Introduction and statement of the problem

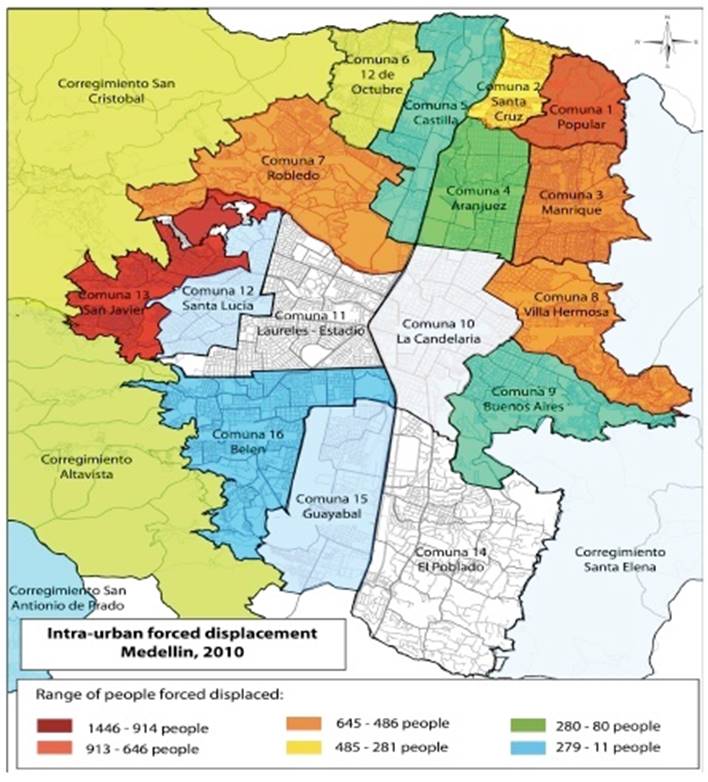

Colombia has a considerable number of internally displaced people, estimated at between 7.7 million and 8.2 million between 1985 y 2018 (UNHCR, 2016; UARIV, 2018), with the majority being victims of the Colombian internal conflict (UNHCR, 2016; Rodríguez y Rodríguez, 2010). As Colombia’s internal conflict, which has been going on for more than 60 years, has fluctuated, the phenomenon of internal displacement has expanded, affecting today’s urban centres (Jacobsen and Kimberly, 2008). Forced displacement has been used as a powerful weapon by opposition groups and armed gangs (Figure 1).

Source: https://rni.unidadvictimas.gov.co/RUV.

Figure 1: Persons affected by displacement by year 1985-2016

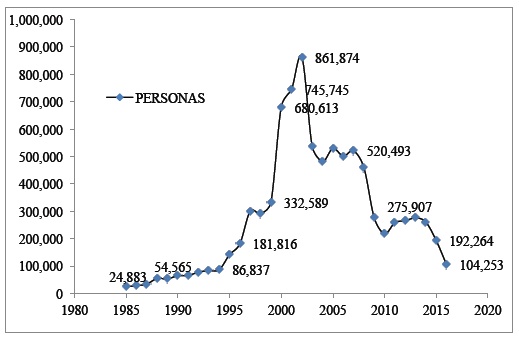

Medellin, the city upon which this research will focus, is the second largest urban area in Colombia, according to the latest census (DANE 2008). According to this census the city had a total of 2.8 million residents in 2016, and a little over 3.7 million people in the surrounding metropolitan area composed of another 9 municipalities. The city is geographically divided into 16 comunas and 5 corregimientos; the corregimientos are the rural areas surrounding the city (Figure 2).

Source: Geo-referenced map of life quality indicators, 2010. Map by Alcaldia de Medellin.

Figure 2: Medellin divided into comunas, corregimientos and neighbourhoods

The growth of this valley, surrounded by mountains, is the result of the massive influx of peasants escaping from different kinds of rural violence or attracted by the promise of better living conditions. The rural violence suffered in the mid-twentieth century drove thousands of people to migrate to the metropolitan areas in Colombia. Medellin was one of the unprepared reception centres that could not handle the fast growth of its population and its social inclusion, causing an outstanding level of poverty and inequality, a consequent clash and disintegration of society, and an increase in the levels of the urban violence (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001).

Since the 1960s, Medellin’s disorganized and unplanned expansion has led to the building of informal neighbourhoods on the mountainsides. Over time, these neighbourhoods have exceeded their limits in terms of size and population. Due to their locations being frequently uninhabitable or environmentally dangerous; the government has neglected them, only providing their residents with basic amenities and the limited construction of health centres, schools and roads (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001).

In the 1980s, the city experienced a crisis in the production of commercial agriculture, mining and trade. This facilitated the emergence of the mafia, as the crisis of the textile factories coincided with the rise of the Medellin cartel (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001).

In other words, recent urban violence in Medellin is the result of the influence of national opposition groups, such as the guerrillas, the paramilitary and the mafia. The violence in Medellin is not entirely the result of the drug trade, as its history is strongly linked to the origins of guerrilla and self-defence groups.

Forced intra-urban and inter-urban displacement has been one of the consequences of the internal conflict in Medellin. In 2010, intra-urban forced displacement reached its highest ever peak, becoming a major social issue that deserves to be studied in order to be prevented in the future. It is a very complex issue, as it is not directly connected to common violence indicators, such as an increase in violent deaths.

Any public policy aimed at the prevention of forced intra-urban displacement should have a clear understanding of the drivers of migration and of how these drivers influence individuals’ decision-making. Prevention is one of the biggest gaps (Weiss Fegen, Fernández, Stepput and Vidal López, 2006) in the application of the internally forced displacement public policy, which was created by the 387/97 law (El Congreso de la República, 1997), and complemented with the sentences and orders given by the Colombian Constitutional Court. This research will contribute to the policy makers´ task of filling in the gaps, with a comprehensive study of the drivers of violence-induced intra-urban migration, highlighting the drivers of intra-urban migration and showing the impact that they have on households’ decision-making processes.

The body of this research will be divided into 3 chapters. Chapter 2 will explain the methodology used and the reasons for selecting the case study research method and the push-pull model as a theoretical framework. Chapter 3 will be divided into two sections. The first section will give a clear overview of the previous push-pull models related to forced migration and the previous approaches to the identification of individual households’ decision making in Colombia. The second section will complement it with a brief description of the history of violence in Medellin, providing the reader with a good understanding of the local conflict and a basis for understanding the research findings.

Chapter 4 contains the research findings, divided into five sections that identify the drivers of intra-urban forced migration in the case of Medellin, as suggested by the model which is to be applied. These sections are: predisposing factors, proximate factors, precipitating factors, mediating factors, and the driver complexes.

Finally, the research will provide an evaluation of the methodology used and draw some final conclusions.

Research aims, approaches and method

The main aims of this case study are to identify the drivers of migration in intra-urban forced displacement, to better understand violence-induced migration in urban areas and to highlight the challenges that any approach focused on preventing forced displacement in Medellin should consider.

Existing research in Colombia identifies the push and pull factors in forced migration decision-making, placing emphasis on migration from rural to urban areas or from rural to rural areas. A key innovation in this study is to link previous research, as an explanation of the Colombian national context of forced displacement, to the case study of Medellin. In accordance with this, we are going to apply a very recent push-pull model (‘Drivers of Migration’), which is thought to provide a comprehensive 3understanding of the context, the environment and the circumstances within which people decide whether to move or to stay. It complements the case study well, and it will allow us to perform an in-depth study all of the factors that influence migration, and to build on the findings of previous studies.

The case study research was selected as the main research method, as a way of testing the ‘Drivers of Migration’ theory with the aim of confirming, challenging or extending its propositions, with regard to the case of Medellin. Indeed, it might result in non-generalizable findings, which is always a risk when studying unique cases. This method is considered to best suit the case of Medellin and the ‘Drivers of Migration’ theory, as this method allows the researcher to explain causal links, real-life complex events and to describe a situation and the context in which it occurred (Yin, 2009).

This method will be complemented with other data gathering techniques, in the form of both primary and secondary research. The primary research consists of our personal observations of the intra-urban displacement phenomenon in Medellin in 2010, when one of us worked carrying out a study on this topic. We will analyse 1 578 testimonies gathered from the forced displaced population during that year. These testimonies explain the particular circumstances in which 5 868 people were forced displaced in the city. As these testimonies have a legal reserve, we will no give specific names or details that can lead to the identification of the victims.

One of us visited the neighbourhoods from which the victims had been displaced, and had the opportunity to speak to both the victims and the perpetuators of violence. It was very difficult to maintain a neutral researcher position between them, as there is a very thin, almost imperceptible line that separates civil society from armed gangs. We will mainly use these primary data with the information collected from newspapers, reports, social statistical analyses, some journal articles and other secondary sources of information, to link what occurred in 2010 with the background events and some recent changes.

The testimonies were collected in the UPDH (Permanent Unit for Human Rights) of the Personeria de Medellin, one of the government agencies in charge of taking statements from the forced displaced people who seek recognition as IDP in order to receive the benefits that this status offers. This analysis will be based on applying a driver’s model from 2012, and will be primarily based on qualitative data. As mentioned above, we will use the fieldwork experience and observation to complement our main source of information: the testimonies.

We will present the findings with a narrative description of the drivers, some simple statistical analysis and a geo-referenced map of the forced migration in Medellin that will give the reader a clear image of the phenomenon and its causes. The use of didactic methodology to present the findings will give the reader a better understanding of the case study.

Literature review

The purpose of this literature review is to present an overview of the state of the knowledge regarding previous push-pull traditional models for explaining the migration decision; highlighting those studies focused on the drivers of migration due violence. The ‘The Drivers of Migration’ model will be theoretically explained as this is the model that will be applied and tested in this case study of the intra-urban forced displacement in Medellin. Finally, a brief review of the violence in Colombia, and particularly in Medellin will be outlined from different research and reliable reports.

Approaches to the drivers of migration

Rather than being correct or incorrect, the models that have been developed throughout history are approaches to a theory that is still under construction, each of them has had influence and has brought new factors to light, which have permitted a comprehensive state of the knowledge of this topic. They contribute to understanding individual decision-making in migration. Nowadays, a combination of these models must be applied. That is the reason for which they will be presented in chronological order, seeking to give the reader a better understanding of how the theory has evolved over time. This section of the literature review will focus on the most relevant push-pull models that seek to understand forced migration, highlighting pertinent material for this case study from particular models and trying to identify the key drivers found by different researchers.

Ravenstein is one of the founders of the push-pull model of migration. He wrote two main articles on migration (‘The Laws of Migration’), the first of which was published over a hundred years ago, but remains mostly valid. His work on migration law was based on the difficulties of interpreting the British census´ place of birth (Ravenstein, 1885). He developed a migration model: 11 laws or hypotheses about how migration takes place. These laws were reviewed in his posterior papers and were tested by other authors in the last century. Almost all of them have been confirmed to be valid (Grigg, 1977; Dorigo and Tobler, 1983). Even though this research focused on voluntary migration, it is significant as it is the first representative model that tried to explain how push and pull factors influence the migration decision.

In 1970, Brown and Moore developed another important model (‘The Intra-Urban Migration Process: A Perspective’), which filled in the gaps regarding the prediction of individual decision-making and its variables. This paper sought to understand the nature of individual responses to environmental conditions in urban areas. It showed that every household has its own behaviour system, which is influenced by its environment. The environment provides a source of stimuli (‘stressors’) to which the household responds. The ‘stressors’ can be disruptive to or can threaten to disrupt the predicted patterns of household behaviour, producing a state of stress. The research attempted to predict ‘in probabilistic terms which people will be adversely affected by a stressful situation’ (Brown and Moore, 1970), as the household´s perception of the environment influences the ways in which households cope with stress and could postpone or accelerate the decision to seek a new residence.

In 1969 Kunz gave a new dimension to the push-and-pull theory as a kinetic model, distinguishing between the movements of free migrants and those of refugee settlers (Kunz, 1973). He advanced the theory, separating voluntary decision-making from forced decision-making. He found that depending on the perceived danger or immanence of the threat, forced migrants have more or less choice. He showed, from a purely kinetic point of view, that anticipatory migrants follow the same pattern of free push-and-pull migration, although the influence of pull factors do not play a main role. On the other hand, acute refugee movements contrast with anticipatory movements in their kinetics and selectiveness: if their push motive is overwhelming, pull factors may be totally absent (Kunz, 1973).

In 1983, Dorigo and Tobler defined push factors as life situations that give people reason to be dissatisfied with their present location and pull factors as the situations or particularities from a different location that seem attractive (Dorigo and Tobler, 1983). They translated the geographer Ernst Ravenstein’s ‘Laws of Migration’ into algebraic form. They verified that the majority of migrants move only short distances and concluded that migrants prefer to migrate to great centres of commerce or industry (Dorigo and Tobler, 1983). This research is one of the studies which focused on testing Ravenstein’s work.

Since the previous research, other models have been built around the world (Gottschang, 1987; Todaro and Maruszko, 1987; Stark and Taylor, 1991). Two of them are relevant to the decision-making of Colombia’s forced displaced population and deserve to be reviewed more in-depth. These pieces of research pointed out that violence modifies traditional push-pull migration models, where pull factors such as incentives of education, location assets and social capital do not determine the migration decision in the same way (Ibañez and Vélez, 2003), as Kunz had established three decades ago. Forced and voluntary migrants compare the costs and benefits of staying or moving out and choose the option with larger net benefits. However, violence modifies the costs of staying and influences the migration decision. As in Brown and Moore’s findings, these models -based on Colombia’s forced migration- assured that the particular characteristics of households, socio-demographic factors and the social context are aspects that influence involuntary displacement.

The first piece of research (2003) stated that in the 1990s in Colombia, massive migration was a common pattern as a reaction to acts of violence. Nowadays, as a consequence of the geographic extension of the conflict, preventive migration is the most common pattern of migration. It showed that illegal groups were the main parties responsible for forced migration; with the paramilitary being responsible for 50 per cent of the cases and the guerrillas for 20 per cent of the displacement in 2001. The research showed how households were more likely to be displaced if they were located where the paramilitary and guerrilla presence was strong and the military presence was weak (Ibañez and Vélez, 2003).

Forced displacement was an important war strategy to gain obedience from the local community, intimidating and impeding collective action from the civilians. Direct threats to household’s members and selective murders were the principal factors that pushed them out. Indirect acts of violence, such as massacres, murders and confrontation was another important factor. Landowners and community leaders were more likely to be displaced, because illegal groups wanted to taking away land illegally and destroy social cohesion. Violent land appropriation was a way to control and expand the territory, to clear up the land from the opponents and to hold, cultivate and use valuable land (Ibañez and Vélez, 2003).

Pull factors, such as having contacts at the place of reception, decrease migration costs as they can provide housing and support for future employment. On the other hand, potential discrimination at the place of reception could increase these costs, as the displaced population is frequently discriminated against in urban centres and is seen as a population that belongs to illegal groups and takes public resources from the poor. Information about economic and social opportunities may increase or decrease the benefits of migration, whilst uncertainties about the receiving place may dissuade people from migrating (Ibañez and Vélez, 2003).

The second piece of research carried out in Colombia was in 2007, and included a more rigorous statistical analysis. Nevertheless, it essentially had the same findings as the previous one, as it advanced the first one rather than offering a totally new theory. This research tried to identify the socio-demographic characteristics that play an important role in displacement caused by violence, as another factor that may influence the decision to migrate. The model proposed that the decision to migrate varied according to individual perceptions of safety that depended on the direct or indirect risks of the violence and on other risks related to the characteristics of every household, such as the social and economic characteristics that may target them or direct threats (Engel and Ibañez, 2007). In other words, a household’s perception of violence may affect or create ‘stressors’, accelerating the decision to migrate.

They identified two types of forced migration that interact with the model and deeply influence the variables. Reactive displacement refers to the migrants who impulsively left the region because they did not see any other way to save their lives; whilst preventive migrants are those who considered the risks involved in staying or leaving before making a decision.

Finally, they suggested that the pull factors identified in previous studies of voluntary migration do not always work as positive attraction, but can also deter the decision to migrate. In this way, larger landholdings tended to deter migration in places with low levels of violence, but increased the probability in places where a high level of violence was found. Those in possession of livestock were more likely to move as they could easily transform it into financial resources to cover the costs of displacement. Unexpectedly, they found that having personal contacts tended to reduce the expectations of living standards after displacement, increasing the costs of migration. The link between the place of origin and personal contacts did not deter migration as people with strong links to the community were more likely to be targeted by illegal groups and hence to be displaced. Nevertheless, a lack of economic opportunities, situations in which basic needs were not met and households with woman or children were factors that promoted displacement (Engel and Ibañez, 2007), as predicted by traditional push-pull models.

From these pieces of research it can be seen that previous models identified some push and pull factors that increase or decrease the people’s motivation to migrate. Voluntary migrants and forced migrants have different levels of freedom in the decision-making process; this freedom can be almost absent in the case of reactive forced migration. Violence plays a major role in decision-making, as it can modify the traditional pull factors in voluntary migration. According to Ravenstein and confirmed by Dorigo and Tobler, migrants prefer to migrate short distances towards urban centres, this is a possible explanation for the intra-urban migration phenomenon. All these findings are crucial for an understanding of this case study.

For example, for Colombia it can be reflected in the migratory balance affected by violence (different from economic motivations): we have few municipalities or departments that reflect positive balances of migration. In this case there are Bogota, Antioquia, Casanare, Guajira, Meta, Cundinamarca, Valle del Causa, San Andrés, among others. But in most of the departments they presented negative migratory balances. I include Dane's projections that by 2020 these municipalities will continue to show negative migratory balances as long as there is no peace in the country (Table 1).

Table 1: Colombia: Migratory net balance 1985-2020

| 1985 1990 | 1990 1995 | 1995 2000 | 2000 2005 | 2005 2010 | 2010 2015 | 2015 2020 | |

| Antioquia | -37 211 | -10 844 | 22 630 | 38 857 | 38 635 | 39 373 | 40 404 |

| Arauca | 16 527 | 16 248 | 12 461 | -13 173 | -13 173 | -13 173 | -13 173 |

| Atlántico | -1 736 | -1 960 | -26 227 | -23 361 | -13 941 | -8 821 | -7 034 |

| Bogotá | 263 931 | 260 001 | 117 106 | 81 258 | 79 188 | 79 113 | 81 391 |

| Bolivar | -2 168 | -2 802 | -77 569 | -92 099 | -64 171 | -40 592 | -31 880 |

| Boyacá | -79 952 | -85 466 | -76 430 | -74 574 | -68 348 | -60 241 | -51 128 |

| Caldas | -41 347 | -43 811 | -53 448 | -47 462 | -41 123 | -36 224 | -30 610 |

| Caquetá | 456 | 491 | -26 603 | -23 669 | -15 071 | -11 821 | -10 791 |

| Casanare | 1 103 | 6 143 | 4 105 | 3 391 | 3 105 | 3 019 | 3 019 |

| Cauca | -15 525 | -26 249 | -46 399 | -50 800 | -44 030 | -33 778 | -36 136 |

| César | -17 282 | -25 916 | -41 012 | -36 704 | -29 088 | -27 794 | -27 439 |

| Cocó | -32 786 | -33 359 | -36 922 | -35 571 | -33 823 | -31 469 | -28 512 |

| Córdoba | -48 842 | -49 761 | -38 799 | -36 392 | -27 157 | -14 631 | -11 035 |

| Cundinamarca | -33 803 | -35 980 | 23 158 | 33 613 | 36 936 | 40 083 | 43 380 |

| Grupo amazonia | 3 794 | 3 921 | -237 | -10 997 | -12 907 | -13 641 | -12 817 |

| Huila | -26 660 | -26 878 | -25 053 | -17 001 | -13 706 | -13 368 | -14 176 |

| Guajira | -9 942 | -11 392 | 28 506 | 51 765 | 38 257 | 29 872 | 22 688 |

| Magdalena | -25 993 | -49 375 | -80 984 | -75 563 | -62 614 | -51 392 | -40 270 |

| Meta | -9 059 | -9 206 | 20 254 | 21 320 | 21 474 | 22 911 | 24 646 |

| Nariño | -30 909 | -39 278 | -46 601 | -35 075 | -26 142 | -14 184 | -10 142 |

| Santander | -29 442 | -20 644 | -54 590 | -47 167 | -37 508 | -29 550 | -27 526 |

| Putumayo | -1 998 | -5 053 | -11 431 | -18 658 | -16 952 | -13 310 | -8 890 |

| Quindio | 5 477 | 6 160 | -17 387 | -15 509 | -12 748 | -11 098 | -8 666 |

| Risaralda | 15 493 | 19 472 | -27 814 | -23 840 | -21 048 | -19 037 | -15 743 |

| San Andrés | 5 008 | 5 015 | -2 434 | -2 432 | -2 070 | -1 459 | -1 008 |

| Santander | -45 751 | -46 866 | -73 067 | -77 669 | -63 353 | -57 866 | -50 062 |

| Sucre | -19 866 | -20 451 | -36 815 | -32 802 | -26 555 | -22 589 | -18 372 |

| Tolima | -88 305 | -88 449 | -78 245 | -68 736 | -60 839 | -57 011 | -52 900 |

| Valle del Cauca | 41 201 | 48 025 | -53 496 | -32 101 | -10 611 | -2 644 | 10 088 |

Source: http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/series-de-poblacion (MN, porcentaje de migrantes netos)

The models described above made numerical, statistical, arithmetical or econometric analyses of the push and pull factors, using the methodology of conducting surveys or analysing data from other sources. They focused on individual household decision-making and its close environment; the factors which are more likely to be included in equations for predicting the human behaviour.

Although the research on forced displacement and the migration decision carried out in Colombia is comprehensive and its findings are reliable and in accordance with the reality of the situation, little has been said about the intra-urban forced migrants’ decision-making process and its drivers. An analysis of the general context (not only of the proximate household environment) of the forced intra-urban out-migration phenomenon should be studied at the same time, as suggested by the ‘Drivers of Migration’ (2012) theory.

The Migrating out of Poverty model or theory identifies the drivers of migration as ‘the factors which get migration going and keep it going once begun’ (Van Hear, Bakewell and Long, 2012). This combination of factors shapes the environment and the circumstances within which people choose whether or not to move. These drivers operate in different ways and adopt different patterns, depending on the ‘drivers’ complexes’. The ‘drivers’ complexes’ combine configurations of the locality, geographical scale, duration or timeframe and the depth or tractability of the drivers in every society or population (Van Hear et al., 2012). The drivers are:

Predisposing factors contribute to the creation of a context in which migration is more likely. Examples include structural disparities between places of migrant origin and destination shaped by the macro-political economy. Such predisposing factors are outcomes of broad processes such as globalisation, environmental change, urbanisation and demographic transformation.

Proximate factors have a more direct bearing on migration and derive from the working out of the predisposing or structural features. In countries and regions of origin, they could include a downturn in the economic or business cycle, a turn for the worse in the security or human rights environments, or marked environmental degeneration, including the effects of climate change. In places of destination, proximate factors might include opportunities that open up as a result of economic upturn.

Precipitating factors are those that actually trigger departure. They may be found in the economic sphere, including financial collapse, a leap in unemployment, or the disintegration of health, education or other welfare services. Or they may be located in the political or security sphere, and include persecution, disputed citizenship, or outbreak of war. ‘Natural’ or environmental disasters can also be precipitating factors. This is the arena in which individual and household decisions to move or stay put are made.

Mediating factors enable, facilitate, constrain, accelerate, diminish or consolidate migration. Facilitating factors include the presence and quality of transport, communications, information and the resources needed for the journey and transit period. Constraining factors include the absence of such infrastructure and the lack of information and resources needed to move (Van Hear et al., 2012).

Without pretension to exhaustiveness, these arguments can be approximated, for the Colombian case, by means of a linear regression model:

Where:

β0: mean of Y when all Xi are zero (when Xi = 0, it is interpreted as the mean of Y that does not depend on Xi).

βi: change in the mean of Y when Xi increases one unit, remaining the other Xi constant.

Then, Y = PREX (expelled people), X1 = POOR (municipal poverty) X2 = POBT (total municipal or departmental population); X3 = PREC (municipal or departmental received population).

The regression model was processed using the statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS© 21). The results are shown in the Table 2.

Table 2: Model summarya

| Model | Variables in model | Variables not in model | Method |

| 1 | PREC, POBT, POBRE b | Forward |

aDependent variable: PEXP

b All request variables entered.

The model presents a good level of confidence (80 percent) and the coefficients such as poverty act positively in relation to those of people expelled, in a negative way to the growth of the population and positive to that of the people received. This is not conclusive, we need to carefully review the hypotheses presented here in relation to the theory and that qualitative work is needed for this. For this, they will be reviewed in detail in the next sections of this text (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3: Model summarya

| Variable | Value |

| R | 0.907b |

| R squared | 0.822 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.801 |

| Std. Error of the estimate | 125679.570 |

| Statistics of change | |

| Change in R-squared | 0.822 |

| Change in F | 38.540 |

| df1 | 3 |

| df2 | 25 |

| Sig. F | 0.000 |

| Durbin-Watson | 2.184 |

a. Dependient variable: PEXP.

b. Predictor variables: (Constant), PREC, POBT, POBRE.

Table 4: Coefficientsa

| Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

||||

| Model 1 | B | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 4602.408 | 41052.831 | 0.112 | 0.912 | |

| POBRE | 0.168 | 0.151 | 0.321 | 1.112 | 0.277 |

| POBT | -0.079 | 0.038 | -0.437 | -2.065 | 0.049 |

| PREC | 0.967 | 0.177 | 0.895 | 5.472 | 0.000 |

aDependiente variable: PEXP.

The ‘Drivers of Migration’ do not rely on econometric analysis, but on a description of the context and of the environment on various levels. The previous investigations succeeded in identifying precipitating and mediation factors, but they failed to recognise the predisposing and proximate factors that impact migration. Therefore, this model was selected in order to find out what the key drivers of the intra-urban forced migration phenomenon are, as it gives a more comprehensive view of all of the factors that can influence migration, although it could be influenced by the researcher’s subjectivity.

The background of the Violence in Medellin, Colombia

The conflict in Colombia goes back to more than 60 years ago (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001), when armed opposition groups formed in response to the 1948 assassination of the liberal political leader Jorge Eliecer Gaitan. The left and right wing parties started a civil war; combat was spread across the whole country. The liberal and communist parties started to consolidate the guerrilla forces by bringing communist militants and self-defence peasants together as an opposition group against the government (Amnesty International, 2004). This civil war lasted from 1948 until the mid1950s, when it ended with a peace pact; the political parties agreed on sharing power. The political agreement was called the National Front, which lasted from 1958 to 1974; it calmed political passions and maintained the basic democratic institutions bringing peace to the country (Gutiérrez, 2003).

Nevertheless, this agreement undoubtedly contributed a great deal towards making the scene worse due to poor participation of the left wing in government affairs and the poor distribution of land, which allowed the guerrillas to continue expanding and consolidating their own ideals. As Thomson points out, the key driving forces behind the Colombian conflict are the longstanding agrarian struggles from the development of capitalism. Indeed, he outlines that the violence in Colombia began long before the drugs trade, although the drug economy transformed the conflict and strengthened armed groups (Thomson, 2011).

Controversially, Gutierrez states that the Colombian war officially started in 1983, when guerrillas posed a political threat to the government. He states that drug trafficking became a key problem in the country that same year, and guerrilla groups -in order to finance their war- took major income from trafficking and taxing crops and sales, although this was not explicitly in collusion with the ideals of the opposition (Gutiérrez, 2003).

On the other hand, in order to restore normalcy in the country, the government decided to foster the creation of self-defence groups and establish their legal basis by issuing the Legislative Decree 3398 and the Law 48 of 1968. These laws allowed the groups to use weapons that had been only granted to the Armed Forces in the country beforehand. From the numerous cases in which links between the members of the Security Forces and the paramilitary groups were found, it became quite apparent that the government had been supporting these groups in a sort of direct or indirect manner (Inter-American Court of Human Rights, 2005). In view of this, it is clear that self-defence groups had misdirected their main objectives and had turned into criminal groups committing crimes against the civil population.

Similarly, since 1960, gangs have existed in Medellin (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001). Initially they had a different modus operandi; they were relatively small and had low visibility. During the 1980s Medellin experienced representative migration from the rural areas to the city; unfortunately the social inclusion was not positive, since the city also suffered from an economic crisis in basic areas of production (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001). Urban conflict intensified and led to the consolidation of drug trafficking and the appearance of the mafia: the Medellin cartel.

Melguizo and Cronshaw (2001) produced a comprehensive analysis of Medellin’s armed groups that coexist in this urban area, upon which this research will rely, as there are not many published articles about the history of violence in Medellin. The article manifests that at the end of the 1980s, militia groups (a hybrid combination of guerrillas) emerged in the north-eastern of Medellin (one of the areas traditionally forgotten by the state), as a response to the expansion of the drug trade and territorial control and a general need for self-defence against criminal incursions.

Melguizo and Cronshaw go on to explain that after the 1980s, the violence in Medellin reached its biggest peak and the city suffered from the assassinations of political leaders by right wing extremist groups, crimes against indigenous people by social-cleaning groups, confrontations with the Medellin drug cartel, crimes by militia groups and massacres by the paramilitary. As a result, armed gangs became part of the social structure of youth socialization and supported professional criminal associations.

In the territories under their control, they were the supreme authorities, controlling decision-making, demanding respect and obedience from the local population and settling social conflicts. Some groups displaced others in disputes over territorial control (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001). These groups have evidently contributed to the demarcation of territories, borders and zones of authority in the city.

The precarious upholding of the law, general insecurity and the inefficient legal system led armed gangs and a few militia groups (who have now almost disappeared in Medellin) to impose security services on the neighbourhoods of Medellin and collect illegal ‘taxes’ or extortions as compensation (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001). There was a reproduction of the national armed confrontation at a local, neighbourhood level.

As a result, militia groups grew in an overwhelming manner and proclaimed themselves the armed power of the neighbourhoods. In 1994, the government signed an agreement with the militia groups, who promised to demobilize their men and turn in their weapons. Nevertheless, dissident groups remained intact and continued the war. The militia which had been reincorporated was killed in the following years and the remaining militia groups gradually lost their revolutionary ideology and political rhetoric, sliding back into criminal activities and turning into gangs (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001). Nonetheless, as long as the guerrillas exist there will also be militia groups connected to their activities on a micro level in the Medellin neighbourhoods.

Girardo, whose work complements that of Melguizo and Cronshaw, states that the second highest peak of violence was in 2002, when 80 per cent of the national average of homicides occurred in Medellin, and 93 per cent of massacres and 70 per cent of kidnappings occurred in Antioquia (Medellin’s county). Medellin could be said to be under internal conflict, following international parameters designated for whole countries (Giraldo Ramírez, 2008). ‘Medellin was at war’ as Salazar mentioned in his research on gang culture in the late 1980s and early 90s (Salazar, 2002).

The urbanization of the violence occurred as a result of a strategic decision made by the parties involved, the permeability of the region and the local criminal microstructures (Giraldo Ramírez 2008). Some of the armed gangs located in urban areas have links to armed gangs on a national scale, as satellites of bigger organizations (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001; Salazar, 2002), As a result, the extortion or collection of illegal ‘taxes’ became a generalized practice amongst illegal groups.

This caveat is echoed by Melguizo and Cronshaw, who argue that the conflict generated has prevented the consolidation of the sovereignty of the state and the competition of alternative powers or counter-state powers (‘guerrilla groups and some of the urban militia operations’), parastate powers (‘self-defense and paramilitary groups’) and organized crime (‘drug cartels, groups that supply the chemical prerequisites for drug processing, money-laundering groups, arms traffickers, and so forth’) (Melguizo and Cronshaw, 2001).

Findings

This chapter will explain the research findings, after applying the ‘Drivers of Migration’ theory, to the case of the violence in Medellin, Colombia, in 2010. The model’s factors or drivers will be complemented with their ‘driver complexes’, as drivers do not work in isolation to initiate movement or to shape it once underway. The drivers commonly work when combined, and are usually termed ‘driver complexes’ (Van Hear et al., 2012).

Predisposing factors

In the local context of Medellin, the fact that there is a high probability of migration is directly linked to the national context of internal conflict (Figure 3). Even though Medellin has its own history of violence, mafia, drug trafficking and armed gangs, the national groups permeated local actors and changed their traditional modus operandi, as described in the literature review chapter. Their main violent practices and war tactics were copied from those of the guerrillas and the paramilitary (Giraldo Ramírez, 2008). Militia groups trained young people in camps in Medellin, not only imbuing them with the communist ideology, but also preparing them for armed combat (Salazar, 2002). One of these common war strategies related to the stronghold of territory is forced displacement. As Ibañez and Velez mention in their research, the guerrillas and the paramilitary were responsible for 70 per cent of the forced displacement of those interviewed in 2003 (Ibañez and Vélez, 2003).

Source: https://rni.unidadvictimas.gov.co/RUV

Figure 3: Fifteen towns with the highest number of people expelled from Antioquia, 2017

Forced displacement is a strong weapon, used to intimidate and seek obedience from the local population and arguably for maintaining ‘sovereignty’ throughout the territory. Armed gangs are the authority; they decide who lives in the territory which they control.

Colombia’s history of forced migration is directly linked to the history of violence. Unfortunately, there are no reliable records of this long-standing displacement. Colombia only began to register its IDP in 1998, after the implementation of the Law 387/97 (El Congreso de la República, 1997), which is the IDP general framework or regulation. Nevertheless, it is calculated that from 1946 to 1966, two million people were forcefully displaced, and, more recently, between 1984 and 1995 600 000 people became victims of displacement (Rodríguez Garavito and Rodríguez Franco, 2010). According to UNHCR (2016), Colombia has one of the world’s largest populations of IDP, after Siria, with 7.7 million of forced migrants, mostly internally displaced.

As displacement has become such a powerful weapon of war, the decision to migrate has also become a very common mechanism for survival. Colombian people have become more familiar with this phenomenon, which has created a context in which migration is a common pattern for those who live in high-conflict regions, perhaps because many Colombians have not had a day of peace for many, many years.

It is difficult to compare the forced rural-urban or rural-rural migration data with the intra-urban migration data for two different reasons. Firstly, because displacement in Colombia is understood to be a consequence of the internal conflict and the internal conflict is seen as the result of the appearance of armed opposition groups located mainly in rural areas. The only displaced people recognized by the government as IDP were forced migrants from rural areas where guerrillas or the paramilitary were fighting. Fortunately, after the Constitutional Court’s T-268/03 decision (Corte Constitucional, 2003), the Colombian government started to recognize some of the intra-urban migrants as IDP.

This comparison is also difficult because intra-urban forced migrants have slowly gained an awareness of the possibility of being recognized by the government as IDP, enabling them to have access to humanitarian aid and other benefits. This is an administrative process that takes time (normally between 1 and 6 months, depending on the administrative remedies, if they are used). This is in spite of that fact that migrants in urban areas usually have more access to information and to the media and are therefore more aware of their rights than those in rural areas.

However, it is easy to find data concerning recent years in a few of Colombia’s cities with intra-urban IDPs. Medellin is one such city; more accurate data can be found as a result of its having a unique government agency designated to protect human rights: The UPDH of the Personeria de Medellin. According to the UPDH, in Medellin in 2010 the records for people with IDP status reached its highest peak, with 5 868 people displaced, an increase of 582.3 per cent from 2008 to 2010 (Ocampo González et al., 2010). In contrast, across the nation records showed a steady decrease in the number of officially recognized displaced people between 2007 (337 938 people) and 2011 (102 956 people) (Acción Social, 2011). It is important to point out that Accion Social (currently known as Unidad para las víctimas)’s official number of IDP is less than the number of people actually registered as IDP, as not all of the IDP are granted with the official status and the benefits that this would entitle them to.

The Medellin data differs from the national data because Medellin has its own dynamic of violence and is fighting its own battle for control over drug trafficking, running a different course from the rest of the nation. The ways in which the armed groups in the city enforce territorial control affect the personal security of the citizens of Medellin, which varies according to the intensity of the control and of the territorial disputes. It has been shown that if a criminal network were to have complete hegemony in the city, there would be fewer disputes, murders and less forced displacement (Giraldo Ramírez, 2008).

There is a strong relationship between territorial disputes and forced displacement, as a shift in power is traumatic for the local residents and the level of territorial control increases during the band’s process of solidification of the territory. They may infringe on more human rights in order to gain respect and obedience from the locals.

Nevertheless, in 2010 the level of murders decreased by 8.5 per cent (going from 94.4 to 86.3 per 100 000 inhabitants), but displacement still increased. This was because, in order to reduce the high rates of murder in an action apparently coordinated with the Police, armed gangs decided to use forced displacement as a way to clear out the territory which was in dispute, instead of using the strategy of homicide which was predominant in the early 1990s.

When armed gangs do not get the obedience they desire from the locals, they use threats to make households or individuals move out, as a strategy to maintain control and convince the rest of the people not to revolt. In 2010, the comunas Popular and San Javier were the places with the highest rates of displacement because, at that same time, they were disputed areas (Arco Iris, 2012).

On the other hand, the general context showed a Medellin virtually divided in ‘two cities’: the city of opportunities and wealth and the city of the poor. Inequality is overwhelming in Medellin. In 2010 the ICV (Quality of life indicator) index in El Poblado, the wealthiest comuna, was 92.76 points, showing a difference of 16.49 points with one of the poorest comunas, Popular, which had an index of 76.27 points. If El Poblado is compared with the poorest corregimiento, Palmitas, there a difference of 27.05 points in the quality of life indicators can be seen (Departamento Administrativo de Planeación, 2011).

The following maps (Figure 4 and Figure 5) show how forced displacement affects the population of neighbourhoods with low quality of life indicators, whilst the neighbourhoods with a high ICV are almost completely unaffected.

Looking at the unemployment data from 2010, the gap between the ‘two cities’ becomes even clearer. Comunas with the lowest ICV also have the highest levels of unemployment. Once again, comparing the Popular comuna with El Poblado, the former has an unemployment level of almost 20 per cent (19.55 per cent), whereas the latter has an unemployment level of 4.81 per cent.

The general unemployment rate for the whole city in 2010 was 13.71 per cent, higher than the national rate of 10.2 per cent. In general, poor young people and women were most affected by unemployment (DANE, 2011).

In addition, the population per socioeconomic strata is also a decisive factor which widens the gap. 79 per cent of the population of Medellin live in low socioeconomic strata and only 21 per cent of the population live in the middle, upper or high socioeconomic strata (Departamento Administrativo de Planeación, 2011).

Along-standing lack of opportunities, poverty, inequality, unemployment and a strong influence of the mafia culture (Salazar, 2002), permeated Medellin during the 1980s and early 90s. These factors have permitted the propagation of armed gangs and the easy recruitment of the young to these illegal bands, especially in the poorest comunas of the city. The internal conflict in the city and the drugs trade have become some of the main creators of employment (Salazar, 2002). Consequently, there is a strong link between poverty and forced displacement.

Proximate factors

Since 2008, Medellin has had a reconfiguration of criminal power, which was in the hands of The office; a powerful criminal macrostructure that worked as the centre of a smaller network of armed gangs and mostly controlled drug-trafficking throughout the city (Arco Iris, 2012). The reconfiguration started when its former head alias Don Berna (Diego Fernando Murillo Bejarano) was extradited to the United States.

After the death of Pablo Escobar, the former head of the Medellin criminality, Don Berna gained control of The Office. It has been said that Don Berna offered invaluable information that helped Pablo Escobar’s persecution by the police, which ended with his death in 1993 (Arco Iris, 2012). Pablo Escobar was known as the Colombian drug lord, he made the biggest fortune and became the wealthiest man in world from trafficking drugs (McCoy, 1998).

None of Don Berna’s direct successors could maintain control over the structure after his extradition. Two of the third generation successors: alias Sebastian (Erick Vargas) and alias Valenciano (Maximiliano Bonilla) started a war in order to gain control of the city. Both of them made strategic alliances with local and national (guerrilla and paramilitary) criminal structures, to get more power and further financing (Arco Iris, 2012). From 2008 to 2009, this local conflict caused an increase in the number of murders; from 1,066 to 2 186. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, the number decreased to 2 023 in 2010 (Personeria de Medellin, 2011). Additionally, it caused a continual increase of intra-urban displacement until 2010.

This decrease in the number of murders in 2010 was the consequence of several factors. Firstly, at the beginning of 2010, when the clashes between the fighting parties worsened, an independent peace commission, which did not have the government’s full approval, tried to negotiate a truce between the opponents with some success. Sebastian and Valenciano made a peace pact, but it only produced a temporary reduction in the number of murders (Arco Iris, 2012). In spite of the truce, Sebastian and Valenciano continued their dispute in order to gain control of Medellin and, after March, the number of murders started to increase again (Personeria de Medellin, 2011). Nevertheless, with the aim of maintaining a low level of murders, the old strategy of forced displacement was used, as explained above.

Individual forced displacement was intensified by illegal groups in order to maintain territorial control, in places that did not experience a shift in power, becoming the cause of 90 per cent of the forced displacement. Meanwhile, massive or collective forced urban displacement was used in order to gain control in the second half of the year by both factions of The Office in Medellin, with the collaboration or connivance of the Police. Six massive displacements of ten or more households or 50 or more people occurred in comunas 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8. Also, six collective displacements that did not configure a massive one, but were caused by the same parties, were located in the comunas 1, 8 and 13. Hence, 581 people were displaced under the same strategy.

It is possible to find similar patterns in all of the cases. In the days prior to the displacement, the police captured some of the armed gangs’ members, and the head of the illegal group was murdered. The next day a large group of people, who were not members of the group that would take control of the territory, but members of the same criminal network as Valenciano and Sebastian, entered the zone, armed with big sticks and machetes, and displaced those households or individuals apparently linked to the opposition, occasionally taking away their property. Many of the testimonies contain information about the police’s logistical collaboration with the criminals.

The disputes over the control of Medellin occurred because the criminal network that controls the periphery of the city also gains control of the channels through which drugs are transported in order to be exported. The nearest port to Medellin is in the same county, in the Uraba region, which is one of the most fought-over regions in the country, because of its location and the richness of its natural resources. Meanwhile, the criminal group that gets control of the centre of Medellin also gains control over the local drug trade.

Consequently, for criminal groups it is more important to gain control of the neighbourhoods located at the top of comunas 1, 3, 6, 8, 7, and 13. That is why these comunas were the most fought-over territories and had the highest forced displacement rates in 2010.

Precipitating factors

As suggested by Engel and Ibañez, the division of forced displacement into reactive and preventive migration allows for an easier and clearer understanding of the individual household decision-making process. However, contrary to their findings, it was shown that in the case of intra-urban displacement only two per cent of the intra-urban displaced migrants had a preventive motivation for migrating. On a national scale, as mentioned by these authors, preventive migration was the most common pattern (Engel and Ibañez, 2007).

This fact suggests that people in urban areas try to cohabit and to resist general violence. Only a very low percentage of people had the relative freedom to decide whether or not to migrate to somewhere within the city. On the other hand, the vast majority of intra-urban displaced people moved out as a result of direct violence against a member of the household or an acquaintance. It is worth clarifying that almost every displaced household or person had more than one motive of migration. Nevertheless, the analysis of the drivers was made taking the predominant motive as the main driver in the decision-making process. Sometimes it was not easy to identify it, but in most of the cases it was clearly found in the migrants’ testimonies.

The drivers found in the testimonies were grouped into categories, to make it easier for the reader to comprehend the precipitating factors. The identified categories demonstrate the ways in which armed gangs violently control the territory; this can be understood as territorial, social or economic control. Social control was the control that armed gangs imposed in the social sphere, enforcing social and moral codes to be adhered to by the local population. Economic control was the control over legal or illegal, public or private economical resources, for the gangs’ own financing. Finally, territorial control per se was a combination of all of the abovementioned factors, but specifically the spatial control aimed at maintaining and protecting the territory already appropriated, or expanding it.

The most common practices for social control were the generation of fear in the local community with indiscriminate attacks on civilians, the co-optation of civil organizations and participation in them, the resolution of community and family disputes, the offer or imposition of their services of surveillance and security, the provision of social needs subventions, and the imposition of curfews.

Economic control consisted of extortions to transporters, traders, convenience shops and inhabitants, as a payment for surveillance activities, the management of places for drug selling and distribution, the management of prostitution centres and constitutions of networks for sexual exploitation of children and women, the co-optation of public resources through local government programs, people’s property dispossession for surveillance activities, the selling of drugs, or for private use, the loaning of money with high interest rates and money laundering through investments and businesses.

Finally, territorial control mainly constituted the following practices: the creation of virtual boundaries in ‘their territory’ for locals, authorities and public servants, the surveillance of people entering or exiting their imposed virtual boundaries, the recruitment of children, young people and adults, the community constraint for collaboration, the co-optation of authorities seeking for their posterior connivance and collaboration, surveillance activities, and forced displacement as a strategy for the protection, conservation and expansion of the territory.

The description of these control mechanisms shows identified elements of the daily performance of the armed gangs in Medellin. Unfortunately, it shows how the affected local population is subjugated by an illegal power; any violation of the impositions or further disagreement with power would cause their forced displacement or even their death, as will be explained in the following paragraphs.

When an armed group found some kind of resistance to one or several of the previously mentioned methods of controlling their territory, the gang mostly used death threats (57 per cent) to producing forced displacement. These threats were either directed at the whole household or at one of its members. Those threatened were usually given two options: death or displacement. It is important to mention that when these threats were the main motive for displacement, they were always accompanied by one of the other drivers mentioned, increasing their percentage when analysing the second and third reasons for migrating.

After threats, the second and third manifestations of territorial control were the homicides or attempted homicides of one of the household members or of an acquaintance, 8.7 per cent and six per cent of the migrants respectively, were displaced as a result of this. In the fourth and fifth place, confrontations between armed bands or armed bands and the authorities (4.6 per cent) and the forced recruitment of adults or children (4.6 per cent) were found to be motives for migration. Physical aggression against a member of the household, with or without personal injury, was another major factor for migration (3.6 per cent), followed by the dispossession of property (2.7 per cent).

On the other hand, generalized fear was only found to be the principal motive for migration in two per cent of the testimonies. Consequently, considering generalized fear to be a preventive motive and an indirect threat to the safety of the household, it becomes clear that there is a strong resistance against being displaced from urban areas. It is also likely to be one of the motives for their staying in the same city.

Significantly, for 1.7 per cent sexual violence was the main motive for migration. Other less common reasons for migration were extortions, the forced collection of debt, constraint to break the law, being accused of being informers or of co-operating with other gangs or with the authorities, theft, kidnaping and retaliations.

For the population of Medellin affected by these controls is difficult to cope and resist the adverse conditions. They have to deal with two different powers, the official authorities and the illegal power, both displaying their own kind sovereignty over the same territory. The consequences for the locals are immeasurable; they pay taxes to both parties and must appear faithful to both establishments, even though they are not compatible.

Neighbourhoods strongly affected by poverty are controlled, disputed over or co-opted by gangs. Sometimes, new gangs are formed in order to maintain the independence of the neighbourhood or sector from the incursions of strangers. In these cases, it was possible to find a high level of support from the inhabitants to the local gang as the gang assured their protection and that of their possessions. When they start to provide subvention to local needs from the money they get from the collection of ‘taxes’ from commerce, this is even more apparent.

Nevertheless, it is very difficult for these groups of young gangs to remain independent without being recruited by big criminal networks or receive higher incomes from the drug trade. Additionally, as they become more armed it is difficult for them to maintain a hierarchy inside the organisation, avoiding the extra-limitation of their power and therefore loosing support from the locals. As this happens, gangs, in order to maintain their control, increase the social and territorial control practices with curfews, moral codes, a stronger inherence in private disagreements, the imposition of virtual boundaries for locals and outsiders, forced recruitment and intense surveillance activities.

The level of people’s subjugation becomes so strong that in some cases it completely modifies the family relationship, both internally and with its environment. Sometimes households give in to the irregular power and start to become part to the counter-state power itself (as a consequence of a long process of normalization of their illegal activities). In other cases they resist or migrate.

Mediating factors

This section explains the factors which accelerated and consolidated the decision of the forced migrants. After more than 60 years of internal conflict, up to 8.2 million IDP (UARIV, 2018) and 340 000 refugees (UNHCR, 2017), it is undeniable that in Colombia there is a culture of migration, of escape from conflict, and that the weapon of displacement as a strategy for illegally controlling the territory, is used by opposite criminal powers and armed gangs, at both a national and a local level.

On the other hand, as analysed in the previous section, it was found that there was a strong resistance to moving out of the urban area of Medellin city. It is clear that migration was only considered as a last resort, because for 98 per cent of the forced displaced households during 2010, it was only when they received a direct threat against their lives or personal integrity that they decided to move out. Analysing this statistic, it is also possible to conclude that moving to somewhere within the same geographic boundaries could consolidate and facilitate the decision of migration.

People in urban areas usually have access to local communication systems and create vast social networks. This also accelerated their decision to migrate, as they usually had someone to help them during the process of establishing themselves in a new area, searching for a place to live, finding new schools for their children, and looking for new jobs in the cases where the displaced worked within the areas from which they had been exiled.

It was found that people recently displaced from rural areas to the urban area were less likely to have constructed social networks able to help them through the migration process and its posterior phases of establishment. Nevertheless, as they were not long established in the expulsing areas, they showed themselves to be less attached to the neighbourhood and their incipient social networks.

For both categories of intra-urban migrants; the already displaced and the recently displaced, national and local government aid is available. However, national aid would cover no more than 50 per cent of the cases (Ocampo González, Naranjo Quintero and García Arcila, 2010), whilst local aid has a wider extension. The local government frequently offers the intra-urban displaced immediate humanitarian aid and shelter, when the displaced show that they do not have social networks able to accommodate them during the transition period. Nowadays, many people are aware of this system of humanitarian aid and people register themselves in order to get the corresponding benefits from the government. The possibility of receiving humanitarian aid from the government and the offer of shelter could also consolidate the migration decision-making.

In Medellin, the displacement was mainly of individual households (86 per cent), followed by massive or collective displacements (9.9 per cent) and some individuals (4.1 per cent). The fact that households make the decision to migrate as a whole family is related to the fact that people do not migrate as a preventive measure for a possible threat against one of the members. They only move when the threat materializes, and the entire household is at risk of being affected. The threats were usually directed against all members of the household.

On the other hand, an analysis of the composition of the households shows that they were made up of women (29 per cent), men (21 per cent) male children (18 per cent), female children (16 per cent), male adolescents (ten per cent) and female adolescents (eight per cent). This fact suggests that women make the decision to migrate more frequently, in order to protect their children and teenagers, to prevent their forced recruitment by illegal groups. It also shows that households made up of male teenagers and children are slightly more at risk of being displaced. Besides, it was shown that when a woman is at the head of the household the risk of being displaced increased.

To conclude, households with women as the head of the family and with male children are more prone to be displaced and the decision to migrate might be made more often than it would in a household with a male as head. The decision was frequently made after the murder the male head of the household or a male son. All these data coincide with previous models’ findings.

Locality:

The drivers found are very dependent on or associated with the specific characteristics of the conflict in Medellin: the influence of the national conflict, the boom of drug trafficking and the permeation of local gangs by the drug trade. The rapid propagation of armed gangs in Medellin has its roots in the deep inequality and poverty that divide Medellin into two cities, one that is hardly affected by displacement and another where forced displacement is a natural path for its residents. The map of the gangs coincides with both the map of poverty and the map of displacement.

However, as Salazar mentioned, it is important to analyse Medellin’s society and culture in order to explain the easy and fast propagation of armed gangs. The paisas, as the people are informally called, were the colonizers of the valley, the colonizers that wanted to get land, money and to generate profits. They were identified as smugglers. The paisas’ values are audacity and astuteness; they are always focused on getting money easily, obtaining the ends regardless of the means. In Salazar’s opinion, the fast propagation of the mafia culture that influenced the habits and practices of the paisas, the legitimacy of the bands by some locals and the normalization of their illegal practices in the people’s daily lives, are characteristics of the local culture (Salazar, 2002).

In conclusion, intra-urban displacement is a specific consequence of this particular internal conflict that affects the city and its population. It is deep-rooted in the location, in the particular culture, history and the outstanding inequality found in Medellin.

Scale:

The precipitating factors found by Ibañez and Vélez (2003) and Engel and Ibañez (2007) at a national level are similar to the particular drivers in the household decision-making in Medellin, due to local groups copying national opposition groups’ methods for controlling the territory, adapting them to urban areas. Nevertheless, the predisposing, proximate and mediate factors differ substantially from the findings of the previous pieces of research. Indeed, further research must be done in other urban areas of Colombia with intra-urban forced displacement in order to compare Medellin case’s drivers to those of other urban areas and determine whether they are only associated on a local scale.

Presumably, national drivers in Colombia differ from drivers of countries in different continents with internal forced displacement; it may only be possible to compare it with other Latin American countries with similar internal conflicts and problems, such as countries with gang wars and drug trafficking. Nonetheless, Colombia and Medellin seem to be very particular cases which cannot be generalized and are very difficult to study and understand.

Besides, the drivers clearly affected the poorer population in general, as individuals, families and collectives.

Duration or timeframe:

Information about the duration of the drivers could not be collected as this research was focused on one particular year, in this way is not possible to determine how the drivers may operate over different timescales.

Nevertheless, as mentioned in the proximate factors’ section, the year 2010 had very particular characteristics in the fluctuation of the internal conflict, the reorganization of the armed gangs and the variation in the strategy of territorial control. Those factors could have intensified the drivers, increasing the number of forced intra-urban displaced during that year.

Depth or tractability:

It becomes clear that the drivers found in Medellin in 2010 were deep-rooted in the local problems and culture. It would be possible to find fluctuations in the intra-forced displacement data, but the drivers are more embedded and intractable. As the Colombian internal conflict, drug trafficking, poverty and social inequality still create problems, the drivers would not change their tractability.

Evaluation of methodology

As the main source of information of this research was the testimonies of those already forced displaced, the findings lack comprehensive information about the pull factors which affect the migrants’ choices during the migration decision process. Additionally, this fact altered the model making it clear and easy to identify the push factors but leaving a gap regarding whether or not pull factors could have played a major role for Medellin’s internally displaced. A proximate study of the migration decision-making process could offer a better understanding of individual household decision-making and its close environment. In this respect, former research carried out in Colombia and its statistical model created for gathering this information was stronger than this one.

Further cross-case study research is needed in order to compare the findings in Medellin and determine if they can be generalized without falsifying hypotheses and results from a particular case that could be unique and therefore not comparable or extendable to other phenomenon of forced intra-urban displacement. On the other hand, the ‘drivers of migration’ model was well suited to the case of Medellin, as it helped create a comprehensive analysis of the context where the drivers were configured. As it is a very open and flexible model there was no need to adapt it to the specific circumstances of the case.

Only further research in Medellin can fully identify the ‘drivers’ complexes’ proposed by the model. It was beyond the scope of this research to study the duration and tractability of forced displacement in Medellin. As the background of the conflict was included in the literature review chapter, it was possible to give some information in these categories. However, the study of these classifications should be the scope of future research.

Conclusions

The ‘drivers of migration’ model is more comprehensive and flexible than its predecessors, it allows for a very broad analysis of the circumstances and the context within which people made the choice of whether or not to move. The combination of predisposing, proximate, precipitating and mediating factors or drivers shaped the circumstances and the environment within which the displaced made the choice to move.

The key drivers found are strongly connected to the internal conflict in Colombia, but they only respond to the specific dynamics of Medellin. Actually, the local armed groups, even if they work in a network connected to the structures of the guerrilla and the paramilitary, appear to have lost the militia or self-defence ideology that they had at the beginning, during their co-optation with the mafia cartel. Nowadays, their aim is almost exclusively to reap the profits of drug trafficking and other criminal enterprises.

Additionally, these drivers are linked to poverty, inequality, unemployment, integration clashes, and the mafia culture. Indeed, they are dependent on the particular history of the country and of the city, which in this case has been marked by violence. All of these factors play an important role when identifying the causes of the history of violence and therefore the causes of forced displacement.

As a result, the drivers almost exclusively affected the poor, as shown when comparing the quality of life indicators, the levels of unemployment and the geo-referenced map of forced displacement. Additionally, they affected women, young boys and male teenagers more strongly.

The main way in which gangs generated forced displacement was with death threats and homicides of family members or acquaintances of a household. In Medellin, the vast majority of migrants had very limited options. The percentage of preventive migration was minimal, in contrast to the cases of inter-urban displacement. But the decision-making process could be accelerated by the facilities of the city, such as wider access to information, a stronger or more consolidated social network and the possibility of getting shelter through humanitarian aid, or receiving economic aid in the place of origin.

In general terms, the two kinds of forced displacement (inter- and intra-urban) were the result of the illegal groups’ territorial strong holdings. Indeed, in Medellin, the precipitating factors were a manifestation of the way in which illegal bands express and conduct their territorial control or land strong holding. The main massive and individual forced displacements were generated in disputed zones; these zones were strategically the best-located neighbourhoods for drug transportation and posterior exportation.

Through an analysis of the causes of displacement it will be possible to implement the necessary public policies to prevent intra-urban forced migration. The times when gangs undergo structural rearrangements should be considered as a warning, a time to strengthen prevention strategies, as this is the worst point for generating forced migration on a large scale.

Government action should focus on attacking the identified deep-root causes and reconsidering the current strategy for stopping the level of murders as it could encourage the use of the forced displacement strategy instead. Also, it is very important to investigate the possible connivance between the police and some armed gangs, and it is necessary to disarticulate the criminal organisations and investigate their crimes. Decisively, the government’s recovery of its sovereignty throughout the territory is a must, especially in the peripheral areas of the city.

Prevention based on attending to particular cases of people in danger can temporarily reduce the levels of forced displacement, but only through solving the Medellin’s urban conflict itself can public policy stop forced migration. The peace agreement between the FARC-EP guerrilla and the Colombian government is helping to reduce forced displacement in rural areas. More has to be done in order to solve the deep roots of violence in Medellin, which nowadays is not fully connected to the internal armed conflict.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)