Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agrociencia

versión On-line ISSN 2521-9766versión impresa ISSN 1405-3195

Agrociencia vol.52 no.5 Texcoco jul./ago. 2018

Crop science

Biological efficacy of the inhibitor herbicides of acetyl coenzyme a carboxylase and acetolactate synthase and the presence of resistance in Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Beauv.

1 Botánica. Campus Montecillo. Colegio de Posgraduados, 56230. Montecillo, Estado de México. jovanybolanos@gmail.com; euscanga@colpos.mx; jkohashi@colpos.mx.

2 Parasitología Agrícola. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. 56230. Chapingo, Estado de México. atafoyarazo@yahoo.com.mx

3 Departamento de Ingeniería Genética, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Avanzados del IPN. Unidad Irapuato. Libramiento Norte Carretera Irapuato-León, Km. 9.6, Irapuato, Guanajuato. CP 36821. ruben.torres@cinvestav.mx

In the state of Guanajuato, Mexico, Echinochloa crus-galli is the main weed in wheat and is controlled with inhibitors herbicides of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (ACCase) and acetolactate synthetase (ALS), but its control is poor. The objective of this research was to determine the biological efficacy of the herbicides used in wheat and the presence of resistance in E. crus-galli. The experiment was carried out in two phases: 1) biological efficacy and, 2) presence of resistance. To evaluate the biological efficacy in six biotypes (one bioassay per biotype) we applied clodinafop propargil and pinoxaden, ACCase inhibitor herbicides, and sodium flucarbazone and mesosulfuron methyl + iodosulfuron methyl, ALS inhibitor herbicides, in doses of 60, 55, 28 and 15 g of a.i. ha-1, respectively. Each herbicide was one treatment plus a control, and the design was completely randomized with four replications. Regarding the presence of resistance we evaluated the effect of increasing doses of sodium flucarbozone and mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl on the production of dry biomass of the six biotypes, and calculated the resistance index. A completely randomized blocks design was used with four replications. Biological efficacy: the application of the ACCase inhibitor herbicides in the biotypes showed a control of 99 %, and the weight of dry biomass was lower, while the application of the ALS inhibitors caused a control of 42 %, except in one biotype, which was 77 % and it was considered as susceptible. The dry weight of the biomass in some cases was similar to that of the control. Presence of resistance: the resistance index to mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl was greater than 2.0 in two biotypes, while for sodium flucarbazone the resistance indices were lower than 1.35. Therefore, the E. crus-galli resistance to mesosulfuron methyl + iodosulfuron methyl was confirmed.

Key words: Echinochloa crus-galli; chemical control; efficacy; resistance; response dose

En Guanajuato, Echinochloa crus-galli es la principal maleza en el trigo y se controla con herbicidas inhibidores de la acetil coenzima A carboxilasa (ACCasa) y la acetolactato sintetasa (ALS), pero se ha observado un control deficiente. El objetivo de esta investigación fue determinar la efectividad biológica de los herbicidas usados en el trigo y la presencia de resistencia en E. crus-galli. El experimento se realizó en dos fases: 1) efectividad biológica y, 2) presencia de resistencia. Para evaluar efectividad biológica, en seis biotipos (un bioensayo por biotipo) se aplicaron clodinafop propargil y pinoxaden, inhibidores de la ACCasa, y flucarbazone sódico y mesosulfuron metil+iodosulfuron metil, inhibidores de la ALS, en dosis de 60, 55, 28 y 15 g de a.i. ha-1, respectivamente. Cada herbicida fue un tratamiento más un testigo, y el diseño fue completamente al azar con cuatro repeticiones. Para presencia de resistencia se evaluó el efecto de dosis crecientes de flucarbozone sódico y mesosulfuron metil+iodosulfuron metil en la producción de biomasa seca de los seis biotipos y se calculó el índice de resistencia, y el diseño fue bloques completos al zar con cuatro repeticiones. Efectividad biológica: la aplicación de los inhibidores de la ACCasa en los biotipos mostró un control de 99 % y el peso de biomasa seca fue menor, mientras que la aplicación de los inhibidores de la ALS causó un control de 42 %, excepto en un biotipo que fue 77 % y se consideró como susceptible, y el peso seco de la biomasa en algunos casos fue similar a la del testigo. Presencia de resistencia: el índice de resistencia a mesosulfuron metil+iodosulfuron metil fue mayor a 2.0 en dos biotipos, mientras que para el flucarbazone sódico los índices de resistencia fueron menores de 1.35. Por lo tanto, se confirmó la resistencia de E. crus-galli a mesosulfuron metil+iodosulfuron metil.

Palabras claves: Echinochloa crus-galli; control-químico; efectividad; resistencia; dosis-respuesta

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivun L.) is one of the three highest production cereals in the world along with corn and rice, and it is used to produce food products and balanced diets in livestock. In 2016, in Mexico, the harvested area of wheat grain was 612, 866 ha with a production of 3, 606, 144 t. The states with the largest area sown that year were Sonora, Baja California, Sinaloa, Guanajuato and Michoacán (SIAP, 2016).

Wheat production is affected by the interference of weeds, which are one of the main limitations that reduce yields per surface unit (Ross and Lembi, 2009). Cruz et al. (2004) showed that when weeds competed with wheat throughout the cycle, yield decreased by 90 %. Within the crop there is a great variety of weeds that differ according to the region of the country, but there are some very aggressive in most of the producing areas of this cereal.

In the state of Guanajuato, the most important weeds in the wheat crop are: of narrow leaf, Avena fatua L., Phalaris minor Retz., P. paradoxa L. and Echinochloa spp; and of broad leaf, Bidens spp., Rhaphanus raphanistrum L., Brassica campestris L., Helianthus annuus L., Brassica nigra (L.) W.G.J. Koch, Chenopodium album L. Bosc ex Moq., Sonchus oleraceus L., and Malva parviflora L. Echinochloa crus-galli occurs mainly in the rainy season and can cause total losses in yield if no efficient control is carried out.

Due to the type of wheat planting, it is difficult to apply an alternative control method to the use of herbicides (Tafoya et al., 2009; Tafoya and Carrillo, 2009). Chemical control is practical, efficient and relatively inexpensive, but its repeated use leads to a selection of resistant weed populations (Powles and Yu, 2010). The development of resistant populations occurs through the selection pressure imposed by the frequent use of one or more herbicides with the same action mode (Christoffers, 1999, Fischer, 2013), the biological characteristics of the weed, the specificity of the herbicide, the diversity of the resistance genes involved and herbicide efficacy (Valverde et al., 2000; Cerdeira and Duke, 2006).

Heap (2016) points out that in the world there are 47 weed species resistant to inhibitor herbicides of the enzyme acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (ACCase) and 159 resistant to herbicides inhibitors of the enzyme acetolactate synthase (ALS), in both cases species of the genus Echinochloa are included. Of these, 19 biotypes have developed resistance to herbicides that inhibit ALS and 17 to herbicides that inhibit ACCase. Echinochloa crus-galli is considered the sixth weed most resistant to herbicides after Lolium rigidum Gaud., Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson, Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist, Avena fatua L. and A. tuberculatus (Moq.) J.D. Sauer (Heap, 2014).

Mallory-Smith et al. (1990) and Devine (1997) mention that some herbicides, such as ACCase inhibitors, can select resistant biotypes in one to five generations. This limited number of generations is due to the high specificity of action site, the high frequency of mutations in the nuclear gene that encodes the enzyme and the possibility that different semi-dominant mutations alter the site of coupling of the herbicide in the enzyme (Gressel, 2002, Tranel and Wright, 2002, Délye, 2005). The rapid increase in resistance to ALS inhibitor herbicides is attributed in part to the high frequency of natural mutation in the center of action of the enzyme (Devine and Preston, 2000).

In the state of Guanajuato the control of E. crus-galli has been deficient (visual appreciation of the first author), which is attributed to the resistance development of this species to the herbicides of traditional use in the region, however there is no scientific evidence. Knowledge of the presence of resistance is necessary to determine the actions in the weed control, which range from the use of herbicides with different modes of action, to alternative control methods (mechanical, manual, biological and legal). Therefore, the objective of the present research was to determine the biological efficacy of the herbicides commonly used in wheat crop and the resistance presence to these herbicides in E. crus-galli collected in the state of Guanajuato. The hypothesis was that there are biotypes of E. crus-galli that have developed resistance to the herbicides used in Guanajuato for the control of narrow leaf weeds in cereals.

Materials and Methods

During the spring of 2015, in the state of Guanajuato, we collected samples of five biotypes of E. crus-galli in commercial wheat plots in which herbicides were applied, and this species was not controlled (Table 1). The biotype considered susceptible was collected in an area surrounding the initial section of an irrigation water distribution channel, where we were certain that no herbicides were used before. Then, we separated the seeds (approximately 200 g per collection site) from the rest of the infrutescence by using stainless steel sieves and stored them in paper bags under laboratory conditions until they were used.

Table 1 Geographical location of sites and date of collection of Echinochloa crus-galli biotypes in the state of Guanajuato.

| Biotipo | Fecha de recolección | Latitud N | Longitud O | Altitud (m) | Localidad |

| I | 12/04/15 | 20° 33' 05'' | 101° 26' 53'' | 1715 | Munguía, Irapuato |

| II | 01/05/15 | 20° 23' 10" | 101° 39' 53" | 1697 | La Granjera, Pénjamo |

| III | 01/05/15 | 20° 21' 37" | 101° 34' 50" | 1704 | La Lobera, Huanímaro |

| IV | 02/05/15 | 20° 39' 37" | 101° 08' 19" | 1737 | La Ordeña, Salamanca |

| V | 02/05/15 | 20° 25' 32" | 101° 24' 05" | 1704 | Piedras Negras, Abasolo |

| Sus.† | 19/05/15 | 20° 29' 59'' | 101° 28' 55'' | 1700 | Los Juanes, San Felipe |

† Susceptible biotype

We placed the seeds in a germination chamber (APT.line® KBWF E5.2, Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany), and exposed them at 38 °C for 24 h. After removing them from the chamber, we placed them in 10 cm diameter Petri dishes on filter paper (Whatman No. 1), and in each Petri dish we applied 20 mL of 0.3 % p/v KNO3 solution.

We put the boxes again in the germination chamber at 30 °C for 24 h, under constant light and 80 % relative humidity; then we washed the seeds with distilled water to remove the remains of the KNO3 solution and kept them in the germination chamber, under the same conditions for 6 d. When the seeds germinated and the seedlings reached 2 cm in height, we transplanted them in plastic pots with a capacity of 500 mL filled with a mixture of field soil and peat moss substrate (Promix flex®) in a ratio of 7:3.

Biological efficacy

At the greenhouse of the weeds and pesticides area of the Department of Agricultural Parasitology of the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, we conducted six bioassays, in which we evaluated the biological efficacy of four herbicides (Table 2) commonly used in Guanajuato in each of the biotypes (population per collection site). In each bioassay, the experimental design was completely randomized with five treatments (application of four herbicides), including the untreated control with four repetitions per treatment. The experimental unit was a pot with three plants of E. crus-galli.

Table 2 Common name, dose of application and action mode of the herbicides used in the biological efficacy phase.

| Nombre común | Dosis (g i.a. ha-1) | Modo de acción, inhibidores de: |

| Flucarbazone sódico | 28.0 | ALS |

| Mesosulfuron metil + iodosulfuron metil | 15.0 | ALS |

| Clodinafop propargil | 60.0 | ACCasa |

| Pinoxaden | 55.0 | ACCasa |

| Testigo absoluto | --- | ----- |

i.a. = active ingredient.

The herbicides were applied when the plants presented three to five ligulated leaves. A pressurized spray equipment based CO2 (TS Model) was used, equipped with a flat fan tip from the TeeJet 8002VS series. Prior to the application, we calibrated the spray equipment to determine the volume of water, which was 200 L ha-1.

The variables were the damage percentage at 10, 20 and 30 d after application (DAA), through visual evaluation with the EWRS (European Weed Research Society) scale (Burrill et al., 1976) and dry biomass production of the plants at 30 DAA. To determine the dry biomass, we cut the above-ground part of the three plants of each pot at ground level, then placed them in a drying oven ("Robert Shaw") at 70 °C for 72 h and weighed them with a digital scale (Ohaus, model TAJ602).

With the data we performed an ANOVA with SAS®, version 9.0. Means comparison was carried out with the Tukey test (p≤05). Prior to the analysis, we transformed the percentages to the arcsine function of the square root to comply with the normality and homogeneity of variance.

Presence of resistance

We used the herbicides with deficient control in the previous phase to determine the resistance presence. We conducted two bioassays to evaluate the effect of increasing doses of sodium flucarbozone and mesosulfuron methyl + iodosulfuron methyl (one per herbicide) on the production of dry biomass of the six biotypes of E. crus-galli at 30 DAA.

The experimental design was randomized complete blocks with four replications. The plant material, application equipment and conditions were similar to those used in bioassays of biological efficacy. The treatments evaluated are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Common name and application dose of the herbicides used in the determination of resistance.

| Tratamiento | Flucarbazone sódico (g de i.a. ha-1) | Mesosulfuron metil+iodosulfuron metil (g de i.a. ha-1) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 7 | 3.12 + 0.62 |

| 3 | 14 | 6.25 + 1.25 |

| 4 | 28 | 12.5 + 2.5 |

| 5 | 56 | 25 + 5 |

| 6 | 112 | 50 + 10 |

| 7 | 224 | 100 + 20 |

| 8 | 448 | 200 + 40 |

i.a. = active ingredient.

With the dry biomass values we calculated the ED50 (value that represents the dose of herbicide that inhibits 50 % of the growth of the plants treated in relation to the control plants). For the calculation of this parameter, we used the non-linear model of the dose-response relationship (Valverde et al., 2000).

We estimated the resistance index (IR) as the quotient of the ED50 obtained for the presumed resistant population and the ED50 of the population known as susceptible. In our study, we considered populations as resistant when the IR values were equal to or greater than 2.0 (Valverde et al., 2000).

Results and Discussion

Biological efficacy

In the biological efficacy phase of the four herbicides, we observed significant statistical differences due to the effect of the herbicides in the control of E. crus-galli biotypes at 30 DDA. ACCase-inhibiting herbicides (clodinafop propargyl and pinoxaden) showed good control of all the E. crus-galli biotypes examined in this evaluation and in the two previous ones (data not shown). The control was on average 99 %, with the exception of biotype III, where the control was 95 % (Table 4 and Figure 1). These results were decisive to rule out the suspicion of resistance to these herbicides.

Table 4 Control percentages (30 DDA) of the E. crus-galli biotypes of the state of Guanajuato for the evaluated herbicides.

| Tratamiento | Biotipo | |||||

| Sus | I | II | III | IV | V | |

| Flucarbazone sódico | 75.00 b | 60.00 c | 42.75 b | 25.50 b | 34.12 b | 55.12 b † |

| Clodinafop propargil | 99.50 a | 99.50 a | 99.50 a | 94.43 a | 95.50 a | 99.50 a |

| Pinoxaden | 99.50 a | 99.50 a | 99.50 a | 95.83 a | 99.50 a | 99.50 a |

| Meso.+ Iodos¶ | 79.37 b | 79.37 b | 42.75 b | 25.50 b | 34.12 b | 25.50 c |

| Testigo absoluto | 0.50 c | 0.50 d | 0.50 c | 0.50 c | 0.50 c | 0.50 d |

† Means with different letter in a column are statistically different (Tukey; p ( 0.05).

¶ Mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl

Figure 1 Effect at 30 d after of the application of ACCase inhibitor herbicides (clodinafop propargil and pinoxaden) on the biotypes of E. crus-galli, collected in Guanajuato.

The ALS inhibitor herbicides (sodium flucarbazone and mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl) provided an average control of 77 % in the susceptible biotype (Table 4).

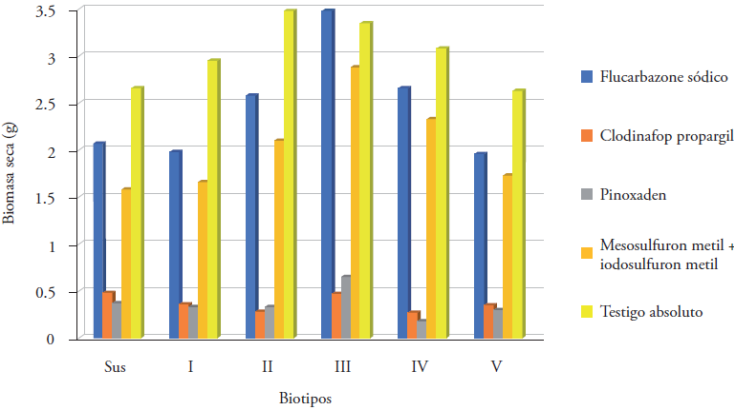

This percentage of control is considered regular, according to the European scale in use. However, with the exception of biotype I, in the other biotypes its effectiveness was low (Figure 2), so we could confirm the suspicion of resistance of these biotypes to the aforementioned herbicides.

Figure 2 Effect at 30 d after of the application of the herbicides inhibitors of ALS (Meso. + Iod. = Mesosulfuronmetil+iodosulfuron-methyl and sodium flucarbazone) in the biotypes of E. crus-galli, collected in Guanajuato.

The determinations of dry biomass confirmed the results obtained from the final visual evaluation. The biotypes treated with pinoxaden and clodinafop propargil had the lowest dry biomass, that is, they were the treatments that exhibited the greatest control.

In contrast, the dry biomass recorded for flucarbazone and the combination of mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl was high in the biotypes suspected of having resistance (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Dry biomass of plants from the biotypes of E. crus-galli per experimental unit 30 d after the application of the herbicides inhibitors of ALS and ACCase. Sus = susceptible

The first author's observations about the biological efficacy of ACCase-inhibitor herbicides can be attributed to poorly performed applications when not using the appropriate equipment, particularly the flat fan tips recommended for the application of herbicides. In addition, bad equipment calibration, which can lead to the application of inadequate doses (Salas, 2001).

Presence of resistance

Resistance to mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl

The ED50 in the susceptible biotype was 9.34 g of i.a. of mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl, while the commercial dose is 28 g i.a. ha-1. The V biotype showed an ED50 similar to that of the susceptible biotype, which confirmed that this biotype was susceptible (Table 5).

Table 5 ED50 and resistance index (IR) of the E. crus-galli biotypes collected in the state of Guanajuato for the mixture of the active ingredients mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron-methyl.

| Biotipo | ED50□ | IR |

| Sus | 7.02 | 1.0 |

| I | 8.74 | 1.24 |

| II | 12.63 | 1.79 |

| III | 21.78 | 3.10 |

| IV | 15.59 | 2.21 |

| V | 8.36 | 1.19 |

Sus = susceptible.

For the other biotypes, the resistance indices calculated based on the ED50 obtained from the biomass were greater than one; that is, a greater quantity of active ingredient of this mixture is needed to inhibit 50 % of the growth of these populations with respect to the susceptible biotype.

Results confirm that biotypes III and IV were resistant to mesosulfuron methyl + iodosulfuron methyl; however, biotypes I and II were not considered as resistant populations, according to the indices obtained.

The increase in ED50 is an indicative of initiating weed resistance management programs, since more active ingredient is needed to inhibit 50 % of the growth of these populations.

In addition, one of the causes of resistance is the overdose and repeated use of herbicides with the same mode action, so it is not recommended to apply this mixture of herbicides or other ALS inhibitors for the control of E. crus -galli, and it is suggested to apply the ACCase inhibitor herbicides that in our study showed an efficient control of the species. The success of resistance management depends on a diversified management program that reduces selection pressure on weeds and includes practices such as herbicide rotation, the use of combinations of herbicides with multiple mechanisms of action, crop rotation and the use of other non-chemical control methods.

Resistance to sodium flucarbazone

The results obtained from the dose-response bioassay with the sodium flucarbazone herbicide indicated that no biotype showed any significant degree of resistance to flucarbazone. Biotype II presented a resistance index of 1.35; however, it is not enough to be considered as such. The other biotypes behaved as susceptible when compared with the control biotype (Table 6).

Table 6 ED50 and resistance index (IR) of E. crus-galli biotypes collected in the state of Guanajuato, for the active ingredient sodium flucarbazone.

| Biotipo | ED50 | IR |

| Sus | 202.8 | 1 |

| I | 69.80 | 0.34 |

| II | 275.4 | 1.35 |

| III | 75.43 | 0.37 |

| IV | 146.6 | 0.72 |

| V | 31.50 | 0.15 |

Sus = susceptible.

The factors involved in the development and emergence of resistance are related to weed biology, cultivation, management practices, herbicide residuality, biotype susceptibility, weed population density and its ability to produce seeds, the reservoir and dormancy of susceptible seeds in the soil, the application dose, the number of applications per cycle, the environmental conditions and the action mechanisms of the herbicides. Therefore, poor controls and the risk in the evolution of resistant biotypes are due to the inadequate management of the factors in which it is possible to intervene.

Resistance to ALS inhibiting herbicides, such as mesosulfuron-methyl+iodosulfuron-methyl, is due to the high frequency of mutations (Devine and Preston, 2000) at the action site (Corbett and Tardif, 2006) and the low absorption, transport or metabolic degradation of herbicides (Hatzios, 2001; Osuna et al., 2002) or the overexpression of the ALS enzyme (Yasuor et al., 2009). Therefore, if you want to know the causes of resistance, you must address the aforementioned issues.

Conclusions

The clodinafop propargil and pinoxaden herbicides showed good biological effectiveness on E. crus-galli biotypes from Guanajuato; the herbicides flucarbazone and mesosulfuron methyl+iodosulfuron methyl showed an acceptable effectiveness on the susceptible biotype and low on the biotypes with suspected resistance. In two of the six biotypes studied, we confirmed the E. crus-galli resistance to the herbicide mesosulfuron methyl + iodosulfuron methyl.

Literatura Citada

Burrill, L. C., J. Cárdenas, and E. Locatelli. 1976. Field Manual for Weed Control Research. International Plant Protection Center. Oregon State University. Corvallis, OR, USA. 59 p. [ Links ]

Cerdeira, A. L., and S. O. Duke. 2006. The current status and environmental impacts of glyphosate-resistant crops: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 35: 1633-1658. [ Links ]

Christoffers, M. J. 1999. Genetic aspects of herbicide-resistant weed management. Weed Technol. 13: 647-652. [ Links ]

Corbett, C., and F. Tardif. 2006. Detection of resistance to acetolactate sintase inhibitors in weed with emphasis on DNA-based techniques: A review. Pest Manag. Sci. 62: 584-597. [ Links ]

Cruz V., M., G. Martínez D., R. Cinco C., y L. Avendaño R. 2004. Periodo crítico de competencia de malezas en trigo (Triticum aestivum L.). Agric. Téc. Méx. 30: 223-234. [ Links ]

Délye, C. 2005. Weed resistance to acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase inhibitors: An update. Weed Sci. 53: 728-746. [ Links ]

Devine, M. D. 1997. Mechanisms of resistance to acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase inhibitors: A review. Pestic. Sci. 51: 259-264. [ Links ]

Devine, M. D., and C. Preston. 2000. The molecular basis of herbicide resistance. In: Cobb, A. H., and R. C. Kirkwood (eds). Herbicides and their Mechanisms of Action. Academic Press. Sheffield, Inglaterra. pp: 72-104. [ Links ]

Fischer, A. J. 2013. Resistencia a herbicidas: mecanismos y mitigación. Revista Especial de Malezas. AAPRESID. 29: 3-19. [ Links ]

Gressel, J. 2002. Molecular Biology of Weed Control. Taylor and Francis. London. 504 p. [ Links ]

Hatzios, K. K. 2001. Mechanism of resistance to herbicides. In: De Prado, R., y J. V. Jorrin (eds). Uso de Herbicidas en la Agricultura del Siglo XXI. Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba. Córdoba, España. pp: 275-278. [ Links ]

Heap, I. 2014. Herbicide resistant weeds. In: Pimentel, D., and R. Pashin (eds). Integrated Pest Management. Springer. New York, USA. pp. 281-301. [ Links ]

Heap, I. 2016. International survey of herbicide resistant weeds. http://www.weedscience.com/summary/home.aspx . (Consulta: octubre 2016). [ Links ]

Mallory-Smith, C. A., D. C. Thill, and M. J. Dial. 1990. Identification of sulfonylurea herbicide-resistant prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola). Weed Technol. 4: 163-168. [ Links ]

Osuna, M. D, F. Vidotto, A. J. Fischer, D. E. Bayer, R. De Prado, and A. Ferrero. 2002. Cross-resistance to bispyribac-sodium and bensulfuron-methyl in Echinochloa phyllopogon and Cyperus difformis. Pest Biochem. Physiol. 73: 9-17. [ Links ]

Powles, S. B., and Q. Yu. 2010. Evolution in action: Plants resistant to herbicides. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 61: 317-347. [ Links ]

Ross, M. A., and C. A. Lembi. 2009. Applied Weed Science: Including the Ecology and Management of Invasive Plants. 3rd. ed. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA. 561 p. [ Links ]

Salas, M. 2001. Resistencia a herbicidas, detección en campo y laboratorio. In: De Prado, R., y J. V. Jorrin (eds). Uso de Herbicidas en el Siglo XXI. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba. Córdoba, España. pp. 251-261 [ Links ]

SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera). 2016. Producción Agrícola. Cíclicos 2016. Trigo grano. http://infosiap.siap.gob.mx:8080/agricola_siap_gobmx/AvanceNacionalCultivo.do . (Consulta: julio 2017). [ Links ]

Tafoya R., J. A., y R. M. Carrillo M. 2009. Control de la maleza en el cultivo de cebada en el altiplano. In: Resúmenes del XXX Congreso Mexicano de la Ciencia de la Maleza. 21-23 de octubre. Culiacán, Sin., México. p. 29. [ Links ]

Tafoya R., J. A., A. Ocampo R., y R. M. Carrillo M. 2009. Control de la maleza en el cultivo de trigo en el altiplano. In: Resúmenes del XXX Congreso Mexicano de la Ciencia de la Maleza. 21-23 de octubre. Culiacán, Sin., México. p. 33 [ Links ]

Tranel, P. J., and T. R. Wright. 2002. Resistance of weeds to ALS-inhibiting herbicides: What have we learned? Weed Sci. 50: 700-712. [ Links ]

Valverde, B. E., C. R. Riches, y J. C. Caseley. 2000. Prevención y Manejo de Malezas Resistentes a Herbicidas en Arroz: Experiencias en Centro América con Echinochloa colona. Cámara de Insumos Agropecuarios. San José, Costa Rica. 136 p. [ Links ]

Yasuor, H., M. D. Osuna, A. Ortiz, N. E. Saldain, J. W. Eckert, and A. J. Fischer. 2009. Mechanism of resistance to penoxsulam in late watergrass (Echinochloa phyllopogon (Stapt) Koss.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 57: 3653-3660. [ Links ]

Received: January 2017; Accepted: September 2017

texto en

texto en