Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Política y gobierno

versión impresa ISSN 1665-2037

Polít. gob vol.23 no.1 Ciudad de México ene./jun. 2016

Research notes

Demonstrations, occupations or roadblocks? Exploring the determinants of protest tactics in Chile *

* Estudiante de doctorado en Ciencia Política en la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile y patrocinado por el Centro de Estudios de Conflicto y Cohesión Social (COES), Instituto de Ciencia Política, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Av. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul (campus San Joaquín), Santiago, Chile. Tel: +56 99 84 39 06 89. Correo-e: rmmedel@uc.cl.

** Profesor asistente del Instituto de Sociología de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile e investigador asociado del COES, Instituto de Sociología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Av. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul (campus San Joaquín), Santiago, Chile. Tel: +562 23 54 46 51. Correo-e: nsomma@uc.cl.

Collective protest grew recently in Chile, yet we know little about the characteristics and determinants of the tactics employed. By examining more than 2 300 protest events between 2000 and 2012, we explore the determinants of the adoption of four types of tactics: conventional, cultural, disruptive and violent. Multivariate regression models show that: 1) protests against the State elicit conventional tactics, but protests against private companies elicit disruptive and violent tactics; 2) workers "specialize" in disruptive yet non-violent tactics; 3) the presence of formal organizations in the protest increases conventional tactics and decreases disruptive and violent tactics, and 4) protest events with a smaller number of participants are more likely to have disruptive and violent tactics than more massive events.

Keywords: collective protest; tactics; social movements; Chile

La protesta colectiva creció recientemente en Chile, pero sabemos poco sobre las características y los determinantes de las tácticas empleadas. Analizando más de 2 300 eventos de protesta entre 2000 y 2012, exploramos los determinantes de la adopción de cuatro tipos de tácticas: convencionales, culturales, disruptivas y violentas. Las regresiones multivariadas muestran que: 1) la protesta contra el Estado suscita tácticas convencionales, pero la protesta contra empresas privadas suscita tácticas disruptivas y violentas; 2) los trabajadores se "especializan" en tácticas disruptivas pero no violentas; 3) la presencia de organizaciones formales en la protesta aumenta las tácticas convencionales y disminuye las tácticas disruptivas y violentas, y 4) los eventos con un menor número de participantes exhiben tácticas disruptivas y violentas en mayor medida que los eventos más masivos.

Palabras clave: protesta colectiva; tácticas; movimientos sociales; Chile

One of the issues that has stirred up considerable interest in the literature about social movements in recent years is the one regarding tactics of collective protest (Taylor and Van Dyke, 2004). When a group of people decide to publicly express its dissatisfaction with the authorities, why does it sometimes use peaceful and conventional tactics, such as an organized demonstration in a plaza; and other times violent and rowdy ways, for example destroying public or private property? Why are tactics with a high symbolic content, such as a theater performance ridiculing a hated politician, sometimes used? And why is it that it is decided, other times, to alter normal daily functioning, for example by taking over a school or factory or blocking a highway?

This article explores the determinants of collective protest tactics in Chile between 2000 and 2012. For this purpose, we use a database of more than 2 300 protests built with the methodology of protest event analysis (PEA from this point forward), an approach increasingly used in several parts of the world although still scarcely used in Latin America. The pea consists of the construction and statistical analysis of a database with information about the protest events that take place in a space and period of interest (Koopmans and Rucht, 2002; Kriesi et al., 1995). This allows to understand which tactics are used more or less under different conditions, and eventually to explain these variations.

Within the research about social movements, the study of protesting tactics is important for several reasons. First, the use of "non-institutionalized" forms of action is one of the main criteria to differentiate social movements from other political actors, such as parties or interest groups (Tarrow, 1998; but see Goldstone, 2003 for a different view). Second, the tactics can affect the possibility for social movements to reach the objectives they propose (Morris, 1993). For example, some studies show that disruptive and violent tactics can help movements of popular groups to become successful, while other studies suggest that violence generates a negative reaction from the authorities that can end up disarticulating the movements (Giugni, 1998). Third, tactics influence the movements image among the public opinion, which can impact the extent to which the movement can obtain more resources and supporters in the future. Finally, tactics can reflect the identities, cultural frameworks (Jasper, 1998) and organizational characteristics (Morris, 1981) of the movements. Because of all this, few aspects are as central for the formation and unfolding of movements as their tactics.

Chile constitutes an interesting study case of protest tactics in the Latin American context. Since transition to democracy in 1990 and until the mid-2000s, Chile was characterized by low levels of protest and social mobilization, in comparison to other more active countries like Ecuador, Venezuela, Argentina or Bolivia (Silva, 2009). Since 2006, however, protest increased considerably as a result of the secondary school students' mobilizations (Donoso, 2013), and in the following years it was extended to a diversity of groups that were previously demobilized. Here we will not perform longitudinal analyses or study how the relationships between the tactics and their determinants change throughout time; our intent is more of an exploratory nature. However, our data, which range from 2000 to 2012, allow to capture these processes of expansion of protest.

Although the Chilean results obviously cannot be extrapolated to the rest of Latin America, they can offer some leads in this sense. First, like Argentina, Bolivia or, at its time, Venezuela, a good part of protest in Chile is motivated by dissatisfaction with the social costs of neoliberalism and the negative externalities of companies (Silva, 2009). Second, in the last decade, Chile has experienced massive students' protests that exhibit a new repertoire of dramaturgic tactics with a strong symbolic content. This is interesting given the force that student movements have attained in countries like Colombia or Mexico. Third, Chile is one of the countries in the region where digital technologies have been taken advantage of more intensely for the display of new protest tactics (Somma, 2015), which is why their study can anticipate some trends in regard to other countries that are more backward in this aspect.

Conceptualizing protest tactics

Although the modern study of social movements can be dated back to the 1920s in the Chicago school, with the theory of collective behavior (Park and Burgess, 1921), the first systematic studies about protest tactics were performed only at the end of the 1970s (Taylor and Van Dyke, 2004). The main approaches before the 1970s -essentially mass society (Kornhauser, 1969), structural functionalism (Smelser, 1962) and collective behavior (Turner and Killian, 1957)- emphasized the irrational and pathological aspects of protest and gave little importance to the rational and strategic component of social movements. By ignoring these components, the question of why rational and strategic actors decide certain tactics instead of others could not be asked.

Since the 1970s, two theoretical currents arose that allowed opening the field of interest towards protest tactics: the theory of political process (Tilly, 1978; McAdam, 1983; Tarrow, 1998; McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly, 2001) and the theory of resource mobilization (McCarthy and Zald, 1977; Jenkins, 1983). The first emphasized mainly the external factors of social change and the transit from traditional repertoires of protest to modern repertoires (Tilly, 1978). The latter incorporated the interest over internal determinants of the movements themselves and their influence on the tactical display (McCarthy and Zald, 1977; Morris, 1981). What these two views share is that they both understand social movements as rational, organized and strategic forms of action.

In the 1980s the "new social movements" approach arose in Europe (Touraine, 1981; Cohen, 1985; Offe, 1985), which sought to understand the forms of mobilization that arose in the transition from an industrial society to a post-industrial society. These authors considered that the concept of "repertoires of contention", coined by the theory of political opportunities, was limited. When referring to strategically oriented movements, this concept left little room to consider the "new movements", mobilized more by identity building and by the challenging of cultural frameworks (Cohen, 1985; Touraine, 1981).

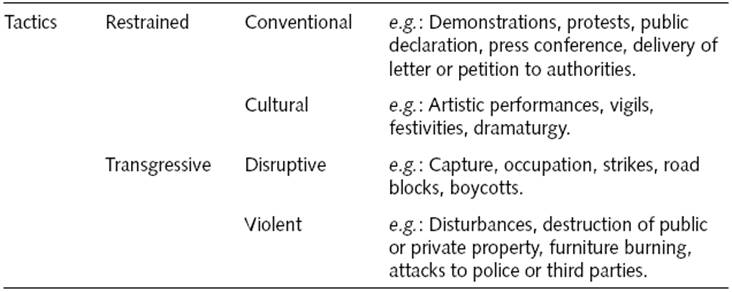

Thanks to these debates, there is, today, a significant consensus in the literature regarding the distinction between two large types of protest tactics. The restrained tactics (also called "non-confrontational") are peaceful, legal and relatively organized. The transgressive (or confrontational) tactics, as their name implies, are directed at interfering in the daily routines of the population or the authorities, are illegal or semi-legal, and can occasionally become physically violent or dangerous both for activists and for pedestrians, for the authorities questioned, or for police forces (Van Dyke, Soule and Taylor, 2005; McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly, 2001; McAdam, 1983).

Although this offers a bulk distinction between types of tactics, more recently the need to distinguish sub-groups within each group has been suggested (Van Dyke, Soule and Taylor, 2005; Walker, Martin and McCarthy, 2008). In terms of transgressive tactics, the seminal study in this regard is that by Koopmans (1993), who establishes a distinction between non-violent and violent confrontational tactics (differentiating the latter between minor violence and direct violence). His results show important differences in the use of these tactics in function of internal and external determinants of movements throughout time.

Other later studies have also shed light on violent tactics, understood as a special manifestation within transgressive tactics. Mainly, the relationship between state repression and the surge of protest violence has been studied (Della Porta, 1995; Koopman, 1997).

In turn, restrained or "non-confrontational" tactics have also been studied in more specific manifestations, primarily through studies that differentiate conventional tactics from cultural tactics. Cultural tactics have been examined at first as internal tactics, insofar as they had the function of reinforcing the internal solidarity of the groups and the identity of the protesters (Kriesi et al., 1995). However, recent studies maintain that cultural tactics not only have internal consequences but also external ones, so they must be considered as an additional repertoire for action at the time of seeking a concrete political objective (Kimport, Van Dyke and Andersen, 2009).

Thus, restrained tactics comprise the "conventional" and the cultural ones. The conventional ones -which, as we will see, are the most frequent in Chile- include demonstrations, manifestations, public gathering of signatures or money for certain collective causes, and public declarations addressed to the authorities. "Cultural" tactics reflect an evident intention to symbolize or represent some element of the collective cause through artistic or graphic media, or through a more sophisticated coordination of actions of those present than the habitual. They include, for example, theater or artistic representations by amateurs or professionals, "bicycle rides", vigils and others.

In turn, transgressive tactics are divided into "disruptive" and "violent". The disruptive ones interfere with daily routines, and include civil disobedience, labor or student strikes, taking over or occupying buildings and blocking routes. The "violent" ones include, for example, lighting fire to vehicles, properties or buildings, destroying public or private properties, looting, or violent confrontations with counter-protesters or police forces (Taylor and Van Dyke, 2004).

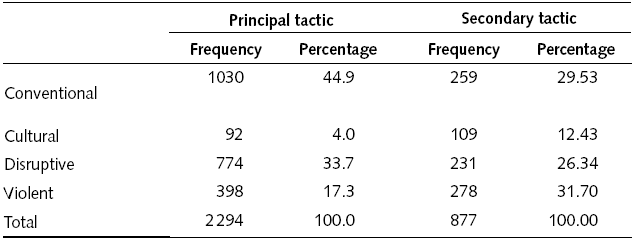

These new distinctions are relevant for our purposes because, as we will see further on, the determinants of conventional tactics are not necessarily the same than those of cultural tactics, and the same happens between disruptive and violent tactics. In this regard, we are interested in highlighting that analyses of protest events such as ours allow observing more than one type of tactic at each event. Thus, for example, a conventional protest event could be associated with another cultural tactic. This is why we consider both principal tactics and secondary tactics in the analyses (events with more than two types of tactics are minimal). As we will see, there are certain tactics that tend to be employed more as secondary rather than as principal ones.

Determinants of protest tactics

Which factors explain the presence or absence of the different types of tactics discussed above in collective protests? We have taken into account four factors that we have considered as central for the study of the tactics, based on the literature, which are: targets of the protest, groups that protest, presence or absence of formal organizations, and number of participants.

Targets of the protest

The "target of the protest" refers to the entity to which the protest is explicitly directed. Until two decades ago, it was assumed that the State was the sole target to which social movements were directed to obtain their demands. This happened because of a strong influence from the theory of the political process, and in particular from Charles Tilly's explanation about modern social movements that arise under the protection of the construction of national States (Tilly, 1978, 1995; McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly, 2001; Tarrow, 1998; McAdam, 1982). However, several studies recently began to dispute the "state-centric" premise, when it was clear that social movements often direct their darts to other entities such as private companies, universities, international organisms or others (Manheim, 2001; Pellow, 2001; Van Dyke, Soule and Taylor, 2005; King and Pearce, 2010). For example, a third of the protests in the United States point to targets different than the State, such as corporations and educational institutions (Walker, Martin and McCarthy, 2008). Today, several "anti-corporate movements" are focused on the social and environmental damage caused by large corporations of contemporary capitalism (Pellow, 2001). In Latin America, the exploitation of natural resources (such as water, forests or minerals) presented during the second half of the 20th Century an incentive for the labor protest against foreign companies, to which the ecologist and indigenous protests are summed today.

The targets of protest are not given or evident objects. According to the theory of collective action frameworks (Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford, 1986; Benford and Snow, 2000), they are the result of a collective process during which movements combine evidences, justifications and institutions of various types to end up attributing the responsibility of dissatisfaction to a particular actor -national or local actors, companies or others. The collective action frameworks allow identifying not only those presumed to be responsible, but also the actors that could perform in such a way as to solve the collective problem. For example, a private company could be perceived as the one directly responsible for pollution in a community, but if the State is perceived as the entity capable of regulating the emissions of that company, the protest can be also directed at state authorities.

Walker, Martin and McCarthy (2008) provide the most solid theory up to date to understand the impact of the targets of the protest in the tactics employed. Their premise is that the institutional strengths and weaknesses of the different targets shape the type of tactics that will be directed at them. For example, since States aspire to obtain the monopoly of legitimate violence (Weber, 1964) and concentrate large coercive capacities, the violent tactics against them can end up in severe repression that entails high costs for activists. This does not happen for non-state institutions, which do not have this coercive capacity directly and lack the legitimate apparatus to impose repression. And the few responses that non-state institutions do have access to -such as massive layoffs by companies or student expulsion by universities- are scarcely used since they severely damage their image and legitimacy. Consequently:

Hypothesis 1: The protest events that target the State exhibit restrained tactics (conventional and cultural) to a greater extent than the events with non-state targets.

Hypothesis 2: The events with non-state targets exhibit transgressive tactics (disruptive and violent) to a greater extent than the events with State targets.

Participating groups

There is not full agreement in the literature about the possible relationships between the groups that protest (e.g., workers, students, indigenous people or environmentalists) and the tactics that they employ. In part, the difficulty stems from the fact that the social groups do not necessarily act in a cohesive manner and under a unified leadership, so that their actions are not completely predictable. To address these complexities, we propose interpreting the groups of protesters from two large analysis axes: their relationship with the productive sphere and their level of political capital.

With regard to the first, McAdam (1982) and Schwartz (1988) argue that the groups constituted around economic production (such as workers or business people) have the ability to exert "negative inducers". This means that they can occasionally opt to abstain from fulfilling their daily productive functions with the aim of generating damage to the authorities (and eventually to society as a whole), and in this way exert pressure to obtain their demands. These groups should appeal to non-violent disruptive tactics such as a labor strike or blocking the supply of basic goods.

On the other hand, groups with high political capital (therefore an easy access to the political system and high legitimacy in public opinion) have much to lose, which should make them resistant to violent tactics (Bernstein 1997; Walker, Martin and McCarthy, 2008). In turn, this should make them more prone to conventional or cultural tactics, which allow them to maintain their good reputation in the political system and public opinion, and which in general are not perceived as threatening (Crozat, 1998). However, groups with low political capital would have less to lose and more to gain, which could persuade them to use violent tactics (Piven and Cloward, 1979; Van Dyke, Soule and McCarthy, 2001).

These relationships are not automatic. In order for groups with different levels of political capital and insertion into the productive sphere to prefer certain tactics to others, it is generally necessary for "framing" processes to operate, where these tactics are defined as the most adequate and viable (Benford and Snow, 2000). These processes are not linear and can be crossed by internal conflicts and disagreements, as Benford (1993) showed for anti-nuclear groups. In addition, the collective identities that permeate different groups impact the selection of tactics, whether by making some more attractive or others more repulsive (Polletta and Jasper, 2001).

Although various groups protest in Chile, we focus on employed workers (public and private) as reference to establish their differences with regard to other groups. We chose workers, first, because according to our data it is the group that protests the most in Chile, making them a substantially important group. Second, workers are a classic actor in Latin American protest (from automotive operators in Sao Paulo to Peruvian of Bolivian miners, including Uruguayan sugar cane workers or the Argentinian unemployed), and here we are interested in providing clues for regional research. Third, workers are clearly positioned in the two axes defined above, which allow establishing a more clear-cut association.

If our reasoning is correct, by virtue of their position in the productive sphere and their capacity to interrupt the productive process, workers should be inclined towards disruptive tactics such as strikes to a greater extent than other groups. With regard to political capital, literature about Chilean unionism establishes that the leadership of the CUT (Central Unitaria de Trabajadores, Workers' United Center, the highest instance for workers' representation in Chile) has been traditionally a space under control of the Concertación (political coalition that unites different center-leftist parties) and Chile's Communist Party (Frías, 2008). This leads them to have an important degree of impact, although not decisive, on the political apparatus. Therefore, according to our reasoning, the workers would be less inclined than other groups to adopt violent tactics, which could risk their considerable political capital.

Something similar could be expected of the (sporadic) protests carried out by business people (in Chile, primarily protests by agricultural landowners) who have the capacity to exert pressure through disruptive tactics. Yet at the same time, this insertion would stop them from adopting violent tactics because they are excessively anti-systemic and risky for their political capital.

However, in the case of employed workers, this relationship is more defined, stemming from the long history of non-violent disruptive tactics of the Chilean unionist movement -one of the oldest and most consolidated of the region. In some way, the adoption of these tactics (strikes, taking of facilities) reinforces the collective identity of workers and allows them to connect to the struggle practices of their ancestors, giving them continuity in time.

If this is the case, we could expect that:

Hypothesis 3: Protest events with the presence of employed workers' groups exhibit disruptive yet non-violent tactics to a greater extent than other groups.

With "other groups" we are referring specifically to those with lower insertion into the productive sphere and with less political capital. In particular to groups of residents, indigenous peoples, informal workers, unemployed and clandestine groups of presumably anarchist inspiration (which in Chile receive the name of encapuchados "hooded people" because they hide their faces). These groups are characterized for having a relatively low insertion into productive spheres, and for having a low political capital (Cubillos, 2012; Llancaqueo, 2007). Nevertheless, it is true that each one of them contains huge internal heterogeneity, and in bulk analysis we could expect that, because they are groups that are highly marginalized from production spheres and power, they will be less reluctant to use violent tactics as a means to attain their objectives than groups of employed workers who would have more to lose. Therefore:

Hypothesis 4: The protest events with presence of groups with low political capital and weak productive insertion have greater probability of exhibiting violent tactics than employed workers.

Finally, both student protests and protests by the various groups we bring together under the "civil society" title (ecologist, community, religious, sexual diversity, human rights defense groups, etc.) are characterized by having a low level of insertion into the productive sphere but an intermediate level of political capital, primarily because they have been gaining greater legitimacy in public opinion and greater capacity to process their demands institutionally (Somma and Medel, 2015; Navia and Pirinoli, 2015). However, the huge internal diversity leads them to mobilize with tactics that range from the conventional to the violent.

We suggest that a way to observe finer relationships between the groups and the use of specific tactics is to include a term of interaction between the groups and the presence, or not, of radical demands in the protest. With the radical nature of demands we refer basically to demands that insist on great institutional reforms to be satisfied, or else, straightforward anti-systemic demands.

We consider that including a term of interaction with the groups is justified for many reasons. First, because since violent tactics have a high cost today in Chile (risk of repression, anti-terrorist law, social stigma), it can be that they appear only in face of the combination of certain types of groups and certain radical demands, which are mutually strengthened. Therefore, it is possible for the presence of radical demands to increase the incentives to adopt transgressive tactics, which represent greater risks and costs for protesters (McAdam, 1986).

Secondly, the most radical demands tend to be connected to feelings of disenfranchisement with regard to others (Gurr, 1968). These privations provide fertile ground for the construction of collective action frameworks (Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford, 1986), giving rise to intense negative emotions such as rage, indignation or humiliation (Jasper, 1998) and to identifying a human agent responsible for such privations. Transgressive tactics -disruptive or occasionally violent- seem to be particularly suitable to channel these emotions despite their higher personal costs.

Finally, the demands themselves also shape an identity and a way of protesting. A peaceful group would be exposed to serious identity dilemmas if it adopts as a tactic the assassination of politicians who promote international wars. Further, the identity of a group can be strongly defined by a demand in particular (Bernstein, 1997), which can lead them to use certain types of tactics that coincide with those demands.

Because of all this, we regard exploring the interaction between the type of demand and the groups mobilized to be fundamental. Although it is not strange for there to be associations between both things, the same group could adopt radical and non-radical demands under different contexts. For example, on certain occasions Mapuche groups demanded the obligatory nature of using native language in schools of certain regions as a way to preserve their ancestral identities (which would not constitute a radical demand), while on other occasions they demanded the autonomy of certain territories from the State (which would be radical, since it requires modifying the territorial reach of the Chilean State).

Presence of organizations

Piven and Cloward (1979) stated that higher levels of internal organization of social movements (in terms of presence of formal rules, regulations and hierarchies) decrease their spontaneity and vitality, increasing the chances of coopting by political authorities and leading to more conventional and institutionalized forms of pressure. Various studies have supported this thesis (Koopmans, 1993; Kriesi et al., 1995). For example, in a study for four European countries, Kriesi et al. (1995) discovered that the involvement of organizations in a cycle or wave of protest weakens the use of disruptive tactics and fosters their institutionalization. In this same sense, Staggenborg (1988) found that the institutionalization of movements organized over abortion rights in the United States made conventional tactics more recurring. On the other hand, she shows how a decentralized and informal organizational structure leads to the use of more innovating and disruptive tactics becoming more common (Staggenborg, 1988). This suggests that:

Hypothesis 5: Protest events with the presence of formal organizations exhibit restrained tactics (conventional or cultural) to a greater extent than protest events without the presence of formal organizations.

Number of participants

The protest's size or ability to convene is a central element when studying the tactical display of the movements. The tactics that activists decide to use within the context of a massive convocation will not have the same effectiveness as when the protest convenes only a handful of people. Likewise, the ability to convene is not something necessarily external or contextual to protesters; the decision to convene a large number of people or to mobilize in small groups could be a strategic calculation as the most efficient path to generate pressure from the groups that protest is evaluated.

The direction that the bulk of the literature has established with regard to the number of participants and the tactics observed is that the larger the size of the protest, the greater the possibility of observing transgressive tactics. For certain authors, increasing the number of participants decreases the risks of repression for their individual members (Oberschall, 1995; Granovetter, 1978; Taylor and Van Dyke, 2004), thus decreasing the obstacles for adopting transgressive tactics. Therefore, a greater number of participants would increase the propensity towards disruptive or violent tactics because of the ability for anonymity that massive convocations provide.

In this same line, but following a more elaborate mechanism, other authors have argued that it is not the size in itself that increases the probability of violence, but rather the interaction between protesters and police repression, which would unleash an escalation of increasingly more transgressive tactics (Della Porta, 1995; Francisco, 1995; Koopmans, 1997). Therefore, the greater number of protesters would be associated to a higher probability of there being police presence and repression (Earl, Soule, and McCarthy, 2003). The mechanism that could be established, thus, is that when the convocation is larger, there is a higher probability of police presence and repression and, therefore, higher probability of seeing transgressive tactics by protesters as a reaction to this repression. Dynamics of this sort could have influenced some massive demonstrations of Brazil's Landless Workers' Movement, Bolivia's "war over water" (1999), Chile's student protests in 2011, or Mexico's 1968 movements. Therefore:

Hypothesis 6: Protest events with a higher number of participants exhibit transgressive tactics (disruptive or violent) to a greater extent than those with a lower number of participants.

Data, variables and methods

To test the hypotheses presented above we resorted to data obtained through the methodology known as "protest event analysis" (PEA). Since the 1970s, the pea has been widely used in diverse countries of the world to study the dynamics of collective protest (Koopmans and Rucht, 2002; Kriesi et al., 1995; Olzak, 1989). This method consists in building and analyzing statistically a database that records the protest events that take place in the space and period of interest. The main source about the events is the news in national newspapers regarding collective protests in public places. The information referred to each event is codified into individual files according to a series of attributes about it and then statistical analysis is performed.

Although there are possible biases in selecting and reporting the events (Koopmans and Rucht, 2002, p. 200; Ortiz et al., 2005; Wilkes and Ricard, 2007), the great advantage of pea is that it allows substituting vague or anecdotal opinions for a precise and detailed knowledge about the protest. Among other themes, this has allowed studying the interactions between movements and counter-movements (Franzosi, 1999); the evolution and characteristics of protest campaigns (Kousis, 1999); and the internal dynamics and characteristics of the movements (Walker, Martin, McCarthy 2008; Van Dyke, Soule and Taylor, 2005). As far as we know, the PEA has not been used in Chile, and its applications in Latin America are few (e.g.,Almeida, 2008, for El Salvador; Inclán, 2008, for Mexico).

Our database contains quantitative information about 2 342 protest events that took place throughout Chile between January 2000 and August 2012. These protests were carried out by an endless number of groups and social movements motivated by quite diverse demands. The information comes from the protest chronologies of the Social Observatory for Latin America (Observatorio Social de América Latina, OSAL) at the Central American Social Sciences Center (Centro Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales, Clacso). Based on several national printed press, radio and Internet media of diverse political ideologies (including activists' websites), OSAL records the protest events that take place every day in Chile. Precisely one of the strengths of the OSAL's records in comparison to most of the pea available for other countries, is the use of a variety of written, radio and web media. This allows triangulating the information and reducing substantially (although never completely) the selection biases (Earl, Martin, McCarthy and Soule, 2004).1

In a brief description of each event -typically a couple of paragraphs- OSAL provides information about many variables of interest for the study of protest, including date and place, estimated number of participants, organizations involved, demands, tactics, targets and police action. The extent of agreement between codifiers was around 90 per cent, which is considered more than acceptable for studies of this type.

Dependent variable. Consistent with our prior conceptualization of the protest tactics, our first dependent variable is a categorical variable with four categories: conventional, cultural, disruptive or violent. As we have seen, the first two are restrained tactics; the latter two are transgressive tactics. For this we re-codified in each one of these four types a total of 37 specific tactics gathered in the study. In addition, in later models we used a second dependent variable that indicates which one is the secondary tactic (if it is recorded). Table 1 presents some examples (complete details available upon request). Given the categorical nature of the dependent variables we will perform a multinomial logistic regression (Long, 1997).

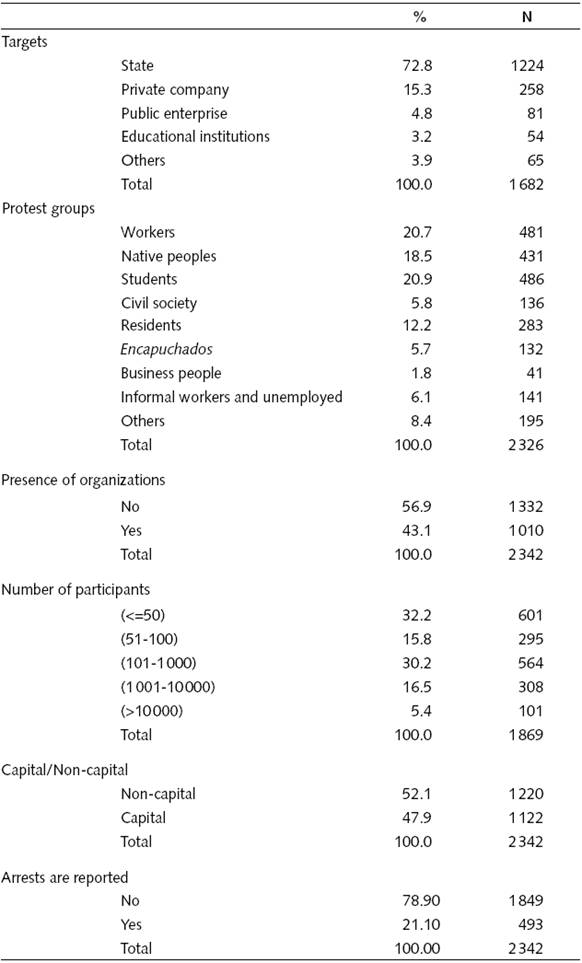

Independent variables. We considered five targets of protest: the State, which includes national, regional or local governments and authorities (72.8%; we did not find significant differences between the different types of authorities, after which we decided to group them in this general category), private companies (national or international, 15.3%), public enterprises (which require a category of their own because, albeit they belong to the State, they operate with a logic of companies, 4.8%), educational institutions (public and private, where the latter are almost inexistent, 3.2%), and "others" scarce and difficult to interpret (3.9%). In order to test hypotheses 1 and 2, the category of reference is the State.

To explore the relationships between the groups involved in protest and the tactics (hypotheses 3 and 4), we considered the following groups (their corresponding percentage is shown in a parenthesis in the event total): employed workers (20.7%), native peoples (including both urban and rural protests, primarily Mapuche, 18.5%), students (20.9%), "civil society" groups (religious, ecologists, feminists, animalists, human rights and others; 5.8%), residents (mainly groups organized around habitational demands, 12.2%), encapuchados2 (5.7%), business people (1.8%), informal workers and unemployed (6.1%) and "others" (which gathers small groups with few mentions that are difficult to interpret theoretically; 8.4%). We included a categorical variable that indicates the presence of each group, except workers that gather the highest number of mentions and operate as category of reference. Thus, the coefficients of the groups indicate the tactical differences between each group and the employed workers, who as discussed above, are the focus of our analysis.

Likewise, and related with the prior hypotheses, we created a variable to measure the presence or absence of radical demands. With radical demands we refer to all the demands that entail revolutionary or anti-systemic demands (anti-globalization, anti-transnational companies, anti-neoliberalism, anarchists, okupas and/or libertarians) or else demands that entail great institutional reforms to be satisfied (reform in political rules, constituent assembly, free education, end to the companies' profit, end to pension systems, returning Mapuche territories, condoning habitational debts) where the value 1 indicates the presence of radical demands (36.4%) and the value 0 their absence or, otherwise, the presence of non-radical demands (63.6%).

The variable that measures the presence of organizations (hypothesis 5) has a value 1 if the presence of some formal organization (for example student, labor, indigenous, etc.; 43.1%) is mentioned in the description of the protest, and 0 if it is not (56.9%).

Finally, the number of participants estimated (hypothesis 6) tends to be reported in the description of events. When the number of participants differs between what is reported by event organizers and the police, the codifier was requested to calculate an average. According to our theoretical discussion, when increasing the number of participants there would be greater chance of observing transgressive tactics, whether because the risks of repression for its individual members decrease, decreasing the obstacles to adopt transgressive tactics; or else because it is the same direct repression in massive events that provokes an escalation of transgressive tactics. However, the cutting point is not clear, that is, from what point there begins to be more propensity towards transgressive tactics. Since these complexities open the possibility to non-linear relationships, we used five categories to indicate the estimated size of the protest: 1=less than 50 participants (32.2%); 2=51 to 100 participants (15.8%); 3=101 to 1 000 (30.2%); 4=1 001 to 10 000 (16.5%); and 5=10 000 and more (5.4%). The first category works as a reference.

Control variables. To evaluate the "net" impact of these factors of protest tactics, we controlled for three variables that previous studies suggest as relevant. The first indicates whether the protest takes place or not in the country's capital, with a value of 1 for protests in Santiago (47.9%) and 0 otherwise (52.1%). In a highly centralized country like Chile, the greater visibility of protests in the capital could increase, for activists, the risks and costs of using transgressive tactics (disruptive or violent), which should consequently motivate them to use restrained tactics (conventional or cultural; Van Dyke, Soule and Taylor, 2005; Taylor and Van Dyke, 2004).

In the second place, we included the variable of year as a continuous variable. Considering that our data cover twelve years, this variable allows controlling whether the presence of certain tactics are affected by the passage of time. For example, it could happen that the number of cultural or violent tactics have become more preeminent in recent years and had been less relevant at the beginning of the 2000s when the forms of protest could have been more restricted to conventional and disruptive tactics.

Finally, we included a dichotomous variable that indicates whether during the protest there were arrests (1, 21.1%) or not (0, 78.9%). Arrests are a good reflection of police presence and repression, and repression can induce violent behavior during the protest (Davenport, 2007). Obviously, it is also plausible that transgressive tactics produce police actions, so we are not attempting to make causal statements but rather simply to control for possible alternative factors.

In addition, two other variables were included regarding political context, specifically: presence of presidential campaign (four months before the election), presence of honeymoon (four first months of each government). Since neither of the coefficients was significant and the results remained substantially identical, it was decided not to include those variables in the final analysis.

Table 2 presents the frequencies and percentages of the independent variables used in the study.

Results

Table 3 describes our dependent variable. For this purpose, we considered the principal tactic and the secondary tactic reported. In 2 294 events, information was recorded for at least one tactic, and in 877 of them a second tactic was recorded (the third and subsequent records of tactics were very scarce). In the principal tactic, conventional ones are the most frequent (44.9%), followed by disruptive (33.7%), violent (17.3%), and finally cultural (4%). In terms of the secondary tactic, the most frequent are the violent ones (31.7%), followed by conventional (29.5%), disruptive (26.3%) and cultural (12.4%). This shows firstly the importance of tactical diversity in protests in Chile, and gives empirical relevance to the question about their determinants. Secondly, it shows the difference between the first tactic used in protest and the second one, where in the latter it is clear that the categories that seemed more marginal in the first tactic (violent, cultural) take on greater importance.

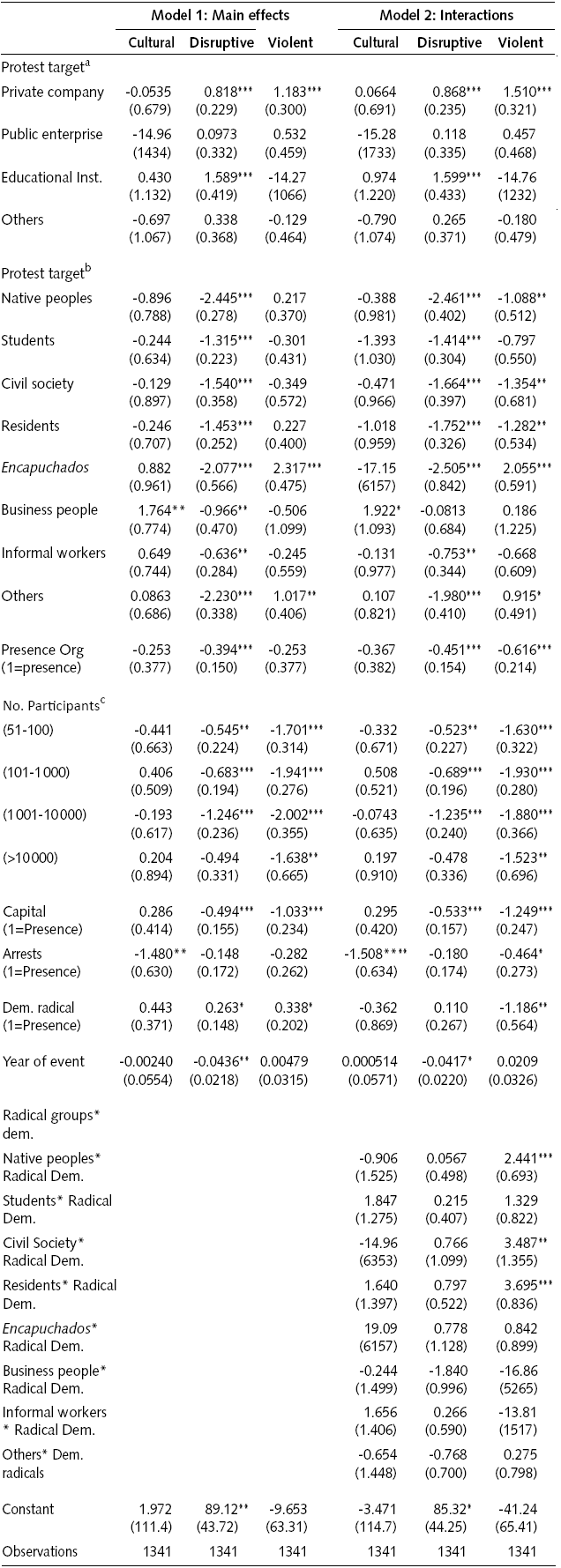

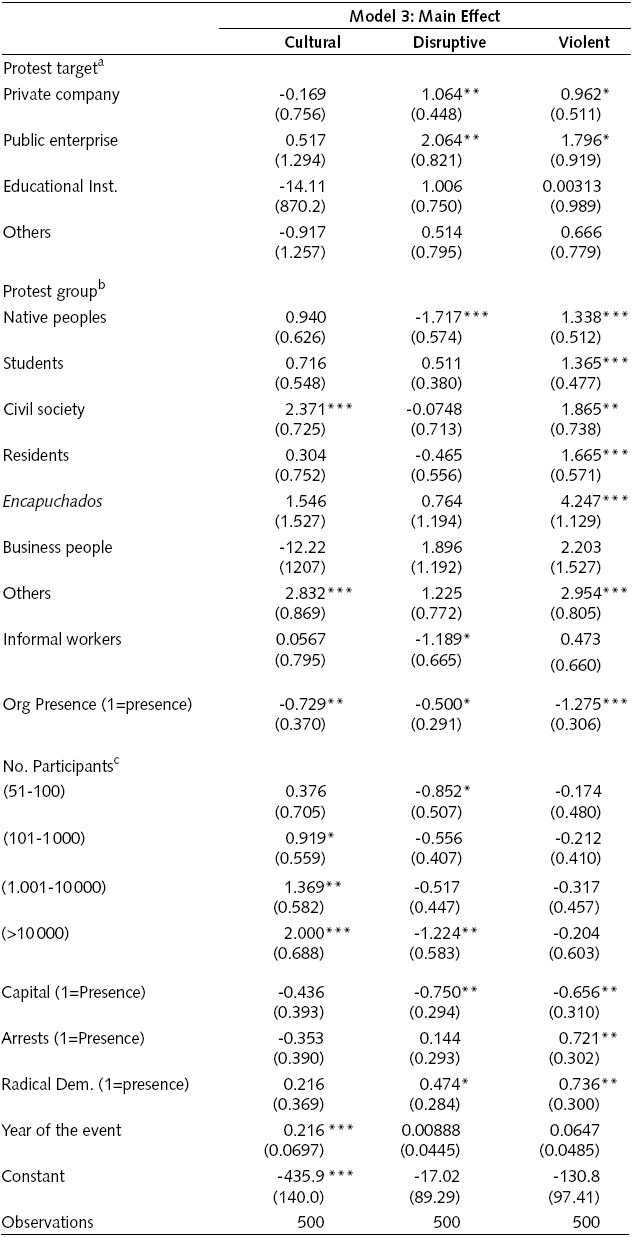

To study the relationships between the dependent and independent variables, it is necessary to consider the multivariate regression models to obtain firm evidence about our hypotheses. For this purpose, Table 4 presents two multinomial logistic regression models, one with the principal effects and the second with interaction variables between groups and types of demands. In turn, Table 5 presents the multinomial logistic regression models with principal effects for the secondary tactic. Likewise, an interaction model was tested for the secondary tactic, which was not significant. Therefore, and due to the lower number of cases, we prefer not to ask more of the model, so only the principal effects are reported for the case of the secondary tactic.

Table 4 Multinomial logistic regression principal tactic of the protest (category or reference: conventional tactic)

Source: Analysis of protest events (Fondecyt Proyect 11121147). Standard errors inside parenthesis ***p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.1. Log likelihood = (Model 1: -1169.8835; Model 2: -1140.8227). Pseudo R2 = (Model 1: 0.2185; Model 2: 0.2379). aState category of reference . bCategory of reference is workers. cCategory of reference ≤ 50.

Table 5 Multinomial logistic regression of the protest secondary tactic (category or reference: conventional tactic)

Source: Analysis of protest events (Fondecyt Proyect 11121147). Standard errors in parenthesis. *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.1. Log likelihood = (Model 1: -541.5074). Pseudo R2 = (Model 1: 0.1896). aCategory of reference is the State. bCategory of reference is workers. . cCategory of reference ≤ 50.

In the case of the multinomial regression, it is necessary to operate with a reference category of the dependent variable, so that the category of conventional tactic has been used as reference, after which each tactic will be examined around that category and not the others. The models included simultaneously the seven independent variables that we worked with, four central independent variables (targets, groups, organizational presence and number of participants), and the three control variables (capital/region, arrests and year). Regretfully, the high levels of missing cases in some variables (such as the number of participants or target) distinctly reduce the number of observations to N=1 341 in the first model (principal tactic) and to N=500 (secondary tactic) in the second. Next, we review the results for each one of our hypotheses.

In general the models provide evidence that is consistent with hypotheses 1 and 2. Both the principal and the secondary tactics (Table 4 and table 5) show that the events with state targets exhibit conventional tactics to a greater extent than events with non-state targets (especially private companies where differences are highly significant in both models). In the principal tactic, we see that in reference to the state target, no target is significant in terms of the chances3 of carrying out cultural tactics. With regard to disruptive tactics, there are two targets that are significant: private companies and educational institutions have 2.3 and 4.8 more chances of carrying out disruptive tactics in relation to the State, compared to conventional tactics, which confirms hypothesis 2 about transgressive tactics being directed primarily to non-state targets. Finally, in terms of violent tactics, we see that the private company target is the only significant one, and that it had 3.3 more chances of receiving violent tactics than the State, compared to conventional tactics. It is interesting that educational institutions are attacked with disruptive tactics, but not with violent tactics -it is more likely that these institutions be occupied than destroyed.

For the secondary tactics, the trend remains in terms of the target of private companies, although the difference with disruptive tactics is intensified (2.8 more chances) and decreases slightly for violent tactics (2.6 more chances). On the other hand, educational institutions lose significance while public enterprises gain, increasing the chances of receiving transgressive tactics -7.8 for disruptive tactics and 6.1 for violent tactics- compared to the State, in reference to conventional tactics.

In sum, protests are carried out against the State through restrained tactics, against private companies through disruptive and violent tactics, and against educational institutions through disruptive tactics (although not violent).

Regarding hypotheses 3 and 4, considerably different tactics can be seen in function of what group is protesting (here we emphasize the contrast between workers -the category of reference- and the rest). In general our intuition is consistent with the evidence. Let us see first the principal tactic. We observe that the presence of employed workers is associated to disruptive tactics to a much greater extent than to all the other groups, even more than business people (almost all the differences are statistically significant). For example, the presence of students reduces the chances of disruptive tactics almost threefold (in comparison to events with the presence of workers), and the difference is much more marked in the contrast with native peoples and "civil society". Although the current Labor Law in Chile (that dates from dictatorial times) allows striking -an important disruptive tactic- only in some companies have workers been able to organize into several sectors to overcome these barriers. Also, the incentives for disruptive labor protest are possibly accentuated given the productive fragmentation and new types of jobs (Echeverría, 2010). These results sustain the argument that the new cycle of protest in workers' movement, led by outsourced workers, has still been marked by disruptive tactics, primarily by illegal strikes (Echeverría, 2010; Núñez, 2009).

Regarding the models with terms of interaction, we can see that indeed the effect of certain groups is different depending on whether or not there is presence of radical demands. Without interactions, the encapuchados and the "others" (undefined groups) are the only groups more likely than employed workers to adopt violent tactics; but when groups and demands interact, several groups (native peoples, civil society and residents) are less susceptible to adopting violent tactics than workers if they have non-radical demands, but more violent than workers if they have radical demands.

This partially confirms hypothesis 4 in that, indeed, groups with less political capital and less insertion into the productive sphere (residents, native peoples) would be less prone than employed workers to carry out violent tactics, but we see that this only happens in the presence of radical demands. This suggests how complex it is to study these groups given the internal pluralism and the tactical variety that they operate with according to the context.

In terms of the secondary tactic, a higher propensity of civil society for cultural tactics is observed. This indicates that cultural tactics would be operating as a complementary tactic rather than a principal one (for example, a performance in a demonstration).

In sum, tactical specialization is observed in employed workers: compared to other groups, they would resort more to disruption but would leave aside violent tactics, in reference to conventional tactics. This partially corroborates hypothesis 3, since business people in their turn do not move as close to the workers, but rather towards restrained tactics. Regarding hypothesis 4, we see that residents and native peoples effectively lean more towards transgressive tactics, but only in the presence of radical demands. In turn, informal workers do not show very clear trends, as opposed to the encapuchados who are specialized in violent tactics even in the absence of radical demands (group that is defined basically in function of violent actions). Finally, we can see that for the case of students very clear trends cannot be assumed, which shows among other things the tactical diversity of the group. Civil society sheds more light about its tactical diversity, insofar as we saw that it carries out violent tactics in the presence of radical demands as a principal tactic, but is inclined towards cultural ones as a secondary tactic.

On the other hand, the evidence is also partially consistent with hypothesis 5, related to the presence of formal organizations in the protest event. When organizations are reported in the protest, the chances of observing transgressive tactics (disruptive and violent) decrease significantly, compared to conventional ones both in the principal tactic and in the secondary tactic. In addition it is interesting that the chances of observing cultural tactics also decrease significantly with the presence of organizations, and in the case of the secondary tactic this decrease is significant, suggesting that cultural protest is not usually carried out by formal organizations within a protest. In sum, the coordination and structuring roles of collective action by organizations would seem to smooth out the most transgressive aspects of protest and direct them towards conventional tactics, but not cultural ones.

Finally, we observe that both models are inconsistent with hypothesis 6, relative to the number of participants in the event. We see that, in contrast to what the literature suggests, an increase in the number of participants decreases the chances of observing transgressive tactics with regard to conventional ones. These differences are statistically significant for almost all levels in the case of the principal tactic, while for the secondary tactic, although the relationship is the same, it is only significant for events with less than 100 and more than 10 thousand attendees. Likewise, the chances of observing cultural tactics increases in the secondary tactic, and progressively, as the number of participants grows, reaching up to 7.4 more chances of taking place in the cases of massive events (more than 10 thousand attendees) compared to small groups. It is intriguing and counter-intuitive that transgressive tactics are carried out in small groups and not in massive events in Chile. We will delve into this point in the conclusions.

We will mention briefly what happens with the control variables. As expected, when the protest takes place in the capital conventional tactics prevail significantly more, and disruptive and violent ones less, than when it develops in other regions. With regard to the year variable, we see that as time passes the chances of using disruptive tactics compared to conventional ones as principal tactic decrease, and the chances of carrying out cultural tactics compared to conventional ones as secondary tactic increase. In turn, arrests, as proxy for police presence and repression, do not increase the chances of observing more transgressive tactics in the principal tactic compared to the conventional one, something that does happen with the secondary tactic, particularly in violent tactics whose increase is significant.

Conclusions

This article attempted to respond the question of why collective protest tactics vary between different events. The theme is relevant for a global comprehension of social movements. Tactics impact the ability of movements to achieve their objectives, and their image and legitimacy before the authorities and public opinion. All of this has implications for the movements' ability to change and their own development and survival. Even so, the issue of social movements is still quite unexplored in the Chilean literature and in Latin America in general, at least with analysis data of protest events like we are doing here. In operational terms, we distinguish between restrained (conventional or cultural) and transgressive (disruptive or violent) tactics, and we use a database of protest events that took place in Chile between 2000 and 2012. This allows us to explore systematically the diversity of tactics, as well as the impact that different variables have on them, which we identify based on the literature in the subject.

The analysis presents several results that we find interesting. First, although conventional tactics are the most frequent, Chilean protest is diverse. In addition to demonstrations and conventional concentrations, protest is also expressed quite frequently through disruptive means (such as taking of premises, activity strikes and roadblocks), through violent means (including destroying property, looting and setting fires), and occasionally through artistic and cultural manifestations.

Second, several characteristics of the protest events seem to influence the different tactics adopted. For example, with regard to the protest targets, when the target is the State the use of restrained tactics is prioritized, while when the target is a private company (national or international) or an educational institution, transgressive tactics are prioritized. This is consistent with the argument that it is more difficult to challenge the State through violence since it concentrates the coercive resources; something that does not occur with other entities.

We also find interesting differences between the different groups that participate in the protests. Conceptually, we hypothesize that the tactics vary according to the level of political capital and the relationship between the groups and the productive sphere. Specifically, we find that, in comparison to other groups, workers prefer disruptive tactics but avoid violent and conventional tactics. Also, "civil society" groups opt more for cultural tactics as secondary tactic. It was useful also to have been able to control for groups of encapuchados, which are defined primarily by the use of violent tactics, since we were able to isolate their effect on violent tactics in the other variables of interest. Finally, we see that the groups with less political capital and less inserted into the productive sphere (primarily encapuchados, residents and native peoples) would opt more for violent tactics, but only in the presence of radical demands, which speaks of the internal diversity of the movement and of the importance of the term of interaction included.

Additionally, when there is the presence of formal organizations in protest it is quite less likely to observe disruptive and violent tactics. When observing the secondary tactic, we could see that it was also less likely to observe cultural tactics. This is consistent with the thesis that more organized and structured movements use tactics that are more acceptable to the statu quo than the more spontaneous movements.

The only hypothesis that was not proven was with regard to the number of participants in the event, where exactly the opposite occurs from what is described by the literature (mainly from industrialized countries). In contrast with what was expected, the higher the number of participants, the lower the chances of observing transgressive tactics with regard to conventional ones.

It is interesting that in Chile the relationship between the size of the protest and the tactics does not follow the same pattern than in industrialized countries. In Chile, transgressive protests are carried out primarily by small groups. Following Koopmans (1993), we understand that social movements are aware of the adoption of their strategies, and not simple victims of the counter-strategies of the authorities. From this that the reaction of movements in face of repression can take different routes, with the radicalization of protests being only one of them. Indeed, one of the consequences of the season of student mobilization in 2006 in Chile was a huge change of strategy by students. When they say that their days of peaceful mobilization were being harshly repressed due to loutish actions by small groups, the principal tactic of students turned towards occupying their premises. This surprised the authorities because of the chain reaction that it caused and because of the level of organization of the tactic used by the movement (Mardones, 2007).

On the other hand, in Chile there are disruptive tactics -such as barricades in villages, banging on pots and pans (cacerolazos), or bonfires- that are part of a heritage from the struggle against the dictatorship in the 1980s (Valenzuela, 1984; Espinoza, 1988; Campero, 1987). Through these tactics, there is an attempt to avoid direct repression by the police, acting in small and organized groups. Since the end of the 1990s, there has also been an increase in ethnic protests for territorial recognition (Foerster, 1999; Lavenchy, 2003; Tricot, 2009) which entail disruption, mostly with roadblocks, fire attacks, and other disruptive elements that tend to be carried out by small groups that seek to avoid direct contact with the police.

It is possible that this tentative pattern towards disruption by small groups is not originally from Chile, but rather also from other Latin American contexts that have undergone strong patterns of state repression throughout their history (Auyero, 2002).

All of these findings suggest future research lines regarding the protest tactics in Chile and Latin America. First, it would be worthwhile to perform studies that allow delving into the situation of specific social movements to achieve a more refined understanding of their tactical repertoire and to explore their cultural and historical origin. Second, it would be interesting to study how the interaction between social movements, the State and civil society define the use of certain types of tactics throughout time (McAdam, 1983, for an early example). Therefore, the diversity of protest targets that we find allow providing an empirical foundation to Latin American theories about the constitution of new social actors and a new more complex institutional and societal scenario (Garretón, 2002; Gómez Leyton, 2010). This also opens up new possibilities. For example, a comparative study could be performed about how different levels of advancement of Neoliberalism devolve greater weight and public responsibility to non-state institutions, exposing them increasingly more to become targets of collective protest.

Finally, the limitations of this article should be pointed out, which also open up more possibilities for research. Firstly, although the pea allowed advancing the knowledge of protest dynamics substantially, the literature has not ceased to insist on the possible biases of coverage, information and approach to the events in mass media. Not all protest events have the same odds of being covered by media (and therefore incorporated into the database), not all information relevant to the researcher appears for all events covered, and there are certainly biases in the "framing" that different media give to protests, which can affect the information gathered (Wilkes and Ricard, 2007). Although our database considers various media of different ideological affiliation, and although we gathered hundreds of events for a relatively small countries like Chile, future studies with more resources than ours should incorporate more sources to the survey.

Secondly, although following the literature we have assumed that certain characteristics of the events (such as the protest group or the protest target) impact the tactics, the contrary can naturally happen. For example, groups used to adopting certain tactics can feel more comfortable facing certain targets or raising certain demands. There is still no satisfactory response in the literature to this problem, where it is probable that a mixed study that combines quantitative and qualitative techniques can be a good path to this knowledge. Another possible future line consists in studying the impact of the aggregate characteristics of protest during a previous period (t-1 ) on the tactics in the present (t0 ).

Finally, although here we performed a transversal analysis studying the role of variables linked to the very protest event, future studies could be carried out longitudinally to consider factors of the broader social, political and economic context. For example, there is solid evidence that certain tactics disseminate throughout time or space (Myers, 2000). It could happen that contextual factors impact the more immediate factors that we considered here, or else that the first reduce the importance of the latter. We hope this study serves as inspiration for others to continue to develop these types of studies in the future.

REFERENCES

Almeida, P.D. (2008), Waves of Protest: Popular Struggle in El Salvador, 1925-2005 vol. 29, Minnesota, Universidad de Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Auyero, J. (2002), "Los cambios en el repertorio de la protesta social en la Argentina", Desarrollo Económico 42(66), pp. 187-210. [ Links ]

Bernstein, M. (1997), "Celebration and Suppression: Strategic Uses of Identity by the Lesbian and Gay Movement", American Journal of Sociology 103, pp. 531-65. [ Links ]

Benford, R.D. (1993), "Frame Disputes within the Nuclear Disarmament Movement", Social Forces 71(3), pp. 677-701. [ Links ]

Benford, R.D. y D.A. Snow (2000), "Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment", Annual Review of Sociology 26, pp. 611-639. [ Links ]

Campero, G. (1987), Entre la sobrevivencia y la acción política: Las organizaciones de pobladores en Santiago Santiago, Estudios ILET. [ Links ]

Cohen, J.L. (1985), "Strategy or Identity: New Theoretical Paradigms and Contemporary Social Movements", Social Research 52, pp. 663-716. [ Links ]

Crozat, M. (1998), "Are the Times a-Changin? Assessing the Acceptance of Protest in Western Democracies", The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for the New Century pp. 59-82. [ Links ]

Cubillos C. (2012), "Los socialistas en el poder y la securitización de la política: El Estado frente a la protesta social mapuche y estudiantil en el Chile del siglo XXI", tesis, Flacso Sede Ecuador, Quito. [ Links ]

Davenport, C. (2007), "State Repression and Political Order", Annual Review of Political Science 10, pp. 1-23. [ Links ]

Della Porta, D. (1995), Social Movements, Political Violence, and The State: A Comparative Analysis of Italy and Germany Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Della Porta, D. y M. Diani (2006) Social Movements: An Introduction Oxford, Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Donoso, S. (2013), "Dynamics of Change in Chile: Explaining the Emergence of the 2006 Pingüino Movement", Journal of Latin American Studies 45(01), pp. 1-29. [ Links ]

Earl, J., S.A. Soule y J.D. McCarthy (2003), "Protest Under Fire? Explaining the Policing of Protest", American Sociological Review 68(4), pp. 581-606. [ Links ]

Earl, J., A. Martin, J.D. McCarthy y S.A. Soule (2004), "The Use of Newspaper Data in the Study of Collective Action", Annual Review of Sociology 30(1), pp. 65-80. [ Links ]

Espinoza, V. (1988), Para una historia de los pobres de la ciudad Santiago, Ediciones Sur. [ Links ]

Echeverría, M. (2010), La historia inconclusa de la subcontratación y el relato de los trabajadores Santiago Gobierno de Chile, Dirección del Trabajo. [ Links ]

Foerster, R. (1999), "¿Movimiento étnico o movimiento etnonacional mapuche", Revista de Crítica Cultural 18, pp. 52-58. [ Links ]

Francisco, R.A. (1995), The Relationship between Coercion and Protest. An Empirical Evaluation in Three Coercive States", Journal of Conflict Resolution 39(2) pp. 263-282. [ Links ]

Franzosi, R. (1999), "The Return of the Actor: Interaction Networks among Social Actors during Periods of High Mobilization (Italy, 1919-1922)", Mobilization, Special Issue: Protest Event Analysis 4(2), pp. 131-49. [ Links ]

Frías, P. (2008), Los desafíos del sindicalismo en los inicios del siglo XXI Buenos Aires, Clacso. [ Links ]

Garretón, M.A. (2002), "La transformación de la acción colectiva en América Latina", Revista de la CEPAL 76, pp. 7-24. [ Links ]

Giugni, M.G. (1998), "Was it Worth the Effort? The Outcomes and Consequences of Social Movements", Annual Review of Sociology 24, pp. 371-393. [ Links ]

Gómez Leyton, J.C. (2010), Política, democracia y ciudadanía en una sociedad neoliberal (Chile: 1990-2010) Santiago, Clacso/Editorial Universidad Arcis. [ Links ]

Granovetter, M. (1978), "Threshold Models of Collective Behavior", American Journal of Sociology 83(6), pp. 1420-1443. [ Links ]

Goldstone, J.A. (ed.) (2003), States, Parties, and Social Movements Nueva York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gurr, Ted Robert (1968), "A Causal Model of Civil Strife: A Comparative Analysis Using New Indices", American Political Science Review 62, pp. pp. 1104-1124. [ Links ]

Inclán, M. de la L. (2008), "From the ¡Ya Basta! to the Caracoles: Zapatista Mobilization under Transitional Conditions", American Journal of Sociology 113(5), pp. 1316-1350. [ Links ]

Jasper, J.M. (1998), "The Emotions of Protest: Affective and Reactive Emotions in and Around Social Movements", Sociological Forum 13, pp. 397-424. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J.C. (1983), "Resource Mobilization Theory and the Study of Social Movements", Annual Review of Sociology 9, pp. 527-553. [ Links ]

Kimport, K., N. Van Dyke y E.A. Andersen (2009), "Culture and Mobilization: Tactical Repertoires, Same-Sex Weddings, and the Impact on Gay Activism", American Sociological Review 74(6), 865-890. [ Links ]

King, B.G. y Pearce, N.A. (2010), "The Contentiousness of Markets: Politics, Social Movements, and Institutional Change in Markets", Annual Review of Sociology 36 pp. 249-267. [ Links ]

Koopmans, R. (1993), "The Dynamics of Protest Waves: West Germany, 1965 to 1989", American Sociological Review 58(5), pp. 637-658. [ Links ]

Koopmans, R. (1997), "Dynamics of Repression and Mobilization: The German Extreme Right in the 1990s", Mobilization an International Journal 2(2) pp. 149-164. [ Links ]

Koopmans, R. y D. Rucht (2002), Protest Event AnalysisMethods of Social Movement Research 16 pp. 231-259. [ Links ]

Kornhauser, W. (1969), The Politics of Mass Society Glencoe, Free Press (trad.) Los nuevos movimientos sociales. De la ideología a la identidad, Madrid, CIS. [ Links ]

Kousis, M. (1999), "Environmental Protest Cases: The City, the Countryside, and the Grassroots in Southern Europe", Mobilization, Special Issue: Protest Event Analysis 4(2), pp. 223-238. [ Links ]

Kriesi, H., R. Koopmans, J.W. Duyvendak y M.G. Giugni (1995), New Social Movements in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Lavenchy, J. (2003), El pueblo mapuche y la globalización. Apuntes para una propuesta de comprensión de la cuestión mapuche en una era global Santiago de Chile, Universidad de Chile-FFH. [ Links ]

Llancaqueo, V.T. (2007), "Cronología de los principales hechos en relación a la represión de la protesta social mapuche. Chile 2000-2007", Revista del Observatorio Social de América Latina 22, pp. 277- 293. [ Links ]

Long, J.S. (1997), "Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables", Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences, 7 [ Links ]

Manheim, J.B. (2001), The Death of a Thousand Cuts: Corporate Campaigns and the Attack on the Corporation Londres, Routledge. [ Links ]

Mardones Z., R. (2007), "Chile: todas íbamos a ser reinas", Revista de Ciencia Política 27, pp. 79-96. [ Links ]

McAdam, D. (1982), Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970 Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

______ (1983), "Tactical Innovation and the Pace of Insurgency", American Sociological Review, 48, pp. 735-754. [ Links ]

______ (1986), "Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer", American Journal of Sociology, pp. 64-90. [ Links ]

McAdam, D., S. Tarrow y C. Tilly (2001), Dynamics of Contention Nueva York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

McCarthy, J. y M. Zald (1977), "Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory", American Journal of Sociology 82(6), pp. 1212-1241. [ Links ]

Morris, A. (1981), "Black Southern Student Sit-in Movement: An Analysis of Internal Organization", American Sociological Review 46(6), pp.744-67. [ Links ]

______ (1993), "Birmingham Confrontation Reconsidered: An Analysis of the Dynamics and Tactics of Mobilization", American Sociological Review, 58, pp. 621-636. [ Links ]

Myers, D.J. (2000), "The Diffusion of Collective Violence: Infectiousness, Susceptibility, and Mass Media Networks", American Journal of Sociology 106(1), pp. 173-208. [ Links ]

Navia, P. y S. Pirinoli (2015), "The Effect of the Student Protests on the Evolution of Educational Reform Legislation in Chile, 1990-2012", Ponencia presentada en el XXXIV International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA), San Juan, mayo. [ Links ]

Núñez, D. (2009), "El movimiento de trabajadores contratistas de Codelco: Una experiencia innovadora de negociación colectiva", en A.A. Núñez, El renacer de la huelga obrera en Chile. Movimiento sindical en la primera década del siglo XXI Santiago, ICAL. [ Links ]

Oberschall, A. (1995), Social Movements: Ideologies, Interests, and IdentitiesPiscataway Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Offe, C. (1985), "The New Social Movements: Challenging the Boundaries of Institutional Politics", Social Research 52, pp. 817-68. [ Links ]

Olzak, S. (1989), "Analysis of Events in the Study of Collective Action", Annual Review of Sociology 15, pp. 119-141. [ Links ]

Ortiz, D.G., D.J. Myers, E.N. Walls y M.E.D. Díaz (2005), "Where Do We Stand With Newspaper Data?", Mobilization: An International Quarterly10(3), pp. 397-419. [ Links ]

Park, R.E. y E.W. Burgess (1921), Introduction to the Science of Sociology Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Pellow, D.N. (2001), "Environmental Justice and the Political Process: Movements, Corporations, and the State", The Sociological Quarterly 42(1), pp. 47-67. [ Links ]

Piven, F.F. y R.A. Cloward (1979), Poor People's Movements: Why they Succeed, How they Fail Nueva York, Vintage. [ Links ]

Polletta, F. y J.M. Jasper (2001), "Collective Identity and Social Movements", Annual Review of Sociology 27, pp. 283-305. [ Links ]

Schwartz, M. (1988). Radical Protest And Social Structure: The Southern Farmers' Alliance And Cotton Tenancy, 1880-1890 Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Silva, E. (2009), Challenging Neoliberalism in Latin America Nueva York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Somma, N.M. (2015), "Participación ciudadana y activismo digital en América Latina", en B. Sorj y S. Fausto (org.), Internet y movilizaciones sociales: Transformaciones del espacio público y de la sociedad civil Sao Paulo, Ediciones Plataforma Democrática, pp. 103-146. [ Links ]

Somma, N.M. y R.M. Medel (2015), "Shifting Relationships Between Social Movements and Institutional Politics", en Marisa von Bulow y Sofía Donoso (editoras), Post-transition Social Movements in Chile: Organization, Trajectories, and Consequences Palgrave (en prensa). [ Links ]

Smelser, N. (1962), Theory of Collective Behavior Nueva York, Free Press. [ Links ]

Snow, D. A., Jr, E.B. Rochford, S.K. Worden y R.D. Benford (1986), "Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation", American Sociological Review pp. 464-481. [ Links ]

Staggenborg, S. (1988), "Consequences of Professionalization and Formalization in the Pro-Choice Movement", American Sociological Review 53, pp. 585-606. [ Links ]

Tarrow, S. (1998) Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action, and Politics Nueva York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Taylor, V. y N. Van Dyke (2004), "Get up, Stand up': Tactical Repertoires Of Social Movements", The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements pp. 262-293. [ Links ]

Tilly, C. (1978), From Mobilization to Revolution Nueva York, McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

______ (1995) "Contentious Repertoires in Great Britain, 1758-1834", en M. Traugott (ed.), Repertoires and Cycles of Collective Action, Durham, Duke University Press, pp. 15-42. [ Links ]

Tricot, T. (2009), "Lumako: punto de inflexión en el desarrollo del nuevo movimiento mapuche", Historia Actual Online 19, pp. 77-96. [ Links ]

Touraine, A. (1981), The Voice and the Eye: An Analysis of Social Movements Nueva York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Turner, R. y L. Killian (1957), Collective Behavior Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Van Dyke, N., S. Soule y J. McCarthy (2001), "The Role of Organization and Constituency in the Use of Confrontational Tactics by Social Movements", ponencia presentada en Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Anaheim. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, E. (1984), La rebelión de los jóvenes Santiago, Ediciones Sur. [ Links ]

Van Dyke, N., S.A. Soule y V.A. Taylor (2005), "The Targets of Social Movements: Beyond a Focus on the State", Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change 25, pp. 27-51. [ Links ]

Walker, E.T., A.W. Martin y J.D. McCarthy (2008), "Confronting the State, the Corporation, and the Academy: The Influence of Institutional Targets on Social Movement Repertoires", American Journal of Sociology 114(1), pp. 35-76 [ Links ]

Wilkes, R. y D. Ricard (2007), "How does Newspaper Coverage of Collective Action Vary?: Protest by Indigenous People In Canada, The Social Science Journal 44(2), 231-251. [ Links ]

Weber, M. (1964), Economía y sociedad: Esbozo de sociología comprensiva México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

*English translation by Valeria Gama. We thank Conicyt (Chile) for the funding through COES (Center for the Studies of Conflict and Social Cohesion/Centro de Estudios de Conflicto y Cohesión Social, Conicyt/Fondap/15130009) and the Fondecyt project Iniciación en Investigación 11121147 ("La difusión de la protesta colectiva en Chile (2000-2011)".

1The written newspapers reviewed are: El Mercurio, La Nación and La Tercera. The secondary newspapers: Azkintuwe, El Ciudadano, El Siglo y Punto Final. Webpages: El Clarín, Diario El Mercurio, Mapuexpress, Radio Cooperativa.

2The word encapuchados ("hooded people") is a Chilean expression to refer to violent groups that hide their face during the protests. They are small groups (of presumably anarchist orientation) that generally act by destroying public and private property and crashing with the police directly.

Received: January 15, 2015; Accepted: July 14, 2015

texto en

texto en