Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos de cardiología de México

versión On-line ISSN 1665-1731versión impresa ISSN 1405-9940

Arch. Cardiol. Méx. vol.77 no.3 Ciudad de México jul./sep. 2007

Investigación clínica

Predictors of mortality and adverse outcome in elderly high-risk patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention

Predictores de mortalidad y mal pronóstico en pacientes ancianos y de alto riesgo que van a ser sometidos a intervención coronaria percutánea

Emma Miranda Malpica,* Marco Antonio Peña Duque,* José Castellanos,* Emilio Exaire,** Oscar Arrieta,* Eduardo Salazar Dávila,* Ramón Villavicencio Fernández,* Hilda Delgadillo-Rodríguez,* Carlos J González-Quesada,* Marco A Martínez-Ríos*

* The National Institute of Cardiology, Mexico City.

** National Institute of Cancer, Mexico City.

Corresponding author:

Marco Antonio Peña Duque.

Department of Interventional Cardiology.

Instituto Nacional de Cardiología,

Juan Badiano Núm. 1, Col. Sección XVI, Delegación Tlalpan,

14080 México, D.F.

Tel.: 5573-2911 Ext. 1250

E-mail address: penmar@cardiologia.org.mx

Recibido: 27 de octubre de 2006

Aceptado: 30 de abril de 2007

Summary

Objectives: We sought to identify predictors of in-hospital and long-term (> 1 year) mortality and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in elderly patients referred for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods: Seventy-three patients (> 80 years) were included. Clinical and interventional characteristics were collected retrospectively. Primary end points were in-hospital and long-term mortality, and a composite of non-fatal myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, urgent coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and death (MACE).

Results: Eighty-three percent of the patients had acute coronary syndromes, 43% three-vessel disease, and 42% heart failure. In-hospital mortality and MACE were 16.4% and 19%, respectively. Long-term mortality and MACE were 11.3% and 16.4%, respectively. Univariate characteristics associated with in-hospital mortality and MACE were: Killip Class III-IV, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, TIMI 0-2 flow prior and after intervention, diabetes mellitus, contrast nephropathy, and presence of A-V block or atrial fibrillation (AF). Long term predictors for mortality were the presence of heart failure, cardiogenic shock, diabetes mellitus, TIMI flow 0-2 before and after intervention, and A-V block or AF.

Conclusion: The identification of the factors previously mentioned may help to predict complications in elderly patients.

Key words: Percutaneous coronary intervention. Elderly. Mortality.

Resumen

Propósito: Identificar predictores de mortalidad y de eventos cardiovasculares adversos mayores (ECAM) intrahospitalarios y a largo plazo (>1 año) en ancianos sometidos a intervencionismo coronario.

Métodos: Se incluyeron 73 pacientes (> 80 años). Se obtuvieron retrospectivamente características clínicas y del intervencionismo. Los desenlaces primarios fueron mortalidad intrahospitalaria y a largo plazo, así como un desenlace compuesto de infarto del miocardio no fatal, revascularización de vaso tratado, cirugía de revascularización coronaria y muerte (ECAM).

Resultados: 83% de los pacientes tuvieron síndrome coronario agudo o Infarto agudo del miocardio, 43% eran trivasculares, 42% presentaban insuficiencia cardíaca. La mortalidad y ECAM intrahospitalarios fueron de 16.4% y 19%, respectivamente. Mortalidad y ECAM a largo plazo fueron de 11.3% y 16.4% respectivamente. Las características que se asociaron a mortalidad y ECAM intrahospitalarios fueron clasificación de Killip III-IV, insuficiencia cardíaca, choque cardiogénico, flujo TIMI 0-2 pre y post procedimiento, diabetes mellitus, nefropatía por contraste, presencia de bloqueo A-V o fibrilación auricular (FA). Los predictores de mortalidad a largo plazo fueron insuficiencia cardíaca, diabetes mellitus, flujo TIMI 0-2 antes y después de la intervención y bloqueo A-V o FA.

Conclusiones: La identificación de estos factores de riesgo puede ayudar a predecir complicaciones en pacientes de edad avanzada.

Palabras clave: Intervención coronaria percutánea. Mortalidad. Pacientes de edad avanzada.

1. Introduction

The elderly represent the fastest growing segment of the population worldwide. The high prevalence of coronary disease in this age group has resulted in an increase of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in this population.1 The best strategy of revascularization in this group of patients has not yet been determined. Furthermore, there is contradictory information about the best treatment of both acute coronary syndrome2,3 and stable angina;4,5 however, there is agreement that advanced age is a predictor of worst outcome and increased mortality. The mechanism by which age contributes so dramatically to mortality is unknown. It has been postulated that death is precipitated in the elderly by the presence of more co-morbidities, more severe coronary disease, reduced of both cardiac and physiologic reserve.6-8

Many of the randomized clinical trials evaluating the effects of therapeutic interventions have excluded octogenarians, thereby providing limited insights to the natural history and mortality patterns of these high-risk patients.9,10 We therefore evaluated the outcome of patients > 80 years old who underwent PCI in our institution to identify the predictors of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and mortality.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Patients

From January 1997 to November 2004, 73 patients aged > 80 years underwent PCI (100 lesions) at our institution constituting the study population. The information was obtained retrospectively from patient's files.

2.2 Procedural characteristics

After informed consent, cardiac catheterization and PCI were performed by femoral approach, using a 6 or 7 Fr guiding catheter. Heparin (100 IU/kg) was administered intravenously at the beginning of the procedure and additional doses were given when necessary to maintain an activated clotting time of > 300 seconds. All patients received aspirin 300 mg/day before and 100 mg daily after the procedure. In patients receiving coronary stent, clopidogrel (300 mg as a loading dose, 75 mg/day thereafter) was administered for 6 months. Glycoprotein Ilb/IIIa inhibitors were administered at operators discretion.

2.3 Definition of variables

Death was defined as all cause of mortality. Cardiovascular death was defined as death caused by a cardiovascular cause and non-cardiovascular death as that due to a clearly documented non-cardiovascular cause. In-hospital mortality was defined as the occurrence of death during the days of hospitalization after intervention and mortality during follow-up was defined as death after discharge.

Reinfarction was diagnosed when a CPK-MB elevation to above 3 times normal or at least 50% over the previous value if CPK-MB was already elevated occurred or with the development of new abnormal Q waves in > 2 contiguous precordial leads or > 2 adjacent limb leads were present. Procedural success was considered when a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 3 and a residual diameter stenosis of < 20% were obtained. Repeat revascularization was defined as the requirement for either emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery or urgent repeat PCI after the intervention.11 Cardiogenic shock was defined as systolic pressure < 90 mm Hg for at least 30 min, or > 90 mm Hg if treated with inotropes or intraaortic balloon pump insertion, or pump failure as manifested by cardiac index < 2.2 liter/min per m2 and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure >18 mm Hg.12 Stroke was defined as the new onset of focal or global neurological deficit caused by ischemia or hemorrhage within or around the brain and lasting for more than 24 hours confirmed by image. Contrast nephropathy was defined as an absolute increase of 0.5 mg in the serum creatinine level or a 25% increase over the baseline value during the 24-48 hours after the procedure. Major bleeding loss was defined as clinically significant overt signs of bleeding associated with a drop in hemoglobin of > 5 g/dL or a hematocrit drop of > 15%.11

2.3 PCI outcomes

An independent interventionalist analyzed the outcome of the PCI. Left main coronary artery disease was defined as > 50% stenosis in the left main coronary artery; a stenosis > 70% was considered significant in all other coronary arteries. Follow-up was performed by clinical interview or telephone contact after discharge.

2.4 Endpoints

Primary endpoints were death and a composite endpoint including death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization or urgent CABG in- hospital and during long-term follow-up (1 year).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 11 statistical package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Continuous variables are expressed as means ± SE and discrete variables as percentages. Comparisons of proportions were evaluated by the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. Cumulative survival rates were evaluated with Kaplan-Meier curves and a comparison between groups was studied using the log-rank test. Associations were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

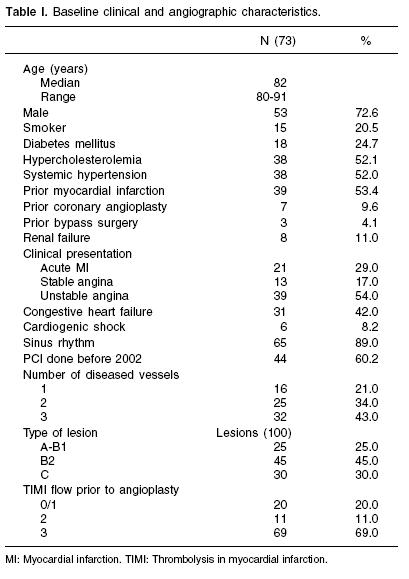

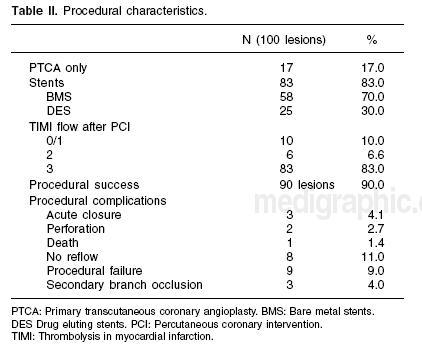

Baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics are described in Table I. Most of the patients underwent cardiac catheterization due to an acute coronary syndrome and had low left ventricular function. Most lesions were in LAD (87%) and 57% of the patients had multivessel disease. Table II shows the procedural characteristics. The most frequent type of lesions observed was B2 and C (75%). Most of the lesions (83%) were stented; bare metal stents were used in 70% of the patients.

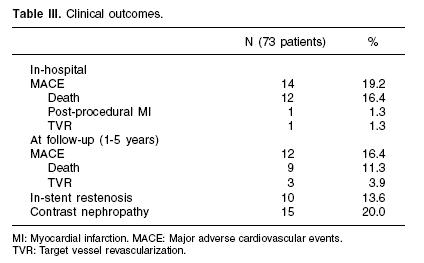

Complications during the procedure were present in 23% of the patients (Table II). In-hospital MACE was present in 19.2% and 9.6% at one year of follow-up respectively. The total mortality rate was 28.8%, however 33% of these were non-cardiovascular deaths, and only 5.6% were secondary to PCI complications (Table III). In-hospital mortality was 16.4% (12 patients). Four patients died during PCI (1 tamponade, 1 electromechanic dissociation, and 2 had cardiogenic shock). At one year of follow-up there were 6 deaths (7.8%). Five-year follow-up was completed in 35% of the patients; 3 deaths occurred during this period of time (1-5 years), and 2 had TVR due to acute coronary syndromes).

Univariate analysis is showed in Table IV. Cardiogenic shock and heart failure were strongly associated with MACE and mortality (P < 0.001) and, the presence of complete A-V Block or atrial fibrillation (AF) was also associated with both (p = 0.002 and p = 0.001, respectively).

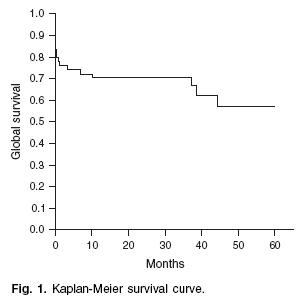

Follow-up survival time and free composite end point survival time are showed in Table IV and by Kaplan-Meier survival curves in figure 1. Among other previously known factors the presence of A-V block or AF and the presence of diabetes were significantly associated with MACE and mortality at 1-year follow-up (p < 0.05).

As describe in previous studies, the patients with just angioplasty had more incidence of in- hospital and long-term MACE and mortality than patients treated with bare metal stents and drug eluting stents (Table V).

4. Discussion

This study confirms the known predictors of mortality and MACE in this population such as cardiogenic shock, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, TIMI flow, type of lesion and, contrast nephropathy.13-19 Interestingly, the presence of A-V block or AF was strongly associated with MACE and mortality in this PCI cohort. This has been previously described in acute myocardial infarction patients undergoing thrombolysis,20-22 however, our findings support that this is a predictor of adverse prognosis even after a successful PCI. One possible explanation is that the absence of auricular contraction due to these arrhytmias decreases the atrial contribution of the ventricular pre-load, further decreasing the ejection fraction.

The mortality rate found in the present report is high (28.8% global mortality and 19% cardiac mortality compared to 3% from previous reports).7 However, most of the patients included in our series (83%) had an acute coronary syndrome a known predictor of mortality in patients undergoing PCI independently of age,2,23 especially in elderly population.3,24 Furthermore, 8.3% of the patients in this group were in cardiogenic shock, population with a mortality rate of 80% from previous reports.25 Another possible explanation for the elevated mortality is that elective PCI was only performed in 17% of our population compared with 69% in other series.5,26 The presence of diabetes mellitus is associated with in-hospital and long-term mortality. These patients tend to present with several co-morbidities such as nephropathy; this pathology has been recently associated with a higher incidence of in-hospital mortality.19 Alternative hypothesis of the higher rate of mortality in diabetics would be an increase of trans-procedural complications such as no reflow phenomenon. This clinical relevant problem tends have a higher incidence in patients with hyperglycemia.

In this small sample of patients, it is noteworthy to note we did not observe any acute, sub-acute, or late stent thrombosis despite the use of drug eluting stents in 30% of this population.

Limitations

This is a retrospective study with a limited number of patients. Multivariate analysis and propensity score analysis were not applied due to the limited number of events observed.

5. Conclusion

Although there has been significant improvement in the clinical success rate, mortality associated with PCI in octogenarians remains high. Factors associated with in-hospital and long term follow-up mortality and MACE were cardiogenic shock, heart failure, presence of A-V Block or atrial fibrillation and TIMI flow 0-2 before and after PCI. The presence of these clinical factors may help to identify patients at higher risk for PCI.

References

1. Wenger NK, O'Rourke RA, Marcus FI: The care of elderly patients with cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 109(5): 425-8. [ Links ]

2. Grines CL, Browne KF, Marco J, Rothbaum D, Stone GW, O'Keefe J, et al: A comparison of immediate angioplasty with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. The Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med 1993; 328(10): 673-9. [ Links ]

3. Guagliumi G, Stone GW, Cox DA, Stuckey T, Tcheng JE, Turco M, et al: Outcome in elderly patients undergoing primary coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: results from the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial. Circulation 2004; 110(12): 1598-604. [ Links ]

4. Pfisterer M, Buser P, Osswald S, Allemann U, Amann W, Angehm W, et al: Outcome of elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary artery disease with an invasive vs optimized medical treatment strategy: one-year results of the randomized TIME trial. JAMA 2003; 289(9): 1117-23. [ Links ]

5. Peterson ED, Alexander KP, Malenka DJ, Hannan EL, O'Conner GT, McCallister BD: Multicenter experience in revascularization of very elderly patients. Am Heart J 2004; 148(3): 486-92. [ Links ]

6. Barakat K, Wilkinson P, Deaner A, Fluck D, Ranjadayalan K, Timmis A: How should age affect management of acute myocardial infarction? A prospective cohort study. Lancet 1999; 353(9157): 955-9. [ Links ]

7. Batchelor WB, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, Grosswald R, Weintraub WS, O'Neil WW, et al: Contemporary outcome trends in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: results in 7,472 octogenarians. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36(3): 723-30. [ Links ]

8. Graham MM, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Galbraith PD, Norris CM, Knudtson ML: Survival after coronary revascularization in the elderly. Circulation 2002; 105(20): 2378-84. [ Links ]

9. Gurwitz JH, Col NF, Avorn J: The exclusion of the elderly and women from clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 1992; 268(11): 1417-22. [ Links ]

10. Lee PY, Alexander KP, Hammill BG, Pasquali SK, Peterson ED: Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2001; 286(6): 708-13. [ Links ]

11. TIMI Study Group. The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. N Engl J Med 1985; 312(14): 932-6. [ Links ]

12. Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, et al: Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronarles for Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(9): 625-34. [ Links ]

13. Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, et al: Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2003; 108(17): 2154-69. [ Links ]

14. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Karusz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, et al: National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139(2): 137-47. [ Links ]

15. Mann JF, Gerstein HC, Pogue J, Bosch J, Yusuf S: Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and the impact of ramipril: the HOPE randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134(8): 629-36. [ Links ]

16. Beddhu S, Allen-Brady K, Cheung AK, Horne BD, Bair T, Muhlestein JB et al: Impact of renal failure on the risk of myocardial infarction and death. Kidney Int 2002; 62(5): 1776-83. [ Links ]

17. Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Crump C, Bleyer AJ, Manolio TA, Tracy RP, et al: Cardiovascular disease risk status in elderly persons with renal insufficiency. Kidney Int 2002; 62(3): 997-1004. [ Links ]

18. Edwards MS, Craven TE, Burke GL, Dean RH, Hansen KJ: Renovascular disease and the risk of adverse coronary events in the elderly: a prospective, population-based study. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(2): 207-13. [ Links ]

19. Anavekar NS, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Solomon SD, Kober L, Rouleau JL, et al: Relation between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2004; 351(13): 1285-95. [ Links ]

20. Abidov A, Kaluski E, Hod H, Leor J, Vered Z, Gottlieb S, et al: Influence of conduction disturbances on clinical outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction receiving thrombolysis (results from theARGAMI-2 study). Am J Cardiol 2004; 93(1): 76-80. [ Links ]

21. Lehto M, Snapinn S, Dickstein K, Swedberg K, Nieminen MS: Prognostic risk of atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction complicated by left ventricular dysfunction: the OPTIMAAL experience. Eur Heart J 2005; 26(4): 350-6. [ Links ]

22. Meine TJ, Al-Khatib SM, Alexander JH, Granger CB, White HD, Kilaru R, et al: Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of high-degree atrioventricular block complicating acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy. Am Heart J 2005; 149(4): 670-4. [ Links ]

23. Holmes DR, Jr., White HD, Pieper KS, Ellis SG, Califf RM, Topol EJ: Effect of age on outcome with primary angioplasty versus thrombolysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 33(2): 412-9. [ Links ]

24. DeGeare VS, Stone GW, Grines L, Brodie BR, Cox DA, Garcia E, et al: Angiographic and clinical characteristics associated with increased in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous intervention (a pooled analysis of the primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction trials). Am J Cardiol 2000; 86(1): 30-4. [ Links ]

25. Carnendran L, Abboud R, Sleeper LA, Gurunathan R, Webb JG, Menon V, et al: Trends in cardiogenic shock: report from the SHOCK Study. The should we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shock? Eur Heart J 2001; 22(6): 472-8. [ Links ]

26. Mehta RH, Sadiq I, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Avezum A, Spencer F, et al: Effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention compared with that of thrombolytic therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2004; 147(2): 253-9. [ Links ]