Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos de cardiología de México

versión On-line ISSN 1665-1731versión impresa ISSN 1405-9940

Arch. Cardiol. Méx. vol.71 no.1 Ciudad de México ene./mar. 2001

Investigación clínica

Heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass in pregnant women

Cirugía de corazón con circulación extracorpórea en pacientes embarazadas

Eduardo Salazar,* Nilda Espinola,* F Javier Molina,* Amalia Reyes,* Rodolfo Barragán*

* Instituto Nacional de Cardiología "Ignacio Chávez". (INCICH. Juan Badiano No. 1, 14080 México, D.F.)

Aceptado: 6 de noviembre de 2000

Abstract

Objective: Definite data in heart surgery with extracorporeal circulation during pregnancy is limited. This report analyzes our experience in this area.

Methods: Fifteen women underwent open heart surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass during pregnancy at our institution between 1972 and 1998. Surgical procedures included valve replacement in 13 patients (12 mitral, 1 aortic), declotting of a tilting disk mitral prosthesis in one and closure, of an atrial septal defect in the remaining patient.

Results: Thirteen patients were in New York Heart Association functional class III to IV and were operated on urgently. Eight of these women had severe acute dysfunction of either a mechanical or a biological mitral prosthesis. There were 2 maternal operative deaths for a rate of 13.3%. Fetal losses resulted at the time of these maternal deaths. Fetal deaths occurred in 5 of the 13 pregnancies (38.5%) in women who survived the surgical procedure.

Conclusions: Because of the fetal risks, open heart surgery during pregnancy should be advised only in extreme emergencies. Although pregnancy per se does not increase the maternal risk, a high maternal mortality results from the emergency nature of the surgical intervention. Fetal mortality remains high.

Key words: Heart surgery. Cardiopulmonary bypass. Pregnancy.

Resumen

Objetivo: Se analiza la experiencia del Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez con cirugía a corazón abierto con circulación extra-corpórea en pacientes embarazadas. Hay poca información disponible a este respecto.

Métodos: Quince pacientes se sometieron a cirugía a corazón abierto con circulación extracorpórea durante el embarazo entre los años 1972 y 1998. En 13 pacientes el procedimiento consistió en reemplazo valvular con prótesis (12 mitrales, una aórtica), en una se practicó resección del trombo en una prótesis mitral de disco y en la paciente restante se cerró una comunicación interauricular.

Resultados: Trece pacientes estaban en clase funcional III a IV y se operaron en situación de extrema urgencia. Ocho de estas mujeres presentaban disfunción aguda de una prótesis mitral mecánica o biológica. Hubo dos muertes operatorias para una incidencia de 13.3%. En estos dos casos hubo también muerte fetal. Cinco muertes fetales (38.5%) ocurrieron en las trece mujeres que sobrevivieron al procedimiento quirúrgico.

Conclusiones: Debido al gran riesgo fetal, la cirugía con circulación extracorpórea durante el embarazo debe indicarse sólo en casos de extrema urgencia. El embarazo no aumenta el riesgo materno per se pero la mortalidad elevada es resultado de la grave situación que conduce a la intervención quirúrgica. La mortalidad fetal permanece alta.

Palabras clave: Cirugía de corazón. Circulación extracorpórea. Embarazo.

Introduction

The overall incidence of organic heart disease in pregnancy has been estimated at less than 2%.1 The frequency of the various categories of cardiac disorders in women of childbearing age, as reported from different centers, is determined by the general prevalence of heart disease in the geographic area under consideration.2-6 In industrialized countries, the declining incidence of rheumatic heart disease has resulted in an increase in the relative frequency of congenital cardiac malformations in pregnant patients.7 However, rheumatic valvular disease is still the most common cardiac complication of pregnancy comprising approximately 60% of the total number of cases.1 The incidence is likely to be higher in countries where rheumatic fever is still endemic.

Functional deterioration of patients with heart disease during pregnancy may require surgical or invasive interventions. In gravid patients with significant mitral stenosis, closed surgical mitral commisurotomy3-6 and percutaneous balloon valvotomy8-10 have been successfully used. Balloon valvotomy has occasionally been employed in pregnant patients with critical aortic stenosis.8

Open heart surgery is seldom an issue in the gravida with heart disease, even less so in those with congenital heart disease.7 However, in some cases it is apparent, from clinical and hemodynamic evidence, that the survival of the mother is threatened without the cardiac surgical intervention under cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). The literature is scarce in this area11-19 and more information is needed to permit a better assessment of the maternal and fetal risks when such surgery is performed. In this report we describe our experience with the management of 15 gravid patients operated under CPB at the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez.

Methods

Patients. The study series comprises 15 pregnant women who underwent open heart surgery in our institution from 1972 to 1998. The clinical data on the subjects are summarized in table I. The age of the patients ranged from 17 to 38 years with a mean of 26.7 ± 6.6 years. The gestational age at the time of surgery was 3 to 32 weeks (mean 17.9 ± 9.4 weeks). Thirteen patients had rheumatic heart disease (Table II). Of these, two were subjected to open cardiac surgery because of the development of acute severe mitral regurgitation during closed surgical commissurotomy or during percutaneous balloon valvotomy. Two patients had emergency surgery because of critical mitral lesions not amenable to these procedures. Eight other patients had acute complications of a cardiac valve prosthesis: five patients presented acute massive thrombosis of a tilting-disk mitral valve and three more had acute dysfunction of a mitral bioprosthesis. One additional patient had severe mitral and aortic regurgitation. All these operations were carried out in extreme emergency situations for patients in NYHA classes III to IV. Finally, two patients had congenital cardiac malformations, were in NYHA class I and II and were operated upon in the first trimester, before they were aware they were pregnant. Surgery was performed during the first trimester in seven patients and in the second trimester in six women. The remaining two patients were operated upon in the 27th and 32nd weeks of pregnancy, respectively. Surgical procedures. Open heart surgery was performed in the usual manner. Several models of bubble oxygenator were used in 11 patients and membrane oxygenators in the last four women. The different types of oxygenator employed reflect common usage at the time of surgery. Intraoperative monitoring included electrocardiogram, invasive arterial blood pressure measurement through an ind-welling radial catheter, pulmonary artery and filling pressures through a Swan-Ganz catheter, blood flow rates, nasopharyngeal temperature, and frequent sampling of arterial PO2, PCO2 and pH. Fetal Doppler ultrasonography and uterine activity monitoring were not available during surgery.

To avoid compression of the vena cava by the enlarged uterus, those patients who were operated on after the first trimester, were positioned with the right hip elevated 15 to 20 degrees. The aorta was used for arterial cannulation and the vena cava for venous drainage. All patients received heparin for a target activated clotting time (ACT) over 400 sec. Hyperkalemic, hypothermic, crystaloid cardioplegic solutions (St. Thomas) were used in all cases. Mildly hypothermic conditions (mean temperature > 28ºC) were maintained in all patients throughout the procedure. At the end of the intervention anticoagulation was reversed with protamine to achieve the basal ACT.

Bovine pericardial xenoprostheses were implanted in mitral position in nine women and in the aortic position in one. One patient was treated with débridement and declotting of a thrombosed Björk-Shiley mitral valve. Mitral mechanical valves were used in three patients (Starr-Edwards, Björk-Shiley and ATS respectively) (Table I).

Follow-up. After discharge the patients were followed at the out patient department. Obstetric care was provided in high-risk obstetrics hospitals of the city. Information about peripartum and perinatal events was obtained from the patients themselves.

Statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean + standard deviation.

Results

Intraoperative data. Measurements obtained during surgery are listed in Table III. The information was not available in case No. 1. Cardiopulmonary bypass was used during 89.1 + 31.7 min. (range 36 to 149) whereas aortic cross-clamping lasted 62.8 ± 31.2 min. (range 15 to 125 min). Non-pulsatile pump flow rates used resulted in a cardiac index of 2.3 ± 0.4 Lmin/M2 (range 1.7 to 3.1 L/min/M2). A mean arterial pressure of 67.8 ± 10.8 mmHg (range 50 to 90 mmHg) was achieved. In patient No. 10, a cardiac index of on1y 1.7 L/min/M2 was obtained which was associated with a mean arterial pressure of 63 mmHg. This patient died during surgery. Mild hypothermia was used in all cases. The mean temperature was 31.7 ± 2.1ºC. The lowest temperatures were 25 to 28.5ºC in the first seven patients and above 30ºC in the more recent cases. Finally, the pO2, pCO2, and pH remained in adequate levels during all procedures.

Maternal results. As indicated previously, the 13 women in this series who had valvular disease were admitted to the Institute after they had been in severe heart failure during several hours and went to surgery in extremely critical condition. There were two operative maternal deaths for an operative mortality of 13.3%. Patient No. 8 was hospitalized during the 24th week of pregnancy because of an alpha-hemolytic streptococcal endocarditis on a mitral duramater alloprosthesis. Antibiotic therapy was instituted on admission but on the 5th hospital day she suddenly developed acute pulmonary edema and arterial hypotension. A ruptured prosthetic cusp and multiple vegetations were found at operation. Patient No. 10 developed massive thrombosis of a mitral Björk-Shiley prosthesis during the 13th gestational week. She was operated on 5 hours after the onset of a rapidly progressing pulmonary edema. These two women could not be weaned from CPB. The remaining 13 patients survived the operation, were discharged from the Institute 7 to 19 days postoperatively and were in NYHA functional class I one year later.

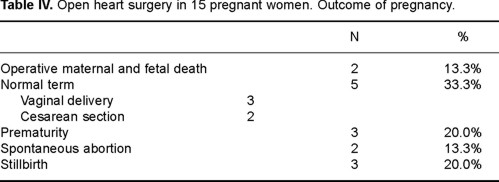

Outcome of pregnancy (Table IV). Two fetuses were lost when the patients died during operation. Fetal deaths occurred in 5 of the 13 pregnancies in patients who survived the surgical procedure (38.5%). Pregnancy ended in spontaneous abortion few hours post-operatively in two patients who were operated upon for massive thrombosis of a mitral Björk-Shiley prostheses. Stillbirths occurred in the immediate post-operative period in three women who were subjected to emergency surgery for a ruptured mitral cusp during closed mitral commisurotomy, for acute dysfunction of a bioprosthesis and for acute thrombosis of a mitral Sorin valve in the 27th, 32nd, and 24th gestational weeks, respectively. In summary, fetal deaths occurred in 6 of the 8 cases of acute prosthetic dysfunction.

Eight mothers continued their pregnancy postoperatively. Two of them received a mitral Björk-Shiley valve and were treated with long-term anticoagulation with acenocoumarol. Five patients had a bovine pericardial bioprosthesis implanted, were in sinus rhythm and required no anticoagulant therapy. Closure of an atrial septal defect had been performed in the remaining patient. Six women had vaginal deliveries whereas the other two underwent cesarean sections for obstetric indications. Prematurity occurred in three cases: pregnancy ended in the 33rd week of gestation in a patient who had been subjected to surgery for a critical mitral restenosis 8 weeks previously. The child is alive and well. Two additional patients, who had been operated on in the first trimester, for severe mitral and aortic regurgitation and for acute thrombosis of a mitral Björk-Shiley prosthesis, delivered premature babies in the 36th and 31st weeks of pregnancy, respectively. Both these infants developed a respiratory distress syndrome. Five patients carried their pregnancy to full term and delivered normal babies. Three of them had surgery during the second trimester for severe mitral disease or for acute dysfunction of a mitral bioprosthesis. The remaining two patients had congenital malformations, were in NYHA functional class I and II, and they were not known to be pregnant at the time of operation during the first trimester. Vasopressors were needed pre and intraoperatively in seven cases. Three patients received dopamine and norepinephrine whereas the remaining four women received only dopamine. One of the latter died at surgery (case No. 10). Pregnancy ended in spontaneous abortion in one of these women (case No. 12) and in stillbirth in another patient (case 14). The remaining four pregnancies resulted in liveborn babies.

Statistical analysis. In this small number of cases, the available data did not allow a meaningful analysis of the variables studied.

Discussion

Open heart surgery under CPB is seldom necessary during pregnancy. Data regarding the results of this surgery in the gravid are scarce. Early reports were usually of anecdotal cases and presumably inspired by success. A significant portion of the available information was collected by reviews of the literature or by means of surveys obtained through questionnaires sent to selected cardiovascular surgeons in which they were asked about their experience as well as for details of their cases.11-14 In 1986, Bernal and Miralles13 reviewed the literature and collected 45 cases. Maternal mortality in these early collective reviews was 1.5 to 5.0% but the risk to the fetus was substantial with a fetal mortality of 16.2% to 33%.

In 1991, Strickland et al.15 presented the cases of eight women with severe cardiac or aortic disease who were operated on under CPB during the first or second trimester of gestation. There was one fetal death (12.5%) and all the mothers survived. Rossouw and co-workers16 reported seven cases of gravid women with severe valvular disease who underwent open heart surgery. One baby was stillborn, but the others were normally delivered at full term and all the mothers survived. More recently, Pomini et al.18 collected 69 reports of cardiac surgery with CPB during pregnancy. Maternal mortality was 2.9% and fetal mortality was 20.2%. A search of the literature by Parry and Westaby19 showed 133 cases informed up to 1996. Maternal mortality was 4.3% and fetal mortality was 19%.

Published collective reviews suggest that improved medical management and surgical techniques have reduced maternal and fetal mortality in gestant women with heart disease who require open heart surgery. Thus, when Pomini et al.18 examined the last 40 cases of their collected series, maternal and fetal mortality were 0% and 12.5%, respectively. Maternal mortality would not differ from that expected in the overall population according to the type of surgical procedure performed. It should be appreciated, however, that the functional status of the patients is a prime determinant of mortality and that the surgical results are likely to be less favorable in patients who are in critical condition. Nevertheless, in their review of the literature, Bernal and Miralles13 found that 37 (80.4%) of the 46 surgical procedures in the cases they collected were carried out as relative elective surgery and only nine (19.6%) were performed in emergency situations. Because of the fetal risks involved, there should be no indication for elective open cardiac surgery during pregnancy. The exception would be an asymptomatic gravid patient with critical aortic stenosis. In young women with cardiac lesions amenable to surgery, the optimum time for elective procedures is outside of pregnancy. Open cardiac surgery in the gravida should be indicated only in patients refractory to medical therapy in whom further delay could seriously compromise their health.

In our series, maternal mortality was 13.3% and fetal wastage was 38.5%. In these cases the specific cardiac lesion and the priority of surgery obviously influenced the surgical result. Thirteen of the patients in this series were in extremely critical condition when taken to surgery. Eight of these cases corresponded to acute dysfunction of either a mechanical or a biological prosthesis. Although the clinical presentation of prosthetic dysfunction may be subacute, in many cases symptoms develop over few hours and the patients present with acute pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock.20-23 When a mechanical valve thrombosis presents as an emergency the mortality may approach 50%.21 Immediate recognition of the problem is essential to improve the outcome. Although thrombolysis has been occasionally successful in cases of thrombosis of a mechanical cardiac valve prosthesis in gravid women,24,25 this therapy has been considered a relative contraindication during pregnancy due to the maternal and fetal risk of hemorrhagic complications. In patients with acute valve thrombosis associated with cardiogenic shock and pulmonary edema, immediate surgery would seem preferable. It is generally recognized that when a prosthesis fails, reoperation is technically more difficult and carries an increased risk.22,23 In patients with prosthetic valve thrombosis, Devries et al.22 reported a total perioperative mortality rate of 12.3%,which increased to 17.5% in patients in functional class IV. The overall maternal mortality for the emergency procedures employed to treat these catastrophic cardiac pathologies during pregnancy would be expected to be high. Our results are similar to those informed by Born and his group.26 They recently reported a maternal mortality of 13.3% in 30 cases of pregnant women operated upon for rheumatic valvular disease under CPB. Their patients were in NYHA classes III and IV.

The risk to the fetus has been related to the unphysiologic and potentially harmful effects of CPB.18 Fetal mortality, which was 38.5% in our study, may also have been adversely affected by the emergency nature of the surgical intervention and the critical and unstable maternal status. Thus, six of the eight pregnancies complicated by mitral prosthetic dysfunction resulted in fetal loss. Born et al.26 also reported a fetal mortality of 33.3% which was related to prolonged surgical time and to maternal complications such as peri-operative hemorrhage.

The technical aspects of CPB in the pregnant patient have been detailed in several recent reviews.18,19,27 Cardiac surgery under CPB in pregnant patients can be made safer for the fetus by avoiding perfusion hypothermia, by the use of short perfusion times, high flow rates and pressure and by avoiding vasopressors. As noted before, the small number of cases in this series precluded an analysis of these variables in relation to either fetal or maternal mortality. Unfortunately, complicated valve operations frequently require a prolonged period of perfusion. Mildly hypothermic conditions were maintained in the patients of this series. A mean cardiac index of 2.3 L/min/m2 and a mean arterial pressure of 67.8 mmHg were achieved. It has been indicated that, during surgery, the cardiac index should be maintained in at least 2.5 L/min/m2 and that a mean arterial pressure of 70 mmHg or greater may be necessary.15,27 Finally, despite their effects on placental perfusion, inotropic drugs are often required in these critically ill patients. Fetal Doppler ultrasonography and uterine activity monitoring15-19,27 should be used during surgery to allow the necessary adjustments of flow to ensure adequate perfusion of the fetoplacental unit. Our institution is a tertiary care hospital devoted to cardiology where these monitoring facilities are not readily available.

Open heart surgery in the third trimester of pregnancy may be managed by cesarean section followed by the cardiac procedure under CPB.19 Strickland et al.15 reported the cases of two women who had cesarean sections performed immediately before surgery in the 30th and 35th weeks of gestation, respectively. Both infants were live born but one of the mothers died intraoperatively. In the case reported by Westaby et al.28 a cesarean section was performed with the chest open ready for cannulation in a women who underwent emergency aortic valve replacement for prosthetic valve endocarditis. A 19 year old woman, not included in our series, was admitted to the Institute in severe heart failure due to mitral stenosis and regurgitation, during the 34th week of pregnancy. A live born infant was delivered by cesarean section. The clinical status improved on medical management and a mitral bovine pericardial prosthesis was successfully implanted one week later. It would appear safer to deliver an infant at 28 weeks or more in preference to exposing the fetus to the risks of CPB.19

Conclusion

Because of the risks of CPB to the fetus, open heart surgery during pregnancy should not be advised except in emergency cases. Maternal mortality does not appear to be affected by pregnancy. It is rather related to the basic cardiac lesion, to the functional status of the heart at the time of surgery, and to the specific surgical procedure performed. The overall maternal mortality for emergency surgery in these critically ill patients would be expected to be high. Fetal mortality remains high and is increased by the unstable hemodynamic status of the mother. Whenever possible, delivery of the child before commencing CPB is a preferable option. The principles of CPB to be used during pregnancy are high pressure-high flow, normothermia and fetal heart and uterine contractions monitoring.14,18,19,27

References

1. MCFAUL PB, DORNAN JC, LAMKI H, BOYLE D: Pregnancy complicated by maternal heart disease. A review of 519 women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988; 95: 861-867. [ Links ]

2. EISENBERG MJ: Rheumatic heart disease in the developing world , prevalence, prevention, and control. Eur Heart J 1993; 14: 122-128. [ Links ]

3. SZEKELY P, TURNER R, SNAITH L: Pregnancy and the changing pattern of rheumatic heart disease. Br Heart J 1973; 35: 1293-1303. [ Links ]

4. STEPHEN SJ: Changing patterns of mitral stenosis in childhood and pregnancy in Sri Lanka. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19: 1276-1284. [ Links ]

5. VOSLOO S, REICHART B: The feasibility of closed mitral valvotomy in pregnancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987; 93: 675-679. [ Links ]

6. PAVANKUMAR P, VENUGOPAL P, KAUL U, IYER KS, DAS B, SAMPATHKUMAR A, ET AL: Closed mitral valvotomy during pregnancy. A 20-year experience. Scand J Cardiovasc Surg 1988; 22: 11-15. [ Links ]

7. PERLOFF JK: Congenital heart disease and pregnancy. Clin Cardiol 1994; 17: 579-587. [ Links ]

8. PRESBITERO P, PREVER SB, BRUSCA A: Interventional cardiology in pregnancy. Eur Heart J 1996; 17: 182-188. [ Links ]

9. IUNG B, CORMIER B, ELIAS J, MICHEL PL, NALLET O, PORTE JM, ET AL: Usefulness of percutaneous balloon commissurotomy of mitral stenosis during pregnancy. Am J Cardiol 1994; 73: 398-400. [ Links ]

10. MARTÍNEZ-REDING J, CORDERO A, KURI J, MARTÍNEZ-RIOS MA, SALAZAR E: Treatment of severe mitral stenosis with percutaneous balloon valvotomy in pregnant patients. Clin Cardiol 1998; 21: 659-663. [ Links ]

11. ZITNIK RS, BRANDENBURG RO, SHELDON R, WALLACE RB: Pregnancy and open heart surgery. Circulation 1969; 39 and 40 (suppl I): 1257-1262. [ Links ]

12. BECKER MR: Intracardiac surgery in pregnant women. Ann Thor Surg 1983; 36: 453-458. [ Links ]

13. BERNAL JM, MIRALLES PJ: Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass during pregnancy. Obst Gynecol Survey 1986; 41: 1-6. [ Links ]

14. SULLIVAN HJ: Valvular heart surgery during pregnancy. Surg Clin N America 1995; 75: 59-75. [ Links ]

15. STRICKLAND R, OLIVER WC, CHARNTIGIAN RC: Anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, and the pregnant patient. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66: 411-429. [ Links ]

16. ROSSOUW GJ, KNOTT-CRAIG CJ, BARNARD PM, MACGREGOR LA, VAN ZYL WP: Intracardiac operation in seven pregnant women. Ann Thorac Surg 1993; 55: 1172-1174. [ Links ]

17. CHAMBERS CHE, CLARK SL: Cardiac surgery during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1994; 37: 316-323. [ Links ]

18. POMINI F, MERCOGLIANO D, CAVALLETTI C, CARUSO A, POMINI P: Cardiopulmonary bypass in pregnancy. Ann Thor Surg 1996; 61: 259-268. [ Links ]

19. PARRY AJ, WESTABY S: Cardiopulmonay bypass during pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg 1996; 61: 1865-1869. [ Links ]

20. EDMUNDS LH. Thrombotic and bleeding complications of prosthetic heart valves. Ann Thorac Surg 1987; 44: 430-445. [ Links ]

21. HAUSMANN D, MUGGE A, DANIEL WG: Valve thrombosis: Diagnosis and management. In: Butchart EG, Bodnar E, editors. Thrombosis, embolism and bleeding. London: ICR Publishers, 1992: 387-401. [ Links ]

22. PAVIE A, BORNS B, BAUD F, GANDJBAKHCH I, CABROL C: Surgery of prosthetic valve thrombosis. Eur Heart J 1984; 5 (Suppl D): 39-42. [ Links ]

23. DEVIRI E, SARELI P, WISENBAUGH T, CRONJE SL: Obstruction of mechanical heart valve prostheses: clinical aspects and surgical management. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 17: 646-650. [ Links ]

24. FLEYFEL M, BOURZOUFI K, HUIN G, SUBTIL D, PUECH F: Recombinant tissue type plasminogen activator treatment of thrombosed mitral valve prosthesis during pregnancy. Can J Anaesth 1997; 44: 735-738. [ Links ]

25. TURRENTINE MA, BRAEMS G, RAMÍREZ MM: Use of thrombolytics for the treatment of thromboembolic disease during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Survey 1995; 50: 534-541. [ Links ]

26. BORN D, MASSONETTO JC, MARCONDES DE ALMEIDA PA, FERNANDES MORON A, BUFFOLO E, GOMES WJ, ET AL: Cirurgia cardíaca com circulaçao extracorpórea em gestantes. Análise da evaluçao materno-fetal. Arq Bras Cardiol 1995; 64: 207-211. [ Links ]

27. COHEN RG, CASTRO LJ: Cardiac surgery during pregnancy. In: Elakayam U, Gleicher N, editors. Cardiac problems in pregnancy. 3rd edition. Wiley-Liss Inc 1998: 277-283. [ Links ]

28. WESTABY S, PARRY AJ, FORFAR JC: Reoperation for prosthetic valve endocarditis in the third trimester of pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg 1992; 53: 263-265. [ Links ]