Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Papeles de población

versión On-line ISSN 2448-7147versión impresa ISSN 1405-7425

Pap. poblac vol.12 no.47 Toluca ene./mar. 2006

Integration from below: Mexicans and other Latinos in the US labor market*

Integración desde abajo: mexicanos y otros latinos en el mercado laboral de Estados Unidos

Elaine Levine

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Abstract

In this article I shall analyze what I consider to be a certain degree of de facto labor market integration between Mexico and the US, which was further accentuated by Nafta, under conditions that are mostly disadvantageous for Mexican migrant workers, in terms of the US context. In the first part of the article I shall briefly analyze labor market conditions in Mexico to explain why low-waged jobs in the US are so attractive to Mexican migrants. I shall then proceed to analyze labor market outcomes for Mexicans and other recent Latino immigrants to the US. I will also look at the relative socioeconomic status of different groups of Latinos and compare their educational attainment, occupational profiles and incomes with those of the non-Hispanic population in the US.

Key words: international migration, Latin American migrants, labor market, Mexico, United States.

Resumen

En este artículo analizaré lo que me parece ser un cierto grado de integración de facto entre los mercados laborales de México y Estados Unidos, que fue acentuado aún más bajo el TLCAN, y donde existen condiciones desventajosas para los trabajadores migrantes mexicanos, en términos del contexto estadunidense. En la primera parte del artículo analizo las condiciones que prevalecen en el mercado laboral mexicano para explicar por qué empleos de bajos salarios en Estados Unidos resultan tan atractivos para los migrantes mexicanos. Después analizaré el desempeño de los mexicanos y otros latinos recién llegados en el mercado laboral estadunidense. También examinaré el estatus socioeconómico relativo de los diferentes grupos de latinos, comparando su escolaridad, su perfil ocupacional y sus ingresos con los de la población no hispana en Estados Unidos.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, migrantes latinoamericanos, mercado de trabajo, México, Estados Unidos.

Since the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, the United States has consistently opposed any further facilitation of freer transit and more permanence for workers from Mexico in spite of the evident demand for such labor. Nevertheless, Mexican immigration has continued to grow over the past two decades. The once circulatory patterns, of going and coming between the US and Mexico on a regular basis, have given way to more permanent settlement for many. The Current Population Survey estimate for 2004 of 10.6 million Mexican born residing in the US represents more than a thirteen fold increase over the 1970 census figure. Decennial averages have increased from 122 thousand migrants per year in the seventies to 450 thousand per year since 2000. Undocumented migration continues in the post IRCA period at unprecedented levels. According to Pew Hispanic Center calculations, approximately half of all Mexicans in the US and from 80 to 85 per cent of the more recently arrived are unauthorized (Passel, 2005, 36-37). It also seems that most of them had some sort of employment in Mexico before migrating (Kochhar, 2005: 1). The debates currently underway in the US Congress may eventually yield some sort of guest worker program and possible regularization for millions of undocumented Mexicans now living and working in the US. Such programs, however, will inevitably fall short of eliminating the persistent supply of and continuing demand for low wage migrant workers.

One of the main arguments invoked, on both sides of the (US-Mexico) border, when promoting NAFTA was that it would help stem Mexican migration to the United States. This, along with other false expectations that were generated to sell the idea of a tri lateral trade agreement, is belied by the realities of the past twelve years. Contrary to those a priori expectations, deteriorating employment conditions in México have coincided with a continuing demand for cheap Latino labor in the US, thus bolstering the migratory process. On the Mexican side of the border there seemed to be some sort of subliminal dissemination of the idea —even though there were no official statements or declarations to that effect —that Mexico would somehow benefit from a trade agreement with its more prosperous partners in the same way that Spain, Greece and Portugal have benefited from membership in the European Union.

On the US side, however, it was constantly and explicitly reiterated that NAFTA was conceived as a trade liberalizing agreement and nothing more. Nevertheless the idea that eliminating existing barriers would increase trade among all three partners, and thus increase the demand for each others' exports which would in turn create new export related jobs in each country, was actively espoused by promoters of the agreement. While some sectors expressed concerns about the possibilities ofjob losses, such preoccupations were played down in official rhetoric and discourse. Indeed, a major selling point in the US was not only that new jobs would result but also that there wouldn't be so many Mexican immigrants competing for jobs north of the border anymore.

President Clinton underscored this point during an October 1993 town hall meeting in Sacramento, 'One of the reasons that I so strongly support this North American Free Trade Agreement is, if you have more jobs on both sides of the border and incomes go up in Mexico, that will dramatically reduce the pressure felt by Mexican working people to come here for jobs. Most immigrants come here illegally not for the social services, most come here for the jobs 4 (Clinton, 1993: 185).

Mexican President Carlos Salinas, on a visit to the US prior to the signing of NAFTA, warned audiences that if the agreement wasn't signed an avalanche of Mexicans would be forced to emigrate to the north. "Only NAFTA, he assured his listeners, could create the jobs and raise the wages in Mexico that would thereby alleviate migratory pressures" (Bacon, 2004: 253-254). Or framing this idea in more positive terms he often insisted both at home and abroad that NAFTA would allow Mexico "to export goods and not people". As Manning and Butera have argued, the free trade doctrine invoked to gain acceptance for NAFTA implicitly assumed that as a result the Mexican economy would be modernized, which would in turn "increase jobs, raise wages, reduce consumer prices, elevate the Mexican standard of living and reduce future flows of illegal immigration to the United States" (Manning and Butera, 2000: 185).

Generalized modernization of production units, higher employment levels, higher wages, lower prices for consumers and increased living standards which would, in turn, reduce the flows of undocumented migrants from Mexico to the US, is a tall order indeed for a free trade agreement. Certainly too many expectations were pinned on a partnership of this nature. Conversely, most of Mexico's economic ills cannot, and should not, be attributed directly to NAFTA. At the same time it seems reasonable to have hoped, at least, for more results on the positive rather than on the negative side of the balance. It seems clear that up to this point in time the net impact of the agreement, in combination with other endemic factors, has been devastating for Mexico's labor market. Thus it can be safely affirmed that migratory pressures have increased over the past twelve years rather than waning.

In this paper I will analyze what I consider to be a certain degree of de facto labor market integration, further accentuated by NAFTA, under conditions that are mostly disadvantageous for Mexican migrant workers. In the first part of this paper I will briefly analyze labor market conditions in Mexico —characterized by declining real wages, insufficient job creation to absorb the increasing labor supply, and marked expansion of the informal labor market— to explain why low wage jobs in the US are so attractive for Mexican migrants, both male and female. I will then proceed to examine the labor market outcomes for Mexican workers in the US, in terms of occupations, and earnings. I will analyze the socioeconomic status of Mexican origin Latinos over the past decade or more to underline the increasing earnings differentials that emerge between Latinos and others, and those persisting between Latino men and women. Given the increasing segmentation and stratification of the US labor market it is likely that upward mobility will prove to be more difficult for most recently arriving Mexican immigrants and their children than it was for previous cohorts of Mexicans and other groups of immigrants throughout most of the twentieth century. Furthermore, Mexican women migrants who join the US labor force experience the double negative impact ofboth gender and ethnic discrimination.

Declining real wages and pervasive informality in the Mexican labor market

Undeniably Mexico's current economic ills cannot be attributed to solely to NAFTA, nor to globalization, in and of itself, without taking into account the pervasive corruption at all levels and the self serving economic policies implemented by the dominant elites throughout most of the country's history. However, since Mexico's economic woes began to intensify in the early 1970s, successive governments have been trying to find easy solutions to problems that require more radical changes, which would affect vested interests and alter the status quo in many respects. It was hoped that NAFTA would help Mexico find new trading partners and interested investors from other regions because of the country's thus enhanced relationship with the US market. Instead it seems to have merely intensified Mexico's connections with and growing subordination to the US economy.

Mexico's highly protective import substitution model —which allowed for thirty years of generally favorable macroeconomic performance— began to falter in the 1970s. President Lopez Portillo's hopes that oil resources would provide a quick fix were dashed by mismanagement, corruption and adverse external conditions. The oil boom in the second half of the 1970s postponed the impending crisis for a few years but rapidly led the country into unsustainable over indebtedness. When oil prices fell to more normal levels at the beginning of the 1980s, reducing the flows of foreign exchange, Mexico was on the verge of defaulting on its international loans. Payment schedules were renegotiated and the economic adjustment programs initiated marked an abrupt change of course in terms of economic policy. The country abandoned its import substitution/interventionist state model in favor of market liberalization and privatization policies aimed at achieving export oriented industrialization which has by and large proven thus far to be an unattainable mirage.

For Mexico, as was the case for many other Latin American countries, the 1980s proved to be a lost decade in terms of economic growth and the well being of most of the country's inhabitants. Between 1980 and 1988 GDP growth only averaged out to 1.1 per cent per year (Salas, 2003: 39). which means that GDP per capita declined significantly. The subsequent improvement registered during the Salinas administration rested on very weak foundations -including volatile flows of foreign capital attracted by high interest rates and manipulation of the exchange rate- as was abruptly evidenced by the peso crisis at the end of 1994. Since his own credibility was at stake along with Mexico's and NAFTA's, President Clinton responded immediately and used discretionary funds to help bail out the newly affiliated, and now discredited, trading partner.

After a severe drop in GDP growth in 1995, by —6.2 per cent, the Mexican economy grew at an average rate ofjust under 5.5 per cent for the next five years (Cuarto Informe de Gobierno, 2004, 177). In 2001 real GDP was stagnant (registering a 0.0 per cent growth rate) and growth since then has been sluggish (0.7 per cent in 2002, 1.3 per cent in 2003) with preliminary figures showing some improvement in 2004 (3.8 per cent) (Cuarto Informe de Gobierno, 2004, 177). However only the top ten percent of all households saw any rise in their share of national income, as a result of those favorable GDP growth rates, while the remaining 90 per cent either suffered a loss of income share or experienced no change (Polaski, 2004, 17). Furthermore, the improvement registered in the second half of the 1990s and the subsequent slump as of2001, seem to indicate that Mexico's macroeconomic performance now depends more heavily on the US business cycle than before. The recession in the US immediately showed up as a decline in Mexico's merchandise exports and imports, foreign investment levels, employment levels, and GDP growth rates.

One of the arguments invoked against NAFTA was precisely the fact that Mexico would become even more dependent on trade with its number one partner the US. Supporters had insisted that inclusion in a North American trading block would make Mexico a more desirable trading partner for countries outside of the region as well. Mexico now imports more merchandise from Asia than before (approximately 18 per cent of total imports) while the US currently purchases almost 90 per cent of Mexico's exports. Foreign trade (imports plus exports) increased from approximately 30 per cent of GDP in the pre NAFTA period to over 50 per cent in the post NAFTA years leaving the Mexican economy all the more vulnerable to macroeconomic fluctuations in the US.

Rather than moving towards a more diversified and better integrated industrial sector with greater forward and backward linkages, Mexican industry has become even less integrated domestically and more dependent on imported inputs and technology. The maquiladora sector, which has grown significantly, typically imports 97 per cent of the value of its final output and only three per cent of the final value of these goods, which are subsequently exported, is produced in Mexico. A most disturbing fact is that the non-maquiladora export sector is increasingly behaving in a similar fashion. As Sandra Polaski points out,

The intra-firm production carried out by multinational firms operating in Mexico in sectors such as the auto and electronics industries depends heavily on imported inputs. It seems probable that Mexican manufacturers that previously supplied inputs to large manufacturing firms have lost a significant share of input production to foreign suppliers... (Polaski, 2004: 7-8).

Maquiladora output and employment increased significantly between 1994 and 2001 and has fallen off somewhat since then. Meanwhile employment in non maquiladora manufacturing was just beginning to recuperate from the peso crisis decline in the mid 1990s, when the 2001 recession provoked new job losses. Thus non maquiladora manufacturing employment was lower in 2004 than in 1994, with a net loss of about 160 000 jobs. In spite of the fact that over 200 000 maquiladorajobs were lost between 2001 and 2003, current employment is considerably higher, by approximately 529 000, than it was in 1994. Because of the substantial increase in maquiladora employment which now represents close to half of total manufacturing employment (maquiladora plus non maquiladora manufacturing), as compared to less than 30 per cent before NAFTA, the sector as a whole showed a net gain in employment over the past decade, of approximately 387 000 jobs between 1994 and 2004 (Romero and Puyana, 2004: 97-102; and Polaski, 2004: 4-11).

However this most modest job growth in manufacturing was not nearly enough to offset the decline that took place, over the same period, in agricultural and agriculture related employment. According to Romero and Puyana the net job loss in agriculture was approximately 700 thousand, from 6.9 million prior to NAFTA to 6.2 million in 2001 (Romero and Puyana, 2004: 97). Polaski maintains that "Agricultural employment in Mexico actually increased somewhat in the late 1980s and early 1990s employing 8.1 million Mexicans at the end of 1993,just before NAFTA came into force. Employment in the sector then began a downward trend, with 6.8 million employed at the end of 2002, a loss of 1.3 million jobs"(Polaski, 2004: 9). Even given their more modest estimations of job losses, Romero and Puyana conclude that growth in the production of agricultural export crops was by no means sufficient to absorb those displaced from non export agriculture who were thus forced to seek employment elsewhere. Limited growth in manufacturing employment indicates that not many of them were able to find jobs there either. Most were eventually employed in low paying service and construction jobs offering no legal benefits and protections or worked in the informal economy, and the rest migrated to the US (Romero and Puyana, 2004: 98-100).

Zarsky and Gallager estimate that 6.5 million Mexicans entered the labor force between 1994 and 2002, while only 4.4 million new jobs were created, leaving over two million unemployed to seek work in larger cities or across the border (Zarsky et al., 2004: 3). Polaski maintains that Mexico needed almost a million jobs a year to absorb growth in the labor supply from 1993 to 2002 (Polaski, 2004: 3). My own calculations based on data from the Cuarto Informe de Gobierno (the President's Fourth Annual Report) show that the economically active population grew from 33.7 million in 1993 to 43.4 million in 2004, an increase of 9.7 million. At the same time only 2.7 million new jobs were created in the formal economy. Thus the ranks of the unemployed, under employed or informally employed have risen by at least seven million since NAFTA began. If we consider the fact that a significant number of those in the working age population (all persons twelve and older) counted as economically inactive —which rose by 7.4 million over the same period— would be looking for a job if they had expectations of finding one, the employment deficit accumulated over just the past ten years is even larger, probably similar to Polaski's one million a year deficit.1

The official "open unemployment" rate of 3.7 per cent for 2004, which is about 1.6 million persons, grossly understates Mexico's job deficit in a blatant attempt to cover up the fact that half or more of those who are counted as employed actually work in the informal economy. According to Polaski, informal employment rose throughout most of the 1990s approaching 50 per cent of the total in 1995 and 1996 "following the peso crisis and the subsequent economic contraction. After economic growth resumed in the late 1990s the informal sector shrank somewhat, but still accounts for about 46 percent of Mexican jobs" (Polaski, 2004: 12). An International Labor Organization (ILO) report released in 2004 maintains that informal sector employment in Mexico has increased from 55 to 62 per cent of total employment over the past few years (Martinez, 2004: 33). In the spring of2005 President Fox celebrated the fact that jobs registered by the IMSS in February had reached a historical high for that time of the year of12 million 585 thousand (Fernandez, 2004: 28). However that figure represents only 29 per cent of Mexico's economically active population (EAP).

Besides all the problems of underemployment and disguised unemployment the Mexican labor force confronts the additional hardship of declining real wages which has been eroding individual and family incomes for over twenty years. Price control policies were implemented after the 1982 crisis and their main objective has been to keep wages down. According to official data the nominal minimum wage increased 150.5 per cent between 1982 and 2002 while at the same time prices rose 618 per cent. As a result purchasing power declined by 75 per cent (El Independiente, 2004: 4-5). The minimum wage in the US is currently more or less ten times greater than Mexico's minimum wage of 46.80 pesos per day —which fluctuates between approximately 4.06 dollars and 4.25 dollars per day depending on the exchange rate. Over one fourth (26.6 per cent) of the working population earns the minimum wage or less. More than half (55.1 per cent) of all those employed earn up to twice the minimum wage, that is, only one fifth of the US minimum or approximately 8.24 dollars per day. Almost three fourths (73.1 per cent) earn up to three times the minimum or approximately 12.54 dollars. The overwhelming majority (86.7 per cent) of Mexican workers earn up to only five times the minimum wage which amounts to approximately half of the US minimum, in other words 20.60 dollars per day.2

Additional official wage data for 2004 indicates that the average wage for workers covered by Mexico's social security system (IMSS) —which as mentioned above covers about 29 per cent of the EAP— was 177.51 pesos per day or about 4 times the minimum wage. However the average contractual wage was reported as 86.91 pesos or only about twice the minimum. The average earnings of retail trade employees (179.95 pesos) was 4.1 times the minimum wage, while for employees in wholesale trade the average ($246.25) was 5.6 times the minimum, and in construction industries ($149.76) it was 3.5 times the minimum wage. The average maquiladora earnings were reported as 243.42 pesos per day which was about 5.6 times the minimum wage. Approximately 2.6 per cent of Mexican workers are employed in the maquiladoras. The average earnings in non maquiladora manufacturing were 364.92 pesos daily which is 8.4 times the minimum wage. Only 2.6 per cent of the labor force is employed in non maquiladora manufacturing. The average wage in manufacturing was reported as 2.44 dollars per hour and the average earnings (wages and salaries) were reported as 5.07 dollars per hour. These figures are consistent with those analyzed in the preceding paragraph since they also indicate that most Mexican workers have incomes equivalent to only five times the national minimum wage or less. Even the most highly paid wage earners, employed in non maquiladora manufacturing, earn significantly less than the US minimum wage (Cuarto Informe de Gobierno, 2004: 223-224).

Given the highly unfavorable conditions that prevail in the Mexican labor market —lack of employment opportunities, growing underemployment and disguised unemployment, growth of the informal economy, declining real wages and incomes for most workers, and greater inequality of incomes with persistently high rates of poverty and extreme poverty— migration to the US appears to be a reasonable option for many of the country's unemployed or underemployed and underpaid workers. Migration to the US rose significantly in the mid 1980s and has continued to grow since then (Romero and Puyana, 2004: 103). Thus throughout Mexico since the early or mid 1980s migration has intensified and become more diverse in terms of the sending regions as well as with respect to destinations.3 Many factors are involved in this process, among others the generally adverse economic conditions, changes in agricultural policies and land tenure regulations, and the fact that many potential migrants have family members, relatives or acquaintances who reside in the US.

As general economic and labor market conditions got worse in Mexico, migration to the US provided an important escape valve for the excess labor supply. Clearly the Mexican government has no interest in limiting this growing out migration. Their main concern is how to make sure that those who have gone will continue to send money back to family members remaining in Mexico. The Central Bank (Banco de México) recognized that as of 2003, remittances from workers in the US have become the country's second source of foreign exchange after oil exports. About one out of every four or five households receives remittances from the US and these flows were essential in bolstering consumer spending in an otherwise stagnant economy, from 2001 to 2003 (Amador, 2003: 20). Up until fairly recently the Mexican government was generally accused of ignoring the vicissitudes of the country's migrants. Recent administrations have made active attempts to maintain and strengthen migrant's ties to Mexico —by approving dual citizenship, supporting and promoting hometown associations, issuing identification cards to those soliciting them at any Mexican consulate in the US, and establishing a mechanism for absentee voting in Mexico's next presidential election— in order to assure the continued flow of remittances, which have become a vital source of income for many families. Nevertheless, in spite of all the increased pressures on the Mexican side, emigration would not have increased nearly as much as it has if migrants weren't able to find jobs in the US with relative ease.

Labor market outcomes for Mexicans and other Latinos in the US

Just as remittances from emigrants have become vital for the Mexican economy, immigrant labor is becoming more and more important for the US economy. The US "experienced the greatest wave of new foreign immigration in its history, with nearly 14 million net new immigrants arriving on its shores between 1990 and 2000." According to Andrew Sum and his coauthors, this record new wave of immigrants played a crucial role in filling the new and old jobs in what had been referred to, before the 2001 recession, as the "New American Economy" (Sum et al., 2002: 2). While many —including George W. Bush and Alan Greenspan— have recognized that immigrant labor played an important role in the unprecedented economic expansion that occurred between 1991 and 2001, others argue that their presence is detrimental to native workers particularly during what has been to some extent a "jobless recovery" from 2002 through 2004 (Camarota, 2004).

In spite of the increasing difficulties Mexican migrants have had to confront after 2001, it seems that they are still finding better employment perspectives north of the border than at home. Since their main motivation for migration is work with better wages, it is not surprising that the Mexican origin population has a higher labor force participation rate (68.9 per cent in 2004) than any other group in the US. The men's rate (82.2 per cent in 2004) is significantly higher than all others' although the women's rate is somewhat lower (54.1 per cent). For the past three decades unemployment rates for Mexican origin Latinos, and in fact for Latinos in general, have been consistently higher than the rates for whites and lower than those for African Americans (6.5 per cent for Mexican origin men in 2004 and 8.5 per cent for women) (U.S. Department of Labor, 2005: 202-203). Mexican origin women are currently the only group that has an unemployment rate higher than that of their male counterparts.

Recently arrived unskilled immigrants almost always end up in the least desirable and lowest paying jobs in the US where they nevertheless earn considerably more than they could in their countries of origin. This has certainly been the experience of most Mexican migrants given their low educational attainment and limited English proficiency. It is often reported that Mexicans who emigrate have more years of schooling than the national average in Mexico which is approximately seven years. Unfortunately this is much lower than the minimum of at least a high school diploma which is required for almost all types of employment in the US. According to Edward P. Lazear of the Hoover Institution, the typical non-Mexican immigrant has a high school diploma whereas the typical Mexican immigrant has less than an eighth-grade education, and about two and a half fewer years of schooling than other Hispanic immigrants. He also maintains that 80 per cent of non-Mexican immigrants are fluent in English compared with 62 per cent of non Mexican Hispanic immigrants and only 49 per cent of Mexican immigrants (Lazear, s/f). These same disadvantages seem to persist for subsequent generations in the US and, no doubt, have an impact on labor market outcomes for many Mexican origin Latinos as well as for most first generation Mexican migrants.

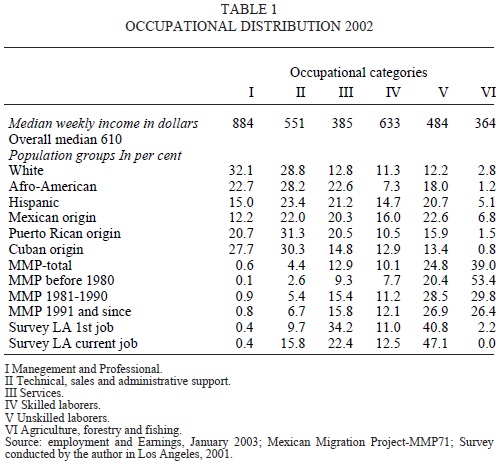

Jorge Durand and Douglas Massey's Mexican Migration Project (MMP) data base provides an interesting point of departure for analyzing Mexican migrant's insertion in the US labor market.4 In order to capture changes in these migrants' occupational distribution over time I established three groups: a) those for whom the last stay in the US ended before 1981, b) those whose last stay ended between 1981 and 1990, and c) those whose last stay took place after 1990 (table 1). More than half (53.4 per cent) of those who made their last trip before 1981 —who were in fact 42 per cent of those interviewed— were employed in agricultural activities. Subsequently the importance of agricultural occupations declined considerably. Only 29.8 per cent of those who went to the US between 1981 and 1990 worked in agriculture and the percent dropped to 26.4 per cent for those migrating from 1991 on. Such changes reflect, above all, the transformations that have taken place in the occupational distribution in the US in general, and also the fact that a growing number of migrants have urban backgrounds. Thus low skilled manufacturing and construction jobs —where employment among the MMP migrants grew from 20.4 per cent in the first period to 26.9 per cent in the third— along with services (which grew from 9.3 to 15.8 per cent) and sales (which grew from 1.8 to 5.5 per cent) and even skilled labor and craft positions (that increased from 7.7 to 12.1 per cent) have been steadily supplanting agriculture as a source of employment for Mexican migrants. Even though Mexican workers now dominate agricultural employment in most regions of the US such activities currently provide jobs for less than too per cent of the total labor force.

Another, although much more limited, source of information on first generation migrants and their occupational outcomes is provided by a survey I conducted among 275 Latinos, attending adult education classes to learn English, in Los Angeles in the spring of 2001.5 Some occupational changes were registered when comparing the respondents' present employment with their first jobs in the US, even though the time elapsed was different in each case, and ranged from one month to 32 years. While no one was employed in agriculture at the time of the survey, 2.2 per cent reported farm work as their first job upon arrival. The percentage employed as unskilled laborers had grown from 40.8 to 47.1 per cent and that of skilled workers increased from 11.1 to 12.5 per cent. Those employed as technical workers, administrative support or sales workers rose from 9.7 to 15.8 per cent. Service sector employment, where wages are often lower than those of even unskilled factory workers, dropped from 34.2 to 22.4 per cent. Improvement in the occupational profile of those surveyed can be explained in part by the fact that several women, who had been employed in private household domestic service, had left the labor force; however the number of men employed in services also declined as some moved into manufacturing jobs.

Labor force participation rates reported were similar to those for the Mexican origin population in the US at that time, approximately 57 per cent for women and over 80 per cent for men. The majority reported regular employment eight hours a day, five days a week. Twelve percent held a second job in the evenings or on weekends. Some women, however, had rather precarious or informal jobs such as caring for children, the sick or elderly, or selling cosmetics or prepared food from their homes. While four respondents held college degrees only one of them, an evangelical pastor from Guatemala, was employed in a position commensurate with his education. Among Latino immigrants social networks are extremely important for obtaining jobs. Seventy eight percent of those surveyed got their first job in the US through a relative or friend and 61 per cent reported having obtained their current employment in this way. While time living in the US ranged from one month to 53 years, slightly more than half had been there for ten years or more. Nevertheless, in general, occupational mobility was limited and most had household incomes either below or not much above the poverty thresholds.

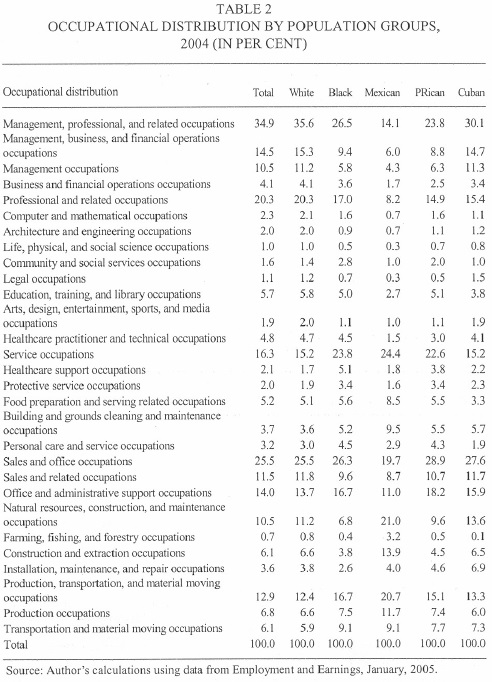

US Labor Department data for the Mexican origin labor force as a whole shows that it is now more or less evenly distributed among four of the five major occupational category classifications: Service occupations 24.4 per cent; Sales and office occupations 19.7 per cent; Natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations 21.0 per cent; and Production, transportation and material moving occupations 20.7 per cent.6 Participation in Management, professional and related occupations (14.1 per cent) is considerably lower than for any other racial or ethnic group (see table 2).

Only 3.2 per cent of the Mexican origin labor force is employed in farming, fishing and forestry occupations but that far exceeds any other group's participation in those activities. Significant numbers of Mexican origin workers are employed in production and construction occupations (11.7 and 13.9 per cent, respectively) where there are some high paying jobs for highly skilled and experienced workers, along with many lower paying jobs for the less skilled. Eleven percent are employed in office and administrative support jobs. These tend to be female dominated occupations with moderately low earnings levels. This is also the case for many of the sales related occupations that employ 8.7 per cent of the Mexican origin labor force. An additional 8.5 and 9.5 per cent, respectively, work in food preparation and serving occupations and building and grounds cleaning and maintenance occupations. Wages tend to be extremely low in these last two categories (U.S. Department of Labor, 2005: 210-217, 250-254).

Another way of analyzing labor market outcomes for Mexican workers is to see how concentrated they are in specific occupational categories and to look at median earnings in categories that have particularly high percentages of Mexicans. The Labor Department's detailed occupation tables only provide information for the entire Latino population; it is not disaggregated by national origin (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004: 209-213, 249-253). However since Mexican origin Latinos usually constitute about two thirds of all Latinos in the US, and Mexicans were 64 per cent of the Latino labor force in 2003, the degree of Latino participation in each occupational category is probably a satisfactory proxy for the degree of Mexican participation in most cases. In all of the cases where the concentration of Latinos was high or very high (that is too or three times higher than the percent they represent in the total labor force which was 12.6 per cent in 2003) median weekly earnings were significantly lower than the overall median of 620 dollars. Among these, only skilled construction workers —three out of the 30 occupations where 25.6 per cent or more of the workers are Latinos— registered median earnings anywhere close to the general median. Latinos showed varying degrees of concentration (in other words they made up 12.6 per cent or more of the labor force employed) in 102 of the Labor Department's 302 detailed occupational categories. However median earnings were above the overall median in only ten of these 102 occupations. On the other hand, out of the remaining 200 occupations where Latinos were underrepresented (where they were less than 12.6 per cent of those employed) two thirds of these showed median earnings above the overall median. Thus even at this highly aggregated national level it is quite clear that Latino workers are extremely concentrated in low wage or otherwise undesirable or dangerous jobs.

The increased Latino presence since the early 1990s is quite noticeable in some of these occupations where it has almost, or even more than, doubled since then, such as food preparation workers, automotive body and related repairs, pressers in textile and garment production, carpenters and cabinet makers, drywall installers, cement masons and concrete finishers. In other cases where the percent of Latinos is particularly high —butchers and other meat and poultry processors, hand packers and packagers, building service maids janitors and cleaners, sewing machine operators, packaging and filling machine operators, and grounds maintenance workers, for example— the increment is considerable but less dramatic because their presence was already quite high over a decade ago. While the Latino presence in agricultural occupations appears to have grown —with an increase from 17.1 to 40.3 per cent of those employed— the relative gain is hiding a real decline of one third in the number of Latinos employed (from 621 thousand to 423 thousand) because total employment in agriculture dropped by 71 per cent over the last decade or so (U.S. Department of Labor, 1995 and 2004).

Even though women now make up almost half of the US labor force (46.5 per cent in 2004) they still confront high degrees of de facto occupational segregation and wage discrimination, in spite of legislation prohibiting such practices. Latina and African American women experience labor market discrimination derived from the combined effects of both gender and race or ethnicity (Brown, 1999). Mexican origin Latinas, who tend to be among the lowest paid workers throughout the US, are further limited by their low levels of educational attainment. In general there are more women employed, both relatively (as a per cent of all women employed) and absolutely (as a per cent of all workers) in what are often referred to as white collar and pink collar occupations, which include professional and related occupations and sales and office occupations respectively, and in service occupations; while blue collar occupations and agricultural related activities are, on the whole, dominated by men. This trend also holds for Mexican origin men and women in the labor force.

Among and within and each of these broad general categories women, and especially Latina women, tend to be concentrated in the more subordinate and/ or lower paying sub categories. For example, men dominate managerial posts and most office and administrative support occupations are female dominated. There are more men teaching at the post secondary level, and more women teaching at all lower levels. There are about twice as many male as female lawyers, whereas most of the paralegals, legal assistants and other legal professionals are women. There are more male than female supervisors of both retail and non-retail sales workers but 76 per cent of all cashiers are women. While most production occupations are male dominated, there are a few areas where the majority of the workers are women, such as electrical and electronics assemblers, packaging and filling machine operators, and textile and garment industry workers. In each of these areas median weekly earnings are below the overall median for production occupations ($526 in 2004), which is in turn much lower than the overall median ($638). Even within the same specific occupational categories women tend to have lower median weekly earnings than men (U.S. Department of Labor 2005: 210-215, 250-254).

There are some female dominated occupations where the concentration of Latina workers is also relatively high or at least higher than the Latino component of the labor force which was 12.6 per cent in 2003. In all of the 32 specific occupations where both of these conditions hold, median earnings were well below the overall median ($620 in 2003) and in only two cases was it higher than the median for all fulltime female workers, which was $552. In those categories where Latina concentration is highest (over 37 per cent which is approximately three times greater than Latinos' representation in the labor force as a whole) median weekly earnings are extremely low. This situation holds for the following occupations: pressers of textile, garment and related materials ($323); graders and sorters of agricultural products ($387); hand packagers and packers ($348); maids and housekeeping cleaners ($323); sewing machine operators ($344); packaging and filling machine operators ($390) (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004).

There has been some significant growth, over the past decade, in Latino concentration by industry, as well, which generally coincides with the occupations data. Between 1994 and 2003 the proportion of Latino workers in the labor force as a whole grew from 8.8 to 12.6 per cent, while in animal slaughtering it rose from 25.0 to 43.4 per cent. In landscaping services it grew from 25.2 to 36.8 per cent, in cut and sew apparel it went from 23.1 to 35.5 per cent, in services to buildings and dwellings from 20.3 to 31.0 per cent, and in dry cleaning and laundry services it rose from 15.7 to 30.9 per cent. In the area of food manufacturing in general the increase was from 18.3 to 29.1 per cent, and it was even more pronounced in a few specific sub sectors (in sugar and confectionary products it rose from 16.1 to 31.7 per cent and in bakery products from 13 to 29 per cent). However carpet and rug mills showed the most spectacular increase. In just ten years Latino participation in this industry rose form 6.3 to 37.8 per cent (U.S. Department of Labor 1995: 188-191 and 2004: 225-229). Dalton Georgia is the rug and carpet capital of the US, often referred to as "carpet city", and its mills now rely heavily on Mexican labor.

There are also several female dominated industries (i.e. where women constitute 50 per cent or more of those employed therein) particularly in the areas of retail trade, educational and health services, accommodation and food services, and some areas of professional and business services, and other services. However Latina presence is only highly significant7 in a few of these, such as sugar and confectionary products; retail bakeries; textiles, apparel and leather; soaps, cleaning compounds and cosmetics; and traveler accommodation. It is extremely significant (over 30 per cent) in cut and sew apparel; services to buildings and dwellings; dry cleaning and laundry services; and private household services (U.S. Department of Labor, 2005: 226-230). All of these are generally considered to be low wage industries. For live in domestic service actual wages may be extremely low since part of the compensation is provided through room and board. Private household service is particularly important as a form of first entry into the US labor force for many Latina women. According to Labor Department statistics it employs about 3.4 per cent of all Latina workers. However there is a high degree of informality in private household service work thus official figures may, in fact, understate its significance.

Since 75 per cent of all Latinos reside in just seven states, labor market segmentation and stratification for them is, in fact, probably even more pronounced than these national figures indicate. No doubt, occupational concentration and geographical concentration are closely linked. However Latinos are often recruited for, or encouraged to settle in, non traditional destinations in the southeast and Midwest to fill jobs in agriculture, poultry processing, meat packing plants, or carpet mills, for example, that local residents disdain. These and other "immigrantjobs" or "immigrant labor market niches" as they are frequently called, usually offer working conditions or salaries that most US born workers won't accept. The demand for workers to perform such tasks, for low wages, increased dramatically towards the end of the twentieth century as did the new wave of immigrant workers, particularly those from Mexico and other Latin American countries, who were willing to fill those jobs (Sum etal., 2002). The non Hispanic labor force is projected to grow only nine per cent between 2000 and 2010. The Latino labor force will probably increase by 77 per cent due to the combination of newly arriving immigrants and the number of young US Latinos who will reach working age. Thus by 2010 Latinos are projected to constitute about 17.4 per cent of the EAP (Vernez and Mizell, 2003).

Although Latinos are a significant and growing share of the US labor force, "working Latinos have had persistently high rates of poverty and unemployment, as well as low incomes" (Breitfeld, 2003: 1). As was mentioned earlier, for the past several decades unemployment rates for Latinos have consistently been slightly lower than African Americans' unemployment figures and higher than those for non Hispanic whites. Their relative earnings, however, have deteriorated (Levine, 2001). Since the early 1980s, in the case of female workers, and from the early 1990s to the present, for men, Latino workers have had lower median earnings than any other population group. Median earnings for Latino men (graph 1) is slightly lower than the median for Afro American men ($21 053 per year and $21 935, respectively in 2003) and much lower than the median for non Hispanic white men ($32 331 in 2003). In the case of men who work full time year round (graph 2) Latinos have consistently had a lower median than Afro Americans since the mid 1980s and the gap is growing ($26 414 vs. $33 464 per year in 2003) as it also has between Latino men and non Hispanic whites (whose median earnings were ($46 294 in 2003). Median earnings for Latina women ($13 642 in 2003; see graph 3) is much lower than for African American women ($16 540), whose median is only somewhat lower than non Hispanic white women's ($18 301). In the case of women who work full time year round (graph 4), Latinas have had lower median earnings than Afro Americans and non Hispanic whites since the early 1970s when such statistics were first recorded, and the gaps have been growing consistently. The figures were $23 062, $27 675, and $34 037, respectively in 2003 (Current Population Survey, 2005). Mexican origin men and women tend to have lower median earnings than other groups of Latinos in the US (Levine, 2001).

The differences in Latinos' and African Americans' median family and household incomes with respect to non Hispanic whites' is growing; nevertheless Latinos have slightly higher medians (for families8 and households) than African Americans. This latter difference is not derived from higher individual earnings —we have just seen above that both Latino men and women tend to have lower earnings— but from the fact that there are usually more workers per family or household. Adolescents often drop out ofhigh school before graduating in order to contribute to family income or even, as is sometimes the case for females, to take care of younger siblings so that the mother can work outside of the home. Many Latino households include extended family members —aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, grandparents, etc.— and often non family members who may be from the same home town. The net effect is that slightly higher median family and household incomes are divided among a greater number of individuals so that from 1988 on Latinos' per capita income has been somewhat lower than African Americans' and much lower than non Hispanic whites'. The per capita income figures were 13 492, 15 583, and 26 774, dollars per year, respectively, in 2003 (Current Population Survey, 2005).

Increasing labor market segmentation in the US has a negative impact on Latinos' incomes. Lisa Catanzarite analyzed data for 38 different metropolitan areas and found that wages were lower in what she has called "brown collar occupations" where significant numbers of Latinos are employed. These wage differentials have a larger impact on racial and ethnic minorities than for non Hispanic whites and mainly affect earlier Latino immigrants, since they are the ones most likely to be employed in these sectors. She cites "devaluation of the work performed by low status groups; the poor market position of labor intensive occupations; the limited political power of low status workers; and the willingness of low status workers to accept poor wages" as the underlying causes of the observed differentials (Catanzarite, 2003: 3). A recent National Council of La Raza (NCLR) document on the Latino workforce points to low levels of educational attainment as a fundamental reason why Latinos tend to be concentrated in low skilled, low paying occupations and industries with little access to fringe benefits. However, the author also mentions other contributing factors such as discrimination, immigration status, and (lack of) union participation (Breitfeld, 2003).

Given the low wage rates for Latino workers it is no surprise that in 2001 they were slightly more likely to be poor than African American workers (11.2 vs. 10.4 per cent) and much more so than white non Hispanic workers (by 4 per cent). This was also true, though to a lesser degree, for fulltime workers; Latino full timers had a poverty rate of 6.5 per cent, Afro Americans 4.4 per cent and non Hispanic whites 1.7 per cent (Breitfeld, 2003). The second half of the twentieth century brought a very significant decline in the poverty rate for African Americans, in general. It dropped steadily from 55.1 per cent in 1959 to 32.2 per cent in 1969, and fluctuated around 30 per cent till the early 1980s. After 1992 it dropped again from 33.4 to 22.7 per cent in 2001 and then rose to 24.7 per cent in 2004. Meanwhile the Latino poverty rate rose from 21.9 per cent in 1972 to 30.7 per cent in 1994, fell back to 21.4 per cent in 2001, then rose slightly to 22.5 per cent in 2003, and receded a bit to 21.9 per cent in 2004. Even so, the Latino poverty rate was higher than the African American rate from 1994 to 1997. Furthermore, while African Americans now constitute a smaller percentage of those living in poverty in the US —down from 31.1 per cent in 1966 to 25.4 per cent in 2004— Latinos now constitute a much larger percentage, up from 10.3 per cent in 1973 —when they were a much smaller portion of the total population— to 24.7 per cent in 2004 (Current Population Survey, 2005). In other terms, Latinos who now make up about one eighth of the US population are one fourth of those living below the poverty threshold.

Wage differentials for Latino immigrants and subsequent generations can be largely explained by differences in educational attainment (Lowell, 2004. Unfortunately Mexican born workers seem to have lower returns to educational attainment than all other groups and there are more Mexicans than other Latinos with less than a high school education. Only 50.9 per cent of Mexican origin Latinos 25 and older had high school diplomas or more in 2003, compared with 69.7 per cent for Puerto Ricans and 70.8 per cent for Cubans. The high school completion rate for whites in general was 85.1 per cent and for blacks or Afro-Americans it was 80 per cent. At the same time only 7.8 per cent of the Mexican origin population had a college degree or more, compared with 27.6 per cent of all whites and 17.3 per cent of blacks or Afro-Americans. The figures for Puerto Rican and Cuban origin Latinos were 12.3 and 21.6 per cent, respectively (US Census Bureau, 2005: 141). Nevertheless, and in spite of the fact that in some Mexican families schooling for boys is still given more importance than it is for girls, the educational attainment profile for Mexican origin females in the US is slightly more favorable, or a bit less unfavorable, than that of males. There is a slightly lower percentage of females with less than 9th grade (31.3 per cent females vs. 32.8 per cent males) and slightly higher percentages with high school graduation (26.9 vs. 26.5 per cent), some college or Associates Degrees (17.0 vs. 15.8 per cent), and Bachelors Degrees (5.9 vs. 5.5 per cent); while males have a minimal advantage in terms of advanced degrees (2.1 per cent for males and 1.7 per cent for females) (Current Population Survey, 2005).

Lindsay Lowell found that from 1994 to 2002 Mexican born workers who were not high school graduates had slightly higher weekly earnings than others without a high school diploma; nevertheless these are the lowest paid members of the labor force. For high school graduates and holders of Bachelor's degrees or advanced degrees Mexican born workers had lower wages than all other groups. Thus not only do Mexicans earn less because of lower educational attainment, but also because they tend to get lower returns to education from high school graduation onwards. Furthermore these differentials continue, although to a lesser degree, for second and third generations and up (Lowell, 2004). For many Mexicans, henceforth, educational attainment and incomes or socioeconomic status appear to be not only highly correlated but also mutually determined and reinforcing across generations.

Unfortunately, women at all levels of educational attainment have lower average earnings than their male counterparts. The differences are greatest for white women with respect to white men and tend to rise as educational attainment increases (graph 5).

The differences are lowest for African American women with respect to African American men, except for the very small difference in mean earnings for Latinos with Master's degrees, who are in turn a very small percent (3.1 per cent) of the Latino population(US Census Bureau, 2005: 141).

These somewhat less pronounced differentials for African American and Latina women with respect to their male counterparts are not, however, the result of a more favorable labor market position. They reflect the much less favorable labor market outcomes that all groups, including white women, have with respect to white men at the same educational levels. Among Latinos, Mexicans have to lowest levels of educational attainment; and Latinos overall, because of the high Mexican component, have lower levels of educational attainment than non Hispanic whites or African Americans.

Conclusions

Globalization and economic restructuring at the international level, combined with internal factors, such as the high levels of corruption and economic policies aimed only at conserving the vested interests of dominant elites, have had devastating effects for most of the Mexican population. As a result, migratory pressures have increased over the past two decades rather than waning. Instead of moving towards a more diversified and better integrated industrial sector with greater forward and backward linkages, Mexican industry has become even less integrated domestically and more dependent on imported inputs and technology. Thus, achieving export oriented industrialization that could significantly increase demand for the country's growing labor force has proven to be an elusive goal. Rapidly deteriorating labor market conditions in Mexico —characterized by declining real wages, insufficient job creation to absorb the increasing labor supply, and marked expansion of the informal labor market— go a long way towards explaining why low wage jobs in the US are so attractive for Mexican migrants.

As general economic and labor market conditions got worse in Mexico, since the early 1980s, migration to the US proved to be an important escape valve for the excess labor supply. It provides income for migrants' families remaining in Mexico, and has become an important source of foreign exchange. For many Mexican women jobs in the US provide their first experiences as members of the paid labor force. Clearly the Mexican government has no interest in limiting this growing out migration. In fact, recent administrations have made clear attempts to maintain and strengthen migrant's ties to Mexico in order to assure the continued flow of remittances. However, in spite of all the increased pressures on the Mexican side, emigration would not have increased nearly as much as it has if migrants weren't able to find jobs in the US with relative ease.

Immigrant labor is becoming more and more important for the US economy and the occupational profile of Mexican migrants is changing rapidly. Only a very small percentage of the Mexican origin population is currently employed in agriculture. Over the past few decades more and more recent Mexican immigrants have found work in low skilled manufacturing and service sector jobs. The demand for workers to perform such tasks, for low wages, increased dramatically towards the end of the twentieth century as did the new wave of immigrant workers from Mexico, and other Latin American countries, who were willing to fill those jobs. By 2010 Latinos are projected to constitute about 17.4 per cent of the US labor force. Certain occupations and industrial sub sectors have rapidly become "immigrant niches" within the US labor market.

Nevertheless, in spite of their growing importance as part of the labor supply, many Latinos who live and work in the US have persistently high rates of poverty and unemployment, as well as very low incomes by US standards. Since the early 1980s, in the case of female workers, and from the beginning of the 1990s to the present, for men, Latino workers have had lower median earnings than any other population group. Mexican origin Latinos tend to be among those with the lowest incomes. Income inequality is clearly on the rise in the US and increasing labor market segmentation has had a negative impact on Latinos' earnings. Latinos now constitute a large and disproportionate percentage of those living below the poverty threshold. Mexican origin women in the US labor force clearly suffer from the combined effects of both gender and ethnic discrimination in terms of occupations and earnings.

Growing wage differentials for Latino immigrants and subsequent generations can be largely explained by differences in educational attainment. There are more Mexican origin Latinos with less than a high school education and fewer with college degrees than for any other group in the US. Not only do Mexicans earn less because of lower educational attainment, but also because they tend to get lower returns to education from high school graduation onwards. There are many mutually reinforcing connections between educational attainment and incomes which work to the disadvantage of most Latino immigrants as well as subsequent generations, particularly those of Mexican origin since they have the lowest educational attainment and the lowest incomes. While educational attainment is not the only factor that determines low wages for Latinos, it can easily be used to justify and disguise other discriminatory practices. Unfortunately, in the US today, women from all racial and ethnic groups still earn considerably less than their male counterparts with similar levels of educational attainment.

Several decades ago, almost any progress in terms of educational attainment could be expected to bring some improvement in terms of income. Immigrants and others who graduated from high school could at least aspire to well paying jobs in manufacturing. Given the labor market conditions prevailing in the US today, this option is no longer open to most of those among today's youth who for one reason or another can't expect to earn a college degree. In today's more stratified and segmented economy, with greater income differences and skills differences than ever before, it cannot be taken for granted that the problem of lower educational attainment and lower socioeconomic status experienced by specific groups will rapidly disappear for subsequent generations.

At the end of 2005, the US seemed to be moving further away from, rather than closer to, any sort of immigration legislation that would mitigate the hardships faced by most Mexican migrants, who are generally welcomed as low waged workers yet not as residents. However, the stalemate in the Senate in March of 2006 may subsequently produce a proposal for a much larger and comprehensive guest worker program and possibly even the eventual regularization, of millions of currently undocumented workers, well over 50 percent of whom are presumed to be Mexican. Nevertheless, even this more favorable scenario will mean that most of the Mexicans migrating to the US during the next several years will be trading precarious low paying jobs at home for mainly precarious and low wage jobs in the US.

Bibliography

BACON, David, 2004, "The children ofNAFTA. labor wars in the U S/Mexico border", quoted in Alejandro Alvarez, A 10 años del TLCAN ¿Apetitosa neocolonial de jóvenes sin futuro?, Memoria, num. 187, September, 12 University of California Press, Berkley and Los Angeles. [ Links ]

BREITFELD, Thomas, 2003, "The Latino workforce", in Statistical Brief num. 3, National Council of La Raza, Washington. [ Links ]

BROWN Irene, 1999, s/f, Latinas and African American women at work, Russell Sage Foundation, Nueva York. [ Links ]

CAMAROTA, Steven, 2004, A jobless recovery? Immigrant gains and native losses, Backgrounder, Center for Immigration Studies, october, Washington. [ Links ]

CATANZARITE, Lisa, 2003, "Wage penalties in brown collar occupations", in Latino Policy and Issues Brief, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, núm.8, september. [ Links ]

CLINTON, William, 1993, "Remarks by the President During 'A California town hall meeting'", The White House office of the Press Secretary, October 3, 1993, quoted in Manning Robert and Anita Cristina Butera, Global restructuring and U.S.-Mexican economic integration: rhetoric and reality of Mexican immigration five years after NAFTA, American Studies, 41:2/3. [ Links ]

CUARTO INFORME DE GOBIERNO, 2004. Anexo estadístico.

CURRENT POPULATION SURVEY, 2005, Internet Release.

DURAND, Jorge and Douglas S. Massey, 2003, Clandestinos, Migración Mexico Estados Unidos en los albores del siglo XXI, Miguel Angél Porrúa, México. [ Links ]

FERNANDEZ, Vega, Carlos, s/f, "El trabajo barato sostiene la economía, aunque Fox no lo crea", en La Jornada, march 3.

GONZALEZ Amador, 2003, Robert "Las remesas de EU mantienen el consumo interno en México", en La Jornada, february 4.

KOCHHAR, Rakesh, 2005, "Survey of Mexican Migrants, Part Three: the economic transition to America", Pew Hispanic Center, Washington. [ Links ]

LAZEAR, Edward, s/f, The plight of immigrants from Mexico, Hover Institution. [ Links ]

LEVINE, Elaine, 2005, "El proceso de incorporación de inmigrantes mexicanos a la vida y el trabajo en Los Ángeles", in Migraciones Internacionales, 9, vol. 3, num 2, july-december. [ Links ]

LEVINE, Elaine, 2001, Los nuevos pobres de los Estados Unidos: los hispanos, Miguel Ángel Porrúa and IIEc. and CISAN/UNAM, Mexico. [ Links ]

LOWELL, Lindsey, 2004, "Human capital and the economic effects of Mexican migration to the United States", paper presented in the Seminar Migración México, Estados Unidos: Implicaciones y retos para ambos países, december 1, México. [ Links ]

MANNING, Robert and Anita Cristina Butera, 2000, "Global restructuring and U.S.Mexican economic integration: rhetoric and reality of Mexican immigration five years after NAFTA", in American Studies, 41:2/3. [ Links ]

MARTINEZ, Fabiola, 2004, "En la economía informal, 62% de los empleos de México: OIT", en La Jornada, june 12.

ORTIZ Rivera, Alicia, s/f, Banco de México data quoted in "Hijos del salario Mínimo", en El Independiente, August 15.

PASSEL, Jeffrey, 2005, Unauthorized migrants: numbers and characteristics, Pew Hispanic Center. [ Links ]

POLASKI, Sandra, 2004, "Perspectivas on the future of NAFTA: Mexican labor in North American integration", paper presented at the Colloquium El Impacto del TLCAN en México a los 10 años, UNAM, june 29-30, mexico. [ Links ]

ROMERO and Puyana, 2004, "Evaluación integral de los impactos e instrumentación del capítulo agropecuario del TLCAN", paper presented at the Colloquium El Impacto del TLCAN en México a los 10 años, UNAM, june 29-30, Mexico. [ Links ]

SALAS, Carlos, 2003, "El contexto económico de México" in Enrique de la Garza and Carlos Salas, coordinators, La situación del trabajo en México, 2003, Plaza y Valdés, Mexico. [ Links ]

SUM, Andrew et al., 2002, Immigrant workers and the great American job machine: the contribution of new foreign immigration to the national and regional labor force growth in the 1990s, prepared for National Business Roundtable, Washington. [ Links ]

SURO, Robert and Jeffrey S. Passel, 2003, The rise of the second generation: changing patterns in Hispanic population growth, Pew Hispanic Center. [ Links ]

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, 2005, Author's calculations based on Employment and Earnings, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington. [ Links ]

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, Employment and Earnings, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington. [ Links ]

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, 2004, Employment and Earnings, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington. [ Links ]

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, 2005, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington. [ Links ]

US CENSUS BUREAU, 2005, Statistical abstract of the United States 2004-2005, USGPO, Washington. [ Links ]

US CENSUS BUREAU, 2005, Statistical abstract of the United States 2004-2005, USGPO, Washington. [ Links ]

VERNEZ, George and Lee Mizell, 2001, Goal: to double the rate of Hispanics earning a bachelor's degree, Rand Education, Center for Research on Immigration Policy, Washington. [ Links ]

ZARSKY, Lyuba and Kevin P. Gallagher, 2004, TLCAN, inversion extranjera directa y el desarrollo industrial sustentable en México, Ameritas Program, Silver City, NM, Interhemispheric Resource Center, march. [ Links ]

* The author wishes to thank the UNAM's Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica/PAPIIT (Program to Support Research and Technological Innovation Projects) for supporting the research for this article by funding the project IN308205 Los Latinos en Estados Unidos, quiénes son, dónde están y a qué desafíos se enfrentan. She also thanks Marcela Osnaya for technical assistance. An earlier version of this article appears in the Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies, vol. 2, num. 1, spring 2006.

1 Jobs registered by the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social IMSS rose by 1 828 thousand and those registered in the Instituto de Seguridad Social al Servicio de los Trabajadores del Estado ISSSTE rose by 310.3 thousand, the net increase registered in maquiladora employment was 568.5 thousand (Cuarto Informe de Gobierno, 2004).

2 Calculations based on applying the current minimum wage rate to wage distribution data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, INEGI's labor census for the year 2000, quoted in Ortiz (s/f: 4-5).

3 For a more comprehensive vision of recent changes in migration trends and characteristics see Durand and Massey (2003).

4 Mexican Migration Project, MMP71, www.popupenn.edu/mexmig; the author wishes to thank Marcela Osnaya for her support in processing the Mexican Migration Project data and also the capture and processing of my Los Angeles survey data referred to subsequently.

5 For a more detailed analysis of the survey results see (Levine 2005: 108-136).

6 Author's calculations based on Employment and Earnings, U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, D. C., anuary, 2005, p. 216-217. As of2004, that is with the data for 2003, the Labor Department modified the way the occupational categories list is organized, by regrouping various occupations and somewhat modifying the major headings. For example, farming forestry and fishing is no longer listed as a separate major category and has been included as a sub heading under Natural resources, construction and maintenance occupations.

7 We have considered Latina presence as highly significant when it is at least 1.5 times higher than the Latino presence in the labor force which is 12.9 per cent for 2004, in other words a figure of 19.4 percent

8 This is generally true in the case offamilies; however from 1993 to 1997 and in 1999 and 2003, African American families had higher median earnings than Latinos families.

Información sobre la autora

Elaine Levine. Realizó sus estudios de licenciatura y maestría en Economía en los Estados Unidos y es doctora en Economía por la Facultad de Economía de la UNAM. Ella es investigadora titular del Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte (CISAN) de la UNAM. También es profesora del Posgrado en Ciencias Políticas y Sociales de la UNAM y miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores. Es especialista en la economía estadunidense, con interés especial en el mercado laboral, la distribución del ingreso, y el estatus socioeconómico de la población latina en aquel país. Durante el año lectivo 2000-2001 fue investigadora visitante en la Universidad de California, Los Angeles, con el apoyo de una beca Fulbright-García Robles. Ha publicado numerosos artículos en revistas especializadas y capítulos de libros colectivos. Su libro Los nuevos pobres de Estados Unidos, los hispanos, fue publicado en el 2001 por la editorial Miguel Angel Porrúa en coedición con el Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y el CISAN. Correo electrónico: elaine@servidor.unam.mx.