Introduction

Since the cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) programs emerged in Mexico in 1944, the development of centers that provide professional and interdisciplinary care has been an unstoppable and constant reality, not only thanks to the growth of scientific evidence but also to the clinical results obtained with this therapeutic strategy1.

Mexico is located in North America and is ranked as the 10th most populous country in the world, with more than 126 million inhabitants, and the 13th largest with an area of almost 2 million square kilometers2. It is integrated by 32 states, and the official language is Spanish. The estimated gross domestic product (GDP) is 140,624.3 million dollars, (13th in the world); and with a yearly per capita GDP of 1,080.75 dollars3, where cardiovascular diseases represent the first place of mortality for 2021, after COVID-19 with 132,742 deaths in the first half of the year4. Multiple associations worldwide have recommended CR programs in almost all heart diseases, based on their benefits5-9. The knowledge and spreading of CR programs are increasing and standardized at international level4.

Despite the SARS-COV-2 pandemic caused a high lethality rate, cardiovascular (CV) diseases remained the leading cause of death (regardless of sex, with 141,873 deaths recorded in just the first half of 2020)10. In addition, the pandemic caused a significant drop in the country's economy with commercial, and care activities work closure, impacting directly in health sector, and increasing further the already health and social inequalities11.

In this context, CR centers underwent an accelerated transformation in solidarity due to the need to deal COVID-19 and its sequelae; in consequence, some CR centers closed and others made adjustments to their processes. Fortunately, over time during this pandemic, some centers reopened providing CR services, and others integrated cardiopulmonary rehabilitation (CPR) into their services to treat post-COVID patients as well.

Due to the high demand of patients who require CR, as well as the growing number of professionals who provide this service (with highly specialized academic training in CR and certification by the Mexican Council of Cardiology), and considering the measures imposed by health authorities until COVID pandemic, arises the need to know the conditions of the CR units and compare them with those censused and registered in both RENAPREC-200912 and RENAPREC II-201513 studies.

The objective of this National Registry is to follow-up those existing CRs and learn about new CR units in Mexico through the comparison between the two previous registries. This comparison will be focused on diverse CR activities such as assistance training, and certification of health professionals, barriers, reference, population attended, interdisciplinarity, permanence over time, growth prospects, regulations, post-pandemic condition, integrative characteristics, and research.

Methodology

RENAPREC III-2022 is a descriptive study developed throughout the Mexican territory, as a follow-up of previous national registries. Any CR center that offered CR program or CPR service was included in the study. The recruitment strategy was developed as follows:

− All participating centers in RENAPREC-2009 and RENAPREC II-2015 were called to participate.

− Those institutions with a training course for specialists in CR participate by seeking centers opened by their graduates.

− Researchers were assigned by region to make a local census from geographical areas of distribution.

− Members of other societies involved in academic activities were contacted.

− Units directly recommended by other units managers were included in the study.

To achieve a regional census that included most of the information about CR units in the country, the search was divided into seven evaluated regions where the 32 states were gathered and distributed in: center, southeast, east, west, north, northwest, and Bajio area. After this investigation and the recruitment criteria were reached, they were personally contacted to send the survey and corroborate the results directly with the information providers.

Selection criteria and study development

We included all CR centers in Mexico that responded and completed the survey. All incomplete reports were disqualified from the study. The survey included questions that covered various aspects of CR and CPR programs. These questionnaires were sent by Email. All information was verified by each informant and was double-checked. A database was made for the classification of variables. Comparisons between the 3 censuses and the participating centers in RENAPREC III-2022 were also independently evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation), median (minimum or maximum), and frequency (percentages) as appropriate. χ2, ANOVA, t-test, and Wilcoxon rank tests were performed for comparison. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 22 program for Windows.

Results

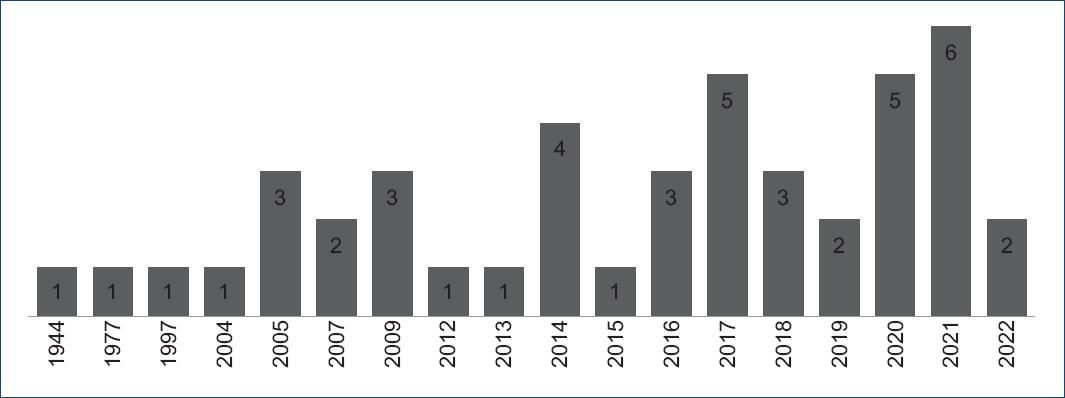

Throughout the study, data were collected from 45 CR centers in the 32 states of Mexico, 75.5% (n = 34) were private practice units and 24.5% (n = 11) public practices. In this RENAPREC III-2022, 67% of the CR units are new, 33% were part of RENAPREC II-2015 (n = 15), and 17 have continued since 2009 (Fig. 1). Centers that did not participate in this registry can be found in the previous publications. The first CR center in Mexico was at National Institute of Cardiology "Ignacio Chávez" (INCICh), and in the past decade, 33 centers have been opened. It is noteworthy that, during the pandemic (after the year 2020), 13 centers were opened (Fig. 2).

Most of the Chief Service, Directors, or seconded staff (60%, n = 27) that provided the information have current certification by their respective Councils of Medical Specialties (CONACEM) in cardiology or rehabilitation medicine as appropriate, and 49% have current certification in the subspecialty in CR. Only 31.1% (n = 14) of the centers surveyed are certified by the official institution for CR in Mexico, SOMECCOR. Table 1 shows that the results of the 45 centers included in this registry.

Table 1 CR centers surveyed in our national registries (RENAPREC)*

| RENAPREC III-2022 CR centers | City | 2022 | 2015 | 2009 | Attention | Opening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Instituto Nacional de Cardiología "Ignacio Chávez", Servicio de Rehabilitación Cardiaca (INCICh) | Mexico City | x | x | x | Public (S.S.) | 1944 |

| 2 | CMN Nacional "20 de Noviembre", Servicio de Rehabilitación Cardiaca ISSSTE | Mexico City | x | x | Public (ISSSTE) | 1977 | |

| 3 | SOCAYA | Ags, Ags | x | x | Private | 1997 | |

| 4 | Centro de Rehabilitación Cardiopulmonar, Clínica Lomas Altas | Mexico City | x | x | x | Private | 2004 |

| 5 | Cardiorehabilita | Cuernavaca, Morelos | x | x | Private | 2005 | |

| 6 | Instituto del Corazón de Querétaro | Querétaro, Querétaro | x | x | Private | 2005 | |

| 7 | Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación "Luis Guillermo Ibarra Ibarra" | Mexico City | x | x | x | Public | 2005 |

| 8 | Cardioactivo GDL | Guadalajara, Jalisco | x | x | x | Private | 2007 |

| 9 | Cardiología Integral Yestli | Mexico City | x | x | x | Private | 2007 |

| 10 | Unidad de Estilo de Vida y Rehabilitación Cardiaca, Ags | Ags, Ags | x | x | Private | 2009 | |

| 11 | Centro Médico Naval | Mexico City | x | x | Public (SEMAR) | 2009 | |

| 12 | Hospital Ángeles Puebla | Puebla, Puebla | x | Private | 2009 | ||

| 13 | Hospital Central Sur de Petróleos Mexicanos | Mexico City | x | x | x | Public (PEMEx) | 2009 |

| 14 | Unidad de Medicina Física y Rehabilitación Región Centro IMSS | Mexico City | x | x | Public (IMSS) | 2012 | |

| 15 | Instituto Cardiovascular de Saltillo ISSSTE | Saltillo, Coahuila | x | x | Private | 2013 | |

| 16 | Clínica de Obesidad y Metabolismo | Querétaro, Querétaro | x | Private | 2014 | ||

| 17 | Cardiofit | Mexico City | x | x | Private | 2014 | |

| 18 | Centro Médico del Rio | Hermosillo, Sonora | x | Private | 2014 | ||

| 19 | Hospital Central Militar | Mexico City | x | Public (SEDENA) | 2014 | ||

| 20 | Hospital Dalinde | Mexico City | x | x | Private | 2015 | |

| 21 | Unidad de Medicina Física y Rehabilitación Región Norte IMSS | Mexico City | x | x | Public (IMSS) | 2015 | |

| 22 | CEMERC, Centro Mexicano de Rehabilitación Cardiaca | Mexico City | x | Private | 2016 | ||

| 23 | Instituto Cardiovascular de Hidalgo | Pachuca, Hidalgo | x | Private | 2016 | ||

| 24 | Centro de Rehabilitación Cardiaca CLINIDEM | San Luis Río Colorado, Sonora | x | Private | 2016 | ||

| 25 | Clínica Médica C.M.A. Star Médica | Mérida, Yucatán | x | Private | 2017 | ||

| 26 | Servicio de Rehabilitación Cardiovascular Ixtapaluca | Ixtapaluca, Edomex | x | Public (S.S.) | 2017 | ||

| 27 | Cardiovascular Solutions | Chapala, Jalisco | x | Private | 2017 | ||

| 28 | Centro Cardiológico Mexicali | Mexicali, BC | x | Private | 2017 | ||

| 29 | Clínica AMAR | Durango, Durango | x | Private | 2017 | ||

| 30 | Clínica de Rehabilitación Cardiaca, CICOR | Guadalajara, Jalisco | x | Private | 2018 | ||

| 31 | Centro de Rehabilitación Cardiopulmonar Smart Heart | Puebla, Puebla | x | Private | 2018 | ||

| 32 | Hospital Angeles de León | León, Guanajuato | x | Private | 2018 | ||

| 33 | Medicar Fitness | Torreón, Coahuila | x | Private | 2019 | ||

| 34 | Centro Integral de Rehabilitación Cardiovascular "Cardioneumo" | SLP, SLP | x | Private | 2019 | ||

| 35 | REHADAPTA | Mérida, Yucatán | x | Private | 2020 | ||

| 36 | Unidad de RHC del Hospital San Diego | Cuernavaca, Morelos | x | Private | 2020 | ||

| 37 | Centro de Rehabilitación Cardiovascular Montejo | Mérida, Yucatán | x | Private | 2020 | ||

| 38 | Hospital Puerta de Hierro Sur | Guadalajara, Jalisco | x | Private | 2020 | ||

| 39 | Fisio Heart | Chihuahua, Chihuahua | x | Private | 2021 | ||

| 40 | ProcorLab Rehactive | Mexico City | x | Private | 2021 | ||

| 41 | Servicio de Rehabilitación Cardiaca y Pulmonar | San Bartolo Coyotepec, Oaxaca | x | Private | 2021 | ||

| 42 | Grupo San Ángel Inn – Universidad | Mexico City | x | Private | 2021 | ||

| 43 | Servicio de Rehabilitación Cardiaca, CMN de Occidente IMSS | Guadalajara, Jalisco | x | Public (IMSS) | 2021 | ||

| 44 | Heart Rate | Torreón, Coahuila | x | Private | 2022 | ||

| 45 | Hospital Regional "Lic. Adolfo López Mateos" ISSSTE | Mexico City | x | Public (ISSSTE) | 2022 | ||

Ags: Aguascalientes; BC: Baja California; CDMx: México City; SRLC: San Luis Río Colorado; EdoMex: Estado de México; SLP: San Luis Potosí; SBC: San Bartolo Coyotepec; RCyMD: Rehabilitación Cardíaca y Medicina del Deporte; NMC: National Medical Center; IMSS: Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social; ISSSTE: Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado. SS: Secretaría de Salud. SEMAR: Secretaría de Marina. PEMEx: Petróleos Mexicanos. SEDENA: Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional.

About distribution: 36% (n = 16) of CR units are congregated in Mexico City and the others (n = 29) are distributed in the rest of states (Fig. 3); 69% (n = 31) are located within a hospital, while 31% (n = 14) remain as centers independent of hospital units ("Stand Alone Centers"). The number of centers necessary to cover the care of patients in need of CR in RENAPREC II-2015 was 640; now, the number of centers needed in RENAPREC III-2022 is 667. In this sense, according to the census carried out among the centers included, the median reference percentage of patients who are candidates for CPR programs is 9% (min 1%, max 70%).

Figure 3 General distribution and concentration by state of CR centers in Mexico (RENAPREC III-2022).

Characteristics of the centers and patients included

The patients' age included in CR programs is 58 ± 5 years, with a higher percentage of male patients (74%). The body mass index of the patients was 29 ± 2 kg/m2, with an abdominal perimeter of 100 ± 7 cm. The programs have interdisciplinary care, and Table 2 shows the comparison of health personnel included variables among the three registries, and patients characteristics included in the programs of the different CR centers.

Table 2 Growth variables throughout our national registries

| Variables | RENAPREC I (2009) | RENAPREC II (2015) | RENAPREC III (2022) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centers included and distribution | ||||

| Number of centers | 14 | 24 | 45 | |

| CDMX: total ratio | 8 (57%): 6 (43%) | 16 (67%): 8 (33%) | 16 (35%): 29 (65%) | |

| Public: private ratio | 5 (36%): 9 (64%) | 10 (42%): 14 (58%) | 12 (27%): 33 (73%) | ns |

| Hospital-based | 12 (86%) | 15 (63%) | 31 (69%) | ns |

| Phases of cardiac rehabilitation | ||||

| Phase I | 5 (35%) | 10 (41.6%) | 32 (71%) | ns |

| Phase II | 14 (100%) | 24 (100%) | 45 (100%) | ns |

| Phase III | 13 (93%) | 22 (92%) | 42 (93%) | ns |

| Interdisciplinary team | ||||

| Medical director | 14 (100%) | 24 (100%) | 45 (100%) | |

| Cardiologist | 14 (100%) | 24 (100%) | 45 (100%) | ns |

| Rehabilitation doctor | 2 (14%) | 4 (16%) | 12 (27%) | ns |

| Physiotherapist | 7 (50%) | 20 (83%) | 44 (98%) | ns |

| Nutritionist | 11 (78%) | 19 (79%) | 40 (89%) | ns |

| Nursing | 10 (71%) | 19 (79%) | 40 (89%) | ns |

| Psychologist/psychiatrist | 4 (29%) | 17 (71%) | 36 (80%) | ns |

| Social worker | 4 (29%) | 7 (29%) | 12 (27%) | ns |

| Pulmonologist | - | - | 15 (33%) | |

| Other specialists | 4 (29%) | 18 (75%) | 21 (47%) | ns |

| Various activities of the units included | ||||

| Research | 6 (43%) | 5 (20.8%) | 19 (42%) | ns |

| Homer care | 11 (79%) | 19 (79%) | 27 (60%) | ns |

| Risk factors control | 14 (100%) | 24 (100%) | 45 (100%) | ns |

| Risk stratification | 14 (100%) | 23 (96%) | 45 (100%) | ns |

| Prescribed exercise | 14 (100%) | 24 (100%) | 45 (100%) | ns |

| Talks | 14 (100%) | 21 (88%) | 35 (78%) | 0.01 |

| Anti-smoking clinic | 10 (71%) | 9 (38%) | 12 (27%) | ns |

| Tele-rehabilitation | - | - | 14 (31%) |

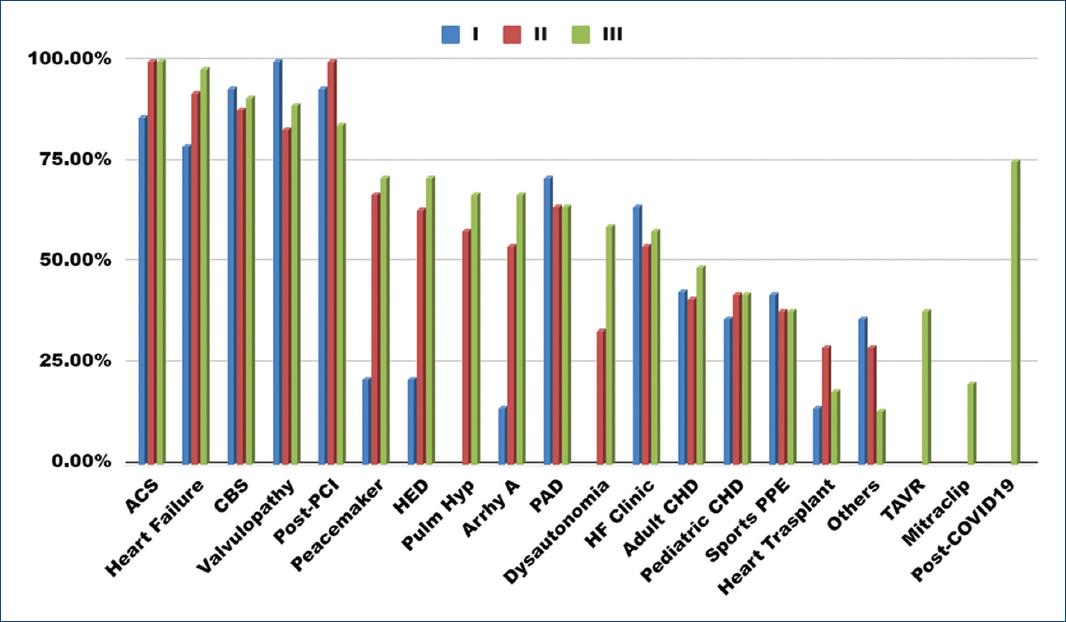

Every center (100%) realizes an initial clinical history, CV risk factors identification, CV risk stratification, and exercise training prescription and planning. After ongoing CV risk stratification, 57% of patients were reported at high risk, 27% at intermediate risk, and 16% at low risk. Figure 4 shows the most prevalent heart diseases in CR centers.

Figure 4 Most frequent diseases diagnosed in CR centers in Mexico (three registries of RENAPREC).ACS: acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CBS: coronary bypass surgery; Pulm Hyp: pulmonary hypertension; Arrhy A: arrhythmias ablation; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; and HF: heart failure. CHD: congenital heart disease; PPE: pre-participation evaluation; TAVR: transcuaneo.

The number of patients included per center is highly variable, depending on: the level of care, type of institution, private or public care, regional location, time since opening, and capacity of each center. Median patient admissions per year to CR centers are 47, from 3 to 1200 patients, where public centers receive the greatest number of patients (median of five patients/week).

Most of the CR centers (96%, n = 43) evaluated non-aerobic physical qualities, 75% (n = 33) estimated the risk of falls (many of them by Tinetti or Downton), and 38% (n = 17) carry out a preliminary sports participation evaluation. Within the transdisciplinary actions, 96% (n = 43) of the centers provided nutritional counseling to their patients, and 89% (n = 40) included psychological therapy (cognitive behavior intervention is the most frequent, 80%). Given the educational and comprehensive nature of CR programs worldwide, intervention through informative talks occurred in 78%, 66.6% received family support strategies, and 27% had some anti-smoking care or clinic.

Regarding to previous registries: 71% (n = 32) already carried out Phase I, 100% brought out the Phase II intervention, and 93% (n = 42) of the centers followed up on Phase III. There are various alternative modalities to attend patient's needs, one center reported that its main activity is the modification and control of CV risk factors and 31% (n = 14) have developed telerehabilitation strategies. Table 3 summarizes the different exercise-based interventions in the registered centers. We found, in the analysis the registry of patients who received Phase I, that the number of days average to receive rehabilitation from hospital admission is 3.2 ± 2 days. The admission time from hospital discharge to the beginning of Phase II program is 19 ± 11 days, and the average attendance rate among the registered centers is 81 ± 23%, with a dropout rate of 14%. Table 4 shows the significant difference in the admission time to Phase II from hospital discharge, in the evolution of these 13 years from the first to our third RENAPREC. Table 5 shows the most common causes of desertion.

Table 3 Characteristics of training in our registered centers

| Intervention | % | n | Intervention | % | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic endurance training | Strength and non-aerobic training | ||||

| Type and modality | Type and modality | ||||

| In devices | 95.5 | 43 | Concurrent | 91.1 | 41 |

| Continuous moderate | 95.5 | 43 | Elasticity and coordination | 93.3 | 42 |

| High-intensity interval training | 84.4 | 38 | Characteristics and instruments | ||

| Cycle ergometry | 95.5 | 43 | Isometric | 84.4 | 38 |

| Treadmill | 93.3 | 42 | Isokinetic | 2.2 | 1 |

| Arm ergometer | 55.5 | 25 | Isotonic | 97.7 | 44 |

| Hike | 53.3 | 24 | Gym | 42.2 | 19 |

| Dance | 22.2 | 10 | Suspenders | 84.4 | 38 |

| Training intensity and volume | Dumbbells | 86.6 | 39 | ||

| Target heart rate by Karvonen | 93.3 | 42 | Leggings | 11.1 | 5 |

| Target heart rate by Narita | 24.4 | 11 | Circuits | 53.3 | 24 |

| Target heart rate by Blackburn | 22.2 | 10 | Walking stick | 8.8 | 4 |

| Ventilatory thresholds | 4.4 | 2 | |||

| Perception of exertion | 93.3 | 42 | Other modalities | ||

| Dyspnea threshold | 57.7 | 26 | Claudication | 71.1 | 32 |

| Burden | 4.4 | 2 | Orthostatic challenge | 53.3 | 24 |

| Double product | 2.2 | 1 | Inspiratory | 53.3 | 24 |

| Volume calculation | 22.2 | 10 | Domiciliary | 57.7 | 26 |

Table 4 Analysis of the times of entry to Phase I and II of CR (RENAPREC I, II, and III)

| Days of admission and entry | Median | Minimum | Maximum | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I admission time | ||||

| RENAPREC I | 2 | 1 | 4 | ns |

| RENAPREC II | 3 | 1 | 5 | |

| RENAPREC III | 3 | 0 | 15 | |

| Entry time to Phase II | ||||

| RENAPREC I | 30 | 7 | 90 | < 0.05 between groups |

| RENAPREC II | 30 | 2 | 90 | |

| RENAPREC III | 20 | 2 | 50 |

Table 5 Mentions of the centers included the most common causes of desertion

| Cause of desertion | Number of mentions | Cause of desertion | Number of mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | 28 | Fear (pandemic or complications) | 3 |

| Distance and transfers | 12 | Comorbidities | 3 |

| Job occupation | 8 | Disinterest | 2 |

| Lack of network support | 6 | Resistance to change | 2 |

| Time and schedules | 5 | Family obligations | 2 |

The intervention based on exercise during Phase II is the guiding axis of the programs; it's prescription and execution are usually heterogeneous depending on: the type of center, training structure, operation-administration, volume quantification strategies, and the specialists involved in the exercise process. The frequency of exercise (particularly aerobic) varies from 3 sessions per week in hybrid programs, to 5 sessions per week in strictly supervised programs. Both programs included strength training, kinesiotherapy, or biomotor qualities. The CR program extension varied, in the most concentrated phase from 2 to the extended phase up to 36 weeks (average 4-6 weeks).

Regarding the session's safety measures, 89% (n = 40) of the registered centers have cardiopulmonary resuscitation equipment, 84% (n = 38) reported qualified personnel, and 56% (n = 25) carried out medical emergencies. Once the program is finished, 93.3% of the centers carried out and provided a medical report to both, patient and the treating doctor who refers them, and 82.2% maintain communication through social networks and by telephone, with Phase III patients for their follow-up, which has been reported at 1, 3, 6, 12, and up to 36 months (even in 11.1% of the cases, it is indefinite), but the average is between 3 and 6 months.

During the COVID19 pandemic, 37.8% of the centers (n = 17) temporarily closed their doors, of which only one remains closed due to multiple circumstances. Closing time presented a median of 4.5 months, with a minimum of 2 months and a maximum of 36 months. During this closure period, it was reported that some patients were referred to other units, others were followed up through telephone or telerehabilitation, and the others were lost to follow-up. The centers that remained open, implemented changes in structure, logistics, and sanitary measures. Furthermore, the CR units incorporated respiratory therapy for managing pulmonary and extrapulmonary COVID's sequelae. Care for post-COVID patients was reported by 73.3% (n = 33).

Health promotion and secondary prevention in the included centers

Many of the registry centers (89%, n = 40) have some detecting CV risk factors system with specific prevention strategies, and 73% (n = 33) manage health promotion in children. Some of the most common prevention strategies among the surveyed centers are conferences, social networks, press media, and some other marketing strategies. In risk factors control, 100% of the centers measured total cholesterol levels, LDL-c, HDL-c fractions, triglycerides, and serum glucose levels in their patients, and 82% (n = 37) measured levels of C-reactive protein. Al of the CR registered centers (100%) measured weight, height, body mass index, and abdominal perimeter, but the impedance and skinfold measurements strategies for determining body composition are presented in 67% and 33%, respectively.

Clinical practice guidelines allow health professionals to be guided in developing strategies for treating patients with heart disease. Most of registered centers (95%) use the guidelines of the American and European Cardiological Societies (ACC, AHA, ESC), the AACVPR guidelines, Official Mexican Standards, institutional guides, national and Ibero-American consensus, and some other specific texts for the management of various heart diseases.

Management and economic management activities of the CR centers included

The costs of care in CR units varied depending on whether it was public or private care. In 24% of the centers payment was made by the hospital institution, 16% by social security, in 22% of the cases through mixed systems and in 38% of them was assumed directly by the patient, despite that private medical insurance has a coverage of 56%. In general terms, the average cost of an interdisciplinary CR program is $1,291.94 ± 443.55 U.S. dollars; however, it varies depending on the program duration, number of sessions and services offered, and even the region where the center is located.

Teaching and research activities of CR centers in Mexico

Several of the participating centers have both, undergraduate and postgraduate teaching activities in different disciplines of medical work, such as nutrition, psychology, physiotherapy, postgraduate degrees in cardiology, rehabilitation medicine, and sports medicine; all of them also as rotations and social service, within the general curriculum for each area (11%, n = 5). However, regarding the training of health resources for CR with university endorsement, there are three centers with educational programs aimed for training high specialty in CR and a diploma in CR aimed to physiotherapists. This forming units are National Institute of Cardiology "Ignacio Chávez" with formal training for cardiologists and physiotherapists, the National Rehabilitation Institute "Guillermo Ibarra Ibarra" for rehabilitation doctors, and the National Medical Center "20 de Noviembre" for cardiologists and rehabilitation doctors.

Only 47% of the centers (n = 21) have research and publications, both in medical journals and free papers presented at national and international conferences. These lines of research are as follows: benefits of exercise-based CR in men and women, also in chronic ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, post-COVID, post-TAVR, dysautonomia, cardiometabolic disease, cardio-oncology and peri-heart transplant patients, patients with disabilities and comorbidities, conventional and cardiopulmonary exercise testing, exercise physiology, CV risk stratification, and post-COVID syndrome. Those centers that are in a hospital have an Ethics Committee (n = 7), frequently associated with the Investigation Committee.

Discussion

RENAPREC III-2022 is the third national register of cardiovascular rehabilitation and prevention centers in Mexico. Although difficulties have arisen including the COVID19 pandemic, it should be noted that over the past 13 years since the national registries began, there has been sustained growth in CR programs and units. In this census, we can see how the main aspects of development of CR, in Mexico, are represented by a greater quantity of centers that offer its services, since the first records in 199314,15 centers in 2009 and 45 centers in 2022. Many of these new units are located in the interior of the Mexican Republic, which has contributed to the decentralization of the CR. Something striking is that the growth of the centers has been a private initiative and the number of publicly funded centers has remained the same13. That is a limitation due to the importance of the public sector in health coverage in our country. In the international literature, most programs were publicly funded, especially in Europe and Central Asia through a national health service, while in the rest of the world private systems may play a more important role (United States, Middle East and North Africa)15.

On the other hand, units have greater number of services offered in an integral way, and more types of pathologies treated. As expected, the main pathology treated corresponds to ischemic heart disease. Although pathologies such as heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, dysautonomia, congenital heart disease, and cardiac implantable electronic device, among others, were also reported, like what has been published in other countries16. The median reference rate has grown from 4.4% to 9% between 2015 and 2022 registries, with a significant decrease in waiting times for the admission of Phase II patients.

Assistance activity is reported more complete, despite its heterogeneity, with an increase in Phase I offer, from 35 to 71% in 13 years, and with a good rate of maintenance of Phases II and III, but patient education through talks and workshops has decreased. The professionalization of the programs has improved with an increase in personnel with training in CR, especially cardiologists, rehabilitation doctors, and physiotherapists. However, the percentage of physicians who serve as Director of each unit, with current certification by the corresponding Mexican Council, either the Mexican Council of Cardiology and the Mexican Council of Rehabilitation Medicine, is around 60%. Similarly, the certification of the centers, by the official body SOMECCOR, which standardizes CR activities in Mexico, has been a progressive process since 20191 and has involved a greater number of centers (31%). Interdisciplinary teams also include a higher percentage of specialists in physiotherapy, nutrition, nursing, and psychology, and pulmonologists have been incorporated in a third of the centers in this registry.

There has been a growing coverage of insurance companies for CRP programs and the number of fees has been homogenized without substantial increases in minimums and maximums compared to the record of 7 years ago, for the majority, the cost of the program continues to represent the main limitation to complete them, among other reasons, such as distance, lack of family, and work support, similar to the barriers reported in the literature17.

Regarding the quality standards suggested by the International Council on Cardiac Rehabilitation (ICCPR-CRFC)18, based on the recommendations of the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, and American Association of CV Prevention and Rehabilitation, most centers comply with the control of risk factors, CV risk stratification, and supervision of physical training. At present, there are fewer anti-tobacco control clinics, that represents an area of opportunity for improvement. Another of the quality standards is represented by safety during training sessions and having personnel trained in emergency care and the necessary equipment to attend to them. There is still concern about the existence of some centers that do not meet the essential requirement of medical emergency care through a protocol resuscitation to arrest or with a defibrillator.

Although the research process aimed to solving problems, with its impact on patient care, has grown in proportional correlation to the absolute percentage of registered centers, there is still a lack of presence at this level and in the teaching field that allows us to further develop our centers' work in the face of national and international demands.

The use of telemedicine has become more frequent, to be able to provide CR care to more patients. However, there are still issues regarding the legislation, the management of potential complications, and having the necessary technology, means that this work methodology is not fully extended. In Mexico, telehealth and telemedicine are concepts that have been in the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States since 2013 and were contained in the Official Mexican Standard Proy-NOM-036-SSA3-2015, which has already been canceled. It is necessary to continue paying attention to legislation and responsibilities during remote patient care in case of omissions or complications that could arise from patients.

Initiatives have been developed at the national level, such as Infarction-Code, mentioned in RENAPREC II-2015, which plan patient care from the index event to cardiovascular rehabilitation, with the aim of improving the coverage of programs and the prognosis of patients to short and long term. Teamwork and consciousness of our processes must be promoted for successful results and desired growth of the Mexican CR in the future.

Conclusions

Since the beginning of its existence in 1944, CR in Mexico has had maturity and professionalization in its care, with accelerated growth in the past 7 years. The programs in our country continue with strengths such as interdisciplinarity, scientific and adequate preparation of specialists, national growth and diversification, and an official body that are consolidated over time. However, despite a growth in its reference rate, there are still barriers and fundamental causes of dropout, as well as heterogeneity in specific processes that are future challenges of standardization in our interventions based on exercise and education. In future registries, we hope to quantify results on the outcomes of our patients in the medium and long term.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)