Introduction

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is characterized by an immune dysregulation secondary to macrophage and lymphocyte proliferation leading to systemic hyperinflammation1. MAS associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is rare. Fukaya et al. reported 18 patients with hemophagocytic syndrome and SLE among 350 patients admitted with SLE to a hospital in Japan between 1997 to 2007 (a study population-specific frequency of 5%)2.

Multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with SARS-CoV-2 is a recently described entity3. Rigorous use of clinical criteria for MIS-C without considering it a dynamic, evolving entity with imprecise limits could lead to diagnostic errors. Regardless of a consensus international definition, it is necessary to apply medical reasoning in managing these patients. Given that MIS-C presents with specific signs and symptoms and different clinical presentations4, we report this case to describe the association between MAS and SLE in a male pediatric patient initially diagnosed with MIS-C due to overlapping clinical features.

Clinical case

We describe the case of a previously healthy 11-year-old Hispanic male from Lima, Peru, who was admitted to the pediatric emergency department with a history of skin erythema, general discomfort, headache, and arthralgias with a duration of one week. One day before admission, he presented with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever. RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) for SARS-CoV-2 was negative; however, two months earlier, the mother was positive for COVID-19.

Oxygen saturation was 98%, heart rate 110 bpm, temperature 37.6°C, respiratory rate 20 rpm, blood pressure 106/70 mmHg, weight 57 kg, and he showed a facial expression consistent with pain. On physical examination, he had an erythematous rash on the anterior region of the right chest and the palms of the hands, hip arthralgia, and chest pain over the ribs on palpation. Bilateral cutaneous findings are shown in Figure 1. The patient presented with diffuse abdomen tender to palpation, McBurney (+), fever, and decreased joint mobility ranges in arms and legs due to pain. Laboratory test results showed inflammatory markers including leukocytosis, lymphopenia, and elevated C-reactive protein levels, d-dimer, elevated pro-B natriuretic peptide, ferritin, and fibrinogen.

With the diagnosis of MIS-C, the patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (2 g/kg/dose), acetylsalicylic acid (50 mg/kg/day), and methylprednisolone acetate (2 mg/kg/day). Upon clinical and inflammatory marker improvement, he was discharged. However, on the ninth day since the initial presentation, he was readmitted with a similar clinical picture, fever, and elevated inflammatory markers. Therefore, the admission diagnosis was refractory MIS-C associated with suspected sepsis. Extensive empirical treatment of antibiotic coverage and a second dose of immunoglobulin and corticosteroids was started. An echocardiography study showed normal coronary arteries, a patent foramen ovale (1.6 mm), mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, no signs of pulmonary hypertension, and no pericardial effusion. An abdominal CT scan showed hepatosplenomegaly, and a chest X-ray demonstrated bilateral pulmonary consolidation. Forty-eight hours after initiating treatment, fever persisted, and a diffuse exanthema was observed. Inflammatory markers were elevated, including interleukin-6 (Table 1). The third cycle of immunoglobulin with corticosteroid pulse was administered, and prophylactic anticoagulation was ordered. The list of differential diagnoses was reviewed, and it was decided to extend the study to infectious, hemato-oncologic, and rheumatologic causes.

Table 1 Evolution of paraclinical results during hospitalization

| Laboratory | Reference range | Days of hospitalization | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 22 | 37 | 39 | 48 | 59 | ||

| Leukocytes (x103/µL) | 5.0-14.5 | 20.26 | 11.30 | 25.76 | 21.63 | 16.28 | 11.45 | 9.07 | 2.45 | 5.29 | 11.01 | 8.61 |

| Neutrophils (x103/µL) | 1.8-8.0 | 17.91 | 8.60 | 24.12 | 19.65 | 14.11 | 9.02 | 6.4 | 0.78 | 2.70 | 6.09 | 4.04 |

| Lymphocytes (x103/µL) | 0.9-5.2 | 1.10 | 1.69 | 1.05 | 1.29 | 0.98 | 1.55 | 1.98 | 1.05 | 1.38 | 3.73 | 4.13 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.5-15.5 | 12.7 | 12 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 12 | 11.1 | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| Platelets (x103/µL) | 150-400 | 318 | 309 | 382 | 405 | 309 | 229 | 79 | 195 | 132 | 393 | 517 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 22-55 | 30 | 32.1 | 21.4 | 27.8 | 21.4 | 15 | 25.7 | — | 19.3 | 21.4 | 44.9 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.3-0.7 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.36 | — | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.58 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.2-4.8 | 4.38 | 3.66 | 3.42 | 3.23 | 2.78 | 2.86 | 3.09 | 4.17 | 3.44 | 3.42 | 4.95 |

| LDH (U/L) | 120-246 | 297 | 304 | — | — | 368 | 723 | 2760 | 671 | 665 | 582 | 291 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | <200 | — | — | 109 | — | 76 | 102 | 104 | — | — | 164 | 254 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | <250 | — | — | 117 | — | 93 | 102 | 313 | — | — | 316 | 275 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 28-365 | 1409 | — | 5985 | 8592 | — | 32473 | 75706 | — | — | 5776 | 1949 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0-1.0 | 23.7 | 12.7 | 10.8 | 13.4 | 17.3 | 11.4 | 8.4 | — | 10.8 | 3.7 | — |

| GOT (U/L) | 10-35 | 29 | 43 | 43 | 40 | 62 | 76 | 651 | 153 | 141 | 125 | 64 |

| GPT (U/L) | 10-49 | 34 | 30 | 48 | 37 | 44 | 37 | 424 | 189 | 191 | 159 | 148 |

| CPK (U/L) | 34-145 | 23 | — | 18 | — | — | 23 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CPK-MB (ng/mL) | 0-6 | — | 0.3 | — | < 0.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pro-BNP (pg/mL) | 0-125 | 9.3 | 278.1 | — | — | — | — | 158 | — | — | — | — |

| Troponins (ng/mL) | 0-0.01 | < 0.003 | < 0.003 | — | 0.005 | — | — | < 0.003 | — | — | — | — |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 200-400 | 632.04 | 468.9 | 521.02 | 420.49 | 371.4 | 342.07 | 201.62 | — | 422.69 | 453.45 | 561.2 |

| D-dimer (ug/mL) | 0-0.54 | 5.23 | — | 1.7 | 4.3 | 22.95 | 16.41 | 29.37 | — | 6.45 | — | — |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 0-2.0 | — | — | — | 77.2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

BNP, B-natriuretic peptide; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; CPK-MB, creatine phosphokinase myocardial band; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT, glutamic pyruvic transaminase; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

On day 22 of admission, the patient remained febrile; laboratory results revealed a quantitative increase of inflammatory markers, worsening anemia, worsening thrombocytopenia, severe hyperferritinemia, severe transaminitis, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypocomplementemia (C3 and C4) (Table 1). We performed a bone marrow aspirate, which showed granulocytes and platelet hemophagocytosis with the presence of histiocytes. A positive antinuclear antibody with a speckled nucleated pattern was obtained in titer 1/320: autoantibodies against positive Ro52 recombinant antigens and positive lupus anticoagulant. The infectious study revealed positive serology for Bartonella henselae. Given the diagnosis of MAS due to SLE, a chemotherapy treatment protocol was initiated, including etoposide, cyclosporine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate. The patient presented complications secondary to chemotherapy (febrile neutropenia, severe pancytopenia) and received broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, including Bartonella therapy and antifungal treatment. As we observed a good clinical response to treatment and normal paraclinical tests, home discharge and outpatient follow-up was indicated.

Discussion

The new presenting condition secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children is MIS-C3. Its early recognition for pediatricians could be challenging, and the appropriate indication of therapeutic options is still under debate. There may be a high bias in MIS-C diagnosis during the pandemic, also considering that diagnostic definitions are broad.

Here, we report a case with a problematic diagnostic pathway due to a presentation similar to MIS-C, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). Several diseases may present with similar clinical manifestations, so we may currently overestimate the diagnosis of MIS-C in the pediatric population. Similarly, the use of empiric therapy without a definitive diagnosis and the cost-benefit should be evaluated. MIS-C is a syndrome and a new pathologic entity with a solid epidemiologic correlation. It is a primary diagnosis in any patient with clinical presentation, as in this case, but it is not always the presenting disease.

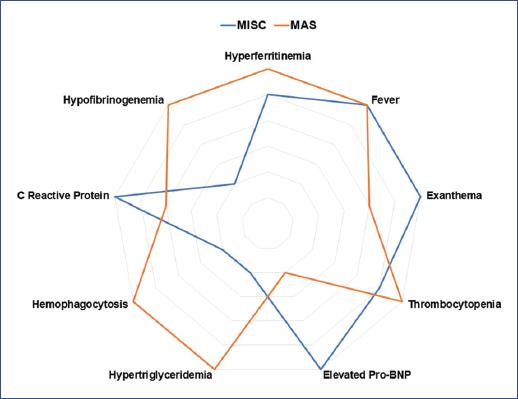

The sequelae and mortality of pediatric SLE are associated with several risk factors: age at early diagnosis, male sex, and non-Caucasian race (African American, Asian, and Hispanic). Most children present with fever, arthralgia, arthritis, rash, myalgia, fatigue, and weight loss. These symptoms are quite nonspecific, so the patient must meet the diagnostic criteria determined by the American College of Rheumatology, as described in this case5. Gracia-Ramos presented a review of cases linking lupus erythematosus and SARS-CoV-2. However, the presentation of MAS mimicking MIS-C in a pediatric patient has not been described, thus presenting different challenges6. A difference of presentation between MIS-C and MAS can be observed in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Differential diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). BNP, B-natriuretic peptide.

MAS falls within the “cytokine storm syndrome” spectrum and is characterized by low blood cell count (cytopenia) and multiorgan failure, involving the lung, liver, kidney, and heart1. In addition to elevated serum cytokines, elevated ferritin concentrations are characteristic of this syndrome. Macrophages expressing CD163 are the source of ferritin; in this sense, elevated serum ferritin is also a biomarker of poor prognosis1.

In the case of negative RT-PCR and serology for SARS-CoV-2 and high clinical suspicion of MIS-C, repeat serology is recommended 3-4 weeks after admission. It has been described that 26-55% of patients with MIS-C have positive RT-PCR and up to 90% positive IgG serology7,8. The broad diagnosis that mentions a positive contact as a diagnostic criterion can be misleading.

MAS-associated SLE is rare. Children with rheumatologic conditions such as SLE and Kawasaki disease are also at risk for MAS1. Borgia et al. reported 9% of patients with SLE and MAS in a cohort of children in Canada9. In this study, most patients with MAS were female, and the mean age at diagnosis of SLE was 13 years9. MAS is primarily described in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) but can occur in different rheumatologic diseases. Bennett et al. described 121 patients with MAS; only 19 pediatric patients had MAS secondary to SLE10. The case described here falls into this reduced group of patients. In the previously mentioned study, patients with SLE presented similar mortality but required more ICU care, more mechanical ventilation, and higher vasopressor support10.

Our patient was diagnosed with MAS secondary to SLE. Delayed treatment of this condition could have been life-threatening and could have progressed into multiorgan failure. Treatment of secondary MAS is directed at the underlying condition1. Gupta et al. reported a case of a 15-year-old female patient with MAS secondary to SLE who received methylprednisolone pulses and oral cyclosporine with a good response to treatment11. This report was similar to another case in a 22-year-old male treated with methylprednisolone pulses and azathioprine12. Similar to previous reports, our patient had an adequate evolution with the proposed treatment for this disease13. In addition, the patient was managed by a multidisciplinary group including oncology and rheumatology, with a hybrid therapy scheme for HLH and MAS.

The coexistence of SLE and MAS has overlapping clinical features, so a high level of suspicion is necessary for diagnosis. Rapid initiation of treatment of MAS is of extreme importance, as it is a potentially fatal and rapidly progressive condition, even with adequate treatment.

In conclusion, MAS-associated SLE is rare. Identification of differential etiologic diagnoses that share MIS-C criteria is critical to avoid delays in therapies. MIS-C refractory to treatment should raise suspicion of other etiologies such as MAS, which can be fatal if a definitive diagnosis is not reached.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)