Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Papeles de población

versión On-line ISSN 2448-7147versión impresa ISSN 1405-7425

Pap. poblac vol.10 no.39 Toluca ene./mar. 2004

Moving north: different factors influencing male and female mexican migration to United States

Movimiento hacia el norte: los diferentes factores que afectan la migración mexicana femenina y masculina a Estados Unidos

Vladimir Canudas Romo

Pennsylvania State University.

Abstract

This paper employs survival analysis to study the Mexican patterns of migration to the United States for working purposes. The model focuses on certain factors which have been distinguished previously as characteristics of labour migration: age, family responsibility, family network, education, labour status and calendar year. Special emphasis has been put on distinguishing between male and female characteristics. The data used derives from the EDER, a retrospective survey elaborated in Mexico. Estimates show a reduction in the migration risk for men and women due to employment in Mexico and the formation of a union, respectively. The most important contribution of this project is the emphasis on the change over time of the influence of these different factors on the risk to migrate to the United States.

Keywords: migration, gender, event-history data, EDER.

Resumen

Este artículo emplea análisis de sobrevivencia para estudiar los patrones mexicanos de migración a los Estados Unidos por motivos laborales. El modelo se enfoca en ciertos factores que se han distinguido previamente como característicos de la migración laboral: edad, responsabilidad familiar, redes familiares, educación, estatus laboral y el año calendario. Se ha puesto especial énfasis en distinguir entre las características masculinas y femeninas. Los datos utilizados provienen de la EDER, una encuesta retrospectiva elaborada en México. Las estimaciones muestran una reducción en el riesgo de migrar para hombres y mujeres debido al empleo en México y la formación de una unión, respectivamente. La contribución más relevante de este proyecto es el énfasis en el cambio en el tiempo de la influencia de los distintos factores en el riesgo de migrar a Estados Unidos.

Palabras clave: migración, género, datos evento-calendario, EDER.

Introduction

The North American migration is the most dynamic of all contemporary international migration movements. Its principal destination is the United States and the largest migration flow goes from Mexico to the US (Massey et al., 1998). During the period 1981-1995, about 3 million legal Mexican immigrants were accepted by the US. However, the legal immigrants provide only the bottom line for the unknown number of total migration (Martin, 1996). In the first years of the nineties, the migration reduced the Mexican population growth rate with the same amount as mortality improvements increased it; approximately 20 per cent of the total population growth (Partida, 1998). This flow of people involves a lot of exchange which makes relevant to study the characteristics and explanatory factors of the migrants, at both sides of the Mexico-US border.

Contemporary theories of international migration sustain their hypotheses by using certain factors to explain population movement. Neoclassical economics explain Mexico-US migration by the binational wage gap, using demographic factors influenced by wages. Social capital theory refers to networks as an explanatory factor for migration, using kinship ties in the US to explain it. The new economics of labor migration assumes an importance of risks in access to capital, using national indicators as inflation and currency devaluation as predictors. Segmented labor market theory builds its arguments based on the specific demand of the receiving countries for its labor force. A thorough review of these theories can be found in the study of Massey and Espinosa (1997). Sex is often included as an important factor in theories of international migration. Nevertheless, research on migration has so far done little in gender differentiation (Cerrutti and Massey, 2001). Some of the few authors that have incorporated separate models for males and females are Donato and Kanaiaupuni (2000) and Cerrutti and Massey (2001).

This article includes several factors to study Mexican migration to the US with a gender distinction. Most of the factors pertain to migration theories at the individual level such as: education enrollment, union status, labor status and presence of siblings in the US. In addition, we examine for the period effects by analyzing the influence of national events on the risk of migration. Changes in any of these factors influence the probability of migration, either by increasing or decreasing it and we examine the magnitude of these effects.

The next section includes the data and methods used here. Then all the results of the characteristics included in this research are analyzed in different subsections. Following this analysis, it is examined how different events influence the risk of migration using two idealized Mexicans. We include unobserved heterogeneity in our model in a section preceding the conclusions.

Data and methods

The data derives from the National Retrospective Demographic Survey; EDER for its name in Spanish, which was carried out in Mexico in 1998. The retrospective survey with duration data is representative of the entire population of the country and it includes 2 496 persons. Three cohorts of Mexicans were interviewed: those born in 1936-1938, 1951-1953, and 1966-1968. For each person, individual events are related to calendar time, from the year of birth to the moment of the survey in 1998. The event-history data of each individual covers five areas of interest: migration history, labor history, education history, family history, and fertility history. Details on the survey can be found in EDER (1998).

A hazard model is developed for studying the risk of labor migration to the US. This model is implemented by using the software aML (Lillard and Panis, (1998).

Figure 1 shows the status and transition diagram for labor migration with Mexico as the country of origin and US as the destination.

In this diagram, the status never working, working and unemployed, on the left, are in Mexico and on the right is the status of working in the US. The present study is concerned with the migration to United States for working reasons, which is represented in the diagram by the transitions?. The event of migrating to work in the US has as a competing event changing in labor-market attachment in Mexico, represented in the diagram by the transitions?. Factors related to sex, age, educational enrollment, period, and the family histories are added as explanatory variables.

The data only included Mexican residents in 1998. Some of these individuals did at a certain point in time before 1998 experience temporary labor migration to the US. These individuals are the so called sojourners, those who after certain time would return to the country of origin.1 The results can not be generalized to persons who settled in the US and therefore were not Mexican residents in 1998. Cornelius and Enrico (2000) analyzed these different types of migrants. This distinction remains essential for an understanding of the present study.

From the EDER survey we selected the factors described below. Among the fixed factors are the censoring option (1 for not migrated, 0 for migrated or censored), sex and year of birth. Also dichotomous fixed factors (yes = 1, no = 0) were included for answering the questions: did the person ever attend school? Did the person ever live in a union? Did the person ever have a child? And did the person ever work? Other factors included are the ages when education enrollment started, union started, when having the first child, and when working began. Finally, the number of siblings living in the US was included as a fixed factor.2

The time-varying factor age of the person is our time mark. Education, union status, parity and labor status change over time into different levels. Education has six levels: 0 -no education, 1 -attending elementary school, 2 -attending junior high or similar attended, 3 -dropped school with elementary education, 4 -dropped school with junior high education and 5 -attending more than junior high education. Union status has four levels: 0 -not in a union, 1 - married or in a union, 2 -separated and 3 -partner dead. Parity has five levels: from 0 to 4 or more children. The last time-varying factor is labor status with four levels: 0 -the person has never worked, 1 -the person is employed, 2 -the person is unemployed and 3 -the person has a work in the US.

A hazard rate model including fixed and time-varying factors can be summarized by the following mathematical representation

where y(t) is the baseline, xik (t) are time-varying and fixed (xik (t) = xik) covariates, Ui is a term accounting for unobserved heterogeneity, and βk are coefficients. In the following section, each factor is explained and formula (1) is elaborated step by step. Time t is the age of the individual.

Characteristics of the Mexican migration

Gender

Historically, Mexican women have participated less than men in the international migration. During the 1970s and the 1980s, a shift in the gender composition of Mexican migration was observed (Cornelius and Enrico, 2000). As more single women and whole families began to cross the border, migration became less male-dominated. Although the gender difference has declined in recent years, it is expected to still be prevalent in this analysis. Gender differences in migration reflect a sexual division of labor, which is still common in Mexico, even though it is becoming less prominent.

The economic improvement is one of the benefits of female migrants but also advances in their social status are important. As suggested by Zahniser (1999), female migrants from Mexico tend to experience greater autonomy, exercise greater authority within the family, and perform less housework than they did in Mexico.

Before the 1990s, the male part of the temporary migration constituted around 84 per cent of the total temporary migration (Garcia and Griego, 1988). Resent findings show increased female participation in international migration. Cornelius and Enrico (2000) suggest that the increase is partly due to family reunification.3 Other hypotheses are that social contacts facilitated male migration in the past but were less useful to Mexican women, and that this pattern has changed in the present days. Mexicans males and females, might have valued leaving their family for extended periods of time in different ways, making women less likely to migrate across the border (Zahniser, 1999).

Separate analysis was carried out for males and females in this study. Our initial hazard models have the following representation for females

And for females

However, in the model examining heterogeneity in the last section both sexes are included.

In the rest of the article, the different factors that influence male and female Mexican migration to the US are discussed.

Age patterns

Young adult Mexicans are expected to be more likely to migrate than the very young and the very old. Previous studies indicate that the probability of migration first increases when a person initially gets older and then decreases as he or she becomes increasingly aged.

Table 1 shows the result of the age profiles on the risk of migration to the US for both sexes. The values assigned to age intervals are slopes of a curve describing the influence of the age profile on the risk of migration to the US.

Positive values indicate an increase risk of migration during this age span while a negative slope denotes a decreasing risk.

The values of table 1 are summarized in figure 2.

For males there is an increased risk of migration until the age of 18.4 A decrease follows in the next nine years, followed by a second less pronounced decline. For females the risk increases until the age of 16, then a slight decline is seen until 25, when a more pronounced decline is found. At all ages the male curve is distinctively above the female; indicating a greater propensity of male migration. The female slower decline between ages 16 and 25 suggests a wider range for the age preference for migration. Opposed the migration of males is mainly concentrated around the age of 18.

Education

The hypothesis of neoclassical economics on migration predicts that migrants move to places where their skills and abilities are rewarded the most. The training and knowledge acquired in the Mexican educational system is not completely transferable to the United States. Due to differences in language and culture, education received in Mexico is more likely to be rewarded within the country than in the US. The probability of migrating should then decrease as educational level rises. In the study of Zahniser (1999), the only neoclassical hypotheses consistently satisfied are those concerning the effects of human capital. The finding is a negative selection for undocumented migrants with respect to educational attainment. Once in the United States, many highly educated migrants find themselves working in similar types of jobs as less educated migrants. Thus, school provides a mobility ladder constituting a realistic alternative to out-migration and lowering the odds of movement (Massey and Espinosa, 1997).

Appleyard (1999) presented the distribution by occupational categories in 1990 of Mexicans employed in the US. For males, 71 per cent were employed in low skill labors: machine operators, craft jobs, transport, farming and other jobs. Non-manual occupations, including school attendance, accounted for 13 per cent and the unemployed or out of labor market group consisted of 16 per cent. For females the numbers in these same categories were 32 per cent in low skilled employment, 19 per cent in non-manual work and 49 per cent unemployed.

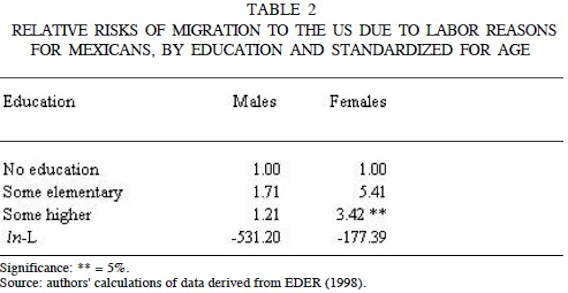

In formulas (2) and (3) we include the education factor and the corresponding coefficient, represented as a piecewise constant per levels of education: no experience of education (which is the base level), being or having finished/ stopped elementary education and being or having finished/stopped junior high or further education.5 The results of the new factor in the hazard model are presented in table 2.

The risks of migration, associated with the different levels of education, are given relative to persons having no education. For males, the highest risk of migration is found for persons with some elementary but no higher education. Males with some experience of higher education are in between those having only elementary education and the reference group. As already seen in the distribution by occupation categories education is not needed for most of the occupations that Mexican males typically hold in the US.

The female pattern is similar to that found for males. The only difference between the sexes is the higher relative risk found for females with any kind of education. Women with any experience of higher education are significantly more inclined to migrate than women with no education. This is also supported by the percentages presented by Appleyard. Among the women who are active in the US labor market the difference in proportions between low skilled and non-manual workers is smaller than for males, suggesting a higher positive role of education for females.6 Table 2 and the rest of the tables in the article only include the factor of interest in each section although the model includes the previously examined factors. The complete results of the models are included in the Appendix.

Family responsibilities

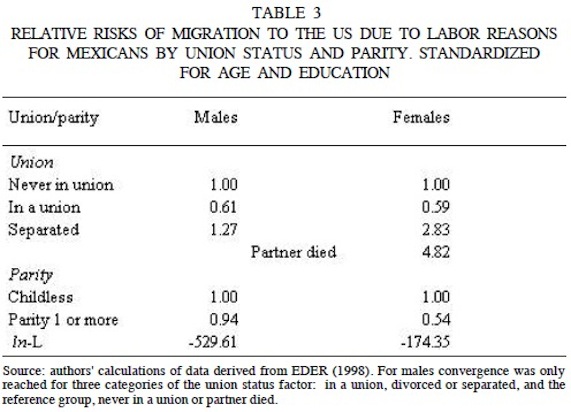

Family responsibilities influence the migration decision in different directions. Zahniser (1999) hypothesizes that the migration decisions of married individuals are influenced by their desire to spend time with their spouse. A couple also mitigate the economic necessity, which my lead to migration, by their common labor power. On the other hand, the presence of children may impose economic pressure, and one way of getting a higher income is to work in the United States. To account for family responsibilities two factors are incorporated in this section. One accounts for the union status of the individual, and the other for the number of children. Table 3 shows the results for these two terms in the model.

Comparing the risk of migration for persons with one or more children, to those without any children, we see a clear gender difference. Females with children have almost half the risk of migrating compared to those without any children. Opposite, men with or without children have almost the same propensity to migrate.

In table 3, the impact of the different levels of union status are displayed. For males, only three levels are used due to convergence problems of the model.7

The decrease in the risk of migration due to being in a union is similar for women and for men, around 40 per cent lower than for the reference group of persons never in a union. For women becoming separated or whose partner dies the risk of migration increases with respect to the never partnered women. Separation for males also increases their risk of migration slightly compared to the reference group.

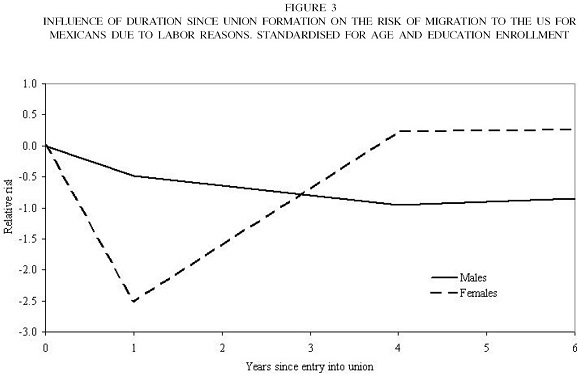

The time at which a person enters a union could be a decisive moment for migration. We could hypothesize that this would affect the risk of migration either by causing an increase, for example a woman that enters a union with a man who is already settled in the US and then joins him. A decrease could also be a consequence, for example for a man that wants to spend more time with his partner in Mexico. To access the impact of union duration on the risk of migration a new hazard model starts at the moment when the person initializes a union. Figure 3 shows the results of this model.

For both males and females, there is a decrease in migration propensities in the first year after entry into a union, more accentuated for women. An increase is found for females after the first year which leads the married females to reach and exceed the level which they experienced before entering a union. This supports the thesis of family reunification, mentioned in the gender section, some years after the union formation.

Network

A migration network can broadly be defined as any socioeconomic link between the origin and destination of a prospective migrant that facilitates migration between the two points. The literature points to networks as having a strongly positive influence on the probability of international migration by reducing the costs of migrate and limiting its associated risks (Zahniser, 1999 and Massey, 1987). Zahniser lists some of the ways in which family and friends help the new Mexico-US migrant: by accompanying the first-time migrant to border-crossing staging areas; transferring experience on negotiating with coyotes8 and on rules in case one gets apprehended by the border police; by providing an initial place to stay at little or no costs, and helping with the search for work (in some cases, the migrant is even able to secure employment in the US prior to arrival). In other words, the presence of family and friends in the United States can make life north of the border easier. For this reason, migration networks should increase the probability of migrating.

Social capital theory describes a direct connection between networks and the costs and benefits of migration, and it emphasizes the recursive nature of the network formation. As a result of the increased benefits and reduced costs and risks of having a network some people decide to migrate. This extends the set of people with ties to the destination area, which, in turn, lowers the costs and risks and raises the benefits for a new set of people, causing some of them to migrate, and so on (Massey and Espinosa, 1997).

Yang (1998) elaborates an examination of the visa application records to enter the US. This data reveals that the category which dominated the demand for immigration consisted of brothers and sisters of US citizens and their spouses and children. Following this finding we add a new factor in our model that accounts for the presence of siblings9 in the US. The results of including this factor are shown in table 4.

The remarkable importance of the presence of siblings in the US is seen in several ways in table 4. The high relative risk of migration influenced by the presence of siblings in the US, compared to those who do not have siblings, is evident in the relative risks for both sexes, but stronger for females. We also note that the model as a whole is improved more than by adding any other factor. This can be seen by comparing the log-likelihood line In-L of tables 3 and 4. A last indicator is the 1 per cent statistical significance achieved by our factor of presence of siblings in US. As shown by Cerrutti and Massey (2001), family considerations are often present in the initiation of female migration. Females often become international migrants by following a family member or their husbands. Men are often introduced to the migration experience through a family member but can also migrate independently. Table 4 also illustrates the higher family considerations existent for the female migrants.

Period: the peso crisis and illegal migration

The effect of economic inflation and peso devaluation in Mexico is often thought to increase the propensity for Mexicans to migrate due to the increasing relative value of US earnings.

However, not all studies show that there is an immediate and consistent relationship between peso devaluations and illegal immigration to the US. Mexico has experienced major devaluations at the end of each of the last presidencies. Devaluations took place in 1976, in 1982-1883, again in 1986-1988, and in 1994-95 in connection with a rebellion in the south of the country. After the 1982-1983 peso devaluation, it took about sixteen months for the US Border Patrol to notice a significant increase in illegal immigration (Martin, 1996). In 1987, apprehensions dropped despite a devaluation of the peso mainly because many Mexicans became legalized US immigrants. The peso crises may actually have a negative effect on the probability of undocumented migrants because they drive up the cost of surreptitious border crossing, a cost that must be paid in dollars (Massey and Espinosa, 1997). On the first of January 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect, stimulating economic and job growth throughout North America. Martin (1996) shows that not even this improvement of economic transactions and foreign exchange tended to affect the migration patterns.

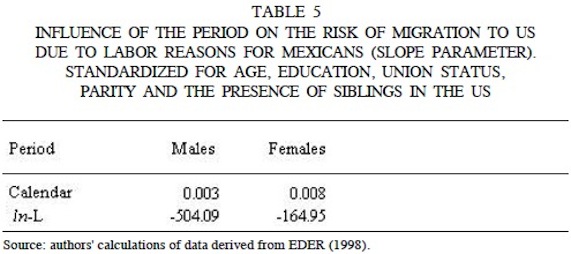

We implemented several models to test any period effect, but little change was found. Table 5 shows the results of the most parsimonious model.10

Males and females have an increase in the risk of migration over time. This is more accentuated for women,11 which supports the idea of an increased female share in international migration. These results are also confirmed by other studies, by already mentioned authors, where it was found that neither the peso crisis nor the NAFTA agreement changed the pattern of migration.

Labor status

Labor market theory predicts that undocumented migration is fomented by the US labor demand. An increase in the US employment growth rate tends to be followed by an increase in the likelihood of illegal migration, suggesting that Mexicans do, in fact, respond to labor market opportunities when they decide to migrate to the US (Martin, 1996).

Whether influenced by the US labor market or not, migrants, the family, or the community somehow compare the benefits of migrating with staying in the community. As pointed out by Massey and Garcia (1987), the net return of international migration is influenced by several factors, concerning employment and earning probabilities. The inputs in Massey and Garcia's formula are obtained through the existence of networks or from own knowledge. Such knowledge is improved by the duration of the potential migrant's labor experience in Mexico.

The last characteristic added to formula (1) is the influence of the labor status in Mexico on the risk of migration to the US. As shown in figure 1, the transition from working in Mexico to working in the US can occur from: never worked, working, or unemployed in Mexico. Table 6 shows the relative risk of migration for individuals in these categories.

Working males reduced their risk of migrating with 40 per cent when being employed compared to those which have never worked. Opposite, women working increased their risk of migrating by more than double compared to those which had never worked. Unemployed men had an increase of 33 per cent where females increased their risk more than four times as compared to persons which have never worked.

The decision to migrate depends on the labor status of the person, but also on the time since the person was employed. To measure this, we study the duration since the potential migrant initialized his or her labor experience. Duration since first employment is included in the model as a duration spline.12 Figure 4 shows the results of the model including this factor.

Females experience a slow increase in the risk of migration after they have started working and this increase does not change over time. This is in contrast to males, where a strong decrease is found in the risk of migration during the first year after initializing work. During the time from one to three years in the labor market the risk of migrating increases for males. The increase continues after three years but with a less pronounced slope. These patterns are obtained for the working population. The gender distribution in the Mexican labor force implies that many women are occupied with domestic activities which are not considered as a working category. The females found in our working group are therefore probably over-represented by highly skilled women. As already seen when looking at the education factor, highly skilled women have an increased propensity to migrate compared to non-skilled females.

An application: ageing, working and marrying

Lillard and Panis (1998) suggest an alternative way of summarizing all the splines that we have calculated. They created life histories of idealized persons and added all known information in a curve of relative risks that depended on all their time-varying characteristics.

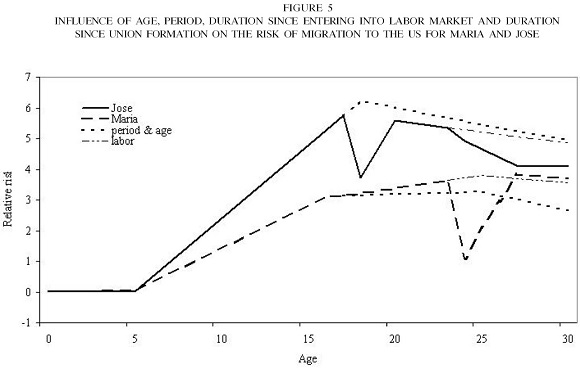

Two Mexicans are here used to simulate the potential Mexican migrants: María and José. These two fictitious persons were born in the same year of 1968, they started working when they were 17 years old in 1985, and married in 1991 when they were 23. Following the results of table 8,13 we can combine the different splines in order to study their impacts on relative risks of migrating to the US. In figure 5, we see the results from the life history of María and José.

The figure includes the patterns of period and age which would have remained if they had not started working or started a union. Also the pattern which would have occurred if they had started working but not entered a union is added.

The two Mexicans each experience a substantial decrease in their risk of migrating to the US. José reduces his probability of migrating when entering into the labor at the age of 17, and a less pronounced second reduction after his marriage at 23. Maria is positively influenced to migrate after 17 when she enters into the labor market but strongly negatively affected by her wedding at the age of 23. The importance of the life event perspective becomes evident in this example where the influencing factors determines the outcome of the migration decision.

Unobserved heterogeneity

Finally we also included into the model a term to measure the absent of factors that would explain the Mexican migration to the US better. As we have seen in the previous sections, Mexican migration to the US is an action of a group with certain characteristics, but some unobserved factors might exist that influence this movement. The new term measures this selection effect not accounted by the previous employed factors. The measurement of the possible selection effect was examined in a model where both sexes were combined.14 The model examining for unobserved heterogeneity did not find any significant impact in the rest of the factors (not shown here). This indicates a good selection of the factors included in the model.

Conclusions

The Mexican temporary migration to the US for working purposes is characterized by a high importance of the presence of networks for the decision of migrating, here demonstrated through the presence of siblings in the US. There is an increase in migration propensities due to a period effect, which every year is influencing more persons to move north of the Mexican border. This increase over time is higher for females than for males, but males make out the greatest share of the Mexican temporary migration to the US. A higher educational level has a positive effect on temporary migration for females, while this effect is much weaker for males: for males only basic education is needed on the job market for Mexican migrants in the US.

Labor status and union formation have a substantial influence on the risk of migration. Our findings suggest that males are strongly negatively influenced to migrate in the period after their first employment, while a strong decrease in female migration is found when they enter a union. The influence of these events on the risk of migration decreases with time since the corresponding event started. The study by Cerruti and Massey (2001) suggests that females are mainly motivated to migrate for family reasons, while males mainly migrate for reasons of employment. Our study confirms the importance of the labor status for males, and the union status for females. The contribution of the present article is the highly relevant analysis of the impact by duration since entering into labor market or a union. Therefore, using the methodology applied here allows us to detect changes over time of the influence of labor status and union status on the risk of migrating to the US.

Our results emphasize the importance of differentiating between genders in any study on migration. Our estimates do not represent the true probabilities of total migration, because the study populations only consist of persons who were living in Mexico in 1998. This implies that all the migrants identified in our study are persons who have migrated to the US and later returned to Mexico. Nevertheless, with this research we contribute with a further step in the understanding and interpretation of the social processes involved in international migration by including the dynamics of time-varying factors.

Reference

Appleyard, R., 1999, "Emigration dynamics in developing countries", in vol. III, Central America and the Carribean, Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Aldershot, England. [ Links ]

Cerrutti, M. and D. Massey, 2001, "On the auspices of female migration from Mexico to the United States", in Demography 38(2). [ Links ]

Cornelius, W.A. and A. Marcelli Enrico, 2000, "The changing profile of Mexican migrants to the United States: new evidence from California and Mexico", in IZA Discussion paper núm. 220, http://www.iza.org/ [ Links ]

Donato, K. and S.M. Kanaiaupuni, 2000, "Poverty, demographic change, and the migration of Mexican women to the US", in Women's position and demographic change, edited by Federici, N, Mason, KO, Sogner, S. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

EDER, National Retrospective demographic survey , 1998, in http://www.gda.itesm.mx/cee/eder/ México. [ Links ]

García and M. Griego, 1988, "Migración internacional", in Demos núm. 1, México. [ Links ]

Lillard, L.A. and C.W.A. Panis, 1998, aML: multilevel multiprocess modeling; release 1, user's guide and reference manual, EconWare, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Martin, P., 1996, "Effects of NAFTA on labour migration", in International trade and migration in the APEC region, edited by Lloyd, PJ, Williams, LS. Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Massey, D.S. et al., 1998, World in Motion-Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium, Clarendon Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Massey, D.S. and K.E. Espinosa, 1997, "What is driving Mexico-US migration? A theoretical, empirical and policy analysis", in American Journal of Sociology núm. 102. [ Links ]

Massey, D.S. and F. García España, 1987, "The social process of international migration", in Science núm. 237. [ Links ]

Massey, D.S., 1987, "Understanding mexican migration to the United States", in America Journal of Sociology 92(6). [ Links ]

Partida, V., 1998, "Los determinantes demográficos del crecimiento de la población", in Demos 11, México. [ Links ]

Yang, P.Q., 1998, "The demand for immigration to the United States", in Population and Environment 19(4). [ Links ]

Zahniser, S.S., 1999, "One border, two transitions: Mexican migration to the United States as a two-way process", in American Behavioral Scientist 42(9). [ Links ]

1 Persons traveling to the Mexico-US border with the intention of crossing but not achieving it, were also included as sojourners.

2 The survey EDER (1998) does not include the timing of migration for the siblings, only the number of siblings in the US in 1998 are available.

3 Changes in the US immigration law, especially the legalization provisions of the 1986 Immigration and Control Act (IRCA), lead to an increase in migration by women and dependent children.

4 The minimum for the age at which an individual migrated to the US to work is 5. Several other young migrants indicate that it is important to let our initial node start at age five.

5 The six levels of the factor education are here collapsed into three levels.

6 Another way to analyze the effect of education is to study the risk of migration from the time the person started education. This can be done with a spline that sets on when the person gets enrolled into education. Nevertheless, the age at which people are enrolled into education is fixed between 6 and 7 years old, we would here rather be looking at an age effect than of the education factor.

7 The reference group for males is never in a union or who experienced the death of a partner. The problem of convergence of the model is probably due to few numbers of individuals who experienced the death of a partner.

8 Persons that for money help the undocumented migrants to cross the border.

9 Only this category was available in the data, neither parents nor other relatives.

10 The time-varying factor for calendar year is obtained by adding the fixed variable year of birth and the time-varying age.

11 For males, there is a decrease in the influence of the period factor on the risk of migration after 1994. The change occurred at the same time as national events such as the NAFTA agreement, the presidency succession, and the rebellion in the south of Mexico. It could be argued that these national events affected the migration pattern, but it could also be a false effect of the period, due to many temporary migrants still being in the US at the time of interview, who were therefore not found in the survey.

12 The interest is here to study the decision of migrating depending on the duration since the first working experience. The model also includes individuals that became unemployed after some time of working.

13 The complete model is found as model 8 in the appendix.

14 Letting Ui represent the unobserved heterogeneity, this is implemented in the hazard model through a univariate normal-distributed residual.