1981-1985 to RM 2.33 billion between 1986 and 1990, mostly financed through external borrowing. This led to a rise in total foreign debt from about $15.4 billion in 1981 to $50.7 billion in 1986, the latter being at 76 per cent of GNP, far above the average for less developed countries (47.9 per cent) (Simpson, 2005; Drabble, 2000, p. 261). The external borrowing led to an appreciation in the real exchange rate, making the manufacturing sector less competitive, which resulted in slow growth.

Apart from an enormous injection of public funds, the targeted industries were heavily protected through tariffs, import restrictions and licensing requirements. For instance, the effective rate of protection for the iron and steel industry rose from 28 per cent in 1969 to 188 per cent in 1987. The level of protection for motor vehicle assembly and cement industries was so high, that these industries operated at negative value added at free trade prices. In other words, they would not have survived without protection (Kanapathy, 2000). In addition, the state also made efforts to enable the motor plant to purchase components and parts from FTZ firms (Rasiah, 1995, p. 81). The state also began to encourage foreign firms, particularly those enjoying financial incentives to integrate production vertically and expand local sourcing. It extended further financial incentives to foreign firms through the Promotion of Investment Act (PIA) in 1986. With this, the government provided investment tax allowance (ITA) to firms whose pioneer status had expired, and gave several generous benefits for export promotion, research and development and training (Rasiah, 1995, p. 82). However, these policies were not properly coordinated (Rasiah, 1995, p. 81; Jomo, 1993).

The world global recession in the early 1980s and the second oil shock worsened the situation, as the government embarked on counter-cyclical expenditure with the hope of stimulating the economy. The heavy development expenditure caused a huge rise in the budget deficit, and due to uncertainty interest rates rose and servicing debts became difficult. The second external shock led to a decline in world prices, and in turn to decreases in prices of important export commodities in the mid 1980s. Oil prices fell by 50 per cent, rubber prices by 7 per cent, tin prices by 47 per cent and palm oil prices by 63 per cent (Simpson, 2005). By this time, Malaysian manufactured exports had grown enough to offset the declines in primary commodities (Crouch, 2001), although manufactured imports also increased substantially (Jomo, 1993).

Foreign firms within the FTZ continued to dominate manufactured exports, with firms in electrical and electronic products taking the lead and having accounted for 15 per cent of manufactured output in 1981 and 23 per cent in 1986, but at least half of the total manufactured exports since 1981 (Simpson, 2005). The recession of 1985, believed to have partially been caused by a reduction in the global semiconductor industry, contributed in part to a loss in Malaysia's competitiveness, leading to a drop in manufactured exports compared to 1984. During the period 1984-1986 the manufacturing sector, particularly labor intensive industries such as electronics and textile, laid off about 100 000 workers. This constituted a significant proportion of Malaysia's working population of about 5.95 million in 1985. GDP also contracted by 1 per cent in 1985; the first negative growth rate in the country's modern economic history (Onn, 1990).

The recession was accompanied by an outflow of capital, causing the exchange rate to fall sharply in 1986. This depreciation of the exchange rate led to a reduction in the cost of production in Malaysia, as real wage costs declined over the mid 1980s with the rise in unemployment, as well as new labor policies and laws weakening organized labor's bargaining power and enhancing labor flexibility. In addition, this depreciation of the exchange rate coincided with the relaxation of the guidelines imposed under ICA and a reinforcement of tax concession under PIA (Jomo, 1993). These factors made Malaysia a very attractive place for investment, and combined with external market conditions resulted in a resurgence of export oriented foreign firms. This also led to an improvement in Malaysia's balance of payment position.

The recession was also a blessing in disguise, as unemployment in 1985 soared to 7.6 per cent. This prompted more people to start their own businesses and initiate self employment. The establishment of small and medium enterprises (SMES) was seen as important not only to address unemployment, but also to deepen the industry, and the government in the 1985 budget granted them a special rebate of 5 per cent of adjusted income for five years, and another 5 per cent if the manufacturing company complied with the NEP requirements. Under the PIA of 1986, small businesses received all the incentives previously enjoyed only by big firms. With strong emphasis from the government to achieve revitalization and industrial deepening, the number of loans allocated for SMES in 1985 increased considerably. The importance of SMES in Malaysia had been stressed earlier in 1982 in a World Bank report. By 1985, SMES in Malaysia accounted for 75 per cent of the total number of firms in the manufacturing sector (15 068), contributed with about RM 1.02 billon in fixed assets, and generated about 54.3 per cent (124 000) job opportunities in 1985 (Onn, 1990).

Based on the challenges the manufacturing sector was facing in the 1970s, the government was justified in establishing heavy industries. Unfortunately, this strategy did not yield the desired results. The Malaysian government begun to experience stiff international competition and required heavy protection, without which most industries could not have survived. The government argued that, since the local Chinese that dominated manufacturing industry had neither the interest nor the technology to invest in projects that offered uncertain returns, it turned to foreign investors to establish joint ventures. As a consequence, this heavy industrialization strategy became overly dependant on foreign partners, contractors and consultants (Simpson, 2005). The recourse to external funds helped public enterprises to escape the surveillance and discipline that could have been imposed by the federal government had there been a greater reliance on the Treasury as a source of funds (Jomo, 1993).

At the same time, the performance of the heavy industrialization program was weak. Being capital intensive, it was expected to have long gestation and payback periods, but even relative to these expectations, its performance was disappointing (Jomo, 1993). The state-owned industry had poor financial returns or even negative, and the lack of experience and capabilities led to prolonged teething problems (Lall, 1995). The failure of ISI was due to the absence of efficient enhancing intervention by the government (Rasiah and Shari, 2001). With all these weaknesses the government had no choice but to revert to EOI, and this time the government established a comprehensive plan that would address the problems in the manufacturing sector.

I.5. Second Round of EOI Strategy

During this period, the government embarked on reforms aimed at addressing the challenges in the1980s. With a reorientation of the economy towards exports and new incentives to attract foreign firms, Malaysia registered a tremendous growth in the 1990s. The government established new institutions as well as reconstituted the existing ones to cope with the new challenges posed by high growth. In spite of doing so, problems related to competitiveness of local industries became pronounced, and selective policies began to be employed to address this issue. Foreign firms began to upgrade their products as they moved to the higher end of the value chain to remain competitive. However, this proved to be a real challenge that demanded a rethinking of development, as the country was now facing a globally competitive environment and a tight labor market.

The sluggish performance of private investment (both domestic and foreign) in industry in the early 1980s, combined with falling official revenues, led to the formation of plans specifically focused in the manufacturing sector. The first of these major planning instruments for Malaysia as a whole was the Industrial Master Plan (IMP) of 1986. The IMP concluded that the ISI sector had not developed behind tariff protection to the level where industries were competitive internationally, and that the EOI sector was still narrowly based on two major industries, electronics/electrical machinery and textiles, which accounted for 65 per cent of manufactured exports in 1983. It was also noted that the expected spillover effects were not forthcoming, as almost 90 per cent of components in semiconductors were imported, there was dependence on foreign technology and only limited amounts could be transferred, a lack of skilled workers, and inadequate incentives to expand exports (Drabble, 2000, p. 257). The IMP was to last from 1986 to 1995 and provided a long term indicative plan for the development of specific sub-sectors, policy measures and areas of special emphasis.

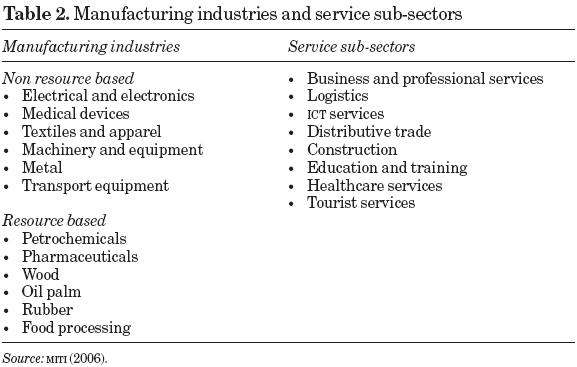

The recommended policy was implemented to enhance private investment and develop a more focused policy reorientation. Twelve sub-sectors were given high priority status. These comprised seven resource-based industries and five non resource-based industries to be developed over the ten year period. The resource based industries were food processing, rubber, palm oil, wood based, chemical and petrochemical, non ferrous metal product and non metallic mineral product industries. The non resource industries were: electrical and electronics, transport equipment, machinery and engineering, ferrous metal, and textile and apparel industries (Alavi, 1996). The main focus points were a renewal of export orientation and a more liberal trade regime. Based on the IMP recommendations, fiscal incentives to promote investment were consolidated and major improvements were made to induce investments, linkages, exports, training, and research and development. The list of products to be promoted was under continuous review, and a program for industrial rationalization and restructuring to enhance industrial efficiency was launched. The incentive system was tied to industries in which Malaysia had a comparative advantage and to those products of strategic importance for the country, hence the term "priority products" (Kanapathy, 2000). The government went ahead to privatize most of the state owned enterprises.

The industrial incentives were given not only through PIA and ICA, alluded to earlier, but also through investment tax allowance (ITA) and a major revamp of the export credit refinancing facilities (CER), among other generous incentives. The most attractive incentive was the extension of tax relief for a further five year period to companies that incurred in expenditure of fixed assets of RM 25M or more, or companies that employed 500 employees or more, or companies meeting other requirements which in opinion of MITI would promote or enhance economic or technology development of the country at the end of the initial tax period of five years. There were also special incentives to support the development of SMES that were deemed essential to develop industrial linkages. Foreign equity guidelines were further relaxed to make it easier for foreign investors to own up to 100 per cent equity, depending on export targets and other conditions (Alavi, 1996; Kanapathy, 2000).

In 1987 the government also froze wage increases for three years, aimed at consoling foreign firms fearing increases in the cost of production. At the same time, MIDA18 was overhauled by the government to become a one stop investment shop under a new name, Centre of Investment (COI), where new and potential investors could go to resolve their problems and concerns. MIDA also started to use incentives to guide FDI into higher value added activities and more technology intensive processes. Prospective investors in areas of advanced technology were also targeted. In addition, MIDA introduced incentives to encourage local content, and began to proactively reach out to investors across the country, to connect them to approving authorities, assist them in submitting applications, and to act as a mediator between investors and approving authorities in expediting approvals. MIDA was now involved in assisting firms from inception to their last day of operations in Malaysia; a process that later came to be known as "hand holding". To do so they established offices in all the 12 states,19 with special project officers handling firms' issues in each state (MIDA, 2008).

As a result, FDI responded vigorously in the latter half of 1980s, mainly from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Japan also continued to relocate their assembly operations in Malaysia, as the yen strengthened and induced many of their suppliers to invest with them. The manufacturing sector continued to grow surpassing all expectations and becoming the leading sector in output, export growth and employment. This growth in manufacturing employment was accompanied by rapid increases in both Malay employment and female employment. By this time, Malay participation was also increasing in the government sector; hence, the growth in industry and services coupled with NEP restructuring stipulations helped to reduce identification of ethnicity with economic function and urban or rural location (Jomo and Edwards, 1993).

With all these changes, the Malaysian economy grew fast averaging 5.9 per cent between 1980 and 1990, which was slower than the earlier decade when it had grown at an average rate of 8.3 per cent20 (Kanapathy, 2000). The uninterrupted growth from 1986 transformed the labor market from a situation of high unemployment in the mid 1980s to severe labor and skill shortages by the early 1990s, with a significant inflow of foreign workers (Kanapathy, 2000). By 1997 foreign workers constituted 20 per cent of the labor force. The significance of foreign workers assisted in moderating wage increases, even though wages grew in excess of productivity. In addition, skill intensity in manufacturing was almost stagnant during the period of high growth, and the level of technical and tertiary education was insufficient to meet the growing demand for skilled workers (Ritchie, 2004). The shortage of skilled workers led to high wage premiums, dampening investment in skill intensive industries (World Bank, 1995).

This led to the replacement of NEP in 1990 with the New Development Policy (NDP), which was largely considered a success by the government having realized its main objective of using industry as a vehicle for growth and poverty reduction and increasing Malay participation in the private sector, despite its failure to achieve the targeted 30 per cent Bumiputra corporate equity participation in the economy. More importantly, Malaysia had become one of the most successful economies in Asia, prompting the World Bank (1993) to refer to this success as the "East Asian Miracle"21 and one of the best performers in the developing world over the past 25 years (Lall, 1995).22 NDP was based on a more coherent and systematic analysis of the needs and capabilities of manufacturing activities. It aimed at addressing the weaknesses of NEP with more emphasis on human capital development and the role of the private sector.

Although NDP maintained most of the components contained in NEP, it made the application of those requirements more flexible and contingent on performance, particularly export manufacturing. The redistributive priorities of NEP gave way to developmental priorities which included increasing labor supply, boosting the level of skill in the local workforce, advance technology in both foreign and local firms and increase the amount of local content in foreign owned export manufacturing (Ritchie, 2004). Technology had been the weakest point in Malaysia (Kanapathy, 2000). This has been attributed to the failure of previous policies and incentives to encourage technology transfer, but that rather emphasized increased output, employment and exports by multinationals.

Bearing this in mind the government resolved, through NDP, to address this anomaly by reforming and expanding public sector research and development institutions, infrastructure, and the introduction of a wide range of incentives for private sector development. Increasing the technological capacity of the country required that firms upgraded the technological content of their products and processes. To improve the quantity and quality of local firms capable of supplying multinational corporations (MNCS), the government through MIDA changed the investment structure in favor of MNCS that were meeting its stringent rules of technological requirements and sharing. In addition, efforts were made to improve developmental linkages between foreign and local firms. In 1993 MIDA launched the Vendor Development Program(VDP), in which more technologically advanced firms, usually MNCS, were given incentives to mentor upgrading processes in local vendors, which they facilitated through guaranteed contracts, a free interchange of engineers and product specification, loans with preferential terms from local banks and ongoing technical assistance from public research institutes (Ritchie, 2004).

To address the labor problem, the government also established in 1993 the Human Resource Development Corporation (HRDC) to facilitate firm level training through the Human Resource Development Fund (HRDF). Firms meeting the NEP thresholds were levied 1 per cent of their employees' salaries, which was deposited in firms' specific accounts available for government approved training. This training reform became very successful, and by 1997 committed training places had climbed to 533 227 with over RM 144 million collected and RM 99 million dispersed. In 1996 the government launched the Small and Medium Industries Development Corporation (SMIDEC), in recognition of the need for a specialized agency to further promote the development of SMES in the manufacturing sector through the provision of advisory services, fiscal and financial assistance, infrastructural facilities, and market access, among others. The industrial linkage program was now brought under SMIDEC, whose main aim was to support SMES in a globally competitive environment. It was involved in skill upgrading programs all across Malaysia, indicating the government's recognition of SMES (Ritchie, 2004).

In 1993 the government further strengthened ties with industry through the establishment of the Malaysian Business Council (MBC), The Malaysia Industry-Government Group for High Technology (MIGHT) and the Malaysia Technology Development Corporation (MTDC) to promote public-private Corporation for upgrading. Both MBC and MIGHT brought most of the important business leaders and key government administrators and directors together in regular consultative meetings. In addition, public research institutes such as the Malaysian Institute of Micro Electric Systems (MIMOS) and the Standard and Industrial Research Institute of Malaysia (SIRIM) were created to promote basic and early state research and development in the budding technology sector, and to supply development assistance of local firms. In that same year Khazanah Holdings was formed to invest in new high tech ventures (Ritchie, 2004).

By 1995, multinationals had dominated the production of exports in Malaysia, unlike Taiwan and South Korea, where it has been dominated by local firms. During this period, Malaysia registered a very impressive growth in all sectors compared to the 1980s. However, the failure to develop sufficient domestic linkages in Malaysia resulted in the growth of industries with a high import content of capital formation and industrial output. To nurture a more robust industrial sector and retain more value added in the economy, there was the need to avoid FDI with low potential for linkages with the local economy, and attract FDI conducive to developing indigenous supply capacity. This would continue being a challenge for policy makers, as investing MNCS are not always sympathetic to the needs of the country (MITI, 1996). Due to the rapidly changing domestic and global environment, there was the need for Malaysia to change its strategy. Wages in Malaysia were escalating, and the industry had to compete with low wage new comers, mainly India and China, which with a large domestic market were largely promoting themselves as low cost-export platforms. The internal and external challenges facing the industrial sector meant that past industrialization approaches based on large scale injections of capital to boost labor productivity were no longer viable, and led to the introduction of the Second Industrial Master Plan (SIMP).

I.6. Cluster Based approach to Industrial Dynamism

With the reality of Malaysia operating in a globally competitive environment, the government did not have much of a choice but to refocus its development strategy through the Second Industrial Master plan. The new focus was cluster-ased approach, and key strategic sectors were identified for development. The emphasis was on value addition through increased productivity. Once again, new institutions had to be established to meet this new challenge, and incentives were given to multinationals that were using high technology and were willing to share with local firms. The use of selective policies has been common in Malaysia. At the same time, the government embarked on infrastructure development as well as development of high skilled labor. The Asian crisis was a set back, but Malaysia was able to mitigate its effects through sound macroeconomic policies and get back on tract. However, in spite of all efforts Malaysia was not able to meet its economic targets by 2005. The manufacturing sector had begun to show signs of decline from 2000, and debate of de-industrializing began; this prompted the introduction of the third IMP to address these challenges.

Dubbed the manufacturing ++ (plus-plus), the second IMP , launched in 1996, was formulated at a time of widespread labor and skill shortages and increasing global competition, and focused on increasing productivity and competitiveness. It was built upon the foundations of the first IMP . With the second IMP the focus shifted from the traditional industrial base to a cluster-based approach. It emphasized the development of industrial clusters, their key suppliers and the requisite economic foundations such as human resources, technology, physical infrastructure, supportive and administrative rules and procedures, fiscal and non fiscal incentives, and business service support. It aimed to develop dynamic industrial clusters and strengthen industry linkages, while promoting higher value added activities. Or better still; the emphasis was to move the manufacturing operations from mere production to include research and development, design capability, development of integrated support in favor of industries, packaging, distribution and marketing through the manufacturing plusplus strategy. This manufacturing strategy not only entails moving along the value chain, but, more importantly, shifting the value chain upwards through productivity growth (MITI, 1996).

The clusters at different levels of evolution were of various kinds. The natural evolving clusters were mainly resource based, including wood, rubber, palm, petroleum and chemicals. Policy driven clusters involved mainly the heavy industries established during the ISI strategy, and included automotive, aerospace, machinery and equipment, which are largely considered strategic. The third level consisted of clusters with international linkages, which included electronics and electrical appliances, and textile industries (MITI, 1996). In 1996 the government of Malaysia launched the first investment in its technology based future, called the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC). Conceived as a super high technology park, the MSC was intended to enable Malaysians to participate in and benefit from the global information revolution. It was planned to be a high-tech hub for government and the private sector, based on the concept of intelligence offices providing fast and easy transport of data, domestically and internationally, through the use of a world class voice and data communication network. It was intended to act as a magnet to attract the world's most advanced, high tech research and development companies to Malaysia. The government foresaw MSC operating as a test bed to be used by information technology and multimedia researchers from around the world. The outcome of MSC is to enable Malaysia to leap into knowledge intensive industries through the development of people, infrastructure and applications (Jusawalla and Taylor, 2003).

A Multimedia Development Corporation (MDeC) was established in 1996. The MDeC implements and monitors the MSC program, processes the applications for MSC status, and advises the government on MSC laws and policies. An MSC International Advisory Panel (IAP), made up of experts and corporate leaders from the global community and Malaysia, was instituted to provide advice on the MSC (Yusuf and Bhattiasali, 2008). Recognizing the enormous gap existing between Malaysia and other developed countries, the government hoped that MSC would be a vehicle to attract hightech multinationals that would be willing to share some of their skills with Malaysian firms. Through MIDA, a set of very attractive incentives were set aside for this.

The government also established institutions to provide skilled workers in order to ensure that such plans did not falter. It also encouraged the formation of private technical institutions to meet this demand. The privatized Telcom Malaysia began a Multimedia University; the first cohort of 1300 students was admitted in 1998. The government also reviewed laws that would have hindered the formation of competitive industrial clusters at a national level, to enhance the supplying capability of SMES and to encourage Malaysia to develop original brand name products, in order to grow into multinational corporations. By January 2002 MDeC had surpassed its target of achieving 500 MSC status by 120 companies, and raised the target to 750 in 2003. Included in this number there were 50 world class companies that it had managed to attract. Through MIDA and MDeC multinationals were now encouraged to establish their headquarters in Malaysia (Jusawalla and Taylor, 2003).

The continuing expansion of the Malaysian economy, together with foreign inflows in the early and mid 1990s, mounted pressure for upgrading until the bottom fell out of the economy in late 1996 and early 1997, with the emergence of the Asian Crisis (Ritchie, 2004). Following the devaluation of the Thai bhat, a wave of speculation hit Malaysia, and with its foreign exchange reserves down to US $28 billion, the ringgit was allowed to float in April 1997 to stem the speculative attacks. Between the beginning of floating and January 1998 the ringgit had depreciated by about 50 per cent against the dollar. The crisis in Malaysia was characterized by a significant and dramatic reversal in foreign portfolio capital, a reflection of the stock market boom that had preceded the crisis (Menon, 2008). Other reasons include a combination of excess investment, high borrowing (much of it in dollar denominated debt) and a deterioration of the balance of payments (Giroud, 2003).

Malaysia was however able to stop the slide in its currency and stock markets without the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This crisis prompted the government to make some fundamental changes in its policy towards investment, which included cutting government spending by 18 per cent, postponing indefinitely all public sector investment projects, freezing new company share issues and company restructuring, and banning new overseas investment by Malaysian firms. Thus, the government decided to temporarily disconnect the domestic capital market from the global economy, in order to pursue its stimulatory policies (Menon, 2008).The weaknesses facing the manufacturing sector had been worsened by the Asian crisis (Giroud, 2003). Through sound macroeconomic management the economy made a massive turnaround in 1999, and the annual growth rate went to an impressive 5.4 per cent compared to a contraction of 7.4 per cent in the previous year (Menon, 2008). Growth accelerated to a remarkable 8.9 per cent in 2000, and the economy regained its pre crisis level by mid 2000, except for FDI, which has taken time. Also, the government further liberalized the economy in 2000, and removed some of the restrictions imposed to FDI, such as local content requirements, in line with WTO regulations (Yean, 2004).

By 2000 the manufacturing sector had become the most important contributor in Malaysia, but started to show signs of contraction. This was because of a loss of competitiveness caused, on one hand, by rising production costs deriving from tightening labor market and, on the other hand, by the expansion of cheap exports from China, Vietnam and LDCS (Rasiah, 2008). At the heart of the problem lied the incapacity of Malaysian firms to take the transition to higher value added activities (Rasiah, 2008; Giroud, 2003). Local firms are mostly comprised of big conglomerate groups in most manufacturing activities. These conglomerates are successful but to date have been heavily subsidized by the government, often to the detriment of real managerial and technical capability development. Small firms have not developed equally well and, although there are efforts to support them and make them competitive, these efforts are yet to bear fruits. The lack of focus on utilizing the organizations that were created to support upgrading, along with the lack of performance appraisal of their management, has resulted in a lack of support for the industrial and complementary firms in Malaysia (Rasiah, 2008). The tight labor market made the government allow foreign workers to be hired in the manufacturing industries. This has slowed upgrading down. More importantly, the government did not have a clear technology development policy that focused on supporting catching up among local firms (Rasiah, 2008).

By the end of the Second Industrial Master Plan the government had already realized the weakness, and noted that the economy did not meet the targets as expected. The economy grew at 4.6 per cent per annum for the period 1996-2005, falling short of the forecasted 7.9 per cent. All sectors missed their growth targets, except mining and quarrying, which expanded 2.5 per cent; above the 1.9 target. The faster than expected growth was attributed to the development of the oil and gas industry (MITI, 2006). To address these weaknesses the government launched the Third Industrial Master Plan (IMP3), which outlined the steps that Malaysia intended to take from 2006 to 2020, in line with the Vision 2020, launched in 1991, in which Malaysia envisaged its transformation into a developed nation.

I.7. Towards Global Competitiveness

The government of Malaysia is determined to steer the country to achieve the status of a fully developed nation by 2020. Toward this end a new industrialization strategy was launched in 2006, stressing the importance of the service sector as the vehicle through which this vision is to be realized. This was a complete departure from the development strategy previously used, where the manufacturing sector was the main driver for industrialization. The government continued to apply selective policies targeting the sectors intended to be developed, and at the same time relying on foreign firms. The world economic crisis of2008 led to a slow down in its growth, but the Malaysian economy is already exhibiting signs of recovery. It is hoped that, with the economy recovering, domestic industries will continue to develop and become competitive, although most of them enjoy government subsidies. Due to its improved and favorable location factors, Malaysia is predetermined to be a major destination for FDI in the near future, and it is on the path to become an industrialized country, in spite of operating in a globally competitive environment.

The IMP3 is a 15 year blue print for industrial development in Malaysia. It is expected to drive industrialization towards a higher level of global competitiveness, emphasizing transformation and innovation in the manufacturing and service sectors, in an integrated manner, towards attaining the developed nation status under Vision 2020. The key strategies of imp3 are built on five strategic thrusts of the National mission, introduced in the 9th master plan. In this regard, a total of ten strategic thrusts were outlined to assist in the achievement of the macro targets, and were classified in three broad categories, namely development initiatives, which include enhancing Malaysia's position as a major trading nation and generating investment in target areas, among others; promotion of growth areas, which include sustaining manufacturing and promoting services as the main sector; the last category entails enhancing the enabling environment, which includes facilitating the development of knowledge intensive technologies and developing innovative and creative human capital (MITI, 2006).

The government identified 12 target growth industries in the manufacturing sector as well as eight service sectors for further development and promotion, given that these industries are strategically important for contributing to a greater growth of the manufacturing sector, as well as for export and to strengthen sectoral-linkages (table 2). While the manufacturing sector was targeted to take the lead in driving growth under IMP2, IMP3 sees the service sector assuming the leading role in driving economic growth between 2006 and 2020. It also anticipated that all sectors, except services, were going to see a decline in their contribution to GDP by 2020. As a result, the Malaysian economy is expected to grow at an average rate of 6.3 per cent during this period (MITI, 2006).

The manufacturing sector has been declining since 1995. Its average annual growth fell from 11.7 per cent in 1990-1994 to 5.9 per cent in 19951999 and to 4.8 per cent in 2000-2005. The contribution of manufacturing to GDP, which had risen from 24.6 per cent in 1990 to 30.9 per cent in 2000, fell gradually to 30.1 per cent in 2007. The growth rate of its share in total employment has moderated considerably. It only managed to increase its share in 2000-2007 by a simple 1.3 points, to 28.9 per cent. Unless institutional change helps drive an upgrading, the manufacturing sector in Malaysia is expected to contract further. These results suggest that Malaysia could negatively be de-industrializing. This is because the Malaysian manufacturing sector continues to be affected by rising production costs, derived from a tightening labor market and cheap exports from China and Vietnam. This Malaysian sector has also failed to make a transition to higher value activities (Rasiah, 2008).

Although Malaysia has been affected by the 2008 world economic crisis, the effects are not severe compared to the Asian 1997-1998 crisis, and there are already signs of the sector bouncing back, especially in the chemical and the electrical and electronic industries. The country's financial system is strong and resilient, and able to support business growth, despite the weakening external environment. There were signs of positive growth in the fourth quarter of 2009. Even though, Malaysia's exports registered a significant contraction in the first quarter of the year; the domestic demand, on the other hand, continued to grow, increasing to 53 per cent from 43 per cent before, thus reducing the impact of the slower global demand. The measures being taken include encouraging Malaysian entrepreneurs who have successfully built up businesses overseas to return home to develop their operations, given that the country is less affected by the economic downturn and remains an attractive location for business. MIDA has a pack of incentives to assist in this (MIDA, 2009).

Foreign investors continued to find Malaysia an attractive destination for investments, particularly in the manufacturing sector, with the country recording a double-digit increase (38%) in approved FDI, amounting to RM 46.1 billion (or 73.4%) in 2008 from RM 33.4 billion in 2007. This represented the fifth consecutive year of growth in FDI, with RM 20.2 billion in 2006, RM 17.9 billion in 2005 and RM 13.1 billion in 2004, reflecting foreign investors' confidence that Malaysia remained a preferred location for business operations. Existing foreign investors continued to reinvest and expand their operations in Malaysia, especially into higher value added products. In 2008, foreign investments in expansion/diversification projects amounted to RM 11.9 billion, of which the e&e industry accounted for RM 6.48 billion. Investments in the sector in 2008 were the highest recorded to date, and more than doubled the target of RM 27.5 billion per annum set under IMP 3. Thus, it is too early to think about de-industrializing, as Malaysia seems to have put measures in place to move to the next level (MIDA, 2009).

Malaysia has also been able to comply with WTO requirements, especially in the export oriented industry; hence, the current WTO commitment does not seem to have hindered its development so far. The challenge lies in the import substitution sector, which has continued to enjoy the government's protection, especially in the automobile sector, where the nominal tariff for complete built up units can range between 140 and 300 per cent. In this sub-sector, protection has enabled both national car producers (Proton and Perodua) to capture up to 93 per cent of the domestic market. Furthermore, local content requirements have created about 220 vendors that are component suppliers, of which 40 are regarded to have export capability (Yean, 2004). With China being a member of WTO there is a greater opportunity for Malaysia, but also increased competition. With more liberalization in trade and investment, more and more policy instruments will be included in the WTO disciplines. This means that there will be a reduction in the policy instruments that can be utilized for industrial policy that is generally available for countries pursuing industrialization. Thus, the immediate challenge for industrialization is to use WTO consistent policy to industrialize.

II. What are the Lessons?

The road to industrial success has certainly not been smooth for Malaysia. Based on the above discussion we can derive the following lessons.

The role of government is very important in the development process. In Malaysia, the government provided first and foremost the infrastructure that was required at the different stages of development to include roads, ports, railways, airports and heavy investment in information communication and technologies (ICT), and this has caused Malaysia to remain an attractive destination for foreign firms. Secondly, the government developed its labor force which became competent to work in industry. Once the labor market became tight, the government was flexible enough to allow foreign workers to enter the job market. Thirdly, the government created incentives, subsidies and even tariffs at the different stages of development, based on the needs of the time, and was willing to change course once the strategies did not work. Fourthly, the government was instrumental in maintaining a stable macroeconomic environment to avoid balance of payment problems caused by outflows of capital. The government was instrumental in selecting the sectors that were considered important for development, and selective policies have been pursued targeting those sectors. Thus, without government intervention at various stages it would have been extremely difficult for Malaysia to industrialize.

Foreign firms can play an important role in development. In Malaysia they have not only assisted in addressing balance of payment problems, but also in boosting the manufacturing sector through the production of goods for export. They assisted in the creation of employment, increased output, transfer of technology and established some linkages with local firms. Foreign firms involved at the initial stages of production tend to be labor intensive, but as they move up the value chain they demand more skilled labor and infrastructure. Using the Malaysian experience one gets the feeling that the country has not been able to get the most out of these foreign firms. This is mainly due to the fact that foreign firms have not always assisted in the development of local firms, and therefore SMES are not as competitive. This seems to have been a policy failure at the early stages of industrialization. With incentives from the government, some foreign firms have begun transferring technology to local firms. Hence, it may be a matter of time before Malaysia begins enjoying the benefits. It is also important to note that Malaysia mainly attracted foreign firms in selected industries, based on comparative advantage.

Closely linked to the role of government are institutions. The government in Malaysia established many institutions that were supposed to facilitate industrialization. These institutions have worked very closely with both local and foreign firms, offering different incentives and support through initiatives like hand holding, among others. These institutions have evolved over time to be able to serve the firms better. Malaysia's institutions have a clear mandate and adequate funding. In an environment with many institutions, coordination is paramount, which however has not always been the case.

Lastly, the Malaysian government, with good institutions, has been able to use foreign firms in all its sectors, but most notably in the manufacturing sector and more recently in the service sector to spearhead development. Foreign firms, in their pursuit of profits, will only undertake activities that guarantee their success. Governments, on the other hand, have a responsibility of ensuring that they reap the benefits arising from the presence of foreign firms through the provision of incentives that allow for the creation of local linkages and the development of domestic industries. Good institutions will endeavor to address the challenges that foreign firms face, and through incentives can become useful links by which local firms can benefit. In as much as foreign firms have made Malaysia very susceptible to external conditions, there is overwhelming evidence that even under such circumstances the country has achieved great success worth emulating by other developing countries.

III. Conclusion

This paper discusses industrialization in Malaysia focusing on the dynamic role of the government and foreign firms. Foreign firms have a long history in Malaysia. The Malaysian government has been able not only to create a conducive environment for them to thrive, but also to benefit the country through employment creation and technology transfer, among other benefits. Without the intervention of government, it is doubtful that Malaysia could have achieved much benefit. Institutions can also perform an important role in becoming vehicles through which the government interacts with foreign firms. Malaysia has pursued both export and import industrialization strategies, with mixed results. Insofar as market oriented policies can be preferred as a development strategy, governments ought to pursue policies that can support the development of local industries, by ensuring that they benefit from foreign firms' spillovers; something that markets cannot guarantee. The shift from manufacturing to services as a driver for economic growth in Malaysia suggests the dawn of a new era in industrialization.

References

Aitken, B., G. Hanson and A. Harrison (1997), "Spillovers, Foreign Investment and Export Behaviour", Journal of International Economics, 43, pp. 103-132. [ Links ]

Alavi, R. (1996), Industrializing in Malaysia: Import Substitution and Infant Industry Performance, Routledge. [ Links ]

Athukorala, C. P. and J. Menon (1996), "Export-led Industrialization, Employment and Equity: The Malaysian Case", Departmental Working Papers no. 5, Australian National University, Economics RSPAS. [ Links ]

Blonigen, A. B. (2005), "A Review of the Empirical Literature on FDI Determinants, NBER Working Papers no. 11299, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [ Links ]

Blumenfeld, J. (1991), Economic Interdependence in Southern Africa: From Conflict to Cooperation? London, Pinter Publishers. [ Links ]

Crouch, H. (2001), "Managing Ethnic Tensions through Affirmative Action: The Malaysian Experience", in N. J. Colletta, T. G. Lim and A. Kelles-Viitanen (eds.), Social Cohesion and Conflict Prevention in Asia, Washington, D. C., The World Bank, pp. 225-262. [ Links ]

Dos Santos, T. (1970), "The Structure of Dependency", The American Economic Review, 60 (2), pp. 231-236. [ Links ]

Drabble, H. J. (2000), An Economic History of Malaysia, c. 1800-1900: The Transition to Modern Economic Growth, St. Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Giroud, A. (2003), Transnational Corporations, Technology and Economic Development: Backward Linkages and Knowledge Transfer in SouthEast Asia, Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Jomo, K. S. (1993), "Introduction", in Jomo K. S. (ed.), Industrialising Malaysia: Policy, Performance, Prospects, Routledge. [ Links ]