Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Política y gobierno

versión impresa ISSN 1665-2037

Polít. gob vol.27 no.2 Ciudad de México jul./dic. 2020 Epub 17-Feb-2021

Research Notes

Did Religious Voters Turn to AMLO in 2018? An Empirical Analysis

1Profesor en el Tecnológico de Monterrey. Eugenio Garza Lagüera y Rufino Tamayo, San Pedro Garza García, 66269, Nuevo León. Tel: 52 818625 8300, ext. 6376. Correo-e: alejandrod.dominguez@tec.mx.

Morena, a new left-wing party which supports income redistribution, and at the same time, appeals to values in a generic sense, has attracted many religious voters. Drawing from the literature on religion and politics in Latin America, and analyzing the 2018 CNEP surveys conducted in Mexico, available evidence suggests that observant and traditionalist Catholics were more likely to support AMLO, whereas Protestants and Evangelicals were less likely to vote for him, arguably due to the vague stance that Morena has taken regarding moral values. Thus, the broader coalition that cemented AMLO’s victory seems to be composed of secularists, who still favor the left, and observant Catholics.

Keywords: Catholic; religion; Morena; left; Mexico

Morena, un nuevo partido de izquierda que apoya la redistribución del ingreso y, al mismo tiempo, apela a valores morales en un sentido genérico, ha atraído a muchos votantes religiosos. A partir de la literatura sobre religión y política en América Latina y con datos de la encuesta del Proyecto Comparado de Elecciones Nacionales (CNEP, por sus siglas en inglés) de 2018 realizada en México, este trabajo muestra que los católicos observantes y tradicionalistas votaron por AMLO con mayor probabilidad que la ciudadanía sin adscripción religiosa, mientras que los protestantes y evangélicos votaron por él con menor probabilidad, posiblemente debido a la vaga postura que Morena ha adoptado respecto a valores morales. Así, la amplia coalición que cimentó la victoria de AMLO parece estar compuesta por secularistas, que aún favorecen a la izquierda, y católicos observantes.

Palabras clave: catolicismo; religión; Morena; izquierda; México

Left-wing candidates rarely attract religious vote because they push for liberal moral values that are usually inimical for religious citizens. Despite this, the 2018 election showed a striking convergence between the left-wing candidate, AMLO, and Catholic religious citizens. How can we account for this convergence? Are religious voters driven by candidates’ religious discourse in a generic sense, beyond the divide among Catholics, Protestants, and Evangelicals?

In order to offer valuable insights to these questions, scholars have explored the role that religion plays on Mexico’s party system. It is true that Mexican politics was largely dominated for a single party at the national level, but nowadays, the country faces debates on religiosity and moral issues that could trigger a religious vote among different political options. Mexico could be considered as a religious country, in which eight out of ten are Catholics (INEGI, 2010), with one third of Catholics and 60 per cent of Protestants and Evangelicals attending church services every week (CNEP, 2018), and only 10 per cent not belonging to any church.

On Mexico’s religious cleavages, the usual milestones are the 19th century Church-State disputes, and the Cristero rebellion of 1926 (Meyer, 1979). In partisan politics, during the last thirty years, religion has been analyzed through political parties’ supporters. For example, the National Action Party (PAN)’s profile usually includes its Catholic baggage, formal ties to the international Christian Democrat movement, and a strong opposition to deregulation of abortion, and State sanctioned same sex marriage (Mabry, 1973; Magaloni and Moreno, 2003).

Regarding the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), analysts have highlighted its religious traditionalism, its recognition of legal status to churches (Lamadrid, 1994; Gill, 1999), and its continuous political appeals to Catholic bishops prompted by Cárdenas in the 1930s (Muro González, 1994), Salinas in the 1990s (Monsiváis, 1992), and Peña Nieto in the 2010s (Barranco, 2018), as well as some connections with some specific Evangelical churches (De la Torre, 1996; Barracca and Howell, 2014; Garma, 2019).

In contrast, the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) at the national level heralded liberal policies such as clergy voting rights, gay marriage and deregulation of abortion (Monsiváis, 1992; Magaloni and Moreno, 2003; Camp, 2008). There are reasons to believe that this party position is also spread across Mexico, as revealed by the positive impact of state governors affiliated with the PRD on state level recognition of same sex relationship rights (Beer and Cruz-Aceves, 2018: 19) .

This party system, in place for more than two decades, has come to an end with the strong emergence of Morena (originally Movimiento Regeneración Nacional or National Regeneration Movement, a new political party that received official registry on July of 2014), which has championed support for the poor, promised to fight corruption, cut bureaucratic privileges and useless spending to reallocate resources on social welfare programs. At the same time, Morena sent an ambivalent and vague policy message towards abortion and gay rights. As I suggest in this research note, this strategy, deliberated or unconscious, seems to have succeeded at attracting religious voters (Díaz Domínguez, 2019).

Theoretical framework

In some democracies, party competition is usually studied through the structural bases of parties’ support, such as political divisions or cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan, 1967, 1990), in which religious conflicts between Catholic and Protestant electorates, and between confessional and secular ones, could translate into the party system, such as it has been took place in several Latin America countries (Hagopian, 2009; Freston, 2009; Boas and Smith, 2015; Lindhardt and Thorsen, 2015; Ruiz, 2015; Althoff, 2019).

In Latin America, on the one and, religion has influenced electoral competition when moral issues have become controversial, such as divorce during the 1990s in Chile (Lies and Malone, 2006), same sex marriage across Latin American countries during the 2000s (Lodola and Corral, 2013: 44-45), and moral traditionalism in Brazil (Smith, 2019). On the other hand, Catholic communities aligned with liberation theology’s doctrine do encourage political participation, and even root for leftist parties (Parker, 2016; Díaz Domínguez, 2013). Nevertheless, traditional distinctions between the political effects of the Catholic liberation theology and the Pentecostal prosperity gospel in Latin America are challenged because of Mexican and Brazilian Pentecostal sympathies toward a liberationist agenda, which is mainly based on social justice demands (Chaves, 2015; Garma, 2019).

In transitional states, Protestant churches could exercise a more positive impact on democratic development, and civil society pluralism. This is arguably due to the mainline Protestant ethos, which distinguishes between public and private spheres (Tusalem, 2009; Woodberry, 2012). Historically, mainline Protestantism and its theological traditions, such as the social gospel, were more favorable to participation in public affairs than Pentecostalism, which preaches a pre-millennial theology and strict separation of the spiritual realm and worldly affairs (Althoff, 2019). Neo-Pentecostalism and post-millennial theology however have challenged this position, as Neo-Pentecostal churches are thrusting themselves enthusiastically into politics. Thus, there are reasons to believe that some non-Catholic churches could be interested in political affairs and elections (Telles et al., 2014; Smith, 2019; Sarmet and Belchior, 2016).

Political activism of Pentecostals in Chile and Brazil (Lindhardt and Thorsen, 2015) and in Guatemala and Brazil (Freston, 2009) suggest that specific Evangelical churches are exercising a greater political impact today. For instance, politics and religion played an important role in the 2014 Brazil’s presidential elections, in which Catholic bishops preached against Dilma Rousseff, whereas the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG) endorsed her (Smith, 2019). However, there were subtler differences when analyzing legislative elections. For example, Brazilian Pentecostals were more likely to vote for Pentecostal candidates when compared to Evangelicals for their own candidates, and these differences disappeared between Pentecostals and members of the UCKG regarding support for their own candidates (Lacerda, 2018).

Although Pentecostals and neo-Pentecostals may differ in when Christ will return on earth, translating into pre and post-millennialism, in practice some Pentecostal churches in Guatemala and Mexico are teaching a post-millennialist doctrine, increasing the likelihood to engage in politics (Althoff, 2019; Garma, 2019). Thus, there is a sort of revival on the political impact of religions in Latin America. In this way, predictions of modernization theorists that anticipated the fading of religion in politics have not fully explained why religious divisions are still relevant in politics (Norris and Inglehart, 2004; Bucley, 2016).

Nevertheless, the impact of religion on politics requires a cautionary note. Religious commitment mainly relates to moral and cultural issues, such as abortion and gay rights across religious affiliations. Regarding social welfare, tax policies or international affairs however, the link between religion and politics is weaker or hard to establish (Campbell, Layman and Green, 2016: 235). These findings remind us that the effects of religion may be limited to specific policy domains.

In Mexico, Catholics have supported the three main political parties: the PAN, due to its conservatism and fight for democracy (Klesner, 1987, Magaloni and Moreno, 2003; Chand, 2001; Moreno, 2009: 279); the PRI, when looking for a strong leader (Magaloni and Moreno, 2003; Hagopian, 2009); and the PRD, for its social welfare policies at the local level (Muro González, 1994).

Regarding Protestants and Evangelicals in Mexico, although some denominations remain politically aloof, such as Latter-Day Saints, and Jehovah Witnesses (Fortuny, 1996), several case studies suggest that some Evangelical affiliations (such as the Light of the World Church) supported the PRI (De la Torre, 1996: 160; Monsiváis, 1992: 166-167). One of the reasons is that religious minorities are less likely to support the PAN, as long as they associate this party with the Catholic church. Thus, in order to preserve the secular State, they prefer to vote for the PRI (Barracca and Howell, 2014: 24). In contrast, other case studies suggest that religious Protestants and Evangelicals supported the PRD in places in which the government was not paying attention to economic inequalities and poverty (Fortuny, 1996).

There are two arguments that explain why a plurality of Evangelicals would prefer the PRI. To begin with, because of its history of Evangelical persecution, they prefer a party which offers some official protection, and that’s why they celebrate President Juárez day, who championed Church-State separation in Mexico (Garma, 2019: 39). Secondly, the PRI has maintained a conservative position on social issues, which tunes in well to Evangelicals, who are more socially conservative than the general population (Barracca and Howell, 2014: 34, 41). One exemption though is the House of the Rock, a neo-Pentecostal church with ties to the PAN in Mexico City (Garma, 2019).

In relation to religious dimensions, such as attendance to religious services, data from the Comparative Study on Electoral Systems (CSES) reported that in 37 presidential and parliamentary elections in 32 countries during the 1990s, “almost threequarters of the most devout (defined as those who reported attending religious services at least once per week) voted for parties of the right. By contrast, among the least religious, those who never attended religious services, less than half (45 %) voted for the right” (Norris and Inglehart, 2004: 201).

This comparative evidence seems to fit into the Mexican case. During the mid-1980s, PAN’s electorate were more religious (Camp, 1997: 56), and during the 2000, and 2006 presidential elections, the PAN did very well within those who gave more importance to religion and attended more to church (Moreno, 2009: 284). This support however did not translate into a religiously oriented right-wing party, because the PAN built a broader coalition to defeat the PRI (Magaloni and Moreno, 2003). In fact, religious citizens were more likely to vote and believe in political change (Moreno and Mendizábal, 2015: 313).

Regarding the PRI, church attendance increased vote choice during the 1988 presidential, and the 1991 midterm elections (Domínguez and McCann, 1996: 104, 138). Church attendance also reinforced support for the PRI during the 1994 presidential elections, and the 1997 midterm elections, particularly among citizens with low levels of political awareness (Moreno, 1999: 141).

In 2012, Catholics preferred PRI’s candidate, Enrique Peña Nieto, when compared to the PRD’s candidate, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (popularly known as AMLO) (Díaz Domínguez, 2014: 51). The effect of religiosity in the 2012 presidential elections was also negative for the PRD’s candidate, elections in which the PRI received a great deal of support among weekly church goers (Díaz Domínguez, 2014: 55; Torcal, 2014: 115). Finally, in 2015, there is evidence through spatial analysis that more Catholics in the district were negatively correlated with vote for Morena (Charles-Leija, Torres and Colima, 2018: 131).

All these academic studies and empirical evidence suggest that in general, religious voters prefer conservative political parties, whereas secular voters prefer liberal options (Norris and Inglehart, 2004; Hagopian, 2009). The question here is whether religious voters could be eventually attracted by a liberal political option. The preliminary answer depends on whether a liberal/leftist candidate can successfully attract religious voters when embracing a sort of religious discourse.

Preliminary survey evidence suggests that this could be the case for the last Mexico’s elections. The polling firm ARCOP in June of 2018 found that Catholics and Evangelicals preferred AMLO when compared to PRI’s candidate, José Antonio Meade, who was mainly preferred by respondents who did not belong to any church, also called “secularists” (for a theoretical characterization see Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme, 2017). Berumen-ipsos surveys in May of 2018 showed Evangelical support for Morena’s candidate, and Catholic support for the PRI’s candidate. Finally, the 2018 CNEP post-electoral surveys showed large Catholic support for López Obrador, but this pattern did not hold for Evangelicals.

All these pieces of preliminary evidence suggest a noteworthy change: religious factors played a different role in Mexico’s 2018 presidential elections. Preliminary evidence suggests a positive impact of religiosity among Catholics on support for Morena (Díaz Domínguez, 2019). In twelve years, López Obrador went from receiving secularists’ support in 2006 as a candidate for the PRD (Camp, 2008) to attract Catholic religious voters in 2018, when running for Morena. Catholic Church attendance, this time, definitively increased popular support for AMLO. This a noticeable change that deserves additional theoretical elaboration and further empirical verification.

There are three main factors that could explain why religious voters decided to support a leftist presidential candidate: a) previous experiences at the local level suggested a sort of association between religious variables and support for the left; b) preferences for political leaders who hold religious principles were channeled through the left; and c) a religious discourse in a generic sense that could attract religious voters. An alternate formulation could be left-wing candidates can attract religious voters if: a) they emphasize welfare issues that may be relevant for religious citizens (when they come from the poorer backgrounds); b) they downplay moral issues that may be divisive for conservative religious voters; and c) they highlight moral doctrines that may be closer to leftwing values.

The Mexican left has shown some ability to connect with the religious voters in the past, such as the Mexican Communist Party support for clergy’s voting rights during the 1977 electoral reform (Monsiváis, 1992), and the campaign to encourage Catholics to vote for left-wing presidential candidates during the 1982 and 1988 elections (Camp, 1997).1 Other sources of leftist popular support were linked to demands for social welfare programs, in line with the Catholic Social Doctrine. Some Mexican bishops during the 1980s and 1990s at the local level emphasized through public statements and pastoral letters a political agenda composed of social justice, participation, and free and fair elections (García, 1999; Soriano, 1999; Chand, 2001; Trejo, 2009). These calls arguably induced sympathies for the left among Catholics (Hale, 2015).

Regarding preferences for political leaders who hold religious principles, most Mexicans separate religious beliefs from public values that are essential for leadership. Approximately, two-thirds prefer to maintain a secular regime, whereas one-third prefers leaders with religious principles (Camp, 2008). This segment of the electorate, who demands religious interventions in public life, has been analyzed considering different contexts. In countries in which citizens belonging to religious majorities do not attend church on frequent basis, leaders with religious principles are usually preferred, whereas countries in which individuals who belong to religious minorities are less likely to prefer such a type of leadership (Buckley, 2016).

In the 2018 presidential elections, Mexicans who demanded religious interventions in public life and regularly attend church seem to have supported López Obrador. This effect was arguably due to AMLO’ strategy to get into the religious sensibilities of the people (Lee, 2018). He often spoke of faith and values, holding off on promoting same-sex marriage and decriminalizing abortion, typically avoiding explicit mentions, or just saying that these topics could be decided by referendum.

The idea of making continuous appeals to traditional and religious values was an attempt to soften a radical image after accusations from opponents in previous elections (Agreen, 2018). AMLO’s continues religious references emphasize his interpretation of Christian love, which he equalizes to justice, and his previous campaign mottos: “Light of hope” in 2006, and “Republic of love” in 2012, they reveal a religious initial pattern (Garma, 2019: 43; Barranco, 2018).

Connecting all these three arguments, it seems plausible to argue that López Obrador, a popular candidate after two presidential campaigns (he got 35.31 per cent in 2006, and 31.6 per cent in 2012), was in search of additional points to reach the presidency. Thus, one reservoir of support was the religious vote, given that Mexico’s religious voters are more likely to support political change (Moreno, 2003: 174).

To attract these voters, AMLO offered a message on abstract values. For instance, when López Obrador proposed a “moral constitution” at the beginning of the electoral campaign, 73 per cent supported this abstract idea: “Mexico does need a moral guidance, through something like a moral constitution”, as reported by a survey published in the newspaper El Financiero (Moreno, 2018 a).2 Finally, López Obrador ran in alliance with the Social Encounter Party (PES), a party with ties to Evangelical churches. 3

Although in Morena and its left-wing ally, PT’s manifestos gender equity entailed affirmative action policies, the PES sought to protect life since conception, marriage between male and female only, and the creation of the National Minister of the Family. In addition, López Obrador just devoted one out of 209 public events to gender issues: social welfare for single young mothers who attended college in the state of Nuevo León (Morales and Palma, 2019: 51). In relation to abortion and same sex marriage, Morena’s presidential candidate limited himself to repeat that “these are topics in which citizens have the last word” (Garma, 2019: 42). Even women in charge of different campaign issues within the party avoided abortion to not confront López Obrador (Morales and Palma, 2019: 52).

In addition to religious factors, it is important to mention other causes of the 2018 electoral results, such as critiques about PRI’s performance in office (see other articles in this issue). Frequent scandals about corruption and human rights violations during Peña Nieto’s administration fueled popular discontent (Mattiace, 2019: 286-287). Thus, AMLO’s platform was committed to capture the disaffected voter: on the economic side, by promising income redistribution instead of more free market policies, and on the political side, by promising deliberation, peace, less corruption, and political change (Moreno, 2018 b: 73 ; Mattiace, 2019: 295-297).

Hypotheses, data, and methods

From the literature review, standard hypotheses emerge, such as citizens who frequently attend Church and hold the highest scores on traditional moral values will be more likely to vote for the PAN and the PRI; Catholics will be more likely to vote for the PAN and the PRI; Protestants and Evangelicals will be more likely to vote for the PRI; and citizens who prefer leaders with religious principles will be more likely to vote for the PAN.

Nevertheless, based on a revisited theory, there are reasons to believe that Catholic Church goers, and those who prefer leaders with religious principles will be more inclined to support Morena. These last assumptions however run against what standard theories suggests, due to the novel electoral effect of religious variables on support for the left in Mexico.

In this way, standard hypotheses need to be revised through the light of a previous revisited theory: testing whether AMLO’s efforts to attract a portion of the religious vote were successful. In other words: Catholics who frequently attend Church and hold the highest scores on traditional moral values are more likely to support Morena, due to religious appeals made by AMLO and his vague messages on abortion and gay rights.

Protestants and Evangelicals will be more likely to favor a wait-and-see strategy, due to competing factors: a) the alliance between PES (a party with Evangelical ties) and Morena would encourage support for AMLO, but b) vague AMLO’s messages on moral values would rise concerns among Evangelicals, given their fierce opposition to abortion and gay rights. Thus, expectations about Protestants and Evangelicals are mixed. Finally, citizens who prefer leaders with religious principles will be more likely to vote for Morena, due to AMLO’s religious appeals.

Thus, candidate’s religious appeals in a generic sense could attract religious voters, but electoral success would depend on to what extent religious voters need to hear the specifics of policies, such as on moral values. Those who saw a radicalized AMLO in 2006 and 2012 may still have voted for Morena in 2018 as long as they had noticed a more non-committal candidate on these issues. On the contrary, those who saw a vague candidate on moral values in 2018, they may have gone for different political options.

Data for the analysis come from the 2018 CNEP post electoral survey, a face to face and nationally representative poll conducted between 12 and 22 of July, among 1 428 Mexican citizens in 84 primary sampling points. Margin of error was +/- 2.6 points, a 95 per cent confidence level, and refusal rate of 48 per cent. Descriptive statistics of the analyzed data are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Valid (%) | Mean | Standard deviations | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 100.00 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| AMLO 12 | 100.00 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| AMLO 18 | 100.00 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| EPN 12 | 100.00 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

| JAM 18 | 100.00 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 |

| JVM 12 | 100.00 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 |

| RAC 18 | 100.00 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| Catholic | 100.00 | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Protestant -Evangelical | 100.00 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| Secularist | 100.00 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 |

| Church attendance | 99.37 | 3.34 | 1.50 | 1 | 5 |

| Religious leader | 98.04 | 2.21 | 1.21 | 1 | 5 |

| Moral values | 96.04 | 11.19 | 3.33 | 1 | 16 |

| Abortion* | 96.64 | 2.91 | 0.97 | 1 | 4 |

| Gay adoption* | 96.85 | 2.97 | 1.01 | 1 | 4 |

| Gay marriage* | 96.15 | 2.61 | 1.05 | 1 | 4 |

| Marijuana * | 98.11 | 3.01 | 0.97 | 1 | 4 |

| Married | 100.00 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 100.00 | 3.60 | 1.67 | 1 | 6 |

| Education | 99.86 | 4.84 | 1.95 | 1 | 9 |

| Income | 90.20 | 2.88 | 1.92 | 1 | 9 |

| Interest in politics | 99.86 | 2.28 | 0.95 | 1 | 4 |

| North | 100.00 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| West | 100.00 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| South | 100.00 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| TV News | 100.00 | 3.82 | 1.48 | 1 | 5 |

| Urban | 100.00 | 2.52 | 0.76 | 1 | 3 |

| pid Morena | 100.00 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| pid PAN | 100.00 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| pid PRI | 100.00 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0 | 1 |

| Ideology | 78.36 | 5.22 | 2.82 | 1 | 10 |

Source: 2018 CNEP Mexico’ sample. *Part of the Moral Values additive index (alpha = 0.81). Data not available (%): abortion (3.36); church attendance (0.63); education (0.14); gay adoption (3.15); gay marriage (3.85); income (9.8); ideology (21.64); marijuana (1.89); and prefers leader with religious inclinations (1.96).

Statistical analyses are based on multinomial logistic regressions, in which the dependent variable is a vote choice set comprised of José Antonio Meade (JAM), who ran for the coalition PRI-PVEM-NA; Ricardo Anaya Cortés (RAC), who ran for the coalition PAN-PRD-MC; other options (independent candidates, such as Jaime Rodríguez “el Bronco” or Margarita Zavala, who finally declined few weeks before the election day, or any other voting decision), and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) who ran for the coalition Morena-PT-PES, who serves as a reference category.4

Main variables of interest are religious affiliations, such as dummy variables for Catholics, and Protestants/Evangelicals, in which no affiliation serves as reference category. Due to the reduced number of cases, Protestants and Evangelicals were grouped. There are three additional religious dimensions: a) Church attendance as a measure of religiosity, from almost never to weekly attendance; b) Support for leaders with religious principles as a measure of religion intervention on public domain (B.ReligRule), from strongly disagreement to strongly agreement; and c) a moral values additive index, comprised of abortion, gay marriage, gay adoption, and marijuana (alpha=0.81), as a measure of traditionalism, which ranges from total support to total rejection.

A set of covariates serves as control variables: female, age, income, education, urban, civil status (a dummy variable for married), TV news consumption, regional dummy variables, such as North, South, and West, in which the Central region serves as reference category, ideology, measured as self-placement on the left-right continuum, vote choice in 2012 as dummy variables for the PAN (Josefina Vázquez Mota-JVM), the PRI (Enrique Peña Nieto-EPN), and the PRD (AMLO), interest in politics, and finally, dummy variables for party identification with the PAN, the PRI, and Morena (Moreno, 2018b; Morales, 2016).

Results and discussion

Tables 2 and 3 report six models. Table 2 shows base models, and 3 includes interactive models. In Table 2, there are four base models, which show the effects of religious factors in a separate way. The first model shows all the control variables plus religious affiliations, that is, Catholics and Protestants/Evangelicals. The second model shows all the model 1 variables plus Church attendance; the third one shows model 1 plus moral values, and the last one shows model 1 plus leaders with religious principles. Thus, models 2, 3, and 4 essentially are trying to test the isolated effects of attendance, moral values, and leaders with religious principles on vote choice, keeping all control variables and religious affiliations into the equation.

TABLE 2 Determinants of voting in mexico’s presidential elections, 2018 (base models)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | JAM | Others | RAC | JAM | Others | RAC | JAM | Others | RAC | JAM | Others | RAC |

| Female | 0.45 | -0.14 | 0.05 | 0.49* | -0.09 | 0.05 | 0.41 | -0.15 | 0.05 | 0.45 | -0.14 | 0.02 |

| (0.29) | (0.17) | (0.26) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.26) | (0.29) | (0.17) | (0.26) | (0.29) | (0.17) | (0.26) | |

| AMLO 12 | -2.32** | -1.68** | -1.76** | -2.41** | -1.76** | -1.78** | -2.28** | -1.71** | -1.77** | -2.31** | -1.70** | -1.85** |

| (0.80) | (0.28) | (0.56) | (0.81) | (0.28) | (0.56) | (0.80) | (0.28) | (0.56) | (0.80) | (0.28) | (0.56) | |

| JVM 12 | -0.09 | -0.39 | 1.13** | -0.11 | -0.41 | 1.14** | -0.08 | -0.39 | 1.13** | -0.06 | -0.40 | 1.06** |

| (0.51) | (0.28) | (0.34) | (0.52) | (0.28) | (0.34) | (0.52) | (0.28) | (0.34) | (0.52) | (0.28) | (0.34) | |

| EPN 12 | 0.60* | -1.02** | -0.38 | 0.65* | -1.02** | -0.38 | 0.61* | -1.05** | -0.41 | 0.58* | -1.05** | -0.42 |

| (0.35) | (0.24) | (0.36) | (0.35) | (0.24) | (0.36) | (0.35) | (0.24) | (0.36) | (0.35) | (0.24) | (0.36) | |

| Married | -0.52* | -0.40** | -0.28 | -0.52* | -0.37** | -0.29 | -0.48 | -0.38** | -0.28 | -0.52* | -0.40** | -0.26 |

| (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.27) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.27) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.27) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.28) | |

| PID PRI | 2.99** | 0.66* | 0.63 | 3.03** | 0.70* | 0.65 | 3.03** | 0.69* | 0.59 | 3.00** | 0.69* | 0.49 |

| (0.40) | (0.39) | (0.51) | (0.41) | (0.40) | (0.51) | (0.41) | (0.40) | (0.51) | (0.41) | (0.40) | (0.54) | |

| PID PAN | 0.73 | 1.31** | 3.67** | 0.68 | 1.32** | 3.67** | 0.76 | 1.32** | 3.68** | 0.78 | 1.35** | 3.67** |

| (1.17) | (0.66) | (0.60) | (1.18) | (0.66) | (0.60) | (1.17) | (0.66) | (0.60) | (1.17) | (0.66) | (0.60) | |

| PID Morena | -1.71** | -1.28** | -2.75** | -1.74** | -1.31** | -2.76** | -1.69** | -1.25** | -2.75** | -1.70** | -1.26** | -2.75** |

| (0.62) | (0.23) | (0.73) | (0.62) | (0.24) | (0.73) | (0.62) | (0.23) | (0.73) | (0.62) | (0.23) | (0.73) | |

| Ideology | 0.16** | 0.06* | 0.15** | 0.15** | 0.06 | 0.15** | 0.16** | 0.06* | 0.15** | 0.15** | 0.06* | 0.16** |

| (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Education | -0.05 | -0.08 | 0.00 | -0.04 | -0.06 | 0.01 | -0.05 | -0.08 | 0.00 | -0.07 | -0.10* | -0.03 |

| (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Income | -0.00 | 0.00 | -0.10 | -0.00 | 0.00 | -0.10 | -0.01 | -0.00 | -0.09 | -0.00 | -0.01 | -0.11 |

| (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | |

| Urban | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.14 | -0.04 | -0.06 | -0.13 | -0.05 | -0.05 | -0.13 | -0.02 | -0.05 | -0.15 |

| (0.20) | (0.12) | (0.17) | (0.21) | (0.12) | (0.17) | (0.21) | (0.12) | (0.17) | (0.20) | (0.12) | (0.17) | |

| Age | -0.07 | -0.07 | -0.07 | -0.03 | -0.04 | -0.07 | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.11 | -0.08 | -0.07 | -0.06 |

| (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| North | -0.38 | 0.12 | 0.25 | -0.39 | 0.14 | 0.24 | -0.39 | 0.15 | 0.29 | -0.38 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| (0.38) | (0.23) | (0.33) | (0.39) | (0.23) | (0.34) | (0.39) | (0.23) | (0.34) | (0.38) | (0.23) | (0.34) | |

| South | -1.06** | -0.59** | -0.74* | -1.14** | -0.61** | -0.75* | -1.07** | -0.61** | -0.73* | -1.01** | -0.55** | -0.76* |

| (0.44) | (0.25) | (0.41) | (0.44) | (0.25) | (0.41) | (0.44) | (0.25) | (0.41) | (0.44) | (0.25) | (0.42) | |

| West | -0.16 | 0.22 | 0.22 | -0.15 | 0.24 | 0.22 | -0.20 | 0.24 | 0.28 | -0.12 | 0.28 | 0.32 |

| (0.41) | (0.25) | (0.36) | (0.41) | (0.25) | (0.36) | (0.42) | (0.25) | (0.36) | (0.42) | (0.25) | (0.36) | |

| TV News | 0.13 | -0.04 | -0.12 | 0.12 | -0.05 | -0.12 | 0.14 | -0.05 | -0.13 | 0.12 | -0.04 | -0.11 |

| (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Interest pol. | -0.34** | -0.29** | -0.33** | -0.37** | -0.30** | -0.33** | -0.36** | -0.29** | -0.31** | -0.34** | -0.29** | -0.35** |

| (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | |

| Catholic | -0.46 | -0.03 | -0.08 | 0.12 | 0.28 | -0.10 | -0.47 | 0.04 | -0.08 | -0.42 | 0.00 | -0.06 |

| (0.51) | (0.31) | (0.49) | (0.57) | (0.34) | (0.54) | (0.51) | (0.31) | (0.48) | (0.51) | (0.31) | (0.49) | |

| Prot-Ev | -1.14 | 0.56 | 0.57 | -0.42 | 0.94** | 0.61 | -1.07 | 0.62 | 0.47 | -1.11 | 0.59 | 0.65 |

| (0.84) | (0.41) | (0.64) | (0.91) | (0.46) | (0.71) | (0.84) | (0.42) | (0.65) | (0.84) | (0.41) | (0.64) | |

| Attendance | -0.25** | -0.14** | 0.01 | |||||||||

| (0.12) | (0.07) | (0.10) | ||||||||||

| Moral values | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | ||||||||||

| Relig leader | -0.09 | -0.14* | -0.23** | |||||||||

| (0.12) | (0.07) | (0.11) | ||||||||||

| Intercept | -1.23 | 1.79** | 0.13 | -0.98 | 1.85** | 0.09 | -0.54 | 1.64** | -0.61 | -0.94 | 2.13** | 0.71 |

| (1.18) | (0.68) | (1.02) | (1.20) | (0.69) | (1.03) | (1.33) | (0.77) | (1.12) | (1.25) | (0.72) | (1.07) | |

| log Lik | -847.0 | -836.2 | -840.1 | -840.1 | ||||||||

| McFadden R2 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.46 | ||||||||

| Observations | 1 013 | 1 006 | 1 009 | 1 005 | ||||||||

Source: Multinomial logistic models, reference category vote for AMLO. 2018 CNEP Mexico’ sample. **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

TABLE 3 Determinants of voting in mexico’s presidential elections, 2018 (interactive models)

| (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | JAM | Others | RAC | JAM | Others | RAC | JAM | Others | RAC | JAM | Others | RAC |

| Female | 0.46 | -0.10 | 0.03 | 0.46 | -0.09 | 0.03 | 0.38 | -0.07 | 0.06 | 0.42 | -0.07 | 0.02 |

| (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.26) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.26) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.26) | (0.30) | (0.18) | (0.26) | |

| AMLO12 | -2.36** | -1.82** | -1.87** | -2.36** | -1.82** | -1.86** | -2.34** | -1.81** | -1.84** | -2.29** | -1.81** | -1.85** |

| (0.81) | (0.29) | (0.56) | (0.81) | (0.29) | (0.56) | (0.81) | (0.29) | (0.56) | (0.81) | (0.29) | (0.57) | |

| JVM12 | -0.05 | -0.42 | 1.07** | -0.06 | -0.43 | 1.06** | -0.10 | -0.45 | 1.05** | -0.04 | -0.44 | 1.05** |

| (0.53) | (0.28) | (0.34) | (0.53) | (0.28) | (0.34) | (0.54) | (0.28) | (0.34) | (0.53) | (0.28) | (0.34) | |

| EPN12 | 0.65* | -1.07** | -0.44 | 0.65* | -1.07** | -0.43 | 0.67* | -1.09** | -0.47 | 0.71** | -1.09** | -0.42 |

| (0.35) | (0.25) | (0.RAC37) | (0.35) | (0.25) | (0.37) | (0.36) | (0.25) | (0.37) | (0.36) | (0.25) | (0.37) | |

| Married | -0.49 | -0.37** | -0.28 | -0.49 | -0.37** | -0.29 | -0.53* | -0.38** | -0.30 | -0.51* | -0.36* | -0.31 |

| (0.30) | (0.19) | (0.28) | (0.30) | (0.19) | (0.28) | (0.30) | (0.19) | (0.28) | (0.31) | (0.19) | (0.28) | |

| Pid PID | 3.07** | 0.76* | 0.48 | 3.07** | 0.77* | 0.48 | 3.14** | 0.76* | 0.51 | 3.06** | 0.76* | 0.45 |

| (0.41) | (0.40) | (0.54) | (0.41) | (0.40) | (0.54) | (0.42) | (0.41) | (0.54) | (0.42) | (0.40) | (0.54) | |

| Pid PAN | 0.76 | 1.37** | 3.67** | 0.77 | 1.37** | 3.68** | 0.85 | 1.33** | 3.67** | 0.77 | 1.30* | 3.70** |

| (1.18) | (0.66) | (0.60) | (1.18) | (0.66) | (0.60) | (1.18) | (0.66) | (0.60) | (1.18) | (0.67) | (0.61) | |

| Pid Morena | -1.70** | -1.26** | -2.75** | -1.70** | -1.26** | -2.77** | -1.73** | -1.28** | -2.82** | -1.69** | -1.28** | -2.71** |

| (0.62) | (0.24) | (0.74) | (0.62) | (0.24) | (0.74) | (0.63) | (0.24) | (0.74) | (0.62) | (0.24) | (0.74) | |

| Ideology | 0.15** | 0.06 | 0.15** | 0.15** | 0.06 | 0.15** | 0.14** | 0.05 | 0.16** | 0.14** | 0.05 | 0.15** |

| (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Education | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.01 | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.01 | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.02 | -0.05 | -0.08 | -0.01 |

| (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Income | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.10 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.10 | -0.00 | -0.01 | -0.09 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.09 |

| (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.08) | |

| Urban | -0.04 | -0.04 | -0.12 | -0.04 | -0.04 | -0.13 | -0.04 | -0.04 | -0.13 | -0.05 | -0.04 | -0.13 |

| (0.21) | (0.12) | (0.17) | (0.21) | (0.12) | (0.17) | (0.21) | (0.12) | (0.18) | (0.21) | (0.12) | (0.17) | |

| Age | -0.03 | -0.05 | -0.09 | -0.03 | -0.05 | -0.09 | -0.06 | -0.05 | -0.10 | -0.04 | -0.05 | -0.10 |

| (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.10) | |

| North | -0.39 | 0.20 | 0.26 | -0.39 | 0.19 | 0.26 | -0.39 | 0.18 | 0.26 | -0.37 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| (0.39) | (0.24) | (0.34) | (0.39) | (0.24) | (0.34) | (0.39) | (0.24) | (0.34) | (0.39) | (0.24) | (0.34) | |

| South | -1.08** | -0.57** | -0.76* | -1.09** | -0.58** | -0.78* | -1.15** | -0.58** | -0.77* | -1.11** | -0.58** | -0.75* |

| (0.45) | (0.26) | (0.42) | (0.45) | (0.26) | (0.42) | (0.46) | (0.26) | (0.42) | (0.45) | (0.26) | (0.42) | |

| West | -0.15 | 0.33 | 0.36 | -0.15 | 0.33 | 0.36 | -0.14 | 0.38 | 0.37 | -0.12 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| (0.43) | (0.25) | (0.36) | (0.43) | (0.25) | (0.36) | (0.43) | (0.26) | (0.36) | (0.43) | (0.26) | (0.36) | |

| TV News | 0.11 | -0.06 | -0.11 | 0.11 | -0.06 | -0.12 | 0.09 | -0.06 | -0.11 | 0.11 | -0.06 | -0.11 |

| (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Interest pol. | -0.38 ** | -0.30 ** | -0.33 ** | -0.38 ** | -0.31** | -0.34** | -0.39** | -0.30** | -0.32** | -0.38** | -0.29** | -0.35** |

| (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.10) | (0.15) | |

| Catholic | 0.11 | 0.35 | -0.11 | 0.47 | -0.66** | -0.82* | 4.64** | 1.88** | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.46 | -0.05 |

| (0.57) | (0.35) | (0.55) | (0.71) | (0.32) | (0.46) | (2.03) | (0.96) | (1.47) | (0.58) | (0.35) | (0.55) | |

| Prot.-Ev. | -0.38 | 1.02** | 0.56 | -2.15 | -0.41 | -0.82 | -8.50 | -1.28 | -3.66 | |||

| (0.91) | (0.46) | (0.72) | (1.76) | (0.84) | (1.33) | (5.51) | (1.69) | (2.82) | ||||

| Attendance | -0.24** | -0.13* | 0.02 | -0.24** | -0.14* | -0.01 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.52 | -0.25** | -0.18** | 0.01 |

| (0.12) | (0.07) | (0.11) | (0.12) | (0.07) | (0.11) | (0.53) | (0.24) | (0.36) | (0.12) | (0.07) | (0.11) | |

| Relig. leader | -0.06 | -0.14* | -0.21* | -0.06 | -0.14* | -0.22* | 0.05 | 0.11 | -0.34 | -0.09 | -0.16** | -0.24** |

| (0.13) | (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.13) | (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.36) | (0.19) | (0.32) | (0.13) | (0.08) | (0.12) | |

| Moral values | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.25* | 0.03 | 0.06 | -0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.15) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | |

| None | 0.32 | -1.04** | -0.97 | |||||||||

| (0.91) | (0.47) | (0.73) | ||||||||||

| Cath:Att | -0.39 | -0.48* | -0.55 | |||||||||

| (0.55) | (0.25) | (0.38) | ||||||||||

| Cath:Rel L | -0.14 | -0.31 | 0.14 | |||||||||

| (0.38) | (0.20) | (0.34) | ||||||||||

| Cath:Moral | -0.34** | -0.03 | -0.01 | |||||||||

| (0.15) | (0.07) | (0.11) | ||||||||||

| Prot-Ev:Att | 0.20 | 0.48* | 0.15 | |||||||||

| (0.61) | (0.27) | (0.40) | ||||||||||

| Prot-Ev:Rel L | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.27 | |||||||||

| (0.53) | (0.27) | (0.41) | ||||||||||

| Prot-Ev:Moral | 0.48 | -0.01 | 0.24 | |||||||||

| (0.40) | (0.11) | (0.17) | ||||||||||

| Constant | -0.21 | 2.08** | -0.09 | -0.53 | 3.11** | 0.82 | -3.96* | 0.91 | -0.42 | 0.14 | 2.11** | 0.21 |

| (1.42) | (0.83) | (1.20) | (1.65) | (0.93) | (1.36) | (2.21) | (1.08) | (1.63) | (1.44) | (0.84) | (1.21) | |

| log Lik | -822.7 | -822.3 | -815.5 | -817.3 | ||||||||

| McFadden R2 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 | ||||||||

| Observations | 994 | 994 | 994 | 994 | ||||||||

Source: Multinomial logistic models, reference category vote for AMLO. 2018 CNEP Mexico’ sample. **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Multinomial regressions compare the effect of explanatory variables on each category of the dependent variable, taking one category as reference. In Tables 2 and 3, the reference category of the dependent variable is vote for AMLO. In both tables, statistically significant variables are marked, and positive signs indicate support for JAM (PRI), others, or RAC (PAN-PRD), whereas negative signs indicate support for AMLO (Morena).

Models from Table 2 suggest that the higher levels of Church attendance increase support for AMLO, when compared to the PRI and other political options, whereas the stronger preferences for political leaders with religious principles increase support for AMLO, when compared to the PAN’s candidate. Interestingly, model 2 shows that Protestants/Evangelicals are more likely to prefer other political options when compared to AMLO. Additionally, moral values do not play any role, as seen in model 3.

Regarding control variables, previous vote for AMLO and EPN, being married, living in the South, holding a leftist ideology, and keeping interest in politics increased support for AMLO. In contrast, women, previous vote for JVM, and party identification with the PAN and the PRI decreased support for Morena’s candidate.

In order to fully test whether religious factors are associated to vote choice, Table 3 shows two models, labelled as 5, and 6. These two models show interaction terms between religious affiliations and religious factors. One model shows interaction terms for Catholics, whereas the other one shows interaction terms for Protestants/Evangelicals.

Across Catholics, Church attendance and moral values increase the likelihood to vote for AMLO, whereas political leadership with religious principles did not show any statistical significance. Across Protestants/Evangelicals, Church attendance decreases support for AMLO, whereas moral values and political leadership with religious principles did not play any role.

Overall, Catholics who frequently attend Church and hold traditional moral values were more likely to vote for AMLO, whereas Protestants/Evangelicals who frequently attend Church are less likely to support him. Thus, available evidence suggests that arguably, religious appeals made by Morena’s candidate have a positive impact on Catholic voters, whereas the same appeals did not work so well among Protestants and Evangelicals.

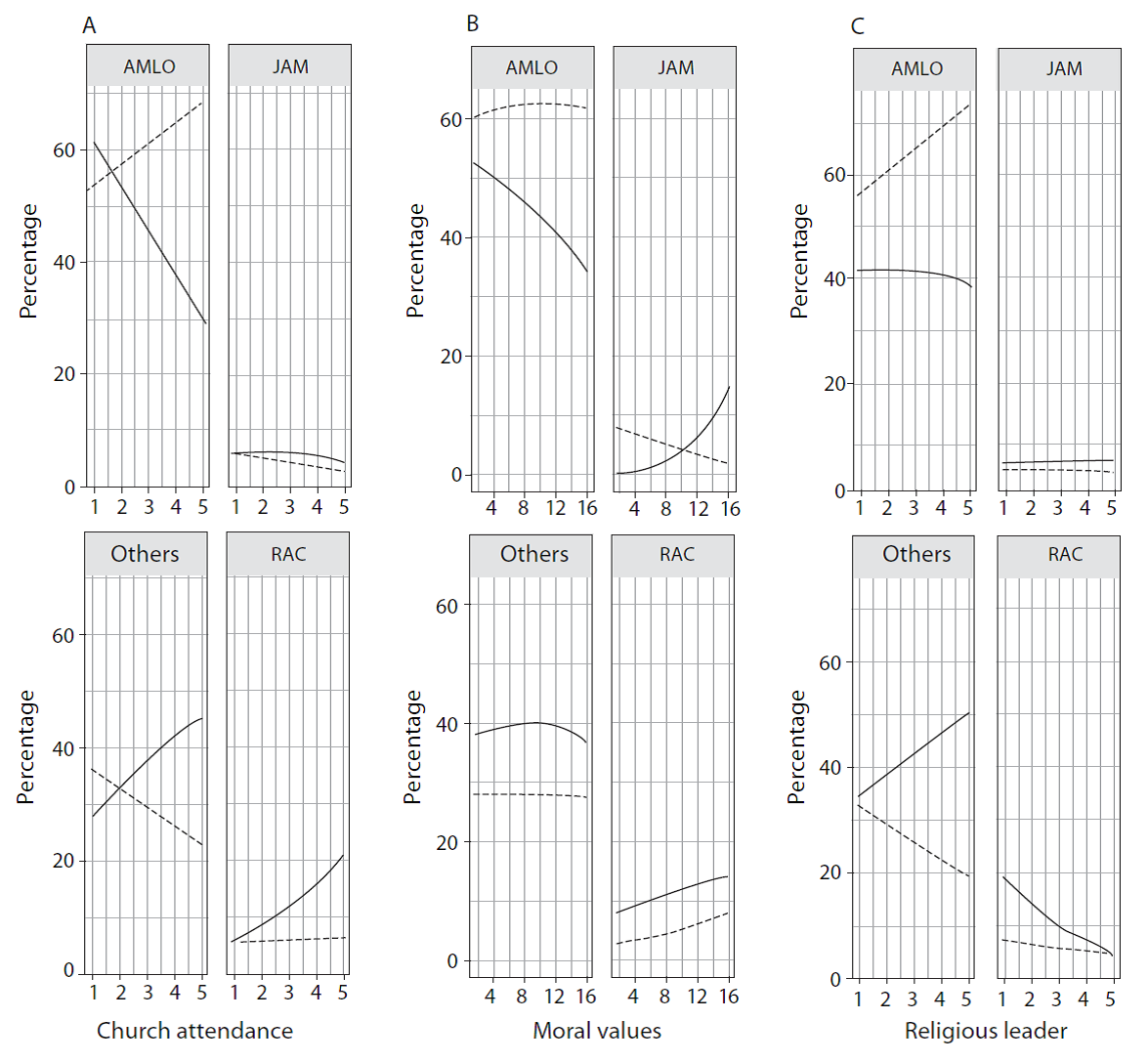

In order to enhance our understanding of multinomial logistic models, estimations of predicted probabilities of main variables of interest are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The first figure shows three panels among Catholics: A) Church attendance, B) moral values, and C) preferences for a leader with religious principles.

Source: Model 5 from Table 3. Author’s estimations using R, library sjPlot (Lüdecke, 2019). Catholics are dashed lines, non-Catholics and secularists are solid lines.

FIGURE 1 Predicted probabilities of vote choice among Catholics, Mexico 2018

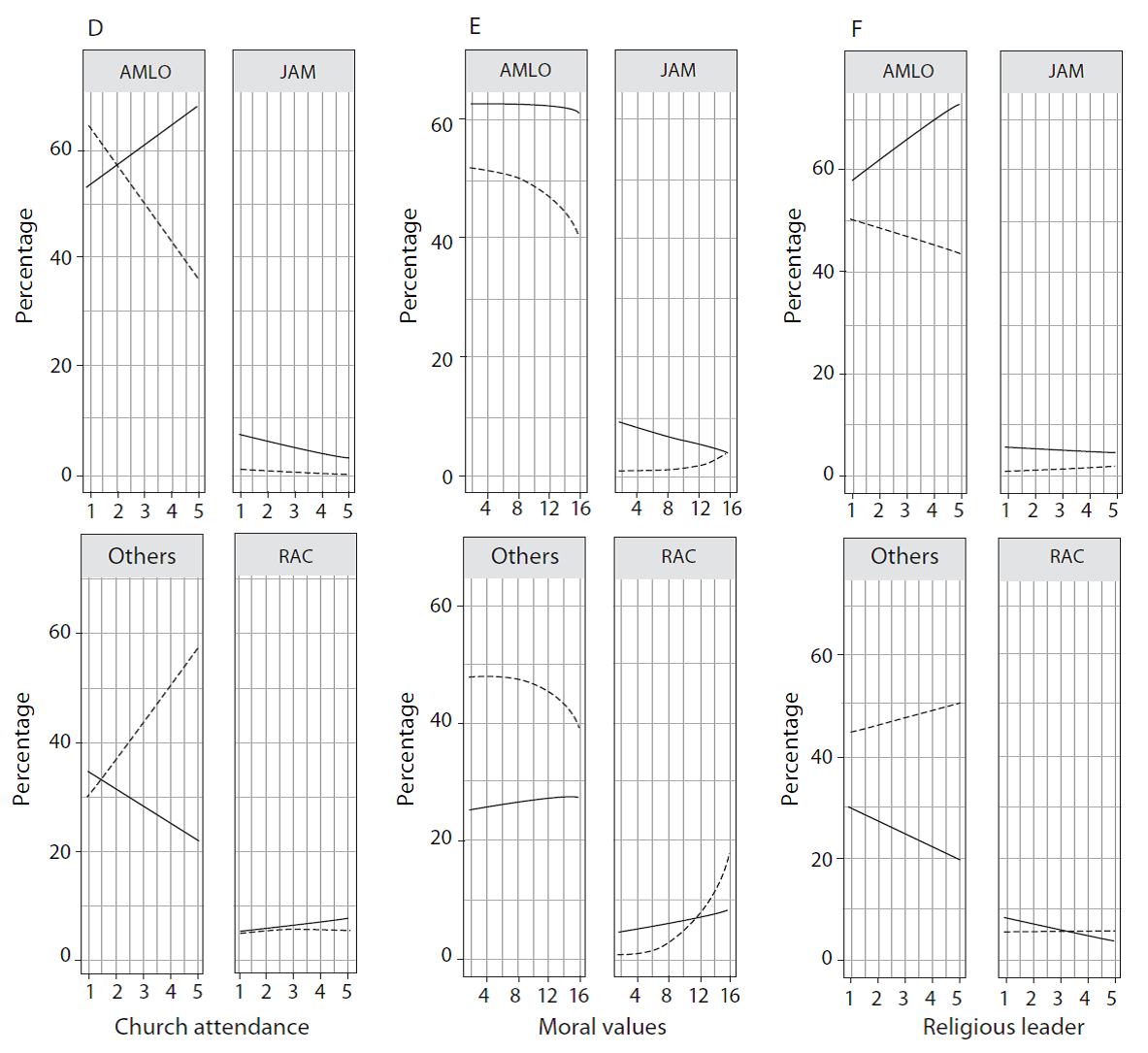

Source: Model 6 from Table 3. Author’s estimations using R, library sjPlot (Lüdecke, 2019). Protestants/Evangelicals are dashed lines, Catholics and secularists are solid lines.

FIGURE 2 Predicted probabilities of vote choice among Protestants/Evangelicals, Mexico 2018

Catholics who frequently attend Church increase support for AMLO in 16 points, from 52 among those who practically never attend to 68 among those who attend on weekly basis. In contrast, other options lose support. Regarding moral values, although AMLO gains some points among Catholics, the main effect works when compared to non-Catholics. In addition, the PAN’s candidate also wins support within Catholics with highly religious moral values, whereas the PRI’s candidate losses it. Finally, regarding preferences for leaders with religious principles among Catholics, AMLO increases support, whereas all other candidates lose points.

The second graph also shows the same three panels but among Protestants and Evangelicals. AMLO losses support in all tree panels, whereas other options increase it among Protestant and Evangelical church goers (panel D), and those who strongly prefer a leader with religious principles (panel F). Regarding moral values, AMLO and other options lose support, whereas the PAN’s candidate increases 16 points (panel E).5

Conclusions

Although more theoretical and empirical work is required, there is preliminary evidence that suggests that religious variables are related to preferences for the left wing in Mexico. This finding derives from statistical analyses from the 2018 CNEP surveys. Overall, Catholic church attendance and preferences for leaders with religious principles seemed to slightly increase the likelihood to vote for López Obrador. Among other factors that explain this noticeable change, it is important to consider AMLO’ discourse, in which he emphasized values in a generic sense, continuously making religious appeals, and avoiding specifics on controversial issues, such as debates over moral values.

In this way, Morena not only became an attractive party for its traditional leftwing constituency, but also for observant Catholics, allowing AMLO to win the election by means of building a broader coalition among secular and religious Catholic voters.

Therefore, it is plausible to guess that López Obrador will continue to make religious appeals, avoiding controversies over moral values to retain religious voters. In addition, AMLO will need to offer specific policies that favor Protestants and Evangelicals, such as access to mass media and increasing public appearances, in order to gain, as much as possible, Evangelical clergy and parishioners’ support.

Taking all these pieces of evidence together, these insightful findings could entail an important shift in Mexico’s religious division, in which the socially conservative left would receive support from observant Catholics. This distinction seems to depend on whether controversies over moral values are not specifically discussed in campaigns. This could imply that moral values are more relevant to Protestants and Evangelicals, and for these voters AMLO’s vague message on this front did not play well.

Finally, these potential mechanisms require further theoretical and empirical elaboration to disentangle how and why religious voters are to some extent, taking sides with Mexico’s new leftist political party. It also opens doors for future research in Mexican politics, in which a relevant test would be whether candidates who are making religious appeals or talking about values in a generic sense, they could attract or get away religious voters across religious affiliations.

REFERENCES

Agreen, David (2018), “Mexico Election: Why is the Leftwing Frontrunner so Quiet on Social Issues?”, The Guardian, 27 de junio, disponible en: Agreen, David (2018), “Mexico Election: Why is the Leftwing Frontrunner so Quiet on Social Issues?”, The Guardian, 27 de junio, disponible en: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/27/mexico-election-candidates-avoid-stances-on-same-sex-marriage-and-abortion [fecha de consulta: 27 de septiembre de 2019]. [ Links ]

Althoff, Andrea (2019), “Right-Wing Populism and Evangelicalism in Guatemala: The Presidency of Jimmy Morales”, International Journal of Latin American Religions, 3(1), pp. 294-324, disponible en: 294-324, disponible en: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41603-019-00090-2 [fecha de consulta: 1 de julio de 2020]. [ Links ]

Barracca, Steve y Matthew L. Howell (2014), “The Persistence of the Church-State Conflict in Mexico’s Evangelical Vote: The Story of an Outlier”, The Latin Americanist, 58(2), pp. 23-47, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/tla.12025. [ Links ]

Barranco, Bernardo (2018), “López Obrador, el candidato de Dios”, La Jornada, 30 de mayo, disponible en: Barranco, Bernardo (2018), “López Obrador, el candidato de Dios”, La Jornada, 30 de mayo, disponible en: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2018/05/30/opinion/019a2pol [fecha de consulta: 27 de diciembre de 2019]. [ Links ]

Beer, Caroline y Victor D. Cruz-Aceves (2018), “Extending Rights to Marginalized Minorities: Same-Sex Relationship Recognition in Mexico and the United States”, State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 18(1), pp. 3-26, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440017751421. [ Links ]

Boas, Taylor y Amy Erica Smith (2015), “Religion and the Latin American Voter”, en Ryan Carlin, Matt Singer y Elizabeth Zechmeister (eds.), The Latin American Voter, Ann Arbor:University of Michigan Press, pp. 99-121, doi: 10.3998/mpub.8402589. [ Links ]

Buckley, David (2016), “Demanding the Divine? Explaining Cross National Support for Clerical Control of Politics”, Comparative Political Studies, 49(3), pp. 357-390, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617964 [ Links ]

Camp, Roderic Ai (1997), Crossing Swords: Politics and Religion in Mexico, Nueva York: Oxford University Press, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617964. [ Links ]

Camp. Roderic Ai (2008), “Exercising Political Influence, Religion, Democracy, and the Mexican 2006 Presidential Race”, Journal of Church and State, 50(1), pp. 49-72, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jcs/50.1.49. [ Links ]

Campbell, David E., Geoffrey C. Layman y John C. Green (2016), “A Jump to the Right, A Step to the Left: Religion and Public Opinion”, en Adam J. Berinsky, New Directions in Public Opinion, Nueva York: Routledge, pp. 232-258. [ Links ]

Chand, Vikram K. (2001), Mexico’s Political Awakening, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [ Links ]

Charles-Leija, Humberto, Aldo Josafat Torres y Laura Maribel Colima (2018), “Características sociodemográficas del voto para diputados, 2015”, Revista de El Colegio de San Luis, 8(17), pp. 107-135, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.21696/rcsl8172018809. [ Links ]

Chaves, João (2015), “Latin American Liberation Theology: The Creation, Development, Contemporary Situation of an On-Going Movement”, en Stephen Hunt, Handbook of Global Contemporary Christianity: Themes and Developments in Culture, Politics, and Society, Boston: Brill, pp. 113-128. [ Links ]

CNEP (Comparative National Elections Project) (2018), The 2018 Mexico’s Postelectoral Survey, disponible en: CNEP (Comparative National Elections Project) (2018), The 2018 Mexico’s Postelectoral Survey, disponible en: https://u.osu.edu/cnep/surveys/surveys-through-2012/ [fecha de consulta: 20 de septiembre de 2018]. [ Links ]

De la Torre, Renée (1996), “Pinceladas de una ilustración etnográfica: La Luz del Mundo en Guadalajara”, en Gilberto Giménez (ed.), Identidades religiosas y sociales en México, Ciudad de México: UNAM, pp. 145-174. [ Links ]

Díaz Domínguez, Alejandro (2006), “¿Influyen los ministros de culto sobre la intención de voto?” Perfiles Latinoamericanos, 28(2), pp. 33-57, disponible en: 33-57, disponible en: https://perfilesla.flacso. edu.mx/index.php/perfilesla/article/view/214 [fecha de consulta: fecha de consulta: 8 de febrero de 2020]. [ Links ]

Díaz Domínguez, Alejandro (2013), “Iglesia, evasión e involucramiento político en América Latina”, Política y Gobierno, XX(1), pp. 3-38, disponible en: 3-38, disponible en: http://www.politicaygobierno.cide.edu/index.php/pyg/article/view/129/46 [fecha de consulta: 1 de julio de 2020]. [ Links ]

Díaz Domínguez, Alejandro (2014), “Bases sociales del voto”, en Alejandro Moreno y Gustavo Meixueiro (coords.), El comportamiento electoral mexicano en las elecciones de 2012, Ciudad de México: CESOP, pp. 41-62. [ Links ]

Díaz Domínguez, Alejandro (2019), “El voto religioso: ¿Un ‘mandato moral’?”, en Alejandro Moreno, Alexandra Uribe Coughlan, y Sergio C. Wals (coords.), El viraje electoral: Opinión pública y voto en las elecciones de 2018, Ciudad de México: CESOP, pp. 75-101. [ Links ]

Domínguez, Jorge y James McCann (1996), Democratizing Mexico: Public Opinion and Electoral Choices, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Fortuny, Patricia (1996), “Mormones y Testigos de Jehová: La versión mexicana”, en Gilberto Giménez (ed.), Identidades religiosas y sociales en México, Ciudad de México: UNAM-IFAL, pp. 175-215. [ Links ]

Freston, Paul (2009), “Christianity: Protestantism”, en Jeff Haynes (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Religion and Politics, Nueva York: Routledge, pp. 26-47. [ Links ]

García, Eduardo (1999), “Religiosidad y prensa escrita en Oaxaca: Apuntes para iniciar un estudio detallado”, en Sergio Inestrosa (ed.), Las Iglesias y la agenda de la prensa escrita en México, Ciudad de México: Universidad Iberoamericana, pp. 29-50. [ Links ]

Garma, Carlos (2019), “Religión y política en las elecciones del 2018: Evangélicos mexicanos y el Partido Encuentro Social”, Alteridades, 29(57), pp. 35-46, doi: http://www.doi. org/10.24275/uam/izt/dcsh/alteridades/2019v29n57/Garma. [ Links ]

Gill, Anthony (1999), “The Politics of Regulating Religion in Mexico: The 1992 Constitutional Reforms in Historical Context”, Journal of Church and State, 41(4), pp. 761-794, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jcs/41.4.761. [ Links ]

Hagopian, Frances (2009), “Social Justice, Moral Values or Institutional Interests? Church Responses to the Democratic Challenge in Latin America”, en Frances Hagopian (ed.), Religious Pluralism, Democracy, and the Catholic Church in Latin America, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 257-331. [ Links ]

Hale, Christopher (2015), “Religious Institutions and Civic Engagement: A Test of Religion’s Impact on Political Activism in Mexico”, Comparative Politics, 47(2), pp. 211- 230, doi: https://doi.org/10.5129/001041515814224435. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) (2010), Censo general de población y vivienda 2010: Resultados Preliminares, Ciudad de México: INEGI. [ Links ]

Imai, Kosuke y David A. van Dyk (2005), “MNP: R Package for Fitting the Multinomial Probit Model”, Journal of Statistical Software, 14(3), pp. 1-32, disponible en: 1-32, disponible en: https://imai. fas.harvard.edu/research/files/MNPjss.pdf [fecha de consulta: 1 de julio de 2020]. [ Links ]

Klesner, Joseph (1987), “Changing Patterns of Electoral Participation and Official Party Support in Mexico”, en Judith Gentleman (ed.), Mexican Politics in Transition, Boulder: Westview, pp. 95-152. [ Links ]

Lacerda, Fábio (2018), “Assessing the Strength of Pentecostal Churches’ Electoral Sup- port: Evidence from Brazil”, Journal of Politics in Latin America, 10(2), pp. 3-40, disponible en: 3-40, disponible en: https://journals.sub.uni-hamburg.de/giga/jpla/article/view/1120/ [fecha de consulta: 1 de julio de 2020]. [ Links ]

Lamadrid, José Luis (1994), La larga marcha a la modernidad en materia religiosa, Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Lee Anderson, Jon (2018), “A New Revolution in Mexico”, The New Yorker, 25 de junio, disponible en: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/06/25/a-new-revolution-in-mexico [fecha de consulta: septiembre de 2019]. [ Links ]

Lies, William y Mary F.T. Malone (2006), “The Chilean Church: Declining Hegemony?” en Paul Christopher Manuel, Lawrence C. Reardon y Clyde Wilcox (eds.), The Catholic Church and the Nation State. Comparative Perspectives, Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, pp. 89-100. [ Links ]

Lindhardt, Martin y Jakob Egeris Thorsen (2015), “Christianity in Latin America. Struggle and Accommodation”, en Stephen Hunt (ed.), Handbook of Global Contemporary Christianity: Themes and Developments in Culture, Politics, and Society, Boston: Brill, pp. 167-187. [ Links ]

Lipset, Seymour Martin y Stein Rokkan (1967[1990]), “Cleavage Structures, Party Sys- tems, and Voter Alignments”, en Peter Mair (ed.), The West European Party System, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 91-138. [ Links ]

Lodola, Germán y Margarita Corral (2013) “Support for Same-Sex Marriage in Latin America”, en Jason Pierceson, Adriana Piatti-Crocker y Shawn Schulenberg (ed.), SameSex Marriage in Latin America: Promise and Resistance, Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 41-52. [ Links ]

Lüdecke, Daniel (2019), sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Sciences, disponible en: Lüdecke, Daniel (2019), sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Sciences, disponible en: https://strengejacke.github.io/sjPlot/ [fecha de consulta: 1 de julio de 2020]. [ Links ]

Luengo, Enrique (1992), “La percepción política de los párrocos en México”, en Carlos Martínez Assad (ed.), Religiosidad y política en México, Ciudad de México: Universidad Iberoamericana, pp. 199-239. [ Links ]

Mabry, Donald (1973), Mexico’s Acción Nacional: A Catholic Alternative to Revolution, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [ Links ]

Magaloni, Beatriz y Alejandro Moreno (2003), “Catching All Souls: the pan and the Politics of Religion in Mexico”, en Scott Mainwaring y Timothy R. Scully (ed.), Christian Democracy in Latin America: Electoral Competition and Regime Conflicts, Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 247-274. [ Links ]

Mattiace, Shannan (2019), “Mexico 2018: AMLO’s Hour”, Revista de Ciencia Política 39(2), pp. 285-311, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-090X2019000200285. [ Links ]

Meyer, Jean (1973), La Cristiada, Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Monsiváis, Carlos (1992), “Tolerancia religiosa, derechos humanos y democracia”, en VV.AA. (eds.), Las iglesias evangélicas y el Estado mexicano, Ciudad de México: CUPSA, pp. 165-176. [ Links ]

Morales, Gilberto y Esperanza Palma (2019), “Agendas de género en las campañas presidenciales de 2018 en México”, Alteridades, 29(57), pp. 47-58, doi: https://dx.doi. org/10.24275/uam/izt/dcsh/alteridades/2019v29n57/morales. [ Links ]

Morales, Mauricio (2016), “Tipos de identificación partidaria: América Latina en perspec- tiva comparada, 2004-2012”, Revista de Estudios Sociales, 57(3), pp. 25-42, doi: http:// dx.doi.org/10.7440/res57.2016.02. [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro (1999), “Campaign Awareness and Voting in the 1997 Mexican Congressional Elections”, en Jorge Domínguez y Alejandro Poiré (eds.), Toward Mexico’s Democratization: Parties, Campaigns, Elections, and Public Opinion, Nueva York: Routledge, pp. 114-146. [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro (2003), El votante mexicano: Democracia, actitudes políticas y conducta electoral, Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro (2009), “The Activation of the Economic Voting in the 2006 Campaign”, en Jorge Domínguez, Chappell Lawson y Alejandro Moreno (eds.), Consolidating Mexico’s Democracy: The 2006 Presidential Campaign in Comparative Perspective, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 209-228. [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro (2018a), “¿Anaya lavó dinero? ¿Vargas Llosa tiene razón? Esto piensan los mexicanos”, El Financiero, 7 de marzo. [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro (2018b), El cambio electoral: Votantes, encuestas y democracia en México, Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro y Yuritzi Mendizábal (2015), “El uso de las redes sociales y el comportamiento político en México”, en Helcimara Telles y Alejandro Moreno (coords.), El votante latinoamericano: Comportamiento electoral y comunicación política, Ciudad de México: CESOP, pp. 293-320. [ Links ]

Muro González, Víctor (1994), Iglesia y movimientos sociales en México: Los casos de Ciudad Juárez y el Istmo de Tehuantepec, Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Norris, Pippa y Ronald Inglehart (2004), Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Parker, Cristián (2016), “Religious Pluralism and New Political Identities in Latin America”, Latin American Perspectives, 43(3), pp. 15-30, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X15623771. [ Links ]

Rosseel, Yves (2012), “lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling”, Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), pp. 1-36, disponible en: 1-36, disponible en: https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v048i02 [fecha de consulta: 1 de julio de 2020]. [ Links ]

Ruiz, Leticia (2015), “Oferta partidista y comportamiento electoral en América Latina”, en Helcimara Telles y Alejandro Moreno (coords.), El votante latinoamericano: Comportamiento electoral y comunicación política, Ciudad de México: CESOP, pp. 19-38. [ Links ]

Sarmet, Carlos Gustavo y Wania Amelia Belchior Mesquita (2016), “Political Conflict and Spiritual Battle: Intersections between Religion and Politics among Brazilian Pentecostals”, Latin American Perspectives, 208(43), pp. 85-103, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X 16640267. [ Links ]

Smith, Amy Erica (2019), Religion and Brazilian Democracy: Mobilizing the People of God, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108699655. [ Links ]

Soriano, Rodolfo (1999), En el nombre de Dios: Religión y democracia en México, Ciudad de México: Instituto Mora-IMDOSOC. [ Links ]

Telles, Helcimara, Pedro Santos Mundim y Nayla Lopes (2014), “Internautas, verdes y pentecostales: ¿Nuevos patrones de comportamiento político en Brasil?”, en Helcimara Telles y Alejandro Moreno (coords.), El votante latinoamericano: Comportamiento electoral y comunicación política, Ciudad de México: cesop, pp. 113-158. [ Links ]

Thiessen, Joel y Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme (2017), “Becoming a Religious None: Irreligious Socialization and Disaffiliation”, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 56(1), pp. 64- 82, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12319. [ Links ]

Torcal, Mariano (2014), “Bases ideológicas y valorativas del votante mexicano y su efecto en el voto: Síntomas de una creciente institucionalización”, en Alejandro Moreno y Gustavo Meixueiro (coords.), El comportamiento electoral mexicano en las elecciones de 2012, Ciudad de México: CESOP, pp. 91-116. [ Links ]

Trejo, Guillermo (2009), “Religious Competition and Ethnic Mobilization in Latin America: Why the Catholic Church Promotes Indigenous Movements in Mexico”, American Political Science Review, 103(3), pp. 323-342, doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990025. [ Links ]

Tusalem, Rollin (2009), “The Role of Protestantism in Democratic Consolidation among Transitional States”, Comparative Political Studies, 42(7), pp. 882-915, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414008330596. [ Links ]

Woodberry, Robert D. (2012), “The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy”, American Political Science Review, 106(7), pp. 244-274, doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000093. [ Links ]

1The 1992 constitutional reform adopted during Salinas administration (1988-1994) on Church-State relations undoubtedly changed the mechanics of the interrelationship between religion and politics. The only restriction which remains is the prohibition for churches and clergy to induce parishioners voting decisions (Lamadrid, 1994; Gill, 1999; Díaz Domínguez, 2006; Camp, 2008). Interestingly, at the time, 53 per cent of Catholic clergy believed that bishops should make greater efforts to promote Church’s values against government’s policies (Luengo, 1992: 227).

2 In addition to international press stories which profusely documented AMLO’s religious appeals, such as stories published by The Guardian and The New Yorker, Mexico’ national press also covered similar stories: during an interview aired in Milenio TV on March 22, 2018, Morena’s candidate, in relation to abortion and same sex marriage stated: “my position is that these cases could be consulted, because I cannot offend those who. I am the leader of a broad, plural, inclusive movement, where there are Catholics, there are Evangelicals, there are non-believers, I have to consult the opinion of all”, suggesting a strategy to avoid being specific on controversial issues.

3There are additional examples of religious appeals, such as the implicit association between Morena and the light brown skin color of Our Lady of Guadalupe, o the specific day in which López Obrador received the official registry as presidential candidate at the Electoral Management Body (INE), December 12, same day in which is the festivity of the Virgin of Guadalupe (Barranco, 2018).

4Additional regressions included structural equation models (see online appendix), in which vote for Morena was the dependent variable, and explanatory variables were demographics, party identification, vote choice in 2012, religious variables, feeling thermometers, and evaluations on issues. The last three groups were previously estimated considering their respective latent variables. Other two models (see online appendix) were binary logistic regressions, in which vote for Morena was the dependent variable, and a multinomial probit model in a Bayesian framework. Results were essentially consistent with the reported multinomial logistic regressions here (these additional models are available from the author).

5Interactive models among secularists and religious dimensions (not shown) revealed statistically insignificant coefficients for interaction terms. In addition, Church attendance was dropped from the interactive model across secularists, due to the lack of variation, because all secularists cases were placed in the “I practically never attend Church” cell.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1 Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Mean | Std.Dev. | Min. | Max. | Pct. Valid. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abortion | 2.91 | 0.97 | 1 | 4 | 96.64 |

| AMLO12 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| AMLO18 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Church attendance | 3.34 | 1.50 | 1 | 5 | 99.37 |

| Catholic | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Central | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Corruption perception | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Voices Critics (demo) | 1.74 | 0.90 | 1 | 4 | 98.11 |

| Elections (demo) | 1.47 | 0.72 | 1 | 4 | 98.39 |

| Employment (demo) | 1.33 | 0.63 | 1 | 4 | 98.53 |

| Income gap (demo) | 1.59 | 0.81 | 1 | 4 | 97.41 |

| Minorities (demo) | 1.53 | 0.78 | 1 | 4 | 96.01 |

| Free pres (demo) | 1.61 | 0.84 | 1 | 4 | 96.64 |

| Eco growth (econ) | 4.03 | 3.12 | 1 | 10 | 99.37 |

| Age | 3.60 | 1.67 | 1 | 6 | 100.00 |

| EPN12 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Equality (econ) | 5.9 | 3.25 | 1 | 10 | 98.67 |

| Education | 4.84 | 1.95 | 1 | 9 | 99.86 |

| Corruption (ev natl gov) | 4.3 | 0.78 | 1 | 5 | 99.02 |

| Crime (ev natl gov) | 4.06 | 0.85 | 1 | 5 | 99.02 |

| Employment (ev natl gov) | 4.00 | 0.85 | 1 | 5 | 98.88 |

| Nat eco (ev natl gov) | 3.86 | 0.83 | 1 | 5 | 99.51 |

| Poverty (ev natl gov) | 4.12 | 0.83 | 1 | 5 | 99.16 |

| Feelings AMLO | 7.34 | 3.02 | 0 | 10 | 97.48 |

| Gay adoption | 2.97 | 1.01 | 1 | 4 | 96.85 |

| Gay marriage | 2.61 | 1.05 | 1 | 4 | 96.15 |

| Gender | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| PID Morena | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| PID PAN | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| PID PRI | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Income | 2.88 | 1.92 | 1 | 9 | 90.20 |

| Interest in Politics | 2.28 | 0.95 | 1 | 4 | 99.86 |

| Left Right | 5.22 | 2.82 | 1 | 10 | 78.36 |

| JAM18 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| JVM12 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Relig law | 4.39 | 3.14 | 1 | 10 | 98.53 |

| Urban | 2.52 | 0.76 | 1 | 3 | 100.00 |

| Marijuana | 3.01 | 0.97 | 1 | 4 | 98.11 |

| North | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Death penalty | 2.56 | 1.09 | 1 | 4 | 97.27 |

| Priv/Pub (econ) | 7.49 | 2.89 | 1 | 10 | 98.95 |

| Prot/Evang | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| RAC18 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Rel Princ/Leader | 2.21 | 1.21 | 1 | 5 | 98.04 |

| Religious groups | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Resp gov (econ) | 6.20 | 3.18 | 1 | 10 | 99.09 |

| Security perception | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Services taxes (econ) | 6.15 | 3.11 | 1 | 10 | 98.18 |

| Women role (econ) | 7.54 | 2.96 | 1 | 10 | 99.65 |

| South | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 100.00 |

| TV News | 3.82 | 1.48 | 1 | 5 | 100.00 |

Source: Mexican Sample of the 2018 CNEP post electoral surveys, 1 428 respondents in total.

TABLE A2 Vote Choice for Morena, Structural Equation Models

| Model I | Model II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent variables | Estimate | Std.Err. | Beta | Estimate | Std.Err. | Beta |

| Religiosity | ||||||

| Church attendance | 1.000 | 0.730 | ||||

| Religious groups | 0.029 | 0.015 | 0.185+ | |||

| Religion on politics | ||||||

| Religious principles/Leader | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.292 | |||

| Religious law | 3.788 | 0.598 | 0.482* | 4.350 | 1.024 | 0.494* |

| Moral values | ||||||

| Abortion | 1.000 | 0.664 | 1.000 | 0.621 | 0.645 | |

| Gay marriage | 1.227 | 0.061 | 0.753* | 1.301 | 0.076 | 0.777* |

| Gay adoption | 1.197 | 0.059 | 0.763* | 1.278 | 0.074 | 0.779* |

| Death penalty | -0.556 | 0.056 | -0.331* | -0.575 | 0.068 | -0.332* |

| Marijuana | 1.035 | 0.055 | 0.682* | 1.022 | 0.067 | 0.646* |

| Economics | ||||||

| Equality | 1.000 | 0.075 | 1.000 | 0.089 | ||

| Services taxes | 2.032 | 1.227 | 0.159+ | 1.693 | 1.031 | 0.157+ |

| Economic growth | -1.880 | 1.149 | -0.148+ | -1.359 | 0.929 | -0.131 |

| Private/Public enterprises | 3.397 | 1.918 | 0.284+ | 2.967 | 1.750 | 0.301+ |

| Responsive government | 1.650 | 1.048 | 0.126 | 2.245 | 1.371 | 0.204+ |

| Women role | 7.945 | 4.489 | 0.652+ | 5.652 | 3.299 | 0.562+ |

| Democracy | ||||||

| Voice of critics | 1.000 | 0.499 | 1.000 | 0.479 | ||

| Employment | 0.910 | 0.063 | 0.644* | 0.957 | 0.078 | 0.669* |

| Elections | 1.110 | 0.073 | 0.705* | 1.163 | 0.092 | 0.720* |

| Income gap | 1.230 | 0.082 | 0.696* | 1.290 | 0.103 | 0.703* |

| Free press | 1.320 | 0.086 | 0.719* | 1.350 | 0.108 | 0.698* |

| Protection minorities | 0.126 | 0.081 | 0.747* | 1.270 | 0.100 | 0.724* |

| Evaluation nat'l gov | ||||||

| Poverty | 1.000 | 0.841 | 1.000 | 0.850 | ||

| Crime | 0.910 | 0.033 | 0.754* | 0.897 | 0.037 | 0.748* |

| Employment | 0.994 | 0.032 | 0.821* | 0.975 | 0.037 | 0.814* |

| Corruption | 0.866 | 0.030 | 0.774* | 0.864 | 0.034 | 0.787* |

| AMLO | ||||||

| Party id Morena | 1.000 | 0.481 | 1.000 | 0.488 | ||

| Vote AMLO 2012 | 0.839 | 0.080 | 0.435* | 0.807 | 0.091 | 0.434* |

| Feelings AMLO | 9.783 | 0.750 | 0.643* | 9.004 | 0.827 | 0.640* |

| Regresiones | Coeficiente | Err. Est. | Beta | Coeficiente | Err. Est. | Beta |

| AMLO | ||||||

| Religiosity Church attendance | -0.012 | 0.021 | -0.066 | -0.001 | 0.007 | -0.001 |

| Rel on pol | 0.066 | 0.106 | 0.134 | 0.152 | 0.129 | 0.251 |

| Moral values | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.052 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| Economics (left) | 0.120 | 0.141 | 0.148 | 0.114 | 0.143 | 0.156 |

| Democracy | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.012 |

| Ev nat'l gov (neg) | 0.053 | 0.016 | 0.184* | 0.064 | 0.019 | 0.207* |

| Vote for AMLO 2018 | ||||||

| AMLO | 2.035 | 0.165 | 0.814* | 1.708 | 0.169 | 0.749* |

| Religiosity | 0.038 | 0.041 | 0.081 | |||

| Church attendance | 0.022 | 0.012 | 0.068+ | |||

| Rel on pol | -0.021 | 0.179 | -0.017 | 0.131 | 0.190 | 0.095 |

| Moral values | -0.064 | 0.027 | -0.082* | -0.063 | 0.030 | -0.081* |

| Economics (left) | 0.105 | 0.218 | 0.052 | 0.291 | 0.253 | 0.175 |

| Democracy | -0.025 | 0.049 | -0.022 | -0.043 | 0.049 | -0.038 |

| Ev nat'l gov (neg) | 0.026 | 0.027 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 0.030 | 0.050 |

| Catholic | -0.038 | 0.056 | -0.030 | |||

| Protestant/Evangelical | -0.118 | 0.072 | -0.068+ | |||

| Gender | -0.007 | 0.027 | -0.007 | |||

| Age | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.058+ | |||

| Public security perception | -0.001 | 0.028 | -0.001 | |||

| Left-Right | -0.016 | 0.005 | -0.095* | |||

| Urban | 0.017 | 0.051 | 0.010 | |||

| Income | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.012 | |||

| Education | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.028 | |||

| TV news | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.012 | |||

| North | 0.012 | 0.045 | 0.010 | |||

| Central | 0.016 | 0.043 | 0.015 | |||

| South | 0.102 | 0.045 | 0.087* | |||

| Comparative fit index | 0.94 | 0.84 | ||||

| Tucker-Lewisi | 0.93 | 0.82 | ||||

| Root mean square error of approx. | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||||

| Standardized root mean square residual | 0.03 | 0.06 | ||||

| Observations | 1139 | 846 | ||||

Source: Author’s estimations using R, library lavaan (Rosseel, 2012). Mexico 2018 CNEP post electoral survey sample. First observed variables fixed at one for identification purposes. Notes: *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

TABLE A3 Vote choice for Morena, binary logistic models

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est./SE | Est./SE | Est./SE | Est./SE | Est./SE | |

| Party ID Morena | 0.203* | 0.202* | 0.201* | 0.203* | |

| (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.034) | ||

| Vote AMLO 2012 | 0.191* | 0.191* | 0.190* | 0.192* | |

| (0.036) | (0.036) | (0.036) | (0.036) | ||

| Feelings AMLO | 0.064* | 0.065* | 0.064* | 0.064* | |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | ||

| AMLO1 | 0.076* | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| Church attendance | 0.025* | 0.025* | 0.025* | 0.026* | |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | ||

| Religiosity2 | 0.026* | ||||

| (0.010) | |||||

| Religion on politics3 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| (0.004) | (0.004) | ||||

| Rel princip & leader | 0.017+ | 0.017+ | 0.017+ | ||

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |||

| Rel law | -0.001 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.004) | (0.005) | ||||

| Moral values4 | -0.009+ | -0.009+ | -0.008+ | -0.008+ | -0.008+ |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Catholic | -0.043 | -0.045 | -0.047 | -0.041 | -0.039 |

| (0.055) | (0.055) | (0.054) | (0.055) | (0.057) | |

| Protestant/Evangelical | -0.119 | -0.126+ | -0.127+ | -0.121+ | -0.126+ |

| (0.073) | (0.074) | (0.073) | (0.073) | (0.076) | |

| Gender | -0.005 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.006 | -0.009 |

| (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.028) | |

| Age | 0.016+ | 0.016+ | 0.016+ | 0.017+ | 0.022* |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.010) | |

| Public security | -0.006 | -0.006 | -0.002 | -0.005 | -0.002 |

| (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.029) | |

| Left-Right | -0.019* | -0.019* | -0.019* | -0.018* | -0.023* |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Economics5 (left) | 0.005* | 0.005* | 0.005* | 0.005* | 0.006* |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Ev nat’l gov6 (neg.) | 0.018* | 0.018* | 0.019* | 0.019* | 0.018* |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Interest in politics | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.031* |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| Urban | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.023 | 0.031 |

| (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.052) | |

| Income | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Education | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| TV News | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| North | -0.002 | -0.001 | -0.005 | -0.001 | -0.010 |

| (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.045) | (0.046) | (0.047) | |

| Central | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.024 |

| (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.044) | |

| South | 0.087+ | 0.086+ | 0.086+ | 0.088+ | 0.122* |

| (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.045) | (0.046) | (0.047) | |

| Democracy7 | -0.004 | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| Intercept | -0.566* (0.160) | -0.565* (0.160) | -0.615* (0.163) | -0.623* (0.165) | -0.698* (0.178) |

| Observations | 877 | 877 | 880 | 877 | 844 |

| AIC | 860.8 | 860.2 | 861.5 | 860.8 | 855.5 |

| Log-Likelihood | -406.4 | -406.1 | -406.7 | -405.4 | -403.8 |

| McFadden (pseud R2) | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

Source: Author’s estimations using R, routine glm. Mexico 2018 CNEP post electoral survey sample. Robust standard errors. Notes: *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10. Notes: 1 AMLO: PID Morena + voto AMLO 2012 + feelings AMLO. 2 Religiosity: church attendance + religious groups. 3 Religion on politics: religious principles & leader + religious law. 4 Moral values: abortion + gay marriage + gay adoption + death penalty + marijuana. 5 Economics: equality +services taxes + economic growth + private / public enterprises + responsive government. 6 Evaluation national government: poverty + crime + employment + corruption. 7 Democracy: voice of critics + employment + elections + income gap + free press + protection minorities.

TABLE A4 Vote choice in Mexico, 2018, bayesian multinomial probit model

| PAN / Other | PRI / Other | Morena / Other | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef. | Std. Dev. | 2.5 % | 97.5 % | Coef. | Std. Dev. | 2.5 % | 97.5 % | Coef. | Std. Dev. | 2.5 % | 97.5 % |