Introduction

Post-cold war entrepreneurship research contends that market economy and entrepreneurship are essential forces in sustaining centrally planned, or “command” economies, even as those states have periodically attempted to outlaw such forces. Such logic assumes entrepreneurship is an “exogenous” variable, one “thing” that is introduced into a society from the outside. However, there is growing evidence that flexible opportunity networks function within command economies despite (or perhaps because of) the rigidity of state planning.

Rehn and Taalas (2004) outlined this phenomenon in their review of everyday exchange or mundane entrepreneurship in the Soviet Union. The authors claim that “the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics might be seen as the most entrepreneurial society ever […] [because it] forced all citizens to become micro-entrepreneurs […] in even the most mundane facets of everyday life” (Rehn and Taalas 2004: 237; emphasis in the original).

The case of the blat, or the economy of favors, sustained the former USSR in ways previously unrecognized. Omitting studies of entrepreneurship in command economies may result from the idea in modern economic and political literatures that the entrepreneurial spirit can only survive in market economies. Rehn and Taalas (2004: 236) outline this conceptual dilemma in this way: “[w]e tend to look at successful societies or regions and proclaim these as entrepreneurial on the basis they exhibit results we assume might follow from entrepreneurialism - reductio ad absurdum”. This paper builds on this notion of everyday exchange or mundane entrepreneurship by examining Cuba in the post-Soviet era (roughly 1990-present). In doing so, we provide a socially situated case of entrepreneurship in Cuba and aim to contribute to how everyday or mundane entrepreneurship can be sustained outside the contexts of the market and business as market economies define them. Our reference to Cuba’s “entrepreneurial realignment” derives in part from the Cuban Communist Party’s Sixth Congress held in April 2011, in which they issued a series of guidelines (“lineamientos,” or aligning principles) aimed at adjusting the socialist model to confront the current economic crisis at home and globally. However, we also chronicle a simultaneous and more organic bottom-up economic realignment initiated through everyday economic practices (i.e., mundane entrepreneurship) of Cuba’s cuentapropistas (self-employed workers).

We show that while the nature of entrepreneurship, its challenges and opportunities are unique in Cuba, this entrepreneurship also shares important similarities with the Soviet blat system and that the phenomenon derives as much from the internal contradictions and pressures inherent to command economies as it does from external influence and models. We draw on original survey research from three key periods -1998, 2008, and 2011- that assesses how budding entrepreneurs tackle small business challenges.

Entrepreneurship in Cuba has undergone substantial realignment since the beginning of the post-Soviet era around 1990. Dubbed the ‘Special Period in Times of Peace’ or simply the ‘Special Period’ by Fidel Castro at the time, this era ushered in fresh opportunities for Cuban entrepreneurs, with the decriminalization of the dollar in late 1993, incentives to attract foreign investment through joint ventures, and the legalization of a limited number of private occupations (Cepal, 1997; Pérez-López, 1994; Pérez-López, 2001).

The literature on Cuban entrepreneurship highlights obstacles for these self-employed workers, where the state still looms large over entrepre-neurial activity (Peters and Scarpaci, 1998; Ritter, 1998; Elinson, 1999; Cruz and Villamil, 2000; Trumbull, 2001; Henken, 2002; Scarpaci, 2002; Osborn and Wenger, 2005; Phillips, 2007; Ritter and Henken, 2014). Thus, the movement away from the Soviet influence seemed to simultaneously liberalize and tighten the regulatory environment in which Cuban entrepreneurs operate (Pérez-López, 1995). Even amidst the unprecedented economic reforms enacted under Raúl Castro since 2008, the official government policy continues to aim at the “perfecting of socialism” (Zawadski, 2009) and ‘perfecting businesses’ (perfeccionamiento empresarial) (Morales and Scarpaci, 2012: 29), so far refusing to fully legitimize the role of the private sector, the market mechanism, or small- and medium-sized enterprise in Cuba’s economic realignment.

1. Background literature

1.1. The cuban economy since 1959

By 1958, Cuba had a large private sector, mainly national, although with a strong foreign presence; a significant state sector; and some “benevolent associations” operated in the cooperative sector. The Cuban Revolution’s nationalizations between 1959 and 1961 eliminated most of the private sector and the older cooperative sector, the impact of which is well known (Gordon, 1976). In 1959, nearly 60,000 retail outlets operated in Cuba but it dropped by two-thirds within a decade (Morales and Scarpaci, 2012: 20-23).

The 1968 ‘Revolutionary Offensive’ entailed the complete seizure of Cuba’s smallest remaining private businesses: hot-dog carts, repair shops, vegetable stands, snack shops, and the like. Without legal recourse, these petty trades were driven underground or out of business (Cruz and Villamil, 2000). Replacing the services that these vendors had provided was a tremendous challenge for the Cuban state in the 1970s (Scarpaci et al. 2002), as it was far less responsive to customer needs and terribly inefficient. Ever enterprising, Cuban citizens relied on an expansive black market for many goods and services traditionally provided by small busi-nesses. It is common today in most Cuban households to have at least one adult -often a retired or un-(under-)employed member- who actively scouts the black market in search of cooking oil, bread, and other staples. Like the Soviet blat system, Cubans have long relied on a buddy or crony system facetiously referred to as socio-lismo, playing off the Cuban term for buddy or associate (socio) and socialismo, or socialism (León, 1995; Ritter, 1974).

The vicissitudes of these tepid private-sector policies underscore a perennial weakness of the island’s state-planning system. Economic goals are plan-directed, resistant to change, and ideologically construed. As Pérez-López (1995: 96) notes:

Attaining economic objectives often demands that managers of state enterprises set low production goals, build wasteful inventories to avoid chronic supply problems, rely on personal favors, bribes and kickbacks to make ends meet, ignore cost and environmental restrictions; produce low-quality outputs, and falsify statistical performance reports.

Hernández -Reguant’s recent anthropological work (2009) vividly illustrates that this characterization of the Cuban economy remains valid today: as the state begins to incorporate capitalist strategies, it has created two key concerns. First, economic disparities within the population have risen and are more pronounced than ever. Second, the state takes advantage of these disparities by promoting the sale of Cuban products, and thus earning much-needed hard currency (Scarpaci, 2010). By the late 1990s it became evident that relatively high amounts of market-based wealth and power began to concentrate in the hands of a small group of people, especially in economically expanding sectors such as those catering to tourists (Dilla, 2001).

The term ‘Special Period’ was coined by Fidel Castro in 1990 to refer to the draconian cutbacks caused by the loss of favorable terms of trade when the Soviet-bloc trading group, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA, or Comecon, founded in 1949), dissolved. Before the Special Period, management was reliant on centralization, five-year planning, and regulation focused on punitive measures for violators (Cunha and Campos e Cunha, 2003). The origins of these entrepreneurial shifts lie in the Special Period, to which we turn in the following section.

1.2. Brief history of self-employment in Cuba

Self-employment quickly disappeared in the first decade of the Cuban revolution as the government nationalized the principal means of production. Professions such as locksmiths, beauticians, upholsterers, and other single-worker enterprises characterized much of this work force. As noted earlier, though, the legalization of the dollar in 1993 moved in tandem with liberalizing work laws (Scarpaci, 1995). By 1996, the government reported approximately 150,000 workers (not quite 2 per cent of the labor force in Cuba at the time) as cuentapropistas. By 2007, the figure had shrunk to about 150,000 (Figure 1) but has climbed to just under the half-million mark as of early 2015.

Data sources: Oficina Nacional de Estadística, Havana, República de Cuba.

Figure 1 Self-employed works in Cuba, 1994-2013 (*000a).

The regulatory environment for these workers has long been shifting and convoluted, but it is tethered to the island’s political economy in key ways (Mitnick 1980). Essentially, small businesses were outlawed in Cuba until recently, presumably because a nascent petite bourgeoisie threatened the socialist system. Home restaurants, for instance, could only employ family members and the number of chairs was limited to just 12 (though reforms in 2010 increased the number to 20, and to 50 in 2011). Certain foods such as lobster and beef were long prohibited from sale in these home restaurants (also rescinded in 2010). However, lookouts often alerted the operators of approaching state inspectors, thus allowing time to hide any wrongdoing.

The case of air pump operators is telling. With the collapse of favorable oil deals for sugar (between the USSR and Cuba), bicycle use soared throughout the island, from about 70,000 in 1989 to several hundred thousand a few years later (Scarpaci and Hall, 1995). Operating an air pump compressor to inflate tires soon became a common self-employment trade. Logically, the ability to patch tires is a parallel service in these settings, but during the 1993-2010 period the Cuban government prohibited the same air compressor operator from patching those same tires! Therefore, many households developed the strategy of having one family member secure a license for the air pump with another working as a tire patcher. Similar Cuban-style ‘economies of favor’ or blat are re-peated across the island and among myriad trades and services, creating what might be considered small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) elsewhere.

Operating a small business requires paying monthly licensing fees by the first of the month. Each municipality has a matrix of prices based on whether the self-employed worker charges in pesos or in hard currency (today called CUCs or convertible currency units). In the case of restaurants, if alcohol is served, then a hefty alcohol license is added to the monthly fee. Thus, a home restaurant in Havana’s Plaza municipality catering largely to tourists and charging in hard currency and serving alcohol might be required to pay the equivalent of $800 USD before the doors open at the first of each month (regardless of the operation’s actual earnings). A similar facility, purportedly charging only in Cuban pesos in the same area, would pay only 400 pesos monthly (about $16 USD).

Authorities can permanently withdraw a business license if any self-employed worker fails to pay their monthly fee on time. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that the state will allow reentry into the market. Seasonal work related to peak tourist arrival months is particularly challenging in this regard. Thus, bed-and-breakfast establishments, restaurants, bicycle-taxi operators, and related ancillary services must ‘weather’ the lean low season, and continue to pay licensure fees during the off-season. Such everyday experiences and mundane enterprises have become the daily bread of hundreds-of-thousands of Cubans -especially since the number of licensed cuentapropistas grew from 150,000 in October, 2010 to more than 450,000 in 2014 (ONE, 2013; Cubadebate, 2014; Feinberg, 2013).

1.3. Entrepreneurship: suppliers and customers

Entrepreneurs are well known for their risk-bearing propensity and in-novation. Much of the benchmark literatures (Schumpter 1942; Leibenstein 1968; Drucker 1958; Hofstede 2001; McClelland and Teague 1975) have treated entrepreneurship as an external variable and, a priori, dismiss its existence in centrally planned economies. In contrast, we claim that Cuba is quite entrepreneurial by starting with Schumpeter’s notion of “creative destruction,” in which the entrepreneur is cast as the principal disruptor who delivers change to moribund economies. The notion is admittedly somewhat reductionistic because it assumes that entrepreneurs are super-human, and their heroic make up leads to a modern economy and society.

One of the most frequent complaints of small entrepreneurs on the island today is the absence of a wholesale market (Cruz and Villamil, 2000). Peters and Scarpaci (1998) noted the problem five years into the cuentapropista experience, and as we report below, it is still prevalent today. The absence of wholesale trade markets is an important obstacle to small business development and an important impetus feeding the black market (Espinosa-Chepe and Henken, 2013). As Ritter observed long ago, restricted access to markets in Cuba is a real limitation for cuentapropistas (Ritter, 1998). Word of mouth, viral marketing, or possibly a write-up in a foreign tour guidebook or in-flight magazine can drive foot traffic to a private vendor. Today, with the advent of Internet sites like Trip Advisor, some Cuban entrepreneurs are attempting to overcome these obstacles using social media that is hosted on servers located abroad.

1.4. Barriers to Entrepreneurship-financial

Venture capital for SMEs offers many benefits (Cruz and Villamil, 2000). In Cuba today, it means relying heavily on remittances from family members (and other “silent partners”) overseas. Recent estimates are that between $1.5 and $2 billion reach islanders from the Cuban Diaspora in South Florida, Spain, and other third countries (Morales, 2009). Morales and Scarpaci (2012) document that some $37 billion USD of cash and inkind merchandise have reached the island between 1993 and 2010, providing a major source of capital for Cuba’s mundane entrepreneurship.

In September 2010, the Cuban government announced it would provide small loans to the half a million state workers who are being laid off, and who might then seek employment as a cuentapropista (Digital Granma Internacional, 2010, Vidal and Pérez 2010). Although details remain vague some four years later, such a policy would reverse one where micro-enterprises traditionally did not have access to credit from the Cuban banking system. The official state newspaper and publication of the Cuban Community Party described this policy about-face this way:

“Increasing the opportunities for self-employment is one of the decisions which the country is making in terms of restructuring its economic policy, in order to increase levels of productivity and efficiency. It is also an attempt to offer workers another way of feeling useful in terms of personal effort...” (Digital Granma Internacional, 2010).

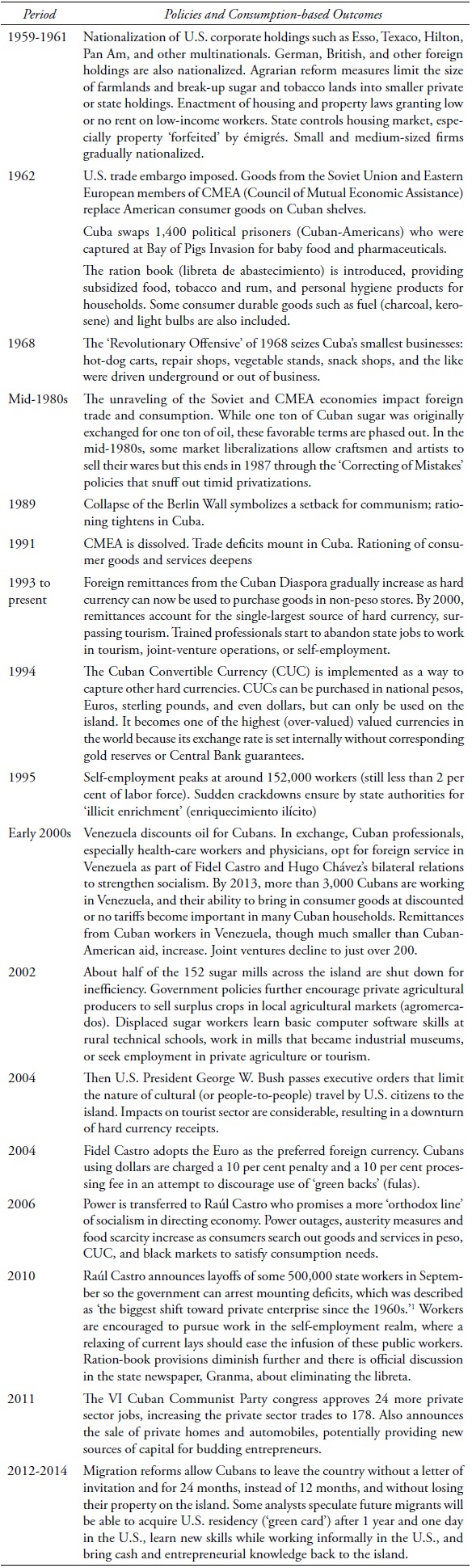

The decided policy shift to market reforms, although lukewarm, marks a long and winding course to the current day (see Table 1). In turn, this may reflect an important cultural change - what the Cuban leadership has called a “change in mentality” (Castro, 2010; Peters, 2010; Peters 2000). Table 1 indicates the incremental and stop-and-go policy changes that characterize entrepreneurship on the island, and culminates with the potentially transcendental moment of President Obama’s December 2014 announcement to lift the trade embargo.

Table 1 Macro-economic Policies and Consumption and in Cuba 1959-2013.

Sources: Compiled by the authors over a number of researches on the field between 2009 and 2014 and based on Cruz and Villamil (2000), González-Corzo and Larson (2007), Morales and Scarpaci (2012), Przeworski (1991), Scarpaci et al. (2002), Pérez-López (1995), and Peters and Scarpaci (1998).

1.5. Political Will

The government’s principal approach to this quandary has been to attack the ‘excesses’ of small enterprise as counterrevolutionary (Cruz and Villamil, 2000) or more recently as a criminal manipulation of the self-employment regulations (Comité Central del Partido Comunista de Cuba, 2013; Frank, 2013; Valdés 2013b). Many Cubans view profit making and wealth accumulation that comes with successful small business enterprise as socially offensive, even if presently necessary (Rosenberg-Weinreb, 2009). However, previous research does indicate that simply ‘being a good neighbor’ and not overtly displaying wealth can alleviate some of these concerns (Peters and Scarpaci, 1998). Straddling the line between prosperity and penury in the changing Cuban economy permea-tes popular culture in Cuba and abroad (Sriram et al., 2007). For example, contemporary Afro-Cuban rap groups such as Orishas, Las Krudas, and Los Aldeanos lace their music with veiled messages about the con-tradictions of a changing socialist system (Fernandes 2003, 2011). Such artistic expressions are simply too ambiguous and common for authorities to easily censure (Block, 2001).

Although Fidel Castro criticized all the reforms implemented since 1993, he viewed them as a necessary evil (Castro, 2002; Ritter, 1998). In 2005, he reflectively characterized the Cuban socialist model this way: “among all the errors we may have committed, the greatest of them all was that we believed that someone really knew something about socialism” (Frank, 2010). In a September 2010 interview with U. S. journalist Jeffrey Goldberg, Fidel Castro candidly revealed the island’s imperfect economic system, when the octogenarian remarked, “the Cuban model doesn’t even work for us anymore” (Goldberg, 2010). Understanding how entrepreneurship has faired over time sheds light on the Cuban model, which is our focus in the following section.

2. Method

We build on Peters and Scarpaci (1998) who found that cuentapropistas were making more than three times the average monthly wage in 1998, paid about 42 per cent of their gross wages for taxes and licenses, and cherished their newfound independence. Having a steady flow of cash allowed them to purchase household goods that suddenly appeared in the state and black markets. When asked about their main challenges as cuentapropistas, the most common response was “no major challenges,” followed by “high taxes and licensing fees.” Surprisingly, illegal shake-downs, bribes, and kickbacks were not reported by any of the 152 informants back in 1998. Rather, the inability to buy wholesale products ranked as their second concern.

Back in 1998, Peters and Scarpaci repeatedly heard stories about the seemingly arbitrary and inexact ways state inspectors determined whether legal (e.g. state-store purchased) inputs into production were used by a cuentapropista. More recently (2014), similar tales continue to unfold. A jeweler’s tale reveals the logic of the inspector: if the proper receipts could not be provided for the batteries, watch bands, or faces of wristwatches, then the jeweler would be accused of purchasing the parts on the black market, which presumably is stocked by stolen items from the state or from illegally imported supplies.

In the worst of cases, the owner could be charged with “illegal enrichment” or theft of state property, both of which carry stiff fines and potential incarceration. Tales like these were echoed by a majority of the 1998 informants (Peters and Scarpaci 1998), as well as in the later two surveys discussed below. The authors heard repeated stories of self -employed workers in Havana changing their prices wildly, or failing to post them. When confronted, they responded to customers that because they were not state workers, they could charge whatever they wanted, and quickly change their service guarantees (watch repairers, upholsterers, and body-shop repair specialists were cited).

The method here replicates the study of Peters and Scarpaci (1998), with the aim of (1) examining the changing nature of self-employment in Cuba between 1998, 2008, and 2011; and (2) assessing the marketing and economic development strategies framing entrepreneurship over time. The Ministry of Prices and Finances denied our requests for a national sampling frame of self-employed workers. Therefore, we used snowball and convenience sampling techniques to reach the target audience. We aimed to get a variety of business types: food preparation, mechanic and electronic repairs, bed-and-breakfast establishments, book vendors, cobblers, barbers, upholsterers, and related self-employment types. These methods are appropriate when working with sensitive information and when formal sampling frames are unavailable (Babbie, 2007). Where the 1998 study drew on workers from Pinar del Río, Havana, and Havana City provinces, the 2008 and 2011 surveys excluded Pinar del Río self-employed workers.

3. Findings

Surveys show that self-employed Cuban workers value their independent work setting, having a steady cash flow, and colocating work and residence. By 2008, only experienced and more educated workers had remained in this labor sector, while by 2011 the sweeping reforms, had ‘opened the gates’ as new and younger workers with less formal education rushed in to seek their livelihoods or strike out on their own after public down-sizing (Table 2). Moreover, the tax/profit percentage rose from 41% to 45% between 1998 and 2008, reaching 47% in the 2011 survey, which underscores the government’s goal of adding to the public till through taxation.

Table 2 Cuban Entrepenir Profiles, 1998, 2008 and 2011, Mean Survey Results.

Source: 1998 data from Peters and Scarpaci (1998); other years from the authors.

Although the number of self-employed workers fell by about one quarter across the island between 1998 and 2008, the 2008 data profiled a slightly older, better educated, and greater compensated group of workers than a decade before. Cuentapropistas earned more than the average Cuban worker and physicians, and they were paying about 10 per cent more in taxes than those in the previous study. With the recent labor liberalization implemented in 2010, the 2011 survey reflects that as more workers entered private businesses, the formal level of schooling and the age of the entrepreneurs fell. Gross income and tax levels changed little. It is noteworthy that in 2011 there were some 340,000 valid private sector licenses (combining the roughly 140,000 in 2010 with the 200,000 new ones issued thereafter) as state workers anticipated downsizing and increasingly opted to get a toehold in the emerging entrepreneurial sector before being left behind (Agence France Presse, 2010).

Our concern here is to focus on a major area of distinction in relation to the question: “What principal challenge does your business face?” Five nominal response categories followed (see Figure 2). Test results for 1998 data produced a Chi-square of 47.58 with five degrees of freedom (p< .001). The same nominal response categories for the 2008 were also significant with a Chisquare of 28.03 (p<.001); we did not ask the challenges question in 2011.

Source: Authors'data.

Figure 2 Major challenges specified by Cuban self-employed workers: 1998-2008 and 2011.

In general, entrepreneurial challenges increased between 1998 and 2008 in the realms of supplies (cost and availability), taxes and licensing fees, and inspectors and regulations. Referring to both inspection and supplies as challenges, a pizza maker/vendor in Eastern Havana stated that that when an inspector arrives at the work site, he/she immediately demands to see receipts for the inputs: flour, eggs, yeast, oil, salt, tomato sauce, and related ingredients. The pizza maker described it thus:

They quickly determine whether my retail receipts are sufficient -never mind they are expensive as all [heck]-and if the inspector doesn’t believe I can document sales, I could be fined, or even shut down (authors’ translation).

He ends his recounting of the matter with the popular Cuban refrain: “Esto no es fácil!” (This isn’t easy!). The pizza maker, like the jeweler described above, is required to buy all his supplies at government shops that charge retail, hard-currency denominated prices. If the pizza maker wishes to add a sample sign that hangs perpendicular to the front of his restaurant (versus a sign in the window, which is free of charge), he will have to pay the municipality a fee for the advertising. Like mundane hip in the former USSR (Rehn and Taalas 2004), viral marketing and proximity between vendors and consumers drive customers to providers and remain the only marketing channels available.

4. Discussion

Following Drucker’s (1958) call half a century earlier, this paper has attempted to isolate and analyze more closely a particular type of entrepreneur. It would appear that nearly 50 years of socialism have not diminished the yearning for self-employment, which challenges Hofstede’s (2001) thinking on non-capitalist based entrepreneurship. A half a century of central planning has created an important space for these workers to provide products and services in ways that the state cannot (Rosenberg-Weinreb, 2009). Although there is no unequivocal evidence that small business owners are more likely to cut corners, underreport, and engage in ‘grey’ activities (e.g., buying on the black market), the temptations are many. An auto body repairman in Pinar del Río put it this way:

“We buy everything from the state, and we buy at retail. It is not fair that those [joint-venture] companies can bring everything in a large container, while we cuentapropistas are mercilessly taxed at high levels. So if some epoxy or quality paint shows up on the [underground] market, the temptation [to buy it] is great!” (Authors’ notes and translation).

The most prominent challenge continues to be getting supplies at low prices (Cruz and Villamil, 2000; Peters and Scarpaci, 1998; Ritter, 1998). Wholesaling remains absent and distribution channels remain limited; cuentapropistas resent these constraints. Supply-chain improvements will no doubt add value to a wide array of products and services (Ritter, 1998). Until June 2012, Cubans living abroad could bring limited inputs for business production back to the island so that small businesses could use those materials; this was duty free. Prior to the new duties on entrepreneurial goods, Cubans scrambled to get supplies onto the island before the deadline.

The number of charter flights from the United States doubled on the final tax-free day; an additional ten flights carried what customs officials described mainly as food items. This reversal of import duties counters a 2008 law that allowed international passengers to enter Cuba duty-free with food if they claimed it was non-commercial reasons (Rainsford, 2012). Paladar operators must now seek pricier inputs from state stores or the black market, no doubt will have to pass those price increases on to clients. This scenario worsened considerably in 2013 when the state issued a clarification of the licenses issued to seamstresses and tailors preventing them from reselling imported clothing in the future and threatening as many as 20,000 such microenterprises with bankruptcy and closure (Valdés, 2013 a; García, 2013; Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba, 2013).

The government also extended this “command and control” posture by outlawing the operations of the innovative entrepreneurs who had set up private 3D cinemas and game rooms making creative use of “operator of recreational equipment” or “paladar” licenses (Espacio Laical, 2013). Moreover, channels of advertising for Cuba’s micro-entrepreneurs are confined to word-of-mouth. Internet marketing strategy is out of reach for all but the most successful cuentapropistas (Freedom House, 2013).

The second challenge is taxes and licensing fees, which has also been reported in earlier studies in Cuba (e.g.Cunha and Campos e Cunha, 2003; Suchman et al., 2001) and elsewhere (Kamleitner et al., 2012). In fact, legislation established since October 2010 require that cuentapropistas contribute a 25 per cent tax on monthly gross earnings to a social security pension fund. State workers do not pay this tax (Martínez and Puig, 2010). As Cruz and Villamil (2000) cautioned, this could lead to a Russian-like situation where entrepreneurs avoid all contact with the legal system (see alsoYurchak 2002). However, Cuban entrepreneurs need the support of a functioning legal system (Cunha and Campos e Cunha 2003). They face stiff tax codes and harsh inspection, which is the third most prominent challenge reported in this study.

As previous literature maintains, for a truly entrepreneurial culture to exist in Cuba, a culture change of significant proportions is required (Nee and Matthews, 1996; Cruz and Villamil, 2000). Sriram et al. (2007) assert that barriers to entrepreneurship are predominated by entrepreneurial motivation and skills. In China, for example, entrepreneurship has emerged as a vital component in the Chinese economy. A shift in the view that profit making and wealth accumulation is socially offensive would be a start (Rosenberg-Weinreb, 2009). As a welder in the Alamar district of Havana reported to us in 2011; “as long as my gold chains stay under my shirt and [are] not shining in the tropical sun, I can trod along with minimal hassle from my neighbors and the inspectors”. This comment may strike scholars who study entrepreneurship in market economies as trivial and banal because they fail to see the impact it has on the functioning of the enterprise. Nonetheless, functioning as an entrepreneur in Cuba necessitates the downplaying of material rewards (gold chains) and cap-tures a central tenet of mundane or everyday entrepreneurship in Cuba; the extent to which such “bling” or ostentatious behaviors are defined remain culturally defined in time and space.

So too does sharing wealth either tangibly or intangibly among neighborhoods and engaging in neighborhood activities sponsored by the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR). This implies attending meetings and occasionally volunteering for all-night neighborhood-watch shifts in front of state stores (that are often targeted by burglars). A shift in the position of the state would be another important step.

Conclusions

Demand for working outside the state system is unprecedented and the legalization of the sale of homes (with a 16% commission charged by the state) and private automobiles (with an 8% tax) will no doubt afford entrepreneurs with capital that is without precedent in Cuba. We contend that at least four impediments must be resolved for the entrepreneurial sector to truly come out of the shadows and contribute to economic growth.

1. The control-intensive approach that has created a list of specific permissible occupations (instead of allowing the flowering of as many kinds of jobs as entrepreneurs can dream up) acts as a significant brake on job creation. Such lists are too narrow to absorb the half a million downsized workers.

2.State-lending agencies may not have sufficient liquidity to provide any significant amount of capital to these new workers. Still, no plans exist for a wholesale market for self-employed workers, cooperatives, or new micro-enterprises. Instead, our preliminary fieldwork shows that remittances (and in-kind supplies) sent from abroad often constitute the required start-up capital for small businesses. This is a great irony given that despite the five-decade trade embargo that U.S. has imposed on the island, Cuban Americans can wire up to $10,000 USD daily to family in Cuba (Morales and Scarpaci 2012; Peters 2012b).

3.There may be insufficient demand or disposable income to support these new enterprises due to the global and island-wide economic down-turn.

4.Extending the categories of permitted self-employment and microenterprise may cannibalize Cuba’s export of professional services, which brings in about $6 billion USD into the economy, more than three times the amount that tourism generates (Martín, 2010). The VI Congress of the Cuban Communist Party in April 2011 signaled the government’s awareness that it needs to take into account its citizens as these important changes take hold. This realignment entails the state’s goals for a socialist society as defined by revolutionary ideals, and the ability to adapt to everyday material needs. However, the Cuban case departs in key ways from transitions from centrally planned economies in the former USSR and China (Liao and Sohmen 2001; Li and Matlay, 2006).

Mundane entrepreneurship in Cuba unfolds at a more guarded pace -“without haste, but without pause” in the words of Raúl Castro- than in the former USSR. SMEs remain tightly regulated; municipalities have only recently been empowered with tax-gathering benefits as in China, where the ‘traditional local government’ has transitioned into an ‘entre-preneurial local government.’ This resulted from their need for financial independence and self-sufficiency and this was set in motion by the economic reforms and fiscal decentralization that took place during the 1980s.

This has not developed in Cuba even though the literature shows that entrepreneurial behavior is not solely the domain of private businesses (Li and Matlay, 2006). Our interviews with municipal government officials (poder popular) indicate that they are interested in getting local tax revenues from entrepreneur fees and licenses to pay for mundane expenses like road repair and trash removal, without recurring to the national government through cumbersome processes.

Following Rehn and Taalas (2004), our discussion of Cuban entre-preneurship and society has focused on a command economy that we believe is also fundamentally an entrepreneurial society. By introducing the case of the Cuban-style blat, cuentapropismo, and newly created SMEs, the paper illustrates how mundane individual economies constitute entrepreneurship and how flexible networks complement Cuba’s command economy. To exclude irregular economies such as Cuba’s from broader discussions of entrepreneurial behavior may be rationalized from an ideological perspective but does not hold up from an analytic perspective.

Evidence of mundane entrepreneurship in Cuba suggests that SMEs could be important elements of change in the process of transition to a market economy and supportive elements in the development of democracy and a strong civil society (Morrison, 2000; Sriram et al., 2007). SMEs could also be framed politically as a step to perfect socialism and shed the complicated ideological baggage that the economy is moving towards capitalism (Morales, 2009).

In fact, the Cuban Communist Party “Guidelines” published in 2010 and ratified in 2011 call for the targeting of “vulnerable groups” (e.g., children, elderly, infirm, women and infants) in a way that the “Chilean miracle” did under General Augusto Pinochet in the 1980s as the socialist welfare state of that nation was being scaled back (Scarpaci 1988; Scarpaci 1989). Witness, for example, the Chinese government’s official 2002 ‘white paper’ on labor and security, in which the word ‘wealth’ is not mentioned a single time, yet the document heralds the average annual (1978-2001) 5% increase in real wages (Government of China, 2002).

Cuba’s mundane entrepreneurship is not antithetical to a socialist agenda, as Vietnam’s trajectory shows. In a recent visit to Havana by the Vietnamese Communist Party chief, Nguyen Phu Trong, Juventud Rebelde, the Cuban newspaper, lauded Vietnam’s “doi moi” economic restructuring, proclaiming it a “process that contemplates introducing the logic of markets into the economy, but with a socialist orientation.” Cuba’s main newspaper, Granma, then ran an interview with Nguyen who claimed the Vietnamese government’s main challenge was “to change the general and individual mentality in Vietnam” in the face of many who “thought that the country intended to abandon socialism.” Cubans are in this “same phase,” he said. History has shown that Vietnam has not abandoned socialism, he asserted, citing Vietnam’s broad-based growth and poverty reduction (Peters, 2012 a: 22). However these socialist economies frame these narratives, we have seen that the development of SMEs is beneficial, perhaps even essential, in transition economies for many reasons.

Unlike the blat system of the USSR, there has been no ‘overnight’ transition to market forces in the Caribbean nation (Dyker 2002), which begs the question: What role is there for SMEs in Cuba’s entrepreneurial realignment? As Cuban workers become increasingly disassociated from the state, they shift from being a vehicle of the Revolution to an entity that must be regulated, scripted, and tightly controlled (Phillips, 2008: 349-350). Driving this shift is a rising political and societal acceptance of material workplace incentives over moral ones.

We argue that a central coping strategy of theirs is to drawn on lessons learned from the island’s mundane entrepreneurship, which has already provided thousands of Cubans with material benefits in a society where material scarcity is rampant. Unlike the Soviet blat system, mundane capitalism in Cuba has received careful government regulation for nearly two decades and remains a keystone in the bridge for a centrally-planned economy to a mixed-market one.

The limitations of this research stem from the inability to secure a sampling frame from the Ministry of Prices and Finance. It would provide the total universe of legal self-employment across the nation’s 169 municipalities, and enable stratified sampling by sector and municipality. Greater sampling of rural, small town, and agricultural enterprises would also provide a richer dimension to mundacity and self-employment. Future research will be able to build on the tangible changes of the possible rapprochement between the U.S. and Cuba based on President Obama’s late 2014 pronouncement. It should examine whether the new post-Panamax container port at Mariel Bay -just west of Havana- encourages wholesaling and invites more commercial traffic to Cuba in a post-embargo era. Research that builds on concepts such as reciprocity, the mundane, and solidarity can enhance our theorization of entrepreneurship, Cuba’s economy of favors, and perhaps even enhance the workings of our own everyday economies.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)