Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana

versão impressa ISSN 1405-3322

Bol. Soc. Geol. Mex vol.62 no.3 Ciudad de México Dez. 2010

Artículos

Evaporite mineralogy and major element geochemistry as tools for palaeoclimatic investigations in arid regions: A synthesis

Mineralogía de evaporitas y geoquímica de elementos mayores como herramientas para la investigación paleoclimática en regiones áridas: una síntesis

Werner Smykatz–Kloss1, Priyadarsi D. Roy2,*

1 Institute of Mineralogy and Geochemistry, University of Karlsruhe, 76131, Karlsruhe, Germany.

2 Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, CP 04510, México D.F., México.*E–mail: roy@geologia.unam.mx

Manuscript received: July 3, 2009.

Corrected manuscript received: September 14, 2009.

Manuscript accepted: May 14, 2010.

Abstract

This paper presents a synthesis of the applications of evaporite mineralogy and the relationship between major elements for the palaeoclimatological research of arid regions, with examples from Playa Oum el Krialate in Tunisia, Wadi Natron in Egypt, East African Rift Valley, etc. The numerous evaporite minerals serving as indicators of palaeo–drylands (salinity and evaporation) include carbonates, sulfates, and Na, K, Ca, and Mg chlorides. The occurrence of double salts, such as glauberite, carnallite, kainite, gaylussite, pirssonite, burkeite, etc., suggests disequilibrium conditions. Apart from that, the presence of very rare Fe–sulfates, such as rozenite and szomolnokite, indicates anoxic conditions with higher salinity. The formation of Na–silicates, such as magadiite and kenyaite, implies a decrease in pH of a highly alkaline Na concentrated brine. The Mg–silicates (palygorskite, Mg–montmorillonite and talc) form quickly and then re–dissolve when conditions change. Identification of fulgurites in the Sahara has been related to palaeo–lightning. We have also discussed a simple geochemical approach of using the ratios of soluble/insoluble elements to identify palaeo–arid events with examples from loess–soil sequences from Feiran Oasis in the Sinai Desert (Egypt) and salty silt lacustrine sequences from Thar Desert (India).

Keywords: Tropical deserts, evaporite minerals, geochemistry, synthesis.

Resumen

En este trabajo se presenta una síntesis del uso de minerales evaporíticos y relaciones entre elementos mayores en investigaciones paleo–ambientales de zonas áridas, con ejemplos de la sabkha Oum el Krialate en Túnez, Wadi Natron en Egipto, Valle de Rift del África oriental, etc. Los minerales evaporíticos indicadores de eventos secos (salinidad y evaporación) son carbonatos, sulfatos y cloruros de Na, K, Ca y Mg. La ocurrencia de sales dobles, como glauberita, carnalita, kainita, gaylusita, pirssonita, burkeita, etc., sugiere condiciones de desequilibrio. Además, la presencia de sulfatos de Fe poco comunes, como rozenita y szomolnokita, indica condiciones de anoxia con alta salinidad. La precipitación de silicatos de Na, como magadiita y kenyaita, implica la dilución de una salmuera muy alcalina y con alta concentración de Na. Los silicatos de Mg (paligorskita, Mg–montmorillonita y talco) precipitan rápidamente para disolverse nuevamente al cambiar las condiciones. La presencia de fulguritas en el Sáhara indica la incidencia de paleo–relámpagos. Asimismo, para identificar eventos de paleo–sequía, se discute un método sencillo basado en relaciones de elementos solubles e insolubles con ejemplos de secuencias de suelo tipo loess del Oasis de Feirán (Desierto de Sinaí, Egipto) y de secuencias de sedimentos lacustres del Desierto de Thar (India).

Palabras clave: Desiertos tropicales, minerales evaporíticos, geoquímica, síntesis.

1. Introduction

The study of (palaeo–) climatic registers is highly effective in reconstructing the past climate and other conditions present at the time of sediment formation or deposition. The knowledge of old climates and the mechanisms of climatic changes may help to identify the regularities of palaeoclimatology and could possibly lead to improve present–day agriculture and horticulture as well as the management of water, soil, and natural resources. While marine sediments on continents demand a transgressive sea, the sediments in lagoonal or even in true sabkha environments require a topographically closed basin and fluvial freshwater input. After some time, these lakes become saline in (semi–) arid environments and finally evaporate in pans, accompanied by sedimentation caused by aeolian activity and erosion, e.g. dune and loess formation, grain sorting, and formation of fluvial and lake terraces. The criteria used to recognize these geomorphological formations and processes in old sediments and soils have been treated in hundreds of geomorphological and geological articles and textbooks (e.g., Glennie, 1970; Holser, 1979; Büdel, 1982; Goudie and Pye, 1983; Lowe and Walker, 1984; Gasse et al., 1987; Thomas, 1989; Summerfield, 1991; Thomas and Shaw, 1991; Cooke et al., 1993; Kröpelin, 1993; Goudie and Wells, 1995; Lancaster, 1995; Williams and Balling, 1996; Dittmann, 1999; Glennie and Singhvi, 2002).

Diagenetic processes change the association of primary minerals (at least partly). Evaporite minerals (salts) are dissolved and transported in solution until more stable products precipitate. Physical and chemical conditions determine the transformation of salts (Braitsch, 1971; Busson and Perthuisot, 1977; Eugster and Hardie, 1978; Holser, 1979; Usdowski and Dietzel, 1998). But quite often, the development from primary limnic formations to secondary transformed products can be traced back using remnants or relict structures (Wiedemann and Smykatz–Kloss, 1981). Sophisticated physical methods may answer some questions, e.g. the determination of isotopic ratios of C, S, O, B, Sr, or H (see Hoefs, 1987; Heine, 1998; von Grafenstein et al., 1998; Eitel, 2000), including age determinations by 14C methods (Geyh and Jäkel, 1974; Yadav, 1997; Geyh, 2005). Even in case of lack or absence of organic material, electron spin resonance (ESR) (Dhir et al., 2004), thermoluminescence (TL) or optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) methods may help (Rögner et al., 1999; Eitel et al., 2004), provided that the tolerance of the method is suitable to solve a certain problem (Zöller, 1995; Jäkel, 2004). Considering the peculiarities in formation and dissolution behaviour of salt or clay minerals, a certain reconstruction of a primary limnic environment is possible. Both the degree of interaction between sediments (or soils) and water and the development of secondary products are dependent on several environmental conditions, namely temperature, pH and Eh values, pressure, activity of water and ions, soil and sediment porosity and packing density, solubility of species and interfering (disturbing) compounds, equilibrium or disequilibrium conditions, and time.

2. Preliminary remarks on geomorphology, geology, biology, physics, and regional distribution

2.1. Geomorphological criteria

The formation of terraces by lake and sea level fluctuations is a widely observed geomorphological phenomenon (Büdel, 1982; Rust, 1989; Vogel, 1989; Heine, 1990). Similarly, palaeo–dunes are indicators of wind directions or variations in past wind currents (Bowler, 1973; Sarnthein, 1978; Lancaster, 1981; Wasson et al., 1983, 1984; Gaylord, 1990; Kar, 1990; Pye and Tsoar, 1990; Felix–Henningsen, 2000, 2004; Grunert et al., 2000; Grunert and Lehmkuhl, 2004; Heine, 2004). Lake and sea level fluctuations mirror past changes in precipitation as well as marine transgressions and regressions due to climatic and tectonic activities (Faure and Elouard, 1967; Nir, 1974; Perthuisot, 1976; Gasse et al., 1987; Tooley and Shennan, 1987; Koessl, 1988; Lancaster, 1989; Baumhauer, 1990; Baumhauer et al., 2004; Fang, 1991; Wenigwieser, 1992; Qin and Yu, 1998; Wünnemann et al., 1998; Eitel et al., 2004; Sinha and Raymahashay, 2004; Sinha et al., 2006; Roy et al., 2006, 2008a, 2009; Achyuthan et al., 2007). Increasing aridity leads to salt evaporation in pans and playas (Lancaster, 1981; Petit–Maire, 1986; Goudie and Wells, 1995; Eitel and Blümel, 1997; Schütt, 1998, 2004; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1999/2000) and enables loess and silt accumulation (Sirocko and Sarnthein, 1989; Vogel, 1989; Derbyshire et al., 1995; Gallet et al., 1996; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1998; Brunotte and Sander, 2000; Grunert and Lehmkuhl, 2004; Singhvi and Kar, 2004). Special conditions are required for the formation of fulgurites as observed by Sponholz et al. (1993) in the Sahara. The presence of fulgurites demonstrates the interaction of lightning and lake surfaces.

2.2. Geological and biological criteria

Climatic changes are also mirrored in geological, sedimentological, and biological events (Tricart and Cailleux, 1972; Carbonel et al., 1988; Sirocko and Sarnthein, 1989; Vogel, 1989; Geyh and Eitel, 1998; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1998; Heine and Heine, 2002; Jain and Tandon, 2003; Mischke et al., 2004). The organic carbon content on the continental slope of the Arabian Sea (Indian Ocean) tells of palaeoclimatic changes and monsoon development in the adjacent continents (Berner and Lasaga, 1989; Sirocko, 1995). Sea level fluctuations show global climatic changes as well (Faure and Elouard, 1967; Einsele et al., 1974). Geophysical methods also contribute (Schumm, 1977; Prell and Kutzbach, 1987) and astronomic theories, like Milankovitch's, have led to the explanation of climatic changes (Berger and Tricot, 1986; Blum and Törnquist, 2000).

Biological aspects may play an important role in reconstructing palaeontologic developments (Maley, 1983; Gasse et al., 1987; Schulz, 1987). The development of ostracod and diatom species, in particular, has been used for palaeoenvironment reconstructions (Carbonel et al., 1988; Caballero, 1997; Mezquita et al., 1999; Palacios Fest et al., 2002; Mischke et al., 2004; Caballero et al., 2005).

2.3. Physical and chemical criteria

The influence of ice and ice transport on rocky grounds and soils may be mentioned briefly. This includes all physical processes, such as freezing and thawing, and those processes related to glaciers, wind, and thunderstorms, as well as the formation of (peri–) glacial and structured soils etc. (Fink and Kukla, 1977; Washburn, 1979; Büdel, 1982; Harris, 1986; Tyson, 1986). Roberts and Spencer (1995) and Spencer et al. (2003) used fluid inclusions in halite (evaporitic crusts in Death Valley, California) for the measurement of palaeotemperature. When available, the exact methods of physical dating and isotope geochemistry are very helpful in fixing palaeoclimatic events and changes (Geyh and Jäkel, 1974; Delibrias et al., 1976; Gasse et al., 1987; Heine, 1990; Yadav, 1997; Geyh and Eitel, 1998; Hofmann and Geyh, 1998; von Grafenstein et al., 1998; Dutkiewicz et al., 2000; Glennie and Singhvi, 2002; Juyal et al., 2003). Isotopic ratios may characterize palaeoenvironments (Hoefs, 1987; Tyson, 1986; Sharp, 2007). The concentration of total organic carbon (TOC) represents the amount of organic matter preserved after sedimentation, which depends upon initial production and the degree of degradation (Meyers and Teranes, 2001; Leng et al., 2005). The source of organic matter can be differentiated by the ratio of organic carbon and total nitrogen (C/N) and δ13C. Organic matter derived from lacustrine phytoplankton has a lower C/N (<10) value compared to organic matter derived from terrestrial plants (>10) (Prasad et al., 1997). δ13C of organic matter indicates the source of HCO3– and dissolved CO2 (i.e. derived from C4 or C3 plants by ground water inflow, organic matter deposited as methane in the lake bottom, catchment carbonate deposits, and atmospheric CO2). Similarly, δ18O in inorganic material (carbonates and silicates) indicates palaeo–temperature during formation of the mineral phases (Leng et al., 2005). In water samples, deviation of both δ18O and δD from the Global Meteroric Water Line suggests kinetic fractionation due to evaporation. In warmer and tropical water, both isotopes have higher δ values compared to colder and polar rainfall (Leng and Marshall, 2004).

Organic material is also used for 14C measurements (Geyh, 2005) to reconstruct the chronology of the identified events. In the absence of organic material, which is the case in many Quaternary and even Tertiary arid environments, luminescence (TL, OSL) (Zöller, 1995; Rögner et al., 1999) or ESR techniques (Dhir et al., 2004) may help.

2.4. Regional distribution of drylands

Pans, playas and palaeolakes of the great dryland areas have been the objects of interests in palaeoclimatic studies. In these regions, enrichment of (earth) alkalies, iron and silica are reported. Iron enrichment is documented in (semi–) aridic ferricretes of former swamps (Nahon, 1976; Felix–Henningsen, 2000, 2004). Silica enrichment in highly alkaline lakes is reported for one of the two main silcrete formations (i.e. allochthonous silcrete, while the autochthonous type represents a soil formation) by Summerfield (1983), Young (1985), Joachim (1988) and Thomas and Shaw (1991). Salt enrichment is documented by Derbyshire et al. (1995), Mehrshabi et al. (2003), and Schütt (2004). Development of soils, pans, and desertic landscape of the world's largest desert, the Sahara, is reported by Petit–Maire (1986, 1987, 1991) and Baumhauer (1990). Guo et al. (2000) have compared the Sahara with east Asian deserts, including the Gobi and other large deserts in China, Tibet, and Mongolia (Kukla, 1987; Fang, 1991; Hofmann, 1993; Derbyshire et al., 1995; Jäkel, 1995; Lehmkuhl, 1995; Liu and Fu, 1996; Qin and Yu, 1998; Wünnemann et al., 1998; Grunert et al., 2000; Grunert and Lehmkuhl, 2004). While the deserts of Iran (Mehrshabi et al., 2003) and Arabia (Glennie and Singhvi, 2002; Barth, 2003) are rarely studied, the Indian Desert (Thar) located in the northwestern Indian state of Rajasthan has received significantly more attention from geoscientists (Wasson et al., 1983, 1984; Kar, 1990; Jain and Tandon, 2003; Juyal et al., 2003; Singhvi and Kar, 2004; Sinha et al., 2006; Roy et al., 2001, 2006, 2008b, 2009). This is also true for the world's oldest desert, the Namib, in South Africa (Rust, 1989; Vogel, 1989; Heine, 1998, 2004; Eitel, 2000; Eitel et al., 2004). Relative to the Namib, a relatively small desert, Sinai in Egypt, has received some attention by Nir (1974), Rögner and Smykatz–Kloss (1991), Rögner et al. (1999, 2004), and Smykatz–Kloss et al. (1998, 1999/2000, 2004). American deserts have been studied by Fahey and Mrose (1962), Bradley and Eugster (1969), Gaylord (1990), Monger and Daugherty (1991), Bischoff et al. (1997), Metcalfe et al. (2002), and Roy et al. (2010). The Australian desert has been studied by Young (1985), Holland et al. (1988), Nanson and Tooth (1989), and English et al. (2001).

3. Mineralogical and geochemical criteria and examples

3.1. Minerals as criteria

Among the common cations, the solution and precipitation behaviour of Na+ and Mg2+ (and Fe2+ and Mn2+ in Eh–negative environments) are very suitable (Holser, 1979, Mason and Moore, 1982). Sodium is generally highly soluble (abundant in water bodies of arid environments) and dissolves even when water activity is low. Suitable environments for preservation of Na+ are (semi–) deserts, e.g. the drylands of Northern Africa as Wadi Natron in Egypt (Wenigwieser, 1992), Playa Oum el Krialate in Tunisia (Perthuisot, 1976; Koessl, 1988), and similar environments in Libya, Morocco, and Mauritania. In these environments, besides halite (NaCl), Na+ precipitates as the highly soluble mirabilite (Na2SO4•10H2O), but only in contact with water (e.g. in pools, see Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1992). After its formation, mirabilite transforms to thenardite (Na2SO4) on contact with air. In the limnic sediments of Wadi Natron, idiomorphic thenardite occurs in crystals with diameters up to a few centimetres.

Among the places where a large number of disequilibrium products occur in a short period, the Playa Oum el Krialate is one of the most favourable and well–studied localities. A short period spans a few weeks up to a few months, until the next rain occurs and dissolves the Na–salts. But during dry periods, i.e. times of low water activity, a number of semi–finished products ("precursors") are observed, even locally as main constituents, many of which contain either very little water or no water at all. These are in the process of becoming thermodynamically reasonable and stable end products and minerals such as mirabilite (Na2SO4•10H2O), hexahydrite (MgSO4•6H2O), pentahydrite (MgSO4•5H2O), leonhardtite (MgSO4•H2O), nahcolite (NaHCO3), trona (Na3(CO3)(HCO3)•2H2O), pirssonite (Na2Ca(CO3)2•2H2O), gaylussite (Na2Ca(CO3)2•5H2O), or burkeite (Na6(CO3)(SO4)2) (see Table 1).

Among these evaporites that partially occur as main constituents, some are very rare compounds and occur as traces, i.e. glauberite, polyhalite, carnallite, bassanite, rozenite and szomolnokite (Spencer et al., 2003) (see Table 1). Bassanite has been found in aridic soils by Akopodje (1985) and Smykatz–Kloss et al. (1985) on the surface of sunny walls in South Tunisia. Very recently, this mineral has been observed as a main component on the ground of the "White Desert" in Egypt, where it is mainly covered by a few centimetres of wind–blown carbonates and anhydrite. This cover of wind–blown weathering products is the reason for the occurrence and longer persistence of bassanite.

The very rare and instable Fe2+–sulfates rozenite and szomolnikite (FeSO4•4H2O and FeSO4•H2O, respectively) are found on the way from the gypsum karst, east of Tatahouine, to the Oum el Krialate playa, associated with organic material (Koessl, 1988; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1992). The preservation of organic material is the reason for the negative Eh environment, which is necessary for forming Fe2+–sulfates. However, the occurrence of bassanite, rozenite, and szomolnokite in the deserts of Egypt and Tunisia is exceptional among sulfate evaporites, as their occurrence requires some shelter from the (rarely abundant) rain events.

Most of the other evaporites are double salts (i.e. combinations of Na, Mg, Ca, and K; see Table 1). These occur only for short periods and in traces; such is the case for glauberite, kainite, carnallite, polyhalite (Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1992), burkeite, trona, pirssonite, and gaylussite (Fahey and Mrose, 1962; Bradley and Eugster, 1969; Holser, 1979). Trona has been a known mineral to Humanity for millennia, conspicuous in the sediments of the Wadi Natron in Egypt (Wenigwieser, 1992).

There is another special tropical environment for the preservation of Na–minerals, co–precipitated with silica, although only when very high amounts of Na and Si in the brine. Such is the case along the East African Rift Valley (East African Graben), e.g. in Kenya and Tanzania, and especially where high temperature and weathering rates of abundant sodic volcanics (Na–carbonatites) feed the playa lakes, such as Lake Magadi and other highly alkaline lakes (pH ~ 12) in the grabens. The alkali (Na) silicates precipitate from oversaturated brines diluted by rain water. The product is magadiite (NaSi7O13(OH)3•3H2O; see Eugster, 1969), that forms only in highly alkaline environments (e.g. Lake Magadi, with pH = 12 and concentrations of Na >100000 ppm). As pH decreases (i.e. by dilution with rain water), magadiite transforms to kenyaite (NaSi11O26.5(OH)4•3H2O) and finally to chalcedony (SiO2) (Eugster, 1969). The formation of magadiite is also reported from a few other (similar) localities in California.

The other highly soluble cation, Mg2+, forms evaporites in very special (semi–) aridic environments, and such Mg–bearing evaporites are somewhat more stable than the Na–bearing ones. Mg2+ compounds occur periodically (e.g., during evaporation in Mg–containing playa lakes) in recent playa lakes in Spain (de la Peña et al., 1982; Ordóñez et al., 1994) and Tunisia (Koessl, 1988) as Mg sulfates of the kieserite–epsomite series (Table 1), and form very soluble intermediate products such as hexahydrite (MgSO4•6H2O), pentahydrite (MgSO4•5H2O) or leonhardtite (MgSO4•4H2O). These minerals are found as efflorescences on dolomitic limestones in Libya as well, together with bloedite in half caves (with stalactites and flowstones) of the Jabal Nafusah (Tripolitania; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1992). The next rain dissolves these products rather quickly, unless they are covered with sediments or other authigenic formations.

There are a few more persisting evaporates of this soluble cation. There are Mg–silicates that form even in contact with water, in playa lakes and sabkha environments. This includes the occurrence of palygorskite ((Mg,Al)2(OH/SiO10)•4H2O) (Millot, 1964; Yaalon and Wieder, 1976; Singer, 1979, 1984; Monger and Daugherty, 1991; Eitel, 1994), Mg–montmorillonite, (Mg3–x(OH)2Si4O10 xAlx•nH2O, Na2–x) (Stengele and Smykatz–Kloss, 1995), or talc (Mg3(OH)2Si4O10) in special cases (mainly metasomatically formed). These minerals form more quickly and re–dissolve when the environmental conditions change. Thus, they represent remnants of the former arid history of that special limnic sediment (Eitel, 1994; Eitel and Zöller, 1996).

More common than simple Na– or Mg– minerals is the case of double salts (like bloedite) (Braitsch, 1971; Koessl, 1988) and carbonates. Sedimentary dolomites are reported from playa lakes in Russia, China, India, North Africa (Roy et al., 2001, 2006). Meta–stable proto–dolomite (Ca>Mg) typically occurs instead of dolomite in limnic and aridic regions (Smykatz–Kloss and Goebelbecker, 1992), where small amounts of Fe and Mn are incorporated into the dolomite structure (Roy et al., 2009).

3.2. Geochemical criteria

The behaviour of highly soluble elements like Na+, Mg2+ (or K+) is contrary to that of hydrolysates, i.e. Ti4+, Al3+, Fe3+ (Mason and Moore, 1982), which are resistant to normal weathering solutions. In contact with water, the soluble elements dissolve and are transported away, while the hydrolysates (interacting with solutions) become increasingly enriched in the sediment. Due to its relatively larger ionic radius and partial immobility, the behaviour of the soluble cation K+ is different. It dissolves (like Na+) but is adsorbed quickly, forming new compounds (e.g. illite) (Reheis, 1990; Pandarinath et al., 1999). Thus, Na/K continuously decreases with time. However, the ratios Na/Ti, Na/Al, Na/Fe, Mg/Al, Mg/Ti, and Mg/Fe (the last three, only in carbonate–free environments) strongly decrease with increasing water activity (and vice versa). Nesbitt and Young (1982) were pioneers in the use of such ratios for palaeoclimatic considerations. Other authors continued in characterising palaeoclimatic environments by using some of these relations (Sirocko, 1995; Gallet et al., 1996; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1998, 2004; Rögner et al., 2004; Schütt, 2004; Roy et al., 2006, 2008b, 2009; Sinha et al., 2006).

Sponholz et al. (1993) observed intermittence between palaeoclimatic events in desert lakes and surrounding geomorphology (e.g., the water level of these lakes) when they identified relics of fulgurites (concretions in the Sahara sand produced by lightnings at former lake levels), which enabled them to reconstruct the desert lake level with time. Similarly, Roy and Smykatz–Kloss (2007) studied the REE geochemistry of evaporites and the degree of roundness of rock fragments in the clastic fractions of sediments in order to reconstruct the palaeo–fluvial conditions in the Thar Desert. Fromm et al. (2005) used Fe–Mn vein mineralisations and the different stages of calcrete formation as indicators of the development of the Tunisian desert. Roy et al. (2009, 2010) used geochemical signatures of chemical weathering and mineralogical composition of playa lake sediments to reconstruct late Holocene hydrological changes at the margins of the Thar Desert (India) and late Pleistocene–Holocene palaeo–environmental conditions at Sonora Desert (Mexico).

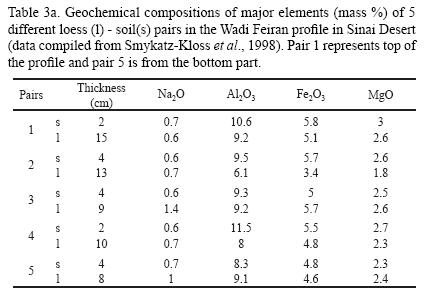

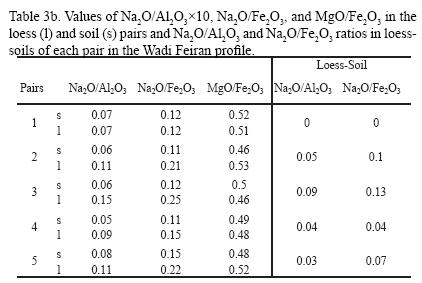

Impressive walls (up to 60 m high) of loess–like sediments are found in the Feiran Valley (Sinai, Egypt) (Nir, 1974; Rögner and Smykatz–Kloss, 1991; Rögner et al., 1999, 2004; Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1999/2000, 2003, 2004). Their origin has been related to fluvial terraces (Büdel, 1982), lake sediments (Nir, 1974), flood products, fluvial–torrential sediments, and alluvial loess (Rögner et al., 2004). The sequences consist of 3–20 cm thick loess layers intercalated with 2–8 cm thick polygonal soil layers. Table 2 presents the geochemical composition of 17 different loess–soil pairs found throughout several metres in a profile from the Feiran Oasis (data compiled from Knabe, 2000, and Rögner et al., 2004). The palaeoecological information is provided by the simple ideas that (1) loessian material is a product of desertic environment, and (2) subsequent soil formation requires water (humidity).

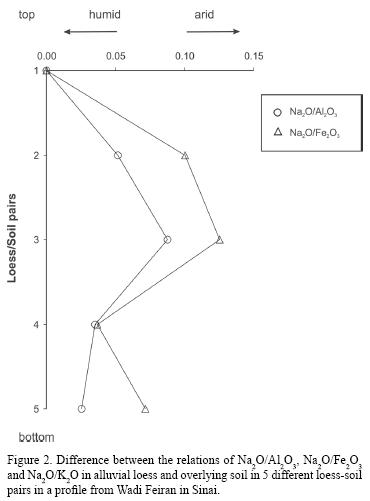

In each loess layer, the weathering of clastic minerals present in the uppermost part (feldspars, micas and, to a lesser degree, amphiboles and pyroxenes) led to the formation of the overlying soil. During this process, dissolution and transportation (i.e. removal) of soluble elements (Na, Mg, and K) occurs in the uppermost part of each loess layer and thus changes the ratios of soluble to (relatively insoluble) hydrolysate (TiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3) elements in the soil. Humid conditions lower these ratios and increasing humidity (or intensive contact of water and loess) is mirrored by an increase in the differences of the mentioned ratios (e.g., amount of Na2O/TiO2 in loess minus the amount of Na2O/TiO2 in the overlying soil). These values are listed in Table 2 and shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows two distinct shifts to very arid conditions (the 7th and 15th loess–soil pairs) and three smaller deviations to (semi–) aridity (the 4th, 12th, and 17th loess–soil pairs). Exact age determinations for these arid events are most desirable. The TL age (Rögner et al., 1999) suggests that the studied profile covers 25.7 ± 3.9 ka and more than 25 m of the profile is unexposed.

Five different loess–soil pairs from the Wadi Feiran profile (Table 3) are quite similar to those of the 17 different loess–soil pairs from Feiran Oasis (Figure1) and represent another profile in the same valley. The chemical compositions (Table 3) show that the soils are mostly enriched in Fe2O3 and Al2O3 compared to the underlying loess. The MgO contents seem to be quite constant throughout the profile. Based on the difference in the ratio between soluble and insoluble elements, two distinct aridic events were identified (Figure 2), i.e. the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th loess–soil pairs. Both these examples show the use of geochemical ratios in identifying arid events in the profiles of alluvial loess near the Feiran Oasis (Smykatz–Kloss et al., 1998; Knabe, 2000; Rögner et al., 2004). Two more examples of the application of geochemical ratios are given below, representing the relations in the playa lakes of the Thar Desert (Roy et al., 2006, 2008b). Table 4 presents the geochemical compositions in the zones (I: 0–10 cm, II: 10–130 cm, III: 130–150 cm) in a shallow profile from the Pachapadra playa lake (Roy et al., 2008b). The last example compares the geochemical relations between a semi–humid (desert margin) Sambhar playa and semi–arid Didwana playa (Figure 3 and Table 5).

4. Conclusions

This paper stresses the applicability of mineralogical and geochemical methods for characterising palaeoclimatological environments in tropical regions, especially in arid environments that lack preservation of biological proxies such as pollen, diatoms, and ostracods. Mineralogically, the persistence of (rare) Na– and (more common) Mg–evaporite minerals may prove the development of a former playa lake (via evaporation and transformation to more stable mineral products in the evaporitic crusts and hardpans). Transformed products, like Mg–salts or Na–, Mg–silicates such as magadiite, kenyaite, and palygorskite are reported from various palaeo–lakes.

Geochemically, the alteration of limnic sediments (e.g., alluvial loess in the Sinai and salty silts in the Thar) and formation of a soil cover by weathering of the underlying layer in contact with water suggest a shift from arid to (semi–) humid climate. The intensity of the humidification is observed in the evaluated differences in geochemical relations between underlying loess and overlying soils. Especially during the humid period, Na–silicates are dissolved and partly transported and removed, while Al3+, Ti4+, and Fe3+ show to be nearly unaffected. Thus, the ratio of soluble (Na2O) to hydrolysate elements (TiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3) and their comparison report the (hydro–) geochemical development of the soil cover from the underlying loess. In suitable environments, a 14C or luminescence age determination will be desirable, but in many cases the sediments (or soils) lack organic carbon for an exact age determination by 14C method. Similarly, the younger sediments in arid regions are constantly mobilized by wind activity and are partially stripped of their OSL signal to be correctly dated by luminescence methods.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Nadine Smykatz–Kloss and Andy Jones (Stroud, England) for helping in English corrections, and to Maria Tannhäuser (University of Karlsruhe) for helping with the preparation of the manuscript.

References

Achyuthan, H., Kar, A., Eastoe, C., 2007, Late Quaternary–Holocene lake level changes in the eastern margin of the Thar Desert, India: Journal of Paleolimnology, 38, 493–507. [ Links ]

Akopodje, e.g., 1985, The occurrence of bassanite in some Australian arid–zone soils: Chemical Geology, 47, 361–364. [ Links ]

Barth, H.J., 2003, Late Holocene sedimentation processes along the Arabian Gulf coast in the Jubail Area, Saudi Arabia, in Alsharhan, A.S., Wood, W.W., Goudie, A.S., Fowler, A., Abdellatif, E.M. (eds.), Desertification in the Third Millenium: Lisse, The Netherlands, Swet & Zweitlinger Pubishers, 237–244. [ Links ]

Baumhauer, R., 1990, Zur holozänen Klima– und Landschaftsentwicklung in der zentralen Sahara am Beispiel von Fachi Dogomboulo (NE Niger): Berliner Geographische Studien, 30, 35–48. [ Links ]

Baumhauer, R., Schulz, E., Pomel, S., 2004, Environmental changes in the Central Sahara during the Holocene — The Mid–Holocene transition from freshwater lake into sebkha in the Segedim depression, NE Niger, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 31–45. [ Links ]

Berger, A., Tricot, C., 1986, Global climatic changes and astronomical theory of Palaeoclimates, in Cazenave, A. (ed.), Earth Rotation: Solved and Unsolved Problems, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Reidel Publishing Company, 111–129. [ Links ]

Berner, R.A., Lasaga, A.C., 1989, Modeling the geochemical carbon cycle: Scientific American, 260, 54–61. [ Links ]

Bischoff, J.L., Fitz, J.P., Fitzpatrick, J.A., 1997, Responses of sediment geochemistry to climate change in Owens Lake sediment: An 800–k.y. record of saline/fresh cycles in core OL 92: Geological Society of America Special Paper, 317, 165. [ Links ]

Blum, M.D., Törnquist, T.E., 2000, Fluvial responses to climate and sea–level change: a review and look forward: Sedimentology, 47, 2–48 [ Links ]

Bowler, J.M., 1973, Clay dunes: their occurrence, formation and environmental Significance: Earth Science Review, 9, 315–338. [ Links ]

Bradley, W.H., Eugster, H.P., 1969, Geochemistry and paleolimnology of the trona deposits and associated authigenic minerals of the Green River Formation of Wyoming: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper, 496–B, 71. [ Links ]

Braitsch, O., 1971, Salt Deposits. Their Origin and Deposition: Berlin, Springer, 297 p. [ Links ]

Brunotte, E., Sander, H., 2000, Loess accumulation and soil formation in Kaokoland (Northern Namibia) as indicators of Quaternary climatic change: Global and Planetary Change, 26, 67–75. [ Links ]

Büdel, J., 1982, Climatic Geomorphology: Princeton, Princeton University Press, 443 p. [ Links ]

Busson, G., Perthuisot, J.P., 1977, Interet de la sebkha el Melah (Sud Tunisia) pour l'interpretation de series evaporitiques anciennes: Sedimentary Geology, 19, 139–164. [ Links ]

Caballero, M.M., 1997, The last glacial maximum in the basin of Mexico: the diatom record between 34000 and 15000 years BP from Lake Chalco: Quaternary International, 43/44, 125–136. [ Links ]

Caballero, M., Peñalba, M.C., Martínez, M., Ortega–Guerrero, B., Vázquez, L., 2005, A Holocene record from a former coastal lagoon in Bahía Kino, Gulf of California, Mexico: The Holocene, 15, 1236–1244. [ Links ]

Carbonel, P., Colin, J.P., Danielopol, D.L., Löffler, H., Neustrueva, I., 1988, Palaeoecology of limnic ostracods: A review of some major topics: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 62, 413–461. [ Links ]

Cooke, R.U., Warren, A., Goudie, A.S., 1993, Desert Geomorphology: London, UCL Press, 526 p. [ Links ]

de la Peña, J.A., García–Ruiz, J.M., Marfil, R., Prieto, M., 1982, Growth features of magnesium and sodium salts in a recent playa lake of La Mancha: Estudios Geológicos, 38, 245–257. [ Links ]

Delibrias, G., Ortlieb, L., Petit–Maire, N., 1976, New 14C data for the Atlantic Sahara (Holocene). Tentative interpretations: Journal of Human Evolution, 5, 535–546. [ Links ]

Derbyshire, E., Kemp, R., Meng, X., 1995, Variations in loess and paleosol properties as indicators of paleoclimatic gradients across the Loess Plateau of North China: Quaternary Science Review, 14, 681–697. [ Links ]

Dhir, J.P., Tandon, S.K., Sareen, B.K., Ramesh, R., Rao, T.K.G., Kailath, A.J., Sharma, N., 2004, Calcretes in the Thar Desert, genesis, chronology and palaeoenvironment, in Singhvi, A.K. (ed.), Quaternary History and Palaeoenvironmental Record of the Thar Desert in India: Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, 113, 473–515. [ Links ]

Dittmann, A., 1999, Paläogeographie und Periphyten: Frankfurter Geowissenschaftliche Arbeiten, D 25, 43–73. [ Links ]

Dutkiewicz, A., Herczeg, A.L., Dighton, J.C., 2000, Past changes to isotopic and solute balances in a continental playa: clues from stable isotopes of lacustrine carbonates: Chemical Geology, 165, 309–329. [ Links ]

Einsele, G., Herm, D., Schwarz, H.U., 1974, Sea level fluctuation during the past 6000 yr at the coast of Mauritania: Quaternary Research, 4, 282–289. [ Links ]

Eitel, B., 1994, Paläoklimaforschung: Pedogener Palygorskit als Leitmineral?: Die Erde, 125, 171–179 [ Links ]

Eitel, B., 2000, Different amounts of pedogenic palygorskite in Southwest African Cenozoic calcretes: Geomorphological, palaeoclimatological and methodological implications: Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie NF Supplement, 121, 139–149. [ Links ]

Eitel, B., Blümel, W.D., 1997, Pans and dunes in the SW Kalahari (Namibia): Geomorphology and evidence for Quaternary paleoclimates: Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie Supplement, 111, 73–95. [ Links ]

Eitel, B., Zöller, L., 1996, Soils and sediments in the basin of Dieprivier–Uitskot (Khorixas District, Namibia): Age, geomorphic and sedimentological investigation; palaeoclimatic interpretation: Paleoecology of Africa, 24, 159–172. [ Links ]

Eitel, B., Blümel, W.D., Hüser, K., 2004, Palaeoenvironmental transitions between 22 ka and 8 ka in monsoonally influenced Namibia, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 167–194. [ Links ]

English, P., Spooner, N.A., Chappel, J., Questiaux, D.G., Hill, N.G., 2001, Lake Lewis basin, central Australia: environmental evolution and OSL chronology: Quaternary International, 83–85, 81–101. [ Links ]

Eugster, H.P., 1969, Inorganic bedded cherts from the Magadi area, Kenya: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 22, 1–31. [ Links ]

Eugster, H.P., Hardie, L.A., 1978, Saline Lakes, in Lerman, A. (ed.), Lakes: Chemistry, Geology, Physics: Berlin, Springer, 237–293. [ Links ]

Fahey, J.J., Mrose, M.E., 1962, Saline minerals from the Green River formation: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper, 405, 50 p. [ Links ]

Fang, J.Q., 1991, Lake evolution during the past 30000 years in China, and its implications for environmental change: Quaternary Research, 36, 27–60. [ Links ]

Faure, H., Elouard, P., 1967, Scheme des variations du niveau de l'ocean Atlantique sur la cote de l'ouest de l'Afrique depuis 40000 ans: Comptes Rendas Academie des Sciences Paris D, 265, 784–787. [ Links ]

Felix–Henningsen, P., 2000, Paleosols on Pleistocene dunes as indicators of Paleo–monsoon events in the Sahara of East Niger: Catena, 41, 43–60. [ Links ]

Felix–Henningsen, P., 2004, Genesis and Paleoecological interpretation of swamp ore deposits at Sahara Paleo–lakes of East Niger, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix—Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 47–72. [ Links ]

Fink, J., Kukla, G.J., 1977, Pleistocene climates in central Europe: at least 17 interglacials after the Olduvai event: Quaternary Research, 7, 363–371. [ Links ]

Fromm, R., Hachicha, T., Smykatz–Kloss, W., 2005, Aridic crusts and vein mineralisations in the playa Areg el Makrzene, South Tunisia: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 65, 357–373. [ Links ]

Gallet, S., Jahn, B.M., Torii, M., 1996, Geochemical characterization of the Luochuan loess–paleosol sequence, China, and paleoclimatic implications: Chemical Geology, 133, 67–88. [ Links ]

Gasse, F., Fontes, J.C.H., Plaziat, J.C., Carbonel, P., Kaczmarka, I., de Dekker, P., Soulie–Märsche, I., Callot, Y., Dupeuple, J.A., 1987, Biological remains, geochemistry and stable isotopes for the reconstruction of environmental and hydrological changes in the Holocene lakes from North Sahara: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 60, 1–46. [ Links ]

Gaylord, D.R., 1990, Holocene palaeoclimatic fluctuations revealed from dune and interdune strata in Wyoming: Journal of Arid Environments, 18, 123–138. [ Links ]

Geyh, M.A., 2005, Handbuch der chemischen und physikalischen Altersbestimmung: Darmstadt, Germany, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 211 p. [ Links ].

Geyh, M.A., Eitel, B., 1998, Radiometric dating of young and old calcrete: Radiocarbon, 40, 795–802. [ Links ]

Geyh, M.A., Jäkel, D., 1974, Spätpleistozäne und holozäne Klimageschichte der Sahara aufgrund zugänglicher 14C–Daten: Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie NF, 18, 82–98. [ Links ]

Glennie, K.W., 1970, Desert Sedimentary Environment: Amsterdam, Elsevier, 222 p. [ Links ]

Glennie, K.W., Singhvi, A.K., 2002, Event stratigraphy, paleoenvironment and chronology of SE Arabian deserts: Quaternary Science Review, 21, 853–869. [ Links ]

Goudie, A.S., Pye, K., 1983, Chemical sediments and geomorphology: Precipitates and residua in the near–surface environment: London, Academic Press, 439 p. [ Links ]

Goudie, A.S., Wells, L.G., 1995, The nature, distribution and formation of pans in arid zones: Earth Science Review, 38, 1–69. [ Links ]

Grunert, J., Lehmkuhl, F., 2004, Aeolian sedimentation in arid and semi–arid environments of Western Mongolia, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 195–218. [ Links ]

Grunert, J., Lehmkuhl, F., Walther, M., 2000, Paleoclimatic evolution of the Uvs Nuur Basin and adjacent areas (Western Mongolia): Quaternary International, 65/66,171–192. [ Links ]

Guo, Z., Petit–Maire, N., Kröpelin, S., 2000, Holocene non–orbital climatic events in present–day arid areas of northern Africa and China: Global and Planetary Change, 26, 97–103. [ Links ]

Harris, S.A., 1986, The Permafrost Environment: London, Croom Helm, 276 p. [ Links ]

Heine, K., 1990, Some observations concerning the age of the dunes in the Western Kalahari and palaeoclimatic implications: Paleoecology of Africa, 21,161–178. [ Links ]

Heine, K., 1998, Climatic change over the past 135000 years in the Namib desert (Namibia) derived from proxy data: Paleoecology of Africa, 25, 171–198. [ Links ]

Heine, K., 2004, Little Ice Age climatic fluctuations in the Namib desert, Namibia, and adjacent areas: Evidence of exceptionally large floods from slack water deposits and desert soil sequences, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 137–165. [ Links ]

Heine, K., Heine, J.T., 2002, A paleologic re–interpretation of the Homeb silts, Kuiseb river, central Namib desert (Namibia) and paleoclimatic implications: Catena, 48, 107–130. [ Links ]

Hoefs, J., 1987, Stable Isotope Geochemistry: Berlin, Springer, 241 p. [ Links ]

Hofmann, J., 1993, Geomorphologische Untersuchungen zur jungquartären Klimageschichte des Helan Shan und seines westlichen Vorlandes (Autonomes Gebiet Innere Mongolei/VR China): Berliner Geographische Abhandlungen, 57, 187. [ Links ]

Hofmann, J., Geyh, M.A., 1998, Untersuchungen zum 14C–Reservoireffekt an rezenten und fossilen lakustrinen Sedimenten aus dem Südosten der Badain Jaran–Wüste (Innere Mongolei/VR China): Berliner Geographische Abhandlungen, 63, 83–98. [ Links ]

Holland, G.J., McBride, J.L., Nicholls, N., 1988, Australian region tropical cyclones and the greenhouse effect, in Pearman, G.I. (ed.), Greenhouse: Planning for Climatic Change: Melbourne, CSIRO, 438–455. [ Links ]

Holser, W.T., 1979, Mineralogy of Evaporites, in Burns, R.G. (ed.), Marine Minerals: Mineralogical Society of America Short Course Notes vol. 6: Washington, D.C., Mineralogical Society of America, 124–150. [ Links ]

Jain, M., Tandon, S.K., 2003, Fluvial response to Late Quaternary climate changes, western India: Quaternary Science Reviews, 22, 2223–2235. [ Links ]

Jäkel, D., 1995, Die Wüsten Chinas. Aufschlussreiche Zeugen globaler Klimaschwankungen: Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau, 10, 365–373. [ Links ]

Jäkel, D., 2004, Critical comments on the interpretation and publication of 14C, TL, OSL and 230Th/U dates and on the problem of teleconnections between global climatic processes, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 233–242. [ Links ]

Joachim, H., 1988, Mineralogische Untersuchungen an Sil– und Ferricretes aus dem Kapland (Südafrika): Karlsruhe, Germany, University of Karlsuhe, Ph.D. Thesis. [ Links ]

Juyal, N., Kar, A., Rayaguru, S.N., Singhvi, A.K., 2003, Luminescence chronology of aeolian deposition during the late Quaternary on the southern margin of the Thar Desert, India: Quaternary International, 104, 87–98. [ Links ]

Kar, A., 1990, The megabarchanoids of the Thar: Their environment, morphology and relationship with longitudinal dunes: The Geographical Journal, 156, 51–61. [ Links ]

Knabe, K., 2000, Sedimentpetrographische und geochemische Untersuchungen an Sedimenten im Wadi Feiran (Südsinai) zur Klärung ihrer Herkunft und Ablagerungsbedingungen.–Paläoklimatische Überlegungen: Karlsruhe, Germany, University of Karlsruhe, Ph.D. Thesis. [ Links ]

Koessl, H., 1988, Mineralogische und hydrogeochemische Untersuchungen im Gipskarstgebiet von Foum Tatahouine (SE–Tunesien) und im SW–deutschen Gipskeuper (Obersontheim, Raum Schwäbisch Hall): Karlsruhe, Germany, University of Karlsruhe, Ph.D. Thesis. [ Links ]

Kröpelin, S., 1993, Zur Rekonstruktion der spätquartären Umwelt am unteren Wadi Howar (südöstliche Sahara/NW Sudan): Berliner Geographische Abhandlungen, 54, 1–293. [ Links ]

Kukla, G., 1987, Loess stratigraphy in China: Quaternary Science Review, 6, 191–219. [ Links ]

Lancaster, N., 1981, Paleoenvironmental implications of fixed dune systems in Southern Africa: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 33, 327–346. [ Links ]

Lancaster, N., 1989, The Namib Sand Sea: Dune Forms, Processes and Sediments: Rotterdam, Balkema, 192 p. [ Links ]

Lancaster, N., 1995, Geomorphology of Desert Dunes: London, Rutledge, 290 p. [ Links ]

Lehmkuhl, F., 1995, Geomorphologische Untersuchungen zum Klima des Holozäns und Jungpleistozäns Osttibets: Göttinger Geographische Abhandlungen, 102, 1–184. [ Links ]

Leng, M.J., Marshall, J.D., 2004, Palaeoclimate interpretation of stable isotope data from lake sediment archives: Quaternary Science Reviews, 23, 811–831. [ Links ]

Leng, M.J., Lamb, A.L., Marshall, J.D., Wolfe, B.B., Jones, M.D., Holmes, J.A., Arrowsmith, C., 2005, Isotope in lake sediments, in Leng, M.J. (ed.), Isotopes in Paleoenvironmental Research, vol.10: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Springer, 148–184. [ Links ]

Liu, C., Fu, G., 1996, The impact of climatic warming on hydrological regimes in China: an overview, in Jones, J.A.A., Liu, C., Woo, M.K., Kung, H.T. (eds.), Regional Hydrological Response To Climate Change: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Kluwer, 133–151. [ Links ]

Lowe, J.J., Walker, M.J.C., 1984, Reconstructing Quaternary Environments: London, Longman, 389 p. [ Links ]

Maley, J., 1983, Histoire de la vegetation et du climat de l'Afrique nord–tropicale au Quaternaire recent: Bothalia, 14, 377–389. [ Links ]

Mason, B., Moore, C.B., 1982, Principles of Geochemistry: New York, Wiley, 344 p. [ Links ]

Mehrshabi, D., Thomas, D.S.G., O Hara, S., 2003, Late Quaternary Palaeoenvironmental changes, Ardakan Kavir (Playa), Central Iran, in Alsharhan, A.S., Wood, W.W., Goudie, A.S., Fowler, A., Abdellatif, E.M. (eds.), Desertification in the Third Millenium: Lisse, The Netherlands, Swet & Zweitlinger Pubishers, 99–110. [ Links ]

Metcalfe, S., Say, A., Black, S., McCulloch, R., O'Hara, S., 2002, Wet conditions during the Last Glaciation in the Chihuahuan Desert, Alta Babicora Basin, Mexico: Quaternary Research, 57, 91–101. [ Links ]

Meyers, P.A., Teranes, J.L., 2001, Sediment organic matter, in Last, W.M., Smol, J.P. (eds.), Tracking environmental change using lake sediments, vol. 2: Physical and Geochemical Techniques: Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 239–269. [ Links ]

Mezquita, F., Tapia, G., Roca, J.R., 1999, Ostracoda from springs on the eastern Iberian Peninsula: Ecology, biogeography and palaeolimnological implications: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 148, 65–85. [ Links ]

Millot, G., 1964, Geologie des Argiles: Paris, Masson, 499 p. [ Links ]

Mischke, S., Hofmann, J., Schudack, M.E., 2004, Ostracod ecology of alluvial loess deposits in an eastern Tian Shan palaeo–lake (NW China), in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 219–231. [ Links ]

Monger, H.C., Daugherty, L.A., 1991, Neoformation of Palygorskite in a Southern New Mexico Aridisol: Soil Science Society of America Journal, 55, 1646–1650. [ Links ]

Nahon, D., 1976, Cuirasses ferrugineuses et encroutements calcaires au Senegal occidental et en Mauritanie. Systems evolutifs: geochimie, structures, relais et coexistence: Marseille, Université d'Aix–Marseille III, Ph.D. Thesis [ Links ]

Nanson, G., Tooth, S., 1999, Arid–zone rivers as indicators of climatic change, in Singhvi, A.K., Derbyshire, E. (eds.), Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction in Arid Lands: New Delhi, Oxford Press, 75–216. [ Links ]

Nesbitt, H.W., Young, G.M., 1982, Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites: Nature, 299, 715–717. [ Links ]

Nir, D., 1974, Lacustrine/fluviatile sediments in Feiran and Tarfat el Kudrein: Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie Supplementband, 22, 32–34. [ Links ]

Ordóñez, S., Sánchez Moral, S., De los Angeles, M., Del Cura, G., Rodríguez Badiola, E., 1994, Precipitation of salts from Mg2+– (Na+)–SO42– Cl–playa lake brines: the endorheic saline ponds of La Mancha, central Spain, in Renaut, R.W., Last, W.M. (eds.), Sedimentology and Geochemistry of Modern and Ancient Saline Lakes: Society for Sedimentary Geology Special Publication, 50, 61—71. [ Links ]

Palacios–Fest, M., Carreño, A.L., Ortega–Ramirez, J.R., Alvarado–Valdez, G., 2002, A paleoenvironmental reconstruction of Laguna Babicora, Chihuahua, Mexico based on ostracode paleoecology and trace element shell chemistry: Journal of Paleolimnology, 27, 185–206. [ Links ]

Pandarinath, K., Prasad, S., Gupta, S.K., 1999, A 75 ka record of Palaeoclimatic changes inferred from crystallinity of illite from Nal Sarovar, western India: Journal of the Geological Society of India, 54, 515–522. [ Links ]

Perthuisot, J.P., 1976, Une sebkha sulfatee sodique en pays sedimentaire. La sebkha Oum el Krialate (Tunisie): Géologie Méditerranéenne, 3, 265–274. [ Links ]

Petit–Maire, N., 1986, Paleoclimate in the Sahara of Mali: a multidisciplinary study: Episodes, 9/1, 7–16 [ Links ]

Petit–Maire, N., 1987, Interglacial environments in presently hyperarid Sahara: Paleoclimatic implications, in Leinen, M., Sarnthein, M. (eds.), Paleoclimatology and Paleometeorology: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Kluwer, 637–661. [ Links ]

Petit–Maire, N., 1991, Le Sahara: des paleoclimats aux climats du futur, in Caruba, R., Dars, R. (eds.), Geologie de la Mauritanie: Paris, Editions du CNRS, 141–150. [ Links ]

Prasad, S., Kusumgar, S., Gupta, S.K., 1997, A mid to late Holocene record of palaeoclimatic changes from Nal Sarovar: A palaeodesert margin lake in western India: Journal of Quaternary Science, 12, 153–159. [ Links ]

Prell, W.L., Kutzbach, J.E., 1987, Monsoon variability over the past 150000 years: Journal of Geophysical Research, 92, 8411–8425. [ Links ]

Pye, K., Tsoar, H., 1990, Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes: London, Unwin Hyman, 396 p. [ Links ]

Qin, B., Yu, G., 1998, Implications of lake level variations at 6 ka and 18 ka in mainland Asia: Global and Planetary Change 18, 59–72. [ Links ]

Reheis, M.C., 1990, Influence of climate and eolian dust on the major element chemistry and clay minerals of soils in the Northern Bighorn basin, USA: Catena, 17, 219–248. [ Links ]

Roberts, S.M., Spencer, R.J., 1995, Paleotemperatures preserved in fluid inclusions in halite: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 59, 3929–3942. [ Links ]

Rögner, K., Smykatz–Kloss, W., 1991, The deposition of eolian sediments in lacustrine and fluvial environments of Central Sinai (Egypt): Catena Supplement, 20, 75–91. [ Links ]

Rögner, K., Smykatz–Kloss, W., Zöller, L., 1999, Oberpleistozäne paläoklimatische Veränderungen im Zentral–Sinai (Ägypten): Erdkunde, 53, 220–230. [ Links ]

Rögner, K., Knabe, K., Roscher, B., Smykatz–Kloss, W., Zöller, L., 2004, Alluvial loess in the Central Sinai: Occurrence, origin, and palaeoclimatological consideration, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 79–99. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D, Smykatz–Kloss, W., 2007, REE geochemistry of the recent playa sediments from the Thar Desert, India: An implication to playa sediment provenance: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 67, 55–68. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D., Sinha, R., Smykatz–Kloss, W., 2001, Mineralogy and geochemistry of the evaporitic crust from the hypersaline Sambhar Lake playa, Thar Desert, India: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 61, 241–253. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D., Smykatz–Kloss, W., Sinha, R., 2006, Late Holocene geochemical history inferred from Sambhar and Didwana playa sediments, Thar Desert, India: Comparison and synthesis: Quaternary International, 144, 84–98. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D., Caballero, M., Lozano, R., Smykatz–Kloss, W., 2008a, Geochemistry of late quaternary sediments from Tecocomulco Lake, central Mexico: Implication to chemical weathering and provenance: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 68, 383–393. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D., Smykatz–Kloss, W., Morton, O., 2008b, Geochemical zones and reconstruction of late Holocene environments from shallow core sediments of the Pachapadra paleo–lake, Thar Desert, India: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 68, 313–322. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D., Nagar, Y.C., Juyal, N., Smykatz–Kloss, W., Singhvi, A.K., 2009, Geochemical signatures of Late Holocene paleo–hydrological changes from Phulera and Pokharan saline playas near the eastern and western margins of the Thar Desert, India: Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 34, 275–286. [ Links ]

Roy, P.D., Caballero, M., Lozano, R., Ortega, B., Lozano, S., Pi, T., Israde, I., Morton, O., 2010, Geochemical record of late Quaternary paleoclimate from lacustrine sediments of paleo–lake San Felipe, western Sonora desert, Mexico: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 29, 586–596. [ Links ]

Rust, U., 1989, Grundsätzliches über Flussterrassen als paläoklimatische Zeugen in der südwestafrikanischen Namibwüste: Paleoecology of Africa, 20, 119–132. [ Links ]

Sarnthein, M., 1978, Sand deserts during glacial maximum and climatic optimum: Nature, 272, 43–46. [ Links ]

Schulz, E., 1987, Die holozäne Vegetation der zentralen Sahara (N Mali, N Niger, SW Libya): Paleoecology of Africa, 18, 143–161 [ Links ]

Schumm, A., 1977, The Fluvial System: London, Wiley, 338 p. [ Links ]

Schütt, B., 1998, Reconstruction of Holocene Paleoenvironments in the endorheic Basin of Laguna de Gallocanta, Central Spain, by investigation of mineralogical and geochemical characters from lacustrine sediments: Journal of Paleolimnology, 20, 217–234. [ Links ]

Schütt, B., 2004, The chemistry of playa–lake sediments as a tool for the reconstruction of Holocene environmental conditions – a case study from the central Ebro basin, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 5–30. [ Links ]

Sharp, Z., 2007, Principles of stable isotope geochemistry, New Jersey, Pearson Prentice Hall, 344 p. [ Links ]

Singer, A., 1979, Palygorskite in Sediments: Detrital, diagenetic or neoformed — A critical review: Geologische Rundschau, 68, 996–1008. [ Links ]

Singer, A., 1984, Pedogenic palygorskite in the arid environment, in Singer, A., Galan, E. (eds.), Palygorskite, Sepiolite–Occurrence, genesis and uses: Developments in Sedimentology 37, 169–177. [ Links ]

Singhvi, A.K., Kar, A., 2004, The aeolian sedimentation record of the Thar Desert, in Singhvi, A.K., (ed.), Quaternary History and Palaeoenvironmental Record of the Thar Desert in India: Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, 113, 371–401. [ Links ]

Sinha, R., Raymahashay, B.C., 2004, Evaporite mineralogy and geochemical evolution of the Sambhar Salt Lake, Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India: Sedimentary Geology, 166, 59–71. [ Links ]

Sinha, R., Smykatz–Kloss, W., Stüben, D., Harrison, S.P., Berner, Z., Kramar, U., 2006, Late Quaternary palaeoclimatic reconstruction from the lacustrine sediments of the Sambhar playa core, Thar Desert margin, India: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 233, 252–270. [ Links ]

Sirocko, F., 1995, Abrupt change in monsoonal climate: evidence from the geochemical composition of Arabian Sea sediments: Kiel, University of Kiel, Habilitation thesis. [ Links ]

Sirocko, F., Sarnthein, M., 1989, Wind–borne deposits in the northwestern Indian Ocean: Records of Holocene sediments versus modern satellite data, in Leinen, M., Sarnthein, M. (eds.), Paleoclimatology and Paleometeorology: Modern and Past Patterns of Global Atmospheric Transport: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Kluwer, 401–433. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Goebelbecker, J., 1992, Dedolomitization and salt formation in a semi–arid environment, in Matthess, G., Hirsch, P., Frimmel, F., Schulz, H.D., Usdowski, H.E. (eds.), Progress in Hydrogeochemistry: Berlin, Springer–Verlag, 184–189. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Istrate, G., Hötzl, H., Koessl, H., Wohnlich, S., 1985, Occurrence and formation of bassanite, CaSO441/2H2O, in the gypsum karst area of Foum Tatahouine, South Tunisia: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 44, 67–77. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Hötzl, H., Koessl, H., 1992, Mineralogy and hydrogeochemistry of the gypsum karst of Foum Tatahouine, South Tunisia, in Matthess, G., Hirsch, P., Frimmel, F., Schulz, H.D., Usdowski, H.E. (eds.), Progress in Hydrogeochemistry: Berlin, Springer–Verlag, 175–184. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Knabe, K., Zöller, L., Rögner, K., Hüttl, C., 1998, Paleoclimatic changes in Central Sinai, Egypt: Paleoecology of Africa, 25, 143–155. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Roscher, B., Knabe, K., Rögner, K., Zöller, L., 1999/2000, Wüstenforschung und Paläoklimatologie im zentralen Sinai: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 59, 245–258. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Roscher, B., Rögner, K., 2003, Pleistocene Lakes in Sinai, Egypt, in Alsharhan, A.S., Wood, W.W., Goudie, A.S., Fowler, A., Abdellatif, E.M. (eds.), Desertification in the Third Millenium: Lisse, The Netherlands, Swet & Zweitlinger Pubishers, 111–116. [ Links ]

Smykatz–Kloss, W., Smykatz–Kloss, B., Naguib, N., Zöller, L., 2004, The reconstruction of palaeoclimatological changes from mineralogical and geochemical compositions of loess and alluvial loess profiles, in Smykatz–Kloss, W., Felix–Henningsen, P. (eds.), Palaeoecology of Quaternary Drylands, Lecture Notes on Earth Sciences: Berlin, Springer, 101–118. [ Links ]

Spencer, R.J., Yang, W., Roberts, S.M., Krouse, H.R., 2003, Hydrology and climate change (200 to 100 ka), Death Valley, California, USA, in Alsharhan, A.S., Wood, W.W., Goudie, A.S., Fowler, A., Abdellatif, E.M. (eds.), Desertification in the Third Millenium: Lisse, The Netherlands, Swet & Zweitlinger Pubishers, 117–122. [ Links ]

Sponholz, B., Baumhauer, R., Felix–Henningsen, P., 1993, Fulgurites in the South Central Sahara, Republic of Niger, and their palaeoenvironmental significance: The Holocene, 3, 97–104. [ Links ]

Stengele, F., Smykatz–Kloss, W., 1995, Mineralogical and geochemical study of Holocene sebkha sediments in southeastern Tunisia: Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry, 55, 241–256. [ Links ]

Summerfield, M.A., 1983, Silcrete as a palaeoclimatic indicator: evidence from the southern Africa: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 41, 65–79. [ Links ]

Summerfield, M.A., 1991, Global Geomorphology: London, Longman, 560 p. [ Links ]

Thomas, D.S.G., 1989, Arid Zone Geomorphology: London, Bellaven, 250 p. [ Links ]

Thomas, D.S.G, Shaw, P.A., 1991, The Kalahari Environment: London, Cambridge University Press, 298 p. [ Links ]

Tooley, M.J., Shennan, I., 1987, Sea–Level Changes (Institute of British Geographers Special Publications 20): Oxford, Blackwell, 416 p. [ Links ]

Tricart, J., Cailleux, A., 1972, Introduction to Climatic Geomorphology: London, Longman, 295 p. [ Links ]

Tyson, P.D., 1986, Climatic Change and Variability in Southern Africa: Capetown, South Africa, Oxford University Press, 220 p. [ Links ]

Usdowski, E., Dietzel, M., 1998, Atlas and Data of Solid Solution Equilibria of Marine Evaporites: Berlin, Springer, 316 p. [ Links ]

Vogel, J.C., 1989, Evidence of past climatic change in the Namib Desert: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 70, 355–366. [ Links ]

von Grafenstein, U., Erlenkeuser, H., Müller, J., Jonzel, J.P., Johnson, S., 1998, The cold event 8200 years ago, documented in oxygen isotope research of precipitation in Europe and Greenland: Climate Dynamics, 14, 73–81. [ Links ]

Washburn, A.L., 1979, Geocryology: A Survey of Periglacial Processes and Environments: London, Edward Arnold, 406 p. [ Links ]

Wasson, R.J., Rajaguru, S.N., Misra, V.N., Agrawal, D.P., Dhir, R.P., Singhvi, A.K., Rao, K.K., 1983, Geomorphology, late Quaternary stratigraphy and palaeoclimatology of the Thar dunefield: Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie Supplementband, 45, 117–151 [ Links ]

Wasson, R.J., Smith, G.I., Agrawal, D.P., 1984, Late Quaternary sediments, minerals, and inferred geochemical history of Didwana Lake, Thar Desert, India: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 46, 349–372. [ Links ]

Wenigwieser, S., 1992, Mineralogische Untersuchungen an den Evaporiten und Tonen des Wadi El–Natrun (NW–Ägypten): Karlsruhe, Germany, University of Karlsuhe, Ph.D Thesis. [ Links ]

Wiedemann, H.G., Smykatz–Kloss, W., 1981, Thermal studies on thenardite: Thermochimica Acta, 50, 17–29. [ Links ]

Williams, M.A.J., Balling, R.C., 1996, Interactions of Desertification and Climate: London, Edward Arnold, 270 p. [ Links ]

Wünnemann, B., Pachur, H.J., Li, J., Zhang, H., 1998, Chronologie der pleistozänen und holozänen Seespiegelschwankungen des Gaxun Nur/Sogo Nur und Baijian Hu, Innere Mongolei, NW China: Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen,142, 191–206. [ Links ]

Yaalon, D.H., Wieder, M., 1976, Pedogenic palygorskite in some arid brown (calciorthid) soils of Israel: Clay Minerals, 11, 73–80. [ Links ]

Yadav, D.N., 1997, Oxygen isotope study of evaporating brines in Sambhar Lake, Rajasthan, India: Chemical Geology, 138, 109–118. [ Links ]

Young, R.W., 1985, Silcrete distribution in Eastern Australia: Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie, 29, 21–36. [ Links ]

Zöller, L., 1995, Würm– und Rißlößstratigraphie und Thermolumineszenz –Datierung in Süddeutschland und angrenzenden Gebieten: Heidelberg, Germany, Universität Heidelberg, Habilitation thesis. [ Links ]