Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos de cardiología de México

versión On-line ISSN 1665-1731versión impresa ISSN 1405-9940

Arch. Cardiol. Méx. vol.78 no.3 Ciudad de México jul./sep. 2008

Revisión sistematizada

Fibrinolytic therapy in left side–prosthetic valve acute thrombosis. In depth systematic review

Terapia fibrinolítica en el corazón izquierdo

Esteban Reyes–Cerezo,* Carlos Jerjes–Sánchez,* Támara Archondo–Arce,* Anabel García–Sosa,* Ángel Garza–Ruiz,* Alicia Ramírez–Rivera,* Carlos Ibarra–Pérez**

* Emergency Care Department. Hospital de Cardiología UMAE 34, Centro Médico del Norte, IMSS, Monterrey City, Nuevo León,México.

** Head Editor of Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias, México DF.

Correspondence:

Dr. Carlos Jerjes–Sánchez.

Santander Núm. 316,

Col. Bosques de San Ángel Sector Palmillas,

66290, San Pedro Garza García, NL, México.

Phone and fax: (5281) 83100753.

E–mail: jerjes@prodigy.net.mx; jerjes@infosel.net.mx

Recibido: 28 de febrero de 2007

Aceptado: 12 de febrero de 2008

Abstract

Background: Limited data are available on the impact and safety of fibrinolytic therapy (FT) in left – side prosthetic valve acute thrombosis (PVAT). Study objective: To improve our knowledge about the FT role in left –side PVAT.

Design: Bibliographic search and analysis.

Methods: MEDLINE search from January 1970 to January 2007. Studies were classified according to the evidence level recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians and included if they had objective diagnosis of leftside PAVT and FT efficacy assessment (hemodynamic, echocardiographic or fluoroscopic improvement). New York Heart Association class was used to establish functional state. Data on clinical characteristics, diagnosis strategy, anticoagulation status, fibrinolytic and heparin regimens, cardiovascular adverse events, outcome, and follow–up were also required.

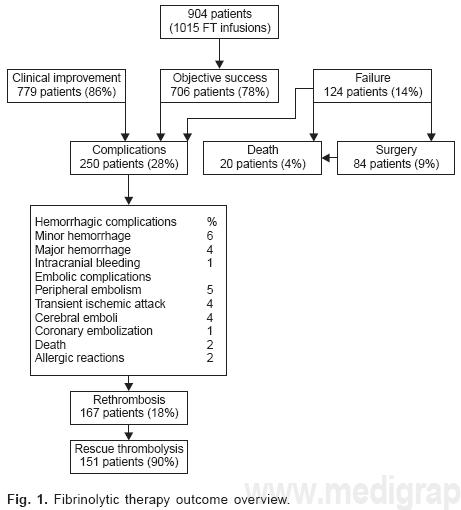

Results: A systematic search produced a total of 900 references. Each abstract was analyzed according to the predetermined criteria. Thirty–two references with 904 patients constitute the subject of this analysis. Only one trial had evidence III and thirty–one evidence V. FT was more used in young female patients (64%) with prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis (77%), and clinical instability (82%). Transesophageal echocardiogram had a higher thrombus detection rate (100%). Although several fibrinolytic regimens were used in a first or second course, streptokinase was the most frequent agent (61%). Clinical improvement was observed in 86% of the patients, objective success in 78%, and failure in 14%. Rescue fibrinolysis was done in 17%. Complications: peripheral and cerebral embolism rate was 5% and 4%, respectively. Major bleeding 4% and intracranial hemorrhage 1%.

Conclusions: The available evidence demonstrates that in PVAT fibrinolytic therapy improves the outcome in younger, more ill patients, especially females, independently of the fibrinolytic regimen used with a low complications rate.

Key words: Thrombolysis. Fibrinolytic therapy. Cardiac valve thrombosis. Valve prosthesis.

Resumen

Antecedentes: Son limitados los datos disponibles sobre el impacto y seguridad de la terapia fibrinolítica (TF) en trombosis vascular aguda de válvulas protésicas izquierdas (TVA). Objetivo del estudio: Mejorar nuestro conocimiento en relación al papel de la TF en TVA de válvulas izquierdas.

Diseño: Análisis e investigación bibliográfica.

Métodos: Investigación a través del MEDLINE de enero de 1970 a enero de 2007. Los estudios se clasificaron de acuerdo a las recomendaciones del nivel de evidencia del "American College of Chest Physicians" y se incluyeron si tenían un diagnóstico objetivo de TVA de prótesis válvula izquierda y valoración de la efectividad de laTF (mejoría hemodinámica, ecocardiográfica o fluoroscópica). Se utilizó la clase funcional de la "New York Heart Association" para evaluar la clase funcional. También se requirieron datos de las características clínicas, abordaje de diagnóstico, estado de anticoagulación, regímenes de heparina y del fibrinolítico, eventos adversos cardiovasculares, evolución y seguimiento.

Resultados: a través de una investigación sistematizada se obtuvo un total de 900 referencias. Cada resumen se analizó de acuerdo a los criterios predeterminados. Treinta y dos referencias que incluyeron 904 pacientes constituyen la base de este análisis. Sólo un estudio tuvo un nivel de evidencia III y en 31 el nivel de evidencia fue V. La TF se utilizó principalmente en pacientes jóvenes del sexo femenino (64%) con trombosis en prótesis mecánicas en posición mitral (77%) y con inestabilidad clínica (82%). El ecocardiograma transesofágico tuvo el mayor porcentaje de detección de trombo (100%). Aunque varios regímenes fibrinolíticos fueron utilizados en una primera o segunda infusión, la estreptoquinasa fue el fibrinolítico más utilizado (61%). Se observó mejoría clínica en el 86% de los pacientes, éxito objetivo en el 78% y falla en el 14%. UnaTF de rescate se realizó en el 17%. Complicaciones: embolia periférica o cerebral se observó en el 5 y 4%, respectivamente. Hemorragia mayor en el 4% e intracraneal en el 1%.

Conclusiones: La evidencia disponible demuestra que la TF en TVA mejora la evolución en pacientes jóvenes graves, especialmente del sexo femenino, independientemente del régimen fibrinolítico utilizado con una baja incidencia de complicaciones.

Palabras clave: Trombólisis, Terapia fibrinolítica. Trombosis de válvula cardíaca. Prótesis valvular.

Although left–side prosthetic valve acute thrombosis (PVAT) is not a health problem, it is a serious and potentially lethal complication of heart valve replacement surgery. The conventional surgical treatment has a high mortality rate in urgent and emergency cases and is available only in few very specialized centers.1 The advent of fibrinolytic therapy (FT) has improved the outcome among properly selected acute myocardial infarction2 high–risk pulmonary embolism,3,4 acute ischemic stroke,5 and complicated hemothorax or empyema patients.6 In the setting of left–side PVAT,1,7,8 FT has been considered an alternative for high–risk surgical patients. However, even after the earliest FT successful report9 and guidelines recommendations,10,11 this therapeutic approach is sometimes considered harmful and several questions still remain unsolved.12 In the era of evidence–based medicine and of the new antithrombotic and fibrinolytic drugs, we performed a 37–year systematic literature review attempting to improve our knowledge about FT role in PVAT.

Methods

Study identification: a MEDLINE search on FT and PVAT was undertaken (National Library of Medicine: PubMed: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The literature was scanned by formal searches of electronic databases with the terms: "cardiac valve thrombosis", or "prosthetic valve obstruction", or "prosthetic heart valve" and "thrombolysis" were entered in the search field. Only English–published abstracts were considered.

Study eligibility: two investigators abstracted the data (ERC, TAA) and disagreements were resolved by discussion with another investigator (CJS). No attempts were made to contact the authors for information. Investigators were not blinded to journal, author o institution. Case reports (arbitrary limit < 3 cases) and patients younger than 13 year old were not included. Trial selection: full text studies were included if they met all of the following criteria, decided a priori: a) clinical characteristics, b) NYHA functional class, c) diagnostic work–up, d) objective approach for the diagnosis of PVAT, e) FT efficacy assessment, f) fibrinolytic regimens, g) cardiovascular adverse events (hemorrhagic complications, embolization, cardiac failure, rethrombosis or cardiovascular death), h) and description of at least one of the following data: age, anticoagulation status, heparin regimens, outcome and follow–up. Acute pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock were considered as NYHA IV class. Evidence level: studies were classified according to the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations:13 level I, based on randomized trials with high power; level II, randomized trials with lower power; level III, non–randomized cohort studies with treated and untreated groups; level IV, non–randomized historical cohort studies with treated and untreated groups; level V, case series without control subjects. Fibrinolytic therapy assessment definition: a) objective success (hemodynamic measurements, echocardiographic or fluoroscopic parameters with gradient flow improvement, thrombus size reduction and/or opening angle improvement), b) clinical success (baseline clinical characteristics improvement) and c) non–success (failure to improve clinical, echocardiographic, or fluoroscopic baseline findings or death). We did not have any support for this study from pharmaceutical companies or government agencies.

Results

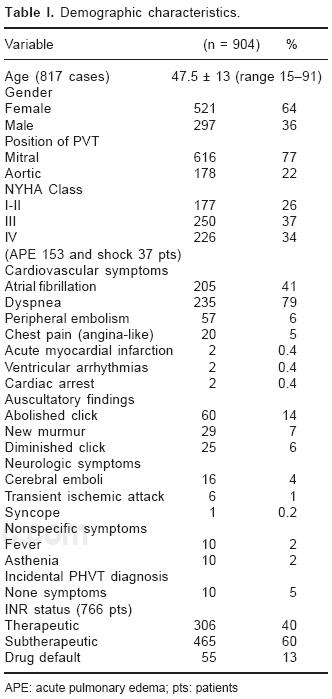

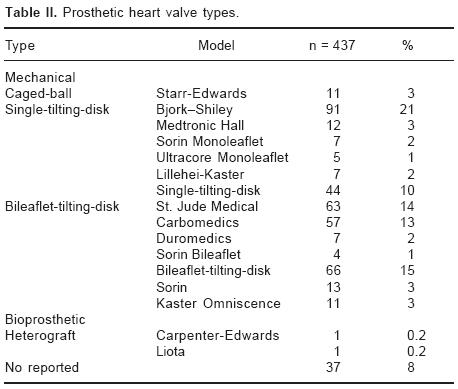

From January 1970 to January 2007 a systematic MEDLINE/PubMed search produced a total of 900 references with abstracts. Thirty–two12,14–34,43–52 studies with 904 cases met all of the inclusion criteria and constitute the subject of this analysis. Only one trial 25 had evidence III and the other 31 were case series (evidence V). A composite list of the baseline characteristics of 904 patients is shown in Table I. The majority were young females with prosthetic mitral valve thrombus location, cardiovascular symptoms, and severe clinical instability. A low rate of auscultatory and neurologic findings was found. PVAT was observed in patients with or without therapeutic INR values. The list of the different types of prosthetic heart valves is shown in Table II.

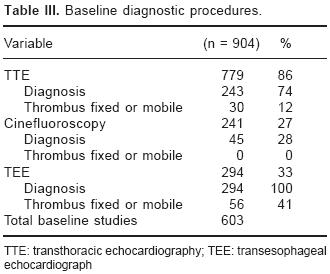

Diagnostic procedures: the most common diagnostic approach was transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in 86%. Cinefluoroscopy and transe–sophageal echocardiograms (TEE) were done in 27% and 33% respectively. The baseline echo and cinefluoroscopy characteristics, as well as the diagnostic yield of the procedures, are summarized in Table III. TEE had a better thrombus detection rate as compared to TTE and cinefluoroscopy (Table III).

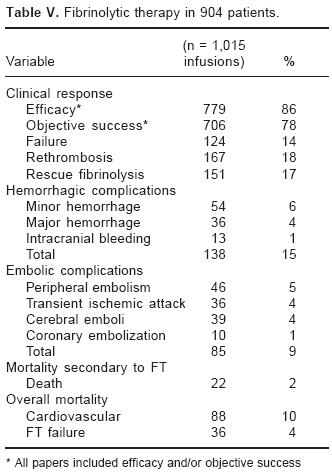

Fibrinolytic therapy: in 904 patients, 1,015 fibrinolytic regimens were used as a first course or rescue fibrinolysis. Indications: most studies included critically ill patients who were too sick to undergo immediate surgery (severely hemodynamically compromised) (Table I). Fibrinolytic regimens: table IV summarizes the main fibrinolytic regimens and repeated FT administrations used throughout the study period. Streptokinase was the most used fibrinolytic agent (63%)12–24,26,30,33,34,45,47,49,50–52 compared to urokinase (15%) 14–16,21–23,26,29,45,49–51 and alteplase (18%) 21,23,25,27,28,31,34,44,46,48–50 fiolus administration followed by long–term infusions was used in the majority of the cases. The infusions of strep tokinase were longer (24 to 72 hours), followed by urokinase (12 to 15 hours) and alteplase (5 hours). Short–infusions were used mainly with alteplase (90 minutes to 3 hours) and in a few cases of streptokinase (90 minutes to 1 hour) (Table IV).

The clinical response, hemorrhagic and embolic complications and mortality secondary to FT are shown in Table V. In the group with FT failure, 7% required surgery.14–16,21,23,27,30,31,33,34,44–50,52 In patients with FT failure, rescue fibrinolysis (a second course) was done in 17%. Only 1% (11 cases) of intracranial bleeding was reported.12,14–16,19–22,26,31,34,47,49,50 The incidence of major and intracranial hemorrhage was low and the overall hemorrhagic and embolic complications rate was 7%, embolic 70% and hemorrhagic 30%. A close relationship among hemorrhagic complications, vascular punctures, and central catheter line was found. The mortality cause secondary to FT was cerebral emboli in 13 patients, intracranial bleeding in 5, serious bleeding in 3 and peripheral hemorrhage in one patient. Most patients were under long–term (12 to 96 hours) infusions.12,18,21,33,47,49,52 In spite of the broad use of streptokinase, a low rate of allergic reactions (1%) was reported.19,23,26,30,50,52 The main overall mortality was cardiovascular. Fibrinolytic therapy failure was attributed mainly to rethrombosis. When a follow–up was performed, 13% of mortality was described.12,14–16,18,19,21–23,26,27,30,34,43,47,48–52A FT outc ome overview is shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

Available data provided a thirty–seven–year broad view and clinically relevant information about FT efficacy and safety in the setting of left–side PVAT. This result supports previous knowledge coming from American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines 10,11 and identifies current evidence that could be used in the clinical practice.

Although, the clinical characteristics of PVAT have been clearly defined, 15 the clinical profile in this study included young patients, with mitral thrombus and cardiovascular instability without comorbidity, independently of the anticoagulation status (Table I). There is not a clear explanation for the small incidence of aortic PVAT seen in the reviewed cases. In addition, there were no differences in PVAT rate amongst old or new generation mechanical valves or in those with high or low thrombogenic profile (Table II). There is not a satisfactory explanation regarding the low incidence (3%) of PVAT in patients with Starr–Edwards in aortic or mitral position, in spite of its high thrombus risk profile. All prosthetic valve types developed thrombus, independently if patients were or not under effective oral anticoagulation. Transthoracic echocardiogram and TEE were the main tools in the diagnostic process;32 both techniques are quite specific, reproducible, and useful to diagnose left–side PVAT, and to monitor thrombus lysis. Moreover, TEE offers better resolution allowing more direct thrombus visualization (Table III).

FT represents an alternative management to surgery, with a convincing biological benefit by inducing lysis of the obstructive thrombus; the rapid improvement through "pharmacologic embolectomy" possibly reverses the clinical instability and prevents death. The high FT success rates observed, particularly in critically ill patients, support this pharmacologic action and establish this therapeutic approach as an important alternative when operative mortality could be higher than the risk of hemorrhagic or embolic complications.12,14–34,43–52 Due to the lack of a standard regimen 10,11 several infusion protocols and doses have been tried, in this setting long–term streptokinase infusion was the most frequently used regimen (Table IV); the benefit obtained with this non–fibrin specific fibrinolytic agent in the setting of severe clinical instability could be explained through its long intra–vascular half–life, resulting in a higher systemic fibrinolytic state than that produced by fibrin–specific agents. Although the experience with alteplase is scarce, considering its main advantages, are short half life, more fibrin specificity, less blood requirements after surgery, the capability to dissolve fresh cerebral embolus and a faster achievement of valve opening, it emerges as an important therapeutic approach in unstable patients.34 Any comparison among fibrinolytic agents is unjustified due to the small number of courses and the nonrandomized fashion in which these agents were given.

In the setting of partial or total failure or early reocclusion after FT (16%), a second course of fibrinolysis was a successful approach with a low complication rate;12,14–16–19–22,26,31,34,47–52 al though evidence in this field is very limited, a trend to improve initial results with repeated FT sessions has been reported. 12,34,47–52 No specific agent or regimen to obtain optimal results was identified. In addition, no information regarding new antithrombotic or fibrinolytic drugs (tecneteplase, low molecular weight heparins, platelet glycoprotein Ilb/IIIa integrin receptor blockade or clopidogrel) was available in the reviewed literature.

Even in properly selected patients, independently from the vascular thrombosis location, intracranial bleeding is the most serious and feared FT complication. The low intracranial bleeding rate (1%) was similar to that observed in acute myocardial infarction35–37 and it could be explained by the age of the patients and the broader streptokinase use, instead of fibrin–specific agents. On the other hand, long–term fibrinolytic infusions were excellent models for severe hemorrhage complications, similarly to those observed in pulmonary embolism.38 Additionally, all patients whose mortality was attributed to FT complications were under long–term infusions. Although short–term streptokinase and alteplase infusion experience is scarce and more information is required, these regimens, by peripheral vein followed by a second course when needed, could be an attractive therapeutic option. Regarding hemorrhagic complications, the rate of major and minor bleeding events was higher than previously reported12 (Table V), however, a close relationship with venous invasive procedures was found. Avoiding catheter central line placement could reduce bleeding complications as has been observed in pulmonary embolism.3,4,38 In this research, overall systemic embolism was far above predictable, however, the cerebral emboli rate was low. Recurrence and cardiovascular mortality in acute phase and follow–up were high, which is explained by the extremely serious condition of patients and the absence of intensive antithrombotic treatment to reduce recurrence. In addition, in this group of patients, the attempts to identify persistent active thrombosis through inflammation and haemostatic risk markers, as in acute coronary syndromes,39 have been scarce.33 Compared with a previous experience in which long–term FT regimens were used53 our data suggesting higher FT success rates in terms of mortality. Bleeding complications were not reported.53

Limitations of the study

Randomized trials and homogeneity among publications were not identified. 40 We did not contact the principal investigators for verification of the published data. Certainly, the trend in medicine is to publish successful cases, so it is possible that we do not know the real number of failure cases.

Evidence–based considerations

1. All prosthetic heart valves types can develop thrombus in the presence of ineffective or apparently effective oral anticoagulation.

2. More data are required in aortic PVAT, class I or II, and cardiogenic shock cases, as well as in patients with underlying comorbidity.

3. In the PVAT diagnostic process, TTE and TEE should be considered as the main diagnostic tools.

4. Although all FT regimens were effective, long–term infusions may be harmful since they are associated to hemorrhagic complications.

5. New adjunctive or concomitant intensive antithrombotic treatments are required to avoid high recurrence rates.

6. The benefit observed in young patients overcomes the intracranial bleeding risk of FT.

7. In the setting of FT failure or early recurrence, rescue FT course was an effective and safe therapeutic approach.

8. Short–term infusions following a second FT course among properly selected patients could be an attractive regimen waiting for scientific support.

9. Direct comparison between FT and surgical therapy seems unlikely in the future, because these patients are so sick and the disease so infrequent, that probably a randomized controlled trial will never be undertaken.

10. Although there are no randomized trials and there is a conspicuous lack of homogeneity among publications, the present data confirm previous observations10,53 regarding the efficacy and safety of FT in left–side PVAT and updates its clinical significance41,53 and beneficial effects.42,53

Conclusions

The available evidence demonstrates that, in PVAT, fibrinolytic therapy improves the outcome in younger, more ill patients, especially in females, independently of the fibrinolytic regimen used with a low complications rate.

References

1. Huseybe DG, Pluth JR, Piheler JM: Reoperation on prosthetic heart valves an analysis of risk factors in 552 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983; 86: 543–552. [ Links ]

2. Braunwald E, Cannon C, McCabe CH: Use of composite endpoints in thrombolysis trials of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1993; 72: 3G–12G. [ Links ]

3. Jerjes–Sanchez C, Ramirez–Rivera A, Garcia MM, Arriaga–Nava R, Valencia S, Rosado–Buzzo A, et al: Streptokinase and heparin versus heparin alone in massive pulmonary embolism: A randomized controlled trial. J Thromb Thrombolysis 1995; 2: 227–229. [ Links ]

4. Jerjes–Sanchez C, Ramirez–Rivera A, Arriaga–Nava R, Iglesias–González S, Gutierrez P, Ibarra–Perez C, et al: High dose and short–term streptokinase infusion in patients with pulmonary embolism. Prospective with seven–year follow–up trial. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2001; 12: 237–247. [ Links ]

5. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt–PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1581–1587. [ Links ]

6. Jerjes–Sanchez C, Ramirez–Rivera A, Elizalde GJ, Delgado R, Cicero R, Ibarra–Perez C, et al: Intra–pleural fibrinolysis with streptokinase as an adjunctive treatment in hemothorax and empyema. A Multicenter Trial. Chest 1996; 109: 1514–1519. [ Links ]

7. Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR: Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation 1994; 89:635–641. [ Links ]

8. Akins CW: Results with mechanical cardiac valvular prostheses. Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 60:1836–1844. [ Links ]

9. Bailie Y, Choffel J, Sicard MP: Traitement throm–bolytique des thromboses de prothese valvulaire (Letter). Nouv Presse Med 1974; 3: 1233. [ Links ]

10. Lengyel M, Fuster V, Keltai M, Roudaut R, Schulte HD, Seward JB: Guidelines for management of left–side prosthetic valve thrombosis: a role for fhrombolytic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30: 1521–1526. [ Links ]

11. Bonow RO, Carabello B, de Leon AC: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines, (committee on management of patients with valvular heart disease). J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32: 1486–1582. [ Links ]

12. Özkan M, Kaymaz C, Kirma C, Sonmez K, Ozdemir N, Balkanay M, et al: Intravenous thrombolytic treatment of mechanical prosthetic valve thrombosis: a study using serial transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 1881–1889. [ Links ]

13. Fourth American College of Chest Physicians consensus conference on antithrombotic therapy. Chest 1992; 102 (Suppl): 1S–549S. [ Links ]

14. Witchitz S, Veyrat C, Moisson P, Scheinman N, Rozenstajn L: Fibrinolytic treatment of thrombus on prosthetic heart valves. Br Heart J 1980; 44:545–554. [ Links ]

15. Ledain LD, Ohayon JP, Colle JP, Lorient–Roudaut FM, Roudaut RP, Besse PM: Acute fhrombotic obstruction with disc valve prostheses: Diagnostic considerations and fibrinolytic treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986; 7: 743–751. [ Links ]

16. Lorient – Roudaut MF, Ledain L, Roudaut R, Besse P, Boisseau MR: Thrombolytic treatment of acute thrombolytic obstruction with disk valve prostheses: Experience with 26 Cases. Semin Thromb Hemost 1987; 13: 201–205. [ Links ]

17. Zoghbi WA, Desir RM, Rosen L, Lawrie GM, Pratt CM, Quiñones MA: Doppler echocardiography: Application to the assessment of successful thrombolysis of prosthetic valve thrombosis. J Am Soc Echo 1989; 2: 98–101. [ Links ]

18. Wilkinson GAL, Williams WG: Fibrinolytic treatment of acute prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. Five cases and a review. Eur J Cardio–Thorac Surg 1989; 3: 178–183. [ Links ]

19. Dzavik V, Cohen G, Chan KL: Role of transesophageal echocardiography in the diagnosis and management of prosthetic valve thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18: 1829–1833. [ Links ]

20. Vasan RS, Kaul U, Sanghvi S, Kamlakar T, Prakash N, Shrivastava S, et al: Thrombolytic therapy for prosthetic valve thrombosis: A study based on serial Doppler echocardiographic evaluation. Am Heart J 1992; 123: 1575–1580. [ Links ]

21. Roudaut R, Labble T, Lorient–Roudaut MF, Gosse P, Baudet E, Fontan F, et al: Mechanical cardiac valve thrombosis. Is fibrinolysis justified? Circulation 1992; 86 (Suppl II): II–8–II–15 [ Links ]

22. Silber H, Khan SS, Matloff JM, Chaux A, DeRobertis M, Gray R: The St. Jude valve: Thrombolysis as the first line of therapy for cardiac valve thrombosis. Circulation 1993; 87: 30–37. [ Links ]

23. Guerrero LF, Vazquez MG, Reina TA, Rodriguez BI, Fernandez ME, Aranegui LP: Thrombolytic treatment for massive thrombosis of prosthetic cardiac valves. Intensive Care Med 1993; 19: 145–150. [ Links ]

24. Solorio S, Sanchez H, Madrid R, Badui E, Valdespino A, Murillo H, et al: Trombólisis en trombosis protésica valvular mecánica. Manejo con estreptoquinasa. Arch lnst Cardiol Mex 1994; 64: 51–55. [ Links ]

25. Vi tale N, Rezulli A, Cerasoulo F, Caruso A, Festa M, De Luca L, et al: Prosthetic valve obstruction: Thrombolysis versus operation. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 57: 365–370. [ Links ]

26. Reddy NK, Padmanabhan TNC, Singh S, Kumar DN, Raju PR, Venkata – Satyanarayana P, et al: Thrombolysis in left–sided prosthetic valve occlusion: Immediate and follow–up results. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 58: 462–471. [ Links ]

27. Losi MA, Betocchi S, Briguori C, Manganelli F, Elia PP, Spampinato N, et al: Recombinant tissue–type plasminogen activator therapy in prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis: Assessment by transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Int J Cardiol 1995; 48: 219–224. [ Links ]

28. Astengo D, Badano L, Bertoli D: Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for prosthetic mitral–valve thrombosis. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 259–301. [ Links ]

29. Hernandez VE, Stainback RF, Angelini P, Krajcer Z: Thrombolytic and left–sided prosthetic valve thrombosis. Tex Heart Inst J 1998; 25: 130–135. [ Links ]

30. Manteiga R, Souto JC, Altes A, Mateo J, Aris A, Domínguez J, et al: Short–course thrombolysis as the first line of therapy for cardiac valve thrombosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998; 115: 780–784. [ Links ]

31. Munclinger MJ, Patel JJ, Mifha AS: Thrombolysis of thrombosed St. Jude medical prosthetic valves: Rethrombosis –a sign of tissue in growth–. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998; 115: 248–249. [ Links ]

32. Koca V, Bozat T, Sarikamis C, Akkaya V, Yavuz S, Ozdemir A: The use of transesophageal echocardiography guidance of thrombolytic therapy in prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Heart Valve Dis 2000; 9: 374–378. [ Links ]

33. Gupta D, Kothari SS, Bahl VK, Goswami KC, Talwar KK, Manchanda SC, et al: Thrombolytic therapy for prosthetic valve thrombosis: short and long–term results. Am Heart J 2000; 140: 906–916. [ Links ]

34. Shapira Y, Herz I, Vaturi M, Porter A, Adler Y, Birnbaum Y, et al: Thrombolysis is an effective and safe therapy in struck bileaflet mitral valve in the absence of high–risk thrombi. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 1874–1880. [ Links ]

35. ISIS–2 Collaborative Group. Randomized trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS–2. Lancet 1988; 2: 349–360. [ Links ]

36. ISIS–3 (Third International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative. ISIS–3: arandomizedcomparison of streptokinase vs tissue plasminogen activator vs anistreplase and of aspirin and heparin vs heparin alone among 41,299 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1992; 339: 753–770. [ Links ]

37. The GUSTO investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 673–682. [ Links ]

38. Goldhaber SA: Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism. Prog Cardiovas Dis 1991; 2: 113–114. [ Links ]

39. Jerjes–Sanchez C, Comparan Al, Ibarra M, Decanini H, Archondo T: Marcadores hemostáticos y de inflamación en síndromes coronarios agudos y su asociación con eventos cardiovasculares adversos. Arch Cardiol Mex 2006; 76: 366–375. [ Links ]

40. Girard P, Stern JB, Parent F: Medical literature and vena cava filters. Chest 2002; 122: 963–967. [ Links ]

41. Khot UM, Nissen SE: Is a CURE a cure for acute coronary syndromes? Statistical versus clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40: 218–219. [ Links ]

42. Vandenbrouke JP: In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 330–334. [ Links ]

43. Sanchez A, Cortadellas J, Figueras J, Gonzalez T, Soler J: Tratamiento fibirnolítico en pacientes con trombosis protésica y elevado riesgo quirúrgico. Rev Esp Cardiol 2001; 54: 1452–1455. [ Links ]

44. Azpitarte J, Sanchez J, Urda T, Vivancos R, Oyo–narte J, Malpartida F: Trombosis valvular protésica: ¿cuál es la terapia inicial más apropiada? Rev Esp Cardiol 2001; 54: 1367–1376. [ Links ]

45. Kumar S, Grag N, Tewari S, Kapoor A, Goel P, Sinha N: Role of thrombolytic therapy for stuck prosthetic valves: A serial echocardiographic study. Indian Heart J 2001; 53: 551–7. [ Links ]

46. Montorsi P, Cavoretto D, Alimento M, Muratori M, Pepi M: Prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis: can fluoroscopy predict the efficacy of thrombolytic treatment? Circulation 2003; 108: 79–84 [ Links ]

47. Ramos A, Ramos R, Togna D, Arnoni A, Staico R, Galo M, et al: Fibrinolytic therapy for thrombosis in cardiac valvular prosthesis short and long term results. Arq Bras Cardiol 2003; 81: 393–398. [ Links ]

48. Shapira Y, Vaturi M, Hasdai D, Battler A, Saguie A: The safety and efficacy of repeated courses of tissue–type plasminogen activator in patients with stuck mitral valves who did not fully respond to the initial thrombolytic course. J Thromb and Haemost 2003; 1:725–728. [ Links ]

49. Roudaut R, Lafitte S, Roudaut M, Courtault C, Perron J, Jais C, et al: Fibrinolysis of mechanical prosthetic valve thrombosis a single–center study of 127 Cases. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41: 653–658. [ Links ]

50. Tong T, Roudaut R, Ózkan M, Sagie A, Shahid M, Pontes S, et al: Transesophageal echocardiography improves risk assessment of thrombolysis of prosthetic valve thrombosis: results of the international PRO–TEE Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43: 77–84. [ Links ]

51. Balasundaram R, Karthikeyan G, Kothari S, Talwar K, Venugopal P: Fibrinolytic treatment for recurrent left sided prosthetic valve thrombosis. Heart 2005; 91: 921–922. [ Links ]

52. Caceres F, Perez H, Morlans K, Facundo H, Santos J, Valiente J, et al: Thrombolysis as first choice therapy in prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. A study of 68 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2006; 21: 185–190. [ Links ]

53. Koller PT, Arom KV: Thrombolytic therapy of left side prosthetic valve thrombosis. Chest 1995; 108: 1683–1689. [ Links ]