Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Política y gobierno

versión impresa ISSN 1665-2037

Polít. gob vol.25 no.1 Ciudad de México ene./jun. 2018

Articles

Veto Players and Constitutional Change Can Pinochet’s Constitution be unlocked?

1Profesor colegiado Anatol Rapoport del Departamento de Ciencia Política, Universidad de Michigan. 505 S. State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109. Tel: 734 647 7974. Correo-e: tsebelis@umich.edu.

The paper analyzes the amendment provisions of the Chilean Constitution and finds them unusual in a comparative perspective. It explains their peculiarity from the historical conditions of their original adoption in 1925. It finds the amendment provisions too difficult to overcome, particularly because of the (justified) intentions of complete replacement of the existing (Pinochet) Constitution. As a result, significant amendments cannot be included in the new draft, and most new provisions are likely to be of symbolic nature.

Keywords: organic laws; constitutional amendment; Chile

Este artículo analiza las disposiciones de enmienda de la Constitución chilena y las encuentra inusuales en una perspectiva comparada. Explica su peculiaridad desde las condiciones históricas de su adopción original en 1925. Así pues, encuentra que las disposiciones de enmienda son muy difíciles de superar, particularmente por las (justificadas) intenciones de reemplazar completamente la constitución existente (de Pinochet). En consecuencia, no se pueden incluir enmiendas importantes en el nuevo proyecto, y es probable que la mayoría de las nuevas disposiciones tengan un carácter simbólico.

Palabras clave: leyes orgánicas; enmiendas constitucionales; Chile

The Chilean Constitution is currently under revision. President Bachelet intends to initiate the composition of a completely new constitution, which is an understandable ambition for symbolic reasons (given that the current constitution had been adopted under the Pinochet dictatorship). This paper examines the likelihood of such a replacement, as well as the significance of the modifications that the current constitution is likely to undergo, given the rigidity of the current constitution. In the first section of the paper, I examine the amendment provisions of the current constitution and find them exceptionally rigid and peculiar in comparative perspective. In the second section, I explain their peculiarity from the unusual history of their creation: the political struggles surrounding the adoption of the 1925 constitution. The final section focuses on the likelihood and extent of potential amendments and argues that regardless of goals, only symbolic changes of the current constitution are possible.

Constitutional Amendment under the Pinochet Constitution

John W. Burgess (1890: 137) has argued that a constitution’s amending clause, which “describes and regulates...amending power,” “is the most important part of the constitution” (emphasis mine). The quote both announces the argument and provides the reasons for it. Indeed, the amendment clauses enable future generations to modify the initial document. Tsebelis (2016) has created a game form between two generations of constitution makers. According to his approach, the first generation decides whether to include a particular provision in the constitution, how restrictive (detailed) it should be, and how much it should be locked and protected. The second generation then decides whether it should undertake a constitutional revision given the constitutional content, length and detail of the constitution, the amount of protection that amendment clauses provide, and the current needs of the polity. This game creates a link between the length of a constitution, the frequency of amendments, and the locking mechanisms, which we will investigate with respect to the Chilean Constitution.

With respect to the Pinochet Constitution, Article 127 details two different levels of locking: “The proposed reform will need to be approved in each Chamber by the vote of three fifths of the deputies and senators in exercise. If the reform concerns chapters I, III, VIII, XI, XII or XV, it will need, in each Chamber, the approval of two thirds of the deputies and senators in exercise”. In this section, I study these amendments mechanisms, in order to understand the overall likelihood of constitutional revisions.

Constitutional locking mechanisms

Figure 1 depicts the effects of different supermajority requirements on constitutional change. I use the concept of the constitutional “core” (Tsebelis, 2002; Tsebelis, 2017) to demonstrate the impact that supermajority requirements have on future generations’ ability to alter the Constitution. In any political system, the core is the set of policies or provisions that veto players cannot agree to change. This definition differs from the one presented in legal texts (e.g., Albert, 2015), which consider the “core” to be the articles that cannot be amended regardless of preferences of the constitutional veto players. However, defining the core as dependent not only on the institutions but also on the preferences of the actors can provide a better understanding of the political game of constitutional amendments.

Consider the scenario depicted in Figure 1. If we assume that each one of these seven legislators has his own preferences (depicted by the location of points 1, 2, ..., 7), and that each one of them prefers outcomes that are closer to his preference over outcomes that are farther away, then we can calculate the qualified majority core of this “legislature” as follows. First, suppose that the Constitution specifies that five of the seven members must vote in favor of revisions, in order for them to pass. In this case, the constitutional core lies in the interval between point 3 and point 5 in Figure 1. Indeed, a statu quo provision that lies between player 3 and player 5 cannot be altered with a 3/5ths majority. For any point inside this interval, a blocking minority will always prevent movement away from it. If one considers point 3, for example, it cannot be moved to the left, because 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 will object; similarly, it cannot be moved to the right, because 1, 2, and 3 will object. If the constitution requires a 6/7ths majority for revision, instead of 5/7ths, the core grows, now ranging from point 2 to point 6. In this case, moving to the right of point 2 or left of point 6 will raise objections from two out of the seven members; so, the required 6/7 majority would not be reached. As one might expect, increasing the size of the required supermajority renders it more difficult to revise a constitution. Indeed, under the 6/7ths case, a larger number of provisions become unalterable in this seven-person legislature.

While Figure 1 depicts this dynamic in one dimension, a similar logic applies in two dimensions. Again, assume that the preferences of seven members are two-dimensional and are depicted in Figure 2. Assume also that each one of these legislators prefers points closer to him from points farther away. Figures 2a and 2b illustrate how an increase in required supermajorities increases the size of the core. To create the two-dimensional core in the 5/7ths case, lines are drawn between two players, such that there are two points to one side of the line, and five points either on or to the opposite side of the line (like lines C1C4, C2C5, C3C6, etc.). The core cannot be south of the line C2C6, for example, because five members of the group will replace such a point by its projection on the line itself (which they prefer). Similarly the core cannot be north of the line C2C5, because five members (C2, C3, C4, C5) will pull this point down on the C2C5. Once all such possible lines are drawn, the core is formed at the intersection of all the five-point regions. A similar process is followed to generate the 6/7ths core depicted in 2b. Here, lines are drawn to exclude just one point, instead of two. The resulting intersection is larger than in the 5/7ths case, indicating a larger core. Here again, under the 6/7ths arrangement, one should expect less constitutional revision over time. Figure 2c indicates that the 5/7 core is included in the 6/7 core.

Institutions of Chilean Constitutional revision

The logic of the constitutional core and revision may be extended to the particular provisions of the Chilean Constitution. The Constitution provides for two different paths to constitutional amendment. The first, requiring cooperation between the legislature and executive, is detailed in Article 127:

The Bill of reform will require for its approval [,] in each Chamber [,] the confirming vote of three-fifths of the Deputies and Senators in office.

Article 128 adds to 3/5ths majority an additional requirement:

The Bill which both Chambers approve will be transmitted to the President of the Republic... If the President of the Republic totally rejects a Bill of reform approved by both Chambers and it insists on its totality by two-thirds of the members in office of each Chamber, the President must promulgate that Bill...

Figure 3 depicts the core resulting from this revision procedure. To generate this core, I begin by first generating the two-dimensional cores of each of the two legislative Chambers, using the procedure described earlier. Figure 3a presents these cores in two 13-member legislatures, as created by the 3/5ths majority requirement. Next, Figure 3b presents the joint bicameral core with 3/5ths majority in each Chamber. Since revision requires approval by both Chambers concurrently, the core must grow to include all points located between the two legislative cores. Indeed, any point in this area cannot be defeated by the required 3/5 bicameral majorities: it cannot be moved up or down, because such a movement does not get endorsed by 3/5ths, and it cannot be moved left or right, because one of the two Chambers will disagree. Thus, in Figure 3b, the core stretches between the cores depicted in 3a. Finally, I incorporate the President into the core. Here again, because the President’s approval is required alongside both Chambers, the core must again expand, this time to include all points between the region in 3b and the President’s ideal point, P. This generates the triangle-shaped core found in Figure 3c.

The method of revision depicted in Figure 3 is not the only means by which one may alter the Chilean Constitution, however. As Article 127 states,

If the reform concerns Chapters I, III, VIII, XI, XII or XV it will require the approval of two-thirds of the Deputies and Senators in office. Concerning [matters] not provided for in this chapter, the norms concerning the formation of the law shall be applicable to the process of the Bills of constitutional reform, the quorums specified in the previous paragraph always being respected.

But according to Article 128, if there is disagreement between Congress and the President, the President’s opinion can be overruled by a 2/3 majority of both Chambers. Chile’s Constitution therefore allows for an alternate route to constitutional revision that bypasses the President. Indeed, if the President decides against proposed revisions, the legislature can overrule his/her decision via concurrent 2/3rds majorities in each Chamber of the legislature. Figure 4a presents the 2/3 core of each Chamber (created using the same procedure presented in Figures 2 and 3), and Figure 4b depicts the bicameral core of this alternative procedure. Figure 4b connects those cores of each Chamber (just like in Figure 3b) to account for the majorities requirement. This shaded region is the core of the 2/3rds concurrent majority alternative for constitutional revision.

As Tsebelis (2017) argues, the presence of more than one method of constitutional revision ultimately decreases the size the constitutional core.11 Figure 5a thus depicts this final, smaller core. Indeed, because either of the alternatives allow for constitutional revision, the new core shrinks to the intersection of the two cores depicted in 3c and 4b. In other words, because a provision need only pass through one of the alternatives, provisions located inside one core but not the other can in fact be altered. However, if a policy lies within both cores (i.e., if it lies in the intersection of the cores), it cannot possibly be altered.

However, Chile’s Constitution introduces an additional wrinkle into its constitution revision process: if the President is overridden, he or she can overcome the override through a plebiscite. According to Article 129, the “consultation” of the people through “plebiscite” must proceed as follows:

The convocation to [the] plebiscite must be effected within thirty days following that on which both Chambers insist on the Bill approved by them, and it will be ordered by supreme decree which will establish the date of the plebiscitary voting, which shall be held one hundred twenty days from the publication of the decree if that day corresponds to a Sunday. If this should not be so, it will be held on the Sunday immediately following. If the President has not convoked a plebiscite within such period of time, the Bill approved by the Congress will be promulgated.

The decree of convocation will contain, as it may correspond, the Bill approved by the Plenary Congress and totally vetoed by the President of the Republic, or the questions of the Bill on which the Congress has insisted. In this latter case, each one of the questions in disagreement must be voted [on] separately in the plebiscite.

If the President in fact opts to put constitutional changes up for popular vote, such a choice drastically alters the constitutional core. Because the plebiscite can override any decision made by the legislature, the previous core becomes irrelevant, and the new core now lies along a straight line connecting the President’s ideal point and the public’s ideal point. Figure 5b presents the new core, which replaces the old one.

The constitutional provision found in Article 129 is completely unique in comparative perspective and therefore merits additional attention. According to my analysis, the third alternative (plebiscite) seems to overrule the previous two. This conflict is only apparent. The actual intersection of all three cores is the empty set. Indeed, given that the intersection of the cores of the first two procedures does not include the President, the intersection of the three cores is empty whether the people are located outside the initial triangular core (3/5ths and the President) in the position PL, or inside it in the position PL’. An empty constitutional core implies that there is nothing immune to change inside the Pinochet Constitution. If the President is willing to use the plebiscite specified by Article 129, anything can change, and the agreement between the President and the people will become the new constitution. There is one exception to this rule: if the President and the Congress want to modify the statu quo in opposite directions, but the statu quo is the second best option for both of them (that is, if each one of them prefers the statu quo over the other’s proposal), then the statu quo will prevail. Here is the description of this rule according to Article 128: “In the case that the Chambers do not approve all or some of the observations of the President, there shall be no constitutional reform of the points in dispute, unless both Chambers insist by two thirds of their members in exercise on the part of the project approved by them”.12

The combination of all these constitutional revision articles provides the following synthesis. For an amendment to be successful, it requires 3/5 in both Chambers and the President, (2/3 for articles in Chapters I, III, VIII, XI, XII or XV of the Constitution). In addition, the President can be overruled by concurrent majorities of 2/3 in both Chambers. In case of disagreement between Congress and the President, Congress can either opt for the statu quo (by not approving the President’s proposals) or for a confrontation (by overruling by 2/3) -in which case, the President can send his proposal to a referendum. In the case of disagreement without confrontation, there is no modification of the Constitution; in the case of confrontation, the plebiscite becomes the President’s nuclear option.

The Chilean Constitution provides the President with extraordinary legislative powers. S/he can introduce amendatory observations in legislation, and the Congress can overrule his amendments only by a 2/3 majority. In comparative perspective, these powers do not exist in other Latin American constitutions except for Uruguay and Ecuador (Tsebelis and Aleman, 2005).

However, in terms of constitutional revisions, there is no other Constitution in the world that provides one individual with so much power. The President controls both the question that will be asked and can decide whether to trigger the referendum or not. Consequently, he has complete control of the agenda. The closest one (to my knowledge) is the French Constitution, wherein Article 11 specifies: “The President of the Republic may, on a recommendation from the Government when Parliament is in session, or on a joint motion of the two Houses, published in the Journal Officiel, submit to a referendum any Government Bill.” Notice that in this article, a recommendation by the government is required. In 1962, General De Gaulle decided to modify the Constitution by introducing direct election of the President. He chose the referendum method, but did not receive the required recommendation from the government. The entire legal community (from professors of constitutional law to other legal experts to parties of the opposition) revolted against the initiative, arguing that it was against the Constitution.13

Thus, the Chilean Constitution provides the President with more amendatory powers than the French one. In fact, a President in Chile can replicate De Gaulle’s steps without any founded legal objections. On the basis of Article 129, the President can be completely intransigent vis à vis Congress, and if (s)he is overruled, (s)he can introduce proposals one by one to the populace via referendum. Congress can either opt for the statu quo (and reject the President’s proposals), or it can select confrontation -in which case, the referendums will occur. It is surprising that such a provision exists in a democratic constitution and has not been removed after so many years of democratic rule.14 To understand this peculiarity we need to explore its genesis in the history of Chile’s Constitution and its amendment.

History of amendment provisions

Chile’s modern constitutional history -and its unique plebiscitary provision for constitutional amendment- began with the 1924 efforts to reform the 1833 Constitution in Chile. Prior to the 1920s reform efforts, the Chilean government had become mired in a struggle for power between the legislative and executive branches. For years, Chile was regarded as a “parliamentary republic” (Valenzuela, 1977), but in response to social and economic challenges, newly elected president Arturo Alessandri had attempted to wrest power from the legislature. This struggle stalemated Chilean government (in spite of many urgent challenges facing the country), leading the military to form a junta to demand a resolution to the stalemate. After an internal struggle for control within the military itself, political reform efforts began in earnest in 1925 (Stanton, 1997a: 134).

Military officers placed President Alessandri in charge of reforming the Constitution. This created institutional tension, however, because the 1833 Constitution made clear that constitutional reforms lay within the purview of the legislature’s powers. In response, then, President Alessandri assembled a Consultative Commission by decree, which would be made up largely of democratically elected representatives. The Commission was to be made up of two subcommissions: one in charge of overseeing the constitutional amendment process (and ensuring its popular legitimacy), and the other would decide on the content of the reforms. The Commission met for the first time on April 4, 1925 (Stanton, 1997a: 135).

From the time of the first April meeting of the Commission, Alessandri expressed doubts about its efficacy and usefulness. According to Alessandri, political reform via the constituent assembly was not likely to reach meaningful compromise, nor was the result likely to match his own vision for constitutional reform. After all, conservatives had not yet submitted to the idea that the “parliamentary republic” needed to be done away with. In his own words, “[I] had contracted a commitment with the country that it was necessary to fulfill; but, that same public opinion would have to come to realize that it was not possible to be successful and to achieve that which it desired” (Alessandri, 1967: 166). Thus, instead of moving forward with the popularly elected constituent assembly, Alessandri concentrated reform efforts in a subcommittee of the commission, “Subcommission of Constitutional Reforms” (142).

Unlike the constituent assembly in the Consultative Commission, the Subcommission was full of politicians and other political operatives -particularly representatives of the major political parties in Chile. Thus, while Alessandri seemingly had greater faith in the efficacy of the Subcommission, it was not without its own challenges. In fact, following pro-legislature remarks by one conservative party representative, Alessandri reportedly stormed out of a Subcommission meeting and was ready to halt reform talks altogether. However, according to historians, a number of factors contributed to the ability of the Subcommission to remain intact. First, military leaders arose early in the process as opponents of any return to the “parliamentary republic.” Figures such as General Mariano Navarrete reminded the Subcommission throughout the deliberation process that the military junta itself materialized because of public dissatisfaction with parliamentary predominance. Said Gen. Navarrete, “The Army [...] is horrified at politics [...] but nor will it look on with indifference as the slate is wiped clean of the ideals of national purification, [....] as the ends of the revolutions of the 5th of September and the 23rd of January are forgotten in a return to the political orgy that gave life to those movements” (Chile, Ministerio del Interior, 1925, 454-455). Constitutional reforms, then, should reflect this public desire to roll back the powers of the legislature. Given that the military junta had organized efforts for constitutional reform in the first place, the presences of military officials at the meetings helped to keep conservative and radical party members at the negotiating table. Additionally, the small size and frequent meetings of the Subcommission allowed factions to reach consensus on difficult issues (Stanton, 1997b: 13-17).

While the Subcommission provided Alessandri with a more favorable venue through which to enact constitutional reform, the President encountered a problem with his new focus on the Subcommission: unlike the constituent assembly, the Subcomission lacked popular legitimacy. In response to this problem, then, Alessandri announced his intention in a May 28 manifesto to subject the Subcommission’s proposal to plebiscite. Such a move was not expected by practically any political actor at the time. Indeed, even Alessandri himself did not seem to indicate that a plebiscite was a possibility when he initially convened the Consultation Commission. Opponents too seemed to doubt whether Alessandri was serious about holding a plebiscite: rather than actually drafting an alternative proposal for a plebiscite, Alessandri’s opponents instead focused their energy on public messaging about the constitutional reform process.

Yet while the plebiscite did not appear as part of Alessandri’s original plan, the arrangement ultimately advantaged his view of reform quite well. First and foremost, it was not until July 22 that Alessandri made explicit that the constituent assembly would have nothing to do with the constitutional reform efforts -an announcement he made by angrily “declaring” at a Subcommission meeting that the constituent assembly “has ended”. Said Alessandri, “It is time to finish for once and for all the political comedy, it is time for the President of the Republic to stop being the whipping boy...” (Chile, Ministerio del Interior, 1925). The Subcommission subsequently voted in favor of holding a plebiscite. Given that the plebiscite occurred in August, this gave non-Subcommision reformers only a month to draft an alternative constitution proposal. Unsurprisingly, their proposal was short and unimpressive, in comparison to the Subcommission’s. In fact, many reformers advocated for a boycott of the plebiscite altogether, rather than submit a hasty proposal (Stanton, 1997a: 161). Second, because President Alessandri’s administration was in charge of executing the plebiscite, this arrangement allowed Alessandri to (reportedly) further influence the process via biased language in the plebiscite and even police interference (Vial, 1986: 548). Taken together, in spite of low turnout resulting from the aforementioned calls for boycott, the Subcommission’s Constitution was accepted by a count of 127 483 votes to 5 448 (Bernaschina, 1957: 49).

Ultimately, the ad hoc and combative nature of Chile’s constitutional reform in 1925 led the system to collapse shortly thereafter, in 1927. However, its nonlinear development also resulted in the peculiar plebiscitary provision that remains in Chile’s Constitution today. Indeed, because Alessandri resorted to an extra-constitutional means of “legitimizing” his Subcommission’s constitutional proposal, the plebiscitary provision found its way into the new constitution retroactively. Pinochet retained the provision in his constitutional revisions in 1980, and the provision persists to present day.

Consequences of existing rules on extent of constitutional change

Let us now look at the Chilean amendment rules in comparative perspective, before we move to the consequences they are likely to have on the upcoming constitutional debate and design.

Tsebelis (2016) has applied veto players theory to the amendment provisions of the constitutions of 92 democracies and calculated the constitutional rigidity of these countries. Constitutional rigidity is calculated the following way: if a country has multiple alternative procedures for constitutional revisions, only the first one is evaluated. For this first procedure, the required percentages of the different veto players are summed up. For example, if a country requires a two thirds majority in the legislative chamber and a referendum for a constitutional revision (or adoption of a new constitution), then constitutional rigidity is 2/3 + 1/2 = 1.17. If a country adds constraints to this procedure, a small number (epsilon = .01) is added to the numerical value of constitutional rigidity. For example, if the referendum requires participation of 50 per cent of the population to be valid and must take place within six months from the vote in Parliament, then these two additional constraints raise constitutional rigidity to 1.19. If there is an alternative procedure for constitutional revision, a small number (epsilon = .01) is subtracted from the previously calculated number.

To these rules, one particular provision is added with respect to bicameral countries. A bicameral legislature could be considered as two different chambers, or as the same “legislature”. But the real difficulty of a measure passing through the legislature depends on the ideological distance between the two chambers. For example, if one legislature is controlled by a cohesive right-wing coalition while the other by a cohesive left-wing one, very few measures will be able to pass. So, the ideological distance of the two chambers is included in the calculation.15 These calculations result for Chile in a constitutional rigidity of 1.205.16 This number classifies Chile in the top 20 constitutions (out of 92 that Tsebelis examines) in terms of rigidity.17

Let us focus on this number, because it seems to contradict the conclusion of the first part of this essay: that, if we consider all three alternative methods of constitutional revision, the core of the Chilean Constitution is empty (or, the statu quo according to Article 128). The reason for the difference is that the comparative perspective considers only the first procedure of constitutional revisions in each country, while in this paper we consider all three alternative routes. As Figure 5 indicates, the main reason for the elimination of the core (which is what the cross-country comparison approximates, setting aside the ideological positions of the different actors) is Article 129. As discussed earlier, this provision is unique among democratic countries, and is not likely to be applied by a democratically elected President.

Indeed, application of Article 129 eliminates the constitutional core, and makes a constitutional revision extremely easy (anything between the position of the President and the position of “the people,” however approximated).18 But, if this is the case, why is this procedure not mentioned in the constitutional debate? There are two reasons that I can think of. The first is that it is quite difficult to be used (indeed, Congress can abort such an attempt by voting down the President’s proposal). The second is because a democratically elected president would not be willing to alienate the whole Congress by resorting to a plebiscite to overrule an overwhelming 2/3 majority of both houses of Congress. So, while Article 129 is unlikely that will be used by a democratic President, it can be extremely useful to one who is willing to ignore and marginalize Congress. Article 129 can enable such a president to perform a constitutionally legitimate revision. The reader is reminded of the French case, where only the approval by the people eliminated all constitutional objections.

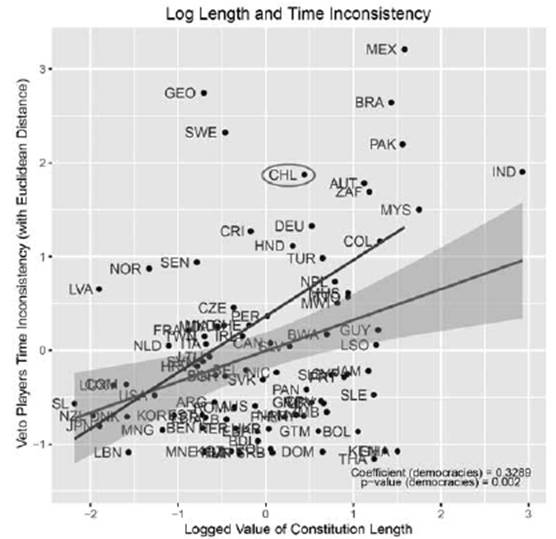

Another interesting indicator of constitutions is their “time inconsistency” (Tsebelis, 2017), that is, the difference between the institutional expectation of revisions and the actual revision frequency. One would expect more rigid constitutions to be revised less frequently, because the hurdles of a revision are higher. Yet, the founders of the constitution must make multiple decisions: they have to decide first whether to include a subject matter in the constitution, and then how detailed their prescriptions should be. The final decision is over how much they should lock these prescriptions. The future generations then have to decide if they want and can overcome these restrictions and amend the constitution. The longer a constitution is, the more likely that future generations will find some prescriptions objectionable or outdated. On the other hand, the more locked the constitution, the less likely successful amendment attempts will be. Time inconsistency is a summary indicator of the conflict between constitutional rigidity and amendment frequency. Tsebelis (2017) attributes time inconsistency to the length of a constitution: it is as if the founders of constitutions want to include many provisions and lock them, in order to prevent future generations form altering their choices. As Waldron says (1999: 221-222):

To embody a right in an entrenched constitutional document is to adopt a certain attitude towards one’s fellow citizens. That attitude is best summed up as a combination of self-assurance and mistrust: self-assurance in the proponent’s conviction that what he is putting forward really is a matter of fundamental right and that he has captured it adequately in the particular formulation he is propounding; and mistrust, implicit in his view that any alternative conception that might be concocted by elected legislators next year or in ten years’ time is so likely to be wrong-headed or ill motivated that his own formulation is to be elevated immediately beyond the reach of ordinary legislative revision.”

Looking at the Chilean Constitution, we find that it is in the top 10 constitutions in terms of the time-inconsistency indicator; that is, it changes very often, despite the locking mechanisms included in it. Figure 6 provides a visual comparison of length and time inconsistency of the Chilean Constitution with that of other democracies. Despite the fact that time inconsistency is high, Chile does not appear to be an outlier in this figure. However, the impression is misleading, because the figure (for comparative purposes) includes only the formal Chilean Constitution of 25 649 words. However, a closer look at the constitution indicates that, in Article 63, an intermediate level of legislation is created: “organic laws”. This kind of law requires a vote by 4/7ths in each Chamber of the bicameral legislature, and the approval of the President of the Republic. The Constitution refers to “organic laws” 69 times, particularly (but not exclusively) in articles 12, 27, 37, 40, 43, 46, 48, 52, 60, 61 and 63.

Chile is not the only country with “organic laws,” that is, laws with status between the Constitution and ordinary laws. There are over than 25 democracies (in the 92 countries Tsebelis [2017] examines) with legislation that requires more restrictive passage conditions than ordinary laws. France, Belgium, Spain, and Denmark provide examples in Europe, and Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia provide examples in Latin America. However, Chile requires the passage of such laws in a wide range of specific areas (69 mentions in the Constitution). In addition, while most countries require an absolute majority for the passage of such laws19 (Brazil; in final passage in Spain; plus approval by the Constitutional Court in France), the Chilean restrictions are overwhelming.

Consequently, there not only two but three different levels of locking included in the Constitution. Chapters I, III, etc. require a 67 per cent approval by both chambers. Much of the constitution requires a 60 per cent approval. Finally, “organic laws” require a 57 per cent approval.

Organic laws are not included in the formal constitutional text. Substantively, however, they are almost as much locked as the rest of the constitution. Yet in spite of this importance, organic laws have had a fairly short history in the Chilean Constitution. In the 1925 Constitution, organic laws are mentioned explicitly only once, in Article 72.8. There, organic laws simply refer to the agency-specific rules governing conduct among low-to mid-level bureaucrats, and no mention is made about supermajority requirements. The only other de facto mention of organic laws occurs in Article 44.5, where pension reform is delineated as a policy change requiring concurrent 2/3 majorities for passage. Rather than the 1925 Constitution, then, contemporary organic law in Chile derives from the 1980 Pinochet Constitution. There, as noted earlier, organic laws (and the accompanying 4/7 majority requirement) pertain to many different issues and appear in a large number of articles (see the list above).

If one considers these organic laws as part of the Constitution, the length of Chile’s Constitution becomes overwhelming. Time inconsistency also explodes if one considers the revisions not only of the formal constitutional text but also of the organic laws. A detailed study of Chilean organic laws and their modifications is necessary to provide numerical values to these arguments; however, one can expect that the position of Chile should be significantly to the northeast of the graphed line, since both length and time inconsistency will be significantly higher.

What are the consequences of this analysis for the upcoming constitutional revisions? When a country attempts to revise its constitution, it is typically a sign that the veto players have moved away from the previous constitutional core. This is likely the case in the Chile today. Indeed, for symbolic reasons, the government of Chile not only wants to make major revisions to its Constitution, but it wants to replace the existing Pinochet Constitution entirely. To do so, they must obtain concurrent 2/3rds majorities in both Chambers of the legislature and the President. The exact procedure has not been spelled out yet, but the 2/3 concurrent majorities in both houses and the President have to be an essential ingredient of the procedure.

A one-dimensional depiction of this dynamic best captures the intuition of public opinion shifts and constitutional change. Figure 7a depicts a 7-member legislature, with a 5/7ths and 6/7ths core. In Figure 7b, members 3 through 7 have moved to the right, changing the core of the Constitution as depicted. In the Chilean context, this movement can be thought of as a movement away from the Pinochet Constitution, in favor of a new one. When the movements in 7b occur as depicted, a new set of statu quo provisions become alterable. This new set is highlighted at the top of 7b. However, as the figure underscores, a new set of statu quo provisions does not exist when a 6/7ths majority is required for revision of the Constitution. In this case, the previous 6/7ths core is contained within the new one. This comports with the general argument presented earlier, that larger required majorities render a constitution more difficult to change. Put simply, the larger cores resulting from large supermajority requirements render a larger set of status quo provisions immoveable. Additionally, Congress may opt (via Article 128) to disapprove Presidential amendments. As I described in the previous section, this strategy prevents the President from using the plebiscite option and selects the statu quo as the final outcome.

This analysis sheds important light on the present situation in Chile. As noted above, reformers in Chile have opted to make use of the 2/3rds concurrent legislative majorities and President a requirement for constitutional revision. Recall, however, that this option is not the only means by which the Chilean Constitution may be altered. Indeed, Chile’s Constitution can be amended with 3/5ths concurrent majorities in the legislatures, plus the approval of the president. As Figure 7 suggests, under the smaller majority in 7a, a change can occur; however, under the larger majority in 7b, a change is not possible.

By opting for the concurrent 2/3rds majority option, Chilean Constitutional reforms have essentially moved their cause from the top of Figure 7 to the bottom. If this is the case, I argue that successfully supplanting the Pinochet Constitution will be highly difficult and may well fail to transpire.

Looking back at the important constitutional revisions of Chile will shed some light to this argument. As I demonstrated in Figure 6, the Chilean Constitution is extremely high in time inconsistency. It changes a lot, despite its locking. So, why care about the formal rules, when in the past despite these rules the Constitution has been amended so frequently?

First of all, note that many of these modifications were, to use Fuente’s (2015: 104) wording, “partial reforms [...], including advancing some civil and social rights, democratizing municipal elections and Supreme Court appointments, and reducing the presidential term from eight to six years”, But, the most important point is the following: all of these amendments were approved by both the Left and the Right. When major reforms lacked the support of the right, failed to get the required majorities (1992: 94, 95).

However, according to all accounts, there have been two extremely significant revisions to the constitution, in 1989 and in 2005. The first was before the transition to democracy. It was produced by a nonpartisan commission that included academics and constitutional scholars, who were charged with proposing some changes (created by the Concertación and RN) and approved by a referendum. These changes included both substantive and procedural amendments. The substantive amendments removed the President’s power to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies, and they reduced the presidential term from eight years to four. The reforms also modified the powers of the Constitutional Tribunal, stripped the military of its majority in the National Security Council, subject the armed forces to “organic laws.” Laws allowing for the dissolution of parties supporting “totalitarian doctrines” were also repealed. The procedural amendments reduced the qualified majority thresholds: for constitutional revision from 2/3 to 3/5; for organic laws from 3/5 to 4/7. The number of elected senators was increased from 26 to 38, so that the significance of appointed senators was reduced. Mayors were (indirectly) elected, instead of appointed (Fuentes, 2006: 17).

According to Fuentes (2006:18):

The then-opposition leaders saw that they should focus their efforts on ensuring opportunities for future constitutional reform (emphasis added). In this sense, the strategic calculation of the negotiators was not to seek a reform of all the negative aspects of the 1980 Constitution, but rather simply to try to maximize the opportunities for future efforts at reform. This they did in two ways: by reducing the quorums necessary for introducing reforms and increasing the number of senators in order to reduce the relative strength of the non-elected senators (Andrade, 1991, Heiss and Navia; forthcoming). This was clear in April 1989, when the then-Interior Minister Carlos Cáceres presented the reform package that would be put up for the plebiscite once negotiations with the opposition concluded.

The second major amendment enterprise began in 2000 and ended in 2005, covering 58 topics of the Constitution (Fuentes, 2015: 111). These involved:

repeal of the institution of designated and life senators, a change in the composition of the National Security Council and a reduction in its powers, restoration of the president of Chile’s power to remove commanders-in-chief of the armed forces and the director of the Carabineros (the uniformed national police force), a modification of the composition of the Constitutional Tribunal, an increase in the powers of the Chamber of Deputies to supervise the executive, a reduction in the presidential term of office from six to four years without consecutive re-election, a reform of the constitutional states of exception in order better to protect rights, and the elimination of special sessions of Congress (Fuentes, 2015: 100).

Again, the long negotiations had the persuasion of the Right as the goal, and significant concessions were made to achieve this goal. The Right accepted the elimination of appointed and life senators, in exchange for the reduction of the powers of the President. As Fuentes summarizes (2015: 113):

This involved increasing the oversight powers of the Chamber of Deputies, allowing a political minority to request accountability from ministers; increasing the possibility of establishing investigative commissions in the Chamber of Deputies; strengthening the Constitutional Tribunal’s powers by fostering its role as a veto actor in the political process; allowing the Senate to intervene in the appointment of authorities (for example, ambassadors); and reducing the executive’s capacity to control budgets. These five issues were explicitly set out in the original proposal put forward by the Alianza in July 2000. The final agreement included the first three points, significantly increasing the power of Congress to oversee the executive. It is interesting to note that the Alianza linked the elimination of designated and life senators with the need to preserve an “adequate balance between political powers” (Historia de la Ley, 2005, 31). This would be achieved through greater participation in the appointment of Constitutional Tribunal ministers, who, in most cases, would have to be approved by the Senate.

This compromise was possible because Chile had reached an extraordinary point in its political history, where the two major coalitions were of approximately equal strength, so that, behind the “veil of ignorance” could focus on amendments improving the institutions of the country as opposed to partisan goals.

From this short institutional history, we can confirm the two conditions that emerged from the institutional analysis of this article. Successful constitutional amendments require: 1) the statu quo to be located outside the constitutional core and 2) the required majorities specified by the constitution (3/5 of each Chamber, or in the current procedure of adoption of a new constitution 2/3 of each Chamber) make an agreement of the Right and Left necessary.

Given sharp divisions between the Right and Left in Chile, the set of provisions that meet these criteria today may be largely symbolic in nature. This assertion is supported in a working paper by Navia and Vedugo. In the paper, the authors find that, while a majority of citizens in Chile support replacement of the Pinochet Constitution, their motivation for doing so is based primarily on a desire for increases in social “rights”. These include symbolic rights to “healthcare, abortion, labor rights, and education” (Navia and Verdugo: 16). I call these kinds of provisions “symbolic”, because such provisions do not function like constitutional rights in the traditional sense. That is, they are not protections against the government, and including them in constitution does not automatically render the government able to deliver on them. Providing universal education, for example, requires a great deal of money, and if the government lacks the revenue, it cannot fulfill its constitutional “obligation” in education.

Consequently, inclusion of these rights in the text will necessarily be an invitation to judicial activism: courts will decide whether these rights are observed or not. However, there will be no means for enforcement of these rights. As the apocryphal quote attributed to U.S. President Andrew Jackson states: “Well, John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it”.20 A possible second step of this procedure may be a reaction of the political system to an abundance of court judgments against the government. In this case, court judgments would be a signal for the necessity of such a decision. If this decision requires a simple majority it may be possible; if, however, an organic law is constitutionally required, such a decision may be difficult to materialize.

Conclusions

The constitutional revision in Chile is desirable for symbolic reasons. However, the constraints included in the Pinochet Constitution are very difficult to overcome. Modification of substantive provisions of the current Constitution will require cooperation among the different political forces of the country. The analysis in this article indicates that there are two world-wide originalities included in the current Constitution. The first is that Article 129 eliminates the constitutional core and makes a constitutional revision very easy to achieve, by a plebiscite proposed by the President alone. However, no political actor in Chile advocates the use of this procedure. The second is the wide use of organic laws and the requirement of extremely high qualified majorities for their adoption (4/7 according to Article 63, when constitutional revisions require 3/5). This article prevents the government from its primary function, which is policymaking.

Both provisions do not seem very functional, or very democratic. The fact that Article 129 has been used only once in the history of Chile (to adopt the Constitution that introduced these restrictions for the first time) does not mean that Article 129 cannot be used to legitimize a departure from the democratic order. It would be productive if discussions about the content of the new Constitution revolved around Articles 63 and 129 (as well as the excessive references to organic laws, particularly (but not exclusively) in articles 12, 27, 37, 40, 43, 46, 48, 52, 60, 61 and 63. Further reduction of the 4/7 qualified majority requirement would also improve democratic decisionmaking in the country. These changes will significantly modify the constitutional order of the country. Therefore, it would be important for political parties to try to reach a consensus on these issues.

These proposals further extend the modifications introduced in the 1989 constitutional revision. Indeed, they reduce the powers of the President further (concerning an occasion that has very low probability to materialize), and reduce further the frequency of stringent requirements for organic laws. In order to be achieved, serious attempts for negotiations and compromise between the Left and the Right must be undertaken.

The discussions involving social rights may have symbolic value, but we have to remember that the constitution of a country is not the place to include good ideas, but workable compromises. Consequently, and given the significance of Article 63 for the governability of the country, the focus of the political forces should be in the reduction of the qualified majorities required for organic laws in this article, or the scope of use of organic laws prescribed in the current Constitution.

Referencias bibliográficas

Albert, R. (2015), “The Unamendable Core of the United States Constitution”, Boston College Law School Faculty Paper, pp. 13-40. [ Links ]

Alessandri Palma, A. (1967), Recuerdos de gobierno: Administración 1920-1925, vols. I y II, Santiago de Chile, Editorial Nascimento. [ Links ]

Andrade Geywitz, C. (1991), Reforma de la Constitución Política de la República de Chile de 1980, Santiago de Chile, Editorial Jurídica de Chile. [ Links ]

BCN (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile) (2005), Historia de la ley 20 050 que introduce diversas modificaciones a la Constitución Política de la República, Santiago de Chile, BCN. [ Links ]

Bernaschina, M. (1957), “Génesis de la Constitución de 1925”, Anales de la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales, 3(5), enero-diciembre 1956, pp. 46-65, disponible en: http://www.analesderecho.uchile.cl/index.php/ACJYS/article/view/6029/5895 [fecha de consulta: 5 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Burgess, J.W. (1890), Political Science and Constitutional Law, 2 vols., Boston y Londres, Ginn & Company. [ Links ]

Fuentes, C. (2006), “Looking Backward, Defining the Future: Constitutional Design in Chile 1980-2005”, ponencia presentada en la CII Reunión Anual de la American Political Science Association, Filadelfia, 31 de agosto-3 de septiembre. [ Links ]

Fuentes, C. (2015), “Shifting the Statu Quo: Constitutional Reforms in Chile”, Latin American Politics and Society, 57(1), pp. 99-122. [ Links ]

Heiss, C. y P. Navia (2007), “You Win Some, You Lose Some: Constitutional Reforms in Chile’s Transition to Democracy”, Latin American Politics and Society, 49(3), pp. 163-190. [ Links ]

La Porta, R., F. López-de-Silanes, C. Pop-Eleches y A. Shleifer (2004), “Judicial Checks and Balances”, Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), pp. 445-470. [ Links ]

Longaker, R.P. (1956), “Andrew Jackson and the Judiciary”, Political Science Quarterly, 71(3), pp. 341-364. [ Links ]

Lijphart, A. (2012), Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-six Democracies, New Haven, Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Lorenz, A. (2005), “How to Measure Constitutional Rigidity: Four Concepts and Two Alternatives”, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 17(3), pp. 339-361. [ Links ]

Lutz, D.S. (1994), “Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment”, American Political Science Review, 88(2), pp. 355-370. [ Links ]

Ministerio del Interior (1925), Actas Oficiales de las Sesiones celebradas por la Comisión y Sub-comisiones encargadas del estudio del Proyecto de Nueva Constitución Política de la República, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta Universitaria. [ Links ]

Navia, N. y S. Verdugo (2016), “Crisis and Expansion of Rights as Drivers of Constitutional Moments in Emerging Democracies: The Case of Chile, 1990-2016”, manuscrito, Nueva York. [ Links ]

Stanton, K.A. (1997), “Transforming a Political Regime: The Chilean Constitution of 1925”, tesis doctoral, Department of Political Science-University of Chicago. [ Links ]

Stanton, K.A. (1997a), “The Transformation of a Political Regime: Chile’s 1925 Constitution”, ponencia presentada en el XX Congreso Internacional de la Asociación de Estudios Latinoamericanos, 17-19 de abril, Guadalajara, México. [ Links ]

Tsebelis, G. (2002), Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work, Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Tsebelis, G. (2016), “Constitutional Rigidity: A Veto Players Approach”, manuscrito, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, disponible en: http://sites.lsa.umich.edu/tsebelis/wp-content/uploads/sites/246/2015/03/Constitutional-Rigidity_Total.docx [fecha de consulta: 5 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Tsebelis, G. (2017), “The Time Inconsistency of Long Constitutions: Evidence from the World”, European Journal of Political Research, doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12206. [ Links ]

Tsebelis, G. y E. Alemán (2005), “Presidential Conditional Agenda Setting in Latin America”, World Politics, 57(3), pp. 396-420. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, A. (1977), Political Brokers in Chile: Local Government in a Centralized Polity, Durham, Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Vial, Gonzalo (1987), “La Constitución de 1925”, Historia de Chile, 1891-1973, vol. III, Santiago, Editorial Santillana del Pacífico. [ Links ]

Waldron, J. (1999), Law and disagreement, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Received: February 27, 2017; Accepted: June 07, 2017

texto en

texto en