Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is a specialty that has grown in recent years due to the need to provide comprehensive and interdisciplinary care to patients diagnosed with life-threatening illnesses, usually chronic, degenerative, incurable diseases with a profound impact on the quality of life of patients and their families. In these cases, the physician has to initiate comprehensive management focused on symptom control, suffering reduction, and appropriate treatment from the time of diagnosis until the end of life or eventual cure.

Pediatric palliative care undoubtedly differs from adult palliative care1,2. The treatment plan in palliative care should always be individualized and focused on the patient and the family to achieve better outcomes, always keeping in mind that "the goal is to add life to the child´s years, not just years to life"; thus, the quality of life, not survival, becomes the priority3. However, barriers still exist at the cultural, educational, economic, and regulatory levels, even within the medical field.

One of the most frequent complications in terminally ill patients is infection, including respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal tract infections, wound infections, and bacteremia. Urinary antibiotics reduce dysuria, in contrast to respiratory infections, for which opioids are preferred because they provide better symptom control (dyspnea or sensation of suffocation)4. Up to 90% of hospitalized patients with advanced cancer are treated with antibiotics during the last week before death4-10. These infections are frequent due to their immunocompromised status, and the symptoms of sepsis can be similar to those seen at the end of life. However, research has shown that antibiotics are often used in these patients in the absence of clinical signs consistent with bacterial infection, often due to lack of judgment in end-of-life medical decision-making6.

In the advanced stages of oncologic disease, healthcare professionals and patients (and their families) are faced with difficult decisions regarding treatment and general medical care. However, in palliative care, the use of antibiotics always presents an ethical dilemma. Deciding whether to initiate or withdraw treatment for an infection can be difficult at this stage of the disease in the face of a poor short-term prognosis. Although the administration of antibiotics may lead to adverse outcomes, two benefits (increased survival and symptom relief) are the main reason why their use is indicated and justified10. Therefore, the medical actions within the doctor-patient relationship should be defined as follows:

− Mandatory. Those that cannot be denied to any patient. For example, hydration and nutrition.

− Permitted. Those that may be beneficial to the patient. For example, the administration of antibiotics and mechanical ventilation.

− Ethical. Those that should be given to all terminally ill patients. For example, control of pain and other terminal symptoms.

− Unethical. Those that should not be given to any patient. For example, repeated resuscitation and malicious procedures.

Terminal oncologic disease is defined as advanced, irreversible, and progressive oncologic pathology with no reasonable chance of cure and failure of established treatment, with changing evolution of symptoms over time, multiple complications, loss of independence, emotional impact on the patient, family, and healthcare team, and a short survival time (in children it is not limited to 6 months as in adults). Some treatments are considered exceptional in a patient with terminal cancer and their administration should be individualized because of their doubtful benefits, such as dialysis, mechanical ventilation, use of amines, cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers, transfusions, and broad-spectrum antimicrobials. Although these are permissible interventions, they can become unethical because of the potential harm they could cause to the patient since they are not curative treatments and would only be permissible if they improved comfort and well-being during the remainder of life.

Thus, the debate continues as to whether these drugs are effective in reducing uncomfortable symptoms, improving the quality of life, and prolonging survival, or on the contrary, they only prolong the process of death and add more sources of suffering. Additional problems with the use of antibiotics include the need to ensure intravenous access, increasing the risk of adverse effects, pharmacologic interactions, Clostridium difficile infection, the risk of acquiring or generating multidrug-resistant microorganisms, in addition to causing significant costs to health and family resources, financially and emotionally.

Healthcare resources are always scarce and must be allocated equally and fairly to all patients, but most importantly, to benefit the patient without causing avoidable harm. There is a financial burden when resources are not allocated appropriately, but this pales in comparison to the emotional burden on the patient, family, and healthcare team.

Expenses of the family accompanying the hospitalized child also increase (eating out, transportation, paying for showers for personal hygiene, abandoned siblings, absenteeism from work, and funeral expenses, which are higher when they come from the province). This becomes irrelevant when hospitalization is aimed at improving the vital and functional prognosis but becomes more difficult in the case of terminally ill children, when death is inevitable and expected. These treatments are known as potentially inadequate treatments: although they have an effect, they do not offer a benefit because they do not improve vital function or prognosis.

The above can be clarified by the following example: Consider the case of a 13-year-old male patient with Ewing´s sarcoma and a history of hip disarticulation two years prior. At present, the patient has a recurrence in the lumbar spine and unresectable pulmonary metastases affecting approximately 60% of the lung. He is also diagnosed with pulmonary aspergillosis and is currently receiving palliative radiation therapy. The patient is admitted to the hospital due to respiratory failure and fever and diagnosed with septic shock due to pneumonia, given that he is an immunocompromised patient. Mechanical ventilation and amines are required, and an antimicrobial regimen is initiated. However, after 72 hours with no response and positive blood cultures, the therapeutic approach was changed. In this example, it is important to note that the use of antibiotics will not change the prognosis, which is unfavorable in the short term (no apparent benefit). In addition, escalation of the antimicrobial regimen in response to a pneumonic process is considered ineffective, given the high risk of mortality even with all available antimicrobial therapies.

On the one hand, the physician has to decide to continue or discontinue treatment. However, this decision impacts the patient and his family because of the hope that the treatment will be effective, but has no legal or ethical justification and is known as therapeutic obstinacy.

On the other hand, the physician finds himself in the situation of having to make decisions at the end of the patient´s life. In this context, it is essential to have more solid guidelines or criteria to help them in their decision-making process. In addition, it would be highly advisable for physicians to seek the advice and collaboration of the hospital´s bioethics committee to address and deliberate on the therapeutic dilemma they are facing.

The use of antibiotics is supported and documented as one of the last therapeutic approaches to be withdrawn from terminally ill patients with advanced cancer, in contrast to other interventions, such as artificial nutrition, invasive mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, and blood transfusions, which are considered extraordinary in this context5. Although the reason for this trend is not well understood, the use of antibiotics is probably perceived as a procedure that only requires the availability of the drug and adequate access for its administration (whether intravenous, intramuscular, or oral). This may give the impression of being a less invasive approach and, at the same time, give physicians some moral comfort in feeling that they are doing something to prevent the death of a terminally ill patient.

To date, studies of antibiotic use in patients with terminal illnesses have focused primarily on adults. However, the results of these studies are limited and do not provide a solid basis for determining whether the use of antibiotics in this stage of life is beneficial in reducing symptoms, improving quality of life, or prolonging survival. Moreover, it is not possible to say with certainty whether using antibiotics in this setting could lead to further complications.

This study aimed to analyze the characteristics of pediatric patients with terminal cancer who were hospitalized shortly before their death. The purpose of this research is to encourage future studies that can provide guidelines and recommendations for the management and prescription of antibiotics in the last stage of life of these patients. In addition, we sought to describe the characteristics of children and adolescents with terminal oncologic diseases who received antibiotics during their hospitalization at the Palliative Care Program of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez between 2018 and 2020. This analysis aims to facilitate shared decision-making between health professionals and patients´ families under these circumstances.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive, retrospective, cross-sectional study that included patients aged 0 to 18 years with terminal oncologic diseases. These patients were admitted to the palliative care program of the tertiary level hospital (Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez) and were hospitalized during their last 5 to 7 days of life. The study period was from January 2018 to January 2020.

Data collected included demographic variables, primary and secondary diagnoses, total days of hospitalization, cultures obtained, antibiotics used in the last 5 to 7 days of life, symptoms presented in the last week of life, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order signatures, and principal diagnosis at the time of death.

Drug data were collected from medical progress notes and nursing notes, categorized by therapeutic class using the NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics) Multum Lexicon database. Category 2 and 3 antibiotics were identified and grouped based on their chemical structure.

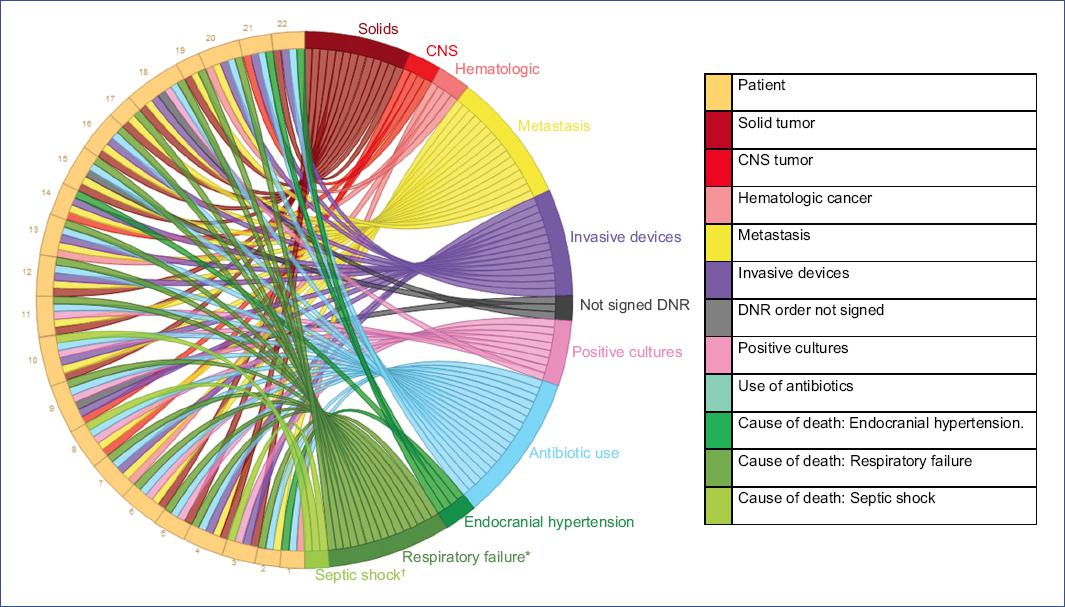

Descriptive statistics were performed using frequencies and percentages and a chord diagram with the program Chordial Version 1.2 for MAC.

Quantitative variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges and compared according to the baseline oncologic disease.

This research study followed the ethical norms of our institution and the Ley General de Salud (General Health Law) of 2016, in its eighth title bis, "palliative care for the terminally ill", as well as the Nuremberg Declaration of 1947, which establishes the ethical conditions for research on human beings. This declaration was amended in 1964 during the World Assembly in Helsinki and updated for the last time in 2000 in Edinburgh.

Results

During the study period, from January 2018 to January 2020, 90 children with cancer died. These children were part of the palliative care program, and not all children with cancer admitted at the hospital were enrolled. From the total number of deaths, we excluded 16 patients who were in the agonal phase, less than 7 days before death, and 48 children who died at home. These 48 children who died at home did not receive antimicrobials in the last 7 days before death. This left us with a group of 26 patients who died in the hospital, of whom we could obtain complete information from 22 files.

Twenty-two patients were included, of whom 18 (81%) received antibiotic treatment. The mean age of the patients was 8.75 years (interquartile range: 6 months to 18 years), with no sex predominance (1:1 ratio). As for the underlying oncologic pathologies, 19 (86.3%) were found to be solid tumors. Of these, central nervous system tumors were found in seven patients (31.81%), followed by neuroectodermal tumors in four patients (18.18%). Hematologic malignancies in three patients (13.6%), mainly leukemia in two patients (9.09%); 16 patients (72.72%) had metastases.

In our study population, 18 patients (81.81%) had an infection documented in their medical records, including bloodstream infection identified as septic shock, septicemia, or nosocomial sepsis in 11 cases (49.98%), followed by pneumonia in three patients (13.63%). Of these 18 patients, empiric therapy was initiated in 16 (88.88%), while two patients (11.1%) without an infectious diagnosis received treatment. A total of 18 patients (81.8%) were treated with antimicrobial therapy (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1 Patient characteristics and the use of antibiotics (n = 22)

| Characteristic | Total | % | Use of antibiotics | % | Non-use of antibiotics | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 22 | 100 | 18 | 81.81 | 4 | 18.18 |

| < 6 months | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months -1 year | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.54 |

| 2-5 years | 5 | 22.7 | 5 | 22.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 6-10 years | 4 | 18.18 | 3 | 13.6 | 2 | 9.09 |

| > 11 years | 11 | 50 | 9 | 40.90 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 11 | 50 | 8 | 36.36 | 3 | 13.6 |

| Male | 11 | 50 | 10 | 45.45 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Primary oncological diagnosis | ||||||

| Solid tumors | 19 | 86.3 | 15 | 68.18 | 4 | 18.18 |

| Nervous system | 7 | 31.81 | 4 | 18.18 | 3 | 13.6 |

| Neuroectodermal tumor | 4 | 18.18 | 4 | 18.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Osteosarcoma | 2 | 9.09 | 2 | 9.09 | 0 | 0 |

| Ewing´s sarcoma | 2 | 9.09 | 2 | 9.09 | 0 | 0 |

| Carcinoma of the cecum | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Retinoblastoma | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal tumor | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Hematological | 3 | 13.6 | 3 | 13.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukemia | 2 | 9.09 | 2 | 9.09 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Metastasis | 16 | 72.72 | 13 | 59.09 | 3 | 13.6 |

| Infectious diagnosis | ||||||

| Septic shock | 5 | 22.72 | 3 | 13.63 | 2 | 9.09 |

| No infectious diagnosis | 4 | 18.18 | 2 | 9.09 | 2 | 9.09 |

| Pneumonia | 3 | 13.63 | 3 | 13.63 | 0 | 0 |

| Septicemia | 3 | 13.63 | 3 | 13.63 | 0 | 0 |

| Nosocomial sepsis | 3 | 13.63 | 3 | 13.63 | 0 | 0 |

| Encephalitis | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Intussusception | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervical abscess | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Cause of death | ||||||

| Respiratory failure | 9 | 40.9 | 8 | 36.36 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Endocranial hypertension | 4 | 18.18 | 3 | 13.63 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 3 | 13.63 | 3 | 13.63 | 0 | 0 |

| Septic shock | 2 | 9.09 | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Pleural effusion | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute pulmonary edema | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiorgan failure | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Spontaneous tension pneumothorax | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Total days of hospital stay | ||||||

| 8-30 days | 9 | 40.90 | 8 | 36.36 | 1 | 4.54 |

| > 30 days | 7 | 31.81 | 4 | 18.18 | 3 | 13.63 |

| < 7 days | 6 | 27.27 | 6 | 27.27 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalization Service | ||||||

| Oncology | 13 | 59.09 | 12 | 54.54 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Neurosurgery | 5 | 22.72 | 2 | 9.09 | 3 | 13.63 |

| Intensive Care Unit | 4 | 18.18 | 4 | 18.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive cultures | 9 | 40.90 | 8 | 36.36 | 1 | 4.54 |

| Use of invasive devices | ||||||

| None | 8 | 36.36 | 6 | 27.27 | 2 | 9.09 |

| 1 | 4 | 18.18 | 3 | 13.63 | 1 | 4.54 |

| 2 | 4 | 18.18 | 3 | 13.63 | 1 | 4.54 |

| 3 | 5 | 22.72 | 5 | 22.72 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of amines | 7 | 31.81 | 7 | 31.81 | 0 | 0 |

| Infectious diseases assessment | 11 | 50 | 7 | 31.81 | 4 | 18.18 |

Figure 1 Chord diagram. The left side of the graph refers to the n = 22 patients analyzed. On the right side, the colors represent their characteristics.*In respiratory failure, other causes such as pleural effusion, acute pulmonary edema, spontaneous tension pneumothorax, pulmonary hemorrhage were included.†In septic shock, multi-organ failure was included.CNS: central nervous system; DNR: do not resuscitate.

The most common factors found for increased antibiotic use were ICU admission (100%) and association with amine use (100%).

The most frequent symptom that led to the initiation of antimicrobial therapy was shortness of breath (15 patients, 68.18%), followed by pain (11 patients, 50%) and fever (nine patients, 40.9%). Despite the initiation of antibiotic treatment, these symptoms persisted in nine (60%), two (18.18%), and five patients (55.5%), respectively (Table 2). The most frequent cause of death was respiratory failure (nine patients, 40.9%), followed by endocranial hypertension (four patients, 18.18%). Of all patients included, 19 (86%) signed a DNR order, 11 (50%) in the last week of life, and 8 (36.3%) more than one week before death.

Table 2 Symptoms and signs during the last 5 to 7 days of life and 24 h before death (n = 22)

| Symptoms 5 to 7 days before death | n | % | AB use of total patients who had the symptom | n | % | Persistence of the symptom 24 hours before death | n | % | Yes | % | No | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tachycardia | 18 | 81.81 | Yes | 14 | 77.7 | ⟶ | 18 | 100 | 14 | 77.7 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 4 | 22.22 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 22.2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Breathing difficulty | 15 | 68.18 | Yes | 12 | 80 | ⟶ | 10 | 66.6 | 9 | 60 | 3 | 20 |

| No | 3 | 20 | 1 | 6.66 | 2 | 13.33 | ||||||

| Pain | 11 | 50 | Yes | 9 | 81.81 | ⟶ | 2 | 18.18 | 2 | 18.18 | 7 | 63.63 |

| No | 2 | 18.18 | 0 | 2 | 18.18 | |||||||

| Fever | 9 | 40.9 | Yes | 8 | 88.8 | ⟶ | 6 | 66.6 | 5 | 55.5 | 3 | 33.3 |

| No | 1 | 11.11 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Purulent discharge | 2 | 9.09 | Yes | 2 | 100 | ⟶ | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Cough | 2 | 9.09 | Yes | 1 | 50 | ⟶ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

| No | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 | ||||

| Wound dehiscence | 1 | 4.54 | Yes | 1 | 100 | ⟶ | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

AB: antibiotic.

Discussion

Several studies in adult oncology patients show that antibiotics are frequently prescribed at the end of life4,11 and that the most common infections are respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal infections, wound infections, and bloodstream infections. In contrast, our results showed that the most frequent cause was sepsis without focus, followed by pneumonia. Additionally, opioids have been described as a more convenient option than antibiotics for treating dyspnea and pain, providing better symptom control and more comfort10,12. Although there are several publications on antibiotic management in patients nearing the end of life, these are small observational studies highlighting the lack of symptom control despite initiating an antimicrobial regimen in the final phase of life. These findings motivate healthcare professionals to escalate the therapeutic approach13-16. Other retrospective pilot studies have attempted to evaluate the potential benefit of broad-spectrum antibiotics in hospitalized patients during the last week of life in the terminal phase of the disease. These studies found a significant empirical use of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy in these patients. Although treatment modalities at the time of consultation may reflect the medical team´s efforts to manage potentially reversible complications, including possible infections, a high rate of empiric treatment predominates. This difference is hard to identify14,17, especially in patients with persistent symptoms such as fever or dyspnea. The decision to escalate antibiotic treatment is often based on a critical pathway rather than clear evidence of an infectious process. Therefore, this treatment sometimes fails to completely control the symptoms that led to the patient´s admission, as observed in our study. However, microbiological evidence of infection was found in almost half of the patients studied justifying, at least in part, the initiation or escalation of antibiotic treatment. This approach should be accompanied by comfort measures and appropriate tailoring of the therapeutic effort to facilitate decision-making.

It is ethically unacceptable for patients to receive treatments not indicated according to their clinical situation. Therefore, it is essential to adapt the diagnostic, therapeutic, and monitoring strategies to each patient´s specific clinical condition and needs at each moment of their evolution, defining the objectives of their care and acting accordingly. For the analysis of the patient´s clinical history, it is essential to involve all the specialists and professionals of different disciplines who participate significantly in the child´s care (oncologist, palliative pediatrician, infectious disease specialist, among others). Each specialist´s particular and specific perspective adds depth to the analysis and avoids omitting aspects that could be important for decision-making18-21. Thus, in this study, 19 of the patients had signed DNRs, which indicates that the attending physician, together with the family, was aware of the expected fatal outcome of the disease and the risk of death in a short period; however, it gives the impression that the signing of the DNR order did not influence the decision to initiate antimicrobial therapy. The chord diagram shows that only three patients did not sign the DNR.

Multiple complications can accompany the disease and its end, such as infections, which are the most frequent.

Although survival was not evaluated in this study because, unfortunately, all patients died, the study by Reinbolt et al.22 found no significant differences in survival between patients with or with no diagnosed infection nor between those who received antimicrobials and those who did not.

The patients analyzed in our study had an underlying pathology with no reasonable cure options and were expected to die within a limited period, were enrolled in the palliative care program, and had signed advance directives that included the DNR order. This population is very specific and cannot be compared to patients with life-threatening oncologic pathology who may still have options for cure and may die from complications of the disease or treatment. In terminally ill patients, infectious complications may occur even as part of the natural history of the disease and the end of life, and their aggressive management may not change the outcome, which is death. This is not because of the infectious process but because of the underlying pathology. For example, consider a patient diagnosed with extensive brainstem glioma admitted for apnea and respiratory failure. If this patient is diagnosed with pneumonia, antibiotic treatment may be initiated because of the clear presence of infection. However, the benefit of this treatment is questionable. The main cause of respiratory failure comes from the central nervous system and is intractable. In this context, antibiotics become a futile treatment to address the primary cause of hospitalization. Such situations pose an ethical dilemma of a utilitarian and deontological nature. For example, antibiotic treatment could improve symptoms related to infection15. In this series, fever and dyspnea improved only 33.3% and 20%, respectively, in those who received antimicrobials, which aligns with palliative care goals. However, these symptoms may improve with other non-antibiotic therapies such as sedatives, anxiolytics, antipyretics, and opioids, considering that even specific symptoms of infection, such as purulent discharge or wound dehiscence, did not improve in the study. In these patients, the goal is to control or attenuate the uncomfortable symptom. Although care must be taken to treat the cause of the symptomatology, it may not be treatable due to the advanced nature of the underlying disease, making it necessary to redirect the goals of therapy to improve the comfort and quality of life of patients and their family. The real challenge is to distinguish between patients who will benefit from vigorous antimicrobial therapy and improve their quality of life and those who will not benefit and whose death is inevitable and even the initiation of antibiotic therapy may be harmful, prolonging life with pain and greater suffering19-21.

The Hippocratic tradition becomes the starting point of ethical rules in the practice of Western medicine. It is important to emphasize the principle of not doing harm, which can be done in different ways, either through action (imprudence, ignorance, and inexperience), omission (negligence), or inadequate risk management due to failure to foresee the possibility of occurrence of these events in advance. Healthcare professionals should actively seek continuous communication with the family and the patient throughout the course of the disease, especially in the final stages, to inform about the existence of viable therapeutic alternatives according to the diagnosis, evolution, symptoms, and prognosis, in an individualized manner, without attempting to standardize management for patients with specific characteristics20-23. The lack of clear guidelines regarding the use of antibiotics in terminally ill oncology patients leads to unnecessary overuse of antibiotics, with the possibility of delaying death and perpetuating poor quality of life, discomfort, and dysthanasia. In cases of serious medical doubt regarding prognosis, a time trial with well-defined objectives and specific goals of antibiotic use should be performed, which may reduce the anxiety of medical staff and family.

This study has a limited population sample. Its main aim is to draw attention to the importance of further research into medical decision-making at the end of life in pediatric patients with oncological diseases. It is important to identify who may benefit from using antimicrobials and thus prevent serious harm associated with their administration.

To address this dilemma, we should conduct further research focused on comparative analyses of treatment burden versus cost/benefit regarding antibiotics. It is also important to identify predictive variables that can tell us which patients might benefit from these treatments and to what extent. Importantly, each decision must be made from an individual perspective, considering the circumstances and preferences of the patient and family. It is essential to maintain constant communication and to ensure that medication is part of a comprehensive therapeutic approach in which the goals of care are transparent and defined.

This study has some limitations, including the small sample size and the presence of incomplete records that do not include the symptoms or antibiogram reports needed to determine the susceptibility of the isolated organisms. The lack of clear guidelines on the use of antibiotics in children with terminal oncological diseases may lead to unwarranted prescriptions. This may result in increased patient discomfort due to hospitalization, the need for intravenous access, and additional tests, among others. These interventions may unnecessarily prolong the patients life, and delay an inevitable death, which may lead to dysthanasia.

The medical team should not underestimate DNR order by the family and the physician responsible for the patient in a palliative care setting. It warns against potentially inappropriate medical therapies for little or no expected benefit to the patient. The possible lack of antimicrobial efficacy in reducing symptoms, the increased burden on the patient, family, and healthcare system must be considered on an individual basis.

Respiratory failure as the main symptom triggering the initiation of antimicrobial therapy and as the first cause of death does not necessarily reflect an underlying infectious process and could even be considered the first symptom of the onset of agony.

Admission to an intensive care unit requires intensive use of all available medical and human resources. Therefore, the admission of patients with terminal oncological pathology who are already part of a palliative care program and who have signed a DNR order is not recommended. However, if admission is considered, it should be carefully weighed against the objective risks and benefits, considering the prognosis associated with the primary disease. An alternative could be to subject these patients to therapeutic trials with defined timelines for the use of antimicrobial therapies. The clinical results of these trials will guide the decision to adjust or maintain previously established treatment.

What is really important is the clinical-ethical analysis of whether the initiation or withdrawal of antibiotic therapy is an appropriate treatment at this stage of life, a difficult task that involves not only the medical perspective in terms of knowledge but also the ethical and moral perspective of the responsible physician.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)