Introduction

The ecological crisis observed today is, in essence, social and cultural, influenced by a cognitive, emotional, and experiential crisis stemming from the inability of modern society to conceptualize flora and fauna as global citizens. Although even their vital processes are not considered important, it is necessary to achieve a fair and democratic coexistence with them. In this sense, if the crisis in question is built around cognitive, emotional, and experiential crises, the solution could lie in the design of a new social contract through education. Due to this, it is vital to encourage the creation of informal spaces within formal education using strategies that allow a pedagogical interrelation of individuals and society, as well as society and ecosystems.

One characteristic of modern society is to relate to nature through the media, where the complex reality of nature is presented optimistically, in order to prevent society from ‘reading’ the socio-ecological crisis it is experiencing. Learning to ‘read’ reality can be facilitated through the creation of alternative in situ educational spaces. However, this must be an integral effort in which human beings seek out spaces for cognitive, emotional, and experiential reconstruction. All this focuses on the creation of pedagogical activities that encourage a recreational reunion with nature. For the purposes of this work, this type of education is called ‘in situ education’, as a framework for socio-ecological literacy.

In this context, both literacy teaching (seen as a permanent reflective learning process) and resilience (seen as a characteristic process among certain people to learn from adversity) are essential to develop a holistic strategy. The evolution of such a strategy would permit individuals to interact responsibly and harmoniously with the ecosystems and societies when they are tourists, for example. This would additionally serve as a setting to support local actors to rebuild their life’s ambitions in their territory. Based on this context, the following work describes how resilience and literacy teaching can serve as ways of building other ‘readings’ of reality. In addition to the above, the article proposes a socio-ecological literacy model based on the review of resilient territories that have managed to permeate people’s thinking towards a substantive ecological awareness based on the approach to these experiences. Furthermore, it shows a way in which management is applied, in a prospective and participatory manner, to build ethical and responsible tactics for a more sustainable behavior.

1. Resilience as a strategy for social growth

Health problems found in rural communities are often related to pollution and a lack of available medical services that worsens due to the absence of financial means to maintain minimum welfare measures. A possible cause that is worth to be cited is:

the accelerated expansion of the modern segment of rural society is, consequently, causing greater and more severe environmental problems observed in recent decades. Workers are poisoned in the fields, while their families suffer from the effects of chemical and organic contamination in their communities (Barkin, 1998: 7).

These problems, caused by pollution and lack of material wealth, make rural society extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Rural people are always facing structural challenges. Those challenges are difficult to overcome due to their economic, social, and environmental conditions. There are always stranded passengers kept from getting the first step on the road to development. A strategy to reduce poverty and the environmental crisis could be possible through acts of solidarity between strangers willing to recognise that alliances enable the creation of better solutions to collective problems.

Those who are part of modern society have little idea of the impact their lifestyles (based on the excessive consumption of luxury products) have in rural families. In this same line, (Dodman et al., 2009: 152) point out that:

the countries that have profited from high levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are the ones that will be least affected by climate change, while countries that have made only minimal contributions to the problem will be among the most affected.

However, all countries will be affected to a lesser or greater extent, even with the conditions of inequality that their effects imply.

It should also be said that a civilizing model, which is aggressive towards different types of species (including humans)- inhabitants of rural areas are disproportionately affected by climate change. A series of questions can be asked in this regard, for example, to what extent could proposals be implemented in order to catalyze alliances based on solidarity and democracy? Furthermore, is it possible to recognize needs in traditional societies without assuming missionaries’ views? Finally, is it possible that this process stops the generation of missionary approaches and begins to portray images of the social and ecological power of local people in a specific location?

Answering these questions necessarily entails a holistic process. Because of this, the resolution or mitigation of the effects of global climate change depends on the active participation of the inhabitants of a given location. Regardless, this participation should not feature charity as its cornerstone, but rather as a contextualized accompaniment as a political movement that helps people to help themselves (Ellerman, 2005). This requires processes that see potential and strengths within communities instead of seeing only limitations and hopelessness. For instance, local wisdom. Farhan and Anwar (2016: 173) say, when referring to local wisdom: “It can be defined as local cultural wealth, which contains the policies of life; view of life (way of life) that accommodate policy (wisdom) and the wisdom of life”. On the other hand, these skills -sought out by this research- are forged through the learning processes spurred by historical adversity and are found on both personal and community levels. Kotliarenco et al. (1996: 2) say:

the manner in which one understands [reality] largely determines the actions taken with regard to socio-ecological problems. [For example] if we understand reality to be a grouping of deficiencies, lack of funds, lack of goods and lack of services, any action on our part will be directed towards “mitigation”, “assistance”, or “subsidization”. [However], if we consider it to be a futile human experience that uniformly affects those who live it, characterized by a series of ‘negative’ factors -deficiencies and [environmental] problems- with the potential to allow for survival in poverty conditions, strategies to allow for overcoming [socio-ecological] problems will be directed towards providing opportunities.

This process is called resilience. It is important to recognize that resilience is a relatively new concept that has nevertheless been addressed by social theorists (Table 1).

Table 1 Resilience implications

| Theorists | Resilience implications |

| Fraser et al., (1999) cited in (Villalva-Quesada, 2003) |

|

| Masten (1994) |

|

| Luthar et al., (2000: 53) | “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity”. |

| Rodin (2014) | taking as examples big crises around the world, it emphasizes the importance of social cohesion when facing adversities caused by urbanization, climate change, and globalization. |

| Sherrieb et al., (2010: 228) | “resilience is related to those adaptive capacities of a society that defines its emergency preparedness”. |

| Kapucu et al., (2013) | there are four elements for resilience:

|

| Grotberg (1996), Puig-Esteve and RubioRaval (2011) | do not consider resilience to be a fixed or innate ability, but rather something that can vary depending on time and circumstances. Due to this, resilience is a process that is present throughout individuals’ lives, and that can be enhanced through the implementation of appropriate techniques. |

Based on the above discussion, it can be said that resilience is more a temporary state than a way of being, in which humans can discover their ability to resist and recover when dealing with an adverse experience. When facing the challenge of confronting situations with an attitude that brings about intense internal dialogues, our imagination prevails. These dialogues then prompt stability and well-being. As such, it is important to stress the dynamic nature of the concept. Resilience, then, is a process that deals with dynamic adaptations to risky situations that threaten individuals or groups, such as the lack of means to consume and produce, in order to build a decent life. It also has to do with the capacities that someone or a group of people has built over time that makes them to be prepared for an unexpected catastrophic event. In this sense:

even though [resilience] requires an individual response, it is not strictly an individual characteristic since it is conditioned by individual and environmental factors. These factors are the products of vast ecological heterogeneity influences, which unite as a response to an important threat (Villalva-Quesada 2003: 3).

Emily Werner (1997) carried out a study supporting the above propositions. She analyzed a multi-racial group of children from Kauai, all of whom had been exposed to psychosocial stress for 40 years. Werner succeeded in identifying various protective factors inherent in children, including self-esteem, introspection, independence, ability to relate to others, initiative, morality, humor, and critical thinking. Werner called these factors ‘pillars of resilience.’ Wolin and Wolin (1993) called these factors ‘protective characteristics,’ but they are also sometimes called ‘shield characteristics.’ In the present work, the variables laid out by Werner (1997) and defined by Wolin and Wolin (1993) are analyzed while separated within the collective. That is to say, the search will lean more toward social than individual areas. In that, resilient societies are thought to generate strategies to address their needs, there are often alliances formed within them (among individuals, families, and societies) whose objective is the incorporation of varied abilities that can then be used to fight vulnerability and poverty.

1.1. Resilience in a territory

Humanity has struggled for centuries to dominate Nature, which is found in the different territories where its residences are located. In this journey, humanity found reasons to stop twinning with other species, calling itself “human being” and in doing so, it tagged the other species as inferior. Thus, when labeling them, humanity was in the position of giving them an instrumental value that allowed it to take them, transform them, market them, and discard them as obsolete objects; transforming the territory in unsustainable ways.

Jorge Riechmann (2014) asserts that we may be at a point of no return in ecological-social terms, he also summarizes unsustainable forms in three major themes that are present in everyone’s sight and give a special characteristic to our times: “The global ecological crisis [...], the planetary social inequality increasing -and historically unprecedented- [...] and, finally, the challenges posed by the technoscience that emerged in the 20th century” (Riechmann, 2014: 17). “These three aspects are the challenges that urban and rural societies have to learn to deal within their ways of seeing the world. But, undoubtedly, it would be necessary to stop generating strategies that create sustainable territories that dispose their waste to other pieces of land with less possibilities of carrying out political, economic, social, or cultural activities. That is, less resilient. Creating spaces of well-being, where a few manage to realize all their desires, causing the “others” to witness, with their arms crossed, how their life project is dismantled; while their territory becomes vulnerable to their astonished gaze. Humanity, as a whole, requires understanding that the species can survive only if it internalizes that the Planet does not have the capacity to satisfy the desires of all in unison, because it does not have enough natural assets to please each individual. The uncontrollable demands have caused that Nature cannot recreate in its own times, making its resilience capacity more and more diminished. In this sense, due to the industrialized extractions of natural goods, ecosystems do not have the capacity to renew themselves. In other words, “the ability of the species that are part of [the ecosystems] to return to the original state after a change due to natural disturbances or human activities is depleted” (Cuevas-Reyes, 2010: 2).

A resilient territory, therefore, is that geographical space where the species that inhabit it can reproduce and return to have a dignified life after adverse events hit their habitat. The capacity or non-resilience capacity of a territory is not only linked to the number and intensity of adverse events of a natural nature, but also to the capacity and intensity of extraction of industrial societies.

Industrial societies, unlike peasant societies [...], are no longer directly dependent on the natural resources of their immediate surroundings. [However], when determining the ecological impact of the different modes [of production], one is surprised to find two paradoxes [...]. [The first] […] from the spatial point of view [...] farmers live in areas adjacent to the forest but at a remarkable distance, and [the second] urban industrial men live outside the forest [...] the greater the spatial separation of the forest, the greater the impact of its ecology, and the more distant the actors are from the consequences of this impact (Gadgil and Guha, 2002 [2000]: 51-52).

The foregoing would mean that a territory can be resilient only if the societies that live in areas adjacent to the forest or ecosystems have a solidary and reciprocal relationship with Nature. These societies, although they are not immersed in it, they recognize that ecosystems provide them with goods that cover their needs such as energy, when using branches and dry trees as firewood; food, through rational hunting; recreation, by means of its landscapes; a propitious space for teaching young people, on the vitality that Nature is for the collective; and also, a source of medicines being available at all times.

It can be seen that the resilience of the territory is linked to the resilience of the societies that inhabit it; implying that it would be based on having a good life. That is, resilience is communal, collective, forming a solidarity network. It is proper that protective elements arise in these solidarity networks, which emerge as a result of acts of solidarity, organization, and reciprocity. However, networks are not only subject to internal elements, but are linked to external elements that, also in an empathic way, express solidarity through different interventions, either as tourists or sharing their scientific knowledge, so that communities can recover, invent, discard, or reinvent strategies that allow them to reconstruct their life project in an appropriate manner to the ecosystems’ times of recreation.

2. Literacy at the territory

One of the defining characteristics of the current era is the flow of information between different social media. Nonetheless, this information is often not part of a correct reading of reality but rather part of a policy of social indoctrination with the objective of using manipulation to dominate certain human beings. All of those who use domination, those who could be called magi-politicians, economists, and intellectuals, among others use indoctrination to confuse, terrorize, hide, and maintain ignorance with regard to the true relation between domination and exploitation. The opposite process is the liberation experienced through education. However, this must be a process that goes beyond training people to live within a system in which they expend, both intellectual and physical human energy. That is, an education that builds up thought through reflections echoing the world (Freire and Macedo, 1989 [1987]); this can only be accomplished through reflexive, not instrumental, literacy.

Literacy is just that, instruction or support to help someone learn to read. This does not necessarily clarify the direction that this paper is seeking to represent. However, there are other ways to approach literacy teaching. For example, the STS (Science, Technology and Society) movement relates literacy to societal literacy with regard to the impacts that science and technology have on people’s lives. In this sense, the type of literacy conceptualized here goes beyond techno-scientific education to techno-scientific literacy teaching. Martín and Osorio (2003: 169) said regarding this matter that it is “oriented toward favoring a citizen, who is capable of understanding and participating in a world in which technology and science are more present every day.” This understanding of literacy teaching also has the objective of helping society to actively participate in defining the public policies that affect it, instead of observing how the quality of life deteriorates due to unhealthy science and technology. Sanford et al., (2014) offer an alternative perspective for the development of newer conceptions of literacy, taking into account sociocultural, ideological, technological, and spatial influences. Freire and Macedo (1989 [1987]) describe literacy instruction as a process through which human beings learn to think and to discern. Literacy is a process by which a human being becomes aware of what is happening around. This, in turn, liberates them, so that they may assume a position as a participant in history. This process of liberation implies for a person, the adequate positioning in a specific moment and in a social reality with respect to the rest of the world.

Upon arrival at a location, for example, individuals as tourists or visitors face a different social reality, which becomes their reality at that moment. That reality, which is constructed through encounters and relations with the place itself and unfamiliar ecosystems, is not only present in the world being visited, but in the world considered to be a tourist destination. Although the tourist is separated from the panorama of the destination, they become part of said panorama upon learning to read the complexity of the reality present there. Freire and Macedo (1989 [1987]: 32) reflect on this point, saying: “as there are no men without a world, without a reality, the movement has its roots in the relations between man and world. From there, the starting point lies with men and their here and now which constitutes the situation in which they find themselves immersed”.

In addition, this new approach to literacy teaching goes beyond academic contexts by recognizing that different social actors can give literacy instruction to society more effectively from the holistic perspective of wanting to learn to read reality while also learning to be with the world instead of being alone in the world. From this perspective, literacy teaching is seen as characterizing the connections between informative content and the broad goals of humanity, as well as between styles and types of life. By seeing these characterized through literacy teaching, one can note the social and ecological diversity that gives a political backdrop to these realities. It is interesting to note that international organizations have tried to adjust the concept in order to create a more integral and pluralistic vision. UNESCO (2004: 6) sums it up in this manner:

the conception of literacy has moved beyond its simple notion as the set of technical skills of reading, writing and calculating […] to a plural notion encompassing the manifold meanings and dimensions […] [this vision] recognizes that there are many practices of literacy embedded in different cultural processes, personal circumstances and collective structures.

Based on the above discussion, it can be said that literacy teaching is no longer built upon teaching reading, writing, and mathematical operations in order to permit entry into other fields with other knowledge and abilities.

Despite this, this process requires the intervention and convergence of various social actors in the political, social, economic, and cultural life of a given location. This allows a flexible and internalized program that gives literacy education to people when they are tourists or visitors at their destination in a leisurely context. However, the fact that it possesses these characteristics does not make it less critical or responsible, while it should not provoke a feeling of fevered activism or serve as a type of occupational therapy to give the feeling that the tourists or visitors are saving the world. It should cause reflections that call into question one’s position as a comfortable tourist -one who demands many social and ecological necessities, thus affecting the locale.

Finally, a multifaceted process is proposed in which plurality plays a key role by means of the variety of voices that converge in a destination or territory. This is, that different actors (such as social, academic, governmental, financial, host community, media, touristic, etc.) are managed in a working and participative team in order to build a specific strategy aiming to provoke such literacy through reflexive leisure.

3. Individuals’ responsibility in the host country territory when they are tourists

Firstly, it is important to make a difference between territory and destination. The first has to do with the place where people invent, build, discard, rescue, and internalize their own and others’ things to maintain their life projects. On the other hand, destination, from the tourists’ point of view, is that dream place that promises the traveler great experiences, without having to look at the disadvantages of the inhabitants around them. Regularly, the destiny is a socio-ecological bubble, where the ways of life of those who have the possibility of traveling and getting to know the world are reproduced in a standardized manner. However, there are travelers or tourists who are willing to know the territory in a responsible manner.

Ooi and Laing (2010: 191-193) bring up an interesting point regarding tourists’ behavior towards responsibility at their destination. They propose that there is a growing number of tourists seeking out ways to travel that provide alternatives to ‘normal’ tourism. The authors discuss two important examples of this phenomenon: backpacking tourism and volunteer tourism. While the first of these types of trips is based on the tendency to consume few resources in order to avoid spending money as much as possible, the second involves tourists paying to participate in organized projects based on specific interests. These are often focused on supporting cultural and natural spaces in the local area. The authors cite Wearing (2001: 1) who defines volunteer tourists as:

those individuals who, for various reasons, volunteer in an organized way to undertake holidays that might involve aiding or alleviating the material poverty of some group of society, the restoration of certain environments or research into aspects of society or environment.

This sort of tourism is not only based on a desire to help a community or locale, but it is also influenced by participants’ egos. This aspect of volunteer tourism, connected to the altruism that characterizes it, is what Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (2002), cited by Ooi and Laing, 2010: 195) have labeled ‘Individualized Altruism,’ to which the authors have suggested adding a social component such as working with people in the location and getting to know people in order to experience local culture. This goes hand in hand with the WTO’s (n. d.) proposal to travelers and tourists regarding responsible activities.

On the other hand, Dolnicar (2010) in her work Identifying Tourists with Smaller Footprints says that individuals who exhibit pro-environment behaviors in their homes are also very likely to do so while on vacation. Kals-Schumacher and Montada (1999), cited by Dolnicar (2010: 720), introduce a new construct, which they call ‘emotional affinity towards nature and society.’ This concept can be distinguished from cognitive processes because these findings are in line with other studies that investigated the relationship between a sense of moral obligation and an eco-friendly behavior. Another finding reported by Dolnicar (2010) was that people with eco-friendly behavior had a higher level of education and, as such, had enough money to volunteer while on vacation.

Dolnicar (2010) presents an exhaustive literature review regarding eco-friendly attitudes in which she cites Berenguer et al. (2005), who put forth the idea that there exist both socio-demographic and psychological determinants for expressing concern for the environment. The first of these determinants has to do with age, ethnic group, place of residence, earnings, gender, religion, and ideology; while the second is related to social values towards the environment, altruism, and egotistical motivations. Berenguer et al. (2005) is strongly related to the idea that moral obligation has a strong association with eco-friendly behavior. Dolnicar (2010) also references the work of Carrus et al., (2005), who identified the regional identity variable. If it is indeed true that this variable cannot be present in tourists, then it can be inferred that people who are accustomed to living in solidarity with their ecosystems will exhibit the same solidarity when they are tourists. All this is closely related to childhood experiences. In this sense, Kals-Schumacher and Montada (1999) cited by Müller et al., (2009: 59) suggest that:

affinity toward nature can best be described as an emotion that develops through experiences with nature during childhood. Their construct is constituted from four aspects of this emotion: love of nature, feelings of freedom in nature, feelings of security in nature, and feelings of oneness with nature.

On the other hand, Dodds et al., (2010) in their work “Does the tourist care?” give an interesting example of the contrast in behavior between individual tourists. They make a comparison of tourists in Koh Phi Phi, Thailand and Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. The authors found that tourists had differing attitudes based on where they were visiting. So, while 95% of tourists in Gili Trawangan were willing to pay an extra fee to protect and care for the environment, only 75% of tourists in Koh Phi Phi were willing to do the same. Because of this, the present investigation will have to carefully define the indicators used to determine whether a tourist is responsible or eco-friendly.

If it is true that there are individuals who -because of their education and earnings level- have the ability to participate in responsible tourism, there are also a great number of them who have neither the education nor the money to be a social or ecological volunteer while on vacation. In this sense, it is not only desirable to only attract eco-friendly tourists and the experience can serve as a pedagogical exercise for everyone regardless of their socio-economic class. The environmental crisis should be a factor that drives home the importance of giving literacy instruction about social and environmental topics. This way, humankind can come to understand that it has a moral obligation with respect to ecosystems and society, thus its actions come to be seen within a pro-environmental context regardless of location or situation.

3.1. Strengthening territorial resilience

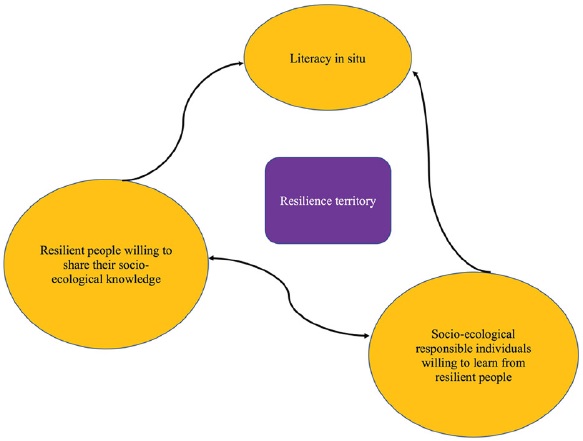

The union of responsible tourists and local actors who are also responsible may well give an important turn to places seriously impacted by the environmental and social crisis. Locals could rebuild their life project, making their territories become ecologically resilient spaces, this is represented in Figure 1.

On the other hand, tourists who did not have the opportunity to live a childhood close to nature would know the importance of solidarity with those projects that work to build naturally recovered spaces. The socio-ecological literacy of people, when they are in their nature of tourists, offers the opportunity to create ‘ecological moles’ that would serve as a refuge for species and people eager to rediscover or find themselves in a vivid way with the images offered by Natural Geographic or Animal Planet; while it catalyzes processes of reconstruction of life projects of people harmed by capitalist extractivism. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that resilience is not a panacea for solving problems magically. Resilience is “the human capacity to overcome traumas and wounds” (Barundy, 2016: 1). In this area, rural and peasant communities have a lot to say about how to survive in impacted territories and how -when they have social solidarity- they manage to recover them. An example of that process is found in an organization called Tosepan Titataniske. This organization has brought, for 41 years, well-being to its members, through projects that have the objective of accompanying them to the recovery and reconstruction of life projects. This is an example of territorial resilience because they have intervened in it, as a group of actors that manage to ally to face ecological and social adversity in which the territory is immersed, where they, in turn, recreate their ways of seeing the world. It is important to mention that the construction of this territorial resilience has been possible thanks to the solidarity among social actors. The Tosepan Titataniske Cooperative is an example of how they alphabetize their visitors or tourists by showing how they have organized themselves. Among the teachings that can be observed are:

[the impulse of] food sovereignty through social/environmental awareness, local development with short circuits for consumption. Guaranteeing self-consumption with the generation of local employment from a greater productive diversity, the creation of solidarity and training networks continues in favor of improving the quality of life of the local population and a progressive local expansion. The elements towards the promotion of biodiversity stand out, as well as the optimization of recycling rates for organic materials, such as an efficient use of energy and resources; advances in the strengthening of local cooperation and identification of solidarity mechanisms; self-management through participatory training and education processes. Handling all this with rootedness and respect for cultural traditions, cultural and ethnic plurality, endogenous development, plus local knowledge in the management of natural resources. The Tosepan Titataniske is governed by harmony and balance between economic systems and natural resources with a high degree of autonomy and local management (Gutiérrez, 2011: 1).

This example, which Víctor Manuel Toledo has called “The Cuetzalan Model” (Toledo, 2011), has as an important achievement: an ecological ordering of its territory with the support of the Benemerita Autonomous University of Puebla (BUAP), thus achieving the social control of their territorial resources. People who visit Tosepan have the interest in learning how to live away from products that harm health and family finances. Creating spaces within the context of territorial resilience would give society a vast number of possibilities to learn, through extra-mural litercy, how to deal with the environmental problems that are no longer fiction stories.

Alejandra Toscana-Aparicio (2011) in her article “Actores sociales en la gestión del territorio y riesgos ambientales en la Sierra Norte de Puebla” explains how the Cooperativa Tosepan Titataniske is very clear about the meaning of resilience, we can say that this knowledge is based in self-care (Foucault, 2011). The author tells how La Tosepan has undertaken different actions to make the territory resilient, among them, one of the most relevant is the issue of natural disasters caused by hurricanes that hit the region. The organization has managed to learn from them. In this sense, La Tosepan established, in response to adversity, to monitor storms through direct communication with the National Meteorological Service, bypassing the Civil Protection System. When the storms arrive in the region, La Tosepan builds shelters that are supervised by their partners without using the state ones, since these sometimes do not provide the adequate service for the people who come to shelter, endangering their lives.

It is important to emphasize that one of the characteristics of resilient people is their ability to share their learning in solidarity with others. The Tosepan not only allows its members to protect themselves from danger in the shelters, but it also invites all the inhabitants to also take refuge in them. This type of attitude is what makes the territories become socio-ecologically resilient spaces and favorable for the literacy of the rest of society. However, the territories are not only threatened by global warming but also by the interests of large companies, which attempt to gain control of the natural resources that are there. The video “Academy on Social and Solidarity Economy” (Tosepan Titataniske, 2015) describes who they are and their relationship with Mother Earth.

Another exemplification of the construction of a resilient territory is the Cooperativa Las Cañadas located in Huatusco, Veracruz. It is a place visited by tourists who want to learn how to best interact with ecosystems. The cooperative offers courses according to the times of recreation of nature, that is to say, according to seasons. For example, February is dedicated to agroecological issues and biointensive cultivation; May is devoted to honey production by native bees; among other courses published on its page. Las Cañadas, unlike Tosepan Titataniske, is a Cooperative created from the dream of Ricardo Romero, who inherited 300 hectares that contain a mountain where the cloud forest ecosystem is recreated. The intention was to continue with the family business, raising cows. It is not surprising that the territory was severely impacted and the mountain had no trace of its native ecosystem. Nevertheless, he chose to convert it into something that could remain in time and that, in addition, contributed to a sustained manner to the mitigation of the environmental crisis. During the change process for sustainability, it was recognized that the reconstruction of the territory was not an individual effort but required the participation of other people. So, as a first step, it was decided to invite farmers to experiment new approaches to farming in these lands, so that later they would take this experience to their own lands. Yet, before achieving the cooperative constitution, they experimented with several projects that had a sustainable dye, but they were not able to be properly defined. This is a clear sign that social resilience is built along with ecological resilience. It is important to emphasize that local people participated in all the trials towards sustainability. Eventually, in 2006, Las Cañadas was established as Cooperative, where Ricardo Romero joins as a worker and does not take a position of owner, becoming part of the community, as can be seen in the legend of “Our shared dream”. See Photo 1.

We are a community united as a family that works and lives sustainably. Being organized as a cooperative allows us to work with commitment and responsibility. Simultaneously, it enables us to take care and use to good effect, our natural resources in order to achieve a cheerful and simple life, with equal opportunities and without shortages. Motivating this, an education that entails our children to follow their dream, which is ours too; as well as exchanging experiences, services and products with others (See Photo 1).

The last sentence “exchanging experiences, services and products with others” defines the availability of sharing the knowledge acquired over the years. In this sense, Las Cañadas constantly receives groups of people who decide to stay and learn about sustainable living, materializing resilience and literacy in a single space. Therefore, they are ideal spaces to cover the need to train urban societies on how to survive social and environmental risks. This allows to say that resilient territories are propitious for a socio-ecological literacy on how to stay safe; but more specifically, how to adapt to the complexity and uncertainty existing on the Planet.

It is important to mention that different external actors, such as visitors and tourists, have supported in solidarity both Tosepan Titataniske and Las Cañadas, since they are interested in learning to live more sustainably. The exchange makes it possible for the land to strengthen and become, little by little, a resilient territory, as happened with Las Cañadas, which went from being a mere livestock land to a territory where people permanently seek to have a “sustainable life”.

The emergence of tourists and territories, such as those mentioned above drives us to think that it is possible to change the paradigm; but it is necessary and urgent to create these spaces of territorial resilience to form a platform where alliances are interwoven for the regeneration of the broken ties between human species and Nature.

A socioecological literacy model is proposed, taking up practices and experiences based on these two cases of resilient territories.

4. Socioecological literacy model

The model here outlined drawing from two resilient territories, Tosepan Titataniske and Las Cañadas, which although they have variations, they coincide in different aspects. In terms of natural conditions, both have a vast nature, one located in the central area of Veracruz and the other in the Northeast Sierra of Puebla. Also, a fundamental fact in both is the fact of being organizations with priority in the collective. Even though the first is born as a cooperative, and the other is formed into a cooperative by considering elements of equality and equity of those who are part, which demarcates a process of uprooting individualism by the collective. Table 2 shows in detail the characteristics of Las Cañadas and Tosepan Titataniske.

Table 2 Characteristics of resilient territories

| Las Cañadas | Tosepan titataniske | |

| Conceptualization of space | Center for agroecology and permaculture, where one of the last fragments of cloud forest is found in the central zone of Veracruz. | Cooperative organization of small owners that emerges in the Northeast Sierra of Puebla; in a territory that has a vast nature. |

| Size | Cooperative society with less than 30 members. | Regional Cooperative Society in constant growth. |

| Characteristics of the organization | All partners have responsibilities, rights, and obligations to fulfill so that the project achieves its goals (social, economic, and ecological) and that the benefits are fair and equitable. | Conformed by inhabitants of the Northeast Sierra of Puebla, mostly indigenous people of Nahuatl and Totonac, organized to work with the purpose of improving the living conditions of their families, their communities, and their region. |

| Path |

|

|

| Main value | Harmonious relationship between society and nature | Harmonious relationship between society and nature |

Source: self made.

4.1. Actors

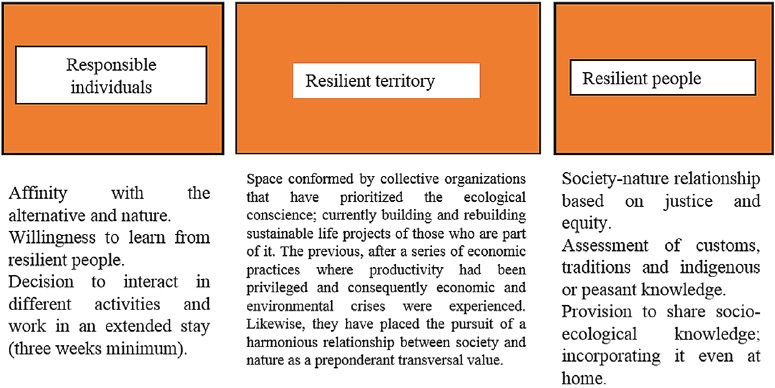

Socioecological literacy is a process in which two actors and a territory converge (Figure 2). The actors, resilient people and responsible individuals, both have in common an affinity for nature, although each in a different way. That is to say, the first, as part of the resilient territory, has transited in its way of living and thinking from experiences; while the second has looked at the environmental conditions and recognized the need for changes that favor the ecological. Although it is not possible to point out the moment in which each of the actors became or will become an ecological subject as “it does not emerge [...] enlightened by an emancipatory consciousness of the environmental crisis. [Since] these elements are emancipating from their condition as subjects through a deconstruction of the rationality that has shaped them” (Leff, 2010: 2). What is observable is that this will not happen immediately but in the medium term.

As for the territory, considered as a space (Santos, 1985) in a totality that includes men, companies, institutions, the so-called ecological means, and infrastructures, which have undergone a process of changes that range from a series of economic practices where productivity had been privileged and as a consequence the suffering of economic and environmental crises; for what to become a resilient space implied a history with disagreements and successes, that finally arrived at a place that privileges the harmonic relation of society-nature.

4.2. Process

Although the beginning of the process of socioecological literacy arises from the arrival of responsible individuals, before its arrival, visitors already have an affinity for nature, recognizing the critical environmental and social condition that the world is experiencing. Notwithstanding the beginning of the process, in this approach, it is considered as of its arrival. Once established in the receiving place, it is considered necessary a talk or workshop where history, project, and philosophy are outlined around the nature-society relationship. Here it is necessary to point out that socioecological literacy does not concentrate on this first activity, no matter how deep the conversation -or on a general path through the work of the organization and nature. In any case, these activities only make up an edge in the literacy process.

In the case of the Tosepan organization, tourists are shown, by means of a one-to-two-hour tour, the generalities of the organization and the ecotecnias, mainly. However, who actually leads the socioecological literacy is who gets involved in diligences of the organization, being then when the alternative thinking of the organization and the philosophy with which they relate to nature is achieved to perceive it with great clarity. For example, those researchers who come to Tosepan Titataniske with the intention of doing field studies, as acts of mutuality, are assigned a job, usually teaching, as an act of reciprocity with the association; being precisely those moments in which better learning is carried out. If the above is added, the creation of bonds of trust with some families that are part of the organization, even making informal visits in their homes, the memory collected is greater.

As for Las Cañadas, there is a defined program that covers three weeks as a minimum of permanence. In such a way that the responsible individuals are involved in different activities, from assigning tasks as part of the community to informal tours and talks, which allows them to receive a profound learning of simplicity of life that harmonizes with nature.

It is a fact that who receives an environmental sociological literacy is not the same again; the individual will have traveled to be an ecologically aware being and willing to impact its immediate environment from its experience.

What is relevant, within this, would be that education ceases to be a transmission belt of hegemonic values and instead focuses on showing how to mitigate or prevent the risks in which the human species is immersed. The industrialized society cannot see the seriousness of the situation. That is to say, the further away the society is from “natural” ecosystems and the more it is submerged in cement ecosystems, the ecological impact is greater; but the recognition of those impacts is almost impossible since Nature is already processed and packed (Gadgil and Guha, 2002 [2000]).

Conclusions

A reality that the human species must take into account is that it inhabits a Planet that does not have the unlimited extension of resources that had been considered until a few years ago; but, as a society, it must be realized that everyone’s wishes or interests cannot be fulfilled at the same time. In this document, a proposal is made to alphabetize society outside the walls of educational institutions, specifically when their mental state as tourists or travelers allows them to be open-minded to different experiences. At the same time, it is important to catalyze the creation of resilient territories, specifically those territories where society has a close relationship with Nature. Both literacy and resilience are considered central axes; since together, they become a catalyst to provoke the required cultural change. It is urgent that urban society learns to relate in solidarity with individuals belonging to other species. There is also an urgent need that society itself do so with individuals of the same species. The strengthening of rural communities through a solidarity construction of resilient territories offers hope to stop the race in which society is immersed. People must be aware that there are alternatives and, above all, know that these alternatives are found in the rural world; but it is necessary to accompany them to reconstruct their life projects so that these communities, in turn, are able to share other ways of seeing the world, that is, by teaching us to be literate.

The literacy received in school does little to evolve from instrumental to reflective, this only has to do with joining letters, arithmetic issues, and memorization of capitals. In this sense, a large part of modern society consumes information without digesting and comprehending it to interpret the reality that media provides. The political project for education is based on the generation of citizens with instrumental skills; but without the capacity to reflect critically on situations that involve the environmental and social crisis. It is urgent to co-establish the literacy of society and the reduction of poverty of the peasant peoples. In this sense, it is proposed to create resilient territories where local actors can recover their dignity through training incoming tourists to face the unsustainability that overwhelms the Planet. It is important to emphasize, as we can see in this document, that there is an emerging sector of tourists looking for spaces to find a different way of relating to Nature. Resilient territories, such as Tosepan Titataniske and Las Cañadas, are also flourishing as an alternative to life. Their inhabitants are in constant search to achieve a sustainable life that leads to autonomous processes, while continuing to relate to the rest of society. One of the most important aspects is that the devastated territories, through social solidarity, intend not only to become extra-mural literacy spaces to change our way of seeing the world; but also, to offer generous environmental services that the rest of society cannot see or understand.

The human species is at a crucial moment that deserves a cultural change on how to relate to each other; while it internalizes that the Planet is not a bank full of natural resources. This change of thought can only be achieved through education; which should not be confined only in a classroom; instead it is urgent to strongly link education to experience. It is in this sense that reflexive literacy is proposed outside the walls with the aim of strengthening territories in misfortune, so they can become resilient territories where the human species returns little by little to understand that it is not ‘the species’; but rather it is part of biological diversity.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)