Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Papeles de población

versão On-line ISSN 2448-7147versão impressa ISSN 1405-7425

Pap. poblac vol.16 no.65 Toluca Jul./Set. 2010

The migratory flows in Spain: an analysis of the migration and immigration input from European Union

Flujos migratorios en España: análisis de los flujos de migración e inmigraciones de la Unión Europea

Jesús A. Valero–Matas*, Juan R. Coca** & Sergio Miranda–Castañeda*

* Universidad de Valladolid. E–mail: valeroma@soc.uva.es

** Universidad de Santiago de Compostela

Este artículo fue:

Recibido: 11 de agosto de 2010

Aprobado: 23 de agosto de 2010

Abstract

External migration has always been present in Spanish history. Few years ago Spanish people has migrated to Latin–Americans and Europe countries. Now, as Spain has ceased to be a sender of immigrants and has become a receiver of such, it may seem that emigration no longer exists at all. Reality tells us differently Also Spain. especially since 1986 (when it joined the European Union) has meant a large–scale transformation went from being a country of emigrants to a country of immigrants. In this article we show this process and the social consequences of this one.

Key words: Spain, emigrants, immigrants, labour.

Resumen

La migración externa siempre ha estado presente en la historia de España. Hace pocos años los españoles migraban a América Latina y a países Europeos. Ahora, cuando España ha dejado de ser emisor de inmigrantes y se ha convertido en receptor, puede parecer que la emigración no existe en absoluto. La realidad demuestra lo contrario; también España, en especial a partir de 1986 (cuando se incorpora a la Unión Europea) ha significado una transformación a gran escala, de ser un país de migrantes a un país de emigrantes. En este artículo mostramos este proceso y sus consecuencias sociales.

Palabras clave: España, emigrantes, inmigrantes, trabajo.

Introduction

The migration process is an essential part of human society. Since the beginning of humanity people have moved from one place to another. Yet external migration associated with the search for employment reached its highest point beginning in the 19th century approximately 42 Millions of persons (Carr–Saunders, 1936) and since then the levels have not stopped growing. These migrations have not always behaved in the same way, ñor have they had the same ebbs and flows. producing cycles with varying intensities.

If we carry out a chronological analysis on global migration, we must speak of four distinct periods. These are the second half of the 19th century, early 20th century, after the Second World War, and the late 20th century to today. Possibly, as Castles and Miller (2003) pointed out, the 21st century may well be the century with the highest levels of external migration. The previously stated periods of migration each behaved in a characteristic way, either due to the size of the group or to the sending and receiving countries.

The second half of the 19th century was marked by the departure of Europeans to the New World. This can be considered as the beginning of customary migration, especially directed toward the United States due to the need to develop a growing economic society, and with great expectations. Something similar occurred with Latin American countries, where Spaniards perceived a source of development that did not exist in Spain at the time. The late 19th and early 20th centuries led to an immigration explosion that possibly, until this moment, was the period with the highest volume of immigrants more or less about 60 millions (Davis, 1936). This flow of immigrants was marked by people from the old continent, including both industrialized and industrializing nations: the U.K., Ireland, Italy, Germany, Spain, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Russia, etc. The industrial revolution in the United Kingdom and other continental European countries began to make a dent in the production sector. Less manual labour led to the displacement of workers, which in turn led to unemployment and generated a large amount of surplus labour. Faced with this adverse environment and without future expectations, workers looked to America, where population pressure did not exist and industrial growth did. Canada, the United States, Argentina and Brazil would be a means of escape for citizens of the old continent, seeming to them a solution for Europe's problems. Undoubtedly, this led to a significant population transfer from Europe to America, substantially raising the population growth rate in the receiving countries.

After the Second World War, the situation in Europe, war–torn, with a decimated population who yet had great hopes of future prosperity, gave rise to a new shift of people within the old continent. Citizens of less–industrialized countries with deep social and labour issues would be the people who rebuilt old Europe. The new migratory wave would come from Mediterranean European countries and the north of Africa. Undoubtedly, the European war once again changed destiny as well as the migration model. No longer were people solely migrating to the New World; rather, they also came to old Europe, which was closer.

Finally, in the late 20th century, so–called globalization has caused a major migratory movement at a planetary level. The "advanced" countries were receiving large numbers of people fleeing poverty and seeking a better life. These migratory movements were composed not just of people with many transfers over long distances, but are also of significant regional movements, from Honduras to Mexico, from Peru to Chile, and so on. We can look at the flood of immigrants who have arrived in Spain since the early 90s, which still continues. However, the economic crisis and more restrictive immigration policies of the UE have reduced the amount of people who try to settle in Spain (Ilies, 2009).

Spanish emigration

External migration has always been present in Spanish history, so much so that it can be said that the Spanish people are born learning to emigrate. Since the reconquest of Spain, Spanish citizens have been marked by their population mobility. During the period of the reconquest, an important contingent of people emerged from the Cantabrian mountain range (called the "Foramontanos Route"), distributed themselves throughout Spain, and repopulated the reconquered land. (internal migration) Later, in the Middle Ages, another reason to migrate emerged. The discovery of America made it necessary to explore and establish colonies in the American territory. Once again, the people of Spain begin to migrate. The external mobility of Spaniards did have negative consequences, one of which was depopulation of the interior of the continent for new land in the new continent.

In the late 19th century, coinciding with the Spanish subsistence crisis, the first major wave of the Spanish population overseas occurred. A second large–scale flow would take place in the early 20th century. The economic recession of '29 and the Spanish Civil War slowed the wave of Spanish immigrants, however. The war forced many to flee their homes, especially in Republican Spain. These people would launch a diaspora due to persecution and fear of reprisal. Even so, migratory movements to the New World are still being triggered today, but with much less intensity with respect to previous eras. Emigration to Latin America practically stopped in the 1950s. World War II reversed the fate of Spanish emigrants. It wasn't necessary to go so far because our European neighbours needed labour. The migratory direction was now directed toward industrialized Europe. It wouldn't be until the early 60s to mid–70s when the largest contingent of Spaniards left for other parts of Europe, just over two million. The main cause of this migration process was the Stabilization Plan of Franco's government. The industrialization programs, the need to bring remittances from abroad, and field technologization caused thousands of people to seek a future outside our borders. Spanish industry could not absorb the surplus labour —there was a type of repulsion— yet existed an attractiveness about Europe.

The departure of the working–age population had a positive effect. About 10 percent of Spanish working–age left the country. What implied that a significant number of people will not press on the labour market, avoiding problems the state for its inability to absorb the workforce. And again, their wages sent a party to Spain, fattening and favouring the Spanish economy (Garmendia, 1981: 75).

Although in the 1960s migration to Latin American was reduced, many Spaniards still kept migrating to the former colonies. Work opportunities and language skills both helped. Mostly, they set out for Argentina and Venezuela. Between 1968 and 1975 Venezuela would be the final destination for almost 50% of Spanish immigrants (Palazón, 1998: 42).

The skilled labour needed by some Latin American countries made it so that skilled professionals, technicians, artisans, and industrial workers set out for America. Those initial immigrants often had disparate goals. In some cases, they thought they would only be there for a short period of time, just enough time to earn enough money and return to Spain. Others, however, looked to set down roots and to begin a new life. Time– and labour–related circumstances would frustrate such aims for many of them. Moreover, many of the immigrants began the adventure with their families in tow, thus substantially reducing the possibility of a return migration.

Spanish emigration to other parts of Europe involved a different sort of attitude. Most of this migration was based upon the need for peasant labour. European countries only wanted an active population, however, and in very few cases did they allow the worker to enter with his or her family too. This rule was in the restrictions imposed by the receiving countries who only wanted active labourers free from family burdens. Great Britain impeded workers with families from entering the country at all. Germany imposed serious obstacles to inactive labourers (i.e., the family). France was more permissive and allowed workers to move with their families in tow. For this reason, there is a higher migrant population in the country.

The occupations of Spanish workers were very different. In Germany, they performed their tasks in the iron, chemical, and textile industry. In England, they were directed more toward catering and domestic service. In Holland, they mainly worked in the metal industry, but some worked in the textile sector. In Switzerland, the bulk of workers were concentrated in construction and, to a lesser degree, the hospitality industry. In France and Belgium, however, they were all distributed equally in low–skilled sectors: industry, hospitality, construction, domestic service, and a small percentage in agriculture. As noted by Meseguer (1975: 412).

Spanish emigrants, on the other hand, always show at least minimal professional capacity, occupy a lower status within the European professional scale; most are employed in industry, not as skilled labourers, but as unskilled labourers or in jobs requiring few skills/a rapid learning curve.

Unlike those who immigrated to Latin America, those who immigrated to other parts of Europe had many difficulties trying to integrate themselves in the foreign cultures. Language ignorance was a barrier to full integration. Housing was another negative factor because low supply and high cost caused immigrants to look for cheaper places with poor conditions. Some companies and employers provided workers with accommodation, but it was generally in barrack–style housing meant for those who had come alone and not with their wives who also wished to work.

Discrimination at work was another unfavourable element for Spanish workers: they experienced wage gaps with native workers, lower wages, almost nonexistent relationships with local unions, and did not get the same benefits as the locals. Lack of formal preparation and difficulties with the language prevented them from being able to develop their labour skills as they natives did. Thus, due to their inability to compete for the higher positions, they occupied low–skilled positions. This pseudoislation was a catalyst for the creation of centres for Spanish workers, which were run by Spanish workers, and thus served as served as places for meetings and mutual support. They established links between workers and companies, and launched union activities and training.

The majority of Spanish emigrants, when they left their country, wanted to return someday. In fact, a migrant's need for a group of reference, while he or she is abroad, emphasizes his or her positive feelings toward his or her primary group and toward the local environment of his or her native country, reinforcing the desire to return (Cazorla–Gregory, 1998). Most immigrants did not establish social relations with the native population.

Their plan was generally based on working and saving, thinking of returning. Savings investments were handled differently by those immigrants who went to Latin America and the rest. The former used their savings to purchase land or small businesses, i.e., they were looking to the future. Meanwhile, immigrants in Europe or North America invested in housing, the education of their children, and business. Said ways of investing could be due to the societal perceptions of the host countries. In Latin America, like in Spain, owning land was something of great value; in Europe and in North America, housing, education, and business were becoming the main areas in which citizens invested. The Spanish immigrant, like any other, mimicked the behaviours of the host society.

Consequences of Spanish emigration

After the Spanish Civil War, the Spanish population grew very little. However, in the 60s, there was a dramatic rise in population —known as the Baby Boom— the population grew from 30 to 34 million people (Garmendia, 1981). The Stabilization Plan helped the migration process by reducing the wages of workers and increasing unemployment. Farm technologization displaced many farm workers to the city, looking for work, while others went abroad. One of the Plan's measures was to favour assisted emigration with the goal of receiving remittances from the emigrant, modernizing Spanish industry, and achieving full employment. This last goal was not achieved. However, emigration served to remedy the effects of unemployment and to calm the social situation in Spain.

There was no territorial immigration homogeneity. The largest contingents came from Galicia, the Canary Islands, Catalonia, Madrid, Asturias, and Castilla–Leon. With regards to the State's interest in receiving foreign moneys and the post–war modernization of Spain, the State was not subject to a policy of equal investments for every region and even less to a policy of equal investment in the provinces of origin of the emigrants. The provinces that most benefitted were those with lower populations. Therefore, the State missed the opportunity to distribute wealth and create homogenous territorial development. Provincial savings banks encouraged this inequality because emigrants mainly deposited their savings in said banks and, instead of spending these funds in provincial development, the banks invested in other, more developed regions because they were able to obtain greater benefits in those regions.

State policy to favour assisted emigration didn't follow a quality–based criterion, but a quantity–based one. The policy sent people to the countries with the highest labour demand, rather than more technologically advanced ones. Many of the workers weren't accepted because they didn't have the requested qualifications.

Spanish emigration today

As Spain has ceased to be a sender of immigrants and has become a receiver of such, it may seem that emigration no longer exists at all. Reality tells us differently. Spaniards continue to emigrate, but it is also true that their reasons are very different than they were in the past: travelling abroad to participate in the activities of Spanish businesses there, multinational contracts with foreign capital, research and international cooperation. Some are looking for job opportunities, while other look for a better–paying job or just a job in general. At present, there are about 1 471 691 Spaniards working outside of Spain's borders (INE, 2009).

The settlement of the Spanish people abroad has been very heterogeneous, as seen in the graphic. Latin America has the highest concentration of Spanish immigrants. But even within Latin America, the distribution is very unequal. Argentina and Venezuela are the two countries where the majority chooses to live, with 300 376 and 158 122 Spaniards, respectively, while only 993 Spanish citizens live in El Salvador. The United States of America holds 66 979 Spanish citizens while living 9 612 Spaniards in Canada. Focusing on the European Union, we see a similar picture: France, the United Kingdom, and Germany are where the majority of Spaniards are concentrated, and in the rest of Europe, Switzerland has the number, with 87 670 (INE, 2009).

Spanish economic growth in recent years and the current recession have led many Spaniards to return home. The completion of construction projects or commercial and profit activities have also contributed to their return. Many Spanish companies have economic interests in Latin America, the United States, and Europe and evidently this involves the movement of personnel to those countries. If we look at the figure 2, we see that the largest return was in 2004 and that in the years corresponding to the recession, the amount of returnees has been lower. This is possibly due to the high amount of Spanish unemployment, the highest in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE).

The current context: immigration in Spain

Immigration has changed the social, cultural, and ethnic map in Spain. Economic development in Spain, especially since 1986, when it joined the European Union, has meant a large–scale transformation. It went from being a country of emigrants to a country of immigrants. The transition to becoming a democracy began the process of economic and social movement. By then, foreigners who settled in Spain did not resemble the usual immigrants at that time, who immigrated for economic reasons, so they were called tourists. Social and climactic conditions contributed to their reasons for settling in Spain. These first few waves of foreigners share similar characteristics, being mainly retirees with high incomes. In fact, some parts of Mallorca, the Canary Islands, and Andalusia are mainly composed of foreigners who fit said profile.

Because for so many years immigration was not part of the Spanish social conscious, a myth has been formed that reduces immigrants to merely employment–related concerns—someone who is an immigrant must therefore be taking work from locals. Without a doubt, this stereotype, which extends from the 90s, has been a key part in the rejection of immigrants and immigration.

This type of thinking is present in the minds of many Spaniards, but it is well known that it has no basis in reality. As proven by Borjas (1993), native citizens benefit from immigration, mainly because immigrants provide complementary benefits for the production process. The benefits of immigrations will be greater the more immigrants' production differs from what the natives can produce by themselves. A second approach that dismantles this myth, it is the argumentation of Cachón (1997) that says that, in the advanced capitalist model, there is labour market segmentation, which leads to level differentiation. We speak of a two–tiered market. There is the first level characterized by high salaries, good labour conditions, promotions, etc. Then there is the second level characterized by low wages, poor work conditions, uncertainty, attrition, etc. In the first level, we find the natives and those foreigners from EU or developed countries, and in the second level those from outside the EU with middle– or low–level salaries. That is, those immigrants in the second level are recruited for the jobs that natives do not want, and serve as a "reserve army" for the junctures of the labour market. As indicated by Carlota Solé (2001: 32) there is some certain ethnics tratification in the Spanish labour market, wherein immigrants occupy the lower positions: domestic service, unskilled hospitality jobs, agriculture, construction labourers and retail, which are all jobs mostly shunned by native workers.

This shows no relation between immigration and local unemployment, as it was intended to do. Distrust creates a degree of uncertainty within the immigrant population and rejection among the natives.

Following this line of analysis, it should be indicated that as a result of the aging Spanish population and the structural changes in Spanish society, immigration is solving two problems: a) some of the economic and labour problems, filling jobs rejected by natives and contributing to the pension plans1, b) to a lesser extent, they have helped to repopulate some areas where depopulation was occurring as well as increase birth rates, as Spain has one of the lowest birth rates in Europe.

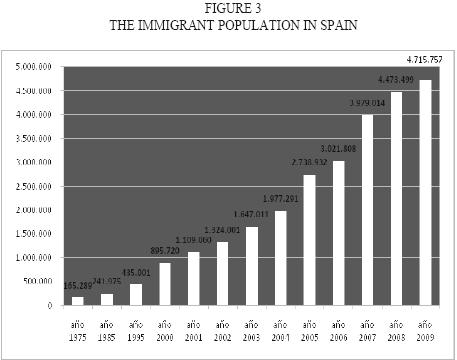

In the study of Spanish immigration, we must discuss two issues, a) different immigrant arrival periods, whether for political reasons or Spanish economic growth, and b) the size of the immigrant contingents, which does not show a homogeneity in the migration process. With regards to the first issue, there were various periods. The first, which we can cali the beginning (1975–1985), includes the first arrivals of immigrants, but Spain did not act as a receiving country during that period. In 1975, only 165 289 foreigners lived in Spain, and by 1985 that number had only increased to 241 975. Most of them were based either in Madrid or Barcelona. The second, or growth (1985–1995), phase was when Spain began to be seen as an immigrant–receiving country, since the number of arriving immigrants had doubled. Thus, the immigrant population went from 241 975 to 499 773. The third, or acceleration (1995–2007), period saw a huge increase in the number of foreigners, outstripping all prior expectations. From the 499 773 immigrants of the previous decade, the number rose to 3 979 014, which represented 8.5 per cent of the total population (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2008). At this time immigrants began to move to other geographical areas, due to the high concentration in large cities and the production needs of other Spanish regions. The autonomous regions, such as Murcia, Valencia, the Canary Islands, Andalusia, and, to a lesser extent, Navarra, Galicia, or Castilla–Leon were all subject to a significant cultural transformation. The fourth, or maturity, period (2006–2009) saw the continued arrival of foreigners, but in much smaller numbers, due partly to the world financial crisis and the restrictive political policies of the European Union. Immigrants even began to talk about a return to their home countries, but such talk did not seem to be carried out. Instead, they began a process of internal mobility, looking for areas with a low immigrant presence.

We now must address the second criterion, the size of the contingents. According to Reques–Cos (2003), we speak of the European period because until 1990 most of the foreigners living in Spain were citizens of the EEC, now called the EU. From that year on, the Latin American explosion began, which to this day has been the largest contingent of foreign residents in Spain. Note that the arrival of Latin Americans followed a saw tooth evolution pattern. Initially, the first among them to move to Spain in the 70s did so for political reasons, and thus came from countries under dictatorships, like Cuba, Chile, Uruguay and Argentina. Until the mid–90s, Argentineans made up the most numerous group with 20 000 immigrants. In the mid–90s, a change occurred. Dominicans and Peruvians displaced the rest of Latin Americans, becoming, in the year 2000, the most numerous groups, mainly because women from these countries were arriving to work in domestic service.

Now, new migratory movements are emerging from other Latin American countries. This time, it will be the Ecuadorians and Colombians who, in 2008, will become the most numerous groups, with 421 527 and 274 832 people, respectively. In the nineties, a period of immigration explosion in Spain, Africans entered the scene with a bang, and in 2008 they became the second largest group of immigrants after the Latin Americans. Moroccans represent three–quarters of Africans living in Spain (717 416 persons in 2008 of a total 922 635 African immigrants), followed distantly by Algerians and the Senegalese with 48 919 and 34 013 (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2009). Until the 90s, the presence of foreign Africans was basically insignificant. Once the 90s began, Africans' entrance into Spain was unceasing. The causes are multiple. In our view, three elements come together: 1) the difficulty of finding employment in France, a preferred destination for Moroccans, Algerians, and Tunisians, 2) the Spanish economic boom, and 3) the solidification of social support networks for immigrants. The labour niches occupied by these people were mainly in the agricultural and construction sectors.

In 2003, an important migratory movement began, originating in Eastern Europe. The countries of origins were varied. Romania sent the most. Domestic problems, low levels of industrialization, and the lack of prospects were all issues that caused many to leave, seeking work and better living conditions. Between 2003 and 2006, the transfer of humans from Romania to Spain was unceasing, doubling in just one year.

With the EU's expansion (2007), involving the integration of Romania and Bulgaria, the number of immigrants arriving per year went from 211 325 in 2006 to 603 889 in 2008. Something similar happened with Bulgarian citizens as well, but not to the same degree as with Romanians (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2009).

Asians make up the fourth continental group. Ever since the Spanish economic boom, they have been present in our human geography. In the 80s, Philippine natives established the diaspora, with women who came to work in domestic service making up a large part. In the late 20th century, China amended its immigration policy and embarked upon a new policy by encouraging and even urging its citizens to leave the country and send money back home. Spain would be one of their destinations, and in 2005 it would become the largest Asian group. Pakistanis also became a major presence, and since 2002 have been the second largest Asian group, forcing the Filipinos to third place.

Finally, we address the contingents from Oceania and North America. Residents in Spain from these countries are not very numerous, and these citizens are generally highly skilled and work with large companies. There are barely 18,000 Americans, 1 500 Australians, about 2000 Canadians, and about 500 New Zealanders (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2009).

Another issue that should be highlighted is the economic profiles of immigrants who have arrived in Spain during the last 20 years. In the 70s and 80s, most foreigners were characterized by their high education levels. That is, around 70 per cent were college educated or vocationally trained. By the 90s, the typical immigrant's profile was markedly different; there were usually people with a primary– or secondary–level education, and a low percentage of people with higher education. In addition, illiterate people started to arrive. This fact allows for two interpretations: on one hand, it justifies the ethnic stratification of the labour market because immigration allows immigrants to fill jobs tailored to their profiles. On the other hand, their professional limitations relegated them to precarious, low–skilled jobs.

Moreover, the geographical distribution of immigration in Spain is very varied, with three–quarters in five autonomous regions: Catalonia, Madrid, Valencia, Andalusia, and the Canary Islands. Certainly, there are immigrants in all of Spain's autonomous regions. Social networks almost end up concentrating their people in specific areas. Most Latin American immigrants are located in Madrid, Catalonia, Valencia, Andalusia, and Murcia. For example, the largest group of Peruvians and Dominicans live in Madrid and Barcelona because their main work activities are channelled toward domestic service and hospitality. Ecuadorians are also located in the two big Spanish cities, but there exists a greater diversification, with two large colonies devoted to horticulture in Murcia and Andalusia. In the case of the immigrants from Eastern Europe, the largest number resides in three provinces: Madrid, Zaragoza, and Castellon, whose main labor activities are construction, industry, and agriculture, despite the fact that many of them have been educated in a university. As Viruela points out (2002: 14), between the Romanian citizens living in Castellon, there is a high proportion of people with professional occupations (economists, lawyers, engineers, doctors, nurses, teachers...). The Ukrainian contingent is located mostly in Madrid, Barcelona, and Alicante, and is devoted to activities related to hospitality, construction, and other service–related occupations. Moroccan immigrants reside in Barcelona, Madrid, and Murcia, and provide their labour in farm– and construction–related work. In contrast, Algerians, who work in similar areas, have gone to cities such as Alicante, Valencia, and Zaragoza. Finally, Asians, with the Chinese making up the largest group, can be found in Barcelona, Madrid, and Valencia, with their labour activity concentrated in retail trade (the businesses known as "Everything for 100") and Chinese restaurants. The mainly female Filipino group's main activity is in domestic service, focusing on Madrid, Barcelona and the Balearic Islands.

While most immigrants are concentrated in five autonomous regions, they are not those who have the greatest impact on the workforce. If we look at the above chart, we can see that it is the Balearic Islands where the immigrant population has the highest participation rate in work activity (22.9 per cent), followed by Murcia with 21.4 per cent (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2009). This indicates that, when studying immigration, one must look not only at the concentration of immigrants but also the relational indices of native– and foreign–born populations. Both the Balearic Islands and Murcia are single–province autonomous regions, but both have high concentrations of immigrants. Therefore, their impact on the labour market is greater, as well as their impact on social and integration problems and costs in education, health, and social services. If we add it up, the economic crisis amplifies unemployment spending in both immigrant and native populations, and at the same time it produces such inequalities and could even cause rejection of immigrants.

The immigration in Spain represents 11.5 per cent of the total Spanish population, a number that it places to Spain in the second country with major population of foreigners of the EU behind Germany. (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2009). However, social and cultural changes have happened so fast that Spanish society has not been able to properly assimilate, especially with the emergence of very diverse cultural groups. Spanish society has been overwhelmed in a very short length of time, due to the presence of people with diverse cultural values. There being no acclimation process, problems were created. The big picture reveals certain socio–cultural differences, especially as compared to Muslims of Arabic origin. With this group, there are more integration problems due to their eagerness to educate their children about their original cultural values. Conflicts with the Black Muslim population are somewhat less clear. In our judgment, these conflicts are due to historical issues because, while black African Muslims have embraced Islam in recent times, for Arab Muslims, Islam is inherent to their culture. They are also less likely to accept any social change in their children. Young people are open to it when they come into contact with other lifestyles that are contrary to their original traditions. This openness is seen by their parents as an outright rejection of their native culture and an abandonment of their religion, thus causing socio–family conflict.

Lastly, we cannot forget about the almost one million so–called "illegal'' immigrants who live in Spain (Compiled from data from the Department for Work and immigration and National Statistic Institute). So far we have looked at data about people with residence permits, but we cannot ignore those who live in Spain without permission. If the circumstances of the administratively regulated immigrants are complicated, it is much more so for those who do not have legal permission to live in Spain. Without work permission, the immigrant cannot work and hence is often exploited by businesses and involved in criminal activities. This irregularity favours exploitation at the hands of employers who take advantage of the situation by paying lower salaries for the same work, distorting and breaking down the labour market, and increasing illicit work. It also contributes to the recruitment of such persons by organized criminal groups.

The current economic crisis has had a higher impact in the immigrant community—in some regions of Spain, the unemployment rates of immigrants have exceeded 50% (Statistical Yearbook of immigration, 2009)

Education is another important cultural aspect. The arrival of people with cultural differences has led to a substantial change in our schools. This is an enriching experience with regards to our children because they are being educated amongst great cultural diversity. Yet the education of children and adults opens major questions about the future of education, questions that may lead to various national and regional changes, and will continue to be some of the great unknowns of our educational system.

So far, for many reasons, whether due to not knowing the language, lack of life plans, relative economic deprivation, strong cultural differences, and in my cases lower cultural levels, immigrants perform more poorly than natives in academic settings. It is true that the amount of time spent in Spain and the age upon entry are both key factors for academic performance and social integration. Immigrant children who have been in Spain for over five years and who came to Spain when they were ten years old or less have a very favourable socialization outlook. Thus, they also have a favourable outlook with regards to their integration in the Spanish socio–educational model. In other words, their performances are similar to native children.

On the other hand, the ghettoization of schools is having a counterproductive effect on the goal of a culturally pluralistic coexistence. Most immigrants live in areas with at least some degree of decline (Valero, 2007), which implies a high immigrant concentration in said area.

When the school has a high level of immigrant students, many natives move their children to schools where there are no immigrants or their number is relatively low, and thus certain schools begin to exist solely for immigrants or excluded groups. Such behaviour is hardly conducive to integration and coexistence —there is no cultural contact.

Housing is another important factor in inclusion as well as the achievement of the immigrants' life plans. Their dwelling becomes a means to integration, as it is a way of accessing various social benefits, improving their standing, and reducing their vulnerability (Valero 2007). When immigrants try to live in outlying areas, suburbs, or city centres, they are often stigmatized and seen as contributing to the decline of the neighbourhood. Actually, what happens is that immigrants live in these areas because they have insufficient means to live anywhere else with better conditions. We're talking about urban areas where houses have major structural deficiencies that violate the minimum health regulations. In other situations, high housing costs lead them to live in overcrowded apartments because, with their meagre wages, they cannot afford to own a home or rent a property. It also happens that many landlords refuse to rent to immigrants. Both of these causes are leading to abuse and exploitation of immigrants' difficulties with regards to finding housing, which in turn increases the phenomenon of so–called hot beds. In many cases, this abuse is carried out by the immigrants themselves, the ones who have managed to rent apartments. They profit from others' unstable situations.

A global vision: reflexions about immigration

The arrival of workers from countries with low– or medium–incomes has not only led to the creation of new employment niches, but also to the displacement of native workers. On the other hand, thanks to immigrant workers, native workers have been promoted because of the foreign labourers filling the jobs of lower statuses.

The immigrant labour ethnic stratification is plainly evident because there are labour niches which only exist because of immigration. We have created new employment areas, some of which have been filled by native workers and others of which were created solely for immigrants. Economic immigration has produced a structural change in the labour market. Many companies require more skilled labour, but in turn outsource more services to other companies, resulting in a decline of labour quality. Two things have helped accelerate this deterioration: one, the pressure on immigrants to find a job causes the native workers to perform the same tasks for lower pay. Two, companies recruit unskilled employees who are paid less, essentially taking advantage of immigration.

As suggested by Iglesias and Llorente (2008: 90), to date, immigration processes have had a positive effect on our economy in terms of the general welfare. Nonetheless, immigration is causing regional labour disputes. Immigrants tend to settle in areas with active labour markets; at the same time, they put pressure on the market and contribute to the revitalization. Thus, they contribute to improve levels of labour activity. The less dynamic regions are not affected by immigration pressures and they do not blame immigration when they are unable to find work. As a consequence, there are significant inequalities between the autonomous regions. This had been occurring up until 2008, but as a result of the economic crisis, other problems have emerged, such as increased unemployment in the immigrant population, forcing them to seek employment in an autonomous region with lower immigrant presences.

An important component in the economic analysis of immigration lies in remittances. The sending of money to their families is often one of the main reasons that they began the migration process. Remittances are essential for their home country's development, a way to improve their families' living situations, and a means to return home again someday. Remittances are often meant to be used to buy a house, to buy land, or to open a business. Nonetheless, many remittances are not used in the intended way and are instead used to buy televisions, cars, washers, video game consoles, etc. In 2009, the Latin–American Development Bank stated that the average amount of money sent by immigrants was 3000 Euros, and in total some 69,200 million Euros had been sent to Latin America, which was the largest source of development for many Latin American countries. Something similar happened with African immigrants. Yet these huge amounts of money are not having an effect on the economic labour structure of the country. Many microbusinesses that are created after the immigrant returns have high levels of failure. The so–called children of immigration, who live with grandparents or uncles and aunts, are being brought with excess consumption. While their relatives are working overseas, the recipients of such remittances do not invest in the future and often squander the money sent by their overseas relatives. This has begun to create serious and profound family problems. The lack of investment forces the overseas relative to delay his or her return. In many cases, because he or she does not return, he or she begins to build a new family in the new country, abandoning the original.

Though, unlike the economic contributions of the Spanish immigrants of the past, with regard to the Latin–American immigrants in Spain, a substantial difference appears, possibly for the contextúa! difference. In the past an exposition of life based on the attainment of aims planed on the creation of future business plans. In the present, as happens in Latín America lies in the consumer. Here it takes root in one of the differential aspects between the remittances of the Spanish immigrants of the past with the Latin–American immigrants.

The global economic crisis is reducing migration flows, but is especially frustrating the expectations of many immigrants to American and European dreams. In the Spanish case, although immigrants continue to arrive, the percentages are much lower than years past. But also, many are returning to their countries of origin by the lack of work. And others do not return for fear of failure. This fact leads to a deterioration of immigration in the host country. Maybe this is one of the evils of the XXI century immigration.

Bibliography

BORJAS, G, 1993, Friends of strangers, the impact of immigrants on the USeco–nomy, Basic Books, Washington. [ Links ]

CARR–SAUNDERS, A, M, 1936, World population, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

CASTLES S and M. MILLER, 2003, The Age of Migration, The Guilford Press, New York. [ Links ]

CACHÓN, L, 1997, 'Segregación sectorial de los inmigrantes en el Mercado de trabajo en España', en Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, núm. 10. [ Links ]

CAZORLA, J, and D. GREGORY, 1998, 'La emigración española a países Europeos: problemática y soluciones', en Revista andaluza de inmigración, núm. 25. [ Links ]

DAVIS, M, R, 1936, World migration, MacMillan, New York. [ Links ]

GARMENDIA, J, A, 1981, La emigración española en la encrucijada, CIS, Madrid. [ Links ]

IGLESIAS, C. y R. LLORENTE, 2008, "Efectos de la inmigración en el mercado de trabajo español", en Papeles de Economía, núm. 367. [ Links ]

ILIES, M, 2009, "La política de la Comunidad Europea sobre inmigración irregular: medidas para combatir la inmigración irregular en todas sus fases", en Documentos de Trabajo ( Real Instituto Elcano de Estudios Internacionales y Estratégicos), num. 38. [ Links ]

MESEGUER, J, 1975, "La emigración española en los países de la CEE", en Revista de Instituciones Europeas, núm. 2. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE TRABAJO E INMIGRACIÓN, 2009, Anuario de inmigración, Publicaciones del Ministerio de Trabajo, Madrid. [ Links ]

PALAZÓN, Ferrando, S, 1998, Reanudación apogeo y crisis de la emigración exterior española (1946–1995), Eria. [ Links ]

REQUES, P. y O de COS, 2003, "La emigración olvidada: la diáspora española en la actualidad", en Papeles de Geografia, núm. 37. [ Links ]

SOLÉ, C. y S. PARELLA, 2001, "La inserción de los inmigrantes en el mercado de trabajo, el caso español", en C. SOLÉ, El impacto de la inmigración en la economía y en la sociedad receptora, Anthropos, Barcelona. [ Links ]

VALERO MATAS, J. A., 2007, La educación social ante los nuevos retos de la inmigración y los servicios sociales, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid. [ Links ]

VIRUELA MARTÍNEZ, R, 2002, "La nueva corriente inmigratoria de Europa del Este", en Cuadernos de Geografía, núm. 72. [ Links ]

1 It is true that immigration not recorded by the Administration is causing serious problems to the different administrations due to the increase of health and education spending.

Información sobre los autores:

Jesús Alberto Valero–Matas. Doctor in Sociology (UCM). Graduate in sociology (UCM) and BA in Political Science and Management (UCM). He is currently professor of sociology at the University of Valladolid. He has been visiting professor at various universities abroad, Edinburgh University, Auckland University, Colorado School of Mines, UNAM, Polish Academic Nauk, Georgetown University, etc. She has won more than 20 publications in national and international journals and several books.

Juan R. Coca. Biology graduate, Master in Logic and Philosophy of Science, and currently a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Santiago de Compostela. He is a researcher in the department of sociology on sociological imagination at the same university. He has published over 40 papers and a dozen books chapters. He has been visiting researcher at the University of Valladolid.

Sergio Miranda–Castañeda. Holds a diploma in Social Work for the University of Valladolid (2002) and BA in Sociology for the University of Salamanca (2006). Currently working as a graduate research at the Office of Research and Evaluation at the University of Valladolid and associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Work at the same university.