Introduction

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) is a rare inflammatory skin disease of unknown etiopathogenesis. It is characterized by papulosquamous lesions or erythematous-squamous plaques affecting the trunk and extremities; sometimes, it is accompanied by pruritus, or it can also be asymptomatic1.

PLEVA is characterized by initially presenting papulosquamous lesions or erythematous-squamous plaques of 3-5 mm in diameter, which are usually covered by fine scales and may coalesce to form plaques affecting the trunk and extremities. As the disease progresses, vesicles/pustules appear over the papules, which umbilicate and progress to hemorrhagic necrosis, with purpuric and crusty areas, which, if removed, reveal necrotic ulcers. Necrotic lesions heal in several weeks and leave a varioliform scar, sometimes accompanied by pruritus without any other symptoms2.

Acute lichenoid and varioliform pityriasis were first described in 1894 by Neisser and Jadassohn. Brocq, in 1902, classified it within parapsoriasis, calling it guttate parapsoriasis. In 1916, the acute variety was described by Mucha, which Habermann soon called PLEVA. Later, in 1966, a variant of PLEVA was described by Degos, which he called ulceronecrotic or hyperthermic3.

The histopathology of PLEVA is characterized by dermatitis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, accompanied by hemorrhage. Although the presence of lymphocytic vasculitis (LV) is known, the key finding in its characterization is fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls with a predominance of lymphocytic infiltrate; nevertheless, it has rarely been demonstrated4.

In this article, we present a clinical case of a patient with PLEVA, where histopathologically, we show the presence of LV, which has been rarely reported in the medical literature.

Reports on the racial and geographic predilection of all forms of pityriasis lichenoides (PL) are lacking. Due to its low frequency, its incidence is not well known, but it is estimated to occur in one out of every 2000 inhabitants. It is more frequent in young adults and children, with an average age of presentation of 5 to 10 years. It has a slight predominance in males, although some authors suggest a lack of accurate studies to support this finding5,6.

Due to the ease with which PL is frequently confused with other conditions, it is necessary to identify it correctly and recognize the varieties that exist using the current classification; by identifying its clinical manifestations, we can guide a diagnosis1.

Clinical case

We describe the case of a 5-year-old male from the state of Morelos with no important pathologic history. The patient consulted a physician in January 2021 for presenting lesions that were initially erythematous and later became hypopigmented lesions located on the trunk; they were diagnosed as scabies and were managed accordingly. Due to the persistence of the dermatosis, a skin biopsy was performed in the corresponding hospital unit. The biopsy showed histologic changes suggestive of mycosis fungoides (MF), so he was referred to our unit for a comprehensive evaluation. Physical examination revealed disseminated dermatosis on the trunk and extremities, consisting of multiple hypopigmented plaques, some with fine scales on their surface alternating with erythematous papular lesions of scaly appearance and others with central ulceration of varioliform appearance (Fig. 1A-E).

Figure 1 A: disseminated dermatosis characterized by hypochromic lesions and papules. B-D: close-ups of the lesions, note the polymorphism of the lesions showing erythematous papules, hypochromic plaques with scaling. E: lesions with central ulceration and necrotic crust giving a varioliform appearance.

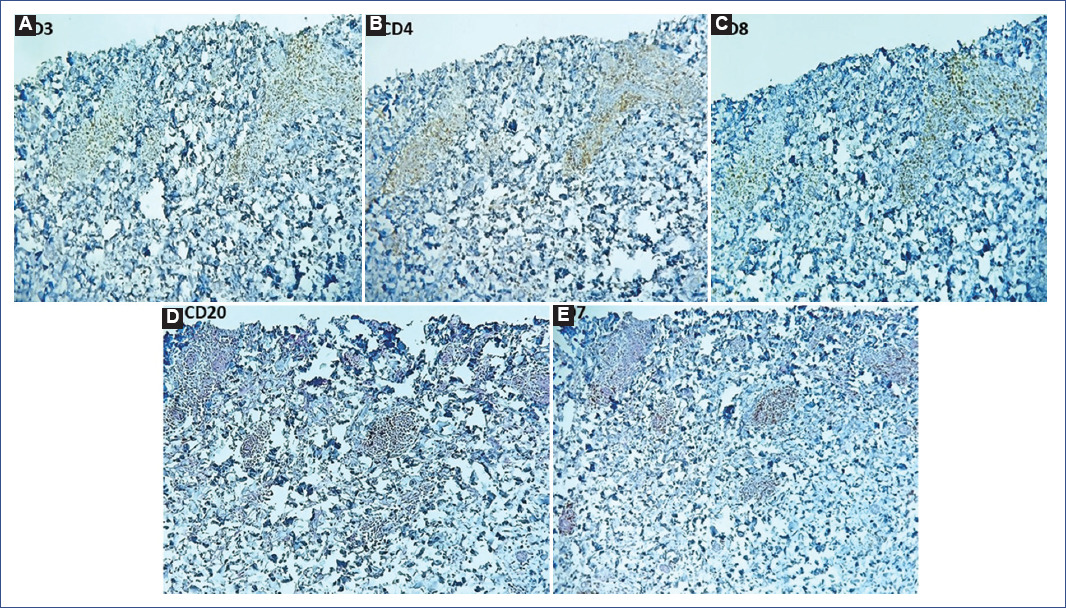

A slide review was performed, identifying a pattern associated with LV with focal epidermal necrosis (Fig. 2A-F). Immunohistochemistry (IMHQ) reported: CD3+, CD2+ weak, CD4+++, CD7 +++, CD8+, CD20 negative. Clinicopathologic correlation concluded the diagnosis of PLEVA (Fig. 3A-E).

Figure 2 A: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain 4x. Panoramic view identifying preservation of the epidermis with lymphocytic infiltrate with lichenoid distribution. B: H&E 10x. Close-up showing the presence of isolated exocytosis and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. C: H&E 10x. Note the lymphocytic vasculitis in the capillary vessel wall at the level of the mid dermis. D-F: H&E 40x. These images demonstrate true vasculitis with the presence of perivascular and invading infiltrate in the vessel wall, fibrinoid necrosis, erythrocyte extravasation, and karyorrhexis.

Figure 3 Immunohistochemistry (IMHQ) of vessels with vasculitis showed: A: CD3++, B: CD4+++, C: CD7 +++, D: CD8+ and E: CD20 negative.

Management was started with erythromycin 125 mg every 8 h for 21 days; magistral formula with 15% urea, 20% sunflower oil in cold cream every 6 h all over the body and 1% hydrocortisone cream, application every 12 h for 15 days, and then every 24 h for 15 days with suspension at the end of the scheme, applied in lesions of the abdomen and thighs. With this treatment, a decrease in papules and crust lesions was observed, achieving a partial improvement of the condition.

The patient had a relapse the following month, which motivated the initiation of treatment with PUVA-sol, adapted to our institution. This is formulated with a magistral formula with lime essence oil 40% in liquid petroleum jelly, to be applied at night on the compromised skin surface with morning cleansing and progressive sun exposure at 10 am starting with 10 min and gradually increasing until a tolerance of 30 min is achieved. The response to this management was toward 50% improvement of the papulosquamous lesions over 3 months; currently, residual hypochromic staining persists.

Discussion

PL is characterized by a disseminated dermatosis on the trunk and extremities. In this rash, desquamative papules are identified, and it has a centripetal distribution, although facial and mucosal involvement is rare. In general, the lesions are asymptomatic, and there is no extracutaneous involvement. However, it is possible to find pruritus, burning lesions, or fever when symptoms are present7. Depending on the speed of distribution, appearance, and duration of the lesions, three forms of PL have been classified: acute (PLEVA), chronic (PLC), and the febrile ulceronecrotic variant (FUMHD). The acute and chronic forms represent terminal groups of a continuous spectrum that includes intermediate stages and overlapping forms6,8.

The etiology of this entity is not yet well established; however, three recognized theories explain its presentation in outbreaks: (1) inflammatory reaction due to infectious agents, (2) inflammatory response secondary to T-cell dyscrasia, and (3) hypersensitivity vasculitis mediated by immunocomplexes5,6.

In the inflammatory reaction triggered by infectious agents, different pathogens associated with PLEVA, such as toxoplasma gondii, Epstein-Barr virus, Varicella-zoster virus, Parvovirus B19, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Mycoplasma, Cytomegalovirus, and HIV are recognized6.

The second theory, which attempts to explain an inflammatory response secondary to T-cell dyscrasia, indicates that PL is a disorder that may precede a T-cell MF arising from a monoclonal lymphocytic proliferation observed in the lesions6.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of T-cell receptor genes shows that in some cases of all three PL variants, dominant T-cell clonality is detected within their lesional lymphocytic infiltrates. Clonal T-cell-infiltrating FUMHD deserves special attention due to its destructive nature and neoplastic potential. In general, clonal FUMHD is histologically very similar to epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma and has a poor prognosis, thus perhaps representing a unique form of cutaneous CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. In contrast, in focal T lymphoma, cell clonality is not an absolute sign of underlying malignancy and may represent a benign condition with clonal T-cell proliferation. This condition is seen in cases of repeated exposure to superantigens and other skin disorders9,10.

The clinical picture of PLEVA is characterized by a sudden eruption consisting of erythematous papules of 3-5 mm in diameter, usually covered by fine scales that may coalesce and form plaques. As the disease progresses, vesicular pustules appear over the papules and umbilicate, progressing to hemorrhagic necrosis with purpuric and crusty lesions, which, when removed, reveal necrotic ulcers. These necrotic lesions heal in several weeks, leaving a varioliform scar11.

The histology of PLEVA will depend on the clinical form and stage. The most common histopathologic feature is the perivascular mononuclear lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, which primarily surrounds and involves the blood vessels of the superficial dermis8. The characteristic histopathologic findings of the PL types are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Histopathological characteristics

| Area | PLEVA | FUMHD | PLC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidermis | Focal and confluent parakeratosis, spongiosis, dyskeratosis, mild to moderate acanthosis, vacuolization of the basal layer with necrotic keratinocytes, occasional intraepidermal vesicles, focal epidermal necrosis; advanced findings: extension of the infiltrate in the epidermis, invasion of erythrocytes, generalized epidermal necrosis, nuclear debris in necrotic areas | Similar to PLEVA but with extensive necrosis | Focal parakeratosis, mild to moderate acanthosis, focal areas of spongiosis, minimal numbers of necrotic keratinocytes, minimal vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, focal invasion by a small number of lymphocytes and erythrocytes |

| Dermis | Edema; moderately dense lymphohistiocytic perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, often wedge-shaped and extensible, deep into the reticular dermis as well as diffusely obscuring the dermo-epidermal junction; extravasation of lymphocytes and erythrocytes with epidermal invasion; subepidermal vesicles in later lesions; dermal sclerosis in older lesions | Dense perivascular infiltrate, generally without atypia; otherwise similar to PLEVA | Mild superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic perivascular edema, infiltrate only focally obscuring the dermo-epidermal junction, occasionally extravasated erythrocytes |

| Vascular changes | Dilatation and engorgement of blood vessels in the papillary dermis with endothelial proliferation, vascular congestion, occlusion, dermal hemorrhage and erythrocyte extravasation | Similar to PLEVA vascular changes | Dilatation of superficial vessels, without invasion of vessel walls by inflammatory cells |

| Vasculitis | Invasion of vessel walls by inflammatory cells, rarely fibrin deposits inside vessel walls, very rare leukoplakia | Fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis | Not presented |

FUMHD: febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, PLC: pityriasis lichenoides chronica, PLEVA: pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Modified from Bowers and Warshaw5.

Particularly, PLEVA with the presence of LV was first reported in 1959. Marks et al. reported that approximately 25% of 102 biopsies of PL showed a degree of vascular damage with inflammation of the vascular endothelium. However, none of the reported cases showed histopathologic evidence of fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall11. Aydin and Gököz reviewed 127 cases of LV, where LP constituted 13% of the reported cases, the prototype being the lymphocytic lichenoid LV pattern. In addition, there is a study of 12 cases of PLEVA showing intense perivascular lymphocytic infiltration but no evidence of fibrinoid deposition, which concluded that PLEVA is not a true vasculitis12,13.

In the recent literature, there are no cases of LV in PLEVA in pediatric patients with fibrinoid necrosis confirmed by IMHQ, where the infiltrate cell type can be observed. The finding of fibrinoid necrosis within the vessel wall in confirmed cases of LV is essential to distinguish it from non-vascular inflammatory disorders with a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate13.

The Australian College of Dermatology reported the case of an adult patient with LV and PLEVA with IMHQ. This case showed severe angiocentric infiltrate of T lymphocytes and the absence of B-cells and neutrophils in the infiltrate of LV. The results may confirm and explain the role of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of vasculitis in PLEVA. The findings support the theory that lymphocytes are capable of damaging endothelial cells and other components of blood vessel walls14.

LV is a histopathologic finding in various and very heterogeneous dermatoses, such as connective tissue diseases, infections, lichenoid diseases, and drug reactions. However, LV is not well accepted by dermatopathologists as a pathologic mechanism because many inflammatory skin diseases present perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes and to apply the term LV to all these conditions would make it meaningless15.

Some authors state that LV can be defined as "a lymphocyte generally infiltrate perivascular space and located both superficial and deep, accompanied by fibrin in the wall or thrombi within the lumen of the venules." These authors consider it as a "mere epiphenomenon" secondary to a basic pathologic process and not in itself a fundamental pathologic process. While the different types of neutrophilic vasculitis have diagnostic significance for clinicians and histopathologists, LV has none. Arguments against the validity of LV as a meaningful concept include the lack of a disease, in which it is always found. In another article by Lee and collaborators, cases of LV are reported in patients with rickettsiosis and NK cell lymphoma without being demonstrated by IMHQ. In addition, there are case reports where LV has also been found in nodular scabies13,15.

Therefore, LV can be unequivocally inferred if there are lymphocyte infiltrates in and around the venules' walls, followed by fibrin deposition in their walls or vessels, or both. Diagnosis is problematic if there are no fibrin deposits. To separate such cases from the larger group of perivascular dermatitis, we can look for circumstantial evidence of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction directed against the vessel walls. This evidence may include lamination of the adventitia of venules in the form of concentrically arranged pericytes and basement membrane material, lymphocytic nuclear dust, or subendothelial or intramural infiltration of lymphocytes in arterioles. Supporting evidence of LV may include tissue necrosis from resultant ischemia. The walls of arterioles contain smooth muscle in layers thick enough to prevent diapedesis, so the finding of intramural inflammatory cells alone constitutes evidence of vasculitis15.

If these criteria are applied and looked for in biopsy specimens of inflammatory skin disease, LV will be found to be uncommon but not rare. All definitions have limitations, and one way ours may fail is the failure to recognize ultrastructural damage to small vessels as evidence of vasculitis15.

There are three forms of LV: the autodestructive form, which can be seen in lymphoproliferative disorders; lymphocytic endovasculitis, which occurs in thrombosis of obliterative processes; and the lichenoid form, which is seen in inflammatory skin diseases as part of the frequent features of lichenoid vascular change and erythrocyte extravasation16.

PLEVA has often been considered a LV, perhaps largely due to its clinical appearance. Often, the infiltrate has a wedge-shaped configuration if the sample includes most of a papule. In a small minority (perhaps 5%-10%) of cases, there is a true LV in Mucha-Habermann's disease. It is usually seen as a few tufts of fibrin in the mid or deep dermis vessel walls. In rare cases, large deposits may be present11,16.

We should consider that other conditions are present along with LV, such as MF, which represents a challenge for its early-stage diagnosis. PL-like MF is a rare subtype of MF that evolves with the characteristic lesions of PL, where the histopathologic findings of MF are epidermal infiltration by lymphoid cells, many with irregular shapes, discrete perivascular infiltrate in the superficial dermis, and numerous lymphocytes with slit nuclei, large atypical, and unclassifiable mononuclear cells. Infiltration of small veins in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat by atypical cells and fibrinoid necrosis of their walls are also detected17-20.

Historically, PLEVA has been confused with other dermatoses, some relatively benign and others potentially malignant. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, in which clinical conditions are differentiated in relation to the interpretation of the initial biopsy. The IMHQ shows a cellular infiltrate with a predominance of epidermal T-cells expressing the CD8 marker, in contrast to PLC, where these have a CD45 phenotype (Table 2).

Table 2 Differential diagnoses of clinical and histological PLEVA

| Clinical | Histological |

|---|---|

| Lymphomatoid papulosis (rare in infancy) | Pityriasis rosea |

| Chickenpox | Insect bites |

| Adverse drug reaction | Eczematous dermatitis |

| Varicelliform rashes due to HSV or enteroviruses | Neurotic excoriation |

| Varicelliform syphilis | Leukocytoclastic vasculitis |

| Leukocytoclastic vasculitis | Parapsoriasis gutata |

| Erythema multiforme | Erythroderma (exfoliative dermatitis) |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Secondary syphilis |

| Polymorphic light eruption | |

| Lymphomatoid papulosis |

HSV: herpes simplex virus, PLEVA: pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, Clinical differential diagnosis was obtained from Zegpi et al.3 Histological differential diagnosis was obtained from Hood and Mark4.

Various treatments have been used, which should be individualized according to the patient's clinical picture. For example, if a trigger (drugs, infections) is identified, the drug should be withdrawn, and the infection that triggered the condition should be treated21.

There are no standard guidelines for the treatment of PLEVA in children. According to the literature, suggested therapies include topical corticosteroids and immunomodulators, oral antibiotics, phototherapy, and systemic immunosuppressants. Immunomodulatory therapy with tacrolimus has shown adequate response. Simon et al. reported two patients with PLC with complete resolution of lesions using tacrolimus 0.03%, administered twice daily for 14 and 18 weeks22.

If the cause is an infectious agent, antibacterials are used, which have shown a good response. Among those used are tetracyclines, erythromycin, azithromycin, and dapsone, which have had acceptable results in some reports and case series. For example, a retrospective study of 24 children with PL treated with oral erythromycin, 30-50 mg/kg/day, showed a good response (> 50% improvement) in 64% of patients after 1 month of therapy, 73% after 2 months, and 83% after 3 months23.

In cases resistant to the previously mentioned therapies, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, and systemic corticosteroids may be used. The response is highly variable, depending on the severity of each condition23.

According to some authors, phototherapy is an effective therapeutic option, one of the first therapeutic lines. Among them, we find the psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) or the narrow-band UV-B phototherapy (NB-UVB) especially useful. The treatment consists of a combination of PUVA that causes a photochemical interaction through an oxygen-independent reaction producing the inhibition of deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and another oxygen-dependent reaction that induces apoptosis by free radicals. Psoralens are tricyclic furocoumarins, among which are methoxypsoralen (8-MOP), bergaptene (5-MOP), and trioxalene (3-MOP). MOP is the most widely used in Mexico22. Its action begins orally after 60 minutes; its levels are maximal after 2 h, and its elimination is total after 8 h. Topically, it initiates its action 20 min after application and remains active for approximately 30 min. Although its use is frequent in psoriasis and vitiligo, more than 20 skin conditions respond favorably to PUVA treatment. Unfortunately, the use of phototherapy in our country is limited by the scarcity of centers that offer it. An alternative to this limitation is administering psoralen, as indicated for PUVA, but using sunlight as the source of UVA radiation, known as PUVA-sun24-26.

In most children, PLEVA follows a benign self-limited course; however, relapses are common, and symptoms may be present for months or years. The duration of the disease ranges from 6 weeks to 31 months. Rare cases of PL progressing to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma have been documented. In 2002, Tomasini et al. reported a patient with a history of pityriasis since the age of 11 years who developed MF12,19,24.

PLEVA is often misdiagnosed with other more common diseases; therefore, it is important to know this condition to perform an adequate clinical-pathological-evolutionary correlation and implement the appropriate treatment. Furthermore, it is common to confuse it with other relevant conditions due to its poorer prognosis, such as MF. In the pediatric population, its prevalence is infrequent, hence the importance of presenting this case, where in addition to presenting as a LV, it was confirmed by IMHQ.

In general, LV is a poorly sustained histopathologic pattern frequently found in multiple conditions. According to the literature, there are few reports of actual LV within the histopathologic findings of PLEVA, which, in our case, could have an impact on the time course of cutaneous inflammatory activity. Since the finding of LV is unusual, we propose an intentional search in serial sections on papular-necrotic lesions for these changes, mainly in those patients with persistent dermatosis.

In conclusion, we do not know whether LV in PLEVA is a common event or has been missed until now. In the scenario in which cases with this finding present a different evolution, as this particular case could be, questions will arise that will be resolved in subsequent reports. A long-term follow-up will allow to establish its presence with a better therapeutic decision.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)