Introduction

The rise of ever more sophisticated, ubiquitous and easily employed Information and Communications Technology (ICT) has altered the relationship between people and the space they inhabit, as well as the very way life in cities is led. Concomitantly, the growing complexity of cities has resulted in new challenges for urban management, and the search for new solutions such as the use of technologies broadens the understanding of local challenges hitherto invisible, or delayed due to a lack of such tools.

This new urbanism, created by the interaction between cities and technologies, aims to translate the complexity of relations that challenge the traditional notions of place (Amin and Thrift, 2002). Over the years, several authors have tried to explain the relationship between technologies and the urban space, establishing different terminologies in the process, such as virtual cities (Eisenberg, 1999; Donath, 1996), digital cities (Aurigi, 2005; Schuler, 2002) and cyber cities (Boyer, 1992; Gandy, 2005).

In this context, the term smart city emerged as a concept which in turn came to define cities that make use of technologies to update, automatize or improve systems and services (Aldairi and Tawalbeh, 2017; Llacuna et al., 2015). In time, such a phenomenon came to encompass a plethora of different perspectives. Thus, there is no single definition for the term, or even a general consensus established in the current literature on the topic (Angelidou, 2014; Albino et al., 2015, Aldairi and Tawalbeh, 2017; Bibri and Krogstie, 2017; Cassandras, 2016).

Therefore, the smart city phenomenon is currently being analyzed in multiple understandings, generating debates around matters of urban resilience, adaptability, entrepreneurship and governance. One of the most important factors stemming from this discussion is the question of citizen participation and the need for their empowerment through the use of ICTs. This process may also result in confidence in the relation between the government and its citizens.

Granted, technology generates a series of possibilities; it is not a primal aspect of technology to provide the automatic capacity to create smarter communities, but rather to create adaptability and empowerment conditions for society, through the use of technology with social and educational goals, as well as in political discourse (Hollands, 2008). Several cities have been implementing systems vying for greater integration between municipal sectors, for the optimization of services and improved relations between government and citizens.

This document previewed a decentralized administration model, with greater incentive for popular participation supported by municipal master plans. Moreover, it was from that moment on that matters related to the role of technologies in society were raised, as was the case in international case studies (Ultramari and Firkowski, 2012).

The case to be discussed in this paper, as an example of an integration action between public government and citizen is an initiative originated in 1984 in the city of Curitiba, in the South part of Brazil: the 156 Central (Central 156), a call center established to provide a direct means of communication between citizens and City Hall. This case is considered particularly relevant for the academic field for two reasons: a) it is a fairly innovative endeavor at that time, the 80’s, in Brazil - also as an emblematic case, taken as an example or reference for another cities; b) This project represents a characteristic of the city, as a part of the internationally recognition by tradition in innovative urban planning.

The city of Curitiba proved to be especially relevant in this field over the last decades, as an renowned example of innovations in urban planning, reflected in measurable gains for city management. The city, whose current population is estimated at more than 1.9 million inhabitants (IBGE, 2018), began its tradition of modernity planned and experienced in urban planning in the 1970s, in a time of strong belief in the power of architecture to order territories and transform social contexts (Souza, 2001). The directives of the Master Plan foreseen at that time aimed to guide the city’s growth process from three axes of action: Land Use, Collective Transportation and Road System (IPPUC, 2018). The plan for urban mobility and the preservation of green areas, associated with these measures, have become the main urban characteristics of the city. Over time, these actions have formed an urban identity capable of attracting specific tourism and being replicated in other cities around the world. Central 156, therefore, appears in a context of active concern with innovation in urban planning. The Central is currently located in the Curitiba Institute of Informatics (ICI), now known as the “Smart Cities Institute”. This call center, working 24/7, enables citizens to request information on urban services (such as the public transportation system itinerary), as well as demand actions (such as waste collection in specific cluttered streets) and ask for information on documents, tourism, events, cultural attractions and more. It was a successful case which served as a model for many other cities in Brazil, such as Itabuna (in Bahia), Araucária (in Paraná) and Teresina (in Piauí) (ICI, 2014; 2016; 2017), and it is still an ongoing project in Curitiba, even after several elections and consequent changes in City Hall management.

Even though the system has been updated over time, encompassing website and chat communications as well, the call center is still quite used by locals and tourists alike, becoming a significant element in increased trust between citizens and municipal government.

Such is the scenario which forms the background for this article, leading to the following question: how can the 156 Central be considered a process of increased urban smartness in the city of Curitiba, taking into account the fact that it is an essentially analogic tool that continues to be of use to the citizens even though more advanced ICTs have arisen?

Thus, the main goal of this article is to analyze the communications process between management and citizens in the city of Curitiba, using the concepts of smart cities and trustworthiness, based on the experience of the 156 Central. It was also crucial to address the following:

i) outline the history of the 156 Central initiative of management/ citizen communications, analyzing empirically the context of management/citizen communications in Curitiba through that initiative;

ii) characterize the participation of citizens in the process of trustworthiness generation through such projects;

iii) identify contributing factors to the continued use of such an analogic tool, even faced with the rise of ever more advanced technologies, such as apps, social networks, live video chats etc., as well as factors that may undermine the communication process through this tool.

The present article is organized in such a way as to report, first, the concept of smart city and correlated factors, such as communications between management and citizens, popular participation and trust generation. Second, the methodology is outlined, followed by the research results, specifically structured to discuss and provide an analytical connection with the object of the study (Curitiba City Hall’s 156 Central). Lastly, the conclusions are presented at the end of the article.

1. Smart cities

Current literature on smart cities does not pinpoint with exact precision the genesis of the term, but there seems to be a consensus regarding its first use in the 1990s, with the rising influence of ICTs (Komninos, 2011; Llacuna et al., 2015; Albino et al., 2015).

One of the definitions for the term states that smart cities are cities that present several sociotechnical consequences and spatial effects stemming from interconnections created by digital instrumentation. They do not represent, however, the imaginary cities of the future, but rather dense and complex urban networks that may be managed, regulated and monitored with the use of technologies (Kitchin, 2014). The concept of smart city operates on the base premise of hyperconnectivity between people, data, processes, machines and ubiquitous computing, which in turn reinforce the participation of citizens as sensorial agents and information providers (Llacuna et al., 2015). In other words, smart cities are based on the concept of urban sensing, where services and solutions have a strong participation in technology (Abella et al., 2015).

In this sense, a smart city consists of two main forces: technology, which constantly pushes for new solutions for society, creating the offer independently of a need for it, and demand, which drives new solutions according to local necessities (ngelidou, 2015).

Factors such as sustainability, urban resilience, creativity and entrepreneurship have gained increased importance in the definition of smart cities. Terms like sustainable smart cities (Bibri and Krogstie, 2017; Al-Nasrawi et al., 2015), collective creation (Fanaya, 2016), resilient city (Godschalk, 2003) and sensitive city (Santaella, 2014) broaden the scope of our current understanding of the smart city phenomenon.

Divergence arises due to the multiple interpretations the concept allows for, making it a difficult task to label a city as smart, as the term may be used to refer to any project using digital tools. It is often unclear what exactly is being improved with the action of making a city or process smart (Calzada and Cobo, 2015), but there seems to be greater acceptance of so-called smart city strategies throughout the world in the last few years, mainly due to changes in the purpose of urban governance in the information era (Barns et al., 2016).

In Brazil, the use of the term smart city has been recurrent in projects sponsored by foreign companies or developed via public-private partnerships. It is common to find projects presenting narrow scope, with relatively few exploring a broad vision of smartness in city operations. The propagation of the concept also occurs at fairs and exhibits, where the term is often associated with the automobile, construction, startup and electronic government industries.

It becomes clear that there is a series of relations that may be established between the term smart city and the urban space; this article, however, focuses on interactions between citizen and government. This will be done in sense to analyze the polical factors involved, indentifying which are the interested and the related parts with the smart city concept (Barns et al., 2016).

1.1. Data and demand management: interactions between citizens and management

Smart cities may be considered those that explore the potential of Big Data - a large volume of data characterized by speed and variety (McAfee; Brynjolfsson, 2012) - to consume and distribute information, guiding the actions of public and private administrators and helping in decision making processes (Lemos, 2013a).

The interoperability of data and systems is a fundamental part of the smart city concept (Avelar et al., 2015). Moreover, the level of security for the data determines the level of smartness of a city, especially regarding the use of surveillance footage, violation of privacy and protection of identities. The relevance of the data in question is in the possibility of combining the collected information in numerous ways, helping city management and public service optimization (Kanashiro et al., 2013). In this sense, people have also become information providers, resulting in Big Data fed by transportation and mobility information (Lemos, 2013b).

In this process, one must consider the fact that cities have been increasing the scope of their open data policies. Open data are public or private data legally regulated and released in legible format by machines, with no access restrictions. The opening of data promotes greater citizen engagement and attention to their surroundings; therefore, it is a governmental initiative for increased transparency. Information is also important for promoting integration between sectors, even if it is done exclusively out of a need for managing the data jointly (Barns, 2016).

The integration aspect not only contributes in terms of organizational communications, avoiding scarce resources being wasted in doubled services, but also helps lowering possible information inequality between agencies (Odendaal, 2003). Thus, managing data becomes a challenge for smart cities, as it is a process dependent on governmental arrangements (Barns et al., 2016). Organizational integration is, therefore, essential so that technologies may contribute effectively for improving local governance.

In the heart of this discussion, the question of citizen participation as a central element for establishing so-called smart cities arises. ICTs are used in this process to overcome certain limitations of traditional popular participation methods (Sæbø et al., 2008), also helping reorganize processes and reduce bureaucracy (Toppeta, 2010). Current literature highlights the sum of bottom-up and top-down actions as a factor for success, acting not exclusively but in a complementary manner. The bottom-up movement supports smart cities, as it ensures effective citizen participation in city management, developing local knowledge. There seems to be a growing number of voices demanding the smart city approach go beyond the technology pushed by the market and actively embrace participation, citizen engagement and bottom-up perspectives (Galdon-Clavell, 2013; Komninos, 2007).

1.2. Cooperation and trust

Trust between the subjects involves learning before interests, sociability and the law (Caillé, 1994). In this sense, trust is not something that can be created, but rather arises in the beginning of a relationship and becomes a previously established condition for any subsequent interaction (Sabel, 1992).

Authors Sako (1998) and Lane and Bachmann (1996) categorize trust in terms that may be applied to city management. According to Sako (1998), there are three trust categories that may also be considered in city management processes:

a) contractual trust, through which rules are established bilaterally via written commitments;

b) competence trust, in which mutual hope exists that the other party will fulfill their end of the commitment;

c) “good will” trust, in which mutual hope exists that the other party will address a large number of different demands and take initiative with the goal of exploring new opportunities that may provide mutual benefits.

For Lane and Bachmann (1996), trust may be established:

a) based on processes, in which the relationship proves to be stable over time, leading to the conviction that the other party will continue to express their usual behavior;

b) based on characteristics, considering common ground between the parties, such as family and religious relations;

c) based on institutions, which in turn are tied to the existence of formal structures in society, such as the judicial system, government and organizations. This kind of trust cannot simply be established by trust in individual behavior, but depends on the position at the organization and its structure and modus operandi.

In a trust relationship, expecting from the other party acceptable behavior in unforeseen circumstances becomes more important than knowing the other party’s behavior in usual situations. Behavioral predictability results in interactive learning processes among partners. This learning between individuals and companies allows for common interpretation in unexpected situations, and, consequently, favors the establishment of a consensual strategy for implementing a mutually acceptable answer should course correction or the revision of the established rules prove necessary (Sako, 1998).

A smart city is the result of the combination of human, institutional, educational and technological capacities, which demand cooperative action. Hence, working on trust and cooperation between urban subjects may lead to improvements in public services and general social wellbeing (Komninos, 2007).

2. Methodology

This research aims to characterize the citizen/management communications process in the city of Curitiba, using the concept of smart cities and the practical experience of the 156 Central. The choice of this particular initiative is justified due to its representativeness, built over time so that it became an essentially analogic tool (telephone-based) for communications between citizens and city management which continues to be used even though more updated and advanced technology has arisen. In order to fulfill this objective, three distinct methodological phases were carried out, namely: documental research, in-depth interviews and statistic analysis.

2.1. Validating the one-case research

In order to confirm the choice of case 156 as relevant and emblematic, a survey was carried out in all 27 Brazilian capitals, in order to identify which ones use tools to communicate with citizen. In this phase data were searched on the official sites of city halls from the combination of the following keywords: name of the capital, customer service center (or citizen call center), year of implementation (number).

The results of this phase pointed to a national panorama in which, among the 27 capitals, only four did not have any type of integrated system in that format. Although in several cities the communication is made through different channels of communication, six of them have a 156 system: besides Curitiba, also Salvador (north-east region), Goiânia (Central West region), Vitória and São Paulo (Southeast region), and Porto Alegre (South region). These are geographically distant cities with very different population demands and characteristics, so the multiple case study option became unfeasible for the paper format. In addition, the research showed that there is a reference process of these cities in relation to the project of Curitiba, which makes the case even more relevant. Some of the capitals researched will, however, be briefly presented in the case analysis, as a way of composing a broader scenario.

2.2. Searching for Curitiba 156

In a first moment a research was conducted on the Curitiba City Hall Website and in four news websites (G1, O Globo, Folha de São Paulo and Gazeta do Povo), selected due to their local and national relevance. Document research allows for the mapping of specific social, cultural and historic contexts (Sá-Silva et al.,2009). In this sources, the search was carried out with the key words “collaborative communications” and “communiations in smart cities”, linked to the word “Curitiba”. The search resulted in a research corpus1 composed of nine news articles available on the City Hall Website and in the news media. A second research phase consisted in interviews carried out with three subjects - two technicians from Curitiba City Hall and one ICI (where the 156 Central is located) agent - in order to obtain information on the Central. The goal of interviewing is to verify what the researched subject knows, thinks and argues (Severino, 2017).

These interviews are a part of a broader research aiming to understand the smart city phenomenon in Brazil. In regards to the text itself, the subjects were questioned on what are their particular impressions of the projects implemented in Curitiba that may be considered smart city projects, with special attention paid to comments on the 156 Central. The third research phase consisted in gathering and analyzing statistics for empirical evaluation of the results in collaborative communications over time in Curitiba. In this phase, data collection took place over two stages. First, through the data provided by the Service Management sector in the ICI itself. The institution provided material with service data regarding the 2001-2017 period (up to December), categorized according to service type and profile of the serviced citizens.

A second stage further analyzed this information in terms of geographic specificities and types of demands. In order to accomplish that, the authors made use of the data available in the Curitiba City Hall Open Data Platform regarding the demands received by the 156 Central. The platform presents charts kept by an influx of service protocols from the Central, as well as other data relative to the many different municipal secretariats. For statistic purposes, it was determined that only data of over a year of work in the 156 Central would be used. Thusly, charts were selected from the last backup available (October, 2017), consisting in data from 921,897 service protocols carried out between June 1st, 2016, and July 17th, 2017. The data was categorized according to the type and origin of the demand, in order to verify the ways the population appropriates the service.

Data analysis was carried out via a simplified content analysis of the interviews and by categorizing the information according to geographic and temporal limiting and demand typology, resulting in the graphs and maps presented in the following section. After identifying the main factors of influence over the services of the 156 Central, these factors were then linked to the theoretical premises previously discussed in this article. The result of this process was a summary chart presented in item 4.3, which encompasses the conclusions of this research.

3. Results analysis

The results presented below are divided into categories for better fulfilling the goals of this research. Hence, the history of the 156 Central is presented first, followed by a discussion of the main characteristics of this initiative as a citizen/management communications strategy, in which the matters of trust and fragility are analyzed.

3.1. Brazilian context of 156 Centrals: From Curitiba to Brazil

The Curitiba 156 Central is a platform created in 1984 with the goal of providing information to the citizen and reducing waiting lines in municipal institutions’ service stations. At the time, the information was restricted to consultation on services and permits. From 2002 onwards, the Central began to operate on the 24/7 model, rotating over 100 employees (Portal G1, 2017a). Currently, the Central integrates every municipal secretariat to offer more numerous and varied information. In the last years, the Platform has also gained a website and mobile app version, with an interactive menu where requests can be made directly via chat.

In relation to the 27 Brazilian capitals, Curitiba is the oldest project, followed by Porto Alegre which has this system implemented in 1985. The design has become an expressive instrument of integrated management between citizen and public power, since it integrates several services and procedures. This occurs since the arrival of information (demand), following-up on the progress of the request (including allowing the citizen to consult the development of the process), the search for the solution and involvement of higher departments gradually involved in each case. Finally, when the process is “closed”, the citizen receives a consultation link to inform the level of personal satisfaction with the resolution of the demand. The process becomes a database with statistic sampling relating urban problems and their solutions, which is available for verification in the open data portal.

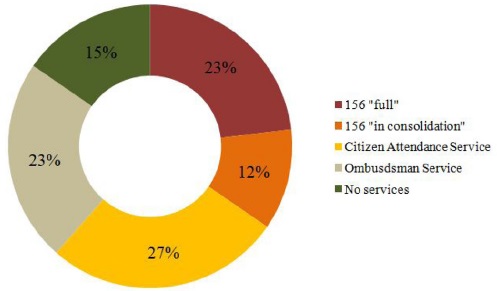

Currently, most of the Brazilian capitals have some citizen service, but these are presented with different levels of complexity in the services and with different stages of implementation and actuation. This research consider this by the prism with four different categories (Figure 1): a) the “156 full” experience, that is in the same format of the service offered in Curitiba; b) the experience “156 in consolidation”, which seeks to reach this point, but still in the implementation phase, only to attend specific urban sectors (for example transportation or urban reforms, which is present on three capitals; c) a common citizen attendance service, not necessarily via integrated communication channels; and d) the ombuds-man service, or a simple communication channel where the citizen presents his demands, but without guarantee of return.

Source: own elaboration based on data collected from governmental sites of the Brazilian capitals, according to the methodology.

Figure 1 Distribution of 156 cases in Brazilian Capitals, by categories

What is considered as “156 full” initiatives are more recent cases that arose, in the majority, after the years 2000. This reinforces the importance of the case of Curitiba, since the other capitals used this pioneer experience as inspiration. In the case of the city of Porto Alegre, in particular, the reference was used immediately, since only one year separate one and another initiative. This reinforces the influence of the case of Curitiba in the southern region of the country, considering the broad context and socioeconomic characteristics of the region.

Most of the consolidation on 156 model services occurred in the year of 2011, a period that may be related to the growth in the use of ICT in public services and the dissemination of the concept of Smart City as a way of solving urban problems. In these more recent cases the services are already associated with contemporary tools such as digital apps, whatsapp and social networks. This is interesting considering the Curitiba case as more “analogical” in terms of the tools used, although it also seeks to follow the updating structure with digitally offered services.

3.2. 156 Central: demand characterization

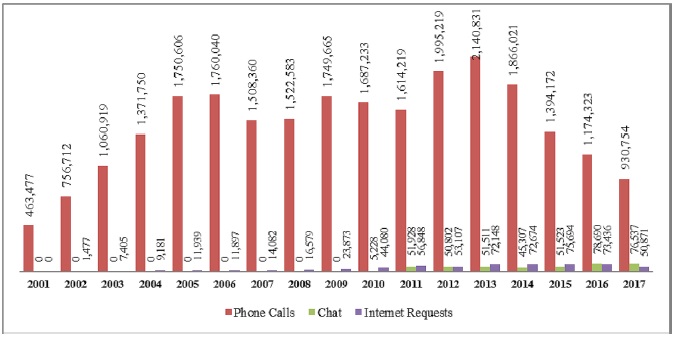

According to the data provided by the ICI, 51,043,925 demands were received and serviced from 2001 to 2017. Figure 2 presents the number of services provided in this period according to the communication tool through which requests were made.

Source: own elaborations based on ICI data.

Figure 2 Distribution of requests on the 156 Platform, between 2001 and 2017, by means of communication

The figure shows that although the number of chat and internet requests has grown (especially from 2009 onwards) it is still a much less used means of communicating with the Central than phone calls, a surprising finding as it highlights the citizens’ overall preference for the analogic service. This result seems to suggest that even if there is a trend showcasing the growth in the use of other means of communication, the 156 Central is still solidly a call center, a tool that the citizens have continued to actively embrace and use.

The figure also shows the number of phone-based demands varies greatly over the years. It can be observed that there are slight spikes in servicing in the beginning of each new four-year municipal management cycle (2005, 2009 and 2013), periods in which the political groups in charge of City Hall changed. This may hint at two conclusions: a) that the citizen is uncertain of the continuation or lack thereof for certain urban projects when faced with a new city management scenario, resulting in a need for more information related to their day to day activities; b) it may also suggest that the citizen takes advantage of the change in political power to make his or her demands.

The figure also presents a decline in the number of services since 2013. According to Interviewee 01, this decrease may have happened due to three main factors:

a) “Competition” with other technologies, especially social media. An emblematic example is the Curitiba City Hall Facebook Fan-page, with over 860,000 followers as of december, 2017, a tool which has become an example for change in language and communications between City Hall and the population. In this page, the City Hall communications team posts news and articles on construction works, projects, the weather, general warnings and cultural attractions taking place in Curitiba. Moreover, it also answers citizens’ questions and requests. When doubts, complaints or suggestions are posted, answers come rapidly (Santos and Harmata, 2013). In 2015, the initiative was classified first in the Customer Service 2.0 category on Share, Brazil’s most important award in the social media field. The Customer Service 2.0 category justified its choice due to the Curitiba City Hall’s swift responding capabilities. At the time, maximum reply waiting time for messages sent on Facebook was 38 minutes (Prefeitura Municipal de Curitiba, 2015):

b) Low efficiency in problem solving: the number of requests tends to drop when the citizen informs city management of a problem and does not receive a solution in return, resulting in lowered trust between the citizen and the service. This factor is also linked to the economic crisis which Brazil has been facing since 2014, resulting in lowered budget for the Curitiba City Hall - and, consequently, reduced capacity for servicing the population and solving civilians’ demands.

c) External factors, such as the matter of the deintegration of the public transportation network. Since 2012, the Curitiba public transportation system, which previously linked all cities in the Metropolitan Area, was deintegrated. After that, citizens no longer had a need to demand information on transportation (schedule, itinerary, complaints etc.) at the Central directly, and began to make these demands to the responsible departments in their specific cities in the Metropolitan Areas.

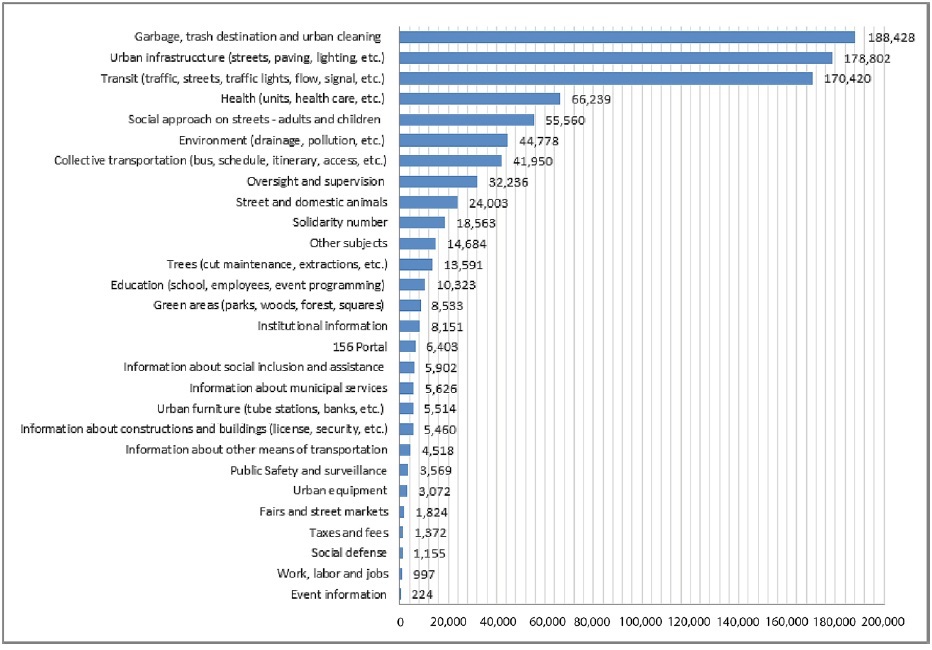

For greater depth in the discussion, data from the 156 Central was also analyzed according to the topic of the demands. As per the research conducted, 891.297 protocols were registered, classified in over 200 categories, which were in turn summarized in this analysis for a more streamlined understanding.

The largest number of requests (over 188,000) are related to waste collection and public cleaning (Figure 3). In second and third place, respectively, are demands for urban infrastructure (paving, public lighting, etc.), and traffic (traffic jams, flow, street lights, signs, etc.). The Central already has a specific menu for these three categories, in order to speed up customer services. The matter of social street actions is also significant, with over 55,000 requests made over this period; in this case, citizens contact the Central to inform city management on people living in homelessness and in need of shelter and/or help.

Source: own elaborations based on 156 open data of Curitiba Municipality.

Figure 3 Distribution of requests on the 156 Platform, between June 2016 and August 2017, by topic

The data shows that most requests receive feedback, which may be immediate response to a question or later feedback on the ongoing development of a request. This return may be sent directly to the person via e-mail (55,8%), informed via phone call (22,9%) or even in person, although rarely (0,1%). In the period analyzed, roughly a fifth of requests (21,9%) did not receive any kind of feedback.

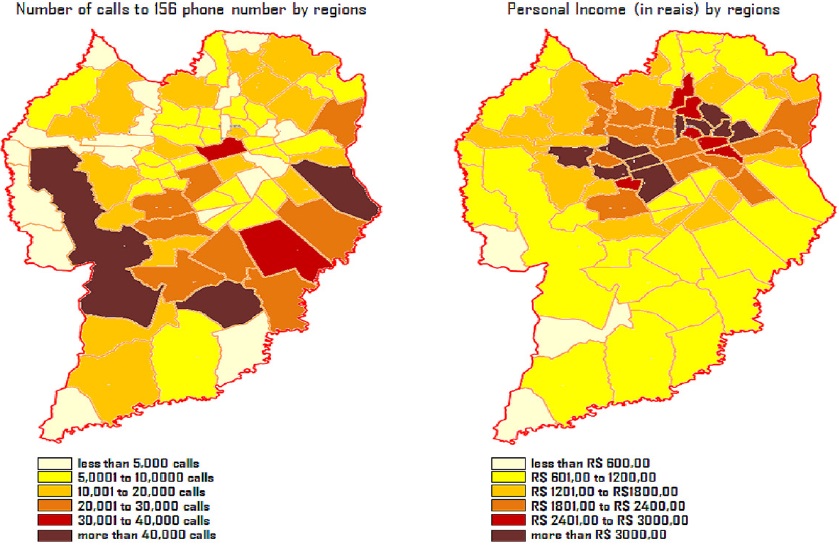

The data set was also analyzed regarding the distribution of requests in each of the 75 regions of Curitiba. A tendency of concentration in the outlying neighborhoods, especially in the South area, can be observed. The analysis was carried out with the goal of identifying possible causes behind this trend; the distribution map for the number of requests was compared to the map of average income per capita (over 10 years old) (Figure 4).

Source: own elaborations bsed on 156 open data of Curitiba Municipality (IPPUC, 2015) and (IBGE, 2010). Elaborated on Image edition software and Autocad.

Figure 4 Comparison between number of requests and personal income after 5 years old, by region

It can be concluded that it is a dichotomy between these two variants. There is a tendency for greater concentration of citizen/government communications in regions with a lower per capita rate. This reveals a demand-accessibility relationship that suggests that this user profile may have more adherence to an analog communication channel, which may reflect, perhaps, also in a smaller accessibility to other channels of communication with the city hall. In this same context, in neighborhoods with greater purchasing power there are fewer demands, and there may be greater access to other means of communication with the municipal government - not just the service 156.

Another interesting aspect to consider is: over the years a relationship of trust has been built around the service, which reflects in the appropriation of the tool by the population and what will be better discussed in the next item.

3.2. Management/citizen communications and the generation of trust

The 156 Central came, in time, to be recognized as a successful management tool for citizen/management relations, serving as an inspiration for projects in other cities, as mentioned before; nevertheless, some criticisms are aimed at the service.

The positive outlook on the service itself may be found in the discourse of different subjects, as outlined in the excerpts below:

“I always call 156 and they answer quickly. I tell my neighbors to call them as well.” (Curitiba resident, in a statement made to the Curitiba City Hall).

“When a lamp from the Curitiba public lighting system goes out or presents technical failure, it takes an average of two days for city management to address the problem. Swiftness in servicing the population is due to the computerized systems used by the Public Lighting Department, developed by engineers from the Public Works and Infrastructure Secretariat and a technology company. […] The maintenance manager at the Secretariat […] explains that the service to the citizen used to take longer. ‘Before implementing the computerized system, citizens called 156 and the information needed to be printed out to get to us so we could categorize it. This used to take two days. Now, the whole maintenance service, from request to fixing, takes 48 hours’.” (Prefeitura Municipal de Curitiba, 2017).

“[…] an example begging to be copied, adapted and modeled after […], which has been in place since the 80s […] in Curitiba. […] is fantastic: it has great acceptance rates among the residents of Curitiba. It’s a gateway for the citizen, for the taxpayer to reach City Hall. It’s there - whether it’s by phone, website or smartphone app - that the citizen can solve absolutely anything; they can talk to City Hall, and most importantly, receive an answer as to when their problem will be addressed. And they have deadlines […]. According to the 156 service, they have goals to reach, deadlines to respect. […] Now, what is expected, which is fundamental for a service of this magnitude, is good training […]” (Portal G1, 2017a).

“It’s a level of service that is a reference in Brazil. […] Resolution times are monitored: if the deadline is not met, upper levels of management are sequentially responsible for finding out why. Then, all these services requested by the citizen are monitored by management; following that, there’s the knowledge regarding what the demands of the population are, as well as the setbacks for service solving, lack of infrastructure to solve the problems society is demanding be solved. Thus, it is a great thermometer for the demands and needs of the population. It is also a great channel for communication, which brought, in a pioneering way, the citizen to public management - one of the cornerstones of smart cities.” (Interviewee 02).

The service, however, has also been the target of complaints by some users. According to Portal G1 (2015), one of the negative effects is that the user is charged for the phone call. Currently, citizens are advised to use the online services to avoid paying the telephone fees. Another point of controversy pinpointed by users is a lack of feedback or return in some cases. In January 2017, According to Portal G1 (2017b), over 46,000 complaints were unanswered.

“156 only helps for small requests; if you need mortar picked up, or a drain changed, or something else picked up […] For serious problems, only the cause is looked at, and not the effect.” (Curitiba resident, in an interview for Portal G1, 2014).

“Replies are too evasive and uncertain as to when things will be done […] the service is very inefficient” (Curitiba resident, in an interview for Portal G1, 2014).

“[...] is a system that is well absorbed by the city of Curitiba. It uses and adopts it as its channel, even for small things such as bus itineraries. The city has learned that it may call 156 to know bus itineraries and schedules. But it’s not a good channel for operating the city, because operating cities is a very fast business. The city is constantly flowing, and city operation demands swiftness. If I call 156 because I witnessed a car crash, it will take over a week because of all the protocols and channels this information will go through, even though I’m only requesting support for clearing the lane. I’m not outright dismissing the use of 156, but it might be good for tree trimming. If it doesn’t pose great danger, you might be able to wait a week for the branch to be trimmed.” (Interviewee 03).

According to Interviewee 04, certain factors that undermine citizen’s trust on the services provided by the 156 Central can be outlined:

a) Lower commitment: in 2015 and 2016, faced with the economic crisis, there was an observable decrease in commitment from the sectors responsible for addressing requests made via the 156 Central. This was a strategy adopted by city management when faced with increased demand for public services, as the economic crisis led to increased pressure for free services, as well as reduced budgets;

b) Lower citizen satisfaction: as a result of reducing solutions and lowered commitment by city management for solving the citizens’ demands. When efficient problem solving is observed, credibility is raised and citizens reach out to the phone service more. The opposite is also true: should the capacity for problem solving decrease, the citizen is unlikely to return or request further services using this channel;

c) Fragmentation of institutional relations: in the timespan between 2012 and 2016, there was a decrease in institutional and financial relations between City Hall and ICI, resulting in reduced staff working at the Central. With fewer attendants, there was a decrease in customer service quality and an increase in abandonment rates among users of the hotline (the citizen calls, waits for too long and gives up on the service, and thus fails to communicate the problem).

Table 1 summarizes the main findings observed, linking them to the theoretical premises outlined in the second section of this article.

Table 1 Results relating to theoretical premises

| Results observed | Theoretical premise | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| High number of demands via the Call Center (even though other means of communication, such as social networks, have contributed for a decrease in this figure) | Increased public participation as a way for smart management, with reduced bureaucracy | Toppeta (2010) Galdon-Clavell (2013) Komninos (2007) FGV (2014) Sæbø et al. (2008 |

| Existence of protocols and strategies previously systemized for demand resolution | Interoperability between data and systems for smart city management | Avelar et al. (2006) |

| Increased demands due to uncertainties stemming from transition between terms in municipal government | Data management dependent on arrangements between government and institutions | Barns et al. (2016) |

| Decreased demands due to inefficiency in problem solving and/or lack of feedback | Trust and cooperation as fundamental factors for the creation of smarter urban spaces | Komninos (2007) |

Source: own elaborations based on 156 open data of Curitiba Municipality.

The issue of trust in the governmental sphere is important in evaluating Curitiba’s service 156. It is considered that in the broad context elements as influences, relationships, visions, interests, alliances, conflicts and limitations could guide the maturation and success of the project. In this sense the service can not be understood without the actors involved in the project, the broad context of the moment of creation, the facts and factors that converge forces and actions that result in the analyzed case.

In summary, after analyzing the data, it is identified as fundamental steps to build trust in the citizen-management relationship:

a) The history of urban planning in Curitiba, reinforced with the projects in the 1960s;

b) The continuity of the most comprehensive urban projects, even with the change of management over the years;

c) The creation of internal and external organs to the City, as a form of support and strategy of agility in the delegation of tasks;

d) Feedback as a devolution and closure of the process, seeking the citizen’s well-being as a priority throughout the attempt to solve the problem.

Conclusion

This research made it possible to observe that the case of 156 Curitiba served as an inspiration for other Brazilian cities, which implanted the same model totally or partially. The 156 Central is a consolidated tool for approximating citizens to City Hall in Curitiba. The high incidence of demands made through this channel emphasizes the service’s appropriation by the city’s residents. The data collected, as well as the interviews carried out seem to show several factors are able to influence the number and effectiveness of services provided. Among those, external factors are of the utmost relevance, especially those related to economic resources, as well as internal factors, mainly when linked to integration between urban sectors and political/institutional arrangements.

Although there has been a possible weakening of the service due to various management changes, the supply of the tool as a whole has been maintained. This reflects in a technical-institutional maturity, as well as in a population empowerment in the use and increase of confidence in the system as the population began to observe the resolution of the mentioned problems. This fact evidences that the public power see this technological tool as an ally beyond the purely political unfolding; also for the well-being of the population in a more continuous and safe way. In addition, although data shows that feedback of demands does not occur in 100% of cases, most returns improve the service as a whole. It shows respect in the government-citizen relationship.

This systemizing leads one to conclude Curitiba’s 156 Central is a service that improves city smartness, as it is a consolidated initiative thoroughly appropriated by the population, as well as a pioneering project in the treatment of public demands, still extensively used even as faster and more sophisticated communication alternatives arise. Nevertheless, the service can still be greatly improved, for the factors responsible for its fragility may still be addressed by further developing governmental/ institutional relations in the city.

This researched posited as its goal the analysis of the management/ citizen communications process in the city of Curitiba, using the concept of smart cities and the idea of increased trust, based on the experience of the 156 Central. An empirical analysis of the management/citizen communications process in Curitiba was carried out based on that initiative, considering factors that influence the demand for information, such as de-integration of public services, formal education levels, geographic location and political and institutional arrangements. Moreover, the research attempted to discuss the factors that may contribute for the continued use of this analogic tool, even faced with the rise of ever more advanced ICTs, such as social media and online chat tools.

It was observed that the 156 Central has a solid relationship with the citizen of Curitiba, even though it is a service considered analogic, in which citizens actively call the hotline to describe their demand and an attendant (qualified human capital) receives that information, qualifying it and categorizing it. The entire process is carried out by people, with relatively little support from technology. Granted, the technological advancements made over the last years has allowed for greater inclusion of faster and more sophisticated communication tools, the strategy employed in this service has not undergone drastic or relevant changes.

As the 156 Central improved its processes and its capacity of handling the city’s demands, the service underwent expressive growth. As for matters of credibility, when city management decides to reduce its capacity for action and response to citizens’ demands, residents tend to lose trust in the service, which results in falling demand and an overall lower trustworthiness of the system. This means the system’s efficacy and transparency is directly tied to trust established by the service provided. Moreover, factors such as interoperability and integration between data and systems, as well as arrangements between the political power and institutions, are fundamental for increasing trust in and overall effectiveness of the services provided by the 156 Central.

This research is focused on characterizing management/citizen communications in Curitiba through a specific tool and at a specific moment in time, which in turn does not allow for generalizations or inferring more about the global scenario regarding these relations. Future studies may be developed aiming to compare the 156 tool to other means of communication in Curitiba, such as social networks and specific mobile apps. Furthermore, comparisons may be established between the Curitiba Central and other similar initiatives implemented in other cities.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)