Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Boletín médico del Hospital Infantil de México

versión impresa ISSN 1665-1146

Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. vol.62 no.4 México jul./ago. 2005

Tema pediátrico

Ethical aspects of the extreme premature newborn

Aspectos éticos en los recién nacidos prematuros extremos

Jorge L. Hernández– Arriaga1, PhD, Kenneth V Iserson2, M.D., MBA

1 Professor of Pediatrics and Bioethics, Member of the Bioethics Committee of the Mexican Academy of Pediatrics, Director, Centro de Investigaciones en Bioética, University of Guanajuato, Guanajuato, Mexico;

2 Professor of Emergency Medicine, Director, Arizona Bioethics Program, University of Arizona College of Medicine Tucson, AZ, USA.

Reprint request:

Jorge L. Hernández PhD,

Centro de Investigaciones en Bioética, Universidad de Guanajuato,

20 de enero 929, Col. Obregón,

C.P. 37320, León, Guanajuato, México.

Date of reception: 27– 08– 2003.

Date of approval: 14– 07– 2005.

Abstract

As neonatology continues to advance medical knowledge and situations surrounding the care of ill and premature newborns, each step introduces ill– defined methodologies, unknown outcomes, and increasing costs. In countries such as Mexico, the government hospitals assume the cost of such treatments. It is, therefore, incumbent on the entire society, rather than simply the medical community, to enter into the debate about which of these tiny patients should be treated, how aggressive such treatment should be, and what outcomes are acceptable.We suggest an appropriate strategy for countries like Mexico, with an intermediate policy between treating all the very low birth weight babies (VLBW) and offering strict limits, where all the parts are involved in the decision making process.

Key words. Very low birth weight; ethics; treatment limits.

Resumen

La neonatología continúa avanzando en el conocimiento médico y en las condiciones que rodean el cuidado de neonatos enfermos y prematuros. Cada paso introduce metodologías definidas para cada enfermedad, resultados inciertos, y costos crecientes. En países como México, generalmente estos niños son atendidos al través de los hospitales públicos; por tanto, el Estado asume el costo. Es, por consiguiente, responsabilidad de la sociedad entera, y no solo simplemente de la comunidad médica, discutir sobre qué se debe hacer en pacientes diminutos, hasta dónde realizar tratamientos agresivos, y qué resultados son aceptables. Se propone una estrategia adecuada a la situación de México, intermedia entre tratar a todos los prematuros de muy bajo peso u ofrecer límites estrictos, donde se involucren todas las partes en la toma de decisiones.

Palabras clave. Muy bajo peso al nacer; ética; límites al tratamiento.

One hundred years ago, only a few physicians were willing to brave the complexities of a dedicated pediatric practice. Infant mortality, especially deaths in the neonatal period, were so common that many women's graves were surrounded with the tiny stone markers of their children that did not survive infancy.1 With the development of antisepsis, scientifically based obstetrics, antibiotics, and immunizations, the situation changed dramatically.

In the 1960s, the specialty of neonatology emerged with neonatal intensive care units (NICU) and mechanical ventilators adapted to infant use. In the United States, support for neonatal research was stimulated when, in 1963, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy delivered a 2 100 g premature baby who, despite enormous efforts, died from respiratory failure. This event stimulated a research effort that eventually resulted in increased premature infant survival rates due to the use of exogenous surfactant, better neonatal fluid management, and more accurate medication dosing and administration.

At present, some countries, such as the United States, have a significant number of survivors among babies weighing no more than 500 g. In countries with fewer resources, such as Mexico, neonatal survival varies by hospital, but physicians have experienced consistent success with infants weighing between 700 and 1 000 g.This has been due not only to neonatal treatment, but also due to increased prenatal care and the increasing numbers of high– risk mothers delivering in neonatal centers. With Mexico's (and other marginal economies') limited budgets for advanced medical interventions, these actions have diminished the need to expend large amounts of healthcare resources on respirator– dependent low– weight infants.

Neonatologists' ability to save more infants has, however, resulted in more children surviving their NICU stays with adverse sequelae—a result often exaggerated among both the medical and non– medical communities. Although more newborns with unfortunate neurological and multisystem abnormalities do emerge from NICUs, these complications are disproportionately found among smallest neonates, who spend more time on ventilators and have more invasive procedures performed. Even among this group, though, results have greatly improved in recent years.While there are, undoubtedly, more children today with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, and some degree of cerebral palsy after their NICU stays, a greater proportion than ever of low– birthweight babies go on to live their lives with minimal or no sequelae.With new scientific advances, these results should only improve over time.

Treatment costs

Despite the success of medical interventions for premature infants, economic constraints on the amount of NICU care that healthcare systems can provide are an ongoing reality. Since even under the best circumstances, approximately 7% of newborns are premature, and 5% of those born at term require some type of specialized treatment, the cost to treat these patients can be enormous.2 In the United States, for example, 65% of the total budget dedicated to neonatal care goes to those infants weighing less than 2 500 g at birth, with such treatment often averaging $366 000.00.3 In Spain, such newborns are often hospitalized from two to four months, with each one sustaining about 15 million pesetas (nearly $90 000.00) in medical costs.4,5

In Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico, we expend about 850 000.00 pesos ($80 000.00) for each similar infant in our NICUs. In the Mexican medical system, the government generally pays these costs at public or Social Security hospitals. Few private Mexican hospitals have fully equipped NICUs and relatively few Mexicans have the ability to pay such enormous medical bills. To get the best neonatal care for their patients, Mexican pediatricians have become expert at "gaming the system." Many Mexican infants admitted to private hospital NICUs are quickly transferred to Social Security hospitals, although they may not always be eligible, that is, obtain their insurance only after the baby be born. In other cases they are indigents or their parents can not pay the due of the National Social Security System (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social), in these cases the patients are transferred to public hospitals. As a result, the high– intensity NICUs at government– run hospitals have been inundated, diminishing the available care and resources for each patient. Because the entire Mexican economy pays the cost of such treatment, the question of which low– birthweight infants to treat and how physicians should make such decisions, is one of national importance.

It is not, however, simply a matter of money. While very low birth weights (VLBW) infants incur even more expenses than the normal ill neonate, the cost to families, patients, and society must be measured not only in terms of money, but also as the resulting quality of life.5 The question, then, in most countries is how much of their medical resources should they expend on these tiny patients—and which infants should receive them.

Clinical uncertainty

Of course, it is often unclear which infants will have long–term medical problems. But between 1.5 and 2% of newborns have some type of malformation, many of which are trivial, minimally affecting the person throughout their life.6 In live–born infants, very few serious malformations occur, especially those incompatible with life or for which no effective treatment exists. However, when serious malformations do occur, they often generate heated debate among clinicians and within families about the resulting medical and ethical dilemmas. The combination of extreme prematurely and malformations are another factor that even makes more difficult the taking of decisions as for the limits that it would be necessary to the medical attention of these babies.

While neonatologists use existing science and clinical experience to provide evidence–based treatment resulting in more consistent outcomes for some conditions, they continually push the envelope for other, often previously untreatable disorders. In doing so, they have moved into regions of uncertainty, attempting to correct conditions that stretch their abilities and knowledge. In many of these cases, despite maximal efforts, there are unexpected results. Recognizing this, Javier Gafo, philosopher, biologist and Spanish priest, compared neonatology with "a career of obstacles in the darkness—today we can jump over a barrier, but we ignore subsequent obstacles that are the ones that we will soon trip over in the course of treatment".4 While in some cases, such as premature with a trisomy 18, the neonatologist can generally predict the final outcome, in many other instances, like a severe RDS in a 700 g babe the prognosis is much more obscure. In these situations, the neonatologist can only offer parents a range of possible therapeutic avenues and an uncertain outcome.

A potential response?

What direction and range of options should neonatologists give parents in these circumstances? Extreme postures exist, from those completely "tanatists" until those completely "vitalists", some centered in the quality of life and therefore utilitarian, and on the other hand attached to fundamental principles, sometimes sustained in philosophical arguments (kantism) and others in religious arguments. Mexico is a country of contrasts that receives the influence of the postures of the rest of the world, but that adapts to the own circumstances and it also enriches with its own contributions. We seek then, to analyze the existent currents and finally the reality of, and from Mexico.

Putting limits.The "tanatist" point of view

Euthanizing newborns (as well as older individuals) has been practiced since ancient times.The Polis in Sparta and Aristotle in Athens endorsed this practice (Politics 7.16). Plato, Aristotle's teacher, wrote that in his ideal republic, citizens who were healthy in body and soul would be protected, while those with physical anomalies or intellectual limitations would be allowed to die (Republic 5.16). In Rome, the Lex Pompeia Patricidiis gave parents absolute power over their children (patrias potestas, repealed in the year 135 a. C.), including lawfully eliminating unwanted offspring (repealed in 374 a. C.).5 The extensive history of infanticide has manifested itself differently in various cultures. In China,Japan and India, the practice was related to trying to limit the number of women in the population, as they were believed to be less– productive members of their families and society. In Australia, New Zealand, and among Arctic inhabitants, the rate of infanticide varied with the community's resources and was a way to ration the resources necessary for survival. Among the Swahili of Africa, infanticide was punishment for illegitimacy or illness.7–9

Some modern bioethicists have defended infanticide. Australian philosopher Eike Henner Kluge, for example, asserts that parents are the only ones that can decide what is best for their children. If children are born without obvious abnormalities, their parents are the legitimate representatives of their rights. He asserts that the situation changes only when parents show signs of rejecting their disabled child (even minimally). In those cases, he believes that doctors should step in to safeguard the adults' quality of life.9 Since the births of malformed or handicapped neonates cause serious economic, social, family problems for parents, he projects that such newborns would altruistically sacrifice themselves for the parents' and doctors' benefit. Concluding that to prolong the infant's agony would be cruel and immoral; he advocates the rather radical solution that in these situations euthanasia is not only permissible, but also obligatory. Therefore, in these situations he suggests that physicians should offer a quick and easy death rather than allowing the infants to cruelly die of starvation or dehydration.

Other authors, such as the Australian, Peter Singer, think that newborns with malformations or with a risk of having serious sequelae should be eliminated. However, he extends his argument to the assertion that even totally healthy children can be killed if their parents reject them or they are at risk of suffering ill treatment later on. He would limit the period during which parents could eliminate their neonates to 28 days, since he believes that, until then, neonates have not established social contact with their parents.

While theologian Joseph Fletcher believes that good ends cannot justify using any means to achieve them, he also asserts that euthanasia may be justified to avoid the misery, suffering and dehumanization of some disabled newborns. In these cases an appeal to an "ethics of the quality of life" legitimizes this behavior, representing a higher or proportionate benefit.10,11 All these authors then, seem to condone sacrificing the neonate if the financial, social, or emotional benefits seem to outweigh the costs.

Arguably, distinguishing which lives are worthy to be lived would sooner or later be applied to other groups of people, such as the old, abandoned, demented, or chronically ill. In response to this potentiality, Peter Singer suggests that societies that have permitted such elimination of citizens respected the categories of subjects who could be purged. Nevertheless, the history of Nazi medicine, as well as the recent Dutch experience with voluntary euthanasia (attended suicide) belies Singer's assertion.

Today, due to financial, emotional, and family pressures, some neonatologists and obstetricians rush to decide who should die based on quality– of– life assessments, so that the infants will not face possible suffering in later life. In some cases, parents request physicians to compassionately euthanasize their newborn to avoid the suffering (theirs, their family's and the infants) that result from aggressive treatment and a potentially unhealthy child.

Medicalizing the decisions – universal treatment

The other extreme is for neonatologists to aggressively treat all neonates using all available resources.This also seems to be a morally dubious response – as well as being impractical. However, in Sweden, neonatologists generally treat seriously ill newborns based strictly on the statistical probability of their survival. That is to say, they take into consideration the chance of an infant's survival based on their gestational age and weight, and the presence of malformations incompatible with life. In cases in which a newborn survives with sequelae or malformations, the government offers them all appropriate services.

In England, physicians have more leeway, caring for all newborns, with the caveat that they will remove life support if the baby shows signs of severe or irreversible brain damage. In the United States, the last few years have seen major advances in newborn resuscitation modalities.Yet, implementation has not been uniform due to diminishing resources, changing relationships between healthcare providers and parents, and the law's silence on most of these issues. There has also been a proliferation of "interested parties" who have become involved in the decision– making process, including the state's determination of the infants' "best interest." These factors motivate many neonatologists to treat all potentially viable newborns.

An ethical approach

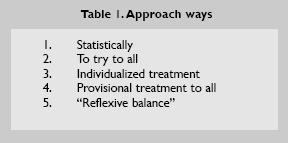

The most reasonable and ethically justifiable approach, intermediate between the previously described practices, is to recognize that physicians must often make decisions about neonates based on incomplete prognostic information. To counteract purely subjective "quality of life" decisions, clinicians should be free to use their best professional judgment, balancing this with input from the parents at nearly every stage of the decision– making process. In the table 1 we can observer the different signal postures, the alternative of the balance reflexive proposes to involve or at least try to involve to all the other postures in balanced form, trying to respect the values of all the participants, especially that of the parents and the interests and the baby's rights.

In the case of extreme prematurity (less than 500 g) the decisions must be not to treat or treat only in special circumstances and in very high specialized NICU. In the case of not extreme prematurity and malformed newborns, the first decision, solely within the physician's realm, is whether the abnormalities are compatible with life. This may vary, depending upon the resources available in the country or region in which the child is born. If the malformations are too severe, the decision must be not to treat. If the malformations are correctable without leaving serious sequelae, and resources are available, treatment should proceed.

The problem is centered in those newborns whose survival is uncertain and those who probably will survive, but with serious, but not life– threatening, sequelae. In the first group, where uncertainty exists about survival, the most reasonable approach is to use a time– limited trial of therapy, with the parents' consent. Initial treatment is begun but, if appropriate progress is not made or the infant regresses despite treatment, it can be stopped. If treatment results in improvement without devastating sequelae, such as massive intracranial bleeding, the treatment is continued.

The second group is those who will survive, but with sequelae. Ceccheto and others have argued that we should not make decisions about neonates based on whether they will grow to be perfectly healthy adults. This makes sense, since quality– of– life valuations are nearly impossible to make for our future selves, let alone others.5 While adults' perspectives on life change totally if they suddenly are forced to use crutches or wheelchairs, a child who has always lived that way may consider their situation normal and not at all detrimental to achieving happiness or their life goals.12–14 While all newborns with sequelae need not be indiscriminately supported, using the criteria of "quality of life" is particularly slippery. It is necessary to remember the intrinsic dignity of every human life and to carefully analyze the situation of each ill, or VLBW newborn in order to make the correct ethical decisions.

That being said, in making such decisions, one must also consider the "excessive suffering" of families and society from the heavy, and sometimes seemingly impossible burden that seriously ill neonates may produce. Both the families and society have issues that must be addressed within the decision– making context. For example, over the past decades, societies throughout the Americas and Europe have become environments in which the disabled can more easily function and perform most of the tasks of daily living.

Conclusions

While philosophers differ on how to approach seriously ill and VLBW neonates, clinicians and families must make difficult decisions and act upon them. Although once– widely practiced, active infant euthanasia contravenes both modern moral and legal precepts. Yet, continuing futile interventions is harmful to the infant, the family, the medical staff, and the community, including others who could benefit from such interventions. As of now, Mexico does not have a consistent medical ethic guides or laws that address the treatment of VLBW, very ill or malformed infants. Promoting such a moral consensus and appropriate legislation is vital to Mexico, as it will be for the many other countries in the same situation.

Basing decision making about treating VLBW or malformed neonates, purely on biological or statistical criteria reduces the newborn to an object that can be conserved or eliminated. It seems to disregard the basic concept that human beings are more than simply cellular aggregates, or that humans have value in themselves, separate from their ultimate potential.The more practical problem is that when statistical probabilities govern treatment decisions, the seriously ill or smaller infants will not be treated, effectively halting progress in neonatology. If neonatologists had followed this approach in the 1960s, we would still not have survivors who weighed less than 2 000 g at birth.

The approach of treating all neonates until clinicians are "almost certain" that they won't survive, results in most survivors, although more of these infants will survive with significant anomalies. While vitalists such as Javier Gafo claim that it "is better to err on the side of the life",4 some doctors may use such philosophies to act cruelly in the name of therapy, relegating parents to the role of mere spectators. Using this strategy, decisions are often "medicalized," separating them from any ethical basis.

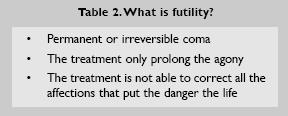

In general, we must treat in any emergency and in case of doubt. But there is not obligation to treat in case of evident futility (Table 2). In those cases may be exist a general consensus. In our country like other developing countries is fundamental to establish strategies to treat efficient and ethically correct this babies, making objective the measurement of results, looking for a posture balanced reasonably that finally arrives to the legislations, without forgetting that it is not alone a consensual, scientific or juridical matter, but something much deeper and more transcendental.

However, neither of these treatment strategies is without problems.The most reasonable method for making such decisions is, in each case, to weigh the available statistical prognostic evidence, include the parents in the decision– making process, and opt for what the group feels is the most appropriate course of action. Time– limited trials of therapy or specific stopping points will often be an important part of such decisions. Finally, unless or until there is sufficient data to make a decision to the contrary, opt for life. The rationale for this is simple: doing otherwise cancels further options; death is final.

References

1. Iserson KV. Death to dust what happens to dead bodies? Tucson, AZ:Galen Press, Ltd.;2001. [ Links ]

2. Wyatt JS. Neonatal care: withholding or withdrawal of treatment in the newborn infant. Baillie's Beste Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 4:503– 11. [ Links ]

3. Rogowski JA, Horbar JD, Plsek PE, Baker LS. Economic implications of neonatal intensive care unit collaborative quality improvement. Pediatrics. 2001; 107:23– 9. [ Links ]

4. Gafo J. Problemas éticos en Neonatología. En: Anónimo. Ecos del IV Encuentro de la Federación Latinoamericana de Instituciones de Bioética. Guanajuato, México: Ed. Universidad de Guanajuato; 1995. p. 349– 66. [ Links ]

5. Cecchetto S. Dilemas bioéticos en medicina perinatal. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ed. Corregidor; 1999. [ Links ]

6. Hernández– Arriaga JL, Cortés– Gallo G, Aldana– Valenzuela C, Ramírez– Huerta AC. Incidencia de malformaciones congénitas externas en el HGOP 48 en León, Gto. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1991; 10: 717– 21. [ Links ]

7. Piers MW. Infanticide, past and present. New York: Norton, Ed.; 1978. [ Links ]

8. Westermarck EA.The killing of parents, sick persons, children feticide. En: Westermarck EA, editor The origin and development of moral ideas. London: McMillan; 1989. p. 1906– 8. [ Links ]

9. Silverman WA Mismatched attitudes about neonatal death. En: Silver T editor Ethical issues in the treatment of children and adolescents. New Jersey: Slack; 1983. [ Links ]

10. Fletcher J. Ethics and euthanasia. Am J Nurs. 1973; 73:110– 3. [ Links ]

11. Fletcher J.The right to die:The theologian comments. Atlantic: Monthly; 1968. p. 62– 4. [ Links ]

12. Moreno J. Ethical and legal aspects in the attention of neonates with malformations. Clin Perinatol North Am. 1987; 2:130– 7. [ Links ]

13. Moss AH, Oppenheimer EA, Casey P, Cazzolli PA, Roos RP, Stocking CB, et al. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis receiving long– term mechanical ventilation: advance care planning and outcomes. Chest 1996; 110:249– 55. [ Links ]

14. Kuhse H, Singer P. Should the baby live? The problem of handicapped infants. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [ Links ]