Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death in the world.1 Mechanism beyond coronary artery disease is atherosclerosis2 and risk factors to develop it were described for the first time by Framingham and are: arterial systemic hypertension (ASH), diabetes mellitus (DM), hypercholesterolemia and smoking.3

Smoking, sedentarism, atherogenic diet, arterial systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome are considered modifiable risk factors. Instead; masculine gender, chronic kidney disease, postmenopausal state, advanced age and coronary disease family background are non-modifiable factors.4---6 Also, considered as emergent coronary risk factors are: high sensibility to C reactive protein (HS-CRP), hyperhomocys- teinemia, glycemic fast concentrations, leukocyte counting as well as coronary calcium score measured by computed tomography, Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI), periodontal disease, lipoprotein levels and carotid artery intima media thickness.7 However current evidence does not sustain a routinely measurement for vascular risk stratification.8 On the other side, three-vessel coronary artery disease (TVCAD) is an atherosclerosis advanced manifestation and it is defined as a stenosis ≥70% in each major epicardial coronary artery.9 Most of these patients should require a revascularization strategy (surgical or percutaneous) to ameliorate their symptoms and life hope.10 Syntax score is an angiographic tool grading coronary lesions complexity and which allows obtaining evidence based on clinical practice guides and select the best revascularization techniques.11,12 This score is also used to analyze coronary anatomy, when an elevated value, a complex coronary anatomy associated to atherosclerotic damage is revealed.11,13 Studies in Mexican population reported high frequency of coronary risk factors (CRF) as obesity, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, saturated fat intake.14,15 Nevertheless, there is no literature report about coronary risk factors in patients with three-vessel coronary artery disease. The objective of this study was to describe demographic, clinic, anthropometric, angiographic and biochemical characteristics in a group of patients with three-vessel coronary artery disease in Northwest México.

Methods

An observational and descriptive study was performed from May 2015 to February 2016 in a third level hospital at Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in ciudad Obregon, Sonora México. This is the regional referral hospital for four states in the northwest of Mexico (Sonora, Sinaloa, Baja California and Baja California Sur). Mestizo population, older than 18 years were studied, all of them with three-vessel coronary disease diagnostic16 (stenosis ≥70% in each epicardial major coronary arteries). A convenience sampling of a hundred consecutive patients was obtained from May 2015 to February 2016. An anal- ysis with the Kolmogorov---Smirnov test was performed to know the normality of the population prior to the analysis of results. Local Research Ethics Committee approved the protocol. Written informed consent for each patient was asked during hospital stay when three-vessel coronary disease was assessed by coronariographic study. Anthropometric measurements as weight, length/height for age, body mass and fat index (BMI) were obtained with light clothes, no shoes and using a Tanita TBF-215 body composition analyzer. Abdominal circumference ratio was assessed with the World Health Organization’s recommendations17 and BMI calculated with Quetelet formula.18 Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) was evaluated with a Sonotrax Edan 8 Hz catheter and to interpret it, method measurements and abnormal definitions from the American Heart Association’s scientific consensus were taken.19

After a 12 h fast, blood samples were taken to qualify lipid, glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), urea, creatinine, uric acid. All laboratory tests were performed with a AU680 Analyzer-Beckman Coultier, Inc equipment with clinical chemistry standardization methods. Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c fraction (HbA1c) was performed with a DCA Vantage Analyzer, SIEMENS (NGSP approved). Syntax score was done by an interventional cardiologist who remained blind to patient’s risk factors and got help from Syntax calculator version 2.11.13 Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) as well as other clinical parameters were obtained from the clinical records, American Society for Echocardiography recommendations for LVEF were considered.20

Left main coronary artery disease was defined with ≥50% luminal stenosis by visual estimation during coronariography; systemic arterial hypertension with blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or if users of antihypertensive treatment. Criteria for diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome were the ones recommended by American Diabetes Association (ADA) and International Diabetes Federation (IDF).21,22

Familiar background for cardiovascular disease was considered when one or more first grade family members have undergone acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident or cardiovascular death; in women, younger than 65 or in men younger than 55 years old.7 Sedentary lifestyle was set when patient had physical activity less than 30 min, 5 days a week,23 smoking with intake > 100 cigarettes in patient’s whole life, active smoking with an intake of at least a part of a cigarette in the last 30 days,24 to estimate packages/year: multiply smoking years by smoked packages of cigarettes daily. Hyperuricemia was diagnosed when uric acid was ≥7 mg/dL and chronic renal disease when glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was <60 mL/min.25

Dyslipidaemia was assessed with cholesterol values ≥200 mg/dL, high-density lipoproteins (HDL-C) ≥40 mg/dL, low-density lipoproteins (LDL-C) ≥100 mg/dL or triglycerides level ≥150 mg/dL. Stable or unstable angina, silent ischemia, acute myocardial infarction with or without ST-segment elevation (AMI with STSE or AMI without STSE) were classified according to the European Society of Cardiology and American Heart Association practice guidelines.26---28 SPSS program version 20 for Windows® was used for statistical analysis. Numerical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Kolmogorov---Smirnov test was used to analyze the distribution of the data. To show differences among numerical variables with normal distribution and independent samples, a Student t test was used. Qualitative values were assessed with a Pearson---Fisher chi square test. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant difference.

Results

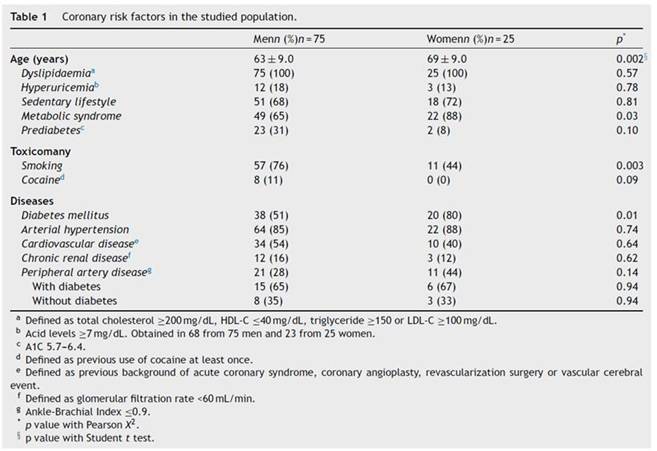

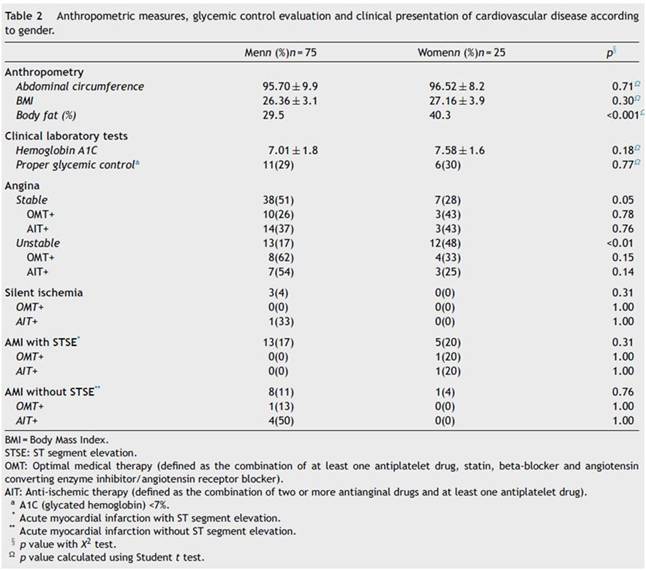

From the 25 women and 75 men studied, women had a higher average age than men when diagnosed (69 ± 9.0 years old, p = 0.002). A higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome was associated with feminine gender (88%), instead in males was 65% (p = 0.03). On the opposite, 76% of men had smoking habit while there were just 44% of smoking women (p = 0.003). In addition, previous cocaine use was present in 11% of men (p = 0.09).

Related to chronic diseases, diabetes mellitus was found in 80% of women compared to 51% of men (p = 0.01). No meaningful differences in arterial hypertension (p = 0.74), cardiovascular disease (p = 0.64) neither chronic renal disease (p = 0.62) were found (Table 1). A noticeable difference in body fat was evident, being higher in women compared to men (40.3% versus 29.5%, p < 0.001). Glycemic control was achieved in less than a 30% of both genders, with no differences between them (Table 2).

The most common clinical presentation of cardiovascular disease was stable angina (45%), and masculine group the most affected (51%). Whereas women group showed a higher frequency of unstable angina (48%), 3 cases in the masculine group got silent ischemia and a 28% acute infarction prevalence where most of the cases were AMI with STSE. Optimal medical therapy was established in 26% of males and 43% of females presenting as stable angina (p = 0.78) (Table 2).

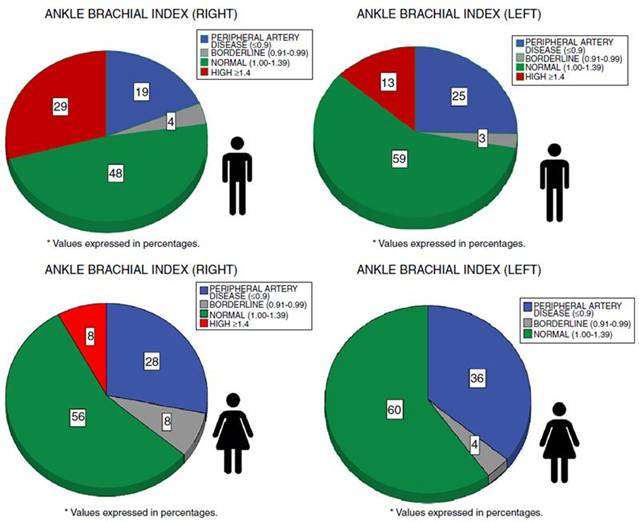

Ankle-Brachial Index was abnormal in 58% of the patients (ABI <1 or ≥1.4); 28% men and 44% women were diagnosed with peripheral arterial disease (ABI ≤0.9; p = 0.14) (Fig. 1). Within the patients having peripheral artery disease 65% of males and 67% of females were diabetic (p = 0.94). About Syntax score, no significative differences associated to gender were observed (p = 0.56). No meaningful differences in left main coronary artery disease, as well as low, intermediate or high Syntax score (Table 3).

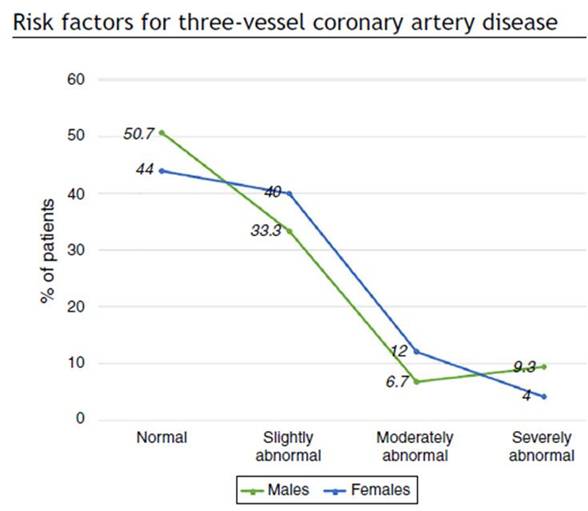

Finally, 51% of patients got a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) abnormally low. Thirty three percent of men and forty percent of women, got a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), slightly abnormal. On the other hand, 6.7%

of men and 12% of women showed a left ventricular ejection fraction, moderately abnormal (31---40%). And 9.3% of men and 4% of women resulted with a left ventricular ejection fraction, severely abnormal --- equal to or less than 30% (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Three-vessel coronary artery disease is an advanced manifestation of atherosclerosis,29 thus, most patients with this disease require a surgical or percutaneous strategy to improve their symptoms and prognostic. As it was also important to describe cardiovascular risk factors (CRF), in the present study; demographic, anthropometric, biochemical, angiographic and Ankle-Brachial Index are considered in a sample with three-vessel coronary artery disease in Northwest México.

Important to mention that diet and lifestyle changes in this people also affect .30 However, our study did not evaluate diet habits as a coronary risk factor which could be a limitation to suggest a relation with TVCAD. A high consumption of a diet rich in simple carbohydrates is very common and, fruit and vegetables are rarely eaten.31 Nevertheless, this does not fully explain the differences that some authors have suggested in relation to feeding as an independent cardiovascular risk factor, but it does take into account the presence of genetic factors identified in the Mexican population that could confer a greater risk as has been suggested.32,33

Traditional diet in this Mexican area includes saturated lipids in grilled meat, fresh cheese and tamales.30 Consequently, there is a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, saturated lipids intake and smoking.14,15 The effects of cocaine are well-known, such as increased inotropic and chronotropic, vasoconstriction, pro thrombotic state, endothelial dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis.34,35 A finding of our study was that an 8% of the patients with TVCAD had been occasionally cocaine users. However, we did not find that this could have an association with the current clinical picture due to the age of presentation that is higher in these patients than described in people affected by cocaine use.

High prevalence of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome is remarkable in the studied sample. Other researches in patients with three-vessel coronary artery disease like Syntax score, report a prevalence of just 25% for diabetes mellitus and 45% for metabolic syndrome.11 ‘‘CREDO Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort-2’’, a Japanese study, reports diabetic with three-vessel coronary artery disease in only 50% of their population.36

Besides, another possible explanation for the differences found, could be the cut-off point to define a significative coronary stenosis. In Syntax study and ‘‘CREDO Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort-2’’ approaches, a 50% cutting point was the reference for a significative stenosis, whereas

in our approach a 70% cutting point was used. This 70% was considered due to the discrepancies between the 50% cut- off point and the coronary blood flow (CBF) reserve ≤0.8 (considering the gold standard to diagnose a coronary stenosis ischemic potential). To use a 70% cut-off point improves angiographic specificity to detect ischemic potential in a coronary stenosis, even when it decreases its sensibility.37 A limitation of our study was the fact of taking only the evaluation of a single interventional cardiologist but who nevertheless had extensive experience and professional certification to do so.

Sociocultural and ethnical differences might also be involved in a higher risk profile in our sample, which could determine do not follow indicated treatment neither special diet as reduce salt consumption or improve physical activity, have a hypertensive control, etc.38 For instance, glycemic control was good enough just in 29% of the diabetic people. Considering diabetic and pre-diabetic subjects together, 81.36% of men and 88% of women had an abnormal glucose metabolism; alarming data due to the high morbidity and mortality in this group of patients.39 Dyslipidemia was the most common risk factor, despite the use of hypolipemiant drugs 100% of the sample registered any other lipid parameter away from target. Probably due to a lack of adjusting to therapeutic instructions or even more, to hereditary lipid disease with specific genomic mutations not measured in the present study.40 Therefore, sedentary lifestyle, atherogenic diet and tobacco consumption are essential factors that influence dyslipidemia in Northwest Mexican population.41

Ankle braquial index (ABI) ≤0.9 is associated with a higher mortality frequency as well as cardiovascular events.42 ABI ≥1.4 is related with acute myocardial infarction but not with an increase in mortality,43 and ABI limit value (0.91---0.99) is associated with endothelial dysfunction.44 Based on these and in accordance with the American Heart Association’s scientific consensus to measure and interpret ABI, all values out of range from 1.00 to

Figure 1 Ankle-Brachial Index values according to gender. Ankle-Brachial Index was normal if it was between 1.00 and 1.39. Ankle-Brachial Index was abnormal if it was <1 or ≥1.4. Peripheral arterial disease was diagnosed if Ankle-Brachial Index was ≤0.9. Borderline arterial disease was diagnosed if Ankle-Brachial Index was between 0.91 and 0.99.

1.39, are considered as abnormal,19 so it was found that 58% of studied sample had an abnormal ABI, higher in the right side and lower in theft side in men and abnormally low in both sides in women. Differences which might be due to a higher risk profile in women than men (women were older, with a higher diabetes load, metabolic syndrome and several types of dyslipidemia). Higher ABI mainly in the right side, has been associated with blood pressure measurement in 4 limbs (it usually starts in the right side, when patient could get an anxiety transitory rise in blood pressure, mitigated

Figure 2 Left ventricular ejection fraction according to gender. Normal: LVEF 52---72 for males and 54---74 for females. Slightly abnormal: LFEF 41---51 for males and 41---53 for females. Moderately abnormal: LVEF 30---40 for both genders. Severely abnormal: LVEF <30. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction %.

effect during blood pressure measurement in the rest of the limbs).19

Other possible explanations for this fact might be: muscular mass (most of the people is right-handed), embryologic development and anatomic preference atherosclerotic plaques formation in specific sites.45---47

Because of difficult coronary lesions in the studied sample, Syntax score was high in most patients (37 ± 11.6). Compared with FREEDOM study, where Syntax score was 26.2 ± 8.4 (a diabetic sample with 82.8% of patients with TVCAD)48; in Syntax study, the average was 28.8 ± 11.5. Differences which could probably be explained for an adverse risk profile in our studied cases, but mainly, by using a ≥70% cut-off point (instead of a >50%) to define a meaningful coronary stenosis. It has been recently demonstrated that considering ≥70% cut-off point to indicate revascularization, decreases adverse events rate in a year and the number of stents used, also providing a much better functionality in revascularization strategy.49

Finally, a high prevalence of coronary risk factors and complex coronary anatomy (High Syntax scores) might lead to a worse prognosis than the reported from other researchers.10,39 SYNTAX II is score which combines coronary anatomy and clinical variables (age, renal function, left ventricular ejection fraction, gender, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and peripheral artery disease), this recently developed score substantially increased the accuracy of identifying low (and high) risk patients compared to the anatomical SYNTAX score alone.50,51

Conclusions

Our study found a significant prevalence of diabetes mellitus, smoking and metabolic syndrome associated for three-vessel coronary artery disease at our studied sample. These might lead to complex coronary lesions and probably a worse prognostic. Most patients showed an abnormal Ankle-Brachial Index sighting toward a generalized atherosclerosis.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)