Introduction

In December 2019, several cases of pneumonia of unknown origin emerged in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Most of the patients reported exposure to the Wholesale Seafood Market in Huanan, which sold live animal species1. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned that the outbreak of a new coronavirus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (which causes coronavirus disease [COVID]-19 disease), was highly virulent and caused respiratory illness2. Most cases were reported from China and were exported to other countries, spreading the contagion and reaching pandemic proportions in February 20203.

Coronaviruses get their name from the distinguishing viral particles (virions) that crown their surface. This family of viruses infects a wide range of vertebrates, especially mammals and birds, and is considered the leading cause of viral respiratory infections worldwide. The incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 extends to 14 days, with an average time of 4-5 days from exposure to the onset of symptoms4. Atypical presentations have been described in older adults; delay in the onset of fever and respiratory symptoms is sometimes observed in people with other comorbidities. Fever has been found in 89% of patients during their hospitalization, as well as headache, confusion, rhinorrhea, sore throat, hemoptysis, vomiting, and diarrhea (less common < 10%). Several studies have reported that the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 in children are similar to those in adults but milder5. The clinical picture varies from a mild upper respiratory airway condition to severe pneumonia with sepsis. In infants with SARS-CoV-2 infection, fever, lethargy, rhinorrhea, cough, tachypnea, increased breathing effort, vomiting, diarrhea, and feeding intolerance or decreased intake have been detected, which may be confused with other pathologies, given the non-specificity of the symptoms5.

Because asymptomatic individuals are not routinely tested, the prevalence of asymptomatic infection and the detection of pre-symptomatic infection are not well known. Up to 13% of patients with positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were found to be asymptomatic. The exact degree of SARS-CoV-2 viral ribonucleic acid that confers transmission risk is not yet precise. The risk of transmission is thought to be higher when patients have symptoms since viral shedding is higher at the onset of symptoms and decreases over several days to weeks6.

Despite the global spread, the epidemiological and clinical patterns of COVID-19 remain unclear, particularly among children. The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in children are generally reported to be less severe and less frequent than in adult patients3. In Mexico, the first documented case was in the last week of February, and the cessation of school and work activities for confinement purposes to prevent the spread was issued in March. In this phase (with a high spread of cases and during the Jornada Nacional de Sana Distancia program), the health system was modified, and the so-called COVID centers were created, which organized all their structure for the care of infected patients7. Therefore, the objective of this study was to describe the profile of patients under 18 years of age treated at a pediatric COVID center and its association with test confirmation, endotracheal intubation, and death.

Methods

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in the emergency department of a COVID pediatric reference hospital in Mexico City from March to June 2020. Patients under 18 years of age who came for a consultation with a clinical picture compatible with SARS-CoV-2 (fever, respiratory symptoms, or general malaise) and who underwent RT-PCR testing were included in the study. Those with unreported test results or samples referred to as insufficient or poorly taken were excluded from the study.

Patients were initially classified in a specific area where general data, primary symptoms, and comorbidities were registered and explored.

Recorded clinical data were fever (> 38°C sustained for 1 h or 38.3°C at any time), cough, odynophagia, dyspnea, diarrhea, acute general malaise (in < 24 h), rhinorrhea, polypnea (according to age), vomiting, conjunctivitis, and cyanosis. Moreover, in children < 2 years of age, the presence of irritability was interrogated, and in children > 5 years of age, the presence of headache, chest pain, myalgias, arthralgias, and abdominal pain was examined.

Based on the physical examination and vital signs, a severe condition was defined by the presence of rales, alterations in the state of consciousness, tachypnea, tachycardia, fever, and desaturation of < 90% (measured with pulse oximetry).

According to age, the patients were classified as infants (< 2 years), preschoolers (2.1-6 years), schoolchildren (6.1-12 years), and adolescents (over 12.1 years).

Samples were obtained by nasopharyngeal swab and analyzed in laboratories authorized by the Secretaría de Salud (Mexican Ministry of Health).

Pre-existing comorbidities were recorded in the following categories: cancer (any hemato-oncological neoplasm under treatment), neurological disorders (conditions with malformations, epilepsy or developmental disorders that result in intellectual disability), congenital heart diseases (repaired or non-repaired), autoimmune diseases (specifically systemic lupus erythematosus disease, juvenile, or rheumatoid arthritis), allergic (asthma, atopic dermatitis, and cows milk protein allergy), intestinal surgery (intestinal atresia of any degree or pancreatitis), infectious (specifically: acquired immunodeficiency virus), syndromic (spectrum of diseases conditioned by chromosomal alterations of Mendelian transmission, trisomies, or chromosomal deletions), renal (chronic kidney disease from any cause or a kidney transplant), pulmonary (pulmonary hypertension of WHO Groups III, IV, and V; cystic fibrosis and lung malformations), endocrinology (hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and panhypopituitarism), and obesity.

The outcomes recorded were home surveillance, hospitalization (including intensive care areas), need for assisted mechanical ventilation, and death.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were expressed in frequencies and percentages, age in median, and interquartile ranges. A comparative analysis was performed between positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 subjects with a χ2 test. Furthermore, the proportion of symptoms presentation according to pediatric stages was compared with the linear χ2 test. The risk was estimated with bivariate odds ratio (OR) analysis according to the symptoms associated with a positive test and required ventilatory mechanical support. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical program used was SPSS version 20 for MAC from IBM®.

Results

During the study time frame, 540 tests were taken (30 were discarded due to poor technique or insufficient sample), and 510 patients were included, with a median age of 5 (1.3-11) years; 270 (53%) were male. According to age groups, the distribution was as follows: infants, 148 (29%); preschoolers, 134 (26.7%); schoolchildren, 104 (20.4%), and adolescents, 122 (24%). Infants and adolescents were the most frequently infected groups (32.5% for both). When comparing subjects with and with no SARS-CoV-2 infection, the only variable that showed statistical differences was the history of contact with a positive case (27.6% vs. 57.9%). The remaining variables are shown in table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of pediatric patients with and with no SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Total | No SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 431 | 79 | |||||

| 510 | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

| Age (years) | 5 (1.3-11) | 5 | 1.4-11 | 4.9 | 1.2-13 | 0.9 |

| Gender | 0.2 | |||||

| Male | 270 | 223 | 51.7 | 47 | 59.5 | |

| Female | 240 | 208 | 48.3 | 32 | 40.5 | |

| Age group | 0.1 | |||||

| < 2 years | 148 | 123 | 28.5 | 25 | 32.5 | |

| Preschoolers | 134 | 118 | 27.4 | 16 | 20.8 | |

| Schoolchildren | 104 | 93 | 21.6 | 11 | 14.3 | |

| Adolescents | 122 | 97 | 22.5 | 25 | 32.5 | |

| Origin | ||||||

| Mexico City | 195 | 164 | 38.1 | 31 | 39.2 | |

| State of Mexico | 218 | 185 | 42.9 | 33 | 41.8 | |

| Other | 97 | 82 | 19.0 | 15 | 19.0 | |

| Influenza vaccine | 119 | 96 | 23.3 | 23 | 29.5 | 0.6 |

| Contact | 160 | 116 | 27.6 | 44 | 57.9 | 0.001 |

| Intubated | 44 | 33 | 12.3 | 11 | 19.3 | 0.5 |

| Comorbidities | 231 | 185 | 42.9 | 46 | 58.2 | 0.06 |

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

*MannWhitneys U-test; linear χ2 test.

A comparative analysis between subjects with and with no SARS-CoV-2 infection and their comorbidities was performed; no statistically significant differences were found (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of comorbidities between patients with and with no SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Type of comorbidity | Total | No SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 231 | n = 185 | n = 46 | ||||

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Cancer | 77 | 33.3 | 60 | 32.4 | 17 | 37 |

| Neurological | 23 | 10 | 19 | 10.3 | 4 | 8.7 |

| Congenital heart disease | 32 | 13.9 | 27 | 14.6 | 5 | 10.9 |

| Autoimmune | 12 | 5.2 | 11 | 5.9 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Allergic | 15 | 6.5 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Surgical | 12 | 5.2 | 9 | 4.9 | 3 | 6.5 |

| Infectious | 8 | 3.5 | 6 | 3.2 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Syndromic | 11 | 4.8 | 9 | 4.9 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Kidney | 15 | 6.5 | 11 | 5.9 | 4 | 8.7 |

| Pulmonary | 11 | 4.8 | 10 | 5.4 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Endocrinological | 6 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.7 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Obesity | 9 | 3.9 | 5 | 2.7 | 4 | 8.7 |

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.χ2 test, no statistically significant differences were found.

The difference in the presentation of symptoms between subjects with and with no the infection showed that the variables with p < 0.05 value were chest pain (6% vs. 14%), general malaise (33 vs. 44%), and sudden onset of symptoms (63% vs. 75%). These three variables also showed statistically significant OR values. When comparing the presentation of symptoms between age groups in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that presented differences were dyspnea, irritability, shivers, myalgias, arthralgias, general malaise, and abdominal pain (Table 3).

Table 3 Differences in the presentation of symptoms in patients with and with no positive test for SARS-CoV-2

| Symptoms | Total | No SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | p* | OR (95% CI) | Neonates | Preschoolers | Schoolchildren | Adolescents | p** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25 | n = 16 | n = 11 | n = 25 | |||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Fever | 313 | 266 | 62 | 47 | 60 | 0.6 | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | 12 | 48 | 12 | 75 | 7 | 64 | 16 | 64 | 0.2 |

| Cough | 210 | 171 | 40 | 39 | 49 | 0.1 | 1.4 (0.9-2.3) | 13 | 52 | 6 | 38 | 8 | 73 | 12 | 48 | 0.3 |

| Odynophagia | 96 | 82 | 21 | 14 | 19 | 0.6 | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | NA | 4 | 25 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 36 | 0.3 | |

| Dyspnea | 145 | 117 | 28 | 28 | 35 | 0.1 | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 7 | 28 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 64 | 12 | 48 | 0.008 |

| Irritability | 180 | 154 | 36 | 26 | 33 | 0.6 | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 13 | 52 | 7 | 44 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 20 | 0.01 |

| Diarrhea | 100 | 83 | 19 | 17 | 22 | 0.6 | 1.1 (0.6-2) | 4 | 16 | 5 | 31 | 2 | 18 | 6 | 24 | 0.07 |

| Chest pain | 32 | 22 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 0.01 | 2.6 (1.2-6) | NA | 1 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 32 | 0.4 | |

| Shivers | 113 | 93 | 23 | 20 | 26 | 0.6 | 1.1 (0.6-2) | 1 | 4 | 7 | 44 | 4 | 36 | 8 | 32 | 0.004 |

| Headache | 108 | 88 | 22 | 20 | 26 | 0.3 | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | NA | 5 | 31 | 5 | 45 | 10 | 40 | 0.01 | |

| Myalgia | 69 | 54 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 0.1 | 1.5 (0.8-2.8) | NA | 3 | 19 | 3 | 27 | 9 | 36 | 0.01 | |

| Arthralgia | 55 | 44 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 0.4 | 1.3 (0.6-2.7) | NA | 1 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 8 | 32 | 0.01 | |

| General malaise | 164 | 130 | 33 | 34 | 44 | 0.04 | 1.6 (1.2-2.6) | 7 | 28 | 6 | 38 | 7 | 64 | 14 | 56 | 0.01 |

| Rhinorrhea | 124 | 106 | 26 | 18 | 23 | 0.6 | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | 4 | 16 | 4 | 25 | 3 | 27 | 7 | 28 | 0.4 |

| Polypnea | 138 | 115 | 29 | 23 | 30 | 0.8 | 1 (0.2-1.8) | 11 | 44 | 2 | 13 | 4 | 36 | 6 | 24 | 0.2 |

| Vomiting | 94 | 75 | 19 | 19 | 24 | 0.1 | 1.4 (0.7-2.5) | 5 | 20 | 3 | 19 | 5 | 45 | 6 | 24 | 0.2 |

| Abdominal pain | 108 | 91 | 24 | 17 | 22 | 0.7 | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | NA | 7 | 44 | 5 | 45 | 5 | 20 | 0.002 | |

| Conjunctivitis | 45 | 35 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 0.9 | 1.5 (0.7-3.2) | 3 | 12 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 18 | 3 | 12 | 0.8 |

| Cyanosis | 45 | 40 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 0.3 | 0.6 (0.2-1.6) | 2 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Sudden onset | 317 | 258 | 63 | 59 | 75 | 0.05 | 2.5 (1.5-4) | 17 | 68 | 14 | 88 | 10 | 91 | 17 | 68 | 0.1 |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

*χ2 test;

**linear χ2 test.

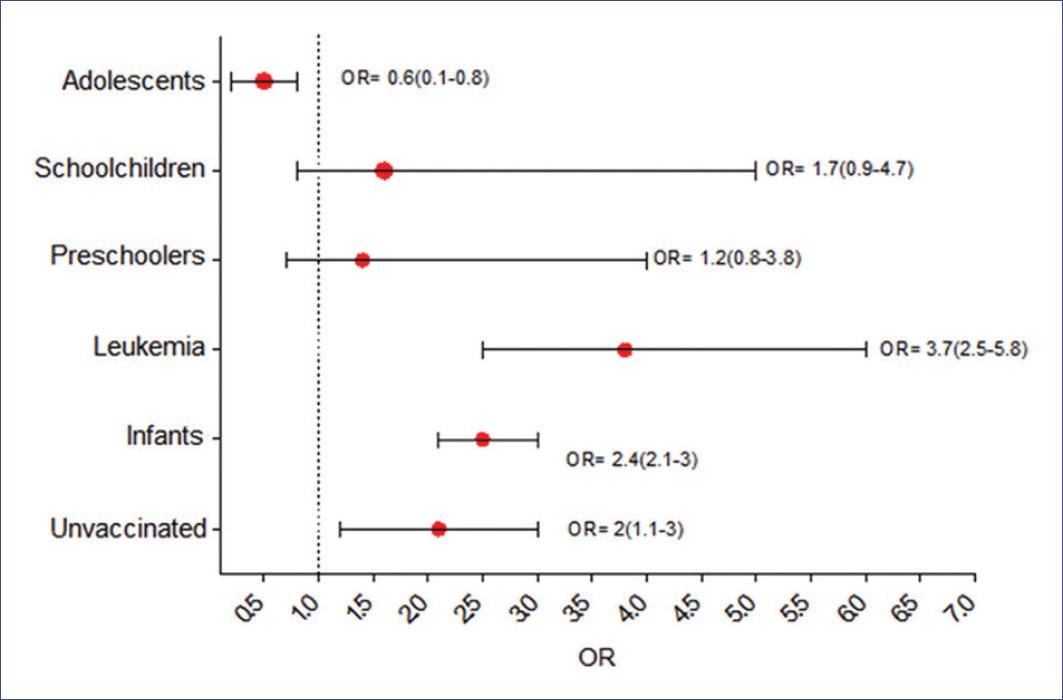

A total of 11 patients (19.3%) required assisted mechanical ventilation. Bivariate analysis showed that the variables associated with this outcome were age < 2 years, history of not having influenza vaccination, sudden onset of symptoms, and hemato-oncologic pathology. OR values are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 Calculated odds ratio for children infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome type 2 coronavirus requiring mechanical ventilatory support. Unvaccinated refers to no seasonal influenza vaccine.

Only one patient from the SARS-CoV-2 group died. This patient arrived at the emergency department in asystole and did not respond to resuscitation maneuvers.

Discussion

In this pediatric series of patients treated for respiratory symptoms in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we were able to describe the clinical characteristics of 510 children who were treated in an emergency department.

The frequency of disease by the confirmatory test was 15% (i.e., 1.5 out of 10 patients evaluated). This proportion is compatible with that reported in other pediatric series, in which the frequency of diagnosis ranged between 10 and 15%8. This pattern could be explained by the fact that the preventive strategy of most countries has been to confine this population group due to the limited possibility of adherence to standard protection measures9.

The population in this study demonstrated a bimodal diagnosis pattern: 64% of cases were equally distributed among children < 2 years and adolescents. The reason for this distribution is yet unclear. However, the pathophysiological justification is by the mechanism associated with the angiotensin II inhibitory enzyme10 and the thymus-dependent immune response11.

In this case, the sudden onset of symptoms, as well as general malaise, and chest pain were found to be the symptoms most associated with a positive test. These results differ from those expected in adults, as shown by a meta-analysis conducted by Rodriguez-Morales et al., who reported, after reviewing 19 articles, that fever, cough, and dyspnea were the most representative symptoms in the adult population and were associated with a worse outcome12. This discrepancy was present because the frequency of respiratory complications and the need for mechanical assistance were not different from that of subjects with no SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, it represented 11% in this series of patients.

The contact of children with a confirmed case of COVID-19 was the variable most associated with the development of the disease and is the leading cause of contagion within families, with primary caregivers being the ones initially affected13. Vertical infection through the birth canal or transplacental route has been reported14. However, in this study, these modes of transmission could not be assessed, because the infants were not attended in our hospital emergency department but were referred by other centers directly to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Another condition that should be discussed is the history of influenza vaccination and its risk association with the need for intubation. Although only 23% of all children were vaccinated, the subgroup of intubated children showed an OR of 2.5. Coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 with other respiratory viruses or vaccine-preventable bacterial cases of pneumonia has been described since the beginning of the pandemic15. This observation is consistent with our results since the first cases of COVID-19 in Mexico, and the first week of Phase III developed during the expected season of respiratory infections by influenza. Moreover, some of the cases detected in March were also analyzed for other respiratory viruses. An association of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza was found in 13% of these cases.

COVID-19-related mortality in our emergency department was < 2%, accordingly with reports by multicenter studies, such as Critical Coronavirus and Kids Epidemiology, conducted in 17 critical care centers in the United States, where mortality from SARS-CoV-2 was 6%16.

Tiago et al. recently published a meta-analysis that included 28 studies (1124 cases) of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which reported moderate symptoms in 46% of patients; mechanical ventilation was required in 10 cases. Concerning clinical data, the most frequent sign was fever (47%), and the most prevalent symptom was cough (41.5%). In this regard, it should be noted that the articles included were only cases with confirmed patients. In that population, the proportion of subjects with endotracheal intubation was higher because of the coexistence with other pathologies17.

Our results show that the conditions of our hospital represent the scenario of the pandemic in the pediatric population in Mexico at the first contact level. It also delimits a population at risk, with specific symptoms and relevant background. Therefore, pediatricians can make a better decision when it comes to prioritizing resources. Consequently, infants and adolescents with sudden onset of symptoms (chest pain for children who can report it) and a history of contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient may be the primary factors to be screened with testing. Furthermore, positive patients with no history of influenza vaccine are at higher risk of severe complications. Fever is a common sign in patients with and with no confirmed infection, which determines one of the main reasons for consultation. However, it is not possible to discriminate between them.

The present results are descriptive and exploratory of the general scenario. Laboratory studies, short- and long-term follow-up, and measurement of potentially confounding variables are necessary to achieve an accurate prognostic study without misclassification, memory, and inclusion biases. Furthermore, the extent of the treatments applied should be assessed.

In pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection suspicion, the frequency of positive test results was 15% (infants and adolescents represented 64% of confirmed cases). The contact with a confirmed case, sudden onset of symptoms, and chest pain were factors associated with a positive test result.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)