Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Archivos de cardiología de México

On-line version ISSN 1665-1731Print version ISSN 1405-9940

Arch. Cardiol. Méx. vol.89 n.1 Ciudad de México Jan./Mar. 2019 Epub Oct 15, 2019

https://doi.org/10.24875/acm.m19000012

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with severe aortic stenosis for the Peruvian Social Security

1Department of Clinical Cardiology, Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular (INCOR), EsSalud

2Clinical Practice Guidelines, Drug Safety Monitoring and Techno-surveillance Directorate, Institute for Health Technologies Evaluation and Research, EsSalud

3Interventional Cardiology Department, INCOR, EsSalud

4Research Unit for the Generation and Synthesis of Evidence in Health, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola. Lima

5Faculty of Human Medicine, Universidad San Martín de Porres, Chiclayo

6Department of Cardiovascular Surgery. INCOR, EsSalud. Lima, Peru

7Department of Non-Interventional Cardiology. INCOR, EsSalud. Lima, Peru

8Institutional Directorate. INCOR, EsSalud. Lima, Peru

9Department of Diagnosis and Treatment Aid. INCOR, EsSalud. Lima, Peru

Introduction:

This article summarizes the clinical practice guide (CPG) for the evaluation and management of patients with severe aortic stenosis in the Social Security of Peru (EsSalud).

Objective:

To provide clinical evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and management of patients with severe aortic stenosis in the EsSalud.

Methods:

A local guideline development group (local GDG) was established, including medical specialists and methodologists. The local GDG formulated 7 clinical questions to be answered by this CPG. Systematic searches of systematic reviews and, when it was considered pertinent, primary studies, were conducted in PubMed during 2018. The evidence to answer each of the posed clinical questions was selected. The quality of the evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology. In periodic work meetings, the local GDG used the GRADE methodology to review the evidence and formulate the recommendations, points of good clinical practice, and the flowchart of evaluation and management. Finally, the CPG was approved with Resolution N.° 47 — IETSI — ESSALUD — 2018.

Results:

This CPG addressed 7 clinical questions regarding two issues: the initial evaluation and the management of severe aortic stenosis. Based on these questions, 9 recommendations (1 strong recommendation and 8 weak recommendations), 16 points of good clinical practice, and 1 flowchart were formulated.

Conclusion:

This article summarizes the methodology and evidence-based conclusions from the CPG for the evaluation and management of patients with severe aortic stenosis in the EsSalud.

Key words Severe aortic stenosis; Clinical practice guideline; GRADE; Evidence-based medicine; Peru

Introducción:

El presente artículo resume la guía de práctica clínica (GPC) para la evaluación y el tratamiento de pacientes con estenosis aórtica severa en el Seguro Social del Perú (EsSalud).

Objetivo:

Proveer recomendaciones para la evaluación y el tratamiento de pacientes con estenosis aórtica severa en el EsSalud basadas en evidencia científica.

Métodos:

Se conformó un grupo elaborador local (GEG-Local) que incluyó médicos especialistas y metodólogos. El GEG-Local formuló siete preguntas clínicas que ser respondidas en la presente GPC. Se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas de revisiones sistemáticas y, cuando fue considerado pertinente, estudios primarios en PubMed durante el 2018. Se seleccionó la evidencia para responder cada una de las preguntas clínicas planteadas. La calidad de la evidencia fue evaluada usando la metodología Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). En reuniones de trabajo periódicas, el GEG-Local usó la metodología GRADE para revisar la evidencia y formular las recomendaciones, los puntos de buenas prácticas clínicas y el flujograma de evaluación y tratamiento. Finalmente, la GPC fue aprobada con Resolución N.° 47 — IETSI — ESSALUD — 2018.

Resultados:

La presente GPC abordó siete preguntas clínicas, respecto a dos temas: la evaluación inicial y el tratamiento de la estenosis aórtica severa. Con base en dichas preguntas se formularon nueve recomendaciones (una recomendación fuerte y ocho recomendaciones débiles), 16 puntos de buena práctica clínica y un flujograma.

Conclusión:

El presente artículo resume la metodología y las conclusiones de la GPC para la evaluación y el tratamiento de pacientes con estenosis aórtica severa en el EsSalud.

Palabras claves: Estenosis aórtica severa; Guía de práctica clínica; GRADE; Medicina basada en evidencias; Perú

Introduction

In aortic stenosis, a decrease in the aortic valve area progressively occurs, which generates a restriction in left ventricle (LV) blood outflow to the aorta. The most common causes are degenerative, rheumatic and congenital. Degenerative aortic stenosis occurs in 5% of adults older than 65 years, out of which 11% have severe aortic stenosis. It is considered 'severe' when the aortic valve orifice is smaller than 1 cm2 and mean aortic transvalvular gradient is equal to or higher than 40 mmHg.

Patients with severe aortic stenosis are initially asymptomatic; however, in the course of the pathology they develop dyspnea, angina and syncope, which cause quality of life deterioration and increased mortality1-5. One-year risk of sudden death in asymptomatic patients is 1%, and in symptomatic individuals this risk increases to 3-5% at six months. Aortic valve replacement surgery has been shown to achieve a significant mortality reduction in these patients5-7. In patients with contraindication or high risk for aortic valve replacement surgery, percutaneous aortic valve prosthesis implantation is a safe and effective alternative.

Thus, severe aortic stenosis is a high-risk condition, which requires interdisciplinary management to reduce morbidity and mortality. The Clinical Practice Guidelines, Drug Safety Monitoring and Techno-surveillance Directorate of the Institute for Health Technologies Evaluation and Research (IETSI — Instituto de Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud e Investigación), together with specialists of the National Cardiovascular Institute (INCOR — Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular) and the Peruvian Social Security (EsSalud), developed these evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPG), which issued recommendations and good clinical practice (GCP) points for the evaluation and treatment of patients with severe aortic stenosis. The present article is a summary of said CPG.

Methodology

The procedure followed for the development of these CPGs is described in detail on its extended version, which can be downloaded from the EsSalud IETSI website (http://www.essalud.gob.pe/ietsi/guias_pract_clini.html).

In brief, the following methodology was applied:

— Formation of the local guideline development group (Local GDG). It was comprised by methodologists and cardiology, interventional cardiology and cardiovascular surgery specialist physicians.

— Formulation of questions. In accordance with this CPGs' objectives and scope, the Local GDG formulated seven clinical questions (Table 1), each one with one or more PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) questions. In turn, each PICO question could have one or more outcomes of interest.

Table 1 Addressed clinical questions

Topic Clinical questions Initial assessment Question 1. In patients with aortic stenosis, which severity classification system should be used? Treatment Question 2: In patients with severe aortic stenosis, which surgical risk graduation system should be used: STS or EuroSCORE II? Question 3: In patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, should valve replacement be early performed or wait for the patient to develop symptoms? Question 4: In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, should SAVR or TAVR be performed? Question 5: In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing TAVR is decided, which should be the first-choice access route for TAVR? Question 6: In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing TAVR is decided and who, in addition, have severe coronary artery disease, should PCI be performed? Question 7: Should a Heart Team be formed that decides the treatment of patients with severe aortic stenosis? EuroSCORE II: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score; TAVR transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

— Search and selection of evidence. For each PICO question, evidence was searched and selected. For this, during January-February 2018, a search was made for systematic reviews (SR) published as scientific articles (through systematic searches in PubMed) or performed as part of a previous CPG document (through a systematic search of CPGs on the subject) (Appendix 1). When SRs of acceptable quality were found, one was chosen for decision making, which was updated when the local GDG considered it necessary. When no RS of acceptable quality was found, a new search was made for primary studies.

— Quality of evidence evaluation. Quality of evidence for each outcome of each PICO question was considered high, moderate, low or very low (Table 2). To assess the quality of evidence, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology was followed8 and GRADE evidence profile tables were used (Appendix 2). Finally, the PICO question was assigned the lowest level of quality reached by any of these outcomes.

Table 2 Meaning of the levels of quality of evidence and strength of recommendation

Meaning Quality of evidence (⊕⊕⊕⊕) High The true effect is highly likely to be similar to the estimated effect (⊕⊕⊕○) Moderate The true effect is moderately likely to be similar to the estimated effect, but it is possible for it to be substantially different (⊕⊕○○) Low Our confidence in the estimated effect is limited. The true effect might be substantially different from the estimated effect (⊕○○○) Very low We have very little confidence in the estimated effect. The true effect is highly likely to be substantially different from the estimated effect Implication of the strength of recommendation Strong recommendation (for or against) The local GDG believes that all or nearly all professionals that review available evidence would follow this recommendation. In the recommendation formulation, the term 'recommended' is used Weak recommendation (for or against) The local GDG believes that most professionals that review available evidence would follow this recommendation, but a group of professionals might not follow it. In the recommendation formulation, the term 'suggested' is used. Local GDG: Local guideline developing group.

— Formulation of recommendations. The local GDG reviewed the selected evidence for each clinical question in periodic meetings and issued strong or weak recommendations (Table 2) using the GRADE methodology9. For this, the following was considered: 1) benefits and harms of the options; 2) patient values and preferences; 3) acceptability by health professionals; 4) feasibility of the options at EsSalud health establishments, and 5) use of resources. After discussing these criteria for each question, the local GDG formulated recommendations by consensus or by simple majority. In addition, the local GDG formulated GCP points, usually based on clinical experience.

— Review by external experts. The present CPGs were reviewed in meetings with specialist physician representatives of other institutions and decision-makers. Furthermore, the extended version was electronically submitted to external experts (mentioned in the acknowledgments section) for its review. The local GDG took the results of these reviews into account for amending the final recommendations.

— CPG approval. These CPGs were approved to be uses in EsSalud, with Resolution No. 47 - IETSI - ESSALUD - 2018.

— CPG updating. This GPC has a validity of three years. As the end of this period approaches, a literature SR will be carried out for its update, after which it will be decided whether this CPG is updated or if a new version is created.

Recommendations

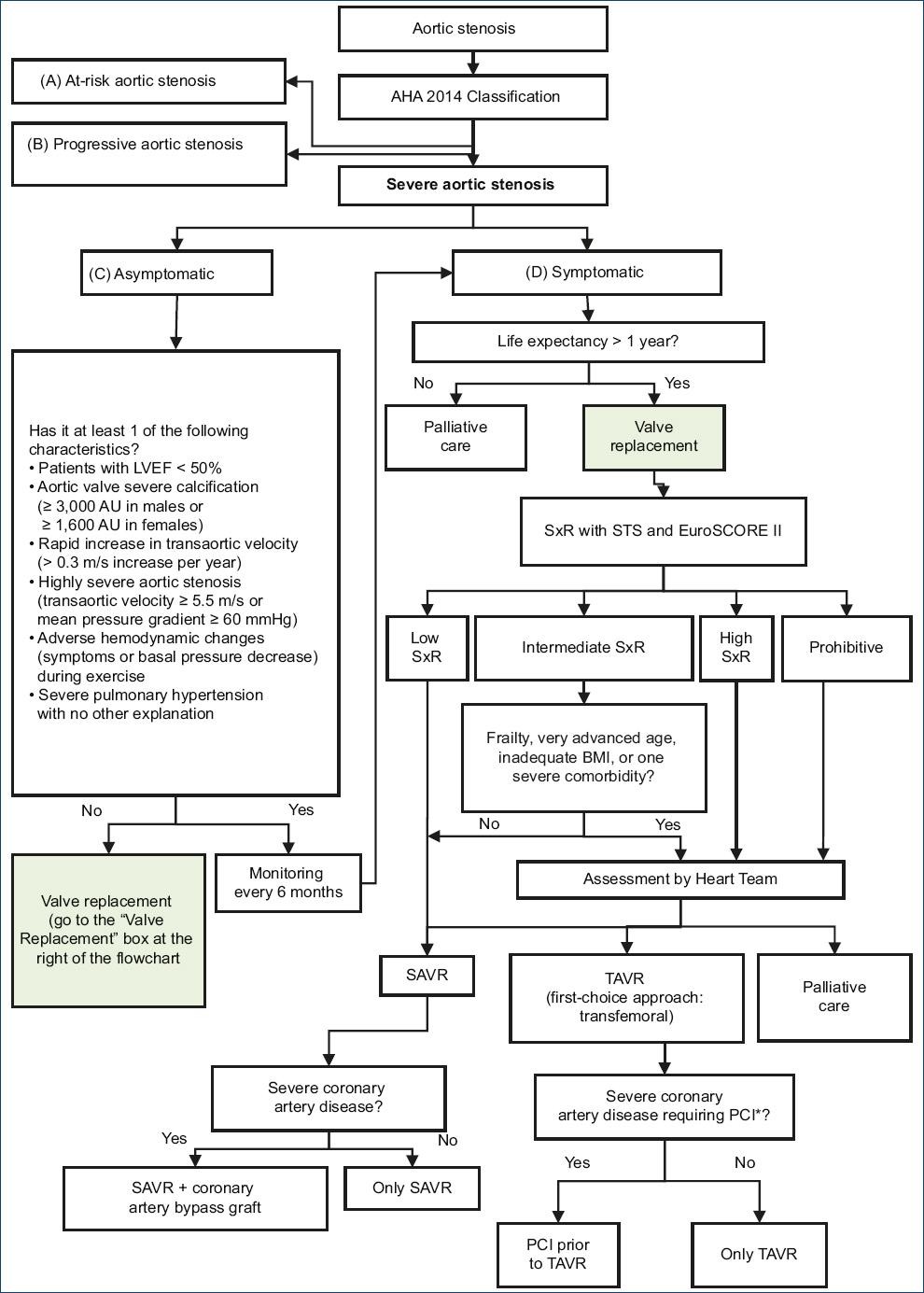

The present CPG addressed seven clinical questions, related to two subjects: severe aortic stenosis initial evaluation and treatment. Based on these questions, nine recommendations were formulated (one strong recommendation and eight weak recommendations), 16 good clinical practice points and a flow chart (Table 3 and Fig. 1).

Table 3 Full list of recommendations

| Question N° | Statement | Type* | Strength and direction† | Quality of evidence† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial assessment | ||||

| 1 | To classify patients diagnosed with aortic stenosis in mild, moderate or severe aortic stenosis, using the aortic stenosis classification system proposed by the 2014 AHA/ACC guidelines (not modified in AHA/ACC 2017 update) is recommended. | GCP | ||

| Treatment | ||||

| 2 | In patients with severe aortic stenosis with SAVR or TAVR indication, we suggest applying the EuroSCORE II and STS scoring systems to assess valve replacement surgical risk. | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊝⊝⊝) |

| Patients with severe aortic stenosis shall be classified according to their surgical risk as: — Low risk. STS or EuroSCORE II < 4%, without frailty or comorbidities and with no hindrances for the specific procedure — Intermediate risk. STS or EuroSCORE II between 4 and 8%, with no more than slight frailty or compromise of no more than one major organ/system that will not improve postoperatively, and minimum hindrances for the specific procedure — High risk. STS or EuroSCORE II > 8%, or with moderate to severe frailty, with compromise of no more than 2 major organs/systems that will not improve postoperatively, or a possible hindrance to the specific procedure — Prohibitive risk. Preoperative one-year mortality and morbidity risk > 50%, with compromise of ≥ 3 major organs/systems that will not improve postoperatively, severe frailty, or a severe hindrance to the specific procedure |

GCP | |||

| 3 | In patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, we suggest not systematically performing early aortic valve replacement. | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊝⊝⊝) |

| Patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis shall be scheduled for early valve replacement if they have any of the following conditions: — Patients with LVEF < 50% — Aortic valve severe calcification (≥ 3,000 AU in males or ≥ 1,600 AU in females) — Rapid increase in transaortic velocity (> 0.3 m/s increase per year) — Highly severe aortic stenosis (transaortic velocity ≥ 5.5 m/s or mean gradient pressure ≥ 60 mmHg) — Adverse hemodynamic changes (symptoms or decrease in blood pressure) during stress test — Severe pulmonary hypertension with no other explanation |

GCP | |||

| Patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis should be clinically assessed every 6 months or when the patient exhibits disease-related symptoms (dyspnea, angina or syncope). | GCP | |||

| Patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis who start developing symptoms shall be assessed for risk stratification and aortic valve replacement scheduling | GCP | |||

| 4 | In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year, aortic valve replacement should be performed | GCP | ||

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and low surgical risk, we suggest SAVR performance as first treatment choice | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊝⊝⊝) | |

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and intermediate surgical risk, we suggest SAVR performance as first treatment option | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊕⊕⊝) | |

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and high surgical risk, we suggest the performance of SAVR or TAVR | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊝⊝⊕⊝) | |

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year that are classified as inoperable we suggest the performance of TAVR as first treatment option | R | Strong in favor | Moderate (⊕⊝⊝⊝) | |

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and low surgical risk, consider SAVR as first-choice treatment, without the need for prior evaluation by the Heart Team | GCP | |||

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and who have intermediate surgical risk (who in addition have criteria of frailty, very advanced age, inadequate body mass index or a severe comorbidity), high surgical risk, or who are considered inoperable: have an evaluation made by the Heart Team to decide their treatment | GCP | |||

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, in situations of emergency, acute decompensation or non-cardiac surgery, and who have valve replacement indication: consider percutaneous valvotomy as bridging therapy for SAVR or TAVR | GPC | |||

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who have a life expectancy of less than one year, contraindicate SAVR and TAVR and provide palliative treatment | GPC | |||

| In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR, follow the procedures established by procedural guidelines or local protocols | GPC | |||

| Disagreements on risk stratification or treatment will be decided by the Heart Team | GPC | |||

| 5 | In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing TAVR is decided, we recommend the first choice approach to be transfemoral | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊝⊝⊝) |

| When the transfemoral route is not possible, the Heart Team will evaluate each particular case to define the possible use of other access routes, such as through the subclavian artery or the transapical or transaortic routes. The Heart Team will make this decision based on invasive and/or non-invasive imaging studies | GPC | |||

| 6 | In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom the performance of TAVR is decided, and who in addition have severe coronary artery disease, we suggest the performance of PCI | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊝⊝⊝) |

| In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom the performance of TAVR is decided, and who in addition have severe coronary artery disease for which PCI has been decided, we suggest for PCI to be carried out prior to TAVR | R | Weak in favor | Very low (⊕⊝⊝⊝) | |

| Perform myocardial revascularization (PCI for those undergoing TAVR or coronary artery bypass graft for those undergoing SAVR) when severe coronary artery disease is found (≥ 70% reduction in the diameter of any major coronary artery or ≥ 50% reduction in the diameter of the left coronary artery trunk) | GPC | |||

| 7 | Health facilities that perform cardiovascular surgery in patients with severe aortic stenosis with intermediate, high and/or prohibitive surgical risk shall put together a Heart Team that will be in charge of deciding patient treatment | GCP | ||

| The Heart Team should be made up of at least: — One clinical cardiologist with experience in valvular pathology — One cardiologist expert in cardiovascular imaging — One interventional cardiologist — One cardiovascular surgeon with experience in valvular pathology |

GCP | |||

EuroSCORE II: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; LVEF: Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score; TAVR: transcathether aortic valve replacement.

*Recommendation (R) or good clinical practice (GPC) point.

†Strength, direction and quality of evidence are only established for recommendations, not for GCP points.

Figure 1 Severe aortic stenosis evaluation and treatment flow chart. AHA: American Heart Association; EuroSCORE II: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; LVEF: left ventricle ejection fraction; BMI: body mass index; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SxR: surgical risk; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score; TAVR: transthoracic aortic valve replacement.*Severe coronary disease: ≥ 70% reduction in the diameter of any major coronary artery, or ≥ 50% reduction in the diameter of the left coronary artery trunk.

In patients with aortic stenosis, the physician should decide which criteria will be used to establish the severe aortic stenosis diagnosis (question 1). Then, the physician should decide on treatment, and for that he/she must determine which surgical risk grading system will be used (question 2), how will he/she treat asymptomatic patients (question 3) and when will he/she choose surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in symptomatic patients (question 4). If performing a TAVR is decided, the access route must be decided (question 5) and the possibility of carrying out or not a percutaneous coronary intervention if the patient also has severe coronary artery disease (question 6). Finally, for the management of patients with severe aortic stenosis, it is necessary to determine if a group of experts or Heart Team will be required (question 7).

Below, the recommendations for each clinical question, as well as a summary of the rationale to arrive to each recommendation, are presented.

Question 1. In patients with aortic stenosis, which severity classification system should be used?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

To classify aortic stenosis-diagnosed patients into mild, moderate or severe aortic stenosis, using the aortic stenosis classification system proposed by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) 2014 guidelines (not modified in the 2017 update) is recommended. GCP.

From evidence to decision

Severity should be determined in all patients with aortic stenosis. This classification has prognostic and therapeutic implications. In patients with mild or moderate aortic stenosis, clinical observation and periodic monitoring shall be carried out. In those with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, valve replacement shall be evaluated.

Different systems have been developed to classify the severity of patients with aortic stenosis. Our systematic search found classifications in the AHA/ACC 200610 and 2014, 2017-updated CPGs11, in the European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS) 2017 CPGs12 and in the Brazilian Society of Cardiology/Inter-American Society of Cardiology (BSC/IASC Brazil) 2011 CPGs13; in addition to a classification proposed by Lancelotti14. No studies were found that have compared the different types of classification between each other. Therefore, no recommendations were issued, but GCP points.

Good clinical practice approach

By consensus, the AHA/ACC 2014 classification system was chosen11 (Table 4), since, currently, it is the most widely known and used in clinical practice and in clinical trials. The 2017 update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guidelines did not modify this classification15.

Table 4 Aortic stenosis stages according to AHA/ACC (2014)11

| Grade | Definition | Valvular anatomy | Aortic valve hemodynamic measurements | Hemodynamic consequences | Symptoms | LVEF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca++ | Mobility | Essential criteria | Additional measures | |||||

| A | At risk of AS | + | Normal | Aortic Vmax < 2 m/s | - | None | Normal | |

| B | Progressive AS | ++ | ↓a↓ | Mild AS: aortic Vmax 2.0-2.9 m/s or meanΔP < 20 mmHg Moderate AS: aortic Vmax 3.0-3.9 m/s or mean ΔP < 20-39 mmHg |

- | None | Normal | |

| C: Severe asymptomatic AS | ||||||||

| C1 | Severe asymptomatic AS | +++ | ↓↓↓ | Severe AS: aortic Vmax ≥4 m/s or meanΔP ≥ 40 mmHg Highly severe AS: aortic Vmax ≥ 5.0 m/s or mean ΔP ≥ 60 mmHg |

AVA ≤ 1.0 cm2 (or AVA ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2) | — LV diastolic dysfunction — Mild LV hypertrophy |

— None — Exercise testing reasonable to confirm symptoms |

Normal |

| C2 | Severe asymptomatic AS with LV dysfunction | +++ | ↓↓↓ | Severe AS: aortic Vmax ≥ 4 m/s or mean ΔP ≥ 40 mmHg | AVA ≤ 1.0 cm2 (or AVAi ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2) | None | < 50% | |

| D: Severe symptomatic AS | ||||||||

| D1 | Severe symptomatic AS with high gradient | ++++ | ↓↓↓↓ | Aortic Vmax ≥4 m/s or meanΔP ≥ 40 mmHg | AVA ≤ 1.0 cm2 (or AVAi ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2), but it can be larger with combined AS/AI | — LV diastolic dysfunction — LV hypertrophy — PHT can be present |

— Dyspnea on exertion or exercise decreased tolerance — Exercise-induced angina — Exercise-triggered syncope or pre-syncope |

Normal or ↓ |

| D2 | Severe symptomatic AS with low flow/low gradient and reduced LVEF | ++++ | ↓↓↓↓ | AVA ≤ 1.0 cm2 with aortic Vmax <4 m/s or mean ΔP < 40 mmHg at rest | Dobutamine stress test shows an AVA ≤ 1.0 cm2 with aortic Vmax ≥4 m/s with any flow | — LV diastolic dysfunction — LV hypertrophy |

— Heart failure — Angina — Syncope or pre-syncope |

< 50% |

| D3 | Symptomatic severe AS with low gradient and normal LVEF or Symptomatic severe AS with low paradoxical flow | ++++ | ↓↓↓↓ | AVA ≤ 1.0 cm2 with aortic Vmax ≥4 m/s or mean ΔP < 40 mmHg Measured when the patient is normotensive (systolic BP < 140 mmHg) | AVAi ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2 and < 35 mL/m2 | — LV wall increased thickness — Small LV chamber — Restrictive diastolic filling |

— Heart failure — Angina — Syncope or pre-syncope |

≥ 50% |

AI; aortic insufficiency; AS: aortic stenosis; AVA: aortic valve area; AVAi: aortic valve area index; BP: blood pressure; Ca++: valve calcification; LV: left ventricle; LVEF: left ventricle ejection fraction; meanΔP: transaortic pressures mean difference; PHT: pulmonary hypertension; transaortic Vmax: maximum transaortic velocity.

Question 2. In patients with severe aortic stenosis, which surgical risk grading system score should be used: STS or EuroSCORE II?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

— In patients with severe aortic stenosis with SAVR or TAVR indication, we suggest applying the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II) score and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score (STS) to assess surgical risk for valve replacement. Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence (⊕⊝⊝⊝).

-

— Patients with severe aortic stenosis will be classified according to their surgical risk as:

Low risk. STS or EuroSCORE II < 4%, without frailty or comorbidities and with no hindrances to the specific procedure.

Intermediate risk. STS or EuroSCORE II between 4 and 8%, with no more than slight frailty or compromise of no more than one major organ/system that will not improve postoperatively and minimum hindrances to the specific procedure.

High risk. STS or EuroSCORE II > 8% or with moderate to severe frailty, with compromise of no more than two major organs/systems that will not improve postoperatively or possible hindrance to the specific procedure.

Prohibitive risk. Preoperative mortality and morbidity risk > 50% at one year, with compromise of three or more major organs/systems that will not improve postoperatively, severe frailty or severe hindrance to the specific procedure. GCP

From evidence to decision

Patients with severe aortic stenosis require aortic valve replacement treatment, and it is therefore necessary for surgical risk to be assessed in these patients. The most widespread and known surgical risk scoring systems are EuroSCORE II16 and STS17. Both predict mortality and morbidity risk after valve replacement surgery. EuroSCORE II is available at www.euroscore.org and STS at http://riskcalc.sts.org/stswebriskcalc/#/calculate

To answer this question, three subpopulations were assessed: patients intervened with SAVR, patients operated with TAVR and patients who were operated with either intervention indistinctly. SRs of observational studies for each subpopulation were found. In patients undergoing SAVR, one SR (5 studies, n = 11,791) concluded that STS overestimates mortality18. In patients undergoing TAVR, one SR (24 studies, n = 12,346) concluded that EuroSCORE II underestimates mortality19. In patients undergoing SAVR or TAVR, one SR (10 studies, n = 13,856) concluded that STS overestimates mortality18.

Owing to these heterogeneous results, making a recommendation in favor of applying both scoring systems for making the decision on which intervention to perform was decided. Given that the quality of evidence is very low and that not all doctors would accept such a measure, and neither would patients do, since it would imply a larger number of evaluations and time, assigning a weak strength of recommendation was decided.

Good clinical practice approach

Using the cutoff points proposed by the Singh meta-analysis (2017)20 and the ESC/EACTS 201712 guidelines was decided to classify patients with severe aortic stenosis at low risk (< 4%), intermediate risk (4-8%) and high risk (> 8%), both with STS and with EuroSCORE II21,22. Finally, adopting the consensus recommendation of the ACC23 experts was decided in order to include other criteria such as frailty, comorbidities and hindrances to the specific procedure.

Question 3. In patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, should aortic valve replacement be early performed or wait for the patient to develop symptoms?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

— In patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, we suggest not systematically performing early aortic valve replacement. Weak recommendation against, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

-

— Patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis shall be scheduled for early valve replacement if they have any of the following conditions:

Patients with left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%.

Aortic valve severe calcification (≥ 3,000 Agatston units [AU] in men or ≥ 1,600 AU in women.

Rapid increase in transaortic valve velocity (> 0.3 m/s increase per year).

Highly severe aortic stenosis (transaortic velocity ≥ 5.5 m/s or mean pressure gradient ≥ 60 mmHg).

Adverse hemodynamic changes (symptoms or blood pressure decrease) during stress testing.

Severe pulmonary hypertension with no other explanation. GCP.

— Patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis should be clinically evaluated every six months or when the patient experiences symptoms related to the disease (dyspnea, angina or syncope). GCP.

— Patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis that start developing symptoms will be assessed for risk stratification and aortic valve replacement scheduling. GCP.

From evidence to decision

A patient with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis is defined as a patient who does not report symptoms24. Approximately more than half the patients with severe aortic stenosis are asymptomatic at diagnosis6. Treatment of these patients is controversial.

One SR25 (4 observational studies, n = 1,300) compared early aortic valve replacement versus conservative treatment and reported similar all-cause mortality or cardiovascular cause mortality. This would indicate that the short-term benefit of performing early interventions in this group of patients is probably small. However, the lack of randomized clinical trials (RCTs)26 hinders clearly establishing the potential benefit of early intervention.

A potential benefit of early intervention could be the delay in symptom onset and the possibility of definitive treatment in patients who cannot return for consultation. In our institution, availability of surgery shifts for aortic valve replacement is limited, and this intervention should therefore be carried out in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, since they are at higher mortality risk than those who are asymptomatic. Therefore, formulating a recommendation against systematically practicing early aortic valve replacement was decided. Given that the quality of evidence is very low, that patient acceptability is low because they are asymptomatic, that few physicians would agree to precociously carry out the procedure and that feasibility is therefore low, assigning a weak strength of recommendation was decided.

Good clinical practice approach

Based on two CPGs recommendations11,12, some subgroups of asymptomatic patients may be considered for early aortic valve replacement, due to the increased risk of mortality. Furthermore, consensus was reached on that patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis should be evaluated every six months or when they experience symptoms related to the disease. In addition, it was deemed that when these patients develop symptoms, they should undergo valve replacement intervention.

Question 4. In patients with severe symptomatic stenosis aortic, should surgical aortic valve replacement or percutaneous aortic valve replacement be performed?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year, aortic valve replacement should be performed. GCP.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and low surgical risk, we suggest the performance of SAVR as the first treatment option. Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and intermediate surgical risk, we suggest the performance of SAVR as first treatment option. Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and high surgical risk, we suggest the performance of SAVR or TAVR. Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than a year and who are classified as inoperable, we suggest the performance of TAVR as first treatment option. Strong recommendation in favor, moderate quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and low surgical risk, SAVR should be considered as first treatment choice, without the need of previous assessment by the Heart Team. GCP.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more than one year and who have intermediate surgical risk (and who also have frailty criteria, very advanced age, inadequate body mass index or a severe comorbidity), high surgical risk or who are considered inoperable: assessment by the Heart Team should be performed to decide their treatment. GCP.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, in emergency situations, acute decompensation or non-cardiac surgery and who have valve replacement indication: consider performing percutaneous valvotomy as bridge therapy for SAVR or TAVR. GCP.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who have a life expectancy of less than one year, contraindicate SAVR and TAVR and provide palliative treatment. GCP.

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR, follow the procedures established in procedural guidelines or local protocols. GCP.

— Disagreements in risk stratification or treatment will be decided by the Heart Team. GCP.

From evidence to decision

This question addresses the management of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. In these patients, SAVR or TAVR should be performed.

For this question, the following subpopulations were assessed: patients with low, intermediate and high surgical risk and inoperable patients. A patient is defined at low, intermediate and high surgical risk when he/she obtains values < 4, 4-8 and > 8%, respectively, on any of the proposed indexes (EuroSCORE II or STS)12,20,27. An inoperable patient is defined as that who has a preoperative mortality and morbidity risk > 50% at one year, with compromise of ≥ 3 major organs/systems that will not improve postoperatively, severe frailty or a severe hindrance to the specific procedure28.

In patients with low surgical risk, one SR29 (2 RCTs and 4 observational studies, n = 3,484) found that TAVR, in comparison with SAVR, has similar all-cause 30 days and 1-year mortality, higher late mortality, lower risk of acute kidney injury, similar risk of stroke, higher risk for major vascular complications and need for permanent pacemaker implantation. Based on these heterogeneous results, and since TAVR was deemed to require greater use of resources, formulating a recommendation in favor of SAVR was decided. Given that the quality of evidence is low, and that patients and doctors do not entirely accept it, this recommendation had a weak strength.

In patients with intermediate surgical risk, the SRs by Singh20 (3 RCTs and 5 observational studies, n = 4,752) and Sardar27 (2 RCTs and 5 observational studies, n = 4,601) found that TAVR, in comparison with SAVR, has similar 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality, similar stroke risk, similar myocardial infarction risk, lower acute kidney injury risk, lower major bleeding risk and greater need for permanent pacemaker implantation. Based on these heterogeneous results, in addition to the fact that the balance of benefits and risks of the intervention did not favor the use of TAVR, despite the fact that this intervention requires higher use of resources, formulating a recommendation in favor of SAVR was decided. Since the quality of evidence is low, it would not be entirely accepted by doctors and patients, which would hinder its feasibility; therefore, assigning weak strength to the recommendation was decided.

In patients with high surgical risk, the PARTNER 1 RCT (n = 699), with results published at one year30, three years31 and five years of follow-up32, TAVR, in comparison SAVR, was found to have similar all-cause mortality at 30 days, one year, three and five years, higher risk of stroke, similar risk of transient ischemic attack, lower risk of acute kidney failure, similar risk of acute myocardial infarction, higher risk of major vascular complication and lower risk of major bleeding. Since the quality of evidence was low, and since doctors and patients would prefer TAVR, but owing to its low feasibility and excessive use of resources, formulating a weak recommendation for using any of the interventions (SAVR or TAVR) was decided. In inoperable patients but with life expectancy of more than one year, there are also results available from the PARTNER 1 RCT (n = 358), published at one28, two33, three34 and five years of follow-up24; TAVR was found to have lower all-cause mortality than medical treatment. Therefore, formulating a recommendation in favor of TAVR was decided. Given that the quality of evidence was moderate and that it would be accepted by both doctors and patients, this recommendation had a strong strength of recommendation.

Good clinical practice approach

— In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with life expectancy of more one year, it was agreed that performing aortic valve replacement should be sought in order to relieve symptoms and lessen mortality. In addition, in patients with life expectancy of less than one year, carrying out SAVR or TAVR was considered not to be justified11,24,34.

— By consensus, it was established that a multidisciplinary team, or Heart Team, should decide the treatment of all patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis deemed inoperable or at high surgical risk, as well as of those with surgical intermediate risk who are also frail or have advanced age, inadequate body mass index or a severe comorbidity15.

— Aortic valvuloplasty performance was considered as a temporary treatment for some patients who have a valve replacement indication and that find themselves in emergency situations. It should be kept in mind that this treatment is effective during 6 or 12 months, since later the aortic valve develops stenosis again11,35,36.

— Finally, it was considered important to note that TAVR should be performed following procedural guidelines or local protocols and that disagreements on risk stratification or treatment should be assessed by the Heart Team.

Question 5. In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing percutaneous aortic valve replacement is decided, what should be the first-choice access route to for it?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

— In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing TAVR is decided, we recommend that first-choice access route should be transfemoral. Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— When the transfemoral route is not feasible, the Heart Team will evaluate each particular case to define the possible use of other approaches such as through the subclavian artery, or the transapical or transaortic routes. The Heart Team will make this decision based on invasive and/or non-invasive imaging studies. GCP.

From evidence to decision

Once TAVR performance has been decided, the access route for transcatheter aortic valve implantation should be established; the most common routes in our setting are: transfemoral (TF), through the subclavian artery (TSc) and transapical (TA).

To answer this question, two comparisons were assessed: TF vs. TSc and TF vs. TA. As for the comparison between TF and TSc, one SR (6 observational studies, n = 4,504) found that 30-day mortality, one-year mortality, major complications at 30 days and acute kidney injury were similar between both groups37. However, favoring the TF approach was decided because it is easier and more accepted by professionals.

Regarding the comparison between TF and TA, the SRs that were considered found that 30-day mortality38 and acute kidney injury39 were lower in the TF group, while vascular complications were higher in the TF group40; and one-year mortality40, definitive pacemaker implantation and 30-day bleeding were similar in both groups41. Thirty-day mortality and acute kidney injury were considered to be the most clinically relevant outcomes and, hence, favoring the TF approach was decided.

Therefore, due to its benefits, and especially to a lower risk of complications, formulating a recommendation in favor of the use of the TF route was decided. Given that the quality of evidence is very low, that the route of access for TAVR may depend on anatomical factors, and due to certain comorbidities, as well as to the fact that not all doctors and patients find always using this route of access acceptable, formulating a weak recommendation was decided.

Question 6. In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing percutaneous aortic valve replacement is decided and who, in addition, have severe coronary artery disease, should percutaneous coronary intervention be performed?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

— In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing TAVR is decided and who, in addition, have severe coronary artery disease, we suggest performing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— In patients with severe aortic stenosis in whom performing TAVR is decided and who, in addition, have severe coronary artery disease for which performing PCI has been decided, we suggest that PCI should be carried out prior to TAVR. Weak recommendation in favor, very low quality of evidence ⊕⊝⊝⊝.

— Performing myocardial revascularization (PCI for those undergoing TAVR or coronary artery bypass graft for those undergoing SAVR) is recommended when severe coronary artery disease is found (≥ 70% reduction in the diameter of any major coronary artery or ≥ 50% reduction in the diameter of the left coronary artery trunk). GCP.

From evidence to decision

Approximately half the patients with severe aortic stenosis have chronic coronary heart disease6. In patients who will undergo TAVR and that also have severe coronary disease, whether PCI is to be performed should be decided, and if so, whether it will be performed in advance or at the same moment (concomitant) than TAVR.

With regard to the decision to perform PCI or not, one SR (7 observational studies, n = 1,631) compared patients undergoing TAVR with PCI and undergoing TAVR without PCI, and found that 30-day, 6-month and one-year mortality, cardiovascular mortality, as well as vascular access site complications, were similar42. This evidence suggests that PCI for severe coronary disease might be carried out without major risks in these patients. Therefore, formulating a recommendation in favor of PCI performance was decided.

Regarding the decision on whether to perform PCI previously or concomitant with TAVR, one SR (7 observational studies, n = 1,631) that compared patients undergoing PCI prior and concomitant with TAVR, found that kidney failure incidence was higher in the concomitant group, whereas 30-day mortality and vascular access site complications were similar between groups42. In that same sense, an observational study (n = 65) found that mortality was similar between these groups43. Due to the lower risk of kidney failure and the complexity of performing PCI concomitant with TAVR in our context, formulating a recommendation in favor of the performance of PCI prior to TAVR was decided.

In view of the very low quality of evidence, regular acceptability by doctors and patients, and the low feasibility of performing this procedure, assigning a weak strength of recommendation was decided.

Good clinical practice approach

Adopting the AHA/ACC 2014 guidelines44 GCP point on the need for perform myocardial revascularization (PCI for those undergoing TAVR or coronary artery bypass graft for those undergoing SAVR) in those patients with severe coronary artery disease (defined as ≥ 70% reduction in the diameter of any major coronary artery or ≥ 50% reduction in the diameter of the left coronary artery trunk) was considered pertinent.

Question 7. Should a Heart Team that decides the treatment of the patient with severe aortic stenosis be put together?

Recommendations and good clinical practice points

From evidence to decision

The Heart Team is a multidisciplinary and collaborative team whose purpose is to make decisions about the treatment of patients with severe aortic stenosis with intermediate, high or prohibitive risk45,46. In the performed search no studies were found that have assessed the Heart Team efficacy, which is why no recommendations were issued, but GCP points were established by consensus.

Good clinical practice approach

It was deemed that health establishments that carry out cardiac surgery in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis and that have high surgical risk need to decide between the performance of SAVR and TAVR46 in the Heart Team. For the formation of the Heart Team, recommendations of other authors were considered15,26,46-52, as well as feasibility according to the local context. This way, it was established by consensus that the Heart Team should be comprised by at least: one clinical cardiologist with experience in valvular pathology, one cardiologist expert in cardiovascular imaging, one interventional cardiologist certified in TAVR and one cardiovascular surgeon with experience in valvular pathology.

Authorship contributions

All authors participated in the development of these guidelines. JHM, ATR, CAAR and JEFC were responsible for the systematic searches and quality assessment of the studies for each question. All authors participated in the discussion of the retrieved studies and in the formulation of recommendations and GCP points. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript final version.

Ethical responsibilities

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare having followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Revista Archivos de Cardiología de México online (http://www.desarrollo-archivoscardio.ml/index.php). These data are provided by the corresponding author and published online for the benefit of the reader. The contents of supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

REFERENCES

1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases:a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1005-11. [ Links ]

2. Otto CM, Prendergast B. Aortic-valve stenosisfrom patients at risk to severe valve obstruction. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):744-56. [ Links ]

3. Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG. Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(6):2111-5. [ Links ]

4. Pellikka PA, Nishimura RA, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. The natural history of adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(5):1012-7. [ Links ]

5. Schwarz F, Baumann P, Manthey J, Hoffmann M, Schuler G, Mehmel HC, et al. The effect of aortic valve replacement on survival. Circulation. 1982;66(5):1105-10. [ Links ]

6. Eveborn GW, Schirmer H, Heggelund G, Lunde P, Rasmussen K. The evolving epidemiology of valvular aortic stenosis. The Tromso study. Heart. 2013;99(6):396-400. [ Links ]

7. Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, Malouf JF, Bailey KR, Scott CG, et al. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation. 2005;111(24):3290-5. [ Links ]

8. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines:3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401-6. [ Links ]

9. Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines:14. Going from evidence to recommendations:the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719-25. [ Links ]

10. American College of Cardiology;American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease);Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease:a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease):developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists:endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114(5):e84-231. [ Links ]

11. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:executive summary:a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(23):e521-643. [ Links ]

12. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(36):2739-91. [ Links ]

13. Tarasoutchi F, Montera MW, Grinberg M, Barbosa MR, Piñeiro DJ, Sánchez CRM, et al. Diretriz Brasileira de Valvopatias - SBC 2011/I Diretriz Interamericana de Valvopatías - SIAC 2011. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;97(5 supl.1):1-67. [ Links ]

14. Lancellotti P, Magne J, Donal E, Davin L, O'Connor K, Rosca M, et al. Clinical outcome in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis:insights from the new proposed aortic stenosis grading classification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(3):235-43. [ Links ]

15. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Fleisher LA, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(25):e1159-95. [ Links ]

16. Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, Nilsson J, Smith C, Goldstone AR, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41(4):734-44;discussion 44-5. [ Links ]

17. O'Brien SM, Shahian DM, Filardo G, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models:part 2--isolated valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1 Suppl):S23-42. [ Links ]

18. Biancari F, Juvonen T, Onorati F, Faggian G, Heikkinen J, Airaksinen J, et al. Meta-analysis on the performance of the EuroSCORE II and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Scores in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28(6):1533-9. [ Links ]

19. Wang TKM, Wang MTM, Gamble GD, Webster M, Ruygrok PN. Performance of contemporary surgical risk scores for transcatheter aortic valve implantation:A meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017;236:350-5. [ Links ]

20. Singh K, Carson K, Rashid MK, Jayasinghe R, AlQahtani A, Dick A, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in intermediate surgical risk patients with severe aortic stenosis:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;27(2):227-34. [ Links ]

21. Ad N, Holmes SD, Patel J, Pritchard G, Shuman DJ, Halpin L. Comparison of EuroSCORE II, Original EuroSCORE, and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score in Cardiac Surgery Patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(2):573-9. [ Links ]

22. Arangalage D, Cimadevilla C, Alkhoder S, et al. Agreement between the new EuroSCORE II, the Logistic EuroSCORE and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons score:Implications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;107(6-7):353-60. [ Links ]

23. Otto CM, Kumbhani DJ, Alexander KP, Calhoon JH, Desai MY, Kaul S, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the management of adults with aortic stenosis:a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(10):1313-46. [ Links ]

24. Kapadia SR, Leon MB, Makkar RR, Tuzcu EM, Svensson LG, Kodali S, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard treatment for patients with inoperable aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1):a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2485-91. [ Links ]

25. Lim WY, Ramasamy A, Lloyd G, Bhattacharyya S. Meta-analysis of the impact of intervention vs. symptom-driven management in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Heart. 2017;103(4):268-72. [ Links ]

26. Iglesias D, Salinas P, Moreno R, García-Blas S, Calvo L, Jiménez-Valero S, et al. Prognostic impact of decisions taken by the heart team in patients evaluated for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Rev Port Cardiol. 2015;34(10):587-95. [ Links ]

27. Sardar P, Kundu A, Chatterjee S, Feldman DN, Owan T, Kakouros N, et al. Transcatheter vs. surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients:Evidence from a meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90(3):504-15. [ Links ]

28. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-607. [ Links ]

29. Witberg G, Lador A, Yahav D, Kornowski R. Transcatheter vs. surgical aortic valve replacement in patients at low surgical risk:A meta-analysis of randomized trials and propensity score matched observational studies. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 20181;92(2):408-16. [ Links ]

30. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, et al. Transcatheter vs. surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2187-98. [ Links ]

31. Deeb GM, Reardon MJ, Chetcuti S, Patel HJ, Grossman PM, Yakubov SJ, et al.;CoreValve US Clinical Investigators. 3-Year outcomes in high-risk patients who underwent surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(22):2565-74. [ Links ]

32. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, et al.;PARTNER 1 trial investigators. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1):a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2477-84. [ Links ]

33. Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, Kapadia S, Pichard AD, Douglas PS, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(18):1696-704. [ Links ]

34. Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Agarwal S, Kodali S, et al. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation. 2014;130(17):1483-92. [ Links ]

35. Brown JM, O'brien SM, Wu C, Sikora JA, Griffith BP, Gammie JS. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years:changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(1):82-90. [ Links ]

36. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, Borenstein N, Tron C, Bauer F, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis:first human case description. Circulation. 2002;106(24):3006-8. [ Links ]

37. Amat-Santos IJ, Rojas P, Gutierrez H, Vera S, Castrodeza J, Tobar J, et al. Transubclavian approach:A competitive access for transcatheter aortic valve implantation as compared to transfemoral. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92(5):935-44. [ Links ]

38. Chandrasekhar J, Hibbert B, Ruel M, Lam BK, Labinaz M, Glover C. Transfemoral vs non-transfemoral access for transcatheter aortic valve implantation:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(12):1427-38. [ Links ]

39. Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Gillaspie EA, Greason KL, Kashani KB. The risk of acute kidney injury following transapical vs. transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9(4):560-6. [ Links ]

40. Panchal HB, Ladia V, Amin P, Patel P, Veeranki SP, Albalbissi K, et al. A meta-analysis of mortality and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients undergoing transfemoral vs. transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation using edwards valve for severe aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(12):1882-90. [ Links ]

41. Ghatak A, Bavishi C, Cardoso RN, Macon C, Singh V, Badheka AO, et al. Complications and mortality in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement with Edwards SAPIEN &SAPIEN XT valves:A meta-analysis of world-wide studies and registries comparing the transapical and transfemoral accesses. J Interv Cardiol. 2015;28(3):266-78. [ Links ]

42. Bajaj A, Pancholy S, Sethi A, Rathor P. Safety and feasibility of PCI in patients undergoing TAVR:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 2017;46(2):92-9. [ Links ]

43. Griese DP, Reents W, Toth A, Kerber S, Diegeler A, Babin-Ebell J. Concomitant coronary intervention is associated with poorer early and late clinical outcomes in selected elderly patients receiving transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46(1):e1-7. [ Links ]

44. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines 2014.10;63(22):e57-185. [ Links ]

45. Decision Memo for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) (CAG-00430N) [Internet]. Baltimore:Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services; 2012 [fecha de última actualización:15/11/2018]. Disponible en:https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=257. [ Links ]

46. Sintek M, Zajarias A. Patient evaluation and selection for transcatheter aortic valve replacement:the heart team approach. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56(6):572-82. [ Links ]

47. Parma R, Zembala MO, Dabrowski M, Jagielak D, Witkowski A, Suwalski P, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Expert Consensus of the Association of Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society and the Polish Society of Cardio-Thoracic Surgeons, approved by the Board of the Polish Cardiac Society. Kardiol Pol. 2017;75(9):937-64. [ Links ]

48. Hajaj M, Karim A, Pascaline S, Noor L, Patel S, Dakka M. Impact of MRI on high grade Ductal Carcinoma Insitu (HG DCIS) management, are we using the full scope of MRI?Eur J Radiol. 2017;95:271-7. [ Links ]

49. Coylewright M, Mack MJ, Holmes DR Jr, O'Gara PT. A call for an evidence-based approach to the Heart Team for patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(14):1472-80. [ Links ]

50. Martínez GJ, Seco M, Jaijee SK, Adams MR, Cartwright BL, Forrest P, et al. Introduction of an interdisciplinary heart team-based transcatheter aortic valve implantation programme:short and mid-term outcomes. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):876-83. [ Links ]

51. Showkathali R, Chelliah R, Brickham B, Dworakowski R, Alcock E, Deshpande R, et al. Multi-disciplinary clinic:next step in "Heart team"approach for TAVI. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(2):453-5. [ Links ]

52. Otto CM, Nishimura RA. New ACC/AHA valve guidelines:aligning definitions of aortic stenosis severity with treatment recommendations. Heart. 2014;100(12):902-4. [ Links ]

Received: July 11, 2018; Accepted: November 20, 2018

text in

text in