Introduction

Infectious diseases have a special nature of paramount importance in the medical field: they are usually community problems, and their proper management requires actions directed at social processes. These actions usually impact the well-being of individuals and their social groups. In this context, is there really a direct relationship between ethics and infectious diseases? There should be no doubt about this relationship after living through 2 years of the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic. In this case, we have experienced isolation and social interventionism, together with the ethical dilemmas that arise, for example, in the allocation of scarce medical resources for the treatment of patients who have been infected by the disease, the most important bioethical guiding principle of public health has prevailed: “save the most lives”1.

Importance of ethics in the study of infectious diseases

As the medical services were overwhelmed during the COVID-19 pandemic, the ethical dilemmas surrounding an infectious disease increased (impacting not only medically, but also sociopolitically), the community began to voice its opinions, and healthcare professionals had to decide between those who should receive life-saving treatment and those who should not. Furthermore, the deliberation took place under the scrutiny of a critical and censorious society. In the same context, it was necessary to confront the stigmatization and criminalization of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community and people of African descent, who were unfairly associated with cases of monkeypox or Ebola. This behavior fostered cycles of fear and distanced these communities from health services, hampering efforts to identify cases and encouraging ineffective and highly punitive measures.

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, ethical guidelines were issued in Mexico and other countries to facilitate medical decision-making regarding the allocation of scarce medical resources during periods of peak demand (such resources could be life-saving, particularly invasive mechanical ventilators and hemodialysis machines). The ethical guidelines considered, for example, the use of age as a determining factor in decision-making, which some considered as an excuse for unthinkingly slipping into discrimination, while others argued that age was a valid criterion2.

Despite the warning given by the influenza pandemic a decade ago, the guidelines were exposed to a society that was medically illiterate and even lacking in moral values (where the only thing of value is materialism, money, fame, and fortune). Therefore, in the absence of a genuine altruistic commitment of society, as was to be expected, the criticism was massive and even cruel.

To date, there is no unanimity or social consensus on what would be ideal from a moral point of view, so the debate must remain on the table for decision-makers. After all, the State is a source of guidance and social protection. Hence, the ethics of surveillance require constant evaluation and revision in light of experience (commitment to public health must remain with society to avoid conflict if this situation arises again)3.

In a pluralistic society, people are likely to disagree about what principles should guide the allocation of scarce resources during an adverse event such as a pandemic, whether a group of people should be isolated to prevent contagion, or even whether it is right to participate in a community trial without obtaining prior informed consent on an individual basis; therefore, careful attention to procedures is critical. Consequently, several aspects of procedural justice should be considered, such as public commitment, transparency in decision-making, reliance on grounds and principles that everyone can accept as relevant, oversight by a legitimate institution, and procedures for appealing and reviewing individual decisions in light of challenges to them4.

However, health is a basic human right and essential for social and economic development, as stated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the Jakarta Declaration: “Health promotion is done by and with people, neither imposed nor delivered. It builds the capacity of individuals, groups, organizations, and communities to influence the determinants of health”5. Therefore, the contribution of ethics to public health focuses on designing and implementing policies to monitor and improve the health of populations. However, it goes beyond health care by considering the determinants that promote or hinder the development of healthy societies.

It is not surprising that public health surveillance is the foundation for a timely response to epidemics and communicable disease outbreaks, although it is not limited to infectious diseases. When conducted ethically, surveillance is the foundation of any program that seeks to promote wellness at the population level.

This is the case with programs that contribute to reducing inequalities: some causes of unjustified and preventable suffering cannot be addressed without first making them visible. It is important to note that surveillance does not exempt participants from risks; for this reason, surveillance often raises ethical dilemmas, such as issues of privacy, autonomy, equity, and the common good, which must be constantly considered and balanced (this knowledge can be a challenge in practice)6.

In 2002, WHO Director-General Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland launched the Ethics and Health Initiative, which has since become a reference for ethics activities across the organization. Most recently, in 2017, the WHO Guidelines on Ethics in Public Health Surveillance were published6, constituting the first framework to help policymakers and practitioners address the ethical aspects of public health surveillance. In this regard, public health surveillance may limit privacy and other civil liberties. For example, during a pandemic, surveillance may lead to mandatory quarantine, isolation, or confiscation of property, affecting in various ways particular interests for the benefit of the vast majority. In other circumstances, surveillance may include reporting based on names or lifestyles. When the population is aware of all this, it can generate deep concern for invasion of privacy, discrimination, and stigmatization7. Therefore, it is necessary to include ethics in all the work carried out by public health as an instrument of the State in the light of preventing infectious diseases.

Principles of equity and justice

For several decades, the lack of resources for research on diseases that constitute a major public health problem has been described. In what is known as the 10/90 distribution, it is estimated that only 10% of the research resources are allocated to diseases that represent 90% of the conditions; if not controlled, these diseases could wipe out the population8. This phenomenon is also present in bioethical research, where existing justice problems regarding infectious diseases have not been addressed properly. This situation is linked to the particular interest of a public whose economic and moral condition directs its preferences toward curing diseases that afflict or kill most of the population immersed in a state of worrying poverty. Issues such as euthanasia (even for children), eugenics, abortion, assisted reproduction, pre-natal genetic diagnosis, gene therapy, and the doctor–patient relationship are left on a primary level. In contrast, infectious diseases occupy a secondary place to the agenda of the countries with the greatest potential for global impact.

M. Selgeid pointed out some consequentialist reasons for urgent attention to infectious diseases from an ethical point of view8. The main reason is the devastation caused worldwide by the arrival of an infectious disease that becomes a pandemic in a matter of weeks (the death toll will be remembered as evidence that a pandemic can kill more people than two world wars). This underlies health surveillance and ethical dilemmas. To name just a few dilemmas, we find the allocation of scarce resources, social justice, treatment experimentation, voluntary infection of healthy participants for vaccine development, population-based studies without individual informed consent, access to medical care, treatment inequity, forced quarantine and isolation, among others. Finally, the author emphasizes that all these problems arise not only from the biological aspect of the pathogen but also from the social conditions that characterize modernity, such as the condition of vulnerability generated by poverty and inequality worldwide (those who suffer and die most from diseases are those who face this condition). Therefore, the consequentialist vision warns of the risks to carry out correct epidemiological control on a global scale. This implies carrying out various bioethical studies that address the dilemmas without waiting for another infection with the capacity to devastate humanity8.

Various epidemics are known to have caused the deaths of thousands to millions of people; they have been some of the worst disasters and have even changed the course of history. The Black Death, which wiped out one-third of Europe’s population between 1347 and 1350, was one such epidemic that caused the world to search for solutions and inspired a wide variety of painters, poets, and writers. By changing the mentality of the world’s inhabitants, the world did not return to what it was, thus contributing to the arrival of the Renaissance. Another example was when the flu killed between 20 and 100 million people in 1918. Although we have more medical technology today, it does not guarantee total suppression of the constant threat of mass death since there are no vaccines for many deadly diseases with pandemic potential, nor are there hospital beds and ventilators for everybody in the world. This should inspire society to analyze the bioethical aspects of medical decisions to be made in such situations and even to evaluate preventive measures that can sometimes be intrusive for the general population.

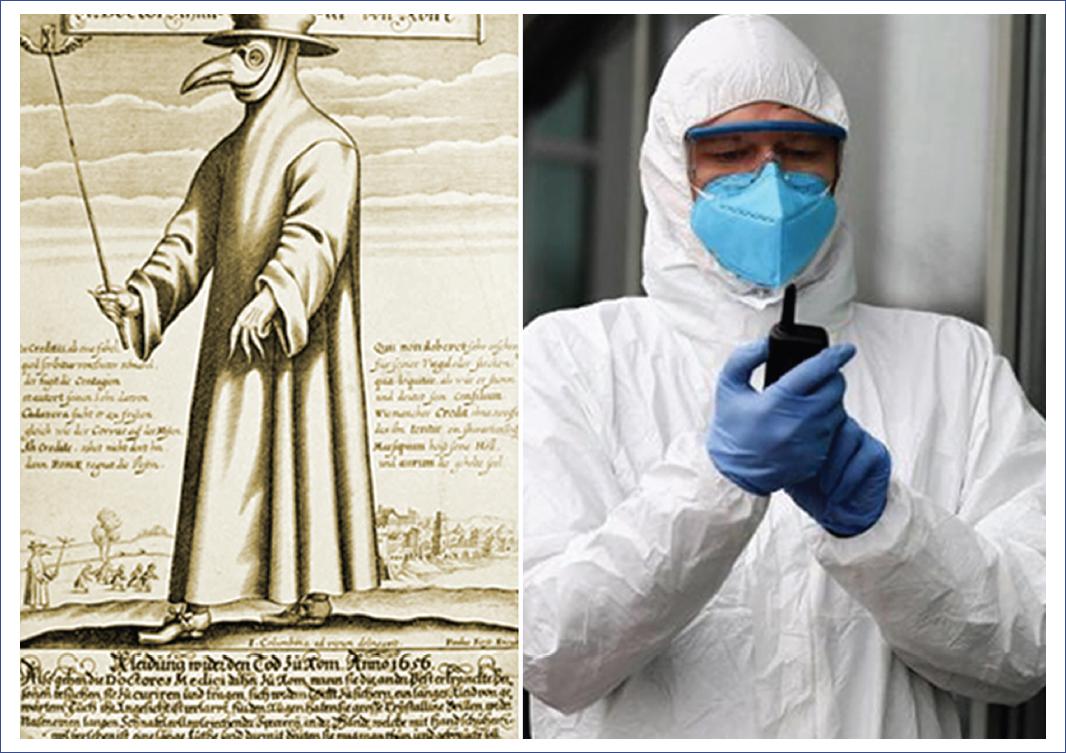

Another example is severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a viral respiratory disease caused by the SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV). SARS was first reported in Asia in February 2003. Within months, the disease spread to more than two dozen countries in North and South America, Europe, and Asia. Before the global outbreak could be contained, 8,098 people worldwide were infected by SARS during the 2003 outbreak, of whom 774 died9. Unfortunately, we did not heed the warning, and in 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, first reported in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019. To date, 15 million people have died (estimate for the period January 1, 2020, to May 5, 2022), reflecting the pandemic’s impact on many areas (economic, social, emotional, and moral, among others). The world has been paralyzed with fearful and bewildered gazes at something health authorities and citizens saw coming, even if they were unprepared to face it. A new pandemic is inevitable, and the wisest thing to do is to be prepared not only technologically but in terms of the ethical aspects of decision-making that caused so much turbulence and disagreement during that time (Fig. 1).

Another latent pathogen that has been identified as a devastating killer is smallpox. Before its eradication, smallpox ravaged humanity for at least 3,000 years, killing 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Although the WHO declared the disease eradicated in May 1980, humanity is not out of danger, as some countries openly claim to have frozen strains for military purposes (they could be used as biological weapons). In this context, the vast majority of the population is unprotected, as smallpox vaccination has been suspended for 50 years. Smallpox is a historic milestone that underscores the urgent need to invest in global health security and equitable universal health coverage (WHO, December 13, 2019).

Today, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic demonstrates how devastating and unfair an infectious disease can be. According to statistics published by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, in 2021, 37.7 million (30.2 million-45.1 million) people were living with HIV, of whom 1.7 million (1.2 million-2.2 million) were children (up to 14 years of age), and only 28.2 million people had access to antiretroviral therapy by the end of June 2021. Since the beginning of the epidemic, 79.3 million (55.9 million-110 million) people have been infected with HIV, and 36.3 million (27.2 million-47.8 million) people have died from AIDS-related illnesses. At this point, the problem lies in the inequitable distribution of global resources to care for the sick. It is not the same to contract HIV in sub-Saharan Africa as it is in the United States; ultimately, the prognosis and quality of life are incomparable, further widening the existing inequality gap.

It is estimated that just over half of the world’s people living with HIV live in sub-Saharan Africa, and a very high percentage of the world’s AIDS deaths occur in this region. Most people in these countries live in extreme poverty and, therefore, do not have access to new medications to fight HIV/AIDS. However, the problem extends to other areas of public health, as people in the region lack access to medicines to prevent and control common diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and meningitis; in fact, 50% of the population in these countries lack access to medications as basic as aspirin or acetaminophen, not only vaccines.

Misfortune or injustice? The problem is not only HIV/AIDS and other deadly infectious diseases but also access to the other components of health, such as living conditions, labor, undocumented migrants, poor education (where it exists), prostitution, and poor nutrition; each contributes to the AIDS epidemic, and each is at least in part the result of historical practices related to racist and abusive colonial oppression (certainly the AIDS epidemic in South Africa should be attributed in large part to historical social injustice).

The current head of WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (2022), emphasizes the urgent need for all countries to invest in more resilient health systems that can maintain essential health services during crises, including robust information systems. The question is how. No amount of money is enough for rich countries, much less for those in emerging and developing countries. Ultimately, the problem does not end them. Consequently, everyone is responsible for working together for the good of all, even across borders, according to ethical principles of justice and equity.

Monitoring individuals or groups who are particularly vulnerable to disease, harm, or social injustice is critical and requires careful consideration to avoid imposing unnecessary additional burdens on those already affected. Vulnerability may be generalized, affecting large communities (entire countries) with limited economic development, limited access to health facilities, educational deficiencies, occupational hazards, or greater social disadvantage. Thus, to promote equity, public health surveillance should focus on the specific problems of those vulnerable communities that are particularly vulnerable to disease, harm, or injustice (such as homosexuals and undocumented migrants) and that are at greater risk of experiencing other burdens, such as discrimination and stigma, as a result of surveillance activities. Therefore, a plan should be implemented to reduce, eliminate, or compensate for any harm from these activities6.

Some countries may not have the capacity to establish and maintain public health surveillance of sufficient quality, even for high-priority goals that could significantly reduce health inequalities and improve the health of their populations due to severe resource constraints. The principles of equity, justice, and solidarity provide the ethical basis for requests for international assistance. The global community – international health organizations, non-governmental organizations, major foundations, and countries playing a leading role on the world stage – has an ethical responsibility to work with and support these countries in public health surveillance and subsequent interventions. This global justice requirement aims to reduce health inequities among countries and improve global health for the benefit of all, including high-income countries. Since disease outbreaks and risk factors do not respect borders, the global community should also be interested in having sustainable surveillance systems in place, even in countries that do not have the resources to establish and maintain them10.

Surveillance may require not only technical support but also formal ethical evaluation and improvement on a systematic basis, as demonstrated by international support for research ethics training. Where countries fail to protect the fundamental rights or interests of vulnerable individuals and populations in public health surveillance, international support should be conditioned to the correction of such violations and breaches. International humanitarian organizations have expressed deep concern that surveillance often responds to the needs of high-income countries, creating ambiguity about the primary beneficiaries of surveillance11. For example, malnutrition may be a priority in a poor-resource country (such as those in Latin America or Africa), while international donors may consider it a lower priority than an infectious disease outbreak. In other words, they may not be as concerned about children starving to death as they are about Ebola or multidrug-resistant tuberculosis not spreading to their country because of the potential impact on their population (and economy). While famine does not perpetuate diseases that can cross borders, poverty contributes directly. True partnerships may require reforms in global health governance to shift the priority from security, political, and trade interests to “universal health values”12.

The problem is the global lack of equity and justice in the right to health, given that the greatest investments in preventive interventions are made in countries that have more capital (they can contain the spread of disease). For this reason, WHO member states must create conditions that allow all people to live as healthy as possible.

Health problems tend to affect vulnerable and marginalized groups to a greater extent, so States must take steps to move toward realizing the right to health following the principle of progressive realization. This means that once the State has provided the minimum necessary for everyone, it must take deliberate, concrete, and specific measures to maximize its available resources. These resources include those provided by the State and those derived from international assistance and cooperation, continuously taking the necessary steps to move as rapidly as possible toward the full and effective enjoyment of each of the economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR).

States recognize the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Therefore, as an acquired right, following the basic floor and for the sake of the principle of progressive realization, the State is internationally obliged to increase the necessary measures to achieve the highest standard of the right to health, which cannot be achieved in a short period. In this regard, flexibility is needed to reflect the realities of the world and the difficulties each country faces in ensuring its effectiveness.

The principle of progressive realization should be understood as a gradual and constant advance whereby States, based on their international commitments, take the necessary and appropriate measures to progressively achieve the full realization of ESCR, investing to the maximum of their available resources without taking regressive steps. Therefore, the protection achieved concerning the human right to health must be respected and strengthened based on the principle of progressivity since States have an absolute obligation to ensure the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health13.

The common good and individuality

An individual with a communicable disease threatens the health of those around. Prevention and control measures are necessary to stop its spread, including mandatory testing, vaccine administration, health department notification, contact notification, isolation, quarantine, travel restrictions, and many others. Any of these measures may violate human rights, the principle of autonomy, and the individual’s freedom. This ethical dilemma seems easy to resolve if one is inclined to defend that public health is the greater good because it is communitarian and above individual rights, including the privacy of subjects and non-maleficence over an individual’s autonomy. For example, if a patient is found to have multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, all contacts should be tested to detect other cases and interrupt the spread. In this case, it should not be an option to go to the clinic to have everything done and be treated. However, it is assumed that in a free and tolerant country, an individual should be allowed to refuse tests to rule out or diagnose an infectious disease that could harm society.

For many philosophers, public health experts, economists, and bioethicists, to find a balance between the legitimate rights of the sick individual and the social conflict represented by the risk of spreading the disease is challenging. Knowing oneself to be free and autonomous implies being respectful of the freedom of others and acting conscientiously. The State has the obligation to respect our choices as long as they do not violate other people’s rights. The State’s obligation is to protect the civil rights of citizens: to live, practice their beliefs, and have lifestyles as they see fit without harming others. Even if they are not “best practices,” the idea that should prevail is that all citizens, regardless of their lifestyles, should live together in complete equality, respecting the rights of others. This idea would be the threshold from tolerance to respect for individual rights and the preservation of a democratic society. However, reaching the threshold would not be practical.

The answer is not simple. For example, implementing a quarantine policy would be accepted differently in each community, depending on the conditions of democracy, cultural plurality, and social inequality. In some countries, failure to comply with isolation or quarantine rules is considered a crime; in other countries, quarantine could be carried out with voluntary cooperation and conditions as unrestrictive as possible, but social participation is essential in both cases. Vaccines pose a similar problem: some countries enforce the use of vaccines, while others respect the choices of individuals, even though their choices puts their health and that of the rest of society at risk, increases the cost of care, and limits public health resources. Why shall we sacrifice individuality? The short answer is for the common good (from the Latin, bonum commune), which generally refers to the well-being of all members of a community and also to the public interest, as opposed to private benefit and particular interest. Although many theories justify the common good, it is not the purpose of this text to explain them in detail; however, they all seek the welfare of the community for the good of all its members, with the participation of all.

Since the early modern period, the common good has been conceived in contractual terms (initially defined in terms of the social contract: for Hobbes, the securing of peace; for Locke, the protection of fundamental rights and individual property; for Rousseau, the general welfare and the preservation of the good condition of the members of society). However, these and other purposes of the common good require the consent of the members of society.

Liberalism produces social integration only formally and through the law, but not through goods defined by their communitarian character or the common good. Consequently, it constructs political legitimacy only through procedures rather than communication among citizens about common goods. Communitarians emphasize a person’s connection to the community: his or her existence is essentially defined by his or her social roles, interactions, and interpersonal relationships, while his or her identity is primarily shaped by shared understandings, that is, the culture and historical traditions of the community in which he or she was born and lives. Communitarians believe in creating order by blending the impartiality of the liberal rule of law and the universality of human rights that transcend gender, race, ethnicity, and political beliefs with the partiality of the common good or community goals as defined within the community itself.

How, then, does the community deal with dissidents and cultural minorities? It grants them the right to dissent regarding opinions and ways of life since “the struggle for recognition can find only one satisfactory solution, which is a regime of mutual recognition among equals”14,15.

The principle of accommodation suggests that some individuals (usually minorities) should sometimes be exempted from certain laws of general application on the grounds of conscientious objection. The scope is much debated, but it is clear that some degree of accommodation is necessary to protect the equality of minorities.

This amplified discrimination may affect some members of the community more than others, particularly women, indigenous peoples, children, persons with disabilities, older adults, and LGBT intersex (LGBTI) people6. It is, therefore, essential to implement an age, gender, and diversity approach to meet the commitment to ensure that all health protection activities, including durable solutions, are accessible to and inclusive of all minorities.

Minorities are vulnerable to violations of their rights to identity, non-discrimination, and effective participation. These principles must also be guaranteed in forced displacement and isolation situations, as they may be socioeconomically and physically isolated. A high level of protection can only be achieved through an inclusive and participatory approach. The involvement of members of minority and indigenous groups in policy formulation and consultation processes is key to the development and implementation of appropriate solutions to the problems they face. Consultation and participation are essential in all phases of crisis and prolonged situations. The State’s duty is to ensure that these minorities have the necessary information for their participation to be meaningful and consistent with the common good16.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)