Introduction

Since late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global public health threat1, and in March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic.

A recently published case series from China suggests that young children, especially those < 1 year of age, could more likely experience severe outcomes such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure2.

Several publications have described clinical and laboratory features of critically ill adult patients. However, our understanding of the clinical spectrum of pediatric cases and their treatment remains incomplete because very few critically ill pediatric cases with this disease have been reported.3,4

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) as a syndrome in an individual < 21 years of age that includes fever, laboratory evidence of inflammation, and evidence of clinically severe illness that requires hospitalization with multisystem involvement (cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermatologic, or neurologic), at least in two organs. Moreover, no alternative diagnoses are possible, but these children are positive for current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection (confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (PCR), serology, or antigen testing) or have been exposed to COVID-19 within 4 weeks before symptom onset.5

This report describes the clinical course and treatment of a critically ill infant with COVID-19 presenting features of MIS-C.

Case report

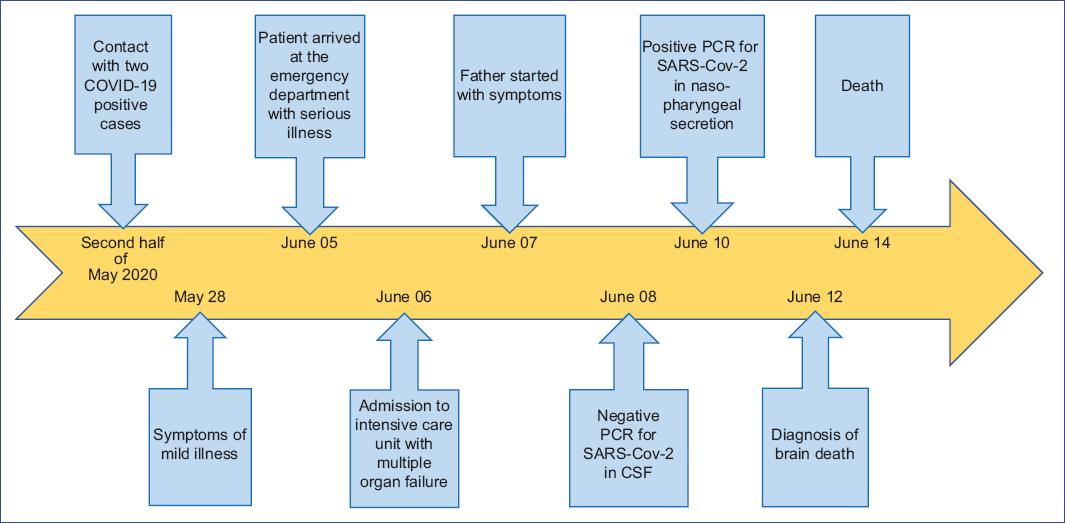

We describe the case of a 9-month-old male infant from Xonacatlán, State of Mexico, son of a 28-year-old healthy mother and a 25-year-old father out of the family nucleus. The patient was born at 38 weeks of gestation with no perinatal complications and received breastfeeding for one month. Subsequently, the infant started with formula and complementary feeding from 6 months of age. The psychomotor development was normal for the age. The vaccination schedule was incomplete: the infant only had one dose of each vaccine, rotavirus and influenza. The patient lived in an urban-type house with separated parents from the beginning of the pregnancy. However, the patient began living with the father during the second half of May 2020. The father had a relative who died from COVID-19 and two positive contacts for COVID-19, with whom he spent 2 weeks before the onset of the patient's symptoms. Moreover, the child's father began with symptoms that included odynophagia, unquantified fever, general malaise, and a sensation of chest tightness on June 7, 2020. However, no diagnostic test was performed for COVID-19.

The patient began his current condition on May 28, 2020, with intermittent irritability, non-quantified fever, catarrhal syndrome, and semi-liquid diarrheal stools 2 to 3 times in 24 hours. However, medical attention was not sought, and it was unknown whether the fever remitted or not since it was not quantified again. On June 5, 2020, the patient presented intermittent fever quantified up to 40°C, irritability, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures. In the health unit, antipyretics were administered, and the infant was referred to the emergency department. The patient was admitted to the hospital with fever and seizures lasting over 40 minutes without regaining consciousness. Therefore, the treatment for status epilepticus started. Then, the patient was sent to the pediatric intensive care unit with a diagnosis of neuronal infection, where non-invasive ventilation was provided.

Vital signs upon admission were the following: heart rate, 180 bpm; respiratory rate, 60 rpm; blood pressure (BP), 120/80 mmHg; mean BP, 106 mmHg; temperature, 38°C; weight, 7.8 kg; height, 70 cm.

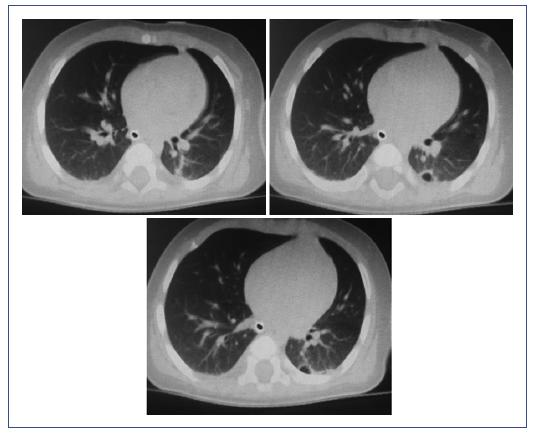

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit on June 6, 2020, in a state of septic shock with high resistance, respiratory failure, and spastic quadriparesis. A rapid sequence of intubation with a modified technique was performed to manage the patient's airway with probable COVID-19 diagnosis based on the medical history. During laryngoscopy, white plaques and purulent membranes were observed. Crystalloid therapy and aminergic management with norepinephrine and dobutamine were administered, with a partial response but persistent poor tissue perfusion, hyperdynamic state, respiratory failure, bilateral crackles, isolated wheezing without hypoventilation zones. The patient was isolated in a section for patients with COVID-19. Blood cultures, general laboratory studies, chest (Figure 1) and head (Figure 2) computed tomography (CT) scans, lumbar puncture (without difficulty), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal secretion and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were performed (Table 1).

Table 1 Laboratory test results

| Complete metabolic panel (07/06/2020) | Coagulation panel (07/06/2020) | Complete blood count (07/06/2020) | Arterial gasometry (07/06/2020) | Cerebrospinal fluid (07/06/2020) | Specials | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 120 mg/dL | D-dimer | 1314 ng/mL | Hb | 10.4 g/dL | pH | 7.35 | Xanthochromic | PCR SARS-Cov-2 in CSF (08/06/20) | Neg | |

| Cr | 0.45 mg/dL | PT | 22.9 s | Hto | 32% | PCO2 | 30 mmHg | Leukocytes | 3 mm3 | ||

| Urea | 4 mg/dL | PTT | 51.9 s | Leukocytes | 19300 /µL | PO2 | 48 mmHg | Erythrocytes | 1215 mm3 | ||

| Na | 150 mEq/L | Lymphocytes | 26% | HCO3 | 16.6 mmol/L | Microproteins | 79.5 mg/dL | ||||

| K | 2.6 mEq/L | Neutrophils | 67.4% | SO2 | 81% | Glucose | 109 mg/dL | ||||

| Albumin | 3.2 g/dL | Platelets | 277000 /mm3 | BD | -9.0 mmol/L | LDH | 287 U/L | PCR SARS-Cov-2 naso- pharyngeal (10/06/20) | Pos | ||

| AST | 297 U/L | Culture | Negative | ||||||||

| ALT | 104 U/L | ||||||||||

| LDH | 1228 U/L | ||||||||||

| CPK | 9913 U/L | ||||||||||

| CK-MB | 362 U/L | ||||||||||

| Blood culture (13/06/20) | Neg | ||||||||||

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BD, base deficit; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; Cr, creatinine;

Hb, hemoglobin; HCO3, bicarbonate; Hto, hematocrit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Neg, negative; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen; Pos, positive; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; SO2, oxygen saturation.

The pharmacological treatment indicated included double antibiotic coverage with ceftriaxone and vancomycin due to suspected bacterial meningitis; oseltamivir (3 mg/kg every 12 hours) for incomplete vaccination schedule against influenza; lopinavir/ritonavir (100 mg/25 mg every 12 hours) due to progressive deterioration at the pulmonary level; ivermectin (200 mg/kg every 12 hours), methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day, suspended on day 4), human immunoglobulin (1 g/kg/day), and enoxaparin (1 mg/kg every 12 hours); sedation with benzodiazepine and hypnotic analgesia, as well as anticonvulsant management based on phenytoin and levetiracetam.

The patient presented an unfavorable evolution with multiple organ failure refractory to treatment and severe neurological compromise. Brain death was documented on day 5 of stay, and irreversible cardiorespiratory arrest on June 14, 2020 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Since severe cases of COVID-19 in pediatric patients are unusual, little is known about the clinical course and treatment of this age group.

At admission, the patient was diagnosed with a neurological infection and septic shock as a complication and showed solid clinical evidence of bacterial superinfection despite negative cultures. However, when integrating the different existing variables, a multiorgan compromise was concluded. When associated with the family history collected in the clinical record, the multiorgan compromise immediately suggested a multisystemic inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19. The various etiologies of the multiorgan involvement in this critically ill pediatric patient cannot be completely differentiated. However, as we cannot disregard the clinical manifestations, the tomographic findings, and the positive test for COVID-19 as a demonstrable cause of this condition, we considered it sufficient evidence to be reported as MIS-C.

Initially, the patient manifested typical COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever and general malaise, and other non-specific symptoms such as rhinorrhea and diarrhea6,7. In this initial stage of the disease, the patient showed mild symptoms but developed symptoms compatible with a neurological infection later, reaching a state of shock and multisystemic failure that led to death (a critical case)2.

Nervous system involvement has been described in adults. Although it is non-specific in most cases, sometimes the virus has been isolated, and little is known about these cases. In this patient, the first manifestation of severe disease was the meningeal syndrome. PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 were negative in the CSF; although there is evidence of neurotropism of this virus and, in some cases, it has been isolated, this depends mainly on the viral load. It is also true that nervous system involvement may occur at a second stage when the immune system initiates its response and the SARS-CoV-2 viral load is reduced. At this stage, a severe hyperinflammatory systemic reaction, known as a cytokine storm, has been observed in some cases. Probably, this reaction occurred in our patient affecting several organs and systems8,9.

The patient progressed to multiorgan failure, brain death, and ultimately death. Since the pediatric intensive care unit admission, this patient met the diagnostic criteria of a multisystemic inflammatory syndrome related to COVID-19: fever, laboratory evidence (leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis, elevated D-dimer, coagulopathy), evidence of multisystemic involvement (status epilepticus, shock, hepatitis, coagulopathy, anemia), and positive PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal secretion. Although this last criterion was not present initially, the diagnostic suspicion related to COVID-19 was established immediately due to the history of contact with people who presented symptoms and virus isolation 2 weeks earlier. Thus, there were no alternative diagnoses or etiologies. Also, no previous comorbidities or immunocompromise were documented in this patient5,10. The status epilepticus could be explained as a consequence of inflammation in the central nervous system; another possible etiology could be a massive cerebral infarction due to the COVID-19 associated coagulopathy, also observed in our patient4,9,10.

Regarding treatment, intensive hemodynamic and neurological management, and considering the suspected etiology, we tried to cover most of the recommendations provided in the literature, although no consensus exists on the management of critically ill pediatric patients. From the beginning, we used antiviral drugs to reduce the viral load: lopinavir, ritonavir, oseltamivir11,12. In this regard, oseltamivir was used not as therapy directed to COVID-19 but to cover the possibility of coinfection by the influenza virus since the patient did not have a complete vaccination schedule for this disease. Lopinavir and ritonavir were administered as compassionate drug use since there is no evidence to support their efficacy in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection. Also, ivermectin was prescribed as a compassionate drug use given the reports of its antiviral activity in vitro13.

Broad-spectrum antimicrobials were used to cover a possible concomitant bacterial neurological infection, a frequently reported finding12,14,15. In the present case, this bacterial infection was suspected based on the laryngoscopic findings. Blood and CSF cultures were negative. As a pharyngeal exudate was not possible to perform due to the patient's severity and condition, no bacterial infection could be documented.

Steroids and human immunoglobulin were used as immunosuppressants to decrease the likely exaggerated immune response and cytokine storm reported in the pathophysiology of COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome8,12,16.

We should clarify that the evidence of the safety and efficacy of methylprednisolone, human immunoglobulin, ivermectin, lopinavir, and ritonavir in the context of COVID-19 is still insufficient. The compassionate use of these drugs was made, given our patient's presentation and critical condition. However, it is essential to individualize cases and conduct more clinical trials in the context of this severe pandemic.

It should be noted that the treatment course may have been different considering some critical factors. Firstly, the evolution of approximately 10 days and symptomatic importance were underestimated; secondly, the history of contact with people infected with SARS-CoV-2 was minimized; finally, the multiorgan compromise at admission was not addressed, possibly because of the distraction represented by the neurological involvement. Therefore, it is important not to minimize any history in the anamnesis or signs present at the physical examination, especially in patients < 1 year of age, since it may represent delays in the diagnostic approach and treatments.

Given that the presentation of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in young children is variable and still no defined criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of this group of patients exists, it was essential to document a severe form of COVID-19 presentation in a child < 1 year of age. This report may generate future research hypotheses, motivate more clinicians and researchers to publish these presentations, and lay the groundwork for national or regional diagnostic criteria and therapeutic guidelines to improve outcomes in this group of infant patients.

Based on the observations from this case, our recommendation is to perform a thorough clinical history, without minimizing data, a thorough physical examination and consideration of SARS-CoV-2 infection in all pediatric patients, especially those < 1 year of age, with severe or complicated disease and multiorgan involvement on admission to the hospital.

It is important to report all cases of severe disease due to COVID-19 in this age group. This information will allow us to recognize the clinical presentation from admission and develop a diagnostic and therapeutic consensus for critically ill infants with suspected COVID-19 infection.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)